Hot Topics: Health Equity and Health Disparity

- Extending Your Research

Suggested Videos

Other Sites of Interest

- Health Equity: Why It Matters, and How To Take Action - RWJF Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

- Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health Insights into issues that include: Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health (NCCAH) Canada

- Office of Health Equity Part of the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration

- State Health Disparities Legislation and Minority Health Issues Statistics & reports on racial & ethnic health disparities from the National Conference of State Legislatures

What's the Issue?

The goal of health equity is everybody having the same opportunity to improve their health.

A health disparity is a preventable difference between different groups of people in

Populations affected by health disparities contend with social, economic, and environmental disadvantages. For some groups of people, health disparities are also a legacy of discrimination, exclusion, and/or policy.

Image credits: Resized " scales " by Kristen Gee , available from Noun Project , licensed under CC BY . Resized & colored "Health Services" symbol by SEGD available from Healthcare Symbols "for use in your projects." Graphics modified by Nancy R. Curtis.

Some Places to Begin

- Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity Kaiser Family Foundation issue brief, 2015

- Health Disparities: MedlinePlus

- Health Equity Boston Public Health Commission

- The Lalonde Report Officially, "A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians." Seminal document (1974) in health promotion. Proposed lifestyle & environment as factors affecting health.

- Let's Talk: Health Equity National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2013 [Canada]

- Social Determinants of Health Canadian Medical Association

- Maine Public Health Data Reports - Health Disparities

Maine Health Access Foundation (MeHAF) data briefs & analyses include a statewide view of rural health, rural health profiles of each county, and more:

- Low-Income, Uninsured Mainers Face Substantial Challenges Getting Health Care

- Mental Health Status and Access to Health Care Services for Adults in Maine

Kaiser Family Foundation materials include:

- Disparities in Health and Health Care: Five Key Questions and Answers

- Eliminating Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health Care: What are the Options?

- Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Individuals in the U.S.

- Health and Health Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs)

- Health and Health Care for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders (NHOPIs) in the United States

- Health and Health Care for Blacks in the United States

- Health and Health Care for Hispanics in the United States

- Health Coverage of Immigrants

- Living in an Immigrant Family in America: How Fear and Toxic Stress are Affecting Daily Life, Well-Being, & Health

Other resources:

- The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014 The Health Inequality Project, 2016

- Health Disparities and People with Disabilities American Association on Health and Disability, 2011

- A New Way to Talk About the Social Determinants of Health Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010. Bridging the gap between academe & communities while minimizing political perspectives and agendas.

- Rural Health Disparities Rural Health Information Hub

- Colour Coded Health Care: The Impact of Race and Racism on Canadians’ Health

- Ensuring Equitable Access to Care: Strategies for Governments, Health System Planners, and the Medical Profession Canadian Medical Association Position Statement [2013?]

- Health Care in Canada: What Makes us Sick? Canadian Medical Association Town Hall Report, July 2013. Summarizes public discussions on social determinants of health. Lists recommendations for further action.

- Thirteen Public Interventions in Canada That Have Contributed to a Reduction in Health Inequalities National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, 2010

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic [RWJF]

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on RWJF.org

- Next: Extending Your Research >>

- Last Updated: Dec 22, 2023 12:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.umaine.edu/health-equity-disparity

5729 Fogler Library · University of Maine · Orono, ME 04469-5729 | (207) 581-1673

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Ending structural racism, minority health and health disparities research, nih is committed to:.

1. Improving minority health and reducing health disparities.

2. Removing the barriers to advancing health disparities research.

Health disparities are preventable differences in health status and outcomes that adversely affect certain populations. Research on health disparities examines the influence of environment, social determinants, and other underlying mechanisms leading to differences in health outcomes. This multidisciplinary field of science also seeks to identify evidence-based approaches to reduce the unequal burdens of morbidity and mortality among disparity populations defined as racial/ethnic minority, low socio-economic status, rural, and sexual and gender minority populations in the United States.

At NIH, every Institute and Center (IC) supports research into the causes of and potential interventions for health disparities within their mission. However, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) is the lead institute on research to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. NIH recognizes the need to increase the proportion of research on minority health and health disparities across the NIH ICs to address public health issues affecting all populations in the United States. Learn more about NIMHD’s efforts .

“Of the many factors that contribute to health disparities, structural racism lies at the center of many by perpetuating established social and health injustices.”

— Eliseo Pérez-Stable, M.D., Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities

To address long-standing health disparities and promote health equity, efforts under UNITE will seek to improve transparency, accountability, and sustainability in support for research on minority health and health disparities.

Concrete actions to achieve this goal include:

- Support late-stage translation of multi-level, multi-factor interventions to reduce health disparities.

- Test innovative approaches to address structural racism and eliminate health disparities.

- Marshal adequate and measurable resources across NIH for scientific research that will produce significant reductions in health disparities and improve minority health.

- Develop infrastructure to coordinate/track NIH-wide minority health and health disparities research

- Examine minority health and health disparities research portfolios with NIH-wide stakeholders to aggregate and generate summary recommendations for addressing research and funding gaps.

- Review the scope of NIH intramural and extramural systems, methods, measures, and definitions used to track minority health and health disparity research to identify strengths and limitations of current systems and new models.

- Conduct an analysis of current investments in minority health and health disparity research by intramural and extramural stakeholders.

- Ensure a robust NIH enterprise-wide commitment to support the NIH Strategic Plan on Minority Health and Health Disparities focused on the effects of structural racism and discrimination on minority health and health disparities.

- Support research on behavioral, biological, and social determinants of health and structural racism and discrimination.

This page last reviewed on August 25, 2022

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Mission and Vision

- Scientific Advancement Plan

- Science Visioning

- Research Framework

- Minority Health and Health Disparities Definitions

- Organizational Structure

- Staff Directory

- About the Director

- Director’s Messages

- News Mentions

- Presentations

- Selected Publications

- Director's Laboratory

- Congressional Justification

- Congressional Testimony

- Legislative History

- NIH Minority Health and Health Disparities Strategic Plan 2021-2025

- Minority Health and Health Disparities: Definitions and Parameters

- NIH and HHS Commitment

- Foundation for Planning

- Structure of This Plan

- Strategic Plan Categories

- Summary of Categories and Goals

- Scientific Goals, Research Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Research-Sustaining Activities: Goals, Strategies, and Priority Areas

- Outreach, Collaboration, and Dissemination: Goals and Strategies

- Leap Forward Research Challenge

- Future Plans

- Research Interest Areas

- Research Centers

- Research Endowment

- Community Based Participatory Research Program (CBPR)

- SBIR/STTR: Small Business Innovation/Tech Transfer

- Solicited and Investigator-Initiated Research Project Grants

- Scientific Conferences

- Training and Career Development

- Loan Repayment Program (LRP)

- Data Management and Sharing

- Social and Behavioral Sciences

- Population and Community Health Sciences

- Epidemiology and Genetics

- Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP)

- Coleman Research Innovation Award

- Health Disparities Interest Group

- Art Challenge

- Breathe Better Network

- Healthy Hearts Network

- DEBUT Challenge

- Healthy Mind Initiative

- Mental Health Essay Contest

- Science Day for Students at NIH

- Fuel Up to Play 60 en Español

- Brother, You're on My Mind

- Celebrating National Minority Health Month

- Reaching People in Multiple Languages

- Funding Strategy

- Active Funding Opportunities

- Expired Funding Opportunities

- Technical Assistance Webinars

- Community Health and Population Sciences

- Clinical and Health Services Research

- Integrative Biological and Behavioral Sciences

- Intramural Research Program

- Training and Diverse Workforce Development

- Inside NIMHD

- ScHARe HDPulse PhenX SDOH Toolkit Understanding Health Disparities For Research Applicants For Research Grantees Research and Training Programs Reports and Data Resources Health Information for the Public Science Education

- Publications

The Science of Health Disparities Research

- Director's Corner

- Legislative Information

- Strategic Plan

- NIMHD Celebrates Its 10 Year Anniversary

- Advisory Council

- Employment Opportunities

Over the years, research in minority health and health disparities has evolved from a descriptive understanding of what health disparities are and who is most affected, to the discovery of the complexity of factors involved in determining health and its outcomes by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Scientific approaches to addressing these factors lead to:

- Improved understanding of mechanisms.

