Eureka Sheets

- Teaching the Setting of A Story: Ideas, Activities & Freebies

Teaching the setting of a story is oftentimes simplified to just identifying the time and place of a story. However, there are more activities we can do when teaching the setting of a story.

This post is a summary or guide of all the setting-related posts I shared before. Here, you will find some FREE ideas, worksheets, or activities that will help students learn about the plot of a story.

Teaching the Setting Activities & Freebies

Free ppt mini-lesson.

This free resource includes various types of practice to help students grasp the “analyzing setting” reading skill.

Students will practice how to identify the setting, describe the setting, analyze the setting, and finally write about the setting.

It’s differentiated as each type of question provides different levels of support. Use it to teach your mini-lesson, or assign students questions that meet their needs for independent practice. Read more.

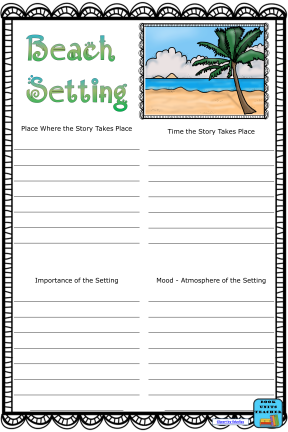

Free Graphic Organizers

These three differentiated setting graphic organizers can help students study the setting while reading texts at their own reading levels.

They are for texts at different levels of complexity. You may use these graphic organizers together for different groups in one lesson. Or you may use them as a progression for the same group of students. Read more .

Free & Differentiated Worksheets

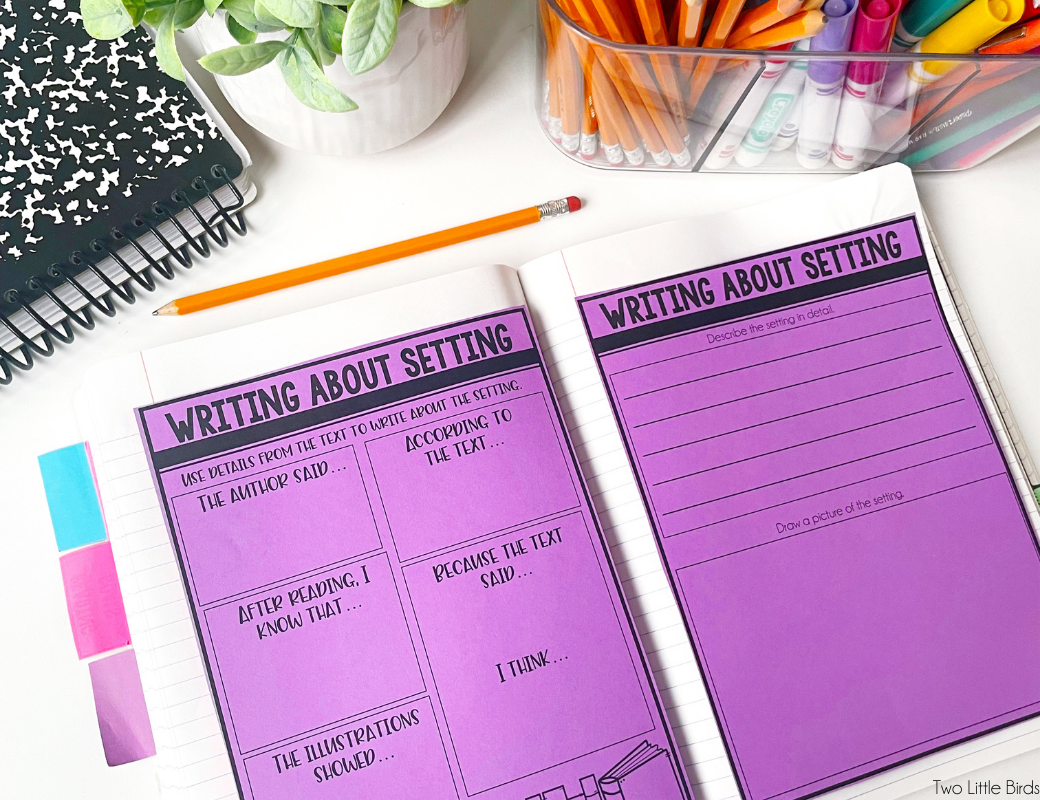

This freebie includes three worksheets for students to practice identifying, describing, and writing about the setting of a story.

It also provides the answer key to all the questions except the writing questions.

You can simply follow the progression and make your own worksheets for your students, or save your planning time by getting the freebie or the product. Read more.

36 Differentiated Task Cards

Task cards are one of my favorite activities. They are super flexible to use, so students can learn effectively during the sporadic time, such as transitions, small group time, etc.

You may also use them as exit tickets, etc. You never run out of ways of using them!

There are three types of task cards: 1. Identify the setting of a story; 2. Describe the setting of a story; 3. Write About the Setting of a Story. Read more.

These setting-related posts above provide free ideas, worksheets, or activities you may use to teach the setting of a story to your elementary students, especially 2nd to 5th graders. For other grades, simply proofread or modify them to suit your class before your lesson.

Teaching the Setting Products

If you find some of them are helpful and want more, you may check and purchase the corresponding products in my store.

If you want to save your prep time and money at the same time! Here, this bundle will be a great choice for you. It includes ready-to-teach PPT/Google Slides, differentiated worksheets, graphic organizers, and task cards.

However, if you want to save, I promise more posts of ideas and freebies are coming your way! Just sign up for our newsletter below, so you won’t miss any new updates or freebies!

Other Reading Skills:

- Teaching the Plot of A Story: Ideas, Activities & Freebies

- Gist Activities to Improve Comprehension

- HOW IT WORKS

- INSTITUTIONAL SALES

Want 20% off your first purchase?

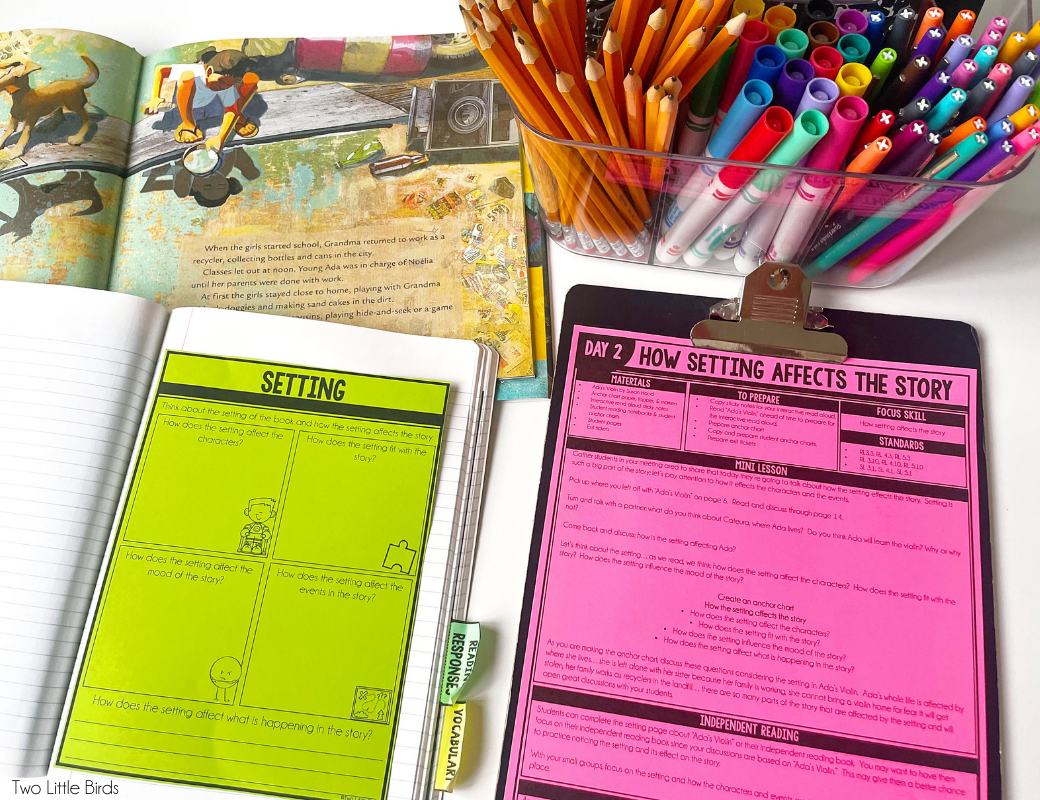

5 ways to teach setting and engage your students.

When reading a story, one of the most important aspects is the setting. It is oftentimes overlooked by students as they tend to focus more on the characters or the plot. The setting can help to create the mood and tone of the story. It can also help to engage your students in their reading as the setting truly affects every other part of the story.

The setting influences the characters and their personalities and affects the plot in many ways. The setting provides a place for the characters to create their stories and it helps strengthen students' understanding of the other story elements.

For students to completely understand the characters and events in a story, they must understand the importance that the setting plays. The setting can affect the characters internally and externally. The setting can help set the mood or the feeling in the story and help students make connections. Students learn to pay attention to the “when” and “where” as they read and make inferences about the text.

