News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Oomph library resources: phw 250/250b epidemiologic methods: epidemiologic case study resources.

- Online Books on Epidemiology and Biostatistics

- R for Public Health

- Stata Resources and Tips

- Epidemiologic Case Study Resources

- Rural Health Resources

- Help/Off-Campus Access

Epidemiologic Case Studies

- Epidemiologic Case Studies (US CDC) These case studies are interactive exercises developed to teach epidemiologic principles and practices. They are based on real-life outbreaks and public health problems and were developed in collaboration with the original investigators and experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The case studies require students to apply their epidemiologic knowledge and skills to problems confronted by public health practitioners at the local, state, and national level every day.

- Case Studies (WHO) From "Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations," each case has learning objectives and documentation.

- Case Studies in Social Medicine A series of Perspective articles from the New England Journal of Medicine that highlight the importance of social concepts and social context in clinical medicine. The series uses discussions of real clinical cases to translate theories and methods for understanding social processes into terms that can readily be used in medical education, clinical practice, and health system planning.

- African Case Studies in Public Heath Case study exercises based on real events in African contexts and written by experienced Africa-based public health trainers and practitioners. These case studies represent the most up-to-date and context-appropriate case study exercises for African public health training programs. These exercises are designed to reinforce and instill competencies for addressing health threats in the future leaders of public health in Africa.

- Case Consortium @ Columbia University: Public Health Cases The case collection includes "teaching" cases. Nearly all the cases are multimedia and based on original research; a few are written from secondary sources. All cases are offered free of charge.

- Epi Teams Training: Case Studies From the North Carolina Institute for Public Health, this curriculum includes several interactive case studies designed be used by the Epi Team as a group. These case studies are based on actual outbreaks that have occurred in North Carolina and elsewhere.

- National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science The mission of the NCCSTS at the University at Buffalo is to promote the development and dissemination of materials and practices for case teaching in the sciences. Our website provides access to an award-winning collection of peer-reviewed case studies. We offer a five-day summer workshop and a two-day fall conference to train faculty in the case method of teaching science. In addition, we are actively engaged in educational research to assess the impact of the case method on student learning. "Case Collection" includes over 100 public health cases.

Books of Case Studies

- << Previous: Stata Resources and Tips

- Next: Rural Health Resources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 20, 2024 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/publichealth/PHW250

Welcome To Open Case Studies

Connecting you with real-world public health data.

The Open Case Studies project showcases the possibilities of what can be achieved when working with real-world data.

Housed in a freely accessible GitHub repository, the project’s self-contained and experiential guides demonstrate the data analysis process and the use of various data science methods, tools, and software in the context of messy, real-world data.

These case studies will empower current and future data scientists to leverage real-world data to solve leading public health challenges.

Who Are Open Case Studies For?

Your experiential guide to the power of data analysis.

The Open Case Studies project provides insights about gathering and working with data for students, instructors, and those with experience in data science or statistical methods at nonprofit organizations and public sector agencies.

Each case study in the project focuses on an important public health topic and introduces methods to provide users with the skills and knowledge for greater legibility, reproducibility, rigor, and flexibility in their own data analyses.

Case Study Bank Overview

Real data on ten public health challenges in the U.S.

The following in-depth case studies use real data and focus on five areas of public health that are particularly pressing in the United States.

Vaping Behaviors in American Youth

This case study explores the trends of tobacco product usage among American youths surveyed in the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) from 2015-2019. It demonstrates how to use survey data and code books and provides an introduction to writing functions to wrangle similar but slightly different data repetitively. The case study introduces packages for using survey weighting and survey design to perform an analysis to compare vaping product usage among different groups, and covers how to use a logistic regression to compare groups for a variable that is binary (such as true or false — in this case it was using vaping products or not). This case study also covers how to make visualizations of multiple groups over time with confidence interval error bars.

Opioids in the United States

This case study examines the number of opioid pills (specifically oxycodone and hydrocodone, as they are the top two misused opioids) shipped to pharmacies and practitioners at the county-level around the United States from 2006 to 2014 using data from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). This case study demonstrates how to get data from a source called an application programming interface (API). It explores why and how to normalize data, as well as why and how to potentially stratify or redefine groups. It also shows how to compare two independent groups when the data is not normally distributed using a test called the Wilcoxon rank sum test (also called the Mann Whitney U test) and how to add confidence intervals to plots (using a method called bootstrapping).

Disparities in Youth Disconnection

This case study focuses on rates of youth (people between 16-24) disconnection (those who are neither working nor in school) among different racial, ethnic and gender subgroups to identify subgroups that may be particularly vulnerable. It demonstrates that deeper inspection of subgroups yields some differences that are not otherwise discernable, how to import data from a PDF using screenshots of sections of the PDF, and how to use the Mann-Kendall trend test to test for the presence of a consistent direction in the relationship of disconnection rates with time. This case study also shows how to make a visualization that stylistically matches that of an existing report, how to add images to plots, and how to create effective bar plots for multiple comparisons across several groups.

Mental Health of American Youth

This case study investigates how the rate of self-reported symptoms of major depressive episodes (MDE) has changed over time among American youth (age 12-17) from 2004-2018. It describes the impact of self-reporting bias in surveys, how to get data directly from a website, as well as how to compare changes in the frequency of a variable between two groups using a chi-squared test to determine if two variables are independent (in this case if the sex of the students influenced the frequency of reported MDE symptoms in 2004 and 2018). This case study also demonstrates how to create direct labels on visualizations with many groups across time, as well as how to create an animated gif.

Exploring CO2 Emissions Across Time

This case study investigates how CO2 emissions have changed since the 1700s and how the level of emissions has compared for different countries around the world. It explores how yearly average temperature and the number of natural disasters in the United States has changed over time and provides an introduction for examining if two sets of data are correlated with one another. This case study also goes into great detail about how to make what are called heatmaps and other plots to visualize multiple groups over time. This includes adding labels directly to lines on plots with multiple lines.

Predicting Annual Air Pollution

This case study uses machine learning methods to predict annual air pollution levels spatially within the United States based on data about population density, urbanization, road density, as well as satellite pollution data and chemical modeling data among other predictors. Machine learning methods are used to predict air pollution levels when traditional monitoring systems are not available in a particular area or when there is not enough spatial granularity with current monitoring systems. The case study also demonstrates how to visualize data using maps.

Exploring Global Patterns of Obesity Across Rural and Urban Regions

This case study compares average Body Mass Index measurements for males and females from rural and urban regions from over 200 countries around the world, with a particular emphasis on the United States. It provides a thorough introduction to wrangling data from a PDF, how to compare two paired groups using the t test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test using R programming, and how to make visualizations of group comparisons that emphasize a particular subset of the data.

Exploring Global Patterns of Dietary Behaviors Associated with Health Risk

This case study investigates the consumption of dietary factors associated with health risk among males and females from over 200 countries around the world, with a particular emphasis on the United States. It demonstrates how to wrangle data from a PDF; how to combine data from two different sources; how to compare two paired groups and multiple paired groups using t-tests, ANOVA, and linear regression; and how to create visualizations of several groups and how to combine plots together with very different scales.

Influence of Multicollinearity on Measured Impact of Right-To-Carry Gun Laws

This case study focuses on two well-known studies that evaluated the influence of right-to-carry gun laws on violent crime rates. It demonstrates a phenomenon called multicollinearity, where explanatory variables that can predict one another can lead to aberrant and unstable findings; how to make visualizations with labels, such as arrows or equations; and how to combine multiple plots together.