- More options to implement interventions to reduce disparities.

- Greater access to health care.

- A more equitable future.

The Science of Health Disparities Research is an in-depth volume for comprehensive information on conducting clinical and translational health disparities studies.

NIMHD researchers—along with leading experts from around the country—have written this 26-chapter textbook to cover the spectrum of health disparities research. This important new resource:

- Defines the field of health disparities science.

- Explains basic definitions, principles, and concepts for identifying, understanding, and addressing health disparities.

- Suggests new directions in scholarship and research.

- Discusses population health training, capacity building, and the transdisciplinary tools needed to advance health equity.

With contributions from more than 100 recognized scholars and leaders in the field, The Science of Health Disparities Research describes how using an interdisciplinary approach can reduce inequalities in population health studies, the importance of adding community engagement to the research process, and the ways that rigorous research can promote social justice. It also features examples from contemporary research studies, highlights conceptual models, and includes a broad range of scientific perspectives. The lifelong work of the scientists, clinicians, and community-based researchers and their contributions to the scientific literature on minority health and health disparities research provide a strong foundation for this text.

“The chapters contained herein illustrate the importance and feasibility of systematic, rigorous inquiry for understanding the specifics of minority health and health disparities. They also convey the importance of the lessons learned for science in general: for discovery, for generalizability, for advancing theory, for enhancing measurement, for improving investigative methods, for promoting attention to neglected areas of research, and for diversifying the scientific work workforce.”

-Spero M. Manson, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of Public Health and Psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Public Health

Intended Audience

This textbook is useful to a variety of audiences. Besides being an essential resource for trainees and clinical researchers in health services, behavioral science, population science, public health and basic science as it intersects with clinical studies, The Science of Health Disparities Research appeals to health care policy makers, epidemiologists, intervention scientists, and clinicians, particularly those working with minority, vulnerable, or underserved populations, health disparity scientists, community-based researchers, and research institutes.

Chapter Topics

- Definitions, Principles, and Concepts for Minority Health and Health Disparities Research

- Racial/Ethnic, Socioeconomic, and Other Social Determinants

- Applying Self‐report Measures in Minority Health and Health Disparities Research

- Applications of Big Data Science and Analytic Techniques for Health Disparities Research

- Healthcare and Public Policy: Challenges and Opportunities for Research

- Addressing Disparities in Access to High-quality Care

- Role of Electronic Health Records and Health Information Technology in Addressing Health Disparities

- Recruitment, Inclusion, and Diversity in Clinical Trials

- Workforce Diversity and Capacity Building to Address Health Disparities

For questions about the textbook, please email [email protected] .

Page updated Oct. 16, 2023

Staying Connected

- Funding Opportunities

- News & Events

- HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

- Privacy/Disclaimer/Accessibility Policy

- Viewers & Players

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Special 07 April 2021

Highlighting Research on Health Disparities

A collection aimed at highlighting NPP articles and commentaries that address disparities related to gender, race, ethnicity, LGBTQ+ individuals, and early life adversity

Academic ethics of mental health: the national black postdocs framework for the addressment of support for undergraduate and graduate trainees

- Cellas A. Hayes

- Almarely L. Berrios-Negron

- Frankie D. Heyward

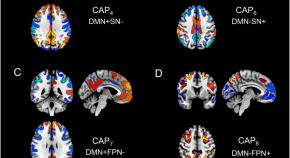

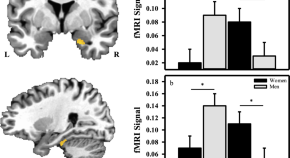

Sex-specific resting state brain network dynamics in patients with major depressive disorder

- Daifeng Dong

- Diego A. Pizzagalli

- Emily L. Belleau

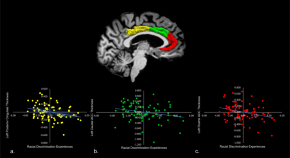

The effects of experience of discrimination and acculturation during pregnancy on the developing offspring brain

- Marisa N. Spann

- Kiarra Alleyne

- Dustin Scheinost

Digital and precision clinical trials: innovations for testing mental health medications, devices, and psychosocial treatments

- John Torous

- Patricia Arean

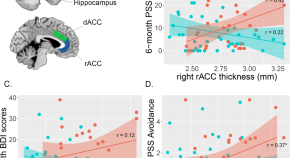

Associations between childhood ethnoracial minority density, cortical thickness, and social engagement among minority youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis

- Benson S. Ku

- Meghan Collins

- Elaine F. Walker

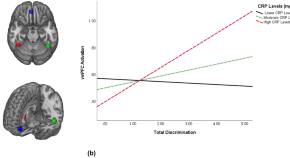

C-reactive protein moderates associations between racial discrimination and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activation during attention to threat in Black American women

- Aziz Elbasheir

- Jennifer C. Felger

Brain health in ethnically minority youth at risk for psychosis

- Rachel A. Rabin

- Lena Palaniyappan

Ensuring psychedelic treatments and research do not leave anyone behind

Psychedelics are a promising approach to caring for persons living with severe mental illness. However, as with all clinical treatments and research in the US, health equity concerns must be considered and addressed. Ensuring health equity and health justice in psychedelic care delivery and research will require strategies to not only reduce disparities and preempt future disparities among minoritized and marginalized populations.

- Melissa A. Simon

The biological embedding of structural inequities: new insight from neuroscience

- E. Kate Webb

- Nathaniel G. Harnett

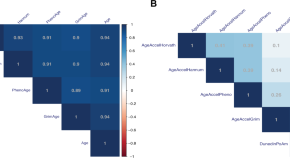

Transdiagnostic evaluation of epigenetic age acceleration and burden of psychiatric disorders

- Natan Yusupov

- Linda Dieckmann

- Elisabeth B. Binder

Ethical considerations in rapid and novel treatments in psychiatry

- Tobias Haeusermann

- Winston Chiong

Perspective on equitable translational studies and clinical support for an unbiased inclusion of the LGBTQIA2S+community

- Teddy G. Goetz

- Krisha Aghi

- Troy A. Roepke

To dismantle structural racism in science, scientists need to learn how it works

- Caleb Weinreb

- Daphne S. Sun

Five recommendations for using large-scale publicly available data to advance health among American Indian peoples: the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study SM as an illustrative case

- Evan J. White

- Mara J. Demuth

- Robin Aupperle

Deconstructing dissociation: a triple network model of trauma-related dissociation and its subtypes

- Lauren A. M. Lebois

- Poornima Kumar

- Milissa L. Kaufman

Building an intentional and impactful summer research experience to increase diversity in mental health research

- Oluwarotimi O. Folorunso

- Karen Burns White

- Elena H. Chartoff

Sex-dependent risk factors for PTSD: a prospective structural MRI study

- Alyssa R. Roeckner

- Shivangi Sogani

- Jennifer S. Stevens

Sex-related differences in violence exposure, neural reactivity to threat, and mental health

- Heather E. Dark

- David C. Knight

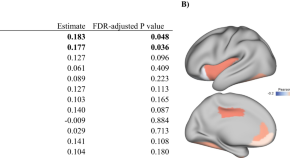

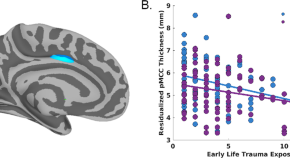

Racial discrimination associates with lower cingulate cortex thickness in trauma-exposed black women

