Equality or Equity?

- Posted December 2, 2022

- By Jill Anderson

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Inequality and Education Gaps

- K-12 School Leadership

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

Subscribe to the Harvard EdCast.

Longtime educator Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade thinks schools have been focused on equality for too long and need to fundamentally rethink the way they do things. He says a focus on equality is not producing the results that schools really need — providing all students with a quality education. While visiting schools many years ago, he noticed educators used the terms "equality" and "equity" interchangeably. Then, he started tracking what that actually means. The data clearly demonstrates that aiming for equality doesn't work. What would schools look like if they were, instead, truly equitable places?

In this episode of the Harvard EdCast, Duncan-Andrade reimagines what education could look like in America if we dared to break free of the system that constrains it.

Jill Anderson: I'm Jill Anderson. This is The Harvard EdCast. Long time educator, Jeff Duncan-Andrade, was working with schools when he noticed people using the words equality and equity interchangeably. Those words don't mean the same thing. Everybody's talking about equity without really taking the time to understand what it means, he says. And even worse, he says American schools have been more focused on equality for decades, and data shows it's not working. He's calling for a fundamental rethink of education nationwide with a real focus on equity. I wondered what that means, and what that might even look like. But I wanted Jeff to first tell us a bit more about the difference between equality and equity.

Jill Anderson: What is the difference between equity and equality? Because it seems like a lot of us are confused.

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: Well, so the way that I talk about equity is that I use my own home. I have twin boys that are nine years old. On virtually every measure, they're as equal is two children can be. Right? And yet, one of them when he was much younger was constantly thirsty, and the other one was constantly hungry. If I give both of them a bottle of water, is that equal? The immediate reaction of some people is to shake their head no. Then I ask the person, I say, "Why do you say it's not equal?" And then they say, "Well, because you're not giving [inaudible 00:02:35], your son who's always hungry, what he needs." And I say, "Yeah, but that's not the question I'm asking you. I'm asking you if it's equal." And then they kind of course correct. And they're like, "Well, yeah, it's equal, but it's not fair."

What I follow up with there is to say, "Yeah. You're right." But if you look at the definition of equality, there's nothing in there about fairness. It's presumed. The problem is we're attempting to have an equal education system in the most radically unequal industrialized nation in the history of the world. So to design an equal education system is both to ignore present and historical data and real material conditions, and it basically virtually guarantees that the social reproduction of those same inequalities. And we're not even doing equal schools.

Equity, on the other hand, is about fairness. And so the definition of equity that I use is that in an equitable system, you get what you need when you need it. This requires schools to first really assess: What do the children and the families in the community that we serve actually need? So you can't carbon copy. You can't just say, "Well, this worked over here in this community, and they have a really similar demographic profile, so we'll just copy this over." You can't McDonald-ize it. Right? And that requires, one, a lot of institutional dexterity, which schools really don't have right now. It requires dexterity around resource allocation. And it requires a very different kind of questioning and wondering and thinking and teacher support and teacher development, which schools really don't have right now.

And that's why I said that if we were going to really pursue an equitable education system, it requires us to make a hard pivot. And I think the hard pivot begins first with the purpose question, which I don't hear us asking in this country. And the purpose question is: For what? Why do we take children by law from their families for 13 consecutive years, for seven hours a day? Why are we doing that? And because we don't reexamine the why, the purpose, then what we end up doing is effectively putting lipstick on the pig. Public schools are presumed good in this society. I want us to challenge that.

Jill Anderson: I was looking around and I read an interview with you from many years ago where you said, and I'm quoting, "We lack the public will to transform our public schools."

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: I do think we lack the public will, and it's particularly disconcerting to me right now because I felt like coming back from the pandemic that we had a real opportunity. I felt like the potential for the will was there. People were really willing to rethink a lot of stuff. And what happened was that window has largely closed and what happened was that schools really went back to business as usual, even though they were saying, "We can't go back to business as usual." If you go to schools today, they look exactly like they did before the pandemic, excepting that you'll see more masks, you'll see more hand sanitizer, and you'll see occasional group testing for COVID. That's it. Everything else looks literally identical, the design of the school day, the curriculum, the set up off the classrooms, totally blew the opportunity to do a fundamental rethink.

In order to do a real rethink, you have to have resources. And I think that one of the things that gets in our way is that people don't really know what happens in schools. And so their kid gets dropped off, they come home. How was your day? It was good. Continue on. Right? And so we really want to re-jigger this whole thing. So I think that, one, we have to raise the national consciousness about what is actually happening in schools, and raise the national consciousness and awareness about the fact that, one, schools are really not good for kids the way we've designed them. Our children are not well. I'm not talking about just vulnerable and wounded kids, poor and working class kids, kids of color. I'm talking about the national data set on youth wellness is deeply, deeply troubling. And it's reflected in our larger public health data outcome.

I mean, we are the least well of any of the industrialized nations, and it's not even close. And yet, we spend by some estimates 100 X as much on healthcare as the next closest industrialized nation, which actually makes some sense because: When do you need healthcare? When you're sick. We have a national crisis, public health crisis, that public health officials have been banging the drum about for quite a while. And it can be directly connected to the way in which we organize our school day, and the experiences of our children over those 13 years. You can only ride this ride for so long before slamming on your brakes doesn't prevent you from careening off the edge of the cliff. And if you really look at the data, and I'm talking about our economic data, I'm talking about our health data, I'm talking about our broader social data, it's really, really troubling. We're in trouble.

This sits right up there with the climate crisis. If we correct the climate and the ozone layer, that doesn't mean we're going to be well. So I think that we have to raise the national awareness and consciousness about the place we're in as a society. And then we have to follow that by saying that it doesn't have to be this way. This is a choice that we can make, and the good thing that may be different than the climate crisis is that we could literally course correct this in one generation. If you had a generation of children that experienced in the public school system for all those 13 years and all those hours, a singular focus on wellness, to me, that is the purpose of public schools in a pluralistic multiracial democracy, is a promise to every family that when you give us your child, when you come back at the end of the day, they will be more well for having spent time with us than when you dropped them off. That's it.

So you can teach reading, you can teach writing, you can teach math, you can teach science, you can do sports, you can do art, you can do dance, you can do all of those things. But the question is: For what? If it's the model that we've designed, which is to maintain social inequality without social unrest, and to create pathways into employment, then carry on. If the goal is a pluralistic multiracial democracy that is more equal and more equitable, then we have to rethink the role of public schools in growing a generation of young people that know that is the agenda of our society.

Jill Anderson: Do you think that the intent was never really to make anything better? Is it just a Band-Aid?

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: We have an allergy in this country to truth telling. And I think without real truth telling, then the consciousness won't emerge. And I think that there's a fear in the broader society that: If we change schools, if we really do what you're saying, Jeff, if we really change schools, what if it's worse? Better the devil you know, right? Again, this goes back to people don't really know what happens in schools. The fear is I don't want to experiment on kids. Right? And what people don't process in that statement is we're already experimenting on kids. And we have an incredible amount of data on how that experiment is going, and it is failing, flat out.

