- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Critical Applied Linguistics

Introduction, general overviews.

- Journals and Book Series

- Critical Discourse Studies

- Critical Language Awareness and Critical Literacies

- Critical Second-Language Pedagogy

- Critical Approaches to Language Classrooms, Materials, and Testing

- Critical Approaches to Language Policy

- Decolonizing Applied Linguistics

- Language, Work, and Political Economy

- Language, Gender, and Sexuality

- Language, Race, and Raciolinguistics

- Critical Sociolinguistics

- New Directions for Critical Applied Linguistics

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- Conversation Analysis

- Dialectology

- Educational Linguistics

- Endangered Languages

- English as a Lingua Franca

- Institutional Pragmatics

- Language Contact

- Language for Specific Purposes/Specialized Communication

- Language Ideologies and Language Attitudes

- Language Nests

- Language Policy and Planning

- Language Shift

- Language Standardization

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Prescriptivism

- Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

- Linguistic Relativity

- Minority Languages

- Politeness in Language

- Positive Discourse Analysis

- Register and Register Variation

- Second Language Pragmatics

- Second Language Vocabulary

- Second Language Writing

- Second-Language Reading

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation

- Variationist Sociolinguistics

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Cognitive Grammar

- Edward Sapir

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Critical Applied Linguistics by Alastair Pennycook LAST REVIEWED: 27 October 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 October 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0280

Critical applied linguistics is a field of inquiry and practice that can be understood in several ways. It brings a critical focus—where the critical is understood as social critique rather than critical thinking—to applied linguistic work. A central goal is to connect questions of domination (contingent and contextual effects of power), disparity (inequitable access to material and cultural goods), discrimination (ideological and discursive frames of exclusion), difference (constructions and realities of social and cultural distinction), and desire (operations of ideology, agency, identity, and transformation) to applied linguistic concerns. A key challenge for critical applied linguistics is therefore to find ways of understanding relations between, on the one hand, concepts and critiques of society, ideology, neoliberalism, colonialism, gender, racism, or sexuality and, on the other hand classroom utterances, translations, conversations, genres, second-language acquisition, media texts, and other common applied linguistic concerns. Whether it is critical text analysis, or an attempt to understand implications of the global spread of English, a central issue is always how a classroom, text, or conversation is related to broader social cultural and political relations. Critical applied linguistics suggests therefore certain domains of inquiry—language and migration, workplace discrimination, anti-racist education, language revival, for example—but also insists that all domains of applied linguistics—classroom analysis, language testing, sign language interpreting, language and the law—need to take into account the inequitable operations of the social world, and to have the theoretical and practical tools to do so effectively. Critical applied linguistics can also be seen as the intersection between different critical domains of work—such as critical pedagogy, critical literacies, and critical discourse analysis—where these pertain to applied linguistic concerns (critical second-language pedagogies for example). There are also several domains that carry labels other than “critical”—such as anti-racist education, feminist discourse analysis, queer theory—that are equally part of the picture. As a domain of applied work, critical applied linguistics seeks not just to describe but also to change inequality through forms of research, pedagogy, and activism.

Although people have doubtless been doing critical applied linguistics for a long time, the term seems to have been first used in Pennycook 1990 , followed by an introductory text, Pennycook 2001 , and the substantially revised second edition, Pennycook 2021 . Other books with a more specific focus nonetheless provide good overviews of the field, including Benesch 2001 and Chun 2015 , focusing on teaching English for academic purposes from a critical perspective. The edited book Norton and Toohey 2004 similarly brings a focus on language learning and critical pedagogy together. From an applied sociolinguistic perspective, Piller 2016 provides an introduction to issues of language diversity and social justice, while Joseph 2006 provides a broad overview of why we must always understand language politically. In an introduction to a special issue of the journal Critical Inquiry in Language Studies , Kubota and Miller 2017 gives an overview of current concerns around critical language education.

Benesch, S. 2001. Critical English for academic purposes: Theory, politics, and practice . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

DOI: 10.4324/9781410601803

This book combines English for academic purposes (EAP) and critical pedagogy, arguing that students need to both learn and learn to question academic norms in English.

Chun, C. 2015. Engaging with the everyday: Power and meaning making in an EAP classroom . Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Combines critical literacy pedagogy and English for academic purposes (EAP) and shows how a teacher gains awareness of power and meaning making in her classroom.

Joseph, J. 2006. Language and politics . Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.3366/edinburgh/9780748624522.001.0001

Argues that language is political from top to bottom, from the level of individual interaction to the formation of national languages.

Kubota, R., and E. Miller. 2017. Re-examining and re-envisioning criticality in language studies: Theories and praxis. In Special issue: Re-examining and re-envisioning criticality in language studies. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 14.2–3: 129–157.

DOI: 10.1080/15427587.2017.1290500

Re-examines the meaning of criticality in language studies from different theoretical perspectives, arguing for the importance of praxis.

Norton, B., and K. Toohey, eds. 2004. Critical pedagogies and language learning . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

A key edited text bringing second-language learning and critical pedagogy together.

Pennycook, A. 1990. Towards a critical applied linguistics for the 1990s. Issues in Applied Linguistics 1.1: 8–28.

DOI: 10.5070/L411004991

Though critical applied linguistic work clearly predates its naming, this was the first article to describe the field in these terms, and lay out a critical applied linguistic agenda.

Pennycook, A. 2001. Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

DOI: 10.4324/9781410600790

A widely cited introduction to the field, pulling tother work in related areas and explaining key concepts in critical theory and applied linguistics.

Pennycook, A. 2021. Critical applied linguistics: A critical re-introduction . New York: Routledge.

DOI: 10.4324/9781003090571

A thoroughly revised version of the earlier text, taking into account political and epistemological changes in the intervening years and arguing for a renewed activist agenda.

Piller, I. 2016. Linguistic diversity and social justice: An introduction to applied sociolinguistics . Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199937240.001.0001

Focuses on linguistic dimensions of economic inequality, cultural domination, and barriers to political participation, drawing attention to a wide range of contexts of linguistic injustice.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Linguistics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Acceptability Judgments

- Accessibility Theory in Linguistics

- Acquisition, Second Language, and Bilingualism, Psycholin...