Here are 5 lessons to teach when you are helping students understand the importance of the setting in a story:

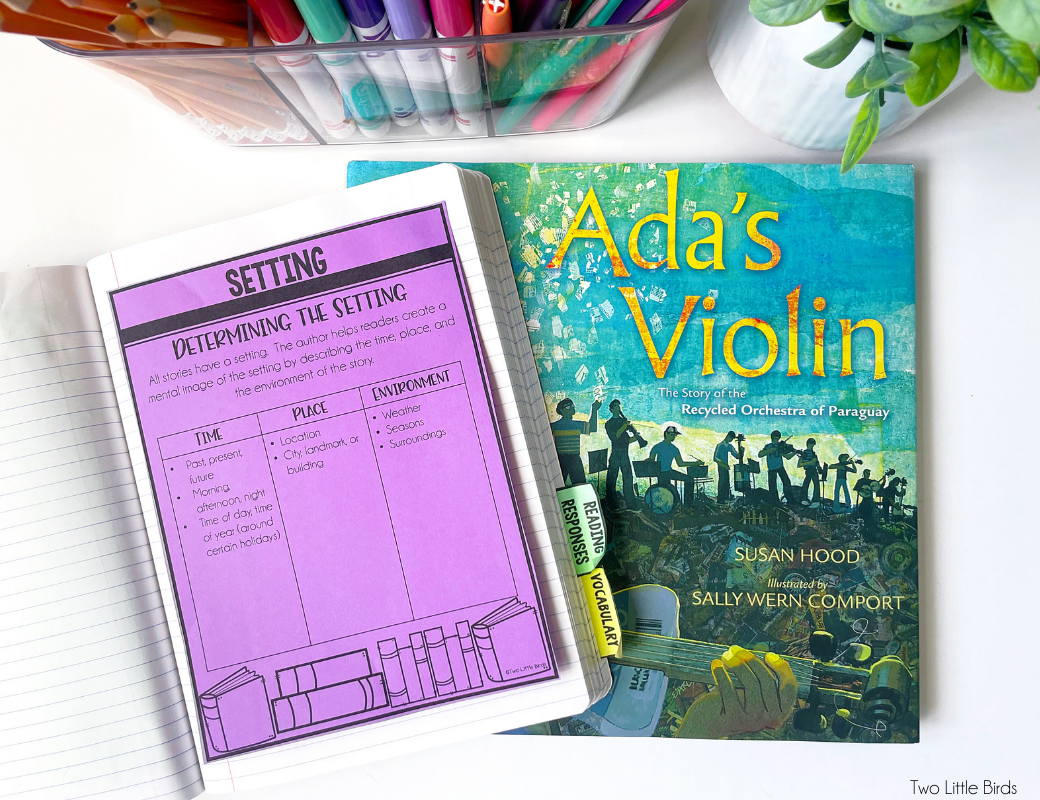

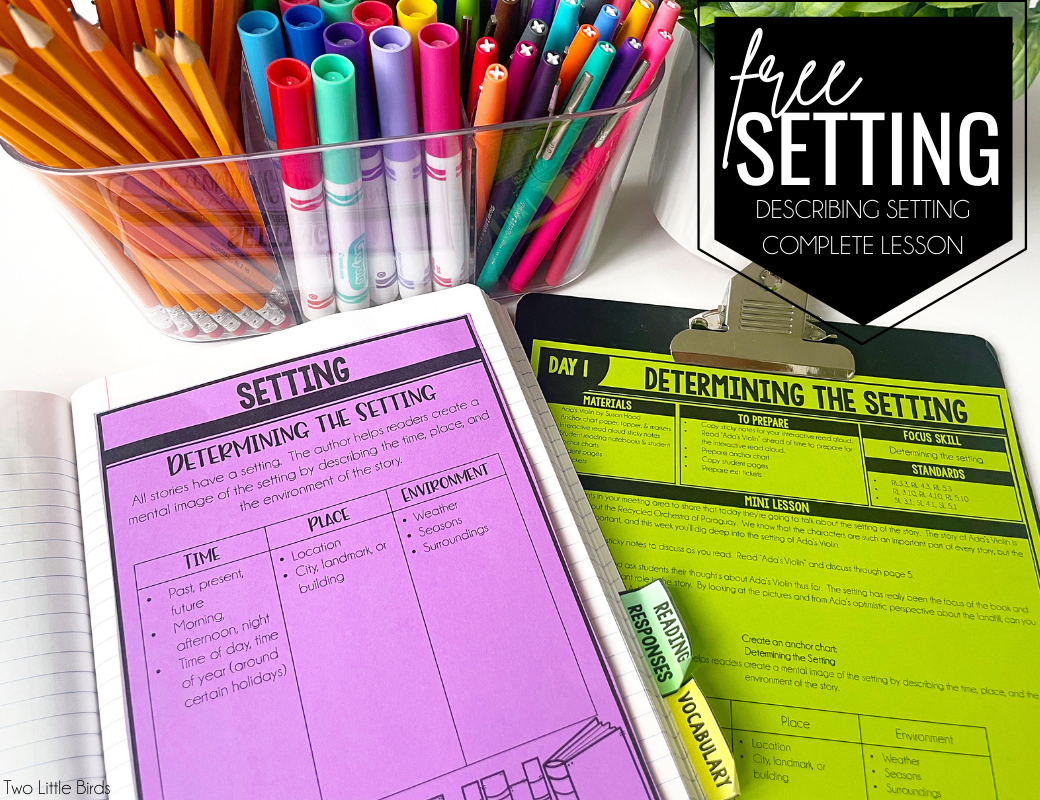

1. Determining the Setting

One of the most important things you'll want to do as a teacher when helping students understand the setting is to help them determine where and when the story is taking place. This can be done by asking questions such as:

- What does the environment look like?

- What type of weather is happening?

- Are there any specific holidays or events happening?

- What year is it?

- Is it during the day or at night?

Once you've helped students understand where and when the story is taking place, they'll be better able to visualize the story and understand how it affects the characters and plot.

2. How the Setting Can Affect the Story:

The setting is more than just the location and time of a story. It can also affect the plot and characters in many ways. For example, if the story is set in a cold environment, the characters might be forced to stay inside and deal with their problems, as opposed to going on an adventure. Or, if the story is set in a hot environment, the characters might be constantly dealing with things like dehydration or sunburn.

In addition to the physical setting, it's important to understand the social setting of a story. This includes everything from the culture of the characters to the laws and customs that are in place. Teaching students about the social setting can help them better understand why characters behave in certain ways and make the decisions that they do.

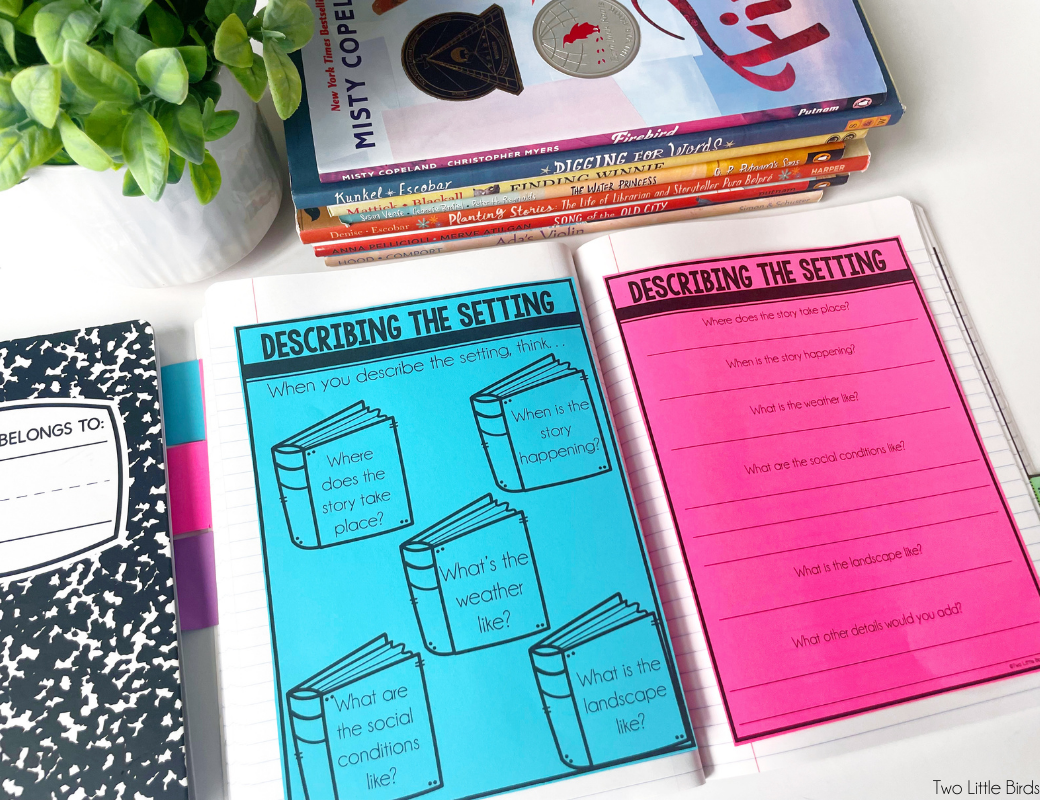

3. Describing the Setting:

One of the best ways to help students understand the setting is to have them describe the setting with words. Ask them to think about what the weather is like, what the landscape looks like, what the people in the setting are wearing, and what the social conditions look like. You can also ask them to describe the emotions that the setting elicits. For example, if a story is set in a cold environment, the students might feel tense because of the chilly weather.