School Shootings in the United States

This case study illustrates ways to communicate trends in a dataset about the number and characteristics of school shooting events for students in grades K-12 in the United States since 1970. It demonstrates how to create a dashboard, which is a website that shows patterns in a dataset in a concise manner; how to import data from a Google Sheets document; how to create interactive tables and maps; and how to properly calculate percentages for data when there are missing values.

Which Case Study Is Right For Me?

Connecting with the public health data you need.

The Open Case Studies project approaches data in many different ways. The guide below will help connect you with a case study:

Data science projects often start with a question. Here, you may look for case studies that explore a question that is similar to one you are interested in investigating with your data.

How does something change over time?

Investigating how a variable has changed over time can help identify consistent trends.

How do survey responses compare for different groups over time?

Survey data requires special care and attention to the survey design.

How do groups compare?

Public health researchers are often interested to know if one group is more vulnerable than another or if two or more groups are actually different from one another.

How do groups compare over time?

Comparing several groups over time can provide insight into if the change over time is different for different groups.

How do paired groups compare?

Paired groups are those that are not independent in some way. Perhaps you want to know how data from the same person over time compares with that of another person over time, or perhaps you are interested in how something changed in a city before and after an intervention, or perhaps you want to compare groups using data that has structure where there is coupling or matching of data values across samples.

Are certain groups or possibly subgroups more vulnerable?

Understand how to compare subpopulations at a deeper level.

How does something compare across regions?

Often it is useful to investigate if data differs by region, as many environmental, cultural, and political differences can influence public health outcomes.

How can I predict outcomes for new data?

Learn how the data might look next year or for locations that you don’t have data about.

Does this influence my data?

Analyze how a variable influences another variable.

Are these two variables related to one another?

Understand how two variables are related and how strongly they are related to one another.

How can I display this data for others to find and interpret and use easily?

Make it easy for others to find your data, see the major trends in your data, or search for specific values in your data.

Data can come from many different sources, from the more obvious like an excel file to the less obvious like an image or a website. These case studies demonstrate how to use data from a variety of possible sources.

Using data from a PDF or just parts of a PDF can be challenging. You could type the data into a new excel file, but this can result in mistakes and it is difficult to reproduce.

Data are often in CSV files and it is typically easy to import data and work with data in this form. However, sometimes it can be difficult if, for example, the first few lines are structured differently or if you have unusual missing value indicators.

If you find data on a website that doesn’t allow you to download in a convenient way, you can actually directly import the data into R programming language.

This is one of the most common data forms, and it is typically easy to import data and work with data in this form. However, sometimes it can be challenging, especially if you have many files.

You can extract text from image files. This can be useful if, for example, you want to only use certain parts of a PDF.

It is possible to find the data that you need to use from an application programming interface (API).

Google Sheet

You can download data from a Google Sheet, copy and paste it into Excel, or directly import the data into R programming language.

Survey data/Code books

Working with survey data requires special care and attention, and you can do this directly with R programming language.

Multiple files

If you find that you need to import data from multiple files, there is a more efficient way to do so without importing each one by one.

Data wrangling is the process of organizing your data in a more useful format. These case studies explore how to clean, rearrange, reshape, modify, filter, combine, or join your data.

Extracting data from a PDF

Extracting and organizing data from a PDF will make it easier to use.

Geocoding data

The process of assigning relevant latitude and longitude coordinates to data values is called geocoding. This can be helpful (although not always necessary) to create a map of your data.

Recoding data

If you have data values that are confusing and could be changed to something better, or if you want to convert your data to true or false, you might want to consider recoding these values.

Methods of joining data

Sometimes, you obtain data from multiple sources that need to be combined together.

Filtering data

Perhaps you need to filter your data for only specific values for given variables. In other words, you might want to filter census employment data to only values for females who are also Black and live in Connecticut.

Modifying data (normalizing, transforming, scaling etc.)

Sometimes it is difficult to know when or how to normalize data.

Working with text

You can work with, remove, replace, or change words, phrases, letters, numbers, or punctuation marks in your data.

Reshaping data

Sometimes it is useful to shape your data so that you have many columns (for example, when performing certain analyses), however it can be useful at other times (for example, when creating plots) to collapse multiple columns into fewer columns with more rows.

Repetitive process

Sometimes you need to wrangle multiple datasets from different sources in a similar manner.

A picture is worth a thousand words, particularly when it comes to interpreting data. These case studies demonstrate how to make effective visualizations in various contexts. The first ten represent basic visualizations while 11-22 are more advanced.

A table that is easy to interpret

Adding colors or simple graphics can make tables easier to interpret.

Scatter plot

Scatter plots can be a strong option for evaluating the relationship between variables, and especially for evaluating changes in a variable over time.

Line plots are often useful for evaluating changes over time.

Bar plots are a good choice if you want to compare data to a threshold.

Box plots are particularly useful for comparing groups with many data values. They provide information about the spread of the data.

Pie chart/waffle plot

Pie charts or waffle plots can be a strong option when comparing relative percentages.

It can be difficult to visualize multiple groups at simultaneously. In these situations, heat maps can be a great option.

Correlation plots

If you have many variables and need to know if they are correlated to one another, there are methods to efficiently check this.

Visualize missing data

It can be helpful to quickly identify how much of your data is missing (has NA values).

Create a map of your data

Often the best way to interpret regional differences in data is to make a map.

- Advanced Visualizations

Matching a style

If you are working with collaborators, you can make your visualizations match the style of their figures.

Faceted plots allow you to quickly create multiple plots at once

It can be difficult to visualize multiple groups at the same time, so faceted plots are a great option in this situation.

Adding labels directly to plots with many different groups

If you compare many groups over time, for example, it can be difficult to see which line corresponds to which group. Adding labels directly to these lines can be very helpful and negates the need for an overcomplicated legend.

Emphasize a particular group

Sometimes you will have several different groups and you want to highlight a specific group.

Adding annotations to plots

Adding labels, such as thresholds, arrows, or equations, can make it easier for people to interpret your plot.

Add error bars to your plot

Adding error bars can help convey information about the confidence of the estimates in your plots.

Combine multiple plots together

Sometimes it is useful to put a variety of plots together and add text to explain what the plot shows.

Create an interactive plot when you have too many groups to label

If you compare a very large number of groups, it can be difficult to tell what is happening. Often it can help to make the plot interactive so that the user can hover over points or lines to see what they indicate.

Create an interactive map of your data

Sometimes it is easiest to see regional differences by interacting with and exploring an interactive map.

Create an interactive table of your data

Sometimes you might want to be able to search through your data or allow others to easily do so.

Add images to your figures

Including images to a plot, such as a logo, can be a helpful addition.

Create an interactive dashboard/website for your data

Dashboards can quickly convey major trends in a dataset, and they can also allow users to interact with the data to choose what aspects about the data they wish to explore.

To better understand data, it is helpful to use statistical tests. These case studies demonstrate a variety of statistical tests and concepts.

Are two groups different?

Correlation

Are two variables related to one another?

Are multiple groups different?

Linear regression

Would you like to compare groups?

Chi-squared test of independence

Do the frequencies of two groups suggest that they are independent?

Mann-Kendall Trend test

Is there a consistent change over time?

Machine learning

Would you like to predict data?

Calculate percentages with missing data?

Would you like to calculate percentages, but you are missing some data?

About The Project

Learn about the team behind the Open Case Studies project.

As part of the larger Open Case Studies project (OCS) at opencasestudies.org , these case studies were developed for and funded by the Bloomberg American Health Initiative. The OCS project is made up of a team of researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH).

Let us know how the Open Case Studies project has enhanced your educational curriculum or ability to tackle tough data-rich research projects.

