- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Talking About Ethics Across Cultures

- Mary C. Gentile

Five ways to help people act on their values, no matter the context.

A few years ago, I was teaching a two-day program about ethics in India for entrepreneurs and business faculty who taught entrepreneurship. It was a program that I had spent years honing, building upon research that suggests rehearsing — pre-scripting, practicing voice, and peer coaching — is an effective way to build the moral muscle memory, competence, confidence, and habit to act ethically. Rather than simply preaching and pretending, we wanted to address the day-to-day realities that create pressure to act unethically even when employees know and want to do better.

- MG Mary C. Gentile is the creator and director of the Giving Voice to Values pedagogy for values-driven leadership and formerly the Richard M. Waitzer Bicentennial Professor of Ethics at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business.

Partner Center

Cultural Diversity and Universal Ethics in a Global World

Introduction.

- Published: 07 August 2013

- Volume 116 , pages 681–687, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Domènec Melé 1 &

- Carlos Sánchez-Runde 1

65k Accesses

33 Citations

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cultural diversity and globalization bring about a tension between universal ethics and local values and norms. Simultaneously, the current globalization and the existence of an increasingly interconnected world seem to require a common ground to promote dialog, peace, and a more humane world. This article is the introduction to a special issue of the Journal of Business Ethics regarding these problems. We highlight five topics, which intertwine the eight papers of this issue. The first is whether moral diversity in different cultures is a plausible argument for moral relativism. The second focuses on the possibility of finding shared values and virtues worldwide. The third topic deals with convectional universalistic ethical theories in a global world and the problems they present. Fourth, we consider the traditional natural moral law approach in the context of a global world. The last topic is about human rights, as a practical proposal for introducing universal standards in business.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Differences in race, sex, language, ethnicity, values systems, religion, and local practices are important aspects of the business environment in both domestic and international business. Cultural diversity not only matters to business management, but also to policy makers and international organizations. It is, of course, relevant for business ethics, too. Organizing corporations so that people from different cultures live and work together peacefully is a challenge for management that we cannot ignore.

The last few decades have witnessed the development of cross-cultural management, which focuses on cultural differences and their effect on organizational and managerial decision-making. Cross-cultural management is not only a question of techniques. It involves human and ethical considerations, as does every other aspect of management (Melé 2012 ). Beyond cultural diversity, management is about people and so it entails ethical dimension.

Cultural diversity entails an ethical challenge, for different reasons. One is that there are differences on moral perceptions and moral judgments among cultures, and consequently a tension appears between moral universalism (universal ethical principles or standards) and moral cultural relativism (local or cultural ethical norms as the exclusive source for ethical standards) (Donaldson 1996 ; Jhingran 2001 ; Frederick 2002 ; Vendemiati 2008 ; among others). Some may defend that the old chestnut, “when in Rome do as Romans do,” still has currency. This saying does not offer ethical difficulties if you apply it with regard to certain customs, but it is problematic if you apply it to ethical matters—then it leads to moral relativism. At the other extreme we find those who defend acting in accordance with one’s home cultural values and norms, which often merits the accusation of “cultural imperialism.” Others, to avoid both cultural relativism and imperialism, prefer to say “when in Rome do as the best Romans do.” This improves the former by introducing a sense of discernment, but no-one can be sure that even the best Romans always acted in accordance with high standards of morality. We should remember, for instance, that for a long time slavery was acceptable even for the best Romans, and in certain countries or places corruption was so extensive that it would have been very difficult to find a virtuous person abstaining from corrupting practices. Apart from this, acritically accepting other people’s behavior, or the values of the majority, as one’s moral standard means ignoring personal conscience and thus the first personal moral obligation of sincerely seeking the virtuous and right thing to do in each situation.

In spite of these and other objections, some ethicists are in favor of moral relativism, while others insist on the shortcomings of this position and defend moral universalism (Krausz 1989 ). A third group holds a balanced position between universalism, expressed through a set of basic ethical values or principles, and particular cultural norms (Donaldson 1996 ; Gowans 2012 ) or are looking for empirical or philosophical bases to promote global ethics (e.g., Küng 1998 and ITC 2009 , respectively).

The debate on ethical relativism and universal ethics, which is still open, has important consequences for both business ethics and cross-cultural management. Some opt for accepting ethical relativism, while others offer strong arguments against this. In addition, some events, such as corporate scandals and corruption, violation of certain basic human rights and environmental issues question ethical relativism at least in some matters.

Apart from this debate, there is a pragmatic reason to seek and promote universalism and common values: the current globalization and the existence of an increasingly interconnected world. According to Bok, “the need to pursue the inquiry about which basic values can be shared across cultural boundaries is urgent, if societies are to have some common ground for cross-cultural dialog and for debate about how best to cope with military, environmental, and other hazards that, themselves, do not stop at such boundaries.” ( 2002 , p. 13).

The Parliament of the World’s Religions ( 1993 ), seeking consensus on common ethical values, stated that there will be no better global order without a global ethic, which cannot be created or enforced by laws, prescriptions, or conventions alone. On its part, the International Theological Commission (ITC) praised those who work in seeking common ethical values, assessing that “only the recognition and promotion of these ethical values can contribute to the construction of a more human world.” But, at the same time, stresses the necessity of achieving a sound foundation by affirming: “these efforts cannot succeed unless good intentions rest on a solid foundational agreement regarding the goods and values that represent the most profound aspirations of man, both as an individual and as member of a community.” (ITC 2009 , n. 2).

These and other related topics were discussed in the 17th IESE International Symposium on “Ethics, Business and Society,” in Barcelona, Spain, on May 14–15, 2012 under the theme “Universal Ethics, Cultural Diversity and Globalization.” This issue of the Journal of Business Ethics publishes a collection of papers presented at this Symposium. Our aim is to introduce the articles selected within a framework on cultural diversity and universal ethics intertwining the contributions included in this issue. We structure this presentation by focusing on five relevant aspects treated in the Symposium. Firstly, we ask whether or not moral diversity of different cultures is a good argument for moral relativism. Secondly, we consider the existence of shared values and virtues worldwide, and some managerial inferences. Thirdly, we wonder if universalistic ethical theories are appropriate in a global world facing development problems. Fourthly, we deal with the traditional proposal of natural moral law in the context of a global world. In the fifth part, we focus on human rights, as a practical proposal for introducing universal standards in business.

Is Moral Diversity a Good Argument for Moral Relativism?

Moral diversity among cultures is not a novelty. Among the ancient Greek philosophers, moral diversity was widely acknowledged (Gowans 2012 ), as it was with Medieval thinkers, like Thomas Aquinas (das Neves and Melé 2013 ). Modern cultural anthropologists have also empirically shown that moral diversity is a matter of fact (e.g., Benedict 1934 ). A fundamental question is whether the existence of moral diversity is a good argument to support moral relativism. While the former is peacefully accepted by almost all, many reject ‘moral relativism, or more precisely “normative moral relativism.” Moral relativists defend the position that there are neither objective ethics nor universal ethics; the only source of truth for morality is each cultural context. According to Gowans ( 2012 ), moral relativists state that “the truth or falsity of moral judgments, or their justification, is not absolute or universal, but is relative to the traditions, convictions, or practices of a group of persons.” He terms this philosophical position “Metaethical Moral Relativism.” This author explains this approach through the statement “Polygamy is morally wrong,” which may be true relative to one society, but false relative to another. Similar examples could include cutting off a hand when someone is caught stealing, the mutilation of female genitals, or in a business context, tolerating bribery and harming the environment. Obviously, one can claim that these actions are assumed as right in reference to norms shared in certain societies that endorse them, but this does itself not probe by itself the truth of a moral judgment, especially when colliding with solid trans-cultural ethical referents, such as respect of human dignity or the Golden Rule. A moral judgment may be passed in one society, but not in another, this being a matter for sociological verification. But this is not the same as justifying and legitimating a given moral judgment as good or right.