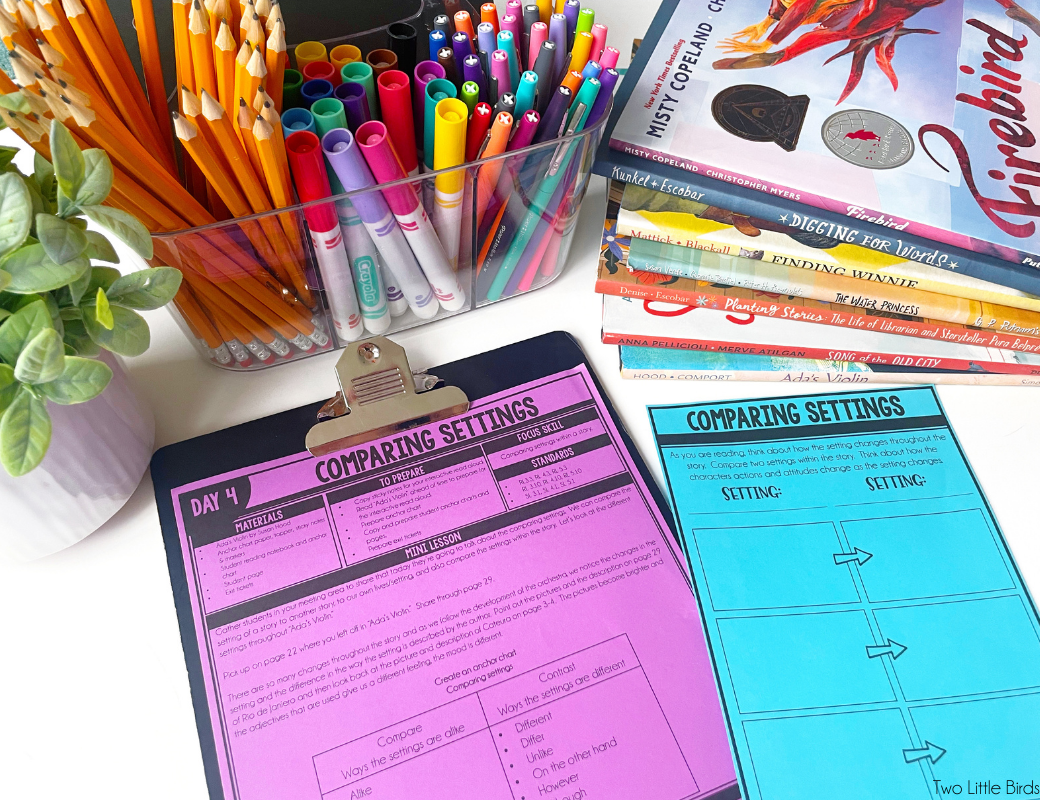

4. Comparing Settings:

One way to help students understand the importance of setting is to have them compare and contrast different settings. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as writing about the setting, creating charts or diagrams, or even acting out scenes from different stories.

By comparing and contrasting different settings, students can see how the setting can affect the plot, characters, and overall tone of a story. For example, if you are comparing a story that is set in the city with one that is set in the country, you might want to focus on things like:

- The environment (urban vs. rural)

- The culture (sophisticated vs. simple)

- The social dynamics (close-knit community vs. anonymous city)

- The physical surroundings (tall buildings vs. wide open spaces)

Comparing and contrasting settings can help students develop a deeper understanding of what makes a story unique and interesting. It can also help them better appreciate the role that the setting plays in shaping a story.

5. Writing About the Setting:

When writing about the setting of a story, it can be helpful to think about the following questions:

- What is the most important thing about the setting in relation to the story?

- What is the mood or feeling that the setting evokes?

- How does the setting help to create the tone of the story?

When a story is set in more than one location, it can add an extra layer of complexity to the plot. For example, a story might take place in both the present and the past, or in two different parts of the world. By comparing and contrasting the different settings, students can get a better sense of how each location affects the characters and the overall story.

In order to help students understand multiple settings, you can use graphic organizers like Venn diagrams or chart paper. You can also have students create their own maps or illustrations that show the different locations in the story.

Teaching setting is an important part of helping students understand the elements of a story. Teaching about the setting can help students better understand not only the stories they are reading but also their own lives. What are some ways that you have helped your students understand the setting in a story?

Shop the resources featured in this post:

Happy Teaching!

You may also enjoy:.

Creating Lifelong Readers With Interactive Read Alouds

Teaching Character Traits with Graphic Organizers

The Plot Development Roller Coaster

Activities for Teaching Setting of a Story

- By Gay Miller in Literacy

April 5, 2021

The setting of a story includes the time and location in which the story takes place. Most students can easily say this story takes place at the beach or the moon or Alaska or wherever. Many students can also pinpoint the time: the past, present, or future. However, often students do not realize that the setting also provides important clues to the plot.

Information to Use in Classroom Discussions

Setting and attitude.

Where characters live often contributes to their personalities. Different settings influence a character’s values or attitude.

Think of these examples:

- Would The Watsons go to Birmingham – 1963 be the same story if it had been set anywhere but the 1960s American South?

- Could Sweep: The Girl and her Monster be set at any time other than Victorian England where children were allowed to climb inside chimneys to clean?

- Would Jonah from The Giver be made the receiver of memories in any setting except for a dystopian future?

- Add examples from the novels your students have read.

Get all handouts and activities for the setting of a story post here.

The setting of a story and conflict.

In many novels, the setting causes the conflict of the story.

- If Brian had reached his father in the oil fields instead of crash landing in the middle of the Canadian wilderness in the novel Hatchet , would Gary Paulsen be telling the reader a survival story?

- Would Sadako from Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes be faced with leukemia if she didn’t live in 1955 Hiroshima, Japan?

- If Naya from A Long Walk to Water didn’t live in Southern Sudan, would she spend her days traveling back and forth to the water hole?

FREE Teaching Ideas and Printables for Teaching Setting

Activity #1 anchor charts for setting of a story.

Grab these free “Printable Charts for Setting” in the blog post handout. Print the charts on standard 11 by 8.5-inch paper or poster size for classroom display. On the charts, students list the location, time, importance, and mood of the setting. The chart may be used for any story. Printing instructions are included in the handout.

Get all handouts from this post including these posters here.

This blank setting anchor chart is editable. It will download as a PowerPoint. If you would like to keep the same font that says, “Setting,” click anywhere next to the word setting in the text box and just start typing. Delete the old text AFTER you have your new text completed.

Activity #2 – Setting and Time

The time is when the story happens. It may be in the past, present, or future. The time may also be an event such as during the Great War. Time greatly influences the plot of the story.

Use this link to get this activity. Students match definitions to terms related to the setting. Both printable and digital versions are included.

Get all activities from this post here.

- The Clock…Waiting – When characters must wait for an event to take place several things can happen. Suspense has the reader on edge if the event is something such as the police locating a bomb. Anticipation can build if the character is waiting for something exciting to happen such as the big game or contest.

- Seasons – Little Willy’s race in Stone Fox could only take place in the winter when the ground was snow-covered. Novels such as Because of Mr. Terupt , Schooled , Wonder , and There’s a Boy in the Girls’ Bathroom could only take place during the school year. Evan and Jessie from The Lemonade War would not have successful lemonade stands if it was not the hot part of the summer.

- Historical Time – Authors writing historical fiction must set the stories not only where and when the historical event took place but must remember the other differences of the era. Time has changed the way people speak and think. Authors incorporate slang, social behaviors, and practices of the time when writing historical fiction.

Activity #3 – Video Lessons for Setting of a Story

Activity #4 – Setting and Place

T he setting doesn’t have to be real-time and place. It can be imaginary…a magical kingdom, the mythical city of Atlantis, or inhabited planets in distant universes.

The place may include the geographic locat ion such as the Ozark Mountains and specific sites such as Billy’s house.

Good authors use vivid imagery to describe the setting including the “Show, Don’t Tell” concept. Use a chart like this to have students locate and write sensory details.

The activity pictured here is in the handout.

Activity #5 – Setting and Genre

The genre of a story often dictates the setting. Look at these examples.

Science Fiction >> Outer Space >> Future

Fairy Tales >> Magical Kingdom >> Usually Past

Realistic Fiction >> Real Locations >> Usually Present

Myth >> Heaven and Earth >> Past

Historical Fiction >> Real Location >> Past

Activity #6 – Clues to the Setting

Ways the setting is revealed include:

- by dialogue between characters

- with descriptive passages

- through action

- by how the characters speak or act

Click on these buttons to go to other posts in this series.

- Story Elements

Permanent link to this article: https://bookunitsteacher.com/wp/?p=405

- Jenny on July 29, 2015 at 7:29 am

Incredible points. Solid arguments. Keep up the great spirit.

- Celina on August 1, 2015 at 7:41 pm

WOW just what I was looking for.

Comments have been disabled.

Click on the button below to follow this blog on Bloglovin’.

Clipart Credits

Caboose Designs

Teaching in the Tongass

Chirp Graphics

Sarah Pecorino Illustration

© 2024 Book Units Teacher.

Made with by Graphene Themes .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Writing Techniques

How to Teach Creative Writing

Last Updated: March 13, 2024 References

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 117,240 times.

Creative writing is one of the most enjoyable types of writing for students. Not only does it allow students to explore their imaginations, but it helps them to structure their ideas and produce writing that they can be proud of. However, creative writing is a relatively difficult type of writing to teach and offers challenges to both new and seasoned teachers alike. Fortunately, though, with some work of their own, teachers can better develop their own abilities to teach creative writing.