JHSPH Faculty Contributors

Jessica Fanzo, PhD

Brendan Saloner, PhD

Megan Latshaw, PhD, MHS

Renee M. Johnson, PhD, MPH

Daniel Webster, ScD, MPH

Elizabeth Stuart, PhD

Bloomberg American Health Initiative

Joshua M. Sharfstein, MD – Director, Bloomberg American Health Initiative

Michelle Spencer, MS – Associate Director, Bloomberg American Health Initiative

Paulani Mui, MPH – Special Projects Officer, Bloomberg American Health Initiative

Other Contributors

Aboozar Hadavand, PhD, MA, MS, Minerva University

Roger Peng, PhD, MS, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Kirsten Koehler, PhD, MS, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Alex McCourt, PhD, JD, MPH, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Ashkan Afshin, MD, ScD, MPH, MSc, University of Washington and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)

Erin Mullany, BA, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)

External Review Panel

Leslie Myint, PhD, Macalester College

Shannon E. Ellis, PhD, University of California – San Diego

Christina Knudson, PhD, University of St. Thomas

Michael Love, PhD, University of North Carolina

Nicholas Horton, ScD, Amherst College

Mine Çetinkaya-Rundel, PhD, University of Edinburgh, Duke University, RStudio

Let Us Know How You're Using Open Case Studies

As the Open Case Studies project expands, we learn from you. Tell us what data you'd like to see, how you're using the data, or anything we can do to improve the project.

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Designing an interactive field epidemiology case study training for public health practitioners.

- RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC, United States

Globally, public health practitioners are called upon to respond quickly and capably to mitigate a variety of immediate and incipient threats to the health of their communities, which often requires additional training in new or updated methodologies or epidemiologic phenomena. Competing public health priorities and limited training resources can present challenges in developed and developing countries alike. Training provided to front-line public health workers by ministries of health, donors and/or partner organizations should be delivered in a way that is effective, adaptable to local conditions and culture, and should be an experience perceived as a job benefit. In this review, we share methods for interactive case-study training methodologies, including the use of problem-based scenarios, role-play activities, and other small-group focused efforts that encourage the learner to discuss and synthesize the concepts taught. We have fine-tuned these methods through years of carrying out training of all levels of public health practitioners in dozens of countries worldwide.

Background and Rationale

In a rapidly changing field marked by frequent turnover, the need to provide continuing education for public health practitioners is constant. Often there is no requirement for prior credentialing in public health for local-level jobs 1 , 2 . Alternatively, training and professional development may be clinically-oriented as opposed to the more relevant population based public health focus ( 1 ). In many parts of the world public health training programs targeting the health professions are minimal ( 2 ). For these reasons, in the US and elsewhere, public health professions tend to be high-responsibility, low-pay jobs, marked by high turnover rates ( 3 ).

In many low- and middle-income countries, keeping educated health professionals in-country is challenging ( 4 ). Public health professionals are discouraged by lack of proper compensation and insufficient opportunities for continuing professional development and education ( 5 ). Results from a 2006 study conducted for the Ugandan Ministry of Health investigating health workforce morale, satisfaction, motivation, and intent to remain in Uganda showed that health workers were dissatisfied with their jobs. About one in four noted a desire to leave the country to improve their outlook ( 6 ). Further complicating matters, those who have learned occupational skills through on-the-job experience are vulnerable to being laid off with changes of government administration ( 7 ).

Our experience carrying out training activities over the last two decades has provided the opportunity to train public health practitioners in-person, online, and via self-directed learning. We have designed and conducted trainings for front-line local responders as well as district and national-level officials both in the US and abroad. For example, in the US, we have trained county and state-level public health workers in surveillance and outbreak investigation through in-person training courses, Web conferencing platforms, and via both synchronous and asynchronous distance-based methods. We have trained national-level officials and laboratorians through specialized in-person trainings as well as via large conference-based and train-the-trainer style settings. Examples include organizing and developing content for a multi-agency tabletop exercise focused on bioterrorism response post-9/11, development of a curriculum focused on rapid response to avian and pandemic influenza, strengthening workforce capacity in sentinel site surveillance for respiratory illness, and, with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a full Master's-degree level curricula the Central American Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) Master's degree program, as well as front-line public health practitioner trainings at Intermediate and Basic-levels within Central America and topic-specific FETP modules elsewhere. These efforts were supported by CDC, the National Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), and others.

Whether delivered to a non-epidemiologist who finds themselves responsible for outbreak investigation, or to a national epidemiology official who will subsequently oversee training of their staff, the case study or interactive exercise typically serves as a pivotal feature of training for public health professionals, moving them toward actively engaging in learning, knowledge sharing and in the application of previously learned information ( 8 ). We describe key elements in the development and use of case studies as a learning tool for public health practitioners, based on our years of experience in developing, implementing, and evaluating public health trainings. The learning objectives of this article are the following:

• Identify critical teaching points around which to structure a case study training.

• Consider relevant sources of information to provide information and “plot” to a case study.

• Choose a case study format appropriate for the trainees and content.

• Incorporate design elements that encourage interaction and thoughtful discussion among learners into a case study.

Pedagogical Framework

Case-study based learning approaches have proven particularly effective in the medical education context. Comparison studies conducted in the medical sciences have found interactive, case-study focused learning a more effective teaching tool than didactic lectures ( 9 , 10 ). Although the literature focuses on medical education, the success of case studies in public health education is also reflected in the growing number of public health programs with problem-based curricula ( 11 , 12 ). Our goal has been to create effective training materials for public health professionals that present relevant, interactive, and interesting content that teach job skills (not merely general principles) in a way that can be quickly understood and applied while providing an opportunity for peers of different experience levels to learn from one another.

Curriculum development is a multi-layered process involving instructional designers, subject matter experts, and editorial and art personnel ( 13 ). Training format is highly dependent upon the needs of the involved partner(s). Information-driven training presented in the didactic style only can be less effective for information retention and learner motivation. Learning methods allowing the participant to contribute meaningfully from their own experience, develop skills in a supervised setting, and practice skills immediately pursuant to learning them, will result in more retention and ability to apply the skills taught. Learners who are given ample opportunities to analyze past experience through reflection, evaluation and reconstruction fulfill a key element of experience-based learning and are able to draw deeper meaning from prior events in their personal and professional lives ( 14 ). As such, interactive and problem-based approaches to building applied public health skills are critical features of many public health trainings. Interactive and problem-based approaches engender openness toward new experiences, a critical element in facilitating lifelong learning. At the social or group level, these approaches help emphasize critical social action and the importance of adopting a stance shaped by moral and socio-political responsibility ( 14 ).

Dissemination of information or didactic methods may be used as a means of communicating concepts, methods, or the use of new technologies, but should be accompanied by interactive teaching methods. Interactive teaching can occur in a variety of settings, which may be dependent on program, resources, and learner characteristics. The training audience is professional public health practitioners, who may or may not be formally educated in public health.

The size of the training has varied vastly, from fewer than 12 learners to over 100. With larger groups, we often have a lead instructor who is experienced both in the subject area and in carrying out trainings who is accompanied by “facilitators” or small-group leaders who can provide guidance during case-study work in break-out sessions.

Although we have designed trainings in many different formats, the most successful setting for a case study in our experience has been one where learners come together in-person for a scheduled period of instruction and worked activities, ranging in time from half-day trainings to 2-week courses.