And it's not that things have been slow to change. Things are worse. We're headed in the wrong direction. The wealth gap in this society is far and away the biggest it's ever been. Health outcomes, wellness is far and away the worst it's ever been. The forms of inequality that we can track, even economists are freaking out. They are really concerned. So for me, the question is one: Why aren't people putting that picture together? Why aren't more leaders talking about that? I'm an imminently hopeful dude. I firmly believe we're going to figure this out. But I don't think that you can really close your eyes and pray your way out of this. I was looking for what's the kind of big, global gold standard data set for looking at this in nations, and what I stumbled upon is called the World Peace Index.

That is the global gold standard for measuring peace, democracy, economic stability and sustainability in 99.8 of the world's population. So I figured when I started looking at this in 2015, and this is used by the United Nations, UNESCO, by the World Health ... I mean, this is a widely accepted kind of mega index to look at how our nation's doing. And when I first looked at it, I figured we're top 20, some of the Nordic countries will probably outpace us. But in 2015, I think we were 94th.

Jill Anderson: Wow.

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: And my jaw dropped. I was like, "Whoa." Right? And then I kept tracking it every year, and every year since 2015, we have dropped and dropped and dropped. The '22 index just came out, and I think now we're 122nd in the world. That is such an indictment of the maintenance model that we're hanging onto, the devil that we know. And we're in a free fall. And I think schools are ... If we're going to do a fundamental rethink about schools, we have to really have a coming to truth, as South Africa did. We have to have a truth and reconciliation conversation about: Where are we? How did we get here? What sets of decisions did we make to get here? And then how are we going to course correct? Right? How are we going to raise a generation of young people that experience truth telling about what this society is? And then let's create school systems that are really developing young people that are problem solvers, whether it's for cancer, whether it's for the climate crisis, and schools are not that.

Schools are about compliance, internalize, regurgitate, repeat. That model at some level made some sense when we first started schools because schools were designed to create functional workers for factories. We're not that anymore. And I think that's why so many young people find school completely inane and obsolete.

Jill Anderson: Are there any schools that you would say are equitable today, are practicing that kind of model?

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: Whole schools, none that I've seen. I think some are more committed to it than others. There is incredible research and examples of spaces and places where it's happening inside of schools, so individual classrooms, or individual programs. But tip to finish, edge to edge, top to bottom, I have not seen it in a US school. That doesn't mean it doesn't exist. But I think that is one of the questions that we have to solve for. There has to be a major influx of resources to begin to create the space for schools to innovate, to begin to figure out. How do we stop moving deck chairs around on a Titanic and calling it different? And how do we start really thinking about remaking the ship? And schools are not given the runway or the resources to be innovative.

You saw that coming out of the pandemic. All these superintendents were like, "Yeah. You're giving me this crisis money right now, but I can't build anything long-term with this because you're going to take it away. And then I'm going to have to cut that, and the damage that does both to staffing and to the climate and culture of a community is bad." I'm immediately adjacent to Silicon Valley. And I've had the privilege of spending quite a bit of time with some of the leaders of some of the largest companies there. And to a person, when I'm in those conversations with them, one of the things that they have all said to me at some point or another is that one of our most valuable commodities as a corporation is failure. And I was like, "Huh?"

And then I started thinking about how in education. We duck, dodge, and deny failure like it is the worst thing ever. And the more I explored that with them, the more I understood just how different the consciousness, the climate, and the culture has to be for a space to be innovative, the goal isn't to fail, but the known is if we're going to push the envelope, if we're going to innovate, if we're going to try and really do things that are cutting edge and different, we're going to fail, and we're going to fail a lot. And the key is not that you start worrying about failure, but that you build an infrastructure around the failure, so that you're learning and you're growing.

What schools try to do is they try to do mega change, so the whole school's going to do X, Y, or Z. The whole district's going to do X, Y, or Z. And that consistently falls flat on its face because one, that's not how you do institutional change. The only way that you pull that off is with power. You just force people. But no one actually changes, they just comply. But if you want to change, you have to start with smaller units. You have to have good R and D. And you have to innovate and tweak constantly. You can't wait for a semester to get test scores back and decide if your literacy program needs improvement. You can't wait for a year. There's a whole lot of spaces and places that we could be learning from in education about how to make this move in a way that is actually creating transformation and change that's healthy, that's good for kids, that's good for teachers, that's good for families.

Jill Anderson: So in an equitable school model, do you think that it's just every school, every classroom, will really look different?

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: I think it depends on how you operationalize the term different. Every classroom you go into right now looks different. Whether you want to admit it or not, it is a different teacher, a different group of kids. So there's a way in which there's a cold comfort in the kind of fast food approach to schools, which is I'm going to go in and I'm going to see a teacher in front of the room, and I'm going to see desks organized. I'm going to see kids seated and calm. And I'm going to see important stuff on the walls, and kids are going to be raising their hand. And I think that we have to let go of that. The classrooms that I know where real learning is happening are on fire. And people are like, "Whoa, this is chaos."

But when you look at what actually comes out of that classroom, it's super investment. Kids are super excited. The teacher's super excited. And lots and lots of learning is happening. So part of the national consciousness has to change in giving people live look ins to: What are we actually talking about here? What should we expect to see when we walk in classrooms? What that looks like day to day and room A to room B, it needs to look a little bit different based on who's in there and what they're doing in the particular moment.

What I think shouldn't be different is the core values. So pedagogically, you're going to see some difference. Curriculum, you're going to see some difference. Interactions, you're going to see some difference. But when you kind of zoom out a little bit and you look at what are the core values that are happening right here, no, we've actually known this again for 40 years from the research. The most effective teachers across four decades of research pretty much do the same things. And no matter what the political climate of the day is, or what the sexy curriculum or assessment is, they are doing pretty much the same things. What we've been calling the kind of new three Rs, but they're not new, they're the old three Rs, that is widely supported by the research not just in education, but across all those fields about what actually creates wellbeing and investment from children.

First and foremost, it's relationships. Right? So if you walked into classroom A or classroom B, what you would see is deep, caring relationships between the adult and the children, and between the children and the children. The second thing is relevance. You walk into the space and you would see kids on fire about learning because they actually care about what they're learning. Right? It's relevant to their life. It's relevant to their history. It's relevant to their language. It's relevant to their community. If you went space to space, that might look a little different because what's relevant to group A might be a little different than what's relevant to group B. But you could still hit all the state and national standards with a modified curriculum.

And then the third thing is the space would reflect responsibility, a responsibility to themselves, a responsibility to the school, a responsibility to the community, a responsibility to the nation, a responsibility to the world. Part of that responsibility would be that if a child is wounded, that we don't punt. We don't send them away. We don't make them somebody else's problem. The classroom community would be responding and understanding that is education. Learning your responsibility to your brother or your sister that's sitting next to you, and saying that we can teach all the standards we need to teach with a focus on wellness and care. That's not going to stop you from reading.

In fact, that's actually going to increase reading. But what happens right now is because we're trying to develop, we're trying to sanitize classrooms, so it's like, "Don't bring any of that in here." What you end up, people think they want to see is they want to see flat compliance. Nobody is hurting. Nobody is sad. Nobody is laughing out loud. None of the human emotions are allowed in the classroom. We don't even let kids talk to each other. That's seen as disruption.