Providing Students with the Fundamentals

- Theme. The theme of a story is its message or the main idea behind it.

- Setting. The setting of a story is the location or time it takes place in.

- Plot. The plot is the overall story, narrative, or sequence of events.

- Characterization. Characterization is how a character or person in a story is explained or presented to the reader.

- Conflict and dramatic action. Conflict and dramatic action are the main events of focus in the story. These events are often tense or exciting and are used to lure the reader in. [1] X Research source

- Explain how your students, as writers, can appeal to the humanity of their readers. One great way to do this is to ask them to explore character development. By developing the characters in their story, readers will become invested in the story.

- Discuss the triggers that engage readers in an effective story. Most great stories start with a problem, which is solved with the resolution, or conclusion of the story. Encourage students to create an engaging problem that will hook the readers in the first few pages of a short story or novel. [2] X Research source

- By setting the tone and atmosphere of a story, the author will establish his or her attitude to the subject and the feel of the story.

- Tone can be positive, neutral, or negative. [3] X Research source

- Atmosphere can be dark, happy, or neither.

- Descriptive words like “darkness” or “sunshine” can help set both the tone and atmosphere. [4] X Research source

- Active verbs are used to show action in the story.

- Active verbs are very often a better alternative to passive voice, as it keeps your writing clear and concise for your readers. [5] X Research source

- For example, instead of writing “The cat was chased by the dog” your student can write “The dog chased the cat.”

Guiding Students through the Process

- Tell your students to brainstorm about ideas they are truly interested in.

- If you must restrict the general topic, make sure that your students have a good amount of wiggle room within the broad topic of the assignment.

- Never assign specific topics and force students to write. This will undermine the entire process. [6] X Research source

- Letting your students know that the outline is non-binding. They don’t have to follow it in later steps of the writing process.

- Telling your students that the parts of their outline should be written very generally.

- Recommending that your students create several outlines, or outlines that go in different directions (in terms of plot and other elements of storytelling). The more avenues your students explore, the better. [7] X Research source

- Tell students that there is no “right” way to write a story.

- Let students know that their imaginations should guide their way.

- Show students examples of famous writing that breaks normal patterns, like the works of E.E. Cummings, William Faulkner, Charles Dickens, and William Shakespeare.

- Ask students to forget about any expectations they think you have for how a story should be written. [8] X Research source

- Gather the first drafts and comment on the student's work. For first drafts, you want to check on the overall structure of the draft, proper word use, punctuation, spelling, and overall cohesion of the piece. [9] X Research source

- Remind them that great writers usually wrote several drafts before they were happy with their stories.

- Avoid grading drafts for anything other than completion.

- Let students pair off to edit each others' papers.

- Have your students join groups of 3 or 4 and ask them to go edit and provide feedback on each member’s story.

- Provide guidance so students contribute constructively to the group discussion. [10] X Research source

- Reward your students if they are innovative or do something unique and truly creative.

- Avoid evaluating your students based on a formula.

- Assess and review your own standards as often as you can. Remember that the point is to encourage your students' creativity. [11] X Research source

Spurring Creativity

- Teach your students about a variety of writers and genres.

- Have your students read examples of different genres.

- Promote a discussion within your class of the importance of studying literature.

- Ask students to consider the many ways literature improves the world and asks individuals to think about their own lives. [12] X Research source

- Make sure your room is stocked with a wide variety of fiction stories.

- Make sure your room is stocked with plenty of paper for your students to write on.

- Line up other writing teachers or bring in writers from the community to talk to and encourage your students.

- Cut out pictures and photographs from magazines, comic books, and newspapers.

- Have your students cut out photographs and pictures and contribute them to your bank.

- Consider having your students randomly draw a given number of photos and pictures and writing a short story based on what they draw.

- This technique can help students overcome writer's block and inspire students who think that they're "not creative." [13] X Research source

- Pair your students with students from another grade in your school.

- Allow your students to write stories that younger students in your school would like to read.

- Pair your students with another student in the class and have them evaluate each others' work. [14] X Research source

- If you just have a typical classroom to work with, make sure to put inspirational posters or other pictures on the walls.

- Open any curtains so students can see outside.

- If you have the luxury of having an extra classroom or subdividing your own classroom, create a comfortable space with a lot of inspirational visuals.

- Writing spaces can help break writer's block and inspire students who think that they're "not creative." [15] X Research source

- Involve students in the printing process.

- Publication does not have to be expensive or glossy.

- Copies can be made in the school workroom if possible or each student might provide a copy for the others in the group.

- A collection of the stories can be bound with a simple stapler or brads.

- Seek out other opportunities for your students to publish their stories.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.writersonlineworkshops.com/courses/creative-writing-101

- ↑ https://kobowritinglife.com/2012/10/14/six-tips-for-engaging-readers-within-two-seconds-the-hook-in-fiction-and-memoir/

- ↑ https://www.dailywritingtips.com/in-writing-tone-is-the-author%E2%80%99s-attitude/

- ↑ http://ourenglishclass.net/class-notes/writing/the-writing-process/craft/tone-and-mood/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/539/02/

- ↑ http://www.alfiekohn.org/article/choices-children/

- ↑ https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/7-steps-to-creating-a-flexible-outline-for-any-story

- ↑ http://thewritepractice.com/the-formula-to-write-a-novel/

- ↑ https://student.unsw.edu.au/editing-your-essay

- ↑ http://orelt.col.org/module/unit/5-promoting-creative-writing

- ↑ http://education.seattlepi.com/grade-creative-writing-paper-3698.html

- ↑ http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/04/educating-teenagers-emotions-through-literature/476790/

- ↑ http://www.wrightingwords.com/for-teachers/5-tips-for-teaching-creative-writing/

About This Article

To teach creative writing, start by introducing your students to the core elements of storytelling, like theme, setting, and plot, while reminding them that there’s no formula for combining these elements to create a story. Additionally, explain how important it is to use tone and atmosphere, along with active verbs, to write compelling stories that come alive. When your students have chosen their topics, have them create story outlines before they begin writing. Then, read their rough drafts and provide feedback to keep them on the right path to storytelling success. For tips from our English reviewer on how to spur creativity in your students, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Yunzhe Yang

Mar 27, 2017

Did this article help you?

Daniel Hesse

Dec 5, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Inspiring Ink: Expert Tips on How to Teach Creative Writing

The world of creative writing is as vast as it is rewarding. It’s a form of expression that allows the writer to explore different worlds, characters, and narratives – all within the power of their pen.

But what exactly is creative writing and why is it important? Let’s explore the value of creative writing and how to inspire young (or old!) minds to embark on the curious and exciting journey of writing creatively – it’s easier than you think!

What is Creative Writing?

Creative writing, in its simplest form, is writing that goes beyond the bounds of normal professional, journalistic, academic, or technical forms of literature.

It’s characterized by its emphasis on:

- narrative craft

- character development

- the use of literary devices

From poetry to plays, scripts to sonnets, creative writing covers a wide range of genres . It’s about painting pictures with words, invoking emotions, and bringing ideas to life . It’s about crafting stories that are compelling, engaging, and thought-provoking.

Whether you’re penning a novel or jotting down a journal entry, creative writing encourages you to unleash your imagination and express your thoughts in a unique, artistic way. For a deeper dive into the realm of creative writing, you can visit our article on what is creative writing .

Benefits of Developing Creative Writing Skills

The benefits of creative writing extend beyond the page.

It’s not just about creating captivating stories or crafting beautiful prose. The skills developed through creative writing are invaluable in many aspects of life and work.

1. Creative writing fosters creativity and imagination.

It encourages you to think outside the box, broaden your perspective, and explore new ideas. It also enhances your ability to communicate effectively, as it involves conveying thoughts, emotions, and narratives in a clear and compelling manner.

2. Creative writing aids in improving critical thinking skills.

It prompts you to analyze characters, plotlines, and themes, and make connections between different ideas. This process activates different parts of the mind, drawing on personal experiences, the imagination, logical plot development, and emotional intelligence.

3. Creative writing is also a valuable tool for self-expression and personal growth.

It allows you to explore your feelings, experiences, and observations, providing an outlet for self-reflection and introspection. By both reading and writing about different characters in different situations, readers develop empathy in a gentle but effective way.

4. Creative writing skills can open up a host of career opportunities.

From authors and editors to content creators and copywriters, the demand for creative writers is vast and varied. You can learn more about potential career paths in our article on creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree .

In essence, creative writing is more than just an art—it’s a skill, a craft, and a powerful tool for communication and self-expression. Whether you’re teaching creative writing or learning it, understanding its value is the first step towards mastering the art.

The 3 Roles of a Creative Writing Teacher

Amongst the many facets of a creative writing teacher’s role, three vital aspects stand out: inspiring creativity , nurturing talent , and providing constructive criticism . These elements play a significant role in shaping budding writers and fostering their passion for the craft.

1. Inspiring Creativity

The primary function of a creative writing teacher is to inspire creativity.

They must foster an environment that encourages students to think outside the box and explore new possibilities . This includes presenting students with creative writing prompts that challenge their thinking, promoting lively discussions around various topics, and providing opportunities for students to engage in creative writing activities for kids .

Teachers should also expose students to a range of literary genres , styles, and techniques to broaden their understanding and appreciation of the craft. This exposure not only enhances their knowledge but also stimulates their creativity, encouraging them to experiment with different writing styles .