- Leyla Eghbalzad

- Bekh Bradley

The role of racial discrimination in dissociation and interoceptive dysfunction

- Sahib S. Khalsa

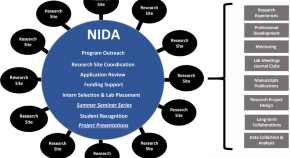

The National Institute on Drug Abuse Summer Research Internship Program: Building a Diverse National Scientific Workforce

- Albert H. Avila

- Jason H. Weixelbaum

- Wilson M. Compton

It’s about racism, not race: a call to purge oppressive practices from neuropsychiatry and scientific discovery

- Sierra E. Carter

- Yara Mekawi

Cross-ancestry genomic research: time to close the gap

- Elizabeth G. Atkinson

- Sevim B. Bianchi

- Sandra Sanchez-Roige

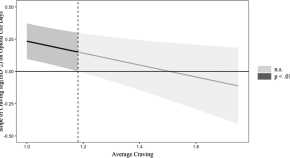

Intra-individual variability and stability of affect and craving among individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder

- Jennifer D. Ellis

- Chung Jung Mun

- Kenzie L. Preston

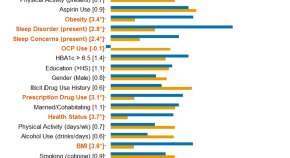

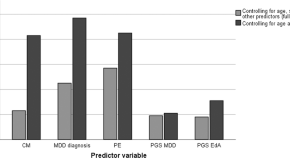

Does the moderator matter? Identification of multiple moderators of the association between peripheral inflammatory markers and depression severity in a large racially diverse community cohort

- Manivel Rengasamy

- Sophia Arruda Da Costa E Silva

- Rebecca B. Price

Altered reward and effort processing in children with maltreatment experience: a potential indicator of mental health vulnerability

- Diana J. N. Armbruster-Genç

- Vincent Valton

- Eamon McCrory

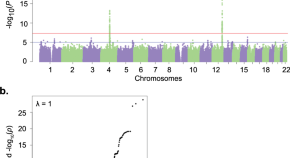

Genome-wide meta-analysis of alcohol use disorder in East Asians

- Rasmon Kalayasiri

- Joel Gelernter

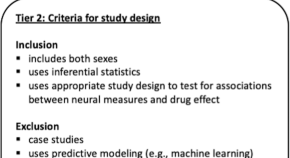

Evaluating the evidence for sex differences: a scoping review of human neuroimaging in psychopharmacology research

- Korrina A. Duffy

- C. Neill Epperson

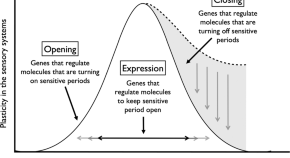

Sensitive period-regulating genetic pathways and exposure to adversity shape risk for depression

- Min-Jung Wang

- Erin C. Dunn

A three-factor model of common early onset psychiatric disorders: temperament, adversity, and dopamine

- Maisha Iqbal

- Sylvia Maria Leonarda Cox

- Marco Leyton

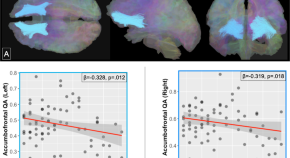

Accumbofrontal tract integrity is related to early life adversity and feedback learning

- Bryan V. Kennedy

- Jamie L. Hanson

- Seth D. Pollak

Brain sex differences: the androgynous brain is advantageous for mental health and well-being

- Barbara J. Sahakian

Transcriptome-wide association study of post-trauma symptom trajectories identified GRIN3B as a potential biomarker for PTSD development

- Adriana Lori

- Katharina Schultebraucks

- Kerry J. Ressler

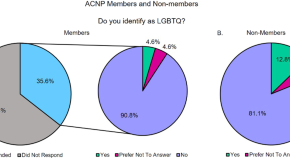

Being counted: LGBTQ+ representation within the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP)

- Hayley Fisher

NIH research funding disparities affect diversity, equity and inclusion goals of the ACNP

- Michael A. Taffe

Distinct cortical thickness correlates of early life trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder are shared among adolescent and adult females with interpersonal violence exposure

- Marisa C. Ross

- Anneliis S. Sartin-Tarm

- Josh M. Cisler

Inaction speaks louder than words: tips for increasing black ACNP membership

- Carl L. Hart

- Jean Lud Cadet

Intergenerational trauma is associated with expression alterations in glucocorticoid- and immune-related genes

- Nikolaos P. Daskalakis

- Changxin Xu

- Rachel Yehuda

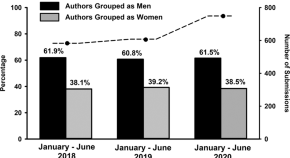

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender representation among corresponding authors of Neuropsychopharmacology (NPP) manuscripts: submissions during January–June, 2020

- Chloe J. Jordan

- William A. Carlezon Jr.

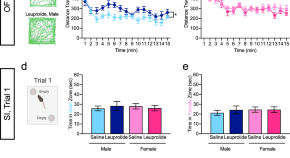

Behavioral and neurobiological effects of GnRH agonist treatment in mice—potential implications for puberty suppression in transgender individuals

- Christoph Anacker

- Ezra Sydnor

- Christine A. Denny

Childhood maltreatment and cognitive functioning: the role of depression, parental education, and polygenic predisposition

- Janik Goltermann

- Ronny Redlich

- Udo Dannlowski

Advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion in the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP): advances, challenges, and opportunities to accelerate progress

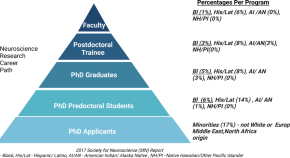

It is increasingly accepted that higher levels of excellence and innovation in research can be achieved by organizations that promote equity, diversity, and inclusion across several domains including ethnicity and gender. The purpose of this commentary is to provide an overview of the methods used to increase diversity within ACNP, as well as recommendations for accelerating progress. Annual membership surveys confirm increases in female membership and leadership positions, slower but encouraging signals for “Asian” and “Hispanic” members, and less progress for African American and other ethnic populations. Meetings have become visibly more diverse, due in part to ethnic minority travel awards and apparently increasing diversity among guest attendees. Evidence of increasing inclusion includes well-attended networking events and minority-relevant programming, active communications about diversity-related events and resources, and strong statements by ACNP leadership that embrace diversity as a core value and support collaboration among key committees and task forces to identify and implement pro-inclusion and diversity-enhancing efforts. We believe ACNP can accelerate progress with more scientifically valid approaches to assessing diversity and inclusion. The current membership survey includes five outmoded ethnic options and postmeeting surveys that are not designed to assess inclusion efforts and consequences. Measures should be developed that better characterize diversity and assess efforts to reduce the barriers that exist for potential non-White populations (e.g., annual membership and meeting attendance costs). Increased collaboration with NIH and other organizations that are committed to these same goals may also contribute to acceleration of progress by ACNP and other scientific organizations.

- Jack E. Henningfield

- Sherecce Fields

- Carlos A. Zarate

Impact of ADCYAP1R1 genotype on longitudinal fear conditioning in children: interaction with trauma and sex

- Tanja Jovanovic

- Anaïs F. Stenson

NPP statement on racism, discrimination, and abuse of power

- on Behalf of the NPP Team

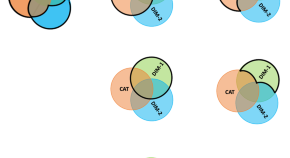

The ABCD study: understanding the development of risk for mental and physical health outcomes

- Nicole R. Karcher

- Deanna M. Barch

Evaluating the impact of trauma and PTSD on epigenetic prediction of lifespan and neural integrity

- Seyma Katrinli

- Jennifer Stevens

- Alicia K. Smith

Neurobiological consequences of racial disparities and environmental risks: a critical gap in understanding psychiatric disorders

Associations between different dimensions of prenatal distress, neonatal hippocampal connectivity, and infant memory

- Catherine Monk

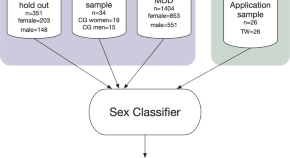

Biological sex classification with structural MRI data shows increased misclassification in transgender women

- Claas Flint

- Katharina Förster

- Dominik Grotegerd

Polygenic scores for psychiatric disorders in a diverse postmortem brain tissue cohort

- Laramie Duncan

- Hanyang Shen

- Stefano Marenco

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Womens Health (Larchmt)

Health Equity Among Black Women in the United States

Juanita j. chinn.