Jill Anderson: If we have some educators listening, what can they actually do?

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: Start a pilot. Start a pilot project, one classroom. You're a parent, just figure out. How can that classroom where your child is going to school every day be more equitable? My sons are in fourth grade. Oftentimes when I go in, I'm not particularly focused on them because I know where they're at. I'm looking at some of the other kids that are sitting next to them that I know based on my conversations with them, and based on my time being invested in the kids that are moving along the grades with them, I know the kids that need a breakfast bar. And so I'm coming with that to begin to develop a relationship with them around: How do I start getting you loving reading as much as my sons love reading?

People will be surprised at how micro investments can create institutional cultural transformation because if you really think about it, if you change one kid's experience on one day, you've changed the institution. Schools have become consumed wrongly with not only big data, but the wrong big data. And that then leads us to think about change at the wrong scale. For a teacher, or for a school leader, seriously, just start a pilot project, one unit, one classroom, one group of teachers that say, "Hey, we really want to do something fundamentally different." And give them the runway and the bandwidth to innovate and learn with the expectation, this is the expectation that I always have when I go in and work with schools, is that we're going to start with the coalition of the willing. So if you're not down for this right now, it's cool. Right?

But if you are, then we're going to invest and work with you, that small group. But the expectation is that you become a teacher of teachers. So you're not going to get all this runway to be really innovative and then you're off and running and goodbye. There's going to be a phase two, and I often work in three year phases because that's about how much time it takes for you to really start seeing cultural transformation. It doesn't happen overnight, it takes a real investment of time and energy. And then at the end of that phase one, that third year, then those teachers that I work with, they go get five more teachers. And that becomes meta project two, where now each of those five teachers that did the innovative process for the first three years, they now have satellite groups. And it's something about when a parent invites a parent, or a kid invites a kid, or a teacher invites a teacher, that warrants a very different entry point. Right?

And I think that's back to our earlier commentary about: How do we build the will? I think part of the way you build the way is the way you do the ask. And if it comes from power, the relationship to power in schools has historically been a negative one, so even when good ideas get shoved down from power, the idea wasn't bad, the implementation approach was flawed. Part of what we need to rethink, or part of what I would encourage the audience to rethink is the way in which you approach innovation and just the invitation to doing it, and a commitment to learning, an arc of growth, and understanding that at the end of year one, at the end of year two, at the end of year three, at the end of year 30, it's still going to be messy. But what we have got to change in our consciousness is this desire to sanitize the classroom, and embracing that meaningful education is messy. The meaning is in the mess. And if you resent the mess, you will miss the meaning.

Jill Anderson: Thank you so much, Jeff. Lots and lots of stuff to think about from this conversation today.

Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade: Thank you for making some time to allow me to run my mouth.

Jill Anderson: Jeff Duncan-Andrade is a professor of Latina and Latino studies and race and resistance studies at the San Francisco State University. He's the author of Equality or Equity: Toward a Model of Community-Responsive Education . I'm Jill Anderson. This is The Harvard EdCast, produced by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Navigating Book Bans

A guide for educators as efforts intensify to censor books

Creating Trans-Inclusive Schools

For Future Generations

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

Why Is Education So Important in The Quest for Equality?

Gerald Nelson | April 14, 2022 | Leave a Comment

Image: Pikist

Education is vital. We can all agree on this but where we fall out of the agreement is why exactly education is so necessary for equality. Without education, there can be no progress, no development, and no improvement.

In today’s world, we are ever more aware of the issues surrounding sexism, racism, and inequality, allowing for a greater understanding of the importance of educating people to avoid these biases occurring in the first place.

What is Educational Equality and why is it necessary?

Equality isn’t always so simple. Some may assume, for example, that educational equality is as simple as providing children with the same resources. In reality, however, there’s a lot more to it than this. We will check what governments are doing to achieve this goal. What actions they are taking to advance the cause of equality? Education is crucial because it’s a toolkit for success:

- With literacy and numeracy comes confidence, with which comes self-respect. And by having self-respect, you can respect others, their accomplishments, and their cultures.

- Education is the fundamental tool for achieving social, economic, and civil rights – something which all societies strive to achieve.

Educational Inequality is usually defined as the unequal distribution of educational resources among different groups in society. The situation becomes serious when it starts influencing how people live their lives. For example, children will be less likely to go to school if they are not healthy, or educated because other things are more urgent in their life.

Categorical Educational Inequality

Categorical Education Inequality is especially apparent when comparing minority/low-income schools with majority/high-income schools. Are better-off students systematically favored in getting ahead? There are three plausible conditions:

- Higher-income parents can spend more time and money on private tutoring, school trips, and home study materials to give their children better opportunities. Therefore, better-off students have an advantage due to access to better schools, computers, technology, etc. (the so-called opportunity gap).

- Low-income schools lack the resources to educate their students. Therefore their students tend to have worse educational outcomes.

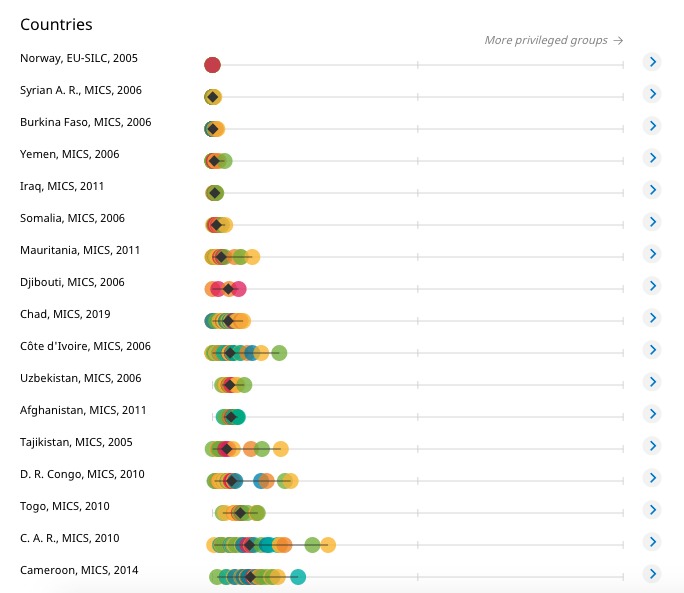

- Although the public school system is a government-funded program to allow all students an equal chance at a good education, this is not the case for most schools across third world countries – see UNESCO statistics below:

How Educational Inequality is fueling global issues

Educational inequality is a major global crisis. It has played a role in economic problems, amplified the political deadlock, exacerbated the environmental predicament, and threatens to worsen the human rights crisis. If equality in education is not addressed directly, these crises will only deepen because:

- Educational Inequality is also about race and gender . Those who are less privileged are condemned to poverty and unemployment because of a lack of quality educational resources.

- Without a sound education, people have less knowledge of the world around them or the issues facing their communities. They are less likely to vote or to pay attention to politics. This leaves them vulnerable to manipulation by those who represent narrow interests and promote fear, hatred, and violence. The result is an erosion of democratic values and an increase in authoritarianism.

- Without correction, human rights abuses will continue due to a lack of legal representation among those with no or low education levels.