2. Nurturing Talent

Nurturing talent involves recognizing the unique abilities of each student and providing the necessary support and guidance to help them develop these skills. A creative writing teacher needs to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each student and tailor their approach accordingly.

This means:

- offering personalized feedback

- setting realistic yet challenging goals

- providing opportunities for students to showcase their work

Encouraging students to participate in writing competitions or to publish their work can give them a confidence boost and motivate them to improve. Furthermore, teachers should educate students about various creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree . This knowledge can inspire students to pursue their passion for writing and explore career opportunities in the field.

3. Providing Constructive Criticism

Providing constructive criticism is a critical aspect of teaching creative writing. It involves assessing students’ work objectively and providing feedback that helps them improve .

Teachers should:

- highlight the strengths of the work

- address the areas that need improvement

- suggest ways to make the piece better

Constructive criticism should be specific, actionable, and encouraging . It’s important to remember that the goal is to help the student improve, not to discourage them. Therefore, teachers need to communicate their feedback in a respectful and supportive manner.

In essence, a teacher’s role in teaching creative writing extends beyond mere instruction. They are mentors who inspire, nurture, and shape the minds of budding writers. By fostering a supportive and stimulating environment, they can help students unlock their creative potential and develop a lifelong love for writing.

3 Techniques for Teaching Creative Writing

When it comes to understanding how to teach creative writing, there are several effective techniques that can help inspire students and foster their writing skills.

1. Encouraging Free Writing Exercises

Free writing is a technique that encourages students to write continuously for a set amount of time without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or topic. This type of exercise can help unleash creativity, as it allows students to freely express their thoughts and ideas without judgment or constraint.

As a teacher, you can set a specific theme or provide creative writing prompts to guide the writing session. Alternatively, you can allow students to write about any topic that comes to mind. The key is to create an environment that encourages creative exploration and expression.

2. Exploring Different Genres

Another effective technique is to expose students to a wide range of writing genres. This can include fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, fantasy, mystery, and more. By exploring different genres, students can discover their unique writing styles and interests. This variety also offers the chance to expand their writing skills and apply them to various writing formats.

To facilitate this exploration, you can assign writing projects in different genres, conduct genre-specific writing workshops, or invite guest speakers who specialize in different genres. You can also encourage students to critically analyze how different authors approach their work.

3. Analyzing Published Works

Analyzing published works is a powerful way to teach creative writing. This technique allows students to learn from established authors by studying their:

- writing styles

- narrative structures

- use of language.

It also provides a practical context for understanding writing concepts and techniques.

As a teacher, you can select diverse pieces of literature for analysis , ranging from classic novels to contemporary short stories. Encourage students to identify elements they admire in these works and discuss how they can incorporate similar techniques into their own writing.

These techniques for teaching creative writing are effective ways to inspire creativity, encourage self-expression, and develop writing skills. As a teacher, your role is crucial in guiding students through their creative journey and helping them realize their potential as writers.

Creative Writing Workshops and Exercises

One effective method on how to teach creative writing is through the use of targeted workshops and exercises. These interactive sessions can stimulate creativity, foster character development , and help in understanding story structures .

Idea Generation Workshops

Idea generation is a crucial aspect of creative writing. It is the starting point that provides a springboard for writers to explore and develop their narratives. Idea generation workshops can be an interactive and fun way to help writers come up with fresh ideas.

Workshops can include brainstorming sessions , where writers are encouraged to think freely and note down all ideas, no matter how unconventional they may seem. Another method is the use of writing prompts , which can serve as a creative spark.

A prompt could be:

- even an image

Editor’s Note : Encourage children to create a big scribble on a scrap piece of paper and then look for an image in it (like looking for pictures in the clouds). This can be a great creative writing prompt and students will love sharing their writing with each other! Expect lots of giggles and fun!

Character Development Exercises

Characters are the heart of any story. They drive the narrative and engage the readers. Character development exercises can help writers create well-rounded and relatable characters.

Such exercises can include character questionnaires , where writers answer a series of questions about their characters to gain a deeper understanding of their personalities, backgrounds, and motivations. Role-playing activities can also be useful, allowing writers to step into their characters’ shoes and explore their reactions in different scenarios.

Story Structure Workshops

Understanding story structure is vital for creating a compelling narrative. Story structure workshops can guide writers on how to effectively structure their stories to engage readers from start to finish .

These workshops can cover essential elements of story structures like:

- rising action

- falling action

In addition to understanding the basics, writers should be encouraged to experiment with different story structures to find what works best for their narrative style. An understanding of story structure can also help in analyzing and learning from published works .

Providing writers with the right tools and techniques, through workshops and exercises, can significantly improve their creative writing skills. It’s important to remember that creativity flourishes with practice and patience .

As a teacher, nurturing this process is one of the most rewarding aspects of teaching creative writing. For more insights and tips on teaching creative writing, continue exploring our articles on creative writing .

Tips to Enhance Creative Writing Skills

The process of teaching creative writing is as much about honing one’s own skills as it is about imparting knowledge to others. Here are some key strategies that can help in enhancing your creative writing abilities and make your teaching methods more effective.

Regular Practice

Like any other skill, creative writing requires regular practice . Foster the habit of writing daily, even if it’s just a few lines. This will help you stay in touch with your creative side and continually improve your writing skills. Encourage your students to do the same.

Introduce them to various creative writing prompts to stimulate their imagination and make their writing practice more engaging.

Reading Widely

Reading is an essential part of becoming a better writer. By reading widely, you expose yourself to a variety of styles, tones, and genres . This not only broadens your literary horizons but also provides a wealth of ideas for your own writing.

Encourage your students to read extensively as well. Analyzing and discussing different works can be an excellent learning exercise and can spark creative ideas .

Exploring Various Writing Styles

The beauty of creative writing lies in its diversity. From poetic verses to gripping narratives, there’s a wide range of styles to explore. Encourage your students to try their hand at different forms of writing. This not only enhances their versatility but also helps them discover their unique voice as a writer.

To help them get started, you can introduce a variety of creative writing activities for kids . These tasks can be tailored to suit different age groups and proficiency levels. Remember, the goal is to foster a love for writing, so keep the activities fun and engaging .

Have Fun Teaching Creative Writing!

Enhancing creative writing skills is a continuous journey. It requires persistence, curiosity, and a willingness to step out of your comfort zone. As a teacher, your role is to guide your students on this journey, providing them with the tools and encouragement they need to flourish as writers – and most of all – enjoy the process!

For more insights on creative writing, be sure to explore our articles on what is creative writing and creative writing jobs and what you can do with a creative writing degree .

Brooks Manley

Creative Primer is a resource on all things journaling, creativity, and productivity. We’ll help you produce better ideas, get more done, and live a more effective life.

My name is Brooks. I do a ton of journaling, like to think I’m a creative (jury’s out), and spend a lot of time thinking about productivity. I hope these resources and product recommendations serve you well. Reach out if you ever want to chat or let me know about a journal I need to check out!

Here’s my favorite journal for 2024:

Gratitude Journal Prompts Mindfulness Journal Prompts Journal Prompts for Anxiety Reflective Journal Prompts Healing Journal Prompts Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Journal Prompts Mental Health Journal Prompts ASMR Journal Prompts Manifestation Journal Prompts Self-Care Journal Prompts Morning Journal Prompts Evening Journal Prompts Self-Improvement Journal Prompts Creative Writing Journal Prompts Dream Journal Prompts Relationship Journal Prompts "What If" Journal Prompts New Year Journal Prompts Shadow Work Journal Prompts Journal Prompts for Overcoming Fear Journal Prompts for Dealing with Loss Journal Prompts for Discerning and Decision Making Travel Journal Prompts Fun Journal Prompts

Enriching Creative Writing Activities for Kids

You may also like, planner review: roterunner’s purpose planner.

What is Deep Work? How to Do More Focused Work that Matters

How to start and keep a gardening journal: a guide to garden diaries, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Productivity

- Favorite Journals

Teachers Workshop

A Duke TIP Blog

Why Teach Creative Writing? Part 2

October 9, 2017 By Lyn Fairchild Hawks 2 Comments

This post provides a rationale for teaching creative writing more often and how to balance instructional goals and structure weekly lessons to accommodate creative writing. This is part of a larger series on integrating creative writing in your curriculum. Part 1 is here .

Back to basics.

The first question that might come to mind is WHEN? Sure, we might love getting creative with kids, but how do we make enough time for ALL THE OTHER STUFF?

By linking to standards and making use of the writing workshop structure, more creative expression is possible every week.

Our first answer is, the Common Core English Language Arts standards work beautifully hand in hand with creative writing tasks. The following seventh grade Common Core English Language Arts standards are just some that dovetail beautifully with creative writing (whether fiction or memoir, also known as creative nonfiction).

Whether it’s a blog post, or epic poem, or whether it’s a how-to manual or a screenplay, or whether a persuasive argument or a graphic novella–students can harness any one of these standards and skills below. Professional writers–novelists, journalists, marketers, screenwriters, playwrights, lyricists–spend their entire careers refining these competencies.

These standards, which also focus Duke TIP’s unit, Creative Writing: Adventures Through Time, can spiral up through higher standards in any week of your curriculum where a student must write a story that compels the reader to read on.

How do you thread creative writing across curriculum? Share with us below!