1 Population Dynamics Branch, Division of Extramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Iman K. Martin

2 Blood Epidemiology and Clinical Therapeutics Branch, Division of Blood Diseases and Resources, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Nicole Redmond

3 Clinical Applications and Prevention Branch, Division of Cardiovascular Sciences, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Black women in the United States have experienced substantial improvements in health during the last century, yet health disparities persist. These health disparities are in large part a reflection of the inequalities experienced by Black women on a host of social and economic measures. In this paper, we examine the structural contributors to social and economic conditions that create the landscape for persistent health inequities among Black women. Demographic measures related to the health status and health (in)equity of Black women are reviewed. Current rates of specific physical and mental health outcomes are examined in more depth, including maternal mortality and chronic conditions associated with maternal morbidity. We conclude by highlighting the necessity of social and economic equity among Black women for health equity to be achieved.

Black women in the United States experienced substantial improvements in health during the last century, yet health disparities persist. Black women continue to experience excess mortality relative to other U.S. women, including—despite overall improvements among Black women—shorter life expectancies 1 and higher rates of maternal mortality. 2 Moreover, Black women are disproportionately burdened by chronic conditions, such as anemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and obesity. Health outcomes do not occur independent of the social conditions in which they exist. The higher burden of these chronic conditions reflects the structural inequities within and outside the health system that Black women experience throughout the life course and contributes to the current crisis of maternal morbidity and mortality. The health inequities experienced by Black women are not merely a cross section of time or the result of a singular incident.

Historical Context for the Current Health Experience of Black Women

Race and ethnicity are sociocultural constructs that reflect common geographic origins, cultures, and social histories of groups that are defined by societies in time-dependent contexts. 3–6 Given the social construction of race and ethnicity, racial groups and identity are fluid; they can, and do, change over time and vary across place. 7

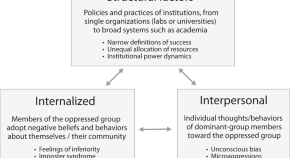

No discussion of health equity among Black women is complete unless it considers the impacts of institutional- and individual-level forms of racism and discrimination against Black people. Nor is a review of health equity among Black women complete without an understanding of the intersectionality of gender and race and the historical contexts that have accumulated to influence Black women's health in the United States.

Research consistently has documented the continued impacts of systematic oppression, bias, and unequal treatment of Black women, 5 , 8 , 9 Substantial evidence exists that racial differences in socioeconomic ( e.g. , education and employment) and housing outcomes among women are the result of segregation, discrimination, and historical laws purposed to oppress Blacks and women in the United States.

Black women earn on average $5,500 less per year and experience higher unemployment and poverty rates than the U.S. average for women ( Table 1 ). 10 Moreover, Black women are more likely to be the head of household than their White counterparts, effectively supporting more dependents with fewer resources. 10 Black women live in neighborhoods that are more racially segregated and have lower property values than their White counterparts. 10 , 11 Mortgage lending discrimination (“redlining”), a legal practice in which lenders deny mortgage loans to communities and individuals based on race, resulted in community disinvestment residential segregation. 11 Residential segregation, as Williams and Collins argued, 12 is a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health, operating through many social institutions (including labor markets and education) to affect health.

Descriptive Demographic Statistics for Black Women in the United States, 2018

Data are collected by sex (female).

Data source: https://blackdemographics.com/population/black-women-statistics 10

The intersectionality of gender and race and its impact on the health of Black women also is important. This intersection of race and gender for Black women is more than the sum of being Black or being a woman: It is the synergy of the two. Black women are subjected to high levels of racism, sexism, and discrimination at levels not experienced by Black men or White women. 13–15

In contrast to Black women, White women in the United States have benefited from living in a politically, culturally, and socioeconomically White-dominated society. 1 These benefits accumulate across generations, creating a cycle of overt and covert privileges 16 , 17 not afforded to Black women, such as wage gap differentials 18 and the invisibility of whiteness ( i.e. , not having to think about one's race). 19 , 20 These privileges do not mean that all White women are similarly advantaged nor are all Black women similarly disadvantaged.

These social conditions create the environment for health disparities to exist and persist. They are the social determinants of health, the “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” 21 Disparities in Black women's health are particular types of health differences “that are closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage.” 21

The history of Black women's access to health care and treatment by the U.S. medical establishment, particularly in gynecology, contributes to the present-day health disadvantages of Black women. Health inequality among Black women is rooted in slavery. White slave holders viewed enslaved Black women as a means of economic gain, resulting in the abuse of Black women's bodies and a disregard for their reproductive health. Black women were forced to procreate, with little or no self-agency and limited access to medical care. 22 The development of gynecology as a medical specialty in the 1850s 23 ushered in a particularly dark period for the health of Black women. With no regulations for the protection of human subjects in research, Black women were subjected to unethical experimentation without consent. 22–24 Even in more contemporary times, these abuses continue. 25 , 26

As a result of this history and the accumulation of disadvantages across generations, Black women are at the center of a public health emergency. Maternal mortality rates for non-Hispanic Black women are three to four times the maternal mortality rates of non-Hispanic White women. 2 In the next section of this article, we highlight some of the physical and mental health disparities that contribute to the current maternal mortality rates. Although discussed separately, physical health and mental health are inextricably linked.

Physical Health

Demographic characteristics.

Black women are diverse in both nativity and ethnicity. 27 They are not a monolithic group; instead, they comprise multiple cultures and languages. For the purposes of this article, “Black women” refers to the collective identities of Black women, including women of different ethnicities. In the data cited here, “Black women” refers to the women included in the original study population.

Black women currently make up ∼7.0% of the U.S. population and 13.6% of all U.S. women. 10 Although, on average, Black women are younger (36.1 years) than U.S. women overall (39.6 years) ( Table 1 ), 10 they have a higher prevalence of many health conditions, including heart disease, stroke, cancers, diabetes, maternal morbidities, obesity, and stress. Life expectancy at birth is 3 years longer for non-Hispanic White females than for non-Hispanic Black females. Infant mortality rates for children born to non-Hispanic Black women are twice as high as those for children born to non-Hispanic White women 1 ( Table 2 ).

Descriptive Health Statistics for Women

Maternal mortality and pregnancy-related mortality are per 100,000 live births.

Infant mortality rates are per 1,000 live births.