Two papers here deal with moral relativism, although this is not their central topic. From different perspectives, both agree that moral diversity is not a good argument for moral relativism. The first paper is authored by Carlos J. Sanchez-Runde, Luciara Nardon, and Richard M. Steers, all with expertise in cross-cultural management. They describe and discuss the cultural roots of ethical conflicts in the global business environment. They emphasize the importance of understanding moral diversity along with ethical conflicts in multiple levels within the same organization or industry, and the meaning of universal values and the relationship between values and practices. These authors state that values are universal but their universalism can only be accessed incrementally. They bring a text on the effects of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima from the literature Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oé to illustrate the point that the richness of the concept of human dignity is beyond words, that no human language will ever fully make it justice, and that one can improve its understanding through time and space. They argue that people and cultures evolve over time and space, and so do their ethical beliefs and values. At times, these values run somewhat in tandem across cultures to give the impression of a universal form of access—understanding and application—to those values. This can be seen very clearly in many commonly espoused beliefs (respect your neighbors, protect the defenseless…) that can be found in various religions. At other times, however, this convergence seems to disappear. Their conclusion is that from a descriptive viewpoint, ethical values are not universal over time and space but they do become universal through time and space. We then make progress in accessing ethical values.

The second paper, by Daryl Koehn, devotes a part of its discussion to clarifying some mistaken notions that lead to cultural ethical relativism. One is that moral relativists often begin by pointing to the wide variety of human experience, and no one contests the existence of such variety. This happens because of focusing too much on the details and failing to search for overarching ethic good and/or virtues underpinning diverse human practices. Another objection against some moral relativists is that they consider cultures as static and monolithic, when actually they are not. Some members of a culture may be more practically wise than others, and each culture contains resources and concepts for interpreting a universal virtue such as justice in a variety of ways in light of new conditions and circumstances. Over time –she affirms–, “these intra-cultural manifestations may converge as agents refine their judgments in light of experience interpreted by reason and in light of arguments advanced by especially thoughtful members of the community.” A third argument given by Koehn is that moral relativists wrongly assume that issues can only be successfully addressed in one way within another culture. This assumption leads them to conclude wrongly that this other culture operates with an ethical compass different from our own. This has a significant application in business when some affirm that it is morally acceptable to pay bribes when doing transactions in Asia. Many Scandinavian companies, for instance, do business in Asia without paying bribes.

Common Values Worldwide and Universal Virtues

While moral diversity is a matter of fact, as noted, some add that disagreements across different societies are much more significant than whatever agreements there may be—this is called “Descriptive Moral Relativism” (Gowans 2012 ). Authors in disagreement with this proposition point that there is a universal minimal morality, whatever other moral differences there may be (e.g., Bowie 1990 ; Walzer 1994 ; Bok 2002 ). According to this latter scholar, “certain basic values necessary for collective survival have had to be formulated in every society. A minimalist set of such values can be recognized across societal and other boundaries.” (Bok 2002 , p. 12).

Several empirical research works show that beyond specific moral judgments there can be found basic values or principles underlying those judgments, and these common values and principles appear in the major religions and wisdom traditions worldwide. Thus, Lewis ( 1987 ) and Moses ( 2001 ) identified a number of foundational principles shared by all religions, the Golden Rule (Wattles 1996 ) among others (Terry 2011 ; Tullberg 2011 ). Other findings recognize the more or less latent presence of common values in when surveying the world’s major religious traditions (Kidder 1994 ; Dalla Costa 1998 ; Küng 1996 ; 1998 ). Hengda ( 2010 ), for instance, traced within Chinese traditional ethics (Confucius, Mencius, MoTzu…) the universal values of humanity and reciprocity included in the Declaration toward a Global Ethics of Humanity. This Declaration was formulated by the Second Parliament of the World’s Religions, which 6,500 delegates from all over the world attended in Chicago in 1993.

If we look at the great diversity of character traits presented as virtues throughout history and societies, Dahlsgaard et al. ( 2005 ) found a set of core virtues across religions and cultures (Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Athenian, Judeo-Christian, Islamic, among others). Their findings show that there is convergence across time, place and intellectual tradition about certain core virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, temperance, humanity, and transcendence. These core virtues are “ubiquitous, if not universal” (Peterson and Seligman 2004 , p. 33), and they are not too far from the four traditional “cardinal virtues” proposed firstly by Plato (Finance 1991 , p. 485) and then on by many other authors: prudence (practical wisdom), justice, fortitude (courage), and temperance (moderation or self-control).

Two papers of this issue focus on universal virtues. Daryl Koehn, apart from the above-mentioned discussion on moral relativism, also shows how Aristotle’s virtue ethic strongly resembles that of Confucius. This similarity derives from what they each take to be objective facts about human nature and developmental aspects of virtue. This similarity suggests that a universal virtue ethic may already exist in the form of a powerful shared strand of moral thinking. Morales and Cabello focus on the traditional cardinal virtues, which they consider universal and essential moral competencies for managerial decision-making. They discuss the influence of these virtues on moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character. Prudence will influence moral sensitivity, moral judgment, and moral motivation. Justice will influence the component of the ethical decision-making process mainly related with human will: moral motivation and moral character. Temperance will help to create moral motivation to develop ethical behavior. Finally, fortitude will reinforce the moral character to engage the ethical behavior.

Moral Universalism

In opposition to moral relativism, moral universalism —also called moral objectivism —holds that there are objective right or wrong actions, independently of the social or personal values or opinions. There are well-known approaches in business ethics which fall within the domain of moral universalism, such as Kantian deontology, Natural Rights Theory, Utilitarianism, and several forms of Contractualism. Moral universalism can be, or not, moral absolutism. This latter, as in Kantian Ethics (Bowie 1999 ), defends the position that the morality of some actions is independent of context or consequences. Non-absolutist moral universalism, such as Consequentialism and its more popular form, Utilitarianism (Snoeyenbos and Humber 2002 ), or Integrative Social Contracts Theory (Donaldson and Dunfee 1999 ) consider both universal norms and local norms to evaluate the morality of an action.

Universalist theories like these mentioned provide sound ethical standards or criteria for conducting business, but they also present some problems. Some of them are based on different aprioristic rational principles (the Categorical Imperative in Kant, the Utilitarian principle in Utilitarianism, and so on). Thus, various ethical theories compete. In addition, Neo-Aristotelians criticize agent-neutral theories for not considering individual character in making moral judgments.

Moral universalism is indirectly considered in the article by Prabhir Vishnu Poruthiyil, included in this issue, from a critical position. He argues that business ethicists—many of whom propose universal theories—state obligations for multinationals which could contribute to the well-being of individuals in developing countries. In addition, some of them have offered strategies to achieve this goal. However, their results are limited. Despite the good intentions, business ethics theories aiming at fulfilling social goals can be rendered ineffectual when economic goals are prioritized. He then postulates a “developmental ethics” approach calling on multinational companies to change their primary focus from profit generation to social justice. He argues that this approach, opposed to mere economism, offers more nuanced approaches than those now available in business ethics literature.