Sample writing standards that connect.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3 : Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, relevant descriptive details, and well-structured event sequences.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3a : Engage and orient the reader by establishing a context and point of view and introducing a narrator and/or characters; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally and logically.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3b : Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, and description, to develop experiences, events, and/or characters.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3c : Use a variety of transition words, phrases, and clauses to convey sequence and signal shifts from one time frame or setting to another.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3d : Use precise words and phrases, relevant descriptive details, and sensory language to capture the action and convey experiences and events.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.3e : Provide a conclusion that follows from and reflects on the narrated experiences or events.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.7.10 : Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of discipline-specific tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Ask yourself how much your students are writing regularly, both in short and long form, and how much they are putting into practice models you give them and the analysis your teaching encourages. What you’re looking for, ultimately, is more practice time. Is that mini-lesson on the apostrophe or the metaphor, or that whole-group activity acting out a scene from the novel as crucial as pursuing meaningful writing tasks? Discarding the fun and cool activity or the didactic teaching and subsequent practice can feel like a Sophie’s Choice but sometimes it’s really worth it.

Make the Links

Approach mentor texts with the lens of “How/Why did this author do that?” If students are practicing professional writers, they should lean in close to examine the method to authors’ magic. They should be stepping back to discuss these techniques and then head off to try it themselves.

Taking that angle as you craft discussion questions–knowing that the next time students see the term for a particular technique, they’ll be utilizing it themselves–is a way to shape analysis of mentor texts–from the worksheet to the small group to the discussion to the large group discussion. You can convert what were once quiz and test questions into real-time discussion questions, and get students to creative writing.

Formative writing assessments of 50-100 words, rather than short answer or multiple choice quizzes, are the best ways to test particular writing concepts and skills, as well as knowledge such as grammar and mechanics. For example:

- Original test question: Explain why Scout beat up Walter Cunningham using her backstory and character traits. –> Becomes in-class discussion question

- New formative assessment/homework or in-class assignment: Write a scene of backstory where one of your characters bullies someone else. Establish back story and character traits in this scene.

This doesn’t mean you never, ever ask another literary analysis question on a test. Those should indeed pepper our culminating assessments. But so should creative writing prompts asking students to show what they know. Having students practice both before the summative will develop deeper understandings.

Make it Happen

Writing workshops are driven by student interest and require students to regularly determine audience and purpose in their writing. Writing workshops create agency, daily. They develop independence and persistence. They create a habit of mind that’s a definite paradigm switch for many students, so it’s a process that won’t manifest results immediately.

The writing workshop structure requires extensive on-task writing time, peer review time, teacher review time, and reading time. It’s fueled by student choice.

With all that is expected of educators by local, state, and national standards, we recommend the whole-part-whole approach as you integrate workshops. Here is a typical week’s design we recommend. Take it, modify it, critique it, and tell us what you think. What do you do?

Day 1: Whole group instruction, groupwork, and skill assessment

- Teach a mini lesson via direct instruction, using mentor texts, led by standards.

- Offer different levels of direct practice exercises for small groups.

- Circulate to provide direct instruction to groups and individuals..

- Some days, alternate with 30-45 minute Socratic discussions of literary texts or whole-group activities such as debates, scene re-enactment, special projects.

- Give formative and summative assessments every few weeks (timed analytical writing–essays and short-answer questions–and grammar quizzes). Note that these should not occur until students have built a few months’ of confidence with Socratic literary discussion. For more on designing Socratic seminars on texts, visit Paideia Active Learning . Provide creative writing prompts on some of these per the model above.

- Homework: Provide further practice and writing prompts and extension activities that prepare students for summative assessments.

Days 2 and 3: Writing and reading workshops

- Allow independent and small group reading and writing, per the Atwell design .

- Expect students to produce one to two pieces a month. Allow students, like professional writers, to work on more that one piece at a time.

- Allow students who have successfully produced an individual work.

- Homework: Ongoing work on individual student pieces. A writing assignment fueled by student choice might need several nights of homework and lead to an exciting portfolio.

Day 4: Whole group instruction, groupwork, and skill assessment

Day 5: Peer review and Performance

- Feedback routines between and among students, and pair or one-to-one conferences

- Sharing for an audience, with celebrations of formative and summative accomplishments, and goal setting, with discussions of areas for growth.

For more detail on designing the day-to-day writing workshop structure, be sure to check out Nancie Atwell’s work .

About Lyn Fairchild Hawks

Lyn Fairchild Hawks currently serves as Director for Curriculum and Instruction for Duke TIP’s distance learning programs, where she supervises teachers and designs curricula and online student benefits. A long-time teacher, Lyn has published curricula with TIP, NCTE, Chicago Review Press, and ASCD. She is author of Teaching Julius Caesar: A Differentiated Approach and coauthor of Teaching Romeo and Juliet: A Differentiated Approach and The Compassionate Classroom: Lessons that Nurture Wisdom and Empathy . She is also an author of the young-adult novel, How Wendy Redbird Dancing Survived the Dark Ages of Nought , for high school students, and coauthor of the graphic novella, Minerda , for middle grade students. She is represented by Tara Gelsomino of One Track Literary Agency.

January 4, 2018 at 7:33 pm

I loved creative writing as a student and made an effort to work it in to my middle grades instruction as often as possible. I have been known to beg principals to include a Creative Writing class in the schedule as an option for students. There was no room around the “other stuff,” though, and the best I could get was a Creative Writing club…but those students sure put together an amazing literary magazine!

I agree that the workshop model is the way to ensure that students have opportunities to be creative while at the same time answering to the standards of the curriculum.

January 7, 2018 at 4:34 pm

It’s so crucial, Cindi. We’re immersed in story, we seek story, we crave stories as humans. It’s the foundation of our politics (the American story), our faiths (scared texts and our heroes within), our scientific theories and how they were discovered and enhanced…I could go on. And so it’s funny how we’ve come to a place in education where we must squeeze it in–much like other arts and exercise–as incidental to the “curriculum.” I’ve loved what students have created in these extracurriculars, too, and seen some magnificent work.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Conversation

- Karrie on Architecture: Discover, Dream, Design

- Kailey on Architecture: Discover, Dream, Design

- Earnestine on 5 Ways to Ignite Gifted Kids’ Curiosity

- From Objective to Assessment: Aligning Your Lesson Plans - TeachEDX on Making a PBL Mystery: Build Those Bones

- Zearlene Roberts on 5 Ways to Ignite Gifted Kids’ Curiosity

Find Your Content

- Teaching Setting in Fiction Writing: Creating Creative Places

When it comes to fiction writing, sometimes teaching setting can be the most daunting.

When helping students with setting, I often follow a very specific set of steps to guide them through so that they can create the most perfect setting for their story. I found these steps to not only increase student productively and engagement, but reduce all of that “I don’t know what to write” that we LOVE to hear during our writing block.

**1. Nailing Down “Time” When Teaching Setting

Introduce your students to the concept of time in storytelling. Encourage them to experiment with different eras, from the medieval times of knights and castles to the futuristic landscapes of space and technology. Help them understand how the choice of time setting can influence the tone and mood of their stories.

Tip for Teachers: Spark their creativity by asking questions like “What would happen if your characters lived in the age of dinosaurs? How would their daily lives be different?”

**2. Using the Correct Location

Guide your writers in selecting the perfect backdrop for their stories. Discuss the impact of different locations on the plot and characters. Whether it’s a bustling city, a mysterious forest, or an underwater kingdom, emphasize the importance of vivid descriptions when teaching setting to transport readers into the heart of the story.

Tip for Teachers: Encourage students to close their eyes and imagine the setting. What do they see, hear, and smell? Help them translate these sensory experiences into words.

**3. Fascinating Facts: Adding Spice to the Story

Teach kids the power of interesting facts in enriching their narratives. Whether it’s a historical event, a scientific discovery, or a cultural tradition, integrating these details not only adds depth to the setting but also makes the story more engaging. Emphasize the importance of research in creating believable worlds when teaching setting to your students!

Tip for Teachers: Challenge students to become mini-experts on a chosen topic related to their story. This not only enhances their writing but also broadens their knowledge base.

**4. Creating the Perfect Mood

Help students understand the emotional impact their settings can have on the reader. Discuss how the choice of words and descriptions can create a mood that enhances the overall experience. Whether it’s a spooky haunted house or a cheerful carnival, guide them in setting the emotional tone.

Tip for Teachers: Use visual prompts or music to evoke specific moods. Ask students to describe how these stimuli make them feel and incorporate those emotions into their writing.

**5. Sensory Symphony: Painting with Descriptive Details

Encourage the use of sensory details to bring settings to life. Remind students that readers want to experience the story through sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Challenge them to paint a vivid picture in the minds of their readers by incorporating sensory details seamlessly into their narratives.

Tip for Teachers: Engage students in hands-on sensory experiences related to their settings. If it’s a beach scene, bring in sand and seashells to stimulate their senses.

These steps have proven to be extremely beneficial in helping my students create the perfect settings for their stories.

Would you like a resource to help with this? Check out my Developing Setting resource by clicking here!

Need help developing ideas for character traits? Try this blog post!

How to Help Students Create Believable Characters

Happy Writing!

- creative writing

- Student Writing

- teaching ideas

- teaching setting

- teaching writing

- upper elementary

- writing centers

- writing strategies

- writing time

Related Articles

- Why You Need to Be Teaching Tiered Vocabulary

Vocabulary instruction is often overlooked, since it is typically embedded in our overall daily…

- How do you know which vocabulary words you should be teaching?