Data sources:

As adults age, their health declines. Aging is affected not only by chronological age but also by biological, behavioral, sociocultural, and environmental factors. 31 Stress, an important factor in aging, is affected strongly by exposure to the built and social environments. Geronimus et al. posit the weathering hypothesis , that is differential exposures to stressful environments are a major factor in widening health disparities as individuals age. They suggest that Black–White disparities in health widen with age because of the accumulation of socioeconomic disadvantages and experiences with racism among Black women throughout the life course. 31–35 Evidence for the weathering hypothesis includes the finding that babies born to Black women in their teens are at lower risk of infant mortality than babies born to older non-Hispanic Black women, the reverse of what is observed for non-Hispanic White women. 31 More recently, Geronimus et al. found that among women aged 49–55 years, telomere length (a biomarker of aging) indicates that Black women are 7.5 years biologically “older” than White women. Perceived stress and poverty account for 27% of this difference. 33

The relatively high levels of morbidity and mortality among Black populations in the United States are, in large part, caused by obesity, which increases the risk of stroke and various CVDs. 36–38 Obesity is a major source of morbidity and mortality for all U.S. populations, but non-Hispanic Blacks have a higher age-adjusted prevalence of obesity than any other racial/ethnic group, with estimates ranging from 34% to 50%. 39 Patterns of obesity vary by many factors across and within races, including location, gender, and educational attainment. 40 Unlike other demographic groups, higher levels of income are not protective against obesity among non-Hispanic Black women. 39 This difference in the prevalence of obesity as reflected in national adiposity data on Black women is the result of the complex multilevel interplay of the measurable and difficult-to-measure social determinants that affect health disparities. Furthermore, Black women lose less weight than other subpopulations do in behavioral weight loss intervention research, 41 and they have a positive body self-image at higher weight levels, which may be psychologically healthy, but also diminishes their motivation to lose weight. 42 These findings support the need for interventions that integrate biological, sociocultural, and environmental factors that influence obesity. 41 The high prevalence of obesity among Black women 36 , 37 impacts the prevalence rates of stroke and various CVDs. 38

Cardiovascular disease

After 50 years of declines in CVD mortality, declines stalled in 2011, with CVD mortality increasing starting in 2015. 43–45 Despite changes in the overall CVD mortality rates, racial and sex disparities persist. Compared with White women, Black women have higher rates of CVD mortality, which have been attributed to poorer cardiovascular (CV) health and a higher burden of modifiable risk factors and clinical comorbidities. 46 , 47 Furthermore, the accumulation of both clinical and behavioral CV risk factors and the manifestation of CVD at younger ages for Black women compared with other racial and ethnic groups—that is, during young adulthood and middle adulthood—have significant implications for maternal and infant health. 48 Understanding the drivers of disparities in CVD among Black women requires examining the intersection of sex as a biological variable 49 and multi-omic influences ( e.g. , genetic ancestry 50 and epigenetic characterization) with multilevel 51 ( e.g. , biological ancestry characterization, individual, interpersonal, community, and society) social constructs ( e.g. , race, ethnicity, and gender).

Although differences in CVD incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality by sex and race/ethnicity are well documented, research on the contributions of genetic factors is limited. People of African ancestry have been underrepresented in genomic research. 52 Furthermore, in genomic studies, analyses of sex chromosomes and the interaction between sex hormones and genetic characteristics are rarely included. 53 Therefore, significant concerns exist about the potential for precision medicine efforts, such as polygenic risk scores, to exacerbate CVD health disparities when using precision medicine research that relies on genetic studies that had inadequate participation from populations with African ancestry. 54

Optimizing such behavioral factors as diet, physical activity, sleep, smoking, alcohol use, emotional health, and stress management is important to maintaining CV health (primordial prevention) and reducing CVD risk (primary and secondary prevention). 55–59 Compared with non-Hispanic White women, non-Hispanic Black women aged 20 years and older have a higher prevalence of several clinical risk factors for CVD, including obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes. 60

Sleep disparities may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in CVD. 61 , 62 Blacks have a higher likelihood of short or prolonged sleep durations, obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, and other measures of poor sleep quality. A study of women of childbearing age showed that, despite Black women having poorer self-reported sleep quality, they were less likely than other women to report their sleep disturbances to a physician. 63 Sleep disturbances may be a manifestation of altered stress reactivity resulting in activation of the chronic stress response and resultant elevations in cardiometabolic disease. 64

Bleeding and blood disorders

Diseases of the blood are as numerous and complex as the fields of hematological physiology and pathophysiology. Benign blood disease include anemia (iron deficiencies), sickle cell anemia (SCD), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase disorders, and hemophilia, among others. Malignant blood diseases (cancers of the blood) include acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloproliferative neoplasms, and myelodysplastic syndrome. Well-documented differences exist in the prevalence, treatment experiences, and outcomes across races and ethnicities for most benign blood diseases, 65 , 66 and interest in observed disparities in malignancies of the blood is emerging. 67 , 68 Black women are disproportionately impacted by SCD and its complications, as well as by anemia (almost all forms), and they have poor outcomes associated with ancestrally linked disorders, such as G6PD. 69 , 70

Maternal morbidity and mortality

It is estimated that non-Hispanic Black women are three to almost four times more likely to die while pregnant or within 1 year postpartum than their non-Hispanic White and Latina counterparts. 2 The racial disparity in mortality persists at every education level 2 and has persisted or increased over time. 71 As detailed in the sections above, Black women have elevated prevalence rates of chronic conditions associated with higher risk of severe maternal morbidity and mortality. 72 Some of the leading causes of maternal morbidities resulting in pregnancy-associated death occur more in non-Hispanic Black women ( e.g. , hemorrhage, infection [sepsis], thrombotic pulmonary/other embolism, and pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders). 72 However, changes in the prevalence of these risk factors do not fully account for the increasing trends in severe maternal morbidity 73 and subsequent mortality among non-Hispanic Black women over time. 73

Examination of nonclinical factors, such as hospital quality 74 , 75 (the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes) and access to quality care, helps to explain some of the disparities in maternal mortality. Howell et al. 74 , 75 found that women from racial and ethnic minority groups give birth in lower quality hospitals and in hospitals with higher rates of severe maternal morbidity. Using a simulation model, they found that if non-Hispanic Black women gave birth at the same hospitals as non-Hispanic White women, the non-Hispanic Black severe maternal morbidity rate would decrease by 47.7%, from 4.2% to 2.9% (1.3 events per 100 deliveries per year). 74 , 76–79 Qualitative research reveals that many non-Hispanic Black women giving birth in low-performing hospitals experience poor patient–provider communication and difficulties in obtaining appropriate prenatal and postpartum care. 74 , 75

Additionally, homicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and postpartum, yet it remains understudied. Typically, homicide is not captured in examinations of pregnancy-related deaths or maternal mortality. Wallace et al. 80 argue that failure to identify and address factors underlying pregnancy-associated homicide will perpetuate racial inequity in mortality during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Mental Health

National epidemiological surveillance systems that capture information on health risk behaviors and mental health care access—including suicide attempts/occurrence, depression, anxiety, and clinical encounters that record concerns associated with mental health and substance abuse—have notable limitations. Measurement of race and gender across mental health studies varies considerably, creating a dearth of longitudinal research on the nuances of the mental health status of Black women. Even if the experiences of Black women as a racial–gender subgroup are captured with sufficient statistical power to report stratified results of survey findings ( Table 2 ), the results must be interpreted through the lens of the full scope of Black women's experiences in the United States.

Racial discrimination is a toxic “uncontrollable or unpredictable” stressor that is associated not only with poor physical health but also with psychological stress. 76–78 , 81 – 85 Chronic stressors reduce coping resources and increase vulnerability to mental health problems. 76 , 85 Non-Hispanic Blacks with higher levels of multiple stress measures are less likely to achieve intermediate or ideal levels of overall CV health. 86 Research suggests that chronic exposure to environmental stressors, such as racism, across the life span contributes to the weathering of the health of Black women, increasing their allostatic load and, consequently, compromising their reproductive health. 76 , 77 , 81–85 Allostatic load is a measure of the physiological dysregulation that results from cumulative chronic stress on the body. 76 , 87 It is a relevant measure for health disparities research because it can be utilized to assess racial/ethnic differences in biological responses to stressors and their relationship with adverse health outcomes. 83

Maternal mental health

Perceived stress from chronic experiences of discrimination has been found to be a significant predictor of poor birth outcomes. 76 Indeed, non-Hispanic Black women are twice as likely to have a low-birth weight infant than non-Hispanic White women. 76 Non-Hispanic Black women are at a disadvantage regarding the protective factor of the early initiation of prenatal care, with 67% participating in prenatal care in the first trimester compared with 77% of non-Hispanic White women and 81% of Asian women. 76 This is problematic, given that the delivery of perinatal mental health services is critical, particularly for non-Hispanic Black and Latina women because they experience higher rates of depression and anxiety during pregnancy and are at greater risk of poor pregnancy outcomes. 76 , 77 , 81–84 , 88 , 89 Perinatal depression has been linked to risks for adverse maternal and birth outcomes, including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, and low birth weight. 76 , 90–92 Specifically, it is estimated that up to 28% of non-Hispanic Black women experience perinatal depression. 89