The success of a particular training methodology is difficult to assess. For the several dozen trainings we have carried out, we include a participant evaluation that captures information such as whether the participant found the training useful, whether they feel able to use the information learned in their job, how satisfied they were with the training, and open comments. Informal interaction with trainees and feedback from these surveys over the years has shaped the case study format presented here. The success of a public health training should be measurable by participants' ability to perform specific job functions, and more broadly, improvements in components of the public health system such as timeliness and completeness of communicable disease reporting and surveillance.

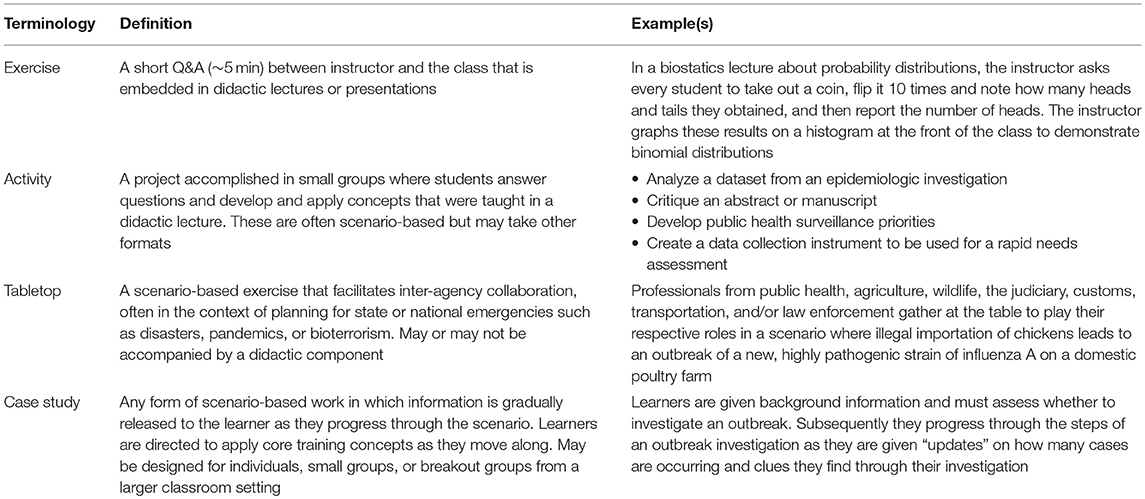

Blueprints for an Interactive Curriculum

There are several considerations when planning and developing curriculum materials. First, the needs of the intended target audience (i.e., the learners) should form the core of any development process. The curriculum should be designed to both meet training and skill-building needs, and to approach the target audience in a comfortable and accessible way; it should meet them at their current level; the materials should address the fact that—trained or not—professionals who have been working in any field have experience to contribute that adds to the depth of a training. Second, training materials should be developed in a way that ensures consistency in the delivery. Thus, lectures should include a speaker script and built-in questions for the audience with suggestions to both engage learners and continually check knowledge acquisition. Having the script provides particular flexibility for train-the-trainer programs or other circumstances where the person with the most content and training expertise may not be the one to personally deliver the content to all trainees. Case studies should be developed in a standard format that includes an instructor guide complete with suggested answers, worked calculations, and suggested instructional methods for emphasizing critical teaching points. These methods ensure that critical content is taught regardless of the depth of experience of the teacher or facilitator. Finally, training materials should engage the learner in discussion and healthy debate, contribute to their own learning, and provide peer-to-peer learning opportunities. We discuss several types of interactive exercises which are often collectively referred to as “case studies,” but specifically may feature different elements (Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Terminology, definition, and examples of interactive training activities often referred to as “case studies.”

We propose the following general objectives of a group case study, regardless of format or topic area:

• To meet defined learning objectives or competencies.

• To learn in an environment that respects the skills and abilities of the learners, and allows each learner to use and apply their unique skills.

• To have learners interact with each other, thus enhancing their own learning through listening to the ideas and experience of fellow learners.

• To exhibit genuine interest in and be motivated by the content they are learning.

We have found that there are four critical conceptual elements in developing and executing an interactive training:

1. Reference key points or concepts to be learned and applied.

2. Guide learners to work through a problem.

3. Keep learners engaged through active questioning.

4. Draw on learners' experience.

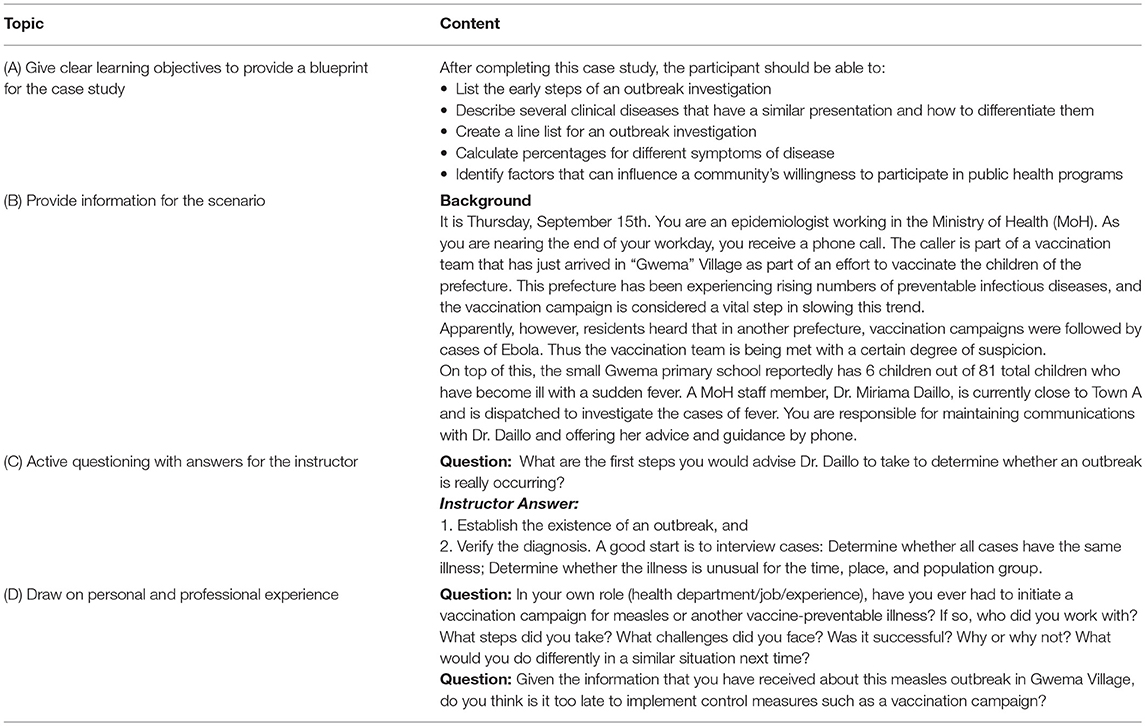

Each of these is described in detail below, with a measles outbreak in a small African village used as a guide for demonstrating their implementation through a case study exercise.

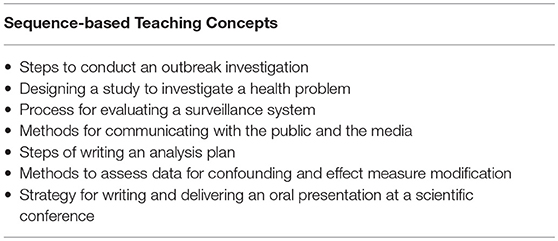

Reference Key Points or Concepts to Be Learned and Applied

The main intent of a case study is to teach predefined content. Often training delivery of a case study is preceded by didactic content, or other information-driven training such as web-based tutorials, workbooks, or reading material. Whether or not information-driven training is included, the key concepts to be learned and applied should be viewed as the framework upon which the rest of the case study will be built. For example, a lecture or reading may put forth a set of 9 steps to investigate an outbreak. The case study format will then be dictated by achieving each of these 9 steps. It is of benefit to clearly and obviously delineate any key steps or phases as one works through the case study. The beginning learner gains more benefit from understanding a firm case study structure than from trying to figure out which step or concept should be applied in which situations, even though events may not occur so neatly on the job. When teaching a set of concepts, it is better to teach them clearly and simply than to allow the learner to become frustrated, struggle, and possibly fumble. More advanced learners can be given the opportunity to struggle with decision-making and unexpected sequences of events, after they have mastered a clear set of tools from which to draw. A few examples of clearly structured concepts that lend themselves to case studies are given in Table 2 , and a scenario using these types of structures within a case study is given in Table 3 .