- Adpositions

- African Linguistics

- Afroasiatic Languages

- Algonquian Linguistics

- Altaic Languages

- Ambiguity, Lexical

- Analogy in Language and Linguistics

- Animal Communication

- Applicatives

- Applied Linguistics, Critical

- Arawak Languages

- Argument Structure

- Artificial Languages

- Australian Languages

- Austronesian Linguistics

- Auxiliaries

- Balkans, The Languages of the

- Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan

- Berber Languages and Linguistics

- Biology of Language

- Borrowing, Structural

- Caddoan Languages

- Caucasian Languages

- Celtic Languages

- Celtic Mutations

- Chomsky, Noam

- Chumashan Languages

- Classifiers

- Clauses, Relative

- Clinical Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Colonial Place Names

- Comparative Reconstruction in Linguistics

- Comparative-Historical Linguistics

- Complementation

- Complexity, Linguistic

- Compositionality

- Compounding

- Computational Linguistics

- Conditionals

- Conjunctions

- Connectionism

- Consonant Epenthesis

- Constructions, Verb-Particle

- Contrastive Analysis in Linguistics

- Conversation, Maxims of

- Conversational Implicature

- Cooperative Principle

- Coordination

- Creoles, Grammatical Categories in

- Critical Periods

- Cross-Language Speech Perception and Production

- Cyberpragmatics

- Default Semantics

- Definiteness

- Dementia and Language

- Dene (Athabaskan) Languages

- Dené-Yeniseian Hypothesis, The

- Dependencies

- Dependencies, Long Distance

- Derivational Morphology

- Determiners

- Distinctive Features

- Dravidian Languages

- English, Early Modern

- English, Old

- Eskimo-Aleut

- Euphemisms and Dysphemisms

- Evidentials

- Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics

- Existential

- Existential Wh-Constructions

- Experimental Linguistics

- Fieldwork, Sociolinguistic

- Finite State Languages

- First Language Attrition

- Formulaic Language

- Francoprovençal

- French Grammars

- Gabelentz, Georg von der

- Genealogical Classification

- Generative Syntax

- Genetics and Language

- Grammar, Categorial

- Grammar, Construction

- Grammar, Descriptive

- Grammar, Functional Discourse

- Grammars, Phrase Structure

- Grammaticalization

- Harris, Zellig

- Heritage Languages

- History of Linguistics

- History of the English Language

- Hmong-Mien Languages

- Hokan Languages

- Humor in Language

- Hungarian Vowel Harmony

- Idiom and Phraseology

- Imperatives

- Indefiniteness

- Indo-European Etymology

- Inflected Infinitives

- Information Structure

- Interface Between Phonology and Phonetics

- Interjections

- Iroquoian Languages

- Isolates, Language

- Jakobson, Roman

- Japanese Word Accent

- Jones, Daniel

- Juncture and Boundary

- Khoisan Languages

- Kiowa-Tanoan Languages

- Kra-Dai Languages

- Labov, William

- Language Acquisition

- Language and Law

- Language Documentation

- Language, Embodiment and

- Language Geography

- Language in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Language Revitalization

- Language, Synesthesia and

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of the Americas, Indigenous

- Languages of the World

- Learnability

- Lexical Access, Cognitive Mechanisms for

- Lexical Semantics

- Lexical-Functional Grammar

- Lexicography

- Lexicography, Bilingual

- Linguistic Accommodation

- Linguistic Areas

- Linguistic Landscapes

- Linguistics, Educational

- Listening, Second Language

- Literature and Linguistics

- Machine Translation

- Maintenance, Language

- Mande Languages

- Mass-Count Distinction

- Mathematical Linguistics

- Mayan Languages

- Mental Health Disorders, Language in

- Mental Lexicon, The

- Mesoamerican Languages

- Mixed Languages

- Mixe-Zoquean Languages

- Modification

- Mon-Khmer Languages

- Morphological Change

- Morphology, Blending in

- Morphology, Subtractive

- Munda Languages

- Muskogean Languages

- Nasals and Nasalization

- Niger-Congo Languages

- Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages

- Northeast Caucasian Languages

- Oceanic Languages

- Papuan Languages

- Penutian Languages

- Philosophy of Language

- Phonetics, Acoustic

- Phonetics, Articulatory

- Phonological Research, Psycholinguistic Methodology in

- Phonology, Computational

- Phonology, Early Child

- Policy and Planning, Language

- Possessives, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Cognitive

- Pragmatics, Computational

- Pragmatics, Cross-Cultural

- Pragmatics, Developmental

- Pragmatics, Experimental

- Pragmatics, Game Theory in

- Pragmatics, Historical

- Pragmatics, Institutional

- Pragmatics, Second Language

- Pragmatics, Teaching

- Prague Linguistic Circle, The

- Presupposition

- Psycholinguistics

- Quechuan and Aymaran Languages

- Reading, Second-Language

- Reciprocals

- Reduplication

- Reflexives and Reflexivity

- Relevance Theory

- Representation and Processing of Multi-Word Expressions in...

- Salish Languages

- Sapir, Edward

- Saussure, Ferdinand de

- Second Language Acquisition, Anaphora Resolution in

- Semantic Maps

- Semantic Roles

- Semantic-Pragmatic Change

- Semantics, Cognitive

- Sentence Processing in Monolingual and Bilingual Speakers

- Sign Language Linguistics

- Sociolinguistics, Variationist

- Sociopragmatics

- Sound Change

- South American Indian Languages

- Specific Language Impairment

- Speech, Deceptive

- Speech Perception

- Speech Production

- Speech Synthesis

- Switch-Reference

- Syntactic Change

- Syntactic Knowledge, Children’s Acquisition of

- Tense, Aspect, and Mood

- Text Mining

- Tone Sandhi

- Transcription

- Transitivity and Voice

- Translanguaging

- Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

- Tucanoan Languages

- Tupian Languages

- Usage-Based Linguistics

- Uto-Aztecan Languages

- Valency Theory

- Verbs, Serial

- Vocabulary, Second Language

- Voice and Voice Quality

- Vowel Harmony

- Whitney, William Dwight

- Word Classes

- Word Formation in Japanese

- Word Recognition, Spoken

- Word Recognition, Visual

- Word Stress

- Writing, Second Language

- Writing Systems

- Zapotecan Languages

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 February 2021

Exploring linguistic features, ideologies, and critical thinking in Chinese news comments

- Yang Gao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5888-6033 1 &

- Gang Zeng 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 39 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7928 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

- Language and linguistics

This study explores linguistic features, ideological beliefs, and critical thinking in news comments, which are defined as the comments from readers to news posts on social media or platforms. Within the overarching framework of critical discourse analysis, a sociocognitive approach was adopted to provide detailed analyses of the studied constructs in sampled news comments. In terms of the data collection and analysis, sampled social media, news columns, and news comments were selected, and then 19 college students were interviewed for their responses to different news topics. The primary findings of the study include: (1) personal and social opinions are representations of ideological beliefs and are fully presented through news comments, (2) these personal and social ideological beliefs may diverge or converge due to critical thinking, (3) critical thinking helps commenters form their personal and social ideologies, and then helps them choose the linguistic forms they believe fit their news comments, (4) news topics, however, vary in informing commenters’ critical thinking ability. Finally, a sociocognitive model for studying linguistic forms, ideologies, and critical thinking was proposed in the study.

Similar content being viewed by others

The language of opinion change on social media under the lens of communicative action

The art of rhetoric: persuasive strategies in Biden’s inauguration speech: a critical discourse analysis

The processing and evaluation of news content on social media is influenced by peer-user commentary

Introduction.

Over the decades, the majority of the existing literature on news text has focused on how the news is framed from an author’s perspective; however, research on news text from commenters is far less developed. Therefore, we chose a specific type of underdeveloped news text, i.e., news comment, as the focal text for this study. In the study, news comments were not defined as the long commentary articles professionals or journalists write to comment on specific news; instead they were the real-time, short comments or prompts from readers. We took the theoretical premise from van Dijk ( 1997 ) that news text is ideological in nature (p. 197) and explored how critical thinking and linguistic forms, as different constructs, may inform the commenters of revealed ideologies through a specific news text. Before we elaborate on the theoretical framework, we present some synopses of the terms or constructs, i.e., ideology and critical thinking, the focal components of the study.