Universal Ethics through the Natural Moral Law

A different perspective on universal ethics come from the natural moral law tradition (Murphy 2011 ), with roots in several authors of ancient Greece and Rome including Cicero, and medieval thought, particularly Thomas Aquinas’. Natural law is mentioned in the Bible ( 1966 ), as rationally accessible for unbelievers. St. Paul writes: “When Gentiles, who do not have the law, do by nature things required by the law, they are a law for themselves, even though they do not have the law. They show that the requirements of the law are written on their hearts, their consciences also bearing witness, and their thoughts sometimes accusing them and at other times even defending them.” ( Rom 2: 14-15).

Cicero suggested the existence of a Reason ( mens , in Latin) that rules the whole world, which he describes as a fully superior and divine, not mediated, “nature law” ( lex naturae ) that is universal, absolutely primal, invariable and eternal, which humans should try to know and apply in their lives (Corso de Estrada 2008 ). Cicero is aligned with the Stoic moral philosophy view of the natural law when he synthesized that “living according to nature consists in living according to the dictates of right reason, which is quite clearly thought of as the common or universal law” (Horsley 1978 , p. 40).

Similarly, although with some differences to Cicero, Aquinas accepted human beings are endowed with certain capacity (practical reason) that allows us to distinguish good from evil—what is truly good for human flourishing from what is not—at least in some minimalistic aspects. Thus, humans can know natural law, which “is nothing else than the rational creature’s participation of the eternal law.” (Aquinas 1981 , I-II 91, 2) Aquinas focused on the rational nature of the human being and consequently his natural law theory is directly founded on the basic elements of humanity. It is a universal ethics which also accounts for diversity. In addition, Cicero held that natural law obliges us to contribute to the general good of the larger society (Barham 1841 -42, Introduction). Aquinas also included moral responsibilities toward the common good of the society (Finnis 1998 , pp. 234ff).

After a period of certain decadence and criticism (George 1999 ), natural law theory has experienced a revival since the middle of the last century (Maritain 1971 , 2001 ; Finnis 1980 ; Rhonheimer 2000 ; Murphy 2001 , among others), and some recently suggest a new look at natural law (ITC 2009 ), including Pope Benedict XVI ( 2008 ) in his speech to the General Assembly of the United Nations. He related the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 to natural law by affirming that “the rights recognized and expounded in the Declaration apply to everyone by virtue of the common origin of the person, who remains the high-point of God’s creative design for the world and for history. They are based on the natural law inscribed on human hearts and present in different cultures and civilizations.” (our Italics).

In this issue, two papers refer to natural law, one focused on Cicero and another on Aquinas. Cicero’s natural law and his ideas on virtuous behavior are taken into consideration by Michael Aßländer in his contribution. He focuses on Cicero by arguing that this Roman Stoic philosopher presented important concepts and approaches from which we can learn for business ethics. After summarizing the specific Ciceronian understanding of natural law and virtuous behavior, he analyzes honorableness and beneficialness, two key distinct qualities according to Cicero. This Roman thinker had the conviction that honorableness depends on respecting universal ethical principles. Wise people, following their true nature, fulfill their natural duties toward fellow-citizens and do no harm others. For Cicero, Aßländer affirms, what is honorable is always useful, because the honorable person strives for the common good, and therefore serves the community and benefits all. He argues that, from a Ciceronian perspective, what is honorable may not necessarily be profitable; honorable behavior and profitable behavior may conflict. Aßländer argues that reputation must be seen as an independent issue which might influence financial opportunities but, first of all, derives from the fulfillment of duties that go beyond purely economic considerations. Reputation derives solely from honorable behavior and the orientation toward the common good. Consequently, corporate reputation will only be achieved if it is based primarily on “honorableness,” and that reputation will be lost if financial interests override the honest intentions of a company.

Human Rights as Universal Standards for Business

One important step in applying universal ethics is through human rights, and more specifically the international declarations of human rights, beginning with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (1948), and followed by other UN human rights covenants and ILO Conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1966, along with an optional protocol added in 2008, which presents an exhaustive list of rights in the labor context, and the UN Global Compact with its ten ethical principles for business.

Article 1 of the UDHR begins with the well-known statement that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act toward one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” This is a significant ethical statement addressed to humankind. However, the proposal presents two important issues to be debated, one theoretical and the other practical. The theoretical regards the foundation of human rights. As the Declaration of the Parliament of the World’s Religions ( 1993 ) pointed out, rights without morality cannot long endure. Without a solid foundation, any claim supported by strong lobbies can eventually be presented as a human right. The practical problem refers to the implementation of human rights and the role that business should play in this matter. At this point, it is worth noting the recent idea that protecting and promoting human rights is not only a task of states but also of civil society and business. We can point to, John Ruggie’s recent reports (Ruggie 2008 , 2011 , 2013 ) which former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan commissioned in 2005. The last of those reports, significantly entitled: “Protect, Respect, and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights” (Ruggie 2011 ) is particularly relevant for our purposes, as so are the “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights” to implement the Framework.

Two papers included in this special issue focus on Ruggie’s reports and the Guiding Principles. One is authored by Matthew Murphy and Jordi Vives. Drawing from several celebrated scholars, they hold that the equal treatment of all people as humans— conditio humana —is the constitutive, defining characteristic of universal human rights. Even accepting that ethical values may differ among cultures, seemingly divergent values converge at key points, such as respect for human dignity, respect for basic rights and good citizenship. In addition, human rights are the most important and fundamental category of moral rights that protect those freedoms which are most essential for a dignified and self-determined human life. Their main aim is, however, not to discuss this, but some problems related to Ruggie’s Framework. They apply concepts from the field of ‘organizational justice’ to the arena of business and human rights for the purpose of operationalizing this Framework. They argue that there could be a gap between perceptions of justice held by stakeholders versus businesses and/or the State. Through theoretical considerations and by analyzing a case study—the Goldcorp’s Marlin Mine in Guatemala—they show the potential for complicity of businesses in human rights abuses and expose a fundamental weakness in a UN Framework, that draws too sharp a distinction between duties of States and responsibilities of businesses.

The other paper, by Björn Fasterling and Geert Demuijnck analyses UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The authors identify tensions for corporations between respecting human rights as “perfect moral duty” admitting no exceptions and “human rights due diligence” to which companies should morally commit. They argue that the due diligence approach falls short of the requirements implied by the respect of human rights as perfect moral duty, inasmuch as the Guiding Principles leave room for an instrumental or strategic implementation of due diligence. This can then result in a depreciation of the fundamental norms the UN seeks to promote. They suggest that to make further progress in international and extraterritorial human rights law we also need a more forceful discussion on the moral foundations of human rights duties for corporations.

To conclude, we hope that this special issue may make a contribution to the current debate on cultural diversity and universal ethics, particularly in a global world, further discussion and research. Apart from academic research, ethics in culturally diverse and global environments may require the opening of closed attitudes too strongly secluded in technical and economics viewpoints, for they display certain disregard for what we have in common as humans. Benedict XVI once wrote that “as society becomes ever more globalized, it makes us neighbors but does not make us brothers.” ( 2009 , n. 16). Indeed, global and local processes, along with tensions of interconnectedness and separation do impact on the content and structure of human relationships. In our view, these relationships only become truly human by advancing in the current rebuilding of our common human family.

Aquinas, T. (1981)[1273]. Summa theologiae. London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, Ltd.

Barham, F. (1841–1842). Introduction to the political works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his treatise on the commonwealth; and his treatise on the laws. Translated from the original, with dissertations and notes (Vol. 2). London: Edmund Spettigue. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=747&Itemid=284 .

Benedict, R. (1934). Patterns of culture . New York: Penguin.