How do you know which vocabulary words you should be teaching? Two questions…

- Making the Most of Your Morning Work : A Vocabulary Focus

Morning Work Activities Picture this. You wake up in the morning and enter your classroom…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Posts

- Interesting Nonfiction Topics Kids Love to Learn About

Recent Comments

- LMBLiteracy on Using Color as a Writing Strategy

- Maerea on Using Color as a Writing Strategy

- Carrie Rock on Tips for Teaching in a Departmentalized Classroom

- mysite on Teaching Content Through Poetry

- LMBLiteracy on Tips for Teaching in a Departmentalized Classroom

- January 2024

- December 2021

- February 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- Teaching Ideas

- Uncategorized

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

How to Teach Creative Writing | 7 Steps to Get Students Wordsmithing

“I don’t have any ideas!”

“I can’t think of anything!”

While we see creative writing as a world of limitless imagination, our students often see an overwhelming desert of “no idea.”

But when you teach creative writing effectively, you’ll notice that every student is brimming over with ideas that just have to get out.

So what does teaching creative writing effectively look like?

We’ve outlined a seven-step method that will scaffold your students through each phase of the creative process from idea generation through to final edits.

7. Create inspiring and original prompts

Use the following formats to generate prompts that get students inspired:

- personal memories (“Write about a person who taught you an important lesson”)

- imaginative scenarios

- prompts based on a familiar mentor text (e.g. “Write an alternative ending to your favorite book”). These are especially useful for giving struggling students an easy starting point.

- lead-in sentences (“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”).

- fascinating or thought-provoking images with a directive (“Who do you think lives in this mountain cabin? Tell their story”).

Don’t have the time or stuck for ideas? Check out our list of 100 student writing prompts

6. unpack the prompts together.

Explicitly teach your students how to dig deeper into the prompt for engaging and original ideas.

Probing questions are an effective strategy for digging into a prompt. Take this one for example:

“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”

Ask “What questions need answering here?” The first thing students will want to know is:

What happened overnight?

No doubt they’ll be able to come up with plenty of zany answers to that question, but there’s another one they could ask to make things much more interesting:

Who might “I” be?

In this way, you subtly push students to go beyond the obvious and into more original and thoughtful territory. It’s even more useful with a deep prompt:

“Write a story where the main character starts to question something they’ve always believed.”

Here students could ask:

- What sorts of beliefs do people take for granted?

- What might make us question those beliefs?

- What happens when we question something we’ve always thought is true?

- How do we feel when we discover that something isn’t true?

Try splitting students into groups, having each group come up with probing questions for a prompt, and then discussing potential “answers” to these questions as a class.

The most important lesson at this point should be that good ideas take time to generate. So don’t rush this step!

5. Warm-up for writing

A quick warm-up activity will:

- allow students to see what their discussed ideas look like on paper

- help fix the “I don’t know how to start” problem

- warm up writing muscles quite literally (especially important for young learners who are still developing handwriting and fine motor skills).

Freewriting is a particularly effective warm-up. Give students 5–10 minutes to “dump” all their ideas for a prompt onto the page for without worrying about structure, spelling, or grammar.

After about five minutes you’ll notice them starting to get into the groove, and when you call time, they’ll have a better idea of what captures their interest.

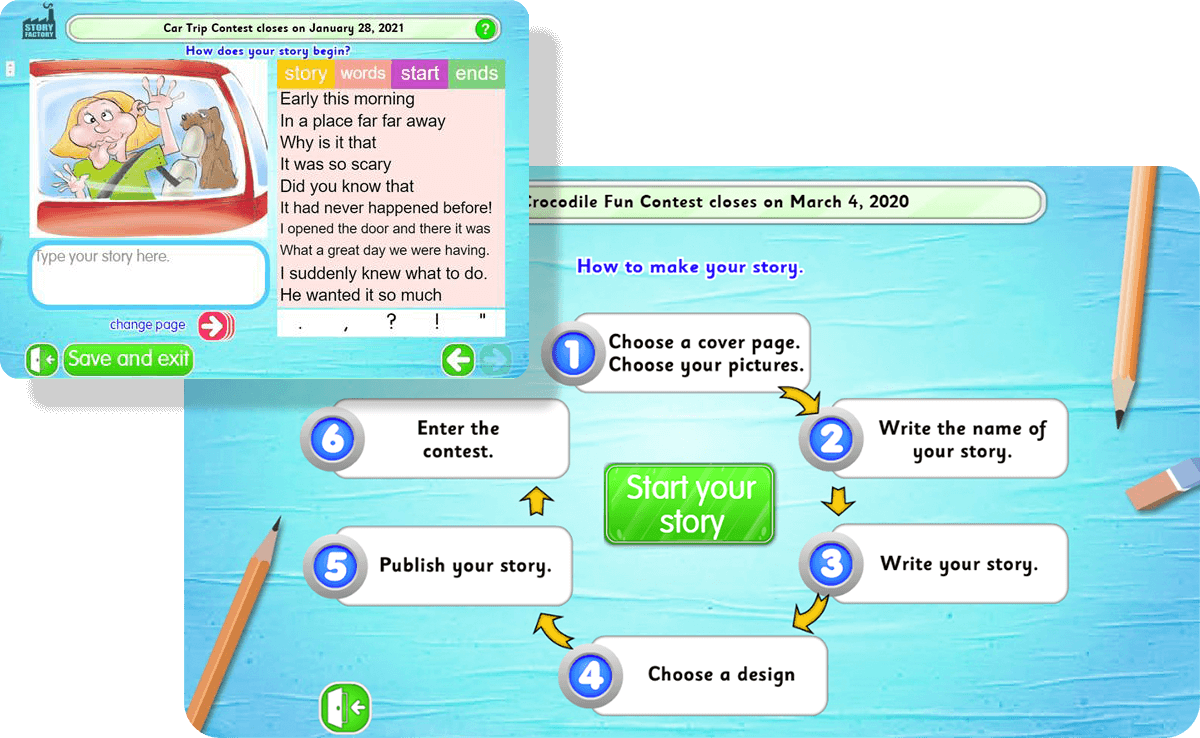

Did you know? The Story Factory in Reading Eggs allows your students to write and publish their own storybooks using an easy step-by-step guide.

4. Start planning

Now it’s time for students to piece all these raw ideas together and generate a plan. This will synthesize disjointed ideas and give them a roadmap for the writing process.

Note: at this stage your strong writers might be more than ready to get started on a creative piece. If so, let them go for it – use planning for students who are still puzzling things out.

Here are four ideas for planning:

Graphic organisers

A graphic organiser will allow your students to plan out the overall structure of their writing. They’re also particularly useful in “chunking” the writing process, so students don’t see it as one big wall of text.

Storyboards and illustrations

These will engage your artistically-minded students and give greater depth to settings and characters. Just make sure that drawing doesn’t overshadow the writing process.

Voice recordings

If you have students who are hesitant to commit words to paper, tell them to think out loud and record it on their device. Often they’ll be surprised at how well their spoken words translate to the page.

Write a blurb

This takes a bit more explicit teaching, but it gets students to concisely summarize all their main ideas (without giving away spoilers). Look at some blurbs on the back of published books before getting them to write their own. Afterward they could test it out on a friend – based on the blurb, would they borrow it from the library?

3. Produce rough drafts

Warmed up and with a plan at the ready, your students are now ready to start wordsmithing. But before they start on a draft, remind them of what a draft is supposed to be:

- a work in progress.

Remind them that if they wait for the perfect words to come, they’ll end up with blank pages .

Instead, it’s time to take some writing risks and get messy. Encourage this by:

- demonstrating the writing process to students yourself

- taking the focus off spelling and grammar (during the drafting stage)

- providing meaningful and in-depth feedback (using words, not ticks!).

Reading Eggs also gives you access to an ever-expanding collection of over 3,500 online books!

2. share drafts for peer feedback.

Don’t saddle yourself with 30 drafts for marking. Peer assessment is a better (and less exhausting) way to ensure everyone receives the feedback they need.

Why? Because for something as personal as creative writing, feedback often translates better when it’s in the familiar and friendly language that only a peer can produce. Looking at each other’s work will also give students more ideas about how they can improve their own.

Scaffold peer feedback to ensure it’s constructive. The following methods work well:

Student rubrics

A simple rubric allows students to deliver more in-depth feedback than “It was pretty good.” The criteria will depend on what you are ultimately looking for, but students could assess each other’s:

- use of language.

Whatever you opt for, just make sure the language you use in the rubric is student-friendly.

Two positives and a focus area

Have students identify two things their peer did well, and one area that they could focus on further, then turn this into written feedback. Model the process for creating specific comments so you get something more constructive than “It was pretty good.” It helps to use stems such as:

I really liked this character because…

I found this idea interesting because it made me think…

I was a bit confused by…

I wonder why you… Maybe you could… instead.

1. The editing stage

Now that students have a draft and feedback, here’s where we teachers often tell them to “go over it” or “give it some final touches.”

But our students don’t always know how to edit.

Scaffold the process with questions that encourage students to think critically about their writing, such as:

- Are there any parts that would be confusing if I wasn’t there to explain them?

- Are there any parts that seem irrelevant to the rest?

- Which parts am I most uncertain about?

- Does the whole thing flow together, or are there parts that seem out of place?

- Are there places where I could have used a better word?

- Are there any grammatical or spelling errors I notice?