Van Dijk ( 2006 ) defined ideologies as “systems of ideas” and sociocognitively “shared representations of social groups, and more specifically as the axiomatic principles of such representations” (p. 115). Ideologies are thus “the basic frameworks for organizing the social cognitions shared by members of social groups, organizations or institutions” (van Dijk, 1997 , p. 18) and penetrate all discourse and communication, including media text as one of the predominant forms. From a critical literacy perspective, Tolson ( 2001 ) argued that the informational content conveyed through the mass media is ideology-based; it reproduces and strengthens social relations between the oppressed and the oppressors. Therefore, news commentary, as one type of media text, shows the audience’s attitudes towards a particular news, topic, or event; it conveys the ideological beliefs that audiences hold about the news, topics, or events. Fairclough ( 2006 ) argued that understanding how audiences interpret and respond to the news is helpful to analyze their ideologies. However, the explicitness or vagueness of the ideological beliefs revealed through media discourse or news text makes research on this topic difficult.

Ideologies include cognitive and social ideologies and these two types of ideologies may converge or diverge. We argue that the convergence or divergence of these two types of ideologies depends on critical thinking, another construct that we explore in the study. The notion of critical thinking may be traced to different fragmented tenets of critical discourse analysis (CDA). At the same time, it is one of the core components in interpreting discourse and text (Fairclough, 2006 ). Critical thinking is related to the notion of reflexivity in some classic CDA works; it may refer to both a general principle of doing scientific research and a property of language use, subjectivity, or practice (Chouliaraki and Fairclough, 1999 ; Feustel et al., 2014 ; Zienkowski, 2017 ). For example, Fairclough ( 2010 ) stated that

“Late modernity is characterized by increasing reflexivity including language reflexivity, and people need to be equipped both for the increasing knowledge-based design of discursive practices within economic and governmental systems, and for critique and redesign of these designed and often globalized practices” (p. 603).

Multiple approaches have been used to study linguistic features, ideologies, and critical thinking. Studying these constructs is a challenging task. Because the complex world is dynamic and changes regularly, a specific and individual framework may not be able to interpret or explain the constructs thoroughly. Furthermore, some the focal components or tenets of some theories or frameworks may overlap, which complicates the selection of a theoretical framework. For the current study, we decided to pinpoint our focal constructs and then align these constructs with appropriate theories. While CDA has been applied to studies on language and ideology for decades, it has rarely been considered with regard to news comments, particularly in the Chinese context. This research thus aims to study the linguistic features of news comments through major social media in China and to further explore ideological and critical thinking incidents in these commentary responses. Specifically, we attempt to explore the following issues: (1) the typical linguistic forms, ideologies, and critical thinking in news comments and (2) how these constructs inform each other in news comments.

Theoretical considerations

Under the overarching concept of CDA, different focal approaches or schools have developed over the years, including but not limited to: Fairclough’s Critical Approach, Wodak’s Discourse-historical Approach, and van Dijk’s sociocognitive approach (SCA). Fairclough’s approach has been regarded as the foundational and most classic approach. It perceives language as a social process in which discourse produces and interprets text; however, this process is not random or free but is socially conditioned. Fairclough’s approach has infrequently focused on media text, which then has been extended and developed by Wodak and van Dijk. Unlike Fairclough’s approach, Wodak’s approach focuses on a macroperspective as national identity and is concerned with strategies that can be adapted to achieve specific political and psychological goals. To understand this bigger picture, Wodak’s approach includes historical analysis and considers the sociocultural background of the text studied. In terms of media text study, Wodak and Busch ( 2004 ) analyzed different approaches in media text, from mapping out historical development in CDA to advanced qualitative approaches in critical linguistics and CDA.

SCA resembles Fairclough’s approach in connecting the microstructure of language to the macrostructure of society (Kintsch and van Dijk, 1978 ). However, van Dijk ( 1993 ) extended the field by transplanting social cognition as the mediating tool between text and society. He defined social cognitions as “socially shared representations of societal arrangements, groups, and relations, as well as mental operations such as interpretation, thinking and arguing, inferencing and learning” (p. 257). Similar to Wodak, van Dijk ( 1991 ) applied his approach of discourse analysis to media texts and firmly believed that one area in which discourse can play an important role is in the (re)production of racism inequality through discourse. The major point of his work is that “racism is a complex system of social and political inequality that is also reproduced by discourse” (van Dijk, 2001 , p. 362). Van Dijk’s SCA thus focuses on the schemata through which minorities are perceived and illustrated as well as in headlines in the press.

We firmly believe that no single approach mentioned above perfectly fits all the constructs to be studied in the research, but tenets of different approaches work in different ways to inform the findings of the study. We went deeper into these frameworks and determined that an SCA approach under CDA may better inform the study and thus serve as the theoretical foundation of the study; it works better than other approaches in mapping out relationships among language, cognition in which critical thinking is embedded, and ideologies. However, we did not adhere to a specific school or approach in CDA but instead incorporated different tenets among three different schools in CDA into our study. For example, we referred to a textual analysis perspective from the three-dimensional framework (Fairclough, 1995 ) and extended and interpreted our findings by incorporating social and national ideologies from Wodak ( 2007 ) and social/personal cognition from van Dijk ( 1997 ).

In addition, we reinterpreted CDA from an audience or commenter perspective rather than the author perspective. Our rationale is that the text an author or speaker has framed may serve discursive and social purposes. The author or speaker in this way serves as the initiator of the discursive and social practices. However, this is not the case from an audience or reader perspective. An audience or reader is not the initiator of the actions or practices; he or she may be the person who accepts or rejects the practices. Therefore, we argue that examining ideological and critical thinking constructs in news comments may reveal audiences’ perceptions of and attitudes towards certain practices and even the power behind these practices.

Research methodology

Wodak and Meyer ( 2015 ) concluded that “CDA does not constitute a well-defined empirical method but rather a bulk of approaches with theoretical similarities and research questions of a specific kind” (p. 27). They further explained that methodologies under CDA typically fall into a hermeneutic rather than an analytical-deductive approach. The hermeneutic style requires detailed analyses and reasoning that fit the theoretical framework in the study.

While it might be a challenging task to pinpoint a specific methodology, we followed appropriate guidance in conducting this CDA study. As classic methodological guidance, Wodak and Meyer ( 2015 ) provided a diagrammed process for conducting CDA studies, including theory , operationalization , discourse/text , and interpretation . Theories provide the soil for the conceptualization and selection of theoretical frameworks; operationalization demands specific procedures and instruments; discourse/text is a platform to convey the information; and interpretation is the stage to examine assumptions. One of the major components that guide the methodological design and selection is operationalization, which requires specific procedures and instruments. Therefore, we first selected social media and sampled news and then conducted interviews among 19 college students in a typical research-based university in Northeast China.