Google Scholar

Benedict XVI. (2008). Address to General Assembly of the United Nations Organization , April, 18 . Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/speeches/2008/april/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20080418_un-visit_en.html .

Benedict XVI. (2009). Encyclical Letter ‘Caritas in veritate’ . Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate_en.html .

Bible, The Holy. (1966). New revised standard version . Princeton, NJ: Scepter.

Bok, S. (2002). Common values . Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Bowie, N. E. (1990). Business ethics and cultural relativism. In P. Madsen & J. M. Shafritz (Eds.), Essentials of business ethics (pp. 366–382). New York: Meridian.

Bowie, N. E. (1999). Business ethics: A kantian perspective . Oxford: Blackwell.

Corso de Estrada, L. E. (2008). Marcus Tullius Cicero and the role of nature in the knowledge of moral good. In A. N. García, M. Šilar, & J. M. Torralba (Eds.), Natural law: Historical, systematic and juridical approaches (pp. 9–21). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of general psychology, 9 (3), 203–213.

Article Google Scholar

Dalla Costa, J. (1998). The ethical imperative: Why moral leadership is good business . Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers.

das Neves, J. C. and Melé D. (2013). Managing ethically cultural diversity: learning from Thomas Aquinas, Journal of Business Ethics. This issue.

Donaldson, T. (1996). Values in tension: Ethics away from home. Harvard Business Review, 74 (5), 48–57.

Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. (1999). Ties that bind: A social contracts approach to business ethics . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Finance, J. D. (1991). An ethical inquiry . Roma: Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana.

Finnis, J. (1980). Natural law and natural rights . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Finnis, J. (1998). Aquinas: Moral, political, and legal theory (founders of modern political and social thought) . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frederick, R. E. (2002). An outline of ethical relativism and ethical absolutism. In R. E. Frederick (Ed.), A companion to business ethics (pp. 65–80). Oxford: Blackwell.

Chapter Google Scholar

George, R. P. (1999). Defense of natural law . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gowans, C. (2012). Moral relativism. In E. N. Zalta (Eds.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy ( http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2012/entries/moralrelativism/ . Firstly published February 2004 and with a substantive revision in December 2009, and a minor correction in 2012.

Hengda, Y. (2010). Universal values and Chinese traditional ethics. Journal of International Business Ethics, 3 (1), 81–90.

Horsley, R. A. (1978). The law of nature in philo and cicero. Harvard Theological Review, 71 (1–2), 35–59.

ITC (International Theological Commission). (2009). In search of a universal ethic: A new look at the natural law. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/cti_documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20090520_legge-naturale_en.html ).

Jhingran, S. (2001). Ethical relativism and universalism . New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

Kidder, R. M. (1994). Universal human values. Futurist, 28 (4), 8–13.

Krausz, M. (Ed.). (1989). Relativism. Interpretation and confrontation . Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press.

Küng, H. (Ed.). (1996). Yes to a global ethic: Voices from religion and politics . New York, NY: Continuum.

Küng, H. (1998). A global ethics for global politics and economics . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, C. S. (1987). The abolition of man . London: Curtis Brown.

Maritain, J. (1971) [1943]. The rights of man and natural law . New York : Gordian Press.

Maritain, J. (2001). Natural law: Reflections on theory and practice . South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press.

Melé, D. (2012). Management ethics: Placing ethics at the core of good management . New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Moses, J. (2001). Oneness: Great principles shared by all religions . New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Murphy, M. C. (2001). Natural law and practical rationality . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Murphy, M. (2011). The natural law tradition in ethics. In E. N. Zalta (Eds.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy . Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/natural-law-ethics/ .

Parliament of the World’s Religions (1993) Declaration toward a global ethics —Chicago. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from www.weltethos.org/data-en/c-10-stiftung/13-deklaration.php .

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Rhonheimer, M. (2000). Natural law and practical reason: A Thomist view of moral autonomy . New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

Ruggie, J. G. (2008). Protect, respect and remedy: A framework for business and human rights. UN Doc A/HRC/8/5. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://198.170.85.29/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdf .

Ruggie, J. G. (2011). Guiding principles on business and human rights: Implementing the United Nations “protect, respect and remedy” framework . UN Doc A/HRC/17/31. Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Business/A-HRC-17-31_AEV.pdf .

Ruggie, J. (2013). Just business: Multinational corporations and human rights . London: WW Norton & Company.

Snoeyenbos, M., & Humber, J. (2002). Utilitarianism and business ethics. In R. E. Frederick (Ed.), A companion to business ethics (pp. 17–29). Oxford: Blackwell.

Terry, H. (2011). Golden rules and silver rules of humanity . Concord, MA: Infinite Publishing.

Tullberg, J. (2011). The golden rule of benevolence versus the silver rule of reciprocity, Journal of Religion and Business Ethics 3 (1). Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe/vol3/iss1/2 .

United Nations: 1948, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Retrieved February 25, 2013 from http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml .

Vendemiati, A. (2008). Universalismo e relativismo nell’etica contemporanea . Milano: Marietti.

Walzer, M. (1994). Thick and thin: Moral argument at home and abroad . Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Wattles, J. (1996). The golden rule . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

IESE Business School , Barcelona , Spain

Domènec Melé & Carlos Sánchez-Runde

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Domènec Melé .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Melé, D., Sánchez-Runde, C. Cultural Diversity and Universal Ethics in a Global World. J Bus Ethics 116 , 681–687 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1814-z

Download citation

Received : 03 March 2013

Accepted : 01 July 2013

Published : 07 August 2013

Issue Date : September 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1814-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cultural diversity

- Universal ethics

- Globalization

- Natural law

- Human rights

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

5.1 The Relationship between Business Ethics and Culture

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the processes of acculturation and enculturation

- Explain the interaction of business and culture from an ethical perspective

- Analyze how consumerism and the global marketplace might challenge the belief system of an organization

It has been said that English is the language of money and, for that reason, has become the language of business, finance, trade, communication, and travel. As such, English carries with it the values and assumptions of its native speakers around the world. But not all cultures share these assumptions, at least not implicitly. The sick leave or vacation policies of a British investment bank, for instance, may vary greatly from those of a shoe manufacturer in Laos. Because business and capitalism as conducted today have evolved primarily from European origins and profits are measured against Western standards like the U.S. dollar, the ethics that emerges from them is also beholden primarily (but not exclusively) to Western conceptions of behavior. The challenge for business leaders everywhere is to draw out the values of local cultures and integrate the best of those into their management models. The opportunities for doing so are enormous given the growing impact of China, India, Russia, and Brazil in global commerce. The cultures of these countries will affect the dominant business model, possibly even defining new ethical standards.

Business Encounters Culture

To understand the influence of culture on business ethics, it is essential to understand the concepts of enculturation and acculturation. In its most basic anthropological sense, enculturation refers to the process by which humans learn the rules, customs, skills, and values to participate in a society. In other words, no one is born with culture; all humans, regardless of their origin, have to learn what is considered appropriate behavior in their surrounding cultures. Whereas enculturation is the acquisition of any society’s norms and values, acculturation refers specifically to the cultural transmission and socialization process that stems from cultural exchange. The effects of this blending of cultures appear in both the native (original) culture and the host (adopted) culture. Historically, acculturation has often been the result of military or political conquest. Today, it also comes about through economic development and the worldwide reach of the media.