- Poverty, unemployment, crimes, and health issues: A lack of education and skills forces children into poverty because they can’t get jobs or start a business. It also leaves them without hope and is one of the reasons for unemployment, lower life expectancy, malnutrition, a higher chance of chronic diseases, and crime rates.

- Limited opportunities: The most significant issue is that lack of education reduces the opportunities for people to have a decent life. Limited options increase the division of social classes, lower social mobility, and reduce the ability to build networks and social contacts. Students in poor countries also spend a lot of time working to support their families rather than focusing on their school work. These factors also worsen the upbringing of coming generations.

- Extremism: Inequality can also lead to increased violence, racism, gender bias, and extremism, which causes further economic and democratic challenges.

- Inability to survive pandemics: Unlike developed nations after COVID, underdeveloped countries are stuck in their unstable economic cycles. Inequality causes a lack of awareness and online educational resources, lower acceptance of preventive measures, and unaffordable vaccines, for example. According to the United Nations , “Before the coronavirus crisis, projections showed that more than 200 million children would be out of school , and only 60 percent of young people would be completing upper secondary education in 2030”.

- Unawareness of technological advancements: The world is becoming more tech-savvy, while students in underdeveloped countries remain unaware of the latest technological achievements as well as unable to implement them. This also widens the education gap between countries.

- Gender inequality in education: In general, developing countries compromise over funds allocation for women’s education to manage their depletion of national income. As such, they consider women less efficient and productive than men. Meanwhile, many parents do not prefer sending their daughters to school because they do not think that women can contribute equally to men in the country’s development. However, if we have to overcome this, there should be an increase in funding and scholarships for women’s education.

- Environmental crises: People are usually less aware of the harmful emissions produced in their surroundings and are therefore less prepared to deal with increased pollution levels. This also affects climate change. The less educated the children, the more likely they are to contribute to climate change as adults. This is because education is not just about learning facts and skills but also about recognizing problems and applying knowledge in innovative ways.

- A child who has dropped out of school will generally contribute less to society than a child who has completed secondary school. A child who has completed secondary school will contribute less than a child who went to university. This difference increases over time because those with higher levels of education tend to be more open-minded, flexible thinkers and are therefore better able to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Equality in education is therefore essential for addressing international issues including economic inequality, climate change, social deprivation, and access to healthcare. Many children in poor regions are deprived of education (see chart below) which is the only way out of poverty .

Proposed Solutions

The United Nations Development Program says that access to education is a human right, and should be individually accessible and available to all by 2030. It demands:

- International collaborations to ensure that every child has the same quality education and to develop joint curricula and academic programs. The quality of teaching methodologies should not be compromised and includes providing financial assistance and tools for equal access.

- Running campaigns to discourage race, gender, and ethnicity differences, arranging more seminars to reach low-income groups, and providing adequate financial assistance, training, and part-time jobs for sole earners.

- Modifying scholarship criteria to better support deserving students who cannot afford university due to language tests and low grades.

- Increasing the minimum wage so that sole breadwinners can afford quality education for their children.

- Schools should bear transportation costs and offer free grants to deserving kids from low-income families.

- Giving more attention to slum-side schools by updating and implementing new techniques and resources.

- Allowing students to learn in their own language with no enforcement of international languages and offering part-time courses in academies and community colleges in other languages.

Resolving educational inequality has many benefits for the wider society. Allowing children from disadvantaged backgrounds to get an education will help them find better jobs with higher salaries, improving their quality of life, and making them more productive members of society. It decreases the likelihood of conflict and increases access to health care, stable economic growth, and unlimited opportunities.

Conclusion:

It’s been said that great minds start out as small ones. To level the playing field, we need to focus on best educating our next generation of innovators and leaders, both from an individual and a societal standpoint. If we want equality to become a reality, it will be up to us to ensure that equality is at the forefront of our education system.

References:

Environmental Conscience: 42 Causes, Effects & Solutions for a Lack of Education – E&C (environmental-conscience.com)

School of Education Online Programs: What the U.S. Education System Needs to Reduce Inequality | American University

Educational Inequality: Solutions | Educational Inequality (wordpress.com)

Giving Compass: Seven Solutions for Education Inequality · Giving Compass

Science.org: Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline

Research Gate: Inequality and Economic Growth

University of Munich: pdf (uni-muenchen.de)

Research Gate: Effects-of-inequality-and-poverty-vs-teachers-and-schooling-on-Americas-youth.pdf (researchgate.net)

Borgen Magzine

United Nations: Education as the Pathway towards Gender Equality

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals – Education

This article has been edited in line with our guidelines

Gerald Nelson is a freelance academic essay writer at perfectessaywriting.com who also works with several e ducational and human rights organizations.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to [email protected]

Educational Equality for All Students Essay

Introduction, bank’s four approaches, color-blindness, racism, and instructional strategies, a program for integrating multiculturalism, incorporating positive behavior in schools: techniques.

Nowadays, multiculturalism is one of the essentialities of the modern education due to the rise in the diversity in the classroom (Ford, 2014). In turn, this concept is highlighted in K-12 standards by referring to culturally responsive teaching, justice in decision-making and racial awareness and identity (Aceves & Orosco, 2014).

In spite of the gravity of multiculturalism in the American society, the teachers and students tend to misinterpret the concept of the intercultural environment by often regarding representatives of various ethnicities as “monocultural” (Ford, 2014, p. 60). This misconception drives the development of stereotypes and bullying and contributes to the fact that modern American education lacks consistency (Ford, 2014). These issues and the rising significance of multiculturalism are the primary reasons for conducting research in this sphere.

Consequently, in the context of this paper, evaluating Bank’s four approaches to integration of multiculturalism and the color-blindness tactic are vital. Alternatively, offering instructional strategies to minimize the occurrence of racism in the classroom and designing a program to make multiculturalism an essential part of the educational process are critical. In the end, modifying school-wide behavior, making it more culturally responsive, and proposing suitable techniques to achieve these goals cannot be underestimated, as they improve the level of multiculturalism in the educational institution.

In the first place, evaluating and analyzing Bank’s approaches to the incorporation of the multicultural content into the curriculum is critical. In this case, the researcher divided the tactics into contributive, additive, transformative, and social action approaches (Chun & Evans, 2016). In this case, a contributive approach is often referred to as the most common strategy to cultivate an increase in the level of multiculturalism in the classroom.

It is commonly associated with using holidays and historical figures to build an understanding of international relations in the world (Chun & Evans, 2016). In the context of the curriculum, organizing various events such as international food festival and devoting each week to different leaders such as Martin Luther King and Christopher Columbus will help determine a contribution of various ethnicities to the development of the United States of America.

In turn, the additive approach implies emphasizing the importance of diversity without redesigning the curriculum (Chun & Evans, 2016). In this case, the instructor uses the common historical facts and well-developed programs without spending additional time on changing the content (Chun & Evans, 2016). Referring to historical events, periods, and ethnicities such as indigenous people, Hispanics, and African Americans during the educational sessions will help form a general overview of the history of the country and the world. Organizing these classes every month is the most appropriate timeframe.