Selection of the social media and news columns

Liu ( 2019 ) synthesized social media user reports in the first quarter of 2018 and listed the top 10 social media software and apps that people used in China, which included payment apps (e.g., Alipay), shopping platforms and/or apps (e.g., Taobao), and other platforms and/or apps for entertainment or regular social purposes (e.g., WeChat, Baidu, Sina). According to the poll, we selected WeChat (1040 million users), Baidu search (700 million users), and Sina vlog (392 million users) as the three social media we used for the current study.

Among the three largest social media platforms, Baidu News has a specific classification of 12 news columns, which include domestic affairs, international affairs, military and army, finance and economics, entertainment, sports, internet, technology, gaming, and beauty. The column military and army was an outlier in the selection because it is heavily political or ideological in the context; gaming and beauty were also regarded as two outliers that were highly gender-oriented. After a screening process, we thus deleted and synthesized these columns into six, including domestic/international affairs, finance, entertainment, sports, technology, and game.

Then, one or two news samples were selected under each topic, considering whether the samples might solicit rich information from the interviewees or commenters. For analysis purposes, we collected representative responses with high recognition of the selected news samples. We then conducted a rough analysis of the selected news and corresponding comments and discussed the appropriateness of the news samples. We finalized 12 sampled news items with more than 30 comments and charted them in Table 1 .

Participants

Participants in the study included both public users of social media and undergraduates from an eastern university in China. First, representative news reviews in six categories, including finance, sports, international, domestic, entertainment, and technology, were collected. The comment publishers were social media users from Baidu, Sina Weibo, Surging News, etc.

Additionally, we conducted individual interviews with 19 undergraduates from a university in Northeast China. The interviews focused on the research participants’ opinions on the news. Among the participants, there were three freshmen, 14 sophomores, and two juniors. The ratio of males to females was 9/10. The research participants were from eight different schools: the Law School, the School of Foreign Languages, the School of Sciences, the School of Maritime Electrical Engineering, the School of Transportation Engineering, the Navigation School, the School of Information Science and Technology, and the School of Public Management and Liberal Arts (see Table 2 ).

We conducted one-on-one interviews with 19 undergraduates from a research-based university in Northeast China. The participants of the research were from diverse backgrounds, and the interviews mainly focused on the participants’ views on the news. To ensure the reliability of the results, the participants were not informed until the interview began on site. We conducted the interviews in a casual, conversational format. Each interview lasted ~20 min and aimed to solicit the students’ prompt, real-time responses to the column news. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed for data collection and analysis purposes.

An interview protocol was designed based on the sampled news analysis. The interview protocol consisted of news subjects and guiding sentences. The news subjects were the originally quoted news, while the guiding sentences were directed to each individual news sample. The protocol questionnaire was used to guide the participants to go through the news and then make an instant response.

Data collection and analysis

With the designed interview protocol, corresponding interviews were conducted with 19 college students in the form of casual conversations. Through the WeChat platform and other media, university students’ personal thoughts about specific news were recorded because most of the interviewees had chosen to use text and audio records in WeChat to express themselves. The researchers collected and organized the obtained information and added it to the information charts after acquiring the permission of the interviewees, who were selected from different year levels and faculties. Preliminarily, there were a total of 25 participants who attended the interview and provided nearly 50 pieces of interview information. The researchers finalized the participant size to 19 by deleting some outlier responses. Finally, data collected from the two primary methods were integrated by the researchers and then categorized into four sections, including news content, typical responses, interview responses, and analyses.

Detailed analyses from SCA worked to guide the specific methodology used for the current study due to its theoretical foundation and constructs, including linguistic forms, ideology, and critical thinking, which we wanted to explore. Specifically, SCA suggests six steps of analyses, including semantic macrostructures (topics and macro propositions), local meanings, “subtle” formal structures, global and local discourse forms or formats, linguistic realizations, and the context (Wodak and Meyer, 2015 ). Some types of analyses focus on linguistic forms and figures of speech analysis, some of the analyses focus on literal or connotative meanings, and others on context. It is worth mentioning that not all the analyses can be completely conducted in one single study because some analyses do not fit a specific study. However, these analyses offered methodological insights for the current study. We took steps in collecting different sources of data and analyzed the data in different ways.

Linguistics: lexical, syntactic, and figurative speech features

Van Dijk ( 1995 ) argued that the first step for analysts in CDA studies is to “explore the structures and strategies of text and talk to attend in order to discover patterns of elite dominance or manipulation ‘in’ texts” (p. 19). As van Dijk ( 2006 ) stated, “Although general properties of language and discourse are not, as such, ideologically marked, systematic discourse analysis offers powerful methods to study the structures and functions of underlying ideologies” (p. 115). Therefore, linguistic forms are excellent representations and tools to study ideologies in text. Linguistic features of the text, as a formal property of the text (Fairclough, 1989 , p. 26), are explored in the descriptive stage. One of the features is that idioms, as a way to show respondents’ attitudes and ideologies through the linguistic form, are widely used in the news comments. Idioms are generally used among people with certain cultural capitals. They are socially conditioned, and outgroup people may find them difficult to comprehend. By using idioms, news respondents present shared sociocultural knowledge that can only be easily processed among ingroup people. In the study, many idioms were found in the news comments, such as “ hai ren zhi xin bu ke you, fang ren zhi xin bu ke wu (guard against all intents to harm you, but harbor no intention to harm others)”, “ yan zhen yi dai (be on guard)”, “ jing dai hua kai (wait for the blossom)”, “ zuo wu xu xi (be fully seated)”, and “ qi er yi ju (an effortless job to do)”. The idiomatic expression resonates with what SCA argues are local meanings (Wodak and Meyer, 2015 ) because it focuses on the meanings in the specific, local context.

In addition, connotative meanings of the lexical terms that were connected with figure-of-speech usage appeared in the news commentary, such as, “It might not be good to comment on people’s backyard if one had never lived in Hong Kong.” The backyard in the sentence has a connotative meaning and is used as a metonymy. The feature relates to dialectical and regional terms; some of these cultural capitals behind these terms are deeply rooted in particular regions. Again, the lexical choice, e.g., the backyard, indicates an ingroup–outgroup dichotomy and thus embodies certain personal or social ideologies. A typical SCA approach suggests that language realization analysis requires a figure of speech analysis, which helps map out the local and global meanings of a specific excerpt (van Dijk, 1995 ; Wodak and Meyer, 2015 ).

In terms of the syntactic structure, the research showed that social media platforms and interviewees mainly used relatively complex, notably parallel sentence structures. Examples are the use of the metaphor in “Martial art is not equal to Kungfu. Art involves manifestation and form, while Kungfu involves speed and flexibility. Basketball is a kind of Kungfu, not martial arts. Chinese athletes lack Kungfu but have little success in martial arts” (News, Responsible for the Failure of the Chinese Men’s Basketball Team? A Dejiang, He is a Man, Zhou Qi Needs Care ) or “Like art, the sport has no borders” (News, After Chinese Netizens, Boycotted the NBA, the NBA China Game is Still Fully Seated, and Some People Even Let the Player Sign on the Chinese Flag ). The use of rhetorical techniques, such as metaphors, also increased the complexity of the syntactic structure.