Table 2 . Examples of concepts that can be given a clear sequence or structure for teaching purposes.

Table 3 . Scenario-based examples of a measles outbreak in a small village case study.

Regardless of topic, a simple introduction for the participant and the instructor as to the point and process of the case study is required. Begin by providing learning objectives (as in Table 3A ) and a short introduction to the case study, including if, and how, learners should interact with others, the resources they should use for case study completion, the product that is expected, and the estimated time required to complete the tasks given.

Guide Learners to Work Through a Problem

A hallmark feature of a case study is working through a problem that parallels or is based on a real-life situation. An appealing format is to present the learner with introductory or background information and update information as the learner works through the problems of the case study.

Basing information and scenarios on real events is the best way to prevent the scenario from feeling contrived. Possible sources of information for scenarios include the experience, internal reports, or data of the curriculum developer or colleagues; published literature; local, national, or international bulletins; health situation updates provided by State health departments, CDC or WHO; and less formal sources such as news reports and ProMed, the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases. In some cases, the details of an actual outbreak, surveillance system, or other event can be used directly. Typically, an actual scenario can be used, but the details can be embellished, drawn out, or supplemented by different events in order to meet the learning purposes of the case study. For example, in a scenario where the learner is in the role of someone getting ready to plan a case-control study, the setting from a ProMed report or international bulletin might be ideal, but the details given from a case-control study published in the literature provide the topical details needed to expand upon the case study scenario. Unless teaching about a specific real-event is a learning objective, a case study developer should be free to modify details and provide creative license to developing characters for the case study events. The example case study used in Table 3 of this article was inspired by a health news article about difficulties facing vaccination campaigns in Guinea 3 , and was structured on WHO recommendations for measles surveillance and case definitions ( 15 ). Resource material used to develop the case study should be appropriately cited.

Once the learning objectives, introduction, and plot for the scenario are outlined, the learner or the group is positioned within the scenario through assignment of specific roles or responsibilities, for example:

• “You are the health director for Mlima Province, and you receive a phone call from the local hospital epidemiologist who is concerned about….”

• “You are a surveillance officer with the Forêt Health district, and you have just been placed in charge of developing a new surveillance system for…”

The plot of the case study can then be developed as questions are posed, the learner makes plans, decisions, calculations, and more. An example presentation of the scenario based on the previously established measles scenario is given in Table 3B .

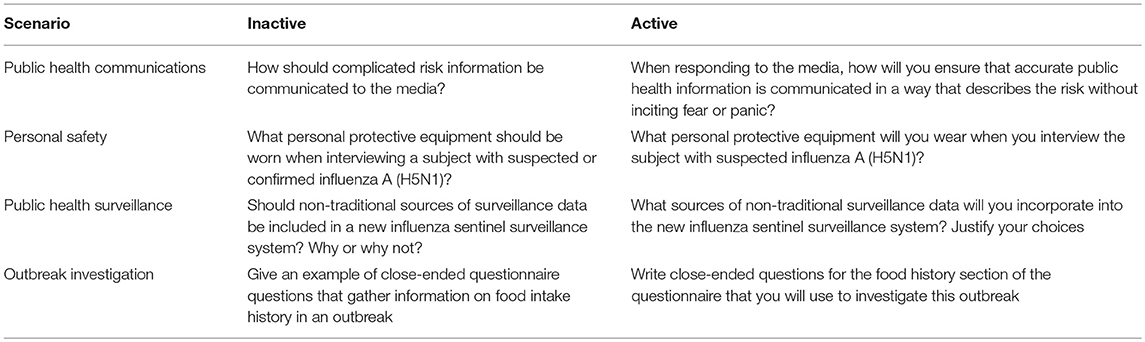

Keep Learners Engaged Through Active Questioning

A key to a successful case study is placing learners in an active role, rather than asking them to reproduce information-driven training concepts in the context of the scenario. Although a case study is designed to be a classroom tool, in field epidemiology the case study should strive to put the learner in the field. For data-centered trainings, this can be accomplished by instructing the learner to carry out data processing and analysis. For example, a learner may be provided with a line listing and asked to construct an epidemic curve, or they may be provided a two-by-two table and asked to calculate relative risk. The effort to place the learner in an active role is particularly important for more routine types of questions that aim to get the learner to repeat concepts (as with an information-driven training). Some examples of inactive questions and how they can be modified to be active are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4 . Comparison of scenarios with inactive vs. active questioning methods.

Questions should cause the learner to use the knowledge and information they have gleaned both within and outside of the training to “act” or make a decision but should not affect the ultimate plot of the case study. See an example from the measles case study in Table 3C .

Draw on Learners' Experience

Adult learners are motivated by experiences that affect them personally. Facilitating contributory participation increases their personal investment ( 16 ). For a group case study, there are multiple advantages in using the case study to draw out learners' experience and personal perspective. First, when learners contribute their own experience to the case study, they gain confidence and enjoyment throughout the activity. Second, a case study that assumes learners have no experience or contribution may feel pedantic or even condescending. Third, encouraging the learner to share their ideas, opinions, and experience creates a synergistic learning opportunity that the questions on the page alone cannot accomplish. This can be done by asking discussion or reflection questions during the progress of the exercise and at its conclusion. Questions that aim to solicit information from the learner regarding past experiences he or she has in making decisions or navigating situations like those encountered in the case study can be effective in enhancing the learning experience. These types of questions can also encourage beneficial self-reflection and allow for recognition of how skills have been or could be applied in reality. Alternatively, questions that treat issues or controversies with no perfect answer fit into the context of the case study while drawing on learners' opinions, often leading to rich dialogue and experience sharing. Table 3D provides a scenario-based example of how to draw upon learner experiences relevant to the measles case study.

Interactive Training Design Options

The specific design used will depend on training content, setting, and the number of learners. Below, we discuss several designs in the context of smaller groups (e.g., 9 or fewer individuals) as well as larger groups (e.g., 10–30 individuals). In many cases, larger groups can be accommodated with small-group case study designs. Using “breakout” groups, where a classroom of a couple dozen or more breaks into smaller groups for case study work, is the easiest method to conduct participatory case-study based training. In many cases, small modifications can be made that also take advantage of the larger class size.

Problem-Based Scenarios

Problem-based scenarios are the mainstay of case study trainings. They guide learners through carrying out activities and can be flexible in length, depending on the depth of information covered and activities or computations required.

Small Groups

In a problem-based scenario, a situation or background information is presented, and the individual or small group must work through a series of questions that address learning objectives in the context presented. Questions ask learners to provide information, conduct a calculation, or come to a decision and move on to the next question. Additional information that adds to the scenario may be provided once or several times throughout the case study.