In turn, one cannot underrate the effectiveness of the transformative approach, as it allows for discovering historical events from dissimilar angles (Chun & Evans, 2016). In the context of the curriculum, the proposed above educational sessions about the fundamental historical events and figures can be modified by adding different perspectives. For example, while discussing the African-American Civil Rights movements, the instructor has to refer to the viewpoints of various continents like the Americas and Europe and races such as African Americans and Hispanics. Each class can be divided into segments to devote equal time to each discussion.

As for the social action theory, it implies that students discuss the issue and participate in finding a solution (Chun & Evans, 2016). In the first place, this strategy can be applied to the curriculum with the help of discussion forums. This concept will assist in cultivating an understanding of the gravity of the issue of sexism or racism in the classroom. After indicating a problem, the students will be encouraged to develop various solutions to minimize the level of racism in American society.

The concept of color-blindness suggests that the individuals have to be treated equally disregarding their visual racial attributes (Mazzocco, 2015). This approach does not categorize the modern society into ethnic groups and highlights the importance of individualism (Mazzocco, 2015). Nonetheless, despite the beneficial intentions of color-blindness, this approach cannot solely diminish the racism. On the contrary, some scholars refer to the fact that it contributes to its development.

For example, color-blindness does not help the students to adapt to the habits of representatives of different cultures during the social interactions (Apfelbaum, Norton, & Sommers, 2012). Simultaneously, it creates racial bias and bullying, as the students are not educated about the cultural features and differences (Apfelbaum et al., 2012). Instantaneously, color-blindness diminishes the significance of discrimination in modern society and disregards the rights of various ethnicities (Apfelbaum et al., 2012). A combination of these factors underlines that color-blindness is a primary source of racism due to misunderstandings and the lack of social background and flexibility.

To avoid racism and discrimination in the classroom, the teacher can utilize various external resources such as YouTube. Following this approach will help provide an objective opinion about races and cultural differences, and the teacher’s tone will be unbiased. Simultaneously, the instructor can develop a set of rules, which all students have to follow. Alternatively, students can participate in the development and propose their own solutions to enhance the atmosphere and learning environment in the class. Applying this tactic can assist in avoiding discrimination, as this framework has to be equally respected by all participants of the educational process.

Speaking of other instructional tactics, they have to comply with the K-12 principles of cultural responsiveness and engage different students into the discussions (Aceves & Orosco, 2014). In this case, emphasizing the significance of equality together with the students will assist in building a learner-friendly environment in the classroom.

At the same time, students’ participation in various discussions concerning race and culture will help them express their opinions and shape the understanding of the diversity and its gravity. It could be said that the tactics mentioned above will help minimize the gaps created by the color-blindness and racial bias. It will be one of the approaches to encourage students’ participation and underline the importance of diversity.

Based on the analysis conducted above, it is critical to design an educational program, which will support the integration of multiculturalism in the curriculum. In this case, the importance of multiculturalism can be delivered to the students by organizing various discussions, performances, and cultural evenings monthly or weekly. Applying the game-based learning is reasonable, as it is believed to have a positive impact on the academic excellence (Yien, Hung, Hwang, & Lin, 2014). Dressing up and playing the roles of the representatives of different cultures will help students to feel the diversity of the cultural world.

As for the literature classes, this subject can apply the general concepts of the program. Once a week a teacher can identify the culture-related fictional literature to be read during the class. The readings can be represented in the form of short stories or tales. After reading the materials, the students can discuss the actions of the main characters and compare them with the customs of their own cultures. Using this approach will assist in learning about the diversity and multicultural nature of the modern world. In turn, learning and being acquitted with the poems of different cultures could serve as a basis for the development of performances and cultural evenings once a week.

As for the history, this subject can apply similar concepts as literature due to the interdependence and similarities of these disciplines. Nonetheless, in this case, it will be critical to discuss the connection between the cultures and their contribution to the development of the world. Displaying dissimilar opinions with the help of the transformative approach will have a beneficial impact on the student’s understanding of multiculturalism. At the same time, using performances of famous historical events and games make the classes interesting and interactive.

In this case, the discussions can be organized once a week while other occasions can be held once a month. Furthermore, integrating history and literature can be viewed as a possibility. As for math, the teacher can design the tasks to be associated with the customs and traditions of different cultures. Simultaneously, conducting historical sessions about math once a week will help students become acquainted with diversity, and using technology will make lectures more interactive (to be organized twice a week).

Focusing on the educational sphere is critical, as it is one of the definers of the educational quality. Nonetheless, one cannot underestimate the gravity of the school-wide behavior on cultivating the responsive cultural environment within the educational unit. In the first place, one of the primary goals is to support multiculturalism in the educational institution.

In this case, this goal can be reached by encouraging students to participate in various events ( School climate and discipline , 2016). Consequently, it could be said that organizing school-wide events such as international food and culture evening, dances, and cultural conferences will assist students and teachers in sharing their understating of multiculturalism.

Another aspect, which will have a positive impact on the development of multiculturalism is paying vehement attention to the emotional intelligence and learning environment ( School climate and discipline , 2016). These factors can be delivered to the students with the assistance of supporting activities such as educational sessions and counseling.

In this instance, these activities will have a beneficial impact on students and teachers simultaneously. The students can clearly express their problems to the counselors and receive feedback. At the same time, critical attention will be paid to teachers’ emotional intelligence and their ability to deliver the ideas of multiculturalism to students. Based on the evaluation of the instructor’s intelligence, it will be evident if the additional training is a requirement.

Lastly, one cannot underestimate the involvement of parents’ in the educational process ( School climate and discipline , 2016). They are critical definers of the academic excellence, and their support and awareness of the essentiality of diversity and multiculturalism have a positive impact on the school-wide practices. In this case, encouraging parents to participate in the specialized educational sessions will have a positive influence on the learning conditions at home and inside the institution. At the same time, the parents can take part in the cultural evenings and events and schedule meetings with the counselor to resolve the problems in case of their occurrence.

Aceves, T., & Orosco, M. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching.

Apfelbaum, E., Norton, M., & Sommers, S. (2012). Racial color-blindness: Emergence, practice, and implications. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21 (3), 205-209.

Chun, E., & Evans, A. (2016). Rethinking cultural competence in higher education: An ecological framework for student development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ford, D. (2014). Why education must be multicultural: Addressing a few misconceptions with counterarguments. Gifted Child Today, 37 (1), 59-62.

Mazzocco, P. (2015). Talking productively about the race in colorblind era . Web.

School climate and discipline: Key elements of school-wide preventive and positive discipline policies. (2016).

Yien, J., Hung, C., Hwang, G., & Lin, Y. (2014). A game-based learning approach to improving students’ learning achievements in a nutrition course. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10 (2), 1-10.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, April 3). Educational Equality for All Students. https://ivypanda.com/essays/educational-equality-for-all-students/

"Educational Equality for All Students." IvyPanda , 3 Apr. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/educational-equality-for-all-students/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Educational Equality for All Students'. 3 April.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Educational Equality for All Students." April 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/educational-equality-for-all-students/.

1. IvyPanda . "Educational Equality for All Students." April 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/educational-equality-for-all-students/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Educational Equality for All Students." April 3, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/educational-equality-for-all-students/.