The parallel structure served two primary purposes: it restated the points that the news respondents or the college students attempted to emphasize, and it fostered either a provoking or an emotional context that resonated with the news commentary readers. For example, “Since the start of the match, the Chinese women’s volleyball team has defeated South Korea, vanquished Cameroon, edged out Russia, knocked out Japan, and beaten Brazil” (News: The Chinese Women’s Volleyball Team beat Brazil, Warming up before the Sino-U.S. Confrontation ). Another example with repeated terms and concepts was “Ball, the ball, is just a ball; the country is always behind you” (News: After Chinese Netizens Boycotted the NBA, the NBA China Game is Still Fully Seated, and Some People Even Let the Player Sign on the Chinese Flag ). In the responses in the first example, repetitive verb forms fostered an accelerating sense of excitement for Chinese readers, who may feel proud to be a member of that winning country. In the other example, the repeated term ball puts readers at the front of national and personal interests and may cause a provoking sense of quitting the game for the sake of national interests.

Ideological and critical thinking accounts

Van Dijk ( 1995 ) argued,

“[T]he social functions of ideologies are, among others, to allow members of a group to organize (admission to) their group, coordinate their social actions and goals, to protect their (privileged) resources, or, conversely, to gain access to such resources in the case of dissident or oppositional groups” (p. 19).

We argue that linguistic features as mentioned above did not directly form or express the ideologies of news commenters or interviewees; instead, they indirectly indicated or expressed the ideologies of these commenters and interviewees. This may result from the nature of news commentary, which is a way to represent commenters’ views or opinions and presents certain personal or social ideologies. Through the textual analysis, we found that the way the news is framed may arouse commenters’ acceptance or rejection of the content of news text, which indicates their sense of group relations and structures (van Dijk, 1995 ). For example, a strong sense of ingroup affiliation was revealed through most of the news commentary and interviewee responses. News commenters and interviewees had a strong sense of pride and praise for news related to the economic or political power of China. Exemplar sentences of pride and praise for China’s strength included, “The increase in the creativity of Chinese companies in recent years shows the great potential of China’s high-tech industry,” “Support domestic products!” and “The Chinese Women’s Volleyball Team won the 13th Women’s Volleyball World Cup with a record of 11 wins….” Van Dijk ( 1995 ) argued, “The contents and schematic organization of group ideologies in the social mind shared by its members are a function of the properties of the group within the societal structure” (p. 19). This is true even when social cognition may conflict with personal cognition. In this study, most interviewees had a strong sense of honor in their home country even when facing conflicts between personal interests and national interests.

While ideologies define and explain the similarities in the social practices of social members, they also leave room for individual variation and differences, which contributes to a “dynamic and dialectic” relationship between social ideology and personal cognition (van Dijk, 1995 , p. 19). Personal cognition or ideology thus becomes an embodiment of critical thinking (van Dijk, 2006 ). Van Dijk ( 2006 ) explained that the analysis of ideologies is actually a critical analysis because ideologies may be used as a foundation to study critical thinking. Studying whether certain ideologies and personal cognition diverge or converge may indicate how critical thinking works. In our study, we found the emergence of critical thinking in the form of multiple, diverse perspectives in news reviews, comments, or responses. For example, the news responders were able to interpret news based on the pros and cons or multiple perspectives; we connect that multiperspective analysis with their critical thinking ability. The analysis of critical thinking is above the ideological analysis in the news commentary; it helped the researchers evaluate whether the respondents’ or commenters’ patriotism was rational. For example, in the commentary “we should not pursue foreign products too much, but the advanced technology contained in the foreign products is something we can learn from,” instead of being blindly patriotic, the respondent may show a sense of rationalism in his/her response: stopping the purchase of foreign products is hardly equal to stopping the learning of advanced technology in designing or manufacturing these products. Another example is “Sports, like art, has no national boundaries, but one should stand firmly on the side of the nation as a Chinese when national political issues are involved in sports.”

Topics and news comments

We also found that news topics may inform linguistic features, ideological beliefs, and critical thinking accounts in the news comments in different ways. Wodak and Meyer ( 2015 ) explained that topics are an important semantic macrostructure to be addressed in SDA analyses.

Topics and languages

Generally, news topics varied in their power to generate lexical and syntactical structures. Some topics on politics, the economy, and technology led the commenters to be more rigorous in their wording and phrasing, and their commentary language was more professional and formal than it was for other topics from entertainment and sports. The following example is one response to the news on China’s development of 5G technology: “First, it shows the progress China has made in science and technology in recent years, and the relevant policies are effective… second, ….” The responder provided more details and even listed points for the reasoning. The commentary was not simply in a narrative or colloquial format but instead was organized in a logical way. The same type of commentary was revealed through the news on “The Giant Carrefour Lost to China….” Sample responses included the following: “With the development of the commodity retail industry, there is a need for consumers’ needs to be met in the first place. The consumer values quality, cost efficiency, and then brands. To keep consumers within long-term development, service is another vital part. Next….” The sampled interview response also indicated the interviewed responder’s analysis of the rationale for why Carrefour had lost its market shares in China.

On the other hand, we found that comments on entertainment topics were presented in a more informal way than other issues. For example, when some responders were interviewed about their responses to news related to stars or celebrities’ clothing or behavior, they directly expressed their belief that it was not their business or was a personal issue for the stars or celebrities. The closer the topic was to life, the simpler the language was in terms of wording and expressions.

Topics, ideologies, and critical thinking

In terms of how topics related to or informed ideological beliefs in news commentary, we found that the research samples presented significant patriotic tendencies in news comments on science and technology, sports, and international and domestic affairs. These topics included national infrastructure and economic development, national interests, and sports competitions with other countries, which might easily inspire the national self-esteem and national self-confidence of newsreaders and respondents. The responses to these news topics in the sample reflected strong support for the home country. Most of these responses were affirmative and positive, showing the commenters’ chauvinistic attitudes towards specific nationalist characteristics or stating factual evidence of China’s progress in a positive way. For example, responses to the news “China has the world’s first 5G standard necessary patents” were mostly positive and affirming, with the majority applauding and supporting the development of the technology in China. A few comments presented a critical, dialectical analysis on its advantages and disadvantages. A critical, dialectical analysis serves as a principal way to motivate and probe a thinker, with its goal to push the thinker go beyond the ideas and values, their significance, and their limitations. Dialectical thinking is a way of thinking that replaces or serves as a counterpart of logical thinking. Originally derived from the tenets of German philosopher Hegel (e.g., 1971 , 1975 ), dialectical thinking promotes tenets including being self-critical and taking nothing for granted. Dialectical thinking focuses on how reflectivity helps a thinker extend the dimensions of his/her repertoire of a certain concept or thing. Among ways of dialectical thinking is the Marxist dialectic which applies to the study of historical materialism and deeply influences Asian culture.