One of the earliest real estate deals in the New World exemplifies the complexity that results when different cultures, experiences, and ethical codes come into contact. No deed of sale remains, so it is difficult to tell exactly what happened in May 1626 in what is now Manhattan , but historians agree that some kind of transaction took place between the Dutch West India Company, represented by Pieter Minuit, the newly appointed director-general of the New Netherland colony, and the Lenape, a Native American tribe ( Figure 5.2 ). Which exact Lenape tribe is unknown; its members may have been simply passing through Manhattan and could have been the Canarsee, who lived in what is today southern Brooklyn. 1 Legend has it that the Dutch bought Manhattan island for $24 worth of beads and trinkets, but some historians believe the natives granted the Dutch only fishing and hunting rights and not outright ownership. Furthermore, the price, acknowledged as “sixty guilders” (about $1000 today), could actually represent the value of items such as farming tools, muskets, gun powder, kettles, axes, knives, and clothing offered by the Dutch. Clearly, the reality was more nuanced than the legend. 2

The “purchase” of Manhattan is an excellent case study of an encounter between two vastly different cultures, worldviews, histories, and experiences of reality, all within a single geographic area. Although it is a misconception that the native peoples of what would become the United States did not own property or value individual possession, it is nevertheless true that their approach to property was more fluid than that of the Dutch and of later settlers like the English, who regarded property as a fixed commodity that could be owned and transferred to others. These differences, as well as enforced taxation, eventually led to war between the Dutch and several Native American tribes. 3 European colonization only exacerbated hostilities and misunderstandings, not merely about how to conduct business but also about how to live together in harmony.

Link to Learning

For more information, read this article about the Manhattan purchase and the encounter between European and Native American cultures and also this article about Peter Minuit and his involvement. What unexamined assumptions by both parties led to problems between them?

Two major conditions affect the relationship between business and culture . The first is that business is not culturally neutral. Today, it typically displays a mindset that is Western and primarily English-speaking and is reinforced by the enculturation process of Western nations, which tends to emphasize individualism and competition. In this tradition, business is defined as the exchange of goods and services in a dedicated market for the purpose of commerce and creating value for its owners and investors. Thus, business is not open ended but rather directed toward a specific goal and supported by beliefs about labor, ownership, property, and rights.

In the West, we typically think of these beliefs in Western terms. This worldview explains the misunderstanding between Minuit, who assumed he was buying Manhattan, and the tribal leaders, who may have had in mind nothing of the sort but instead believed they were granting some use rights. The point is that a particular understanding of and approach to business are already givens in any particular culture. Businesspeople who work across cultures in effect have entered the theater in the middle of the movie, and often they must perform the translation work of business to put their understanding and approach into local cultural idioms. One example of this is the fact that you might find sambal chili sauce in an Indonesian McDonald’s in place of Heinz ketchup, but the restaurant, nevertheless, is a McDonald’s.

The second condition that affects the relationship between business and culture is more complex because it reflects an evolving view of business in which the purpose is not solely generating wealth but also balancing profitability and responsibility to the public interest and the planet. In this view, which has developed as a result of political change and economic globalization , organizations comply with legal and economic regulations but then go beyond them to effect social change and sometimes even social justice. 4 The dominant manufacture-production-marketing-consumption model is changing to meet the demands of an increasing global population and finite resources. No longer can an organization maintain a purely bottom-line mentality; now it must consider ethics, and, therefore, social responsibility and sustainability, throughout its entire operation. As a result, local cultures are assuming a more aggressive role in defining their relationship with business prevalent in their regions.

Had this change taken place four centuries ago, that transaction in Manhattan might have gone a little differently. However, working across cultures can also create challenging ethical dilemmas, especially in regions where corruption is commonplace. A number of companies have experienced this problem, and globalization will likely only increase its incidence.

Cases from the Real World

If you were to do a top-ten list of the world’s greatest corruption scandals, the problems of Petrobras ( Petróleo Brasileiro ) in Brazil surely would make the list. The majority state-owned petroleum conglomerate was a party to a multibillion-dollar scandal in which company executives received bribes and kickbacks from contractors in exchange for lucrative construction and drilling contracts. The contractors paid Petrobras executives upward of five percent of the contract amount, which was funneled back into slush funds. The slush funds, in turn, paid for the election campaigns of certain members of the ruling political party, Partido dos Trabalhadores , or Workers Party, as well as for luxury items like race cars, jewelry, Rolex watches, yachts, wine, and art. 5

The original investigation, known as Operation Car Wash ( Lava Jato) , began in 2014 at a gas station and car wash in Brasília, where money was being laundered. It has since expanded to include scrutiny of senators, government officials, and the former president of the republic, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The probe also contributed to the impeachment and removal of Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff. Lula and Rousseff are members of the Workers Party. The case is complex, revealing Chinese suppliers, Swiss bank accounts where money was hidden from Brazilian authorities, and wire transfers that went through New York City and caught the eye of the U.S. Department of Justice. In early 2017, the Brazilian Supreme Court justice in charge of the investigation and prosecution was mysteriously killed in a plane crash.

It is hard to imagine a more tragic example of systemic breakdown and individual vice. The loss of trust in government and the economy still affects ordinary Brazilians. Meanwhile, the investigation continues.

Critical Thinking

- Is there any aspect of the case where you think preventive measures could have been taken either by management or government? How would they have worked?

- Do you think this case represents an example of a culture with different business ethics than those practiced in the United States? Why or why not? How might corporations with international locations adjust for this type of issue?

Read this article about the Petrobras case to learn more.

Balancing Beliefs

What about the ethical dimensions of a business in a developed country engaging in commerce in an environment where corruption might be more rampant than at home? How can an organization remain true to its mission and what it believes about itself while honoring local customs and ethical standards? The question is significant because it goes to the heart of the organization’s values, its operations, and its internal culture. What must a business do to engage with local culture while still fulfilling its purpose, whether managers see that purpose as profitability, social responsibility, or a balance between the two?

Most business organizations hold three kinds of beliefs about themselves. The first identifies the purpose of business itself. In recent years, this purpose has come to be the creation not just of shareholder wealth but also of economic or personal value for workers, communities, and investors. 6 The second belief defines the organization’s mission , which encapsulates its purpose. Most organizations maintain some form of mission statement. For instance, although IBM did away with its formal mission statement in 2003, its underlying beliefs about itself have remained intact since its founding in 1911. These are (1) dedication to client success, (2) innovation that matters (for IBM and the world), and (3) trust and personal responsibility in all relationships. 7 President and chief executive officer (CEO) Ginni Rometty stated the company “remain[s] dedicated to leading the world into a more prosperous and progressive future; to creating a world that is fairer, more diverse, more tolerant, more just.” 8

Johnson & Johnson was one of the first companies to write a formal mission statement, and it is one that continues to earn praise. This statement has been embraced by several succeeding CEOs at the company, illustrating that a firm’s mission statement can have a value that extends beyond its authors to serve many generations of managers and workers. Read Johnson & Johnson’s mission statement and social commitment to learn more.

Finally, businesses also go through the process of enculturation ; as a result, they have certain beliefs about themselves, drawn from the customs, language, history, religion, and ethics of the culture in which they are formed. One example of a company whose ethics and ethical practices are deeply embedded in its culture is Merck & Co., one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies and known for its strong ethical values and leadership. As its founder George W. Merck (1894–1957) once stated, “We try to remember that medicine is for the patient. We try never to forget that medicine is for the people. It is not for the profits. The profits follow, and if we have remembered that, they have never failed to appear. The better we have remembered it, the larger they have been.” 9 Culture is deeply rooted, but businesses may make their own interpretations of its accepted norms.

Merck & Co. is justly lauded for its involvement in the fight to control the spread of river blindness in Africa. For more information, watch this World Bank video about Merck & Co.’s efforts to treat river blindness and its partnership with international organizations and African governments.