Conclusions

The health of Black women is measured in their disproportionally poor health outcomes, but it is a result of a complex milieu of barriers to quality health care, racism, and stress associated with the distinct social experiences of Black womanhood in U.S. society. Black women are characterized by incredible resilience in the face of adversity and continue to experience improvements in health, even with the socioeconomic contexts that allow disparities to persist. Despite recent mandates by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to enhance the inclusion of women and racial/ethnic groups that are underrepresented in biomedical research in all NIH-funded research projects, 66 Black women continue to be underrepresented, 93–96 and the resulting interventions may not reflect the unique needs of Black women. Moreover, there is a dearth of current and accessible data on Black women that examines the diversity of Black women (nativity, ethnicity, and country of ancestry). Demographic and health data at the intersection of race and gender are critical to understanding the trends and opportunities for intervention and prevention.

Racism and gender discrimination have profound impacts on the well-being of Black women. Evidence-based care models that are informed by equity and reproductive justice frameworks (reproductive rights as human rights) 76 , 84 need to be explored to address disparities throughout the life course, including the continuum of maternity care, and to ensure favorable outcomes for all women. 79 Interventions to enhance patient–health care provider interactions include raising awareness about the implicit biases that a provider may hold. 97 Black women have continued to make significant inroads in many disciplines yet remain one of few demographic groups that must advocate for themselves to receive consistent and high-quality care. We have outlined disparities in several health conditions and the dire mortality outcomes experienced by Black women. Health does not exist outside its social context. Without equity in social and economic conditions, health equity is unlikely to be achieved, 98 and one cost of health inequality has been the lives of Black women.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their enormous gratitude to Dr. Beda Jean-Francois for her tireless work and feedback on this article.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Black Americans’ Views of and Engagement With Science

- 3. Black Americans’ views about health disparities, experiences with health care

Table of Contents

- Compared with other professions, fewer Black adults see people of their race at highest levels of success in science, engineering

- A majority of Black high school graduates recall a positive experience in STEM classes, but sizable shares also recall mistreatment

- Half or more Black Americans see mentors as especially influential to how many young people pursue STEM degrees

- Large majorities of Black adults have at least some trust in medical scientists or scientists, generally

- Black Americans generally hold positive views of medical researchers’ competence, skeptical of whether they own up to mistakes

- 75% of Black adults have heard about the Tuskegee study; a majority are skeptical that research procedures today will prevent serious misconduct

- About half of Black Americans say they’ve talked about the coronavirus outbreak multiple times a week

- Black Americans report mix of positive and negative reactions to science news, express frustration over political disagreements

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

- Appendix: Detailed charts and tables

CORRECTION (Jan. 12, 2024): Chapter 3 of a previous version of this report included an incorrect percentage because one survey question was asked only of women. Among Black adults, 55% say they have ever had at least one of six negative experiences with doctors or other health care providers.

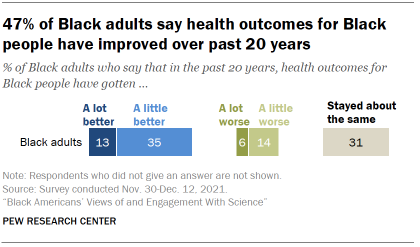

Black Americans offer a mixed assessment of the progress that has been made improving health outcomes for Black people: 47% say health outcomes for Black people have gotten better over the past 20 years, while 31% say they’ve stayed about the same and 20% think they’ve gotten worse.

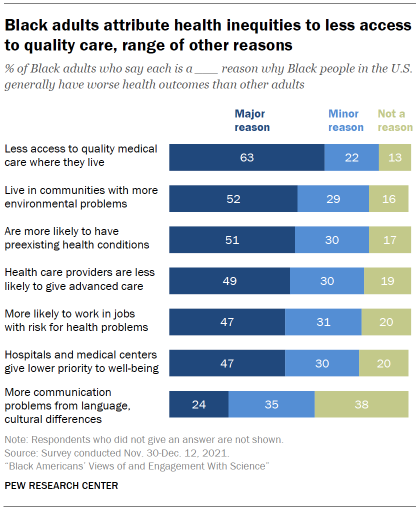

Less access to quality medical care is the top reason Black Americans see contributing to generally worse health outcomes for Black people in the U.S. Large shares also see other factors as playing a role, including environmental quality problems in Black communities, and hospitals and medical centers giving lower priority to the well-being of Black people.

Asked about their own health care experiences, most Black Americans have positive assessments of the quality of care they’ve received most recently. However, a majority (55%) say they’ve had at least one of six negative experiences, including having to speak up to get the proper care and being treated with less respect than other patients. (A seventh issue asked about applied only to women.)

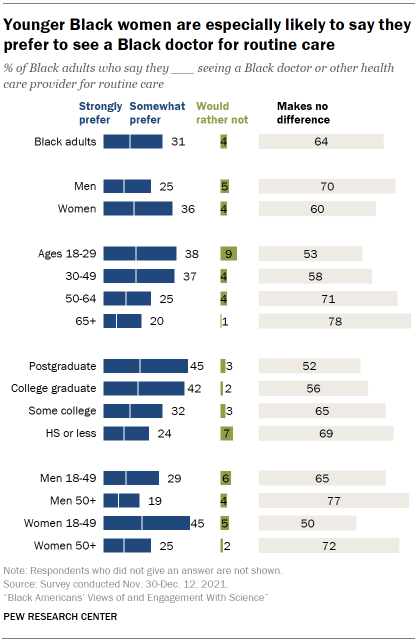

By and large, Black Americans do not express a widespread preference to see a Black health care provider for routine care: 64% say this makes no difference to them, though 31% say they would prefer to see a Black health care provider for care.

The experiences of younger Black women in the medical system stand out in the survey. A large majority of Black women ages 18 to 49 report having had at least one of seven negative health care experiences included in the survey. They are also more likely than other Black adults to say they would prefer a Black health care provider for routine care and to say a Black doctor or other health care provider would do a better job than medical professionals of other races and ethnicities at providing them with quality medical care.

Beliefs about key factors in health disparities for Black Americans

There are long-standing differences in health outcomes for Black people. Disproportionate mortalities from COVID-19 have heightened disparities between Black and other racial and ethnic populations in the U.S. The most recent estimates from the U.S. Census bureau projects life expectancy at 71.8 years for non-Hispanic Black Americans, the lowest since 2000 and below that estimated for other racial and ethnic groups. The White, non-Hispanic population experienced a smaller decline and, as a result, the gap between expected lifespans for Black and White Americans has widened in the past few years.

Experts have pointed to a number of contributing factors to disparities in health outcomes for Black Americans. The Center survey asked Black Americans for their own views about the reasons behind these disparities and their sense of whether there has been progress over time.

A majority of Black adults say less access to quality medical care where they live is a major reason why Black people in the U.S. generally have worse health outcomes than other adults. About two-in-ten (22%) say this is a minor reason, while just 13% say it is not a reason.

Black adults see a range of other factors – including environmental problems and less-advanced care from health care providers – as contributing to worse health outcomes for Black adults, though somewhat smaller shares cite these as major reasons than point to access issues.

About half (51%) say a major reason why Black people generally have worse health outcomes than others is because they are more likely to have preexisting health conditions. Issues with home and work environments also are seen as playing a role: 52% say a major reason why Black people have worse health outcomes than others is because they live in communities with more environmental problems that cause health issues; 47% say a major reason is that Black people are more likely to work in jobs that put them at risk for health problems.