Marxist materialism is melded to the Hegelian dialectic (e.g., Marx, 1975 ). Marx opposes metaphysics, which he considered unscientific but instead asserted that reality was directly perceived by the observer without an intervening conceptual apparatus. He then used the dialectic, a metaphysical system which he thought to be empirically true. The Marxist dialectic considers theory and practice to be a single entity and that what men actually do demonstrates the truth. In the same vein, Dewey’s logic including learning by doing is also influenced by Hegel’s dialectical thinking, which highlights the experimental situation rather than from an externally validated formal system (Rytina and Loomis, 1970 ).

In the current study, we argued that Marxist dialectical analysis or thinking helps commenters or readers think about and interpret news from a multidimensional, unstable, and empirical way. We did find in a critical, dialectical way of thinking in a few news comments. Specifically, regarding the way topics related to or informed critical thinking in news commentary, we found that responses to news topics on entertainment and domestic topics diverged, which indicated different voices or perspectives on the news. Respondents tended to provide more critical thinking accounts on the news. The awareness of critical thinking is mainly reflected in the fact that the commenter can analyze the event from multiple aspects rather than interpreting the problem in isolation or can be aware that his or her point of view starts from only one perspective. For example, responses to the news on Wang Yuan smoking in public places and Rayza’s airport look diverged in the different opinions of the respondents. Some believed stars or celebrities should have their own privacy and identity, whereas others believed they should set good examples for the public and avoid traditionally defined misbehaviors. Another example was found in the news comments that stated that how much a person earns could lead to financial independence or help people be self-sufficient. The following is a sampled response:

“Simply talking about financial freedom is not rational, as it is hard to define what is it. Financial freedom may come from one’s inner satisfaction. For example, successful businessmen have tons of money, but there are also many things for them to consider, including social responsibility and company operation. Money, for them, cannot be spent at will….”

We detected rational analysis from the responder, who was able to analyze the news from multiple perspectives in a logical and rational way. Examples in the responder’s commentary made sense, suggesting that one’s self-sufficiency cannot be measured simply by how much he/she earns or possesses.

Linguistic features, discursive practice, and social practice

Drawing upon systemic functional grammar (Halliday, 1978 ), Fairclough acknowledged that language is, to some extent, a social practice. The reason why the form of language is mainly determined by its social function is revealed in the perspective of the social communication function of discourse. Discourse is not only seen as a form of language but is also embodied as a social practice. CDA essentially studies society from a linguistic perspective and links linguistic analysis with social commentary.

News comments in the study indicate the respondents’ attitudes, which may render any discursive practice in the form of speech acts (Fairclough, 1989 , 1995 ). For example, some commenters held subjective views against smoking in public places, dissatisfaction with cyber violence specific to women’s clothing, and positive support and encouragement of the Chinese Women’s Volleyball Team and the Chinese Men’s Basketball Team. The social participation of the respondents was revealed through the text, which represents discursive and social practice. The commenters whose comments reflected multifaceted and multilayered thinking or ideology had a high degree of social participation, and those whose comments had explicit attitudes towards real life had a high degree of social participation. In addition to ideology, the responses served a social function (van Dijk, 1995 ). For instance, “smoking in public is not appropriate” was a manifestation of social care that was generally accepted by the public, while “living in other people’s eyes” was a manifestation of guiding citizens to have their own judgments and values and to advocate for ideological improvement. The comments on 5G and Apple showed that people paid close attention to the development of science and technology in the country and the need for high-tech ways to improve life. Support and encouragement for the Chinese women’s volleyball team and the men’s basketball team played a social role in increasing patriotism.

The younger generation’s ideology in China

One of the hidden themes in the study is the young generation’s language or new literacy, with sample features such as slang or buzzwords they use in daily life. For example, “ liang liang (failure),” “ sha diao (idot),” “ zhong cao (attractive),” “ di biao zui qiang (the most powerful one),” and “ shen xian da jia (competition among the elites)” were frequently cited in their comments; some of these terms are from movies or social media, while some are terms coined in their peer communication. These terms represent their generation and show their uniqueness and differences from their parents’ generations. Behind these terms stand their personal beliefs and ideologies.

In addition, by analyzing the critical thinking ability of college students’ news reviews, the researchers found that college students were prone to express their views and value all civil rights and national sovereignty in their news commentary. Students’ comments were relatively independent, rational, and critical. Fairclough ( 1995 ) argued that the undiscovered information of power, ideology, and language in news reports could be investigated and explained through institutional context and societal context. Because the Chinese ideology is deeply rooted in culture, the power of patriotism or populism was reflected in the college students’ comments:

“It is not about the freedom of the speech. It is about the justice and fairness of one’s comments. The higher a person’s status is, the more responsible he/she should be for his/her words. It may not be a good thing to comment on one’s backyard if one has never lived there (i.e. in China or Hong Kong), right?” (selected comment to the NBA Game news).

“I think the arena being fully seated is a matter of personal choice which cannot be attributed to …, while it is a bit inappropriate to ask the player to sign on the flag of China, as that represents the national identity” (selected comment to the NBA Game news).

From news interviews, the researchers also found that college students’ comments on news generally presented an awareness of social justice, which may represent the younger generation’s attitudes, beliefs, and values in either personal or social cognition (van Dijk, 1995 ). They emphasized objectivity and fairness over subjectivity to no small extent. For example, regarding the news of whether the NBA game tickets were refundable, the students’ comments respected the individual’s right to make decisions. Nevertheless, they also explained that it was inappropriate to sign on the flag of China. Students’ comments on the news Rayza’s airport look were even more concerned with social justice. Moreover, they analyzed the issue from an objective perspective instead of an individual perspective and extended it to the social level, which further showed that current college students are more inclined to social justice.

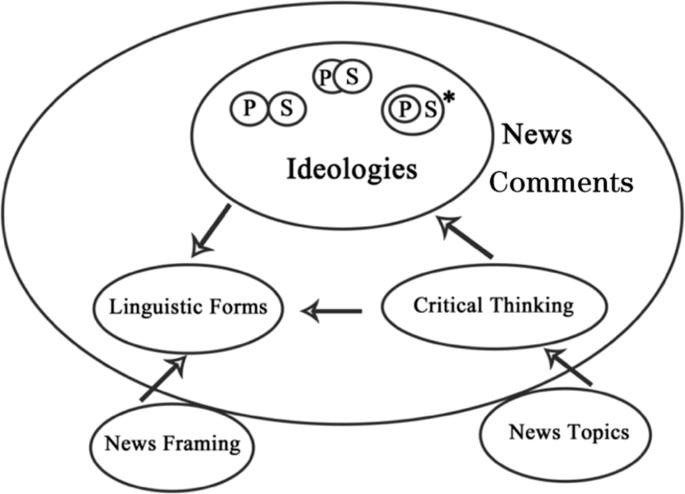

Critical thinking informing ideological and linguistic choices

One of the most important findings of this study is the complex relationships among critical thinking, ideological beliefs, and linguistic features. We present these complex relationships as shown in Fig. 1 .

*p: personal ideologies; s: social ideologies.