- Colorblindness as a Reason for Workplace Discrimination

- Racial Relations and Color Blindness

- Racial Discrimination and Justice in Education

- Dealing With Race Discrimination: Impact of Color Blindness

- Race at the Intersections: Sociology, 3rd Wave Feminism, and Critical Race Theory

- White Supremacy in "White Like Me" by Tim Wise

- Ferguson Unrest's Causes and Response

- Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real About Race in School

- Ethnicity Problem in the USA

- Racial Discrimination in High Education

- Needs Assessment and Instructional Design Process

- Gender Issues in the School Environment

- Educational Environment: Diversity Problems Management

- Australian Classroom Diversity Issues

- Barriers to Educational Change

Your Right to Equality in Education

Getting an education isn’t just about books and grades – we’re also learning how to participate fully in the life of this nation. (We’re tomorrow’s leaders after all!)

But in order to really participate, we need to know our rights – otherwise we may lose them. The highest law in our land is the U.S. Constitution, which has some amendments, known as the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights guarantees that the government can never deprive people in the U.S. of certain fundamental rights including the right to freedom of religion and to free speech and the due process of law. Many federal and state laws give us additional rights, too.

The Bill of Rights applies to young people as well as adults. And what I’m going to do right here is tell you about EQUAL TREATMENT .

DO ALL KIDS HAVE THE RIGHT TO AN EQUAL EDUCATION?

Yes! All kids living in the United States have the right to a free public education. And the Constitution requires that all kids be given equal educational opportunity no matter what their race, ethnic background, religion, or sex, or whether they are rich or poor, citizen or non-citizen. Even if you are in this country illegally, you have the right to go to public school. The ACLU is fighting hard to make sure this right isn’t taken away.

In addition to this constitutional guarantee of an equal education, many federal, state and local laws also protect students against discrimination in education based on sexual orientation or disability, including pregnancy and HIV status.

In fact, even though some kids may complain about having to go to school, the right to an equal educational opportunity is one of the most valuable rights you have. The Supreme Court said this in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case when it struck down race segregation in the public schools.

If you believe you or someone you know is being discriminated against in school, speak up! Talk to a teacher, the principal, the head of a community organization or a lawyer so they can investigate the situation and help you take legal action if necessary.

ARE TRACKING SYSTEMS LEGAL?

Yes, as long as they really do separate students on the basis of learning ability and as long as they give students the same basic education.

Many studies show, however, that the standards and tests school officials use in deciding on track placements are often based on racial and class prejudices and stereotypes instead of on real ability and learning potential. That means it’s often the white, middle-class kids who end up in the college prep classes, while poor and non-white students, and kids whose first language isn’t English, end up on “slow” tracks and in vocational-training classes. And often, the lower the track you’re on, the less you’re expected to learn – and the less you’re taught.

Even if you have low grades or nobody in your family ever went to college, if you want to go to college, you should demand the type of education you need to realize your dreams. And your guidance counselor should help you get it! Your local ACLU can tell you the details of how to go about challenging your track placement.

CAN STUDENTS BE TREATED DIFFERENTLY IN PUBLIC SCHOOL BASED ON THEIR SEX?

Almost never. Public schools may not have academic courses that are just for boys – like shop – or just for girls – like home economics. Both the Constitution and federal law require that boys and girls also be provided with equal athletic opportunities. Many courts have held, however, that separate teams for boys and girls are allowed as long as the school provides students of both sexes the chance to participate in the particular sport. Some courts have also held that boys and girls may always be separated in contact sports. The law is different in different states; you can call your local ACLU affiliate for information.

CAN GIRLS BE KICKED OUT OF SCHOOL IF THEY GET PREGNANT?

No. Federal law prohibits schools from discriminating against pregnant students or students who are married or have children. So, if you are pregnant, school officials can’t keep you from attending classes, graduation ceremonies, extracurricular activities or any other school activity except maybe a strenuous sport. Some schools have special classes for pregnant girls, but they cannot make you attend these if you would prefer to be in your regular classes.

CAN SCHOOLS DISCRIMINATE AGAINST GAY STUDENTS?

School officials shouldn’t be able to violate your rights just because they don’t like your sexual orientation. However, even though a few states and cities have passed laws against sexual orientation discrimination, public high schools have been slow to establish their own anti-bias codes – and they’re slow to respond to incidents of harassment and discrimination. So while in theory, you can take a same-sex date to the prom, join or help form a gay group at school or write an article about lesbian/gay issues for the school paper, in practice gay students often have to fight hard to have their rights respected.

WHAT ABOUT STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES?

Although students with disabilities may not be capable of having exactly the same educational experiences as other students, federal law requires that they be provided with an education that is appropriate for them. What is an appropriate education must be worked out individually for each student. For example, a deaf student might be entitled to be provided with a sign language interpreter.

In addition to requiring that schools identify students with disabilities so that they can receive the special education they need in order to learn, federal law also provides procedures to make sure that students are not placed in special education classes when they are not disabled. If you believe you’re not receiving an appropriate education, either because you are not in special classes when you need to be, or because you are in special classes when you don’t need to be, call the ACLU!

And thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), students who are HIV positive have the same rights as every other student. People with HIV are protected against discrimination , not only in school but in many other public places such as stores, museums and hotels.

People with HIV aren’t a threat to anyone else’s health, because the AIDS virus can’t be spread through casual contact. That’s just a medical fact. Your local ACLU can provide information on how to fight discrimination against people with HIV.

CAN I GO TO PUBLIC SCHOOL IF I DON’T SPEAK ENGLISH?

Yes. It is the job of the public schools to teach you to speak English and to provide you with a good education in other subjects while you are learning. Students who do not speak English have the right to require the school district to provide them with bilingual education or English language instruction or both.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” –Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972

We spend a big part of our life in school, and our voices count. Join the student government! Attend school meetings! Petition your school administration! Talk about your rights with your friends! Let’s make a difference!

Produced by the ACLU Department of Public Education. 125 Broad Street, NY NY 10004. For more copies of this or any other Sybil Liberty paper, or to order the ACLU handbook The Rights of Students or other student-related publications, call 800-775-ACLU or visit us on the internet at https://www.aclu.org .

Related Issues

- Racial Justice

- Mass Incarceration

- Smart Justice

- Women's Rights

Stay Informed

Every month, you'll receive regular roundups of the most important civil rights and civil liberties developments. Remember: a well-informed citizenry is the best defense against tyranny.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

Search the United Nations

- Independent side events

- FAQs - General

- FAQs - Logistics

- Vision Statement

- Consultations

- International Finance Facility for Education

- Gateways to Public Digital Learning

- Youth Engagement

- Youth Declaration

- Education in Crisis Situations

- Addressing the Learning Crisis

- Transform the World

- Digital Learning for All

- Advancing Gender Equality

- Financing Education

Why inclusive education is important for all students

Truly transformative education must be inclusive. The education we need in the 21st century should enable people of all genders, abilities, ethnicities, socioeconomic backgrounds and ages to develop the knowledge, skills and attitudes required for resilient and caring communities. In light of pandemics, climate crises, armed conflict and all challenges we face right now, transformative education that realizes every individual’s potential as part of society is critical to our health, sustainability, peace and happiness.