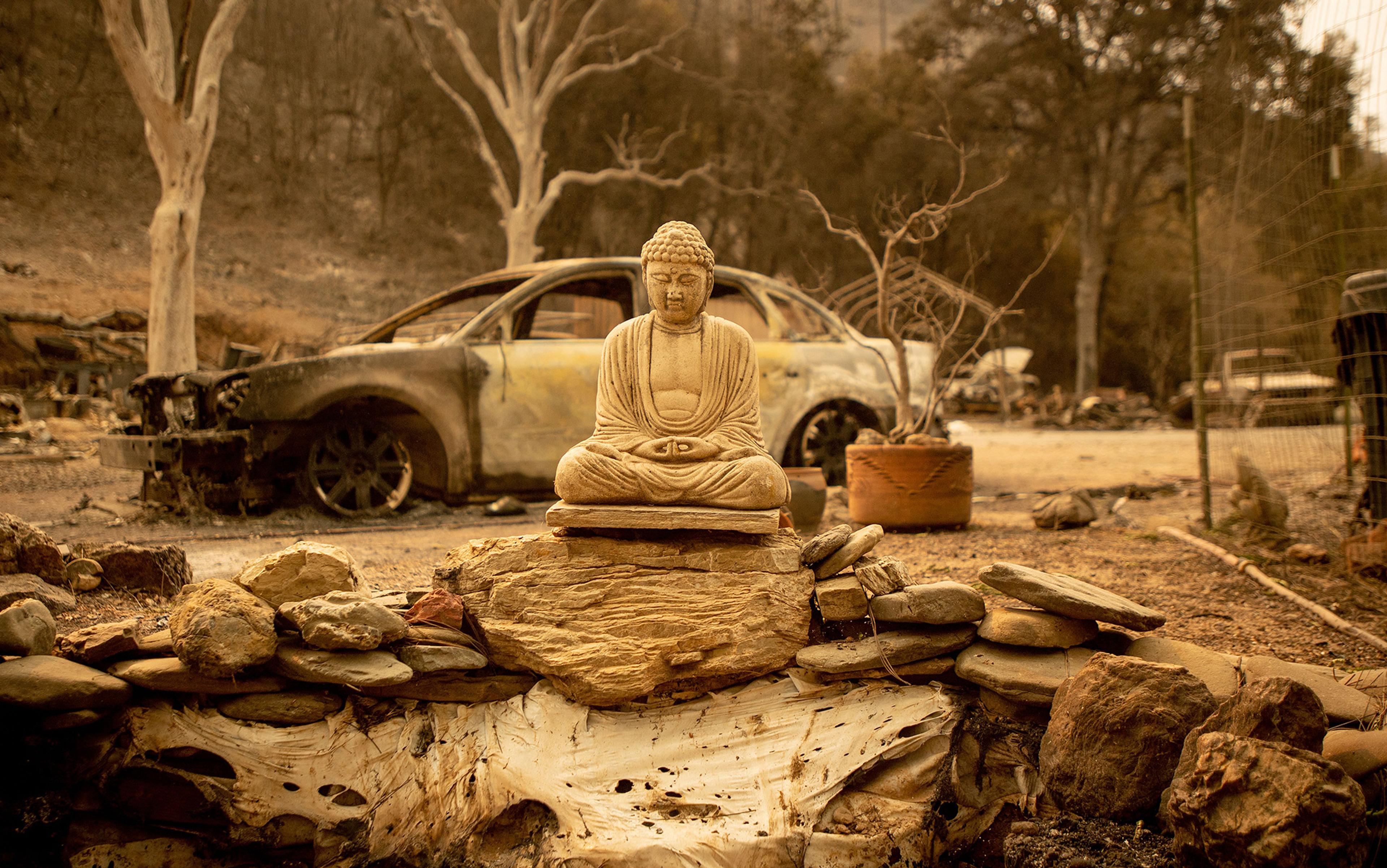

Our beliefs are also challenged when a clash occurs between a legal framework and cultural norms, such as when a company feels compelled to engage in dubious and even illegal activities to generate business. For example, the German technology company Siemens has paid billions of dollars in fines and judgments for bribing government officials in several countries. Although some local officials may have expected to receive bribes to grant government contracts, Siemens was still bound by national and international regulations forbidding the practice, as well as by its own code of ethics. How can a company remain true to its mission and code of ethics in a highly competitive international environment ( Figure 5.3 )?

Business performance is a reflection of what an organization believes about itself, as in the IBM and Merck examples. 10 Those beliefs, in turn, spring from what the individuals in the organization believe about it and themselves, based on their communities, families, personal biographies, religious beliefs, and educational backgrounds. Unless key leaders have a vision for the organization and themselves, and a path to achieving it, there can be no balance of beliefs about profitability and responsibility, or integration of business with culture. The Manhattan purchase was successful to the degree that Minuit and the tribal leaders were willing to engage in an exchange of mutual benefit. Yet this revealed a transaction between two very different commercial cultures. Did each group truly understand the other’s perception of an exchange of goods and services? Furthermore, did the parties balance personal and collective beliefs for the greater good? Given the distinctions between these two cultures, would that even have been possible?

Consumerism and the Global Marketplace

To paraphrase the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus (c. 535–475 BCE), the one constant in life is change. Traditional norms and customs have changed as the world’s population has grown more diverse and urbanized, and as the Internet has made news and other resources readily available. The growing emphasis on consumerism —a lifestyle characterized by the acquisition of goods and services—has meant that people have become defined as “consumers” as opposed to citizens or human beings. Unfortunately, this emphasis eventually leads to the problem of diminishing marginal utility, with the consumer having to buy an ever-increasing amount to reach the same level of satisfaction.

At the same time, markets have become more diverse and interconnected. For example, South Korean companies like LG and Samsung employ 52,000 workers in the United States, 11 and many U.S. companies now manufacture their products abroad. Such globalization of their domestic markets has allowed U.S. consumers to enjoy products from around the world, but it also presents ethical challenges. The individual consumer, for instance, may benefit from lower prices and a greater selection of goods, but only by supporting a company that might be engaged in unethical practices in its overseas supply or distribution chains. Producers’ choices about wages, working conditions, environmental impact, child labor, taxation, and plant safety feature in the creation of each product brought to market. Becoming aware of these factors requires consumers to engage in an investigation of the business practices of those parties they will patronize and exercise a certain amount of cultural and ethical sensitivity.

Overseas Manufacturing

How can the purchase of a pair of sneakers be seen as an ethical act? Throughout the 1990s, the U.S. shoe and sportswear manufacturer Nike was widely criticized for subcontracting with factories in China and Southeast Asia that were little more than sweatshops with deplorable working conditions. After responding to the criticisms and demanding that its suppliers improve their workplaces, the company began to redeem itself in the eyes of many and has become a model of business ethics and sustainability. However, questions remain about the relationship between business and government.

For instance, should a company advocate for labor rights, a minimum wage, and unionization in developing countries where it has operations? What responsibility does it have for the welfare of a contractor’s workers in a culture with differing customs? What right does any Western company have to insist that its foreign contractors observe in their factories the protocols required in the West? What, for example, is sacred about an eight-hour workday? When Nike demands that foreign manufacturers observe Western laws and customs about the workplace, arguably this is capitalist imperialism. Not only that, but Western firms will be charged more for concessions regarding factory conditions. Perhaps this is as it should be, but Western consumers must then be prepared to pay more for material goods than in the past.