By mapping out different comments, we find that critical thinking works as an analytical and filtering tool to guide commenters to select their ideological beliefs, either personal or social. These personal and social ideological beliefs may diverge or converge. The divergence or convergence of personal and social ideological beliefs may indicate the strength of critical thinking, which, however, may not equal the quality of critical thinking. To be more specific, critical thinking may help commenters present a different perspective from the commonly accepted social perspective, which shows efforts in analyzing a news article and offering their opinions. However, the opinions that differ from widely accepted views may not be weighed as right or wrong or un/acceptable; they may just be different voices.

We argue that these personal and social opinions are representations of ideological beliefs and are fully presented through news comments; news comments are ideology-based. Critical thinking helps commenters choose their personal and social ideologies and then helps them choose linguistic forms they believe fit their news comments. While critical thinking plays a crucial role in choosing specific ideological beliefs and linguistic forms, news topics vary in informing commenters’ critical thinking ability. In the study, we found that some topics may inform divergence between personal and social ideological beliefs, whereas other topics may inform the convergence of the two constructs. We also propose that the way a specific piece of news is framed informs the linguistic form of the news comments, which may arouse a certain sense in the commenters (e.g., a sense of belonging as in/out-group members). Reading these news pieces may stimulate commenters’ critical thinking and then work on the linguistic forms in news comments.

The present study provided an overall account of how linguistic features, ideological beliefs, and critical thinking accounts are revealed through news comments. News comments in China present value propositions and ways of thinking through complex lexical and syntactical structures. The respondents presented power, ideology, inequality, and social justice through their responses to the news, which informed news commentary as a way to serve the social function of the language. The responses also presented the younger generation’s personal ideology through the news comments. However, topics were important in informing these constructs and caused divergences among different comments. One of the critiques that this study, and the CDA studies in general, may receive is the simplistic or even vague description of the methodology (Wodak, 2006 ) because there is currently “no accepted canon of data collection” (Wodak and Meyer, 2015 ). Instead, we tried to provide careful systemic analysis and separated description and interpretation (Wodak and Meyer, 2015 ). For future studies, we believe that further analysis of how critical thinking may work with personal and social ideologies is necessary. Additionally, it is worthwhile to study the effects of other cognitive attributes on language and ideologies to extend the SCA domain.

Data availability

The data analyzed and generated are included in the paper.

Chouliaraki L, Fairclough N (1999) Discourse in late modernity: rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Google Scholar

Fairclough N (1989) Language and power. Longman, New York

Fairclough N (1995) Media discourse. Edward Arnold, London, England

Fairclough N (2006) Language and globalization. Routledge, London

Fairclough N (2010) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. Routledge, London

Feustel R, Keller R, Schrage D, Wedl J, Wrana D, van Dyk S (2014) Zur method(olog)ischen Systematisierung der sozialwissenschaftlichen Diskurs-forschung. In: Angermüller J, et al., (eds) Diskursforschung: ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp. 482–506

Chapter Google Scholar

Halliday MAK (1978) Language as social semiotic. Edward Arnold, London

Hegel GWF (1971) Philosophy of mind: being part three of the encyclopaedia of the philosophical sciences (together with the Zusätze) (trans: Wallace W, Miller AV). Clarendon Press, Oxford

Hegel GWF (1975) Logic: being part one of the encyclopaedia of the philosophical sciences (trans: Wallace W), 3rd edn. Clarendon Press, Oxford,

Kintsch W, van Dijk TA (1978) Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cogn Psychol 6:294–323

Liu O (2019). The top 10 social media platforms in China 2018; how many do you know? Hi-com News Blog. https://www.hicom-asia.cn/top10-social-media-platforms-cn/

Marx K (1975) Contribution to the critique of Hegel’s philosophy of law. In: Marx K, Engels F (eds) Collected works, vol. 3. Progress Publishers, Moscow, pp. 3–129.

Rytina J, Loomis C (1970) Marxist dialectic and pragmatism: power as knowledge Am Sociol Rev 35(2):308–318 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2093208

Tolson A (2001) “Authentic” talk in broadcast news: the construction of community. Commun Rev 4(4):463–480

Article Google Scholar

Van Dijk TA (1991) Racism and the press. Routledge, London

Van Dijk TA (1993) Elite discourse and racism. Sage Publications. Inc, Newbury Park

Book Google Scholar

Van Dijk TA (1995) Discourse semantics and ideology. Discourse Soc 6(2):243–289

Van Dijk TA (1997) Discourse as social interaction. Sage, London

Van Dijk TA (2001) Critical discourse analysis. In: Tannen D, Schiffrin D, Hamilton H (Eds.) Handbook of discourse analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 352–371

Van Dijk TA (2006) Ideology and discourse analysis. J Political Ideol 11(2):115–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310600687908

Wodak R (2006) Mediation between discourse and society: assessing cognitive approaches in CDA. Discourse Stud 8(1):179–190

Wodak R (2007) Pragmatics and critical discourse analysis: a cross-disciplinary inquiry. Pragmat Cogn 15(1):203–225

Wodak R, Busch B (2004) Approaches to media texts. In: Downing J, McQuail D, Schlesinger P, Wartella E (eds.) Handbook of media studies. Sage, Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi, pp. 105–123

Wodak R, Meyer M (2015) Methods of critical discourse studies (3rd). Sage, London

Zienkowski J (2017) Reflexivity in the transdisciplinary field of critical discourse studies. Palgrave Commun 3:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.7

Download references

Acknowledgements

The paper is funded through Graduate Program Research Fund (# YJG2020403) at Dalian Maritime University. In addition, it is also partially funded through DMU Xinhai Scholar Research Fund (#02500805). Our sincere thanks go to our undergraduate and graduate students who were keen on helping us with data collection and analysis.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

Yang Gao & Gang Zeng

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YG made substantial contributions to the conception, design, and implementation of the work; He also drafted, revised, and finalized the work during the whole process. GZ was involved in the drafting and proofreading process of the work and also accountable for all the aspects of the work ensuring its accuracy and integrity.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yang Gao .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gao, Y., Zeng, G. Exploring linguistic features, ideologies, and critical thinking in Chinese news comments. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 39 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00715-y

Download citation

Received : 12 March 2020

Accepted : 11 January 2021

Published : 03 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00715-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Role of Critical Thinking in Professional Development of Linguists

- Conference paper

- First Online: 07 May 2020

- Cite this conference paper

- Natalia Starostina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1159-2913 10 &

- Ekaterina Sosnina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2716-1918 10

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 131))

Included in the following conference series:

- Proceedings of the Conference “Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives”

827 Accesses

1 Citations

The paper discusses the issues in developing and interaction of critical thinking competencies and personal qualities of learners enrolled in the linguistic programs at Russian universities. We focus on Critical Thinking as the universal competency of a future linguist and classify four groups of such significant qualities as cognitive, motivational, reflective and communicative ones. The authors claim that Critical Thinking is the key professional competency of a student which correlates with their professional qualities. To verify this assumption we present the series of didactic experiments with a group of 70 students and estimate interaction and development of professional qualities in the referent group of students. We have obtained the noteworthy data for the Applied Linguistics domain that demonstrate that the level of Critical Thinking has high and medium correlation with such groups of professional qualities of students as cognitive, motivational, and reflective ones, having at the same time low correlation concerning a communicative group of professional qualities of students.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Paul, R., Elder, L.: Critical Thinking Competency Standards. The Foundation for Critical Thinking, Dillon Beach (2005)