Key to this process is getting students to read their creative writing from start to finish .

Important note: if your students are using a word processor, show them where the spell-check is and how to use it. Sounds obvious, but in the age of autocorrect, many students simply don’t know.

A final word on teaching creative writing

Remember that the best writers write regularly.

Incorporate them into your lessons as often as possible, and soon enough, you’ll have just as much fun marking your students’ creative writing as they do producing it.

Need more help supporting your students’ writing?

Read up on how to get reluctant writers writing , strategies for supporting struggling secondary writers , or check out our huge list of writing prompts for kids .

Watch your students get excited about writing and publishing their own storybooks in the Story Factory

You might like....

- How to write a story

- How to write a novel

- How to write poetry

- Dramatic writing

- How to write a memoir

- How to write a mystery

- Creative journaling

- Publishing advice

- Story starters

- Poetry prompts

- For teachers

How to Teach Writing - Resources for Creative Writing Teachers

Fiction writing course syllabus with lesson plans, fiction writing exercises and worksheets, resources for teaching introductory poetry writing, resources for teaching children.

How to teach writing - general thoughts

- help students to understand the elements of craft (e.g., story structure, poetic meter, etc.) so that they can recognize them in their reading and consciously experiment with them in their writing.

- open students' eyes to the options available to them when they write a story or poem (e.g., "showing" instead of "telling", using different kinds of narrators and narrative viewpoints, using different poetic forms).

- encourage students to become close observers of the world around them and to find creative material in their environments.

- teach students the value of specificity, of using all five senses to discover details that may not be obvious to the casual observer.

- help students to separate the processes of writing and editing, to avoid self-criticism while writing their rough drafts to allow ideas to flow freely (for this to work, their teachers also have to avoid criticizing rough drafts!). Teach students to treat self-editing as a separate stage in the writing process.

- get students reading in the genre they'll be writing; e.g., if they're writing poetry, encourage them to read a lot of poems.

- help students learn to trust their own perspectives and observations, to believe that they have something interesting to say.

- teach students not to wait for inspiration, that they can write even when not inspired.

- get students excited about writing!

© 2009-2024 William Victor, S.L., All Rights Reserved.

Terms - Returns & Cancellations - Affiliate Disclosure - Privacy Policy

It's Lit Teaching

High School English and TPT Seller Resources

- Creative Writing

- Teachers Pay Teachers Tips

- Shop My Teaching Resources!

- Sell on TPT

Teaching Creative Writing: Tips for Your High School Class

When I was first told that I’d be teaching creative writing, I panicked. While I had always enjoyed writing myself, I had no idea how to show others how to do it creatively. After all, all of my professional development had focused on argumentative writing and improving test scores.

Eventually, though, I came to love my creative writing class, and I think you will too. In this post, I hope to help you with shaping your own creative writing class.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links that earn me a small commission, at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products that I personally use and love, or think my readers will find useful.

The Importance of Teaching Creative Writing

Before getting into the nitty-gritty of how to teach creative writing, let’s first remind ourselves why you should teach a creative writing class.

How often do you see students freeze in your English class, wondering if what they’re writing is “right”? How often do your students beg you to look over their work to make sure that they’re doing it “right”?

We English teachers know that there’s no such thing as “right” when it comes to writing. But our students really struggle with the idea of there being no one correct answer. Creative writing is one solution to this problem.

By encouraging our students to explore, express themselves, and play with language, we show them how fun and exploratory writing can be. I know there have been many times in my life when writing clarified my own ideas and beliefs for me; creative writing provides this opportunity for our high school students.

Plus, creative writing is just downright fun! And in this modern era of standardized testing, high-stakes grading, and just increased anxiety overall, isn’t more fun just what our students and us need?

Creative writing is playful, imaginative, but also rigorous. It’s a great balance to our standard literature or composition curriculum.

Whether you’re choosing to teach creative writing or you’re being voluntold to do so, you’re probably ready to start planning. Make it as easy as possible on yourself: grab my done-for-you Creative Writing Class here !

Otherwise, preparing for an elective creative writing class isn’t much different than preparing for any other English class .

Set your goals and choose the standards you’ll cover. Plan lessons accordingly. Then, be sure to have a way to assess student progress.

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #1: Get Clear on Your Goals

First, what do you want to achieve with your creative writing class? In some school, Creative Writing is purely a fun elective. The goal is create a class that students enjoy with a side of learning.

For other schools or district cultures, however, Creative Writing might be an intensely academic course. As a child, I went to an arts middle school. Creative writing was my major and it was taken very seriously.

The amount of rigor you wish to include in your class will impact how you structure everything . So take some time to think about that . You may want to get some feedback from your administrator or other colleagues who have taught the course.

Some schools also sequence creative writing classes, so be sure you know where in the sequence your particular elective falls. I’ve also seen schools divide creative writing classes by genre: a poetry course and a short story course.

Know what your administrator expects and then think about what you as an instructor want to accomplish with your students.

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #2: List Out Your Essential Skills

Regardless of your class’s level of rigor, there are some skills that every creative writing course should cover.

First, you need to cover the writing process. Throughout the course, students should practice brainstorming, outlining, writing, and editing their drafts. In nearly every Poem Writing Activity that I use in my class, students follow the same process. They examine a model text, brainstorm ideas, outline or fill out a graphic organizer, put together a final draft, and then share with a peer for feedback.

That last step–sharing and critiquing work–is an essential skill that can’t be overstated. Students are often reluctant to share their work, but it’s through that peer feedback that they often grow the most. Find short, casual, and informal ways to build in feedback throughout the class in order to normalize it for students.

Literary terms are another, in my opinion, must-cover topic for teaching a creative writing class. You want your students to know how to talk about their writing and others’ like an actual author. How deep into vocabulary you want to go is up to you, but by the end of the course, students should sound like writers honing their craft.

Lastly, you should cover some basic writing skills, preferably skills that will help students in their academic writing, too. I like to cover broad topics like writing for tone or including dialogue. Lessons like these will be ones that students can use in other writing assignments, as well.

Of course, if you’re teaching a creative writing class to students who plan on becoming creative writing majors in college, you could focus on more narrow skills. For me, most of my students are upperclassmen looking for an “easy A”. I try my best to engage them in activities and teach them skills that are widely applicable.

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #3: Make Sure Your Materials are Age-Appropriate

Once you know what you’re teaching, you can begin to cultivate the actual lessons you’ll present. If you pick up a book on teaching creative writing or do a quick Google search, you’ll see tons of creative writing resources out there for young children . You’ll see far less for teens.

Really, the content and general ideas around creative writing don’t change much from elementary to high school. But the presentation of ideas should .

Every high school teacher knows that teens do not like to feel babied or talked down to; make sure your lessons and activities approach “old” ideas with an added level of rigor or maturity.

Take for example the haiku poem. I think most students are introduced to haikus at some point during their elementary years. We know that haiku is a pretty simple poem structure.

However, in my Haiku Poem Writing Lesson , I add an extra layer of rigor. First, students analyze a poem in which each stanza is its own haiku. Students are asked not only to count syllables but to notice how the author uses punctuation to clarify ideas. They also analyze mood throughout the work.

By incorporating a mentor text and having students examine an author’s choices, the simple lesson of writing a haiku becomes more relevant and rigorous.

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #4: Tell Students What They Should Not Write About

You’ll often be surprised by just how vulnerable your students are willing to be with you in their writing. But there are some experiences that we teachers don’t need to know about, or are required to act on.

The first day of a creative writing course should always include a lecture on what it means to be a mandated reporter. Remind students that if they write about suicidal thoughts, abuse at home, or anything else that might suggest they’re in danger that you are required by law to report it.

Depending on how strict your district, school, or your own teaching preferences, you may also want to cover your own stance on swearing, violence, or sexual encounters in student writing. One idea is to implement a “PG-13” only rule in your classroom.

Whatever your boundaries are for student work, make it clear on the first day and repeat it regularly.

Engage your students in more creative writing!

Sign up and get five FREE Creative Writing journal prompts to use with your students!

Opt in to receive news and updates.

Keep an eye on your inbox for your FREE journal prompts!

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #5: Give Students Lots of Choice

Creative writing should be creative . Yes, you want to give students parameters for their assignments and clear expectations. But you want them to feel a sense of freedom, also.

I took a class once where the story starters we were given went on for several pages . By the time we students were able to start writing, characters had already been developed. The plot lines had already been well-established. We felt written into a corner, and we all struggled with wrapping up the loose ends that had already been created.

I’ve done an Author Study Project with my class in which students were able to choose a poet or short story author to study and emulate. My kids loved looking through the work of Edgar Allan Poe, Elizabeth Acevedo, Neil Gaiman, and Jason Reynolds for inspiration. They each gravitated towards a writer that resonated with them before getting to work.

Another example is my Fairy Tale Retelling Project. In this classic assignment, students must rewrite a fairy tale from the perspective of the villain. Students immediately choose their favorite tales, giving them flexibility and choice.

I recommend determining the form and the skills that must be demonstrated for the students . Then, let students choose the topic for their assignment.

Teaching Creative Writing Tip #6: Use Hands-On Activities

If you’re teaching a class full of students who are excited to write constantly, you can probably get away writing all class period. Many of us, however, are teaching a very different class. Your students may have just chosen an elective randomly. They might not even have known what creative writing was!

(True story–one of my creative writing students thought the class would be about making graffiti. I guess that is writing creatively!)