Large Groups

A couple variations on the problem-based case study scenario make them more interesting in the large group setting. One option is to create slightly different scenarios for breakout groups. For example, in a case study where groups are designing surveillance systems according to set principles taught in class, each small group can focus on a different set of diseases or conditions for their surveillance system. Alternatively, small groups can be provided with updates unique to their group. While this requires additional work in developing case study answer guides, small groups can present their results to each other at the end of the session and can learn more about public health challenges and considerations than just the work they themselves have performed.

Role plays are excellent tools for practicing scenarios in which the learner must think of what to say or do, and work well for interview situations and meeting scenarios. They are best used among learners who have already spent some time together, so that fewer inhibitions exist.

While many case studies ask the learner to assume they have a specific role or identity in order to answer case study questions, a role-play asks a group of learners to go a step further by carrying out interactions with other group members from the perspective of the role they are playing. To prevent learners from feeling uncomfortable in carrying out their role play, each “role” should contain specific guidance with information about their character, including general terms about what they should say and do in the role play.

Acting out an interview can provide inexperienced learners an opportunity to practice and offers experienced learners an opportunity to add improvisational content from their own experience. Scenarios may have learners conduct interviews with food workers, business proprietors, case-patients, research subjects, hospital personnel, and more. Additionally, they may be the interviewee with members of the media or government officials. Both the person conducting the interview and the person being interviewed are given guidance that can include questionnaires or question topic domains for the interviewer, a personality profile of their roles, background information for the person answering questions, top priority concerns for stakeholders, and any other details relevant to the situation. Additionally, role players can be given guidance to cause challenges for each other. For example, an interviewee's information sheet can tell them that they do not like to discuss “personal” problems, and they should do their best to avoid directly answering questions that ask for sensitive information.

Town hall meetings, stakeholder meetings, or media events can be simulated when roles relevant to the situation are assigned to different group members. For example, group members could be in a scenario dealing with student health, and members can be assigned the roles of school officials, parents, health department personnel, or students. Information sheets for each role can encourage the role player to be at odds with others to encourage discussion, bring up concepts taught in the class, and rationalize their actions relevant to the scenario. The value derived from role playing is in practicing personal interactions and the process of considering various viewpoints.

Role plays can be carried out within the context of the large group by dividing the audience into breakout groups, each representing a group of people, such as health spokespeople, media, or community members. The entire group would have the same pre-defined list of character traits or concerns, but individuals within the group voicing their own perspective provide lively interaction. Another option is to have each small group carry out the same role play, with one person per role, and then to follow the role play with a large group discussion. The instructor can ask questions such as, “For those of you who conducted the interview, what was the most challenging aspect of obtaining the information you needed?” Debriefing encourages learners to process what they have learned and allows them to share their own experiences in similar circumstances.

Create a Common Product

This exercise is particularly useful when the skills to complete a large task are being taught, such as skills for writing reports or designing surveillance systems.

Although it is not feasible, in a classroom setting, to have learners complete a large task at their desk, as a group they can efficiently combine forces to cover key concepts from the teaching and produce a common paper, outline, graph, or presentation that addresses key points. Simple example assignments to a small group include:

• Given the scenario, create a flow diagram of a surveillance system that collects population-based pneumonia and influenza data.

• Write the outline of a bulletin article that summarizes the outbreak investigation methods and results that we have worked through today.

• With each group member taking responsibility for one section of a protocol, write an outline for key content to be included in each section. Then share your results with your group members and solicit their feedback.

Breakout groups creating a common product can provide an added dimension and present their product to the entire class. In these cases, it is beneficial to ask the class for constructive criticism on each other's work. Audience members can rate the presenting group against how well they addressed class concepts or met defined criteria. We have used Olympic-style score cards for this task, which lessens the risk of “speaking out” from the viewpoint of the learner offering feedback, but also gives the instructor impetus to ask specific individuals for their rationale in providing that score.

“Go Out” Assignments

Although the ability to use this exercise is highly dependent upon the training setting, “going out” is an interactive way to solidify concepts in questionnaire design, questionnaire execution, and data collection.

Small or Large Groups

If a training is being held in a location where learners have easy and safe access to a public lunch room, university students, or a busy walkway or plaza, the learner can go out of the classroom and engage the general public in practicing basic interviewing skills and piloting questions from a data collection instrument. For example, the learner can collect data to bring back to the classroom, such as whether people are wearing hats, so they can create a collective distribution diagram during a biostatistics lesson. A specific and somewhat tight time limit should be given with the understanding that this is a part of the training, not a break.

Presentations From the Field

Where instruction is being given to individuals representing a variety of expertise levels, presentations by two or three learners who have more experience or expertise can provide a highly educational perspective. For example, in a training we carried out on strengthening population-based influenza surveillance, influenza officers from countries with a strong surveillance system were asked ahead of time to present on the design, site selection, case selection, and limitations or barriers in their surveillance systems. Other learners, on hearing the presentations, asked specific logistical and operational questions and observed how concepts being taught in a lecture really did apply to the “real world.” This helps build professional networks that learners can turn to for expertise or advice post-training.

Much like the practice of field epidemiology itself, there is an art and a science to producing a case study. We lay out a process for structuring a case study around key teaching points, finding elements to include in a case study plot, and incorporating interactive activities and methods throughout a case study, acknowledging that real-world situations may not always follow a predefined sequence.

First, ensure that the goals and content of the training are compatible with the goals of a case study mentioned earlier in this paper. Case studies lend themselves well to situations in which the learners have some experience working in their designated fields to enhance their participation. Clear didactic materials (whether lecture, job aid, or other format) for learners to refer to can keep the discussion focused appropriately. When a group of learners comes together, the discussion can flounder or become derailed by lack of clarity in the underlying concepts. Thus, it is important that any didactic materials also be carefully crafted. An invited or guest speaker for didactic materials can be beneficial but can also confuse learners if concepts are presented differently than in the case study or other training materials. If guest speakers are delivering didactic content, we have found that it is easiest to provide them slides covering the critical points. This ensures the speaker meets the required objectives, and provides a benefit to the course as the speaker can give subject matter feedback to curriculum developers. When teaching complex or involved ideas, we have found that having an additional checklist or conceptual aid handy helps keep the discussion on track (and the training on time).

Second, consider the amount of time for the training, characteristics of the learners and training content, and select a format. For long trainings, change the case study format to prevent learner fatigue. However, do think about contextual factors when selecting a format. In one multi-day training we carried out, learners were to complete a “go-out” assignment. However, this assignment was near the end of the week (learners were tired), and we chose an hour just before lunch to complete the assignment so that students would be able to interact with a larger number of patrons at the cafeteria at the training site. However, most of our learners were distracted by a coffee and a snack. While they eventually completed the assignment, we lost almost an hour of training time. Other considerations for choosing a format include number of participants, level of learner expertise, cultural sensibilities in interacting with one another, and availability of teaching and support staff.

Third, identify key steps and teaching points for inclusion as questions or processes during the case study. If the training content is not easily related to a set of steps or a process, it should be tailored to the identified learning objectives and should ensure that the “action” verbs from learning objectives are carried out. Write questions around these points that coincide with the plot or unfolding of the scenario. Professional experience or published literature can provide a basis for scenario development.

Fourth, ensure that questions are clear and action-oriented. Always provide an answer key or main teaching points that should be derived from each question in an instructor copy. Estimate that it will take about 10 min for a group to read, discuss, and record answers to each question.

In settings where breakout groups are utilized, it is recommended there be a facilitator embedded with each group to help moderate, ensure all have a chance to participate, that appropriate effort is being exerted, and that learners generally arrive at the intended answers.