Google Scholar

Hughes J.: Critical Thinking in the Language Classroom. https://www.elionline.com/elifiles/Critical_ThinkingENG.pdf . Accessed 03 Mar 2020

Halpern, D.F.: Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. J. Gen. Educ. 50 (4), 270–286 (2001)

Article Google Scholar

Ennis, R.H.: The nature of critical thinking: an outline of critical thinking dispositions. In: 6th International Conference on Thinking, pp. 1–8. MIT Press, Cambridge (2011)

Paul, R.W.: Critical thinking: what, why, and how? New Dir. Community Coll. 77 , 3–24 (1992)

Facione, P.A.: The disposition toward critical thinking: its character, measurement, and relation to critical thinking skill. Informal Logic 20 (1), 61–84 (2000)

Tindal, G., Nolet, V.: Curriculum-based measurement in middle and high schools: critical thinking skills in content areas. Focus Except. Child. 27 (7), 1–22 (1995)

Willingham, D.T.: Critical thinking: why is it so hard to teach? Am. Educ. 31 , 8–19 (2007)

Thayer-Bacon, B.J.: Transforming Critical Thinking: Thinking Constructively. Teachers College Press, New York (2000)

Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J.R., Daniels, L.B.: Conceptualizing critical thinking. J. Curriculum Stud. 31 (3), 285–302 (1999)

Facione, P.: American Philosophical Association [APA] critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. The Delphi Report: Research Findings and Recommendations Prepared for the Committee on Pre-college Philosophy. California Academic Press, Fullerton (1990)

Negrete, J.: The use of problem-solving tasks to promote critical thinking skills in intermediate english level students. Rev. Palabra 5 (1), 48–55 (2016)

Nada, E.S., Beng, H.S.: Does explicit teaching of critical thinking improve critical thinking skills of English language learners in higher education? A critical review of causal evidence. Stud. Educ. Eval. 60 , 140–162 (2019)

Yufrizal, H.: Enhancing critical thinking through calla in developing writing ability of EFL students. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 6 (11), 302–313 (2019)

Mehdi, D., Mohammad, S.: EFL teachers’ learning and teaching beliefs: does critical thinking make a difference? Int. J. Instr. 11 (4), 223–240 (2018)

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Şeker, H., Kömür, S.: The relationship between critical thinking skills and in-class questioning behaviours of English language teaching students. Eur. J. Teacher Educ. 31 (4), 389–402 (2008)

Thinking Skills Assessment Test for the University of Oxford. https://www.admissionstesting.org/for-test-takers/thinking-skills-assessment/tsa¬oxford/preparing-for-tsa-oxford/ . Accessed 01 Dec 2019

Morossanova, V.I.: Extraversion and neiroticism: the typical profiles of self-regulation. Eur. Psychol. 4 , 279–288 (2003)

Thomas, K.W.: Conflict and conflict management. In: Dunnette, M.D. (ed.) Handbook in Industrial and Organizational Psychology, pp. 889–935. Rand McNally, Chicago (1976)

Schuller, I.S., Comunian, A.L.: Cross-cultural comparison of arousability and optimism scale (AOS). In: 18th International Conference of Stress and Anxiety Research Society, pp. 457–460. Dusseldorf University Press, Dusseldorf (1999)

Ilyin, E.P.: Psikhologiya voli (Psychology of Volition), 2nd edn. Piter, St. Petersburg (2009). (in Russian)

Ilyin, E.P.: Motivatsiya i motivy (Motivation and Motives). Piter, St. Petersburg (2000). (in Russian)

Temple, C., Steele, J., Meredith, K.: RWCT Project: Reading, Writing, Discussion in Every Discipline: Guidebook III. International Reading Association for RWCT, Washington (1996)

Sosnina, E.: Support of blended learning in domain-specific translation studies. In: ICERI 2018 Proceedings, pp. 5112–5116. IATED, Seville (2018). (in Russian)

Dalgaard, P.: Introductory Statistics with R, 2nd edn. Springer, New York (2008)

Book Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgments

In 2019, the discussed research of our group was supported by the Fond of Fundamental Research of the Russian Federation (RFFI state grant N 18-413-730018/19).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ulyanovsk State Technical University, Ulyanovsk, 432027, Russia

Natalia Starostina & Ekaterina Sosnina

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ekaterina Sosnina .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Research Centre Kairos, Tomsk, Russia

Zhanna Anikina

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Starostina, N., Sosnina, E. (2020). The Role of Critical Thinking in Professional Development of Linguists. In: Anikina, Z. (eds) Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives. IEEHGIP 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 131. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47415-7_82

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47415-7_82

Published : 07 May 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-47414-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-47415-7

eBook Packages : Intelligent Technologies and Robotics Intelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Teaching and Assessing Critical Thinking in Second Language Writing: An Infusion Approach

Dong Yanning holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia. She is currently vice president of Higher English Education Publishing at Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. Her research focuses on teaching English as a second language, second language writing and critical thinking.

Recent calls for promoting students’ critical thinking (CT) abilities leave second language (L2) teachers wondering how to integrate CT into their existing agenda. Framed by Paul and Elder’s (2001) CT model, the study explores how CT could be effectively taught in L2 writing as a way to improve students’ CT skills and L2 writing performance. In this study, an infusion approach was developed and implemented in actual classroom teaching. Mixed methods were employed to investigate: (1) the effectiveness of the infusion approach on improving students’ CT and L2 writing scores; (2) the relationship between students’ CT and L2 writing scores; and (3) the effects of the infusion approach on students’ learning of CT and L2 writing. The results of the statistical analyses indicate that the infusion approach has effectively improved students’ CT and L2 writing scores and that there was a significant positive relationship ( r =0.893, p <0.01) between students’ CT and L2 writing scores. The results of the post-study interview illustrate that the infusion approach has beneficial effects on students’ learning of CT and L2 writing by bridging the abstract CT theories and interactive writing activities and by integrating the instruction and practice of CT into those of L2 writing.

About the author

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research , 78 (4), 1102-1134. 10.3102/0034654308326084 Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Search in Google Scholar

Bailin, S., & Siegel, H. (2003). Critical thinking. In N. Blake, P. Smeyers, R. Smith, & P. Standish (Eds.), The Blackwell guide to the philosophy of education (pp. 181-193). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Search in Google Scholar

Bean, J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Search in Google Scholar

Beyer, B. K. (2008). How to teach thinking skills in social studies and history. The Social Studies , 99 (5), 196-201. 10.3200/TSSS.99.5.196-201 Search in Google Scholar

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Committee of college and university examiners: Handbook 1 cognitive domain . New York, NY: David McKay Company, Inc. Search in Google Scholar

Cambridge ESOL. (2011). Cambridge IELTS 8 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Case, R. (2005). Moving critical thinking to the main stage. Education Canada , 45 (2), 45-49. Search in Google Scholar