To achieve that vision, we need to take action at a systemic level. If we are to get to the heart of tackling inequity, we need change to our education systems as a whole, including formal, non-formal and informal education spaces .

I grew up in the UK in the 1990s under a piece of legislation called Section 28 . This law sought to “ prohibit the promotion of homosexuality ” and those behind it spoke a lot about the wellbeing of children. However, this law did an immense amount of harm, as bullying based on narrow stereotypes of what it meant to be a girl or a boy became commonplace and teachers were disempowered from intervening. Education materials lacked a diversity of gender representation for fear of censure, and as a result, children weren’t given opportunities to develop understanding or empathy for people of diverse genders and sexualities.

I have since found resonance with the term non-binary to describe my gender, but as an adolescent, what my peers saw was a disabled girl who did not fit the boxes of what was considered acceptable. Because of Section 28, any teacher’s attempts to intervene in the bullying were ineffective and, lacking any representation of others like me, I struggled to envisage my own future. Section 28 was repealed in late 2003; however, change in practice was slow, and I dropped out of formal education months later, struggling with my mental health.

For cisgender (somebody whose gender identity matches their gender assigned at birth) and heterosexual girls and boys, the lack of representation was limiting to their imaginations and created pressure to follow certain paths. For LGBTQ+ young people, Section 28 was systemic violence leading to psychological, emotional and physical harm. Nobody is able to really learn to thrive whilst being forced to learn to survive. Psychological, emotional and physical safety are essential components of transformative education.

After dropping out of secondary school, I found non-formal and informal education spaces that gave me the safety I needed to recover and the different kind of learning I needed to thrive. Through Guiding and Scouting activities, I found structured ways to develop not only knowledge, but also important skills in teamwork, leadership, cross-cultural understanding, advocacy and more. Through volunteering, I met adults who became my possibility models and enabled me to imagine not just one future but multiple possibilities of growing up and being part of a community.

While I found those things through non-formal and informal education spaces (and we need to ensure those forms of education are invested in), we also need to create a formal education system that gives everyone the opportunity to aspire and thrive.

My work now, with the Kite Trust , has two strands. The first is a youth work programme giving LGBTQ+ youth spaces to develop the confidence, self-esteem and peer connections that are still often lacking elsewhere. The second strand works with schools (as well as other service providers) to help them create those spaces themselves. We deliver the Rainbow Flag Award which takes a whole-school approach to inclusion. The underlying principle is that, if you want to ensure LGBTQ+ students are not being harmed by bullying, it goes far beyond responding to incidents as they occur. We work with schools to ensure that teachers are skilled in this area, that there is representation in the curriculum, that pastoral support in available to young people, that the school has adequate policies in place to ensure inclusion, that the wider community around the school are involved, and that (most importantly) students are given a meaningful voice.

This initiative takes the school as the system we are working to change and focuses on LGBTQ+ inclusion, but the principles are transferable to thinking about how we create intersectional, inclusive education spaces in any community or across society as a whole. Those working in the system need to be knowledgeable in inclusive practices, the materials used and content covered needs to represent diverse and intersectional experiences and care needs to be a central ethos. All of these are enabled by inclusive policy making, and inclusive policy making is facilitated by the involvement of the full range of stakeholders, especially students themselves.

If our communities and societies are to thrive in the face of tremendous challenges, we need to use these principles to ensure our education systems are fully inclusive.

Pip Gardner (pronouns: They/them) is Chief Executive of the Kite Trust, and is a queer and trans activist with a focus on youth empowerment. They are based in the UK and were a member of the Generation Equality Youth Task Force from 2019-21.

A Journey to the Stars

Isabel’s journey to pursue education in Indigenous Guatemala

School was a safe place: How education helped Nhial realize a dream

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Equality of Educational Opportunity

It is widely accepted that educational opportunities for children ought to be equal. This thesis follows from two observations about education and children: first, that education significantly influences a person’s life chances in terms of labor market success, preparation for democratic citizenship, and general human flourishing; and second, that children’s life chances should not be fixed by certain morally arbitrary circumstances of their birth such as their social class, race, and gender. But the precise meaning of, and implications for, the ideal of equality of educational opportunity is the subject of substantial disagreement (see Jencks 1988). This entry provides a critical review of the nature and basis of those disagreements.

To frame the discussion we introduce three key factors that underscore the importance of treating equality of educational opportunity as an independent concern, apart from theories of equality of opportunity more generally. These factors are: the central place of education in modern societies and the myriad opportunities it affords; the scarcity of high-quality educational opportunities for many children; and the critical role of the state in providing educational opportunities. These factors differentiate education from many other social goods. We follow this with a brief history of how equality of educational opportunity has been interpreted in the United States since the 1950s and the evolving legal understandings of equality of opportunity. Our subsequent analysis has implications for issues that are at the center of current litigation in the United States. But our philosophical discussion is intended to have wider reach, attempting to clarify the most attractive competing conceptions of the concept.

1.1 The Value of Education

1.2 the scarcity of high-quality educational opportunity, 1.3 the state regulation of education, 2. a brief history of equality of educational opportunity in the united states, 3.1 what is educational opportunity, 3.2 formal equality of educational opportunity, 3.3 meritocratic equality of educational opportunity, 3.4 fair equality of educational opportunity, 3.5 debates about fair equality of educational opportunity, 3.6 equality of educational opportunity for flourishing, 3.7 equality of educational opportunity for the labor market, 3.8 equality of educational opportunity for citizenship, 3.9 equality and adequacy in the distribution of educational opportunities, 4.1 education and the family, 4.2 disability, 4.3 the target of equal educational opportunity: individuals or groups, 5. conclusion, other internet resources, related entries, 1. equality of educational opportunity as an independent concern.

Education has both instrumental and intrinsic value for individuals and for societies as a whole. As the U.S. Supreme Court stated in its unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), “In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education”. The instrumental goals of K–12 education for individuals include access to higher education and a constellation of private benefits that follow college education such as access to interesting jobs with more vacation time and better health care; greater personal and professional mobility, better decision-making skills (Institute for Higher Education Policy 1998) and more autonomy at work. Research further shows that education levels are correlated with health and wealth: the more education a person has, the healthier and wealthier she is likely to be. At the same time, education is also considered intrinsically valuable. Developing one’s skills and talents can be enjoyable or good in itself and a central component of a flourishing life, regardless of the consequences this has for wealth or health.

In addition to the instrumental and intrinsic value of education to an individual, education is also valuable for society. All societies benefit from productive and knowledgeable workers who can generate social surplus and respond to preferences. Furthermore, democratic societies need to create citizens who are capable of participating in the project of shared governance. The correlation between educational attainment and civic participation is strong and well-documented: educated citizens have more opportunities to obtain and exercise civic skills, are more interested in and informed about politics, and in turn, are more likely to vote (Verba, Schlozman, & Brady 1995: 432–437, 445; Dee 2004).

It is therefore relatively uncontroversial to say that education is a highly valuable good to both individuals and to society, especially to democratic societies. This makes questions about who has access to high-quality educational opportunities, and how educational opportunities should be distributed, particularly important.