Participatory case studies are a beneficial way of delivering training for professionals who need to learn, reinforce, and apply specific skills to carry out their job duties. In the field of Public Health, where the responsibilities and hours can be significant, the challenge of recruiting and maintaining dedicated workers must be met in order to protect and promote healthy communities. Training public health professionals to learn new skills and encouraging them to share their experience with others through a network-building group case study is an opportunity that is valuable for our public health work force as well as for our communities.

Author Contributions

AN wrote the manuscript with significant contribution from LB. PM conceptualized the manuscript. All authors provided content expertise, contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

This publication was supported, in part, by the Cooperative Agreement Number 1U19GH001591 funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the insight and feedback from partners and trainees over the past two decades.

1. ^ Fairfax County Virginia: Public Health Nursing at the Fairfax County Health Department. http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/hd/careers-in-public-health/public-nursing-jobs.htm (2016) (Accessed July 11, 2016).

2. ^ Summit County Public Health: Careers in Public Health. Careers in Public Health. http://scphoh.org/pages/careers.html (2015) (Accessed July 11, 2016).

3. ^ IRINNews.org Human Rights: Vaccination teams defeat “Ebola effect” in Guinea (2015). http://www.irinnews.org/news/2015/04/29 (Accessed August 13, 2018).

1. Anyangwe SCE, Mtonga C. Inequities in the global health workforce: the greatest impediment to health in sub-saharan Africa. Int J Env Res Pub Health (2007) 4:93–100. doi: 10.3390/ijerph2007040002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. The World Health Report 2006 - Working Together for Health. WHO (2006). Available online at: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ (Accessed September 29, 2015).

3. Pourshaban D, Basurto-Dávila R, Shih M. Building and sustaining strong public health agencies. J Pub Health Manag Pract. (2015) 21 (Suppl. 6):80–90. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000311

4. Mackey TK, Liang BA. Rebalancing brain drain: exploring resource allocation to address health worker migration and promote global health. Health Policy (2012) 107:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.006

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Cancedda C, Farmer PE, Kerry V, Nuthulaganti T, Scott KW, Goosby E, et al. Maximizing the impact of training initiatives for health professionals in low-income countries: frameworks, challenges, and best practices. PLoS Med. (2015) 12:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001840

6. Hagopian A, Zuyderduin A, Kyobutungi N, Yumkella F. Job Satisfaction and morale in the ugandan health workforce. Health Affairs (2009) 28:w863−75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w863

7. Bradshaw YW, Ndegwa SN. The Uncertain Promise of Southern Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (2000).

Google Scholar

8. Dicker RC. Case studies in applied epidemiology. Pan Afr Med J. (2017) 27 (Suppl. 1):1. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.1.12886

9. Yunus M, Karim HR, Bhattacharyya P, Ahmed G. Comparison of effectiveness of class lecture versus workshop-based teaching of basic life support on acquiring practice skills among the health care providers. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci . (2016) 6:61–4. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.183018

10. Faisal R, Rehman Kur, Bahadur S, Shinwari L. Problem-based learning in comparison with lecture-based learning among medical students. J Pakistan Med Assn . (2016) 66:650–3.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

11. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: Teaching by Case Method (2018). Available online at: www.hsph.harvard.edu/ecpe/programs/teaching -by-case-method (Accessed Aug 13, 2018).

12. Sibbald SL, Speechley M, Amardeep T. Adapting to the needs of the public health workforce: an integrated case-based training program. Front Public Health (2016) 4:221. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00221

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

13. Baseman JG, Marsden-Haug N, Holt VL, Stergachis A, Goldoft M, Gale JL. Epidemiology competency development and application to training for local and regional public health practitioners. Pub Health Rep . (2008) 123 (Suppl 1):44–52. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S111

14. Andresen L, Boud D, Cohen R. Experience based learning. In: Foley, G editor. Understanding Adult Education and Training , 2nd ed. Sydney, NSW: Allen and Unwin (2001). p. 225–39.

15. PAHO. Measles Elimination Field Guide. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: PAHO (2005) Available online at: http://www1.Paho.Org/English/Ad/Fch/Im/Fieldguide_Measles.Pdf

16. Zemke R, Zemke S. Adult learning: what do we know for sure? ERIC (1995) 32:31–4.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, workforce development, training, case study

Citation: Nelson AL, Bradley L and MacDonald PDM (2018) Designing an Interactive Field Epidemiology Case Study Training for Public Health Practitioners. Front. Public Health 6:275. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00275

Received: 02 July 2018; Accepted: 05 September 2018; Published: 26 September 2018.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2018 Nelson, Bradley and MacDonald. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amy L. Nelson, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Cases Studies in Public Health Available Online

First study of mers animal host in saudi arabia.

Case studies aren’t just for business schools anymore. Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health has been using the case method to teach MPH students as part of the new Columbia Public Health Curriculum. Now, six of the School’s public health cases have been published online, making them available to classrooms anywhere.

“The case method can be a powerful tool for learning public health. It gives students the opportunity to gain experience making decisions in the face of uncertainty, much as they will have to do every day when they graduate and leave us to work in their chosen field,” says Melissa Begg, ScD , Vice Dean for Education at the Mailman School, who is leading the implementation of the new MPH curriculum.

Each case study tells a detailed story which stops mid-action, asking students to imagine themselves into the shoes of a decision-maker facing a tough call. One case developed with the help of David Abramson, PhD , assistant professor of Sociomedical Sciences, looks at the decision of whether to evacuate two hospitals during Superstorm Sandy. Another looks at how to win a community’s trust, as told through the experience of Mailman scientists conducting a federally-funded study of arsenic-tainted water in Bangladesh.

Classroom discussions are lively, and most important, there isn’t a single right answer. “Students practice taking positions and defending them based on the available evidence, while developing communication and critical thinking skills,” explains Dr. Begg. “They learn to argue persuasively for their points of view.

The Mailman School case studies are available through Columbia University’s Case Consortium website, which also features cases by Columbia’s Journalism School and the School for International and Public Affairs (SIPA). They are available free (after registration) to educators and at a nominal cost to students, professionals, and other interested parties.

“While most existing case curriculum remains paper-based, the Mailman School cases are online and multimedia, meeting students where they live in the digital media world,” says Kirsten Lundberg, MPA, director of the Case Consortium @ Columbia.

The “discussion-based” case study approach has historic roots reaching back to Socrates, and was popularized in the 20th century by business schools. To see the cases, please visit Case Consortium and click on Cases.

Public Health Case Studies

Voluntary or Regulated? The Trans Fat Campaign in New York City

This case takes students behind the scenes in the world of public health policymaking. Students follow the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and the process it went through to craft a policy to reduce public consumption of trans fats in restaurants. In 2005, after considerable internal negotiations, the department’s Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Control elected to launch a public awareness campaign aimed equally at consumers, restaurants and their suppliers. But after a year, the awareness campaign had not budged the rate of trans fat use in restaurants. In 2006, the department decided to resort to regulation, despite the risks of triggering protests of a “nanny state,” not to mention pushback from industry.

When BEST Intentions Go Awry: Arsenic Mitigation in Bangladesh

This case is about a public health response to the widespread arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh. It examines the lead-up to a 2008 media crisis that confronted a Columbia University clinical trial of a potential treatment for arsenic poisoning. The case raises for discussion the challenges of conducting research in rural, less developed and culturally insular communities. It also asks how to help communities while studying them—complicated by funding restrictions and a possible skewing of results.

Community Savings, or Community Threat? California Policy for Ill and Elderly Inmates

This case looks at the challenges that confront public health professionals who work in a corrections environment. By 2011, a court-appointed Receiver had made progress in fixing a broken system of medical care for prisoners in California. But costs spiraled ever higher for elderly and ailing inmates. Public health officials had to balance competing public priorities: save taxpayer dollars while treating patients. A new law allowed the sickest prisoners to move to community-based care—but now public health doctors had to decide: who qualified for medical parole?

Credible Voice: WHO-Beijing and the SARS Crisis

This case study takes students into the Beijing office of the World Health Organization as it dealt with the SARS crisis in early 2003. The WHO serves as the world’s monitor of disease outbreak and control. It is able to mobilize legions of the world’s best scientists to analyze, diagnose, prescribe treatments for and contain diseases. However, it depends on the cooperation of the countries experiencing an epidemic. What happens when that cooperation is limited or nonexistent?

The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker

This case explores the ethical and logistical challenges that doctors face when an infectious disease patient does not cooperate with advice to stay out of public spaces in order to protect the general welfare. In April 2007, a young Atlanta lawyer, Andrew Speaker, was diagnosed with active tuberculosis. Initially cooperative, Speaker departs without notice for Greece and his scheduled wedding even though it is clear that his strain of TB is more lethal and difficult-to-treat than anticipated.

Evacuate or Stay? Northshore LIJ and Hurricane Sandy

This case examines the pros and cons of evacuating medical facilities in the face of a looming natural disaster. In October 2012, the North Shore-Long Island Jewish Hospitals (North Shore-LIJ) network braced—together with rest of the East coast—for the advent of Hurricane Sandy. Weather forecasters painted a grim picture, and North Shore-LIJ had three hospitals in low-lying areas. Vice President of Protective Services James Romagnoli and COO Mark Solazzo had seen this scenario only a year earlier, when in August 2011 they evacuated hospitals in advance of Hurricane Irene. But Irene had, at the last moment, spared New York City. With that unnecessary evacuation fresh in their minds, the two officials had to decide what to do as Sandy approached.

- Utility Menu

harvardchan_logo.png

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Case-Based Teaching & Learning Initiative

Teaching cases & active learning resources for public health education, case writing.

An overview of the case planning and writing process, by experienced case-writer and CBTL workshop leader Kirsten Lundberg.

2019. The Case Centre . Visit website A non-profit clearing house for materials on the case method, the Case Centre holds a large and diverse collection of cases, articles, book chapters and teaching materials, including the collections of leading business schools across the globe.

Austin, J. , 1993. Teaching Notes: Communicating the Teacher's Wisdom , Harvard Business School Publishing. Publisher's Version "Provides guidance for the preparation of teaching notes. Sets forth the rationale for teaching notes, what they should contain and why, and how they can be prepared. Based on the experiences of Harvard Business School faculty."

Abell, D. , 1997. What makes a good case? . ECCHO–The Newsletter of the European Case Clearing House , 17 (1) , pp. 4-7. Read online "Case writing is both art and science. There are few, if any, specific prescriptions or recipes, but there are key ingredients that appear to distinguish excellent cases from the run-of-the-mill. This technical note lists ten ingredients to look for if you are teaching somebody else''s case - and to look out for if you are writing it yourself."

Roberts, M.J. , 2001. Developing a teaching case (abridged) , Harvard Business School Publishing. Publisher's Version A straightforward and comprehensive overview of how to write a teaching case, including sections on what makes a good case; sources for and types of cases; and steps in writing a case.

- Writing a case (8)

- Writing a teaching note (4)

- Active learning (12)

- Active listening (1)

- Asking effective questions (5)

- Assessing learning (1)

- Engaging students (5)

- Leading discussion (10)

- Managing the classroom (4)

- Planning a course (1)

- Problem-based learning (1)

- Teaching & learning with the case method (14)

- Teaching inclusively (3)

- MEMBER DIRECTORY

- Member Login

- Publications

- Clinician Well-Being

- Culture of Health and Health Equity

- Fellowships and Leadership Programs

- Future of Nursing

- U.S. Health Policy and System Improvement

- Healthy Longevity

- Human Gene Editing

- U.S. Opioid Epidemic

- Staff Directory

- Opportunities

- Action Collaborative on Decarbonizing the U.S. Health Sector

- Climate Communities Network

- Communicating About Climate Change & Health

- Research and Innovation

- Culture of Health

- Fellowships

- Emerging Leaders in Health & Medicine

- Culture & Inclusiveness

- Digital Health

- Evidence Mobilization

- Value Incentives & Systems

- Substance Use & Opioid Crises

- Reproductive Health, Equity, & Society

- Credible Sources of Health Information

- Emerging Science, Technology, & Innovation

- Pandemic & Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Preparedness and Response

- Preventing Firearm-Related Injuries and Deaths

- Vital Directions for Health & Health Care

- NAM Perspectives

- All Publications

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- MEMBER HOME

Systems Thinking for Public Health: A Case Study Using U.S. Public Education

ABSTRACT | The initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States largely focused on addressing the immediate health consequences from the emergent pathogen. This initial focus often ignored the related impacts from the pandemic and from mitigation measures, including how existing social determinants of health compounded physical, social, and economic impacts on individuals who have historically been marginalized. The consequences of decisions around closing and reopening primary and secondary (K–12 in the United States) public schools exemplify the complex impacts of pandemic mitigation measures. Ongoing COVID-19 mitigation and recovery efforts have gradually begun addressing indirect consequences, but these efforts were slow to be identified and adopted through much of the acute phase of the pandemic, mirroring the decades-long neglect of contributors to the overall health and well-being of populations that have been made to be vulnerable.

A systems approach for decision-making and problem solving holistically considers the effects of complex interacting factors. Taking a systems approach at the start of the next health emergency could encourage response strategies that consider various competing public health needs throughout different sectors of society, account for existing disparities, and preempt undesirable consequences before and during response implementation. There is a need to understand how a systems approach can be better integrated into decision-making to improve future responses to public health emergencies. A wide range of stakeholders should contribute expertise to these models, and these partnerships should be formed in advance of a public health emergency.

Introduction

In September 2021 the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop titled “Towards a Post-Pandemic World: Lessons from COVID-19 for Now and the Future.” (NASEM, 2022) In this article, select workshop participants further explore the application of systems thinking in evaluating COVID-19 mitigation measures.

Systems Thinking in Public Health

A systems science approach to outbreak response planning is a useful tool for broadening strategic thinking to consider critical factors driving the short- and long-term consequences of crisis response measures, including how such decisions will impact health disparities (Bradley et al., 2020). A conceptual framework, systems thinking accounts for the relationship between individual factors within a scenario as well as their contributions to the whole, and can facilitate the synthesis of response plans that match the scale and complexity of the problem at hand (Trochim et al., 2006).

Specifically for public health, a systems approach “applies scientific insights to understand the elements that influence health outcomes; models the relationships between those elements; and alters design, processes or policies based on the resultant knowledge” (Kaplan et al., 2013). Complex and interconnected risk factors collectively influenced health outcomes in the COVID-19 pandemic. Response to an evolving public health emergency requires a systems approach that can weigh disparate needs and account for systemic inequities to quickly generate solutions while remaining adaptable as new data emerges.

In this article, we use the issue of K–12 public school closures in the United States to illustrate the need for systems approaches in public health situations. Mapping tools, such as causal loop diagrams, can show the complexity of interconnected factors and their use should be prioritized to guide evidence-based decisions in complex and evolving circumstances. This article argues for the adoption of a systems science approach to outbreak decision-making that:

- addresses the inherent complexity of societal impacts during public health emergencies,

- accounts for social determinants of health, and

- includes perspectives from a wide range of stakeholders

COVID-19 Decision-Making and Unintended Consequences