The health care system is also seen as contributing to the problem: 49% say a major reason why Black people generally have worse health outcomes is because health care providers are less likely to give Black people the most advanced medical care. A roughly equal share (47%) says hospitals and medical centers giving lower priority to their well-being is a major reason for differing health outcomes.

A smaller share (24%) views communication problems from language or cultural differences as a major reason why Black people generally have worse health outcomes than other adults in the U.S.

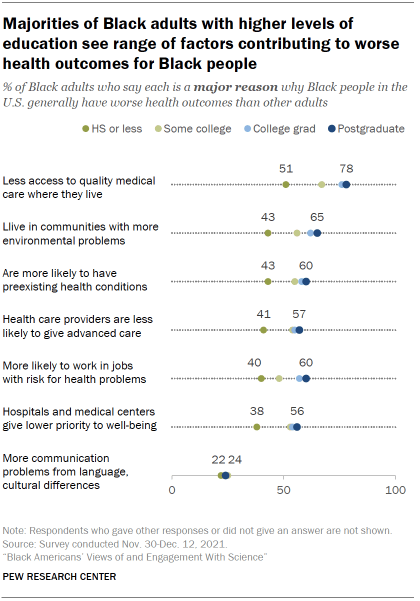

Black adults with higher levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels of education to point to a variety of factors as major reasons for worse health outcomes among Black people.

For instance, large majorities of Black postgraduates (78%) and college graduates (76%) say less access to quality medical care is a major reason Black people have worse health outcomes than other adults in the U.S., compared with 67% of those with some college experience and 51% of Black adults with a high school diploma or less education.

There are also differences in views by age. A majority of Black adults ages 50 and older (58%) say that being more likely to have preexisting health conditions is a major reason why Black people have worse health outcomes than others. Fewer of those under age 50 (46%) see this as a major reason.

Conversely, younger Black adults are more likely than older adults to cite actions from hospitals and medical centers: 50% of those under age 50 say hospitals and medical centers giving lower priority to their well-being is a major reason why Black people have worse health outcomes; 43% of Black adults 50 and older say the same.

Overall, 47% think health outcomes for Black people have gotten a lot or a little better over the last 20 years. Still, 31% say they have stayed about the same and 20% think they have gotten a lot or a little worse.

For the most part, Black adults’ views on this question are fairly similar across characteristics such as age, gender and levels of educational attainment.

A majority of Black Americans give positive ratings of their recent health care, but can also point to negative experiences in the past

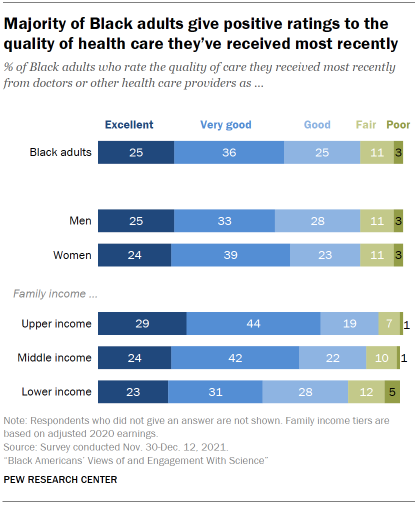

Black adults have generally positive impressions of their most recent experience with health care. A majority (61%) rate the quality of care they’ve received from doctors or other health care providers recently as excellent (25%) or very good (36%). A quarter describe the quality as good, while just 11% say it was fair and only 3% describe the quality of care they’ve received most recently as poor. These ratings are nearly identical to those of all U.S. adults.

Those with higher incomes report more positive recent experiences with doctors and other health care providers than do those with lower incomes.

When it comes to cost, 51% of Black adults describe the out-of-pocket cost of their most recent medical care as ‘about what is fair.’ About a quarter (27%) say they paid more than what’s fair, while 19% say they paid less than what’s fair. For more details, see the Appendix .

A majority of Black adults report at least one negative interaction with doctors and other health care providers at some point in the past

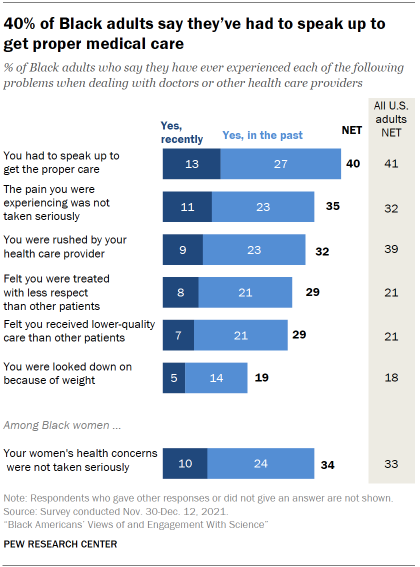

While Black adults generally offer positive ratings of the quality of care they’ve received most recently, a majority (55%) say they’ve had at least one of six negative experiences with doctors or other health care providers at some point in their lives. (A seventh issue asked about applied only to women.)

Overall, 40% of Black adults say they have had to speak up to get the proper care either recently (13%) or in the past (27%). This is the most frequently cited negative experience with medical care across the items included in the survey.

One focus group respondent described their experience this way:

“I had a situation where I had to go through about two different doctors until I was able to get the results that I was requesting, because they did not believe that the issues that I had were valid, or that they were as serious as I made them out to be. It’s kind of been an ongoing thing, so I’m always leery when I’m talking to physicians. I don’t trust them just because they are doctors. I know they have the Hippocratic Oath, but it feels like it’s a little different when they deal with African American patients. And I don’t care if it’s an African American physician or White physicians.” – Black woman, 25-39

When it comes to treatments for pain, 35% of Black adults say they’ve felt the pain they were experiencing was not taken seriously either recently (11%) or in past interactions (23%) with doctors and other health care providers.

About three-in-ten Black adults (32%) say they’ve felt rushed by their health care provider and 29% say they’ve felt they were treated with less respect than other patients, either recently or in past experiences with doctors and other health care providers. Similarly, 29% say they’ve felt they’ve received lower quality medical care at some point; 70% of Black adults say this has not happened to them.

Relatively fewer (19%) say they’ve been looked down on because of their weight or eating habits; 79% say this hasn’t happened to them.

Among Black women, 34% say their women’s health concerns or symptoms were not taken seriously in interactions with doctors and other health care providers.

Black adults at all family income levels are about equally likely to report having at least one of these experiences.

The frequency of negative experiences with the health care system are mostly similar between Black adults and all U.S. adults. However, greater shares of Black adults than all U.S. adults say they’ve felt they’ve received lower-quality care (29% vs. 21% of all U.S. adults) or been treated with less respect than other patients (29% vs. 21%). And fewer Black adults say they were rushed by a health care provider (32% vs. 39% of all U.S. adults).

Black women, especially younger Black women, stand out for the frequency with which they report having had negative health care experiences. Taken together, 63% of Black women say they’ve experienced at least one of the seven negative health care experiences measured in the survey. Among Black men, 46% say they’ve had at least one of six negative experiences with doctors or other health care providers. Black women were asked one more item than men, but the gap between men and women on the six experiences in common is almost identical (62% vs. 46%).

In their own words: Focus group participants on difficulties getting treatment for pain management

There are long-standing concerns about racial biases in pain management. A study in 2020 of emergency room patients experiencing acute appendicitis found wide racial disparities in pain management for both children and adults. The growing use of artificial intelligence algorithms to determine a patient’s need for pain management is raising new questions about how to address systematic bias in pain management treatments.

Here are a few of the comments from focus group participants about getting treatment for pain.