Questions about the just distribution of educational opportunity are especially vexing given the scarcity of resources allocated to education. Although developed societies provide some education for free to their citizens, funding for education is always in competition with the need to provide citizens with other social goods. As Amy Gutmann writes: “The price of using education to maximize the life chances of children would be to forego these other social goods” (Gutmann 1999: 129). Other basic welfare needs (e.g., housing, healthcare, food), as well as cultural goods (e.g., museums, parks, concert halls), must be weighed against public funds allocated to education, thereby making high-quality education—even in highly productive societies—scarce to some degree.

This scarcity is evident on several fronts with respect to higher education in the United States, which attracts applicants from all over the world. There is fierce competition for admission to highly selective colleges and universities in the U.S. that admit fewer than 10% of applicants. In this arena, wealthier parents sometimes go to great lengths to bolster their children’s applications by paying for tutoring, extracurricular activities, and admissions coaching—activities that can put applicants without these resources at a significant disadvantage in the admissions process. The recent “varsity blues” scandal, in which wealthy families paid millions of dollars to a college coach who promised admission to elite U.S. universities, is an extreme case in point about the degree of competition attached to selective universities.

A more urgent demonstration of the scarcity of educational opportunity in the U.S. and many other societies is evident in how access to high-quality primary and secondary education is effectively limited to children whose families can afford housing in middle-class neighborhoods, or who have access to private schools via tuition or scholarships. Despite the Brown decision’s eradication of de jure , or state-sanctioned, segregation by race in schools, public schools in the U.S. remain sharply segregated by race and by class due to de facto residential segregation. This segregation has significant consequences for poor and minority students’ educational opportunity. Given the strong correlation between school segregation, racial achievement gaps, and overall school quality, poor and minority students are disproportionately educated in lower performing schools compared to their white and more advantaged peers (Reardon 2015 and Reardon, Weathers, Fahle, Jang, and Kalogrides 2022 in Other Internet Resources ). The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these systemic background inequalities, with prolonged school closures in the U.S. disproportionately impacting low-income children who rely on schools to provide an array of social welfare services, including meals (Levinson, Cevik, and Lipsitch 2020; Levinson, Geller, and Allen, 2021).

In view of the constellation of intrinsic and instrumental goods that flow from educational opportunity, and in the context of relative scarcity, questions about how educational resources should be distributed are especially pressing as a matter of social and economic justice.

A third consideration that underscores the importance of thinking about the distribution of educational opportunities is that in most developed societies, the vast majority of such opportunities are provided through and regulated by the state. All developed societies have a legal requirement that children attend school for a certain number of years. This means that, unlike other policy levers, education is typically under the control of state institutions and has the potential to reach the vast majority of the nation’s children across racial, religious, class, and gender-based divides. And given the myriad benefits that flow from education, it is arguably a state’s most powerful mechanism for influencing the lives of its members. This makes education perhaps the most important function of government.

Since education is an integral function of government, and because it is an opportunity that government largely provides, there are special constraints on its distribution. Justice, if it requires nothing else, requires that governments treat their citizens with equal concern and respect. The state, for example, cannot justly provide unequal benefits to children on the basis of factors such as their race or gender. Indeed, such discrimination, even when it arises from indirect state measures such as the funding of schools from property taxes, can be especially pernicious to and is not lost on children. When poor and minority children see, for example, that their more advantaged peers attend better resourced public schools—a conclusion that can be drawn in many cases simply by comparing how school facilities look—they may internalize the view that the state cares less about cultivating their interests and skills. Children in this position suffer the dignitary injury of feeling that they are not equal to their peers in the state’s eyes (Kozol 1991, 2005). This harm is especially damaging to one’s self-respect because it is the development of one’s talents that is at stake; whether or not one has opportunities to gain the skills and confidence to pursue their conception of the good is central to what Rawls calls “the social basis of self-respect” (Rawls 1999: sections 65 and 67; Satz 2007: 639).

Given the importance of education to individuals and to society, it is clear that education cannot be distributed by the market: it needs to be available to all children, even children whose parents would be too poor or too indifferent to pay for it. Furthermore, if education is to play a role in equipping young people to participate in the labor market, to participate in democratic governance, and more generally to lead flourishing lives, then its content cannot be arbitrary but rather must be tailored to meet these desired outcomes. We address considerations of education’s content in subsequent sections, turning first to how equality of opportunity has been interpreted in the U.S., where we can see some of the implications of a truncated understanding of equality of opportunity in stark form.

The United States Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, in finding racially segregated public schools unconstitutional, declared that the opportunity for an education, when provided for by the state, is a “right which must be available to all on equal terms”. But de facto racial segregation persists in the U.S. and is coupled today with ever-growing class-based segregation (Reardon & Bischoff 2011). Black students are far more likely to attend high-poverty schools than their white peers (see school poverty, in the National Equity Atlas, Other Internet Resources ). The resulting, compounded educational disadvantages that poor, minority children face in the U.S. are significant. As research continues to document, the racial/ethnic achievement gap is persistent and large in the U.S. and has lasting labor market effects, whereby the achievement gap has been found to explain a significant part of racial/ethnic income disparities (Reardon, Robinson-Cimpian, & Weathers 2015; Reardon 2021 in Other Internet Resources).

Efforts to combat de facto segregation have been limited by U.S. jurisprudence since the Brown decision. Although the Supreme Court previously allowed plans to integrate schools within a particular school district (see Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education , 1970), in Milliken v. Bradley (1974) the Court struck down an inter-district busing plan that moved students across district lines to desegregate the Detroit city and surrounding suburban schools. This limitation on legal remedies for de facto segregation has significantly hampered integration efforts given that most school districts in the U.S. are not racially diverse. More recently, the U.S. Supreme Court further curtailed integration efforts within the small number of districts that are racially diverse. In its Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District decision (2006), the Court prohibited districts from explicitly using individual students’ race as a factor in school assignment plans, thereby condoning only race-neutral integration plans in what many regarded as the Court’s final retreat from redressing de facto segregation (e.g., Rebell 2009; Ryan 2007).

The persistence of race and class-based segregation in the U.S. and the educational disadvantages that follow are rooted in the U.S. system of geographically defined school districts, whereby schools are largely funded by local property taxes that differ substantially between communities based on property values. This patchwork system compounds the educational disadvantages that follow from residential segregation. The 50 states in the United States differ dramatically in the level of per pupil educational funding that they provide; indeed some of these interstate disparities are greater than the intra-state inequalities that have received greater attention (Liu 2006). The system for funding schools and the residential segregation it exacerbates—itself the product of decades of laws and conscious policies to keep the races separate—has produced and continues to yield funding inequalities that disproportionately affect poor Americans of color. The segregation of resources, with greater resources flowing to children from families in the upper quintiles of society, makes it highly unlikely that children from the lower quintiles can have an equal chance of achieving success. This is evident in research documenting the growing achievement gap between high and low-income students, which is now 30–40% greater among children born in 2001 than those born twenty-five years before (Reardon 2011: 91; Reardon 2021 in Other Internet Resources).