Some argue that demanding that companies accept these responsibilities imposes cultural standards on another culture through economic pressure. Others insist there should be universal standards of humane employee treatment, and that they must be met regardless of where they come from or who imposes them. But should the market dictate such standards, or should the government?

The rise of artificial intelligence and robotics will complicate this challenge because, in time, they may make offshoring the manufacture and distribution of goods unnecessary. It may be cheaper and more efficient to bring these operations back to developed countries and use robotic systems instead. What would that mean for local cultures and their economies? In Nike’s case, automation is already a concern, particularly as competition from its German rival, Adidas, heats up again. 12

- What ethical responsibilities do individual consumers have when dealing with companies that rely on overseas labor?

- Should businesses adopt universal workplace standards about working conditions and employee protections? Why or why not?

- What would be required for consumers to have the necessary knowledge about a product and how it was made so that they could make an informed and ethical decision? The media? Commercial watchdog groups? Social-issues campaigns? Something else?

Read this report, “A Race to the Bottom: Trans-Pacific Partnership and Nike in Vietnam,” to learn more about this issue.

In considering the ethical challenges presented by the outsourcing of production to lower costs and increase profits, let us return to the example of IBM. IBM has a responsibility to provide technology products of high quality at affordable prices in line with its beliefs about client success, innovation, and trust. If it achieved these ends in a fraudulent or otherwise illegal way, it would be acting irresponsibly and in violation of both U.S. and host country laws and as well as the company’s own code of ethics. These constraints appear to leave little room for unethical behavior, yet in a globalized world of intense competition, the temptation to do anything possible to carve out an advantage can be overpowering. This choice between ends and means is reminiscent of the philosophers Aristotle and Kant, both of whom believed it impossible to achieve just ends through unjust means.

But what about consumer responsibility and the impact on the global community? Western consumers tend to perceive globalization as a phenomenon intended to benefit them specifically. In general, they have few compunctions about Western businesses offshoring their manufacturing operations as long as it ultimately benefits them as consumers. However, even in business, ethics is not about consumption but rather about human morality, a greater end. Considering an expansion of domestic markets, what feature of this process enables us to become more humane rather than simply pickier consumers or wasteful spenders? It is the opportunity to encounter other cultures and people, increasing our ethical awareness and sensitivity. Seen in this way, globalization affects the human condition. It raises no less a question than what kind of world we want to leave to our children and grandchildren.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Stephen M. Byars, Kurt Stanberry

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Business Ethics

- Publication date: Sep 24, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/business-ethics/pages/5-1-the-relationship-between-business-ethics-and-culture

© Mar 31, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Essay Guides

- Other Essays

- How to Write an Ethics Paper: Guide & Ethical Essay Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Other Guides

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

How to Write an Ethics Paper: Guide & Ethical Essay Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

An ethics essay is a type of academic writing that explores ethical issues and dilemmas. Students should evaluates them in terms of moral principles and values. The purpose of an ethics essay is to examine the moral implications of a particular issue, and provide a reasoned argument in support of an ethical perspective.

Writing an essay about ethics is a tough task for most students. The process involves creating an outline to guide your arguments about a topic and planning your ideas to convince the reader of your feelings about a difficult issue. If you still need assistance putting together your thoughts in composing a good paper, you have come to the right place. We have provided a series of steps and tips to show how you can achieve success in writing. This guide will tell you how to write an ethics paper using ethical essay examples to understand every step it takes to be proficient. In case you don’t have time for writing, get in touch with our professional essay writers for hire . Our experts work hard to supply students with excellent essays.

What Is an Ethics Essay?

An ethics essay uses moral theories to build arguments on an issue. You describe a controversial problem and examine it to determine how it affects individuals or society. Ethics papers analyze arguments on both sides of a possible dilemma, focusing on right and wrong. The analysis gained can be used to solve real-life cases. Before embarking on writing an ethical essay, keep in mind that most individuals follow moral principles. From a social context perspective, these rules define how a human behaves or acts towards another. Therefore, your theme essay on ethics needs to demonstrate how a person feels about these moral principles. More specifically, your task is to show how significant that issue is and discuss if you value or discredit it.

Purpose of an Essay on Ethics

The primary purpose of an ethics essay is to initiate an argument on a moral issue using reasoning and critical evidence. Instead of providing general information about a problem, you present solid arguments about how you view the moral concern and how it affects you or society. When writing an ethical paper, you demonstrate philosophical competence, using appropriate moral perspectives and principles.

Things to Write an Essay About Ethics On

Before you start to write ethics essays, consider a topic you can easily address. In most cases, an ethical issues essay analyzes right and wrong. This includes discussing ethics and morals and how they contribute to the right behaviors. You can also talk about work ethic, code of conduct, and how employees promote or disregard the need for change. However, you can explore other areas by asking yourself what ethics mean to you. Think about how a recent game you watched with friends started a controversial argument. Or maybe a newspaper that highlighted a story you felt was misunderstood or blown out of proportion. This way, you can come up with an excellent topic that resonates with your personal ethics and beliefs.

Ethics Paper Outline

Sometimes, you will be asked to submit an outline before writing an ethics paper. Creating an outline for an ethics paper is an essential step in creating a good essay. You can use it to arrange your points and supporting evidence before writing. It also helps organize your thoughts, enabling you to fill any gaps in your ideas. The outline for an essay should contain short and numbered sentences to cover the format and outline. Each section is structured to enable you to plan your work and include all sources in writing an ethics paper. An ethics essay outline is as follows:

- Background information

- Thesis statement

- Restate thesis statement

- Summarize key points

- Final thoughts on the topic

Using this outline will improve clarity and focus throughout your writing process.

Ethical Essay Structure

Ethics essays are similar to other essays based on their format, outline, and structure. An ethical essay should have a well-defined introduction, body, and conclusion section as its structure. When planning your ideas, make sure that the introduction and conclusion are around 20 percent of the paper, leaving the rest to the body. We will take a detailed look at what each part entails and give examples that are going to help you understand them better. Refer to our essay structure examples to find a fitting way of organizing your writing.

Ethics Paper Introduction

An ethics essay introduction gives a synopsis of your main argument. One step on how to write an introduction for an ethics paper is telling about the topic and describing its background information. This paragraph should be brief and straight to the point. It informs readers what your position is on that issue. Start with an essay hook to generate interest from your audience. It can be a question you will address or a misunderstanding that leads up to your main argument. You can also add more perspectives to be discussed; this will inform readers on what to expect in the paper.

Ethics Essay Introduction Example

You can find many ethics essay introduction examples on the internet. In this guide, we have written an excellent extract to demonstrate how it should be structured. As you read, examine how it begins with a hook and then provides background information on an issue.

Imagine living in a world where people only lie, and honesty is becoming a scarce commodity. Indeed, modern society is facing this reality as truth and deception can no longer be separated. Technology has facilitated a quick transmission of voluminous information, whereas it's hard separating facts from opinions.

In this example, the first sentence of the introduction makes a claim or uses a question to hook the reader.

Ethics Essay Thesis Statement

An ethics paper must contain a thesis statement in the first paragraph. Learning how to write a thesis statement for an ethics paper is necessary as readers often look at it to gauge whether the essay is worth their time.

When you deviate away from the thesis, your whole paper loses meaning. In ethics essays, your thesis statement is a roadmap in writing, stressing your position on the problem and giving reasons for taking that stance. It should focus on a specific element of the issue being discussed. When writing a thesis statement, ensure that you can easily make arguments for or against its stance.