“Well, my husband’s condition (trigeminal neuralgia), it requires a narcotic. And before we got [to current health care provider] for so long, a lot of people just assumed that he was a junkie, like he was just coming in and trying to get pain medication and they wanted to put him on this rotation that just didn’t work, wanted him to take this Tylenol. And it was so frustrating.” – Black woman, age 25-39

“My mom, and I can’t think of it specifically, she has complained to me about being at the hospital and feeling as though they were treating her like she was a drug addict. When they would have to give her pain medication, or she would need something for pain – having her fill out forms, only allotting a certain amount, or cutting it, when her pain is … she goes through pain more times a day, they’ll cut it to less. Less than what she needs to get through the day and not be in pain.” – Black man, age 25-39

“At what point are you going to educate your nurses, your doctors, your ER team that, ‘Hey, this is the protocol when we have sickle cell’? Now, the ironic thing is, when she was going to the children’s hospital, they did have a sickle cell protocol and their treatment of their kids was a little bit different. Most of the time, … 85% of the time … because they were kids, they took their word for it. But when they transitioned over to the adult care, it’s terrible. It’s terrible with the pain, it’s terrible with pain management.” – Black woman, age 40-65

“I was in pain, like in my abdomen. Come to find out I had a fibroid. But I went to the emergency room. ‘Oh, no. You’re fine.’ Something like, ‘Your insurance won’t cover this emergency visit’ or something. ‘Just go to Walgreens and get some Tylenol.’ And I’m like, ’I’m in severe pain. Like I have abdominal pain.’ I ended up going to my doctor, the one I eventually found. He ended up getting me an ultrasound. We did blood work. It was just totally different.” – Black woman, age 25-39

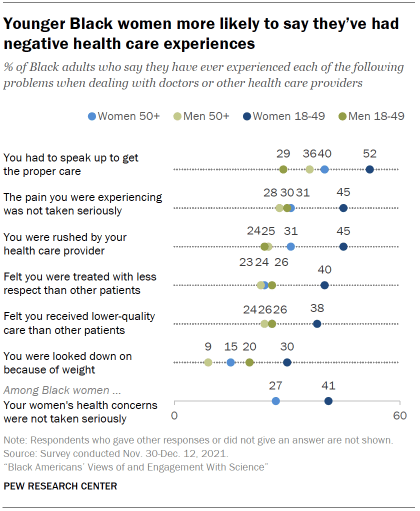

A large majority of younger Black women ages 18 to 49 report negative interactions with health care providers: 71% say they’ve had at least one negative experience in the past. By comparison, a smaller share of Black women ages 50 and older say this (54%).

Among Black men, differences by age are more modest than among women, and the pattern runs in the opposite direction: 51% of men ages 50 and older report experiencing at least one of six negative experiences with health care providers, compared with a somewhat smaller share of men ages 18 to 49 (43%).

The experiences of younger Black women stand out across each individual item on health care interactions. For instance, 52% of younger Black women say they’ve had to speak up to get the proper care, compared with 40% of older women, 36% of older men and 29% of younger men.

Among U.S. adults, women ages 18 to 49 are also more likely than older women or than men to say they have had at least one of these negative experiences in a health care visit.

31% of Black adults say they would prefer to see a Black health care provider; a majority have no preference

The share of Black adults working in health-related jobs is roughly equal to their share in the overall workforce, although just 5% of physicians and surgeons are Black. The new survey asked people for their preferences and thoughts about what, if any, difference it makes to have a health care provider who shares their racial background.

Overall, 31% of Black adults say they would strongly (14%) or somewhat prefer (17%) to see a Black doctor or other health care provider for routine medical care. About two-thirds (64%) say it makes no difference to them, and just 4% say they’d rather not do so for routine care.

Younger Black women stand out from their elders and from Black men in their preferences for seeing a Black health care provider.

Among Black women, a much greater share of those ages 18 to 49 than those 50 and older say they’d prefer to see a Black health care provider for routine care (45% vs. 25%). A majority of older Black women (72%) say it wouldn’t make a difference to them.

There’s a similar pattern in views among Black men, though the gap between younger and older Black men is not as large as among Black women: 29% of Black men ages 18 to 49 would prefer to see a Black health care provider for routine care, compared with 19% of Black men ages 50 and older.

There’s hardly any difference in views on this question between those who have seen a Black doctor or health care provider in the past and those who have not. Among the roughly two-thirds of Black adults who say they’ve seen a Black health care provider for routine care in the past, 32% say they would prefer to see a Black health care provider; among those who have not seen a Black health care provider previously, 30% express this view. See the Appendix for details .

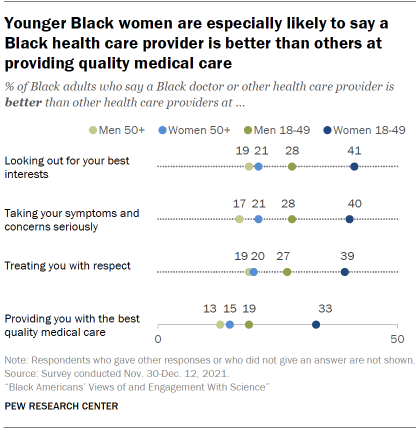

Younger Black women are more likely to see benefits for the quality of medical care from health care treatment with same-race providers

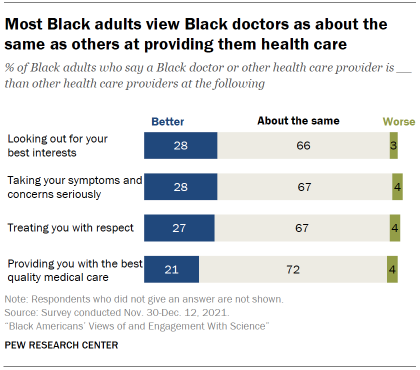

When it comes to key aspects of medical care, majorities of Black adults view a Black doctor and other health care providers as about the same as providers who do not share their race or ethnicity at meeting their needs.

For instance, 72% of Black adults think a Black health care provider is about the same as other health professionals when it comes to the quality of medical care they provide; 21% think a Black health care provider is better than others at this, while just 4% say worse.

Roughly two-thirds view a Black health care provider as about the same as others when it comes to taking their symptoms and concerns seriously, treating them with respect, and looking out for their best interests. Roughly three-in-ten see a Black doctor or health care professional as better than other providers for each of these elements of care.

Among the 31% of Black Americans who say they would prefer to see a Black health care provider for routine matters, majorities think a Black health care provider is better than others at looking out for their best interests (64%), taking their symptoms seriously (64%), treating them with respect (60%) and providing the best quality medical care (53%).

It is unclear whether personal experience lies behind these beliefs. Black adults who have seen a Black health care provider in the past hold similar views on this as those who have not. See Appendix for more details .

Younger Black women are more inclined than older women and men to see an advantage from routine care with a Black health care provider. Still, the majority viewpoint across groups – including among younger Black women – is that a Black health care provider is about the same as others at providing key aspects of care.

About four-in-ten Black women ages 18 to 49 (41%) say a Black health care provider is better than others at looking out for their best interests, compared with 53% who say they are about the same as other health care providers.

Smaller shares of Black women ages 50 and older (21%), Black men 18 to 49 (28%) and Black men ages 50 and older (19%) view a Black health care provider as better than others at looking out for their best interests. Majorities say they are about the same as others at this.

Age and gender patterns among Black adults are similar across the other aspects of care included in the survey.

When it comes to education, Black adults with higher levels of education tend to be more likely to view a Black doctor or health care provider as better than others when it comes to these key aspects of care. But as with patterns by age and gender, the majority view across levels of educational attainment remains that a Black health care provider is about the same as other healthcare professionals at providing routine health and medical care. See the Appendix for details.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Black Americans

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & Science

- COVID-19 in the News

- Medicine & Health

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

- Science News & Information

- STEM Education & Workforce

- Trust in Science

A look at Black-owned businesses in the U.S.

8 facts about black americans and the news, black americans’ views on success in the u.s., among black adults, those with higher incomes are most likely to say they are happy, fewer than half of black americans say the news often covers the issues that are important to them, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 100

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Post- Dobbs Challenges in Research and Patient Protections

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York

- 2 Division on Substance Use Disorders, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York