Ethical Paper Thesis Example

Look at this example of an ethics paper thesis statement and examine how well it has been written to state a position and provide reasons for doing so:

The moral implications of dishonesty are far-reaching as they undermine trust, integrity, and other foundations of society, damaging personal and professional relationships.

The above thesis statement example is clear and concise, indicating that this paper will highlight the effects of dishonesty in society. Moreover, it focuses on aspects of personal and professional relationships.

Ethics Essay Body

The body section is the heart of an ethics paper as it presents the author's main points. In an ethical essay, each body paragraph has several elements that should explain your main idea. These include:

- A topic sentence that is precise and reiterates your stance on the issue.

- Evidence supporting it.

- Examples that illustrate your argument.

- A thorough analysis showing how the evidence and examples relate to that issue.

- A transition sentence that connects one paragraph to another with the help of essay transitions .

When you write an ethics essay, adding relevant examples strengthens your main point and makes it easy for others to understand and comprehend your argument.

Body Paragraph for Ethics Paper Example

A good body paragraph must have a well-defined topic sentence that makes a claim and includes evidence and examples to support it. Look at part of an example of ethics essay body paragraph below and see how its idea has been developed:

Honesty is an essential component of professional integrity. In many fields, trust and credibility are crucial for professionals to build relationships and success. For example, a doctor who is dishonest about a potential side effect of a medication is not only acting unethically but also putting the health and well-being of their patients at risk. Similarly, a dishonest businessman could achieve short-term benefits but will lose their client’s trust.

Ethics Essay Conclusion

A concluding paragraph shares the summary and overview of the author's main arguments. Many students need clarification on what should be included in the essay conclusion and how best to get a reader's attention. When writing an ethics paper conclusion, consider the following:

- Restate the thesis statement to emphasize your position.

- Summarize its main points and evidence.

- Final thoughts on the issue and any other considerations.

You can also reflect on the topic or acknowledge any possible challenges or questions that have not been answered. A closing statement should present a call to action on the problem based on your position.

Sample Ethics Paper Conclusion

The conclusion paragraph restates the thesis statement and summarizes the arguments presented in that paper. The sample conclusion for an ethical essay example below demonstrates how you should write a concluding statement.

In conclusion, the implications of dishonesty and the importance of honesty in our lives cannot be overstated. Honesty builds solid relationships, effective communication, and better decision-making. This essay has explored how dishonesty impacts people and that we should value honesty. We hope this essay will help readers assess their behavior and work towards being more honest in their lives.

In the above extract, the writer gives final thoughts on the topic, urging readers to adopt honest behavior.

How to Write an Ethics Paper?

As you learn how to write an ethics essay, it is not advised to immediately choose a topic and begin writing. When you follow this method, you will get stuck or fail to present concrete ideas. A good writer understands the importance of planning. As a fact, you should organize your work and ensure it captures key elements that shed more light on your arguments. Hence, following the essay structure and creating an outline to guide your writing process is the best approach. In the following segment, we have highlighted step-by-step techniques on how to write a good ethics paper.

1. Pick a Topic

Before writing ethical papers, brainstorm to find ideal topics that can be easily debated. For starters, make a list, then select a title that presents a moral issue that may be explained and addressed from opposing sides. Make sure you choose one that interests you. Here are a few ideas to help you search for topics:

- Review current trends affecting people.

- Think about your personal experiences.

- Study different moral theories and principles.

- Examine classical moral dilemmas.

Once you find a suitable topic and are ready, start to write your ethics essay, conduct preliminary research, and ascertain that there are enough sources to support it.

2. Conduct In-Depth Research

Once you choose a topic for your essay, the next step is gathering sufficient information about it. Conducting in-depth research entails looking through scholarly journals to find credible material. Ensure you note down all sources you found helpful to assist you on how to write your ethics paper. Use the following steps to help you conduct your research:

- Clearly state and define a problem you want to discuss.

- This will guide your research process.

- Develop keywords that match the topic.

- Begin searching from a wide perspective. This will allow you to collect more information, then narrow it down by using the identified words above.

3. Develop an Ethics Essay Outline

An outline will ease up your writing process when developing an ethic essay. As you develop a paper on ethics, jot down factual ideas that will build your paragraphs for each section. Include the following steps in your process:

- Review the topic and information gathered to write a thesis statement.

- Identify the main arguments you want to discuss and include their evidence.

- Group them into sections, each presenting a new idea that supports the thesis.

- Write an outline.

- Review and refine it.

Examples can also be included to support your main arguments. The structure should be sequential, coherent, and with a good flow from beginning to end. When you follow all steps, you can create an engaging and organized outline that will help you write a good essay.

4. Write an Ethics Essay

Once you have selected a topic, conducted research, and outlined your main points, you can begin writing an essay . Ensure you adhere to the ethics paper format you have chosen. Start an ethics paper with an overview of your topic to capture the readers' attention. Build upon your paper by avoiding ambiguous arguments and using the outline to help you write your essay on ethics. Finish the introduction paragraph with a thesis statement that explains your main position. Expand on your thesis statement in all essay paragraphs. Each paragraph should start with a topic sentence and provide evidence plus an example to solidify your argument, strengthen the main point, and let readers see the reasoning behind your stance. Finally, conclude the essay by restating your thesis statement and summarizing all key ideas. Your conclusion should engage the reader, posing questions or urging them to reflect on the issue and how it will impact them.

5. Proofread Your Ethics Essay

Proofreading your essay is the last step as you countercheck any grammatical or structural errors in your essay. When writing your ethic paper, typical mistakes you could encounter include the following:

- Spelling errors: e.g., there, they’re, their.

- Homophone words: such as new vs. knew.

- Inconsistencies: like mixing British and American words, e.g., color vs. color.

- Formatting issues: e.g., double spacing, different font types.

While proofreading your ethical issue essay, read it aloud to detect lexical errors or ambiguous phrases that distort its meaning. Verify your information and ensure it is relevant and up-to-date. You can ask your fellow student to read the essay and give feedback on its structure and quality.

Ethics Essay Examples

Writing an essay is challenging without the right steps. There are so many ethics paper examples on the internet, however, we have provided a list of free ethics essay examples below that are well-structured and have a solid argument to help you write your paper. Click on them and see how each writing step has been integrated. Ethics essay example 1

Ethics essay example 2

Ethics essay example 3

Ethics essay example 4

College ethics essay example 5

Ethics Essay Writing Tips

When writing papers on ethics, here are several tips to help you complete an excellent essay:

- Choose a narrow topic and avoid broad subjects, as it is easy to cover the topic in detail.

- Ensure you have background information. A good understanding of a topic can make it easy to apply all necessary moral theories and principles in writing your paper.

- State your position clearly. It is important to be sure about your stance as it will allow you to draft your arguments accordingly.

- When writing ethics essays, be mindful of your audience. Provide arguments that they can understand.

- Integrate solid examples into your essay. Morality can be hard to understand; therefore, using them will help a reader grasp these concepts.

Bottom Line on Writing an Ethics Paper

Creating this essay is a common exercise in academics that allows students to build critical skills. When you begin writing, state your stance on an issue and provide arguments to support your position. This guide gives information on how to write an ethics essay as well as examples of ethics papers. Remember to follow these points in your writing:

- Create an outline highlighting your main points.

- Write an effective introduction and provide background information on an issue.

- Include a thesis statement.

- Develop concrete arguments and their counterarguments, and use examples.

- Sum up all your key points in your conclusion and restate your thesis statement.

Contact our academic writing platform and have your challenge solved. Here, you can order essays and papers on any topic and enjoy top quality.

Daniel Howard is an Essay Writing guru. He helps students create essays that will strike a chord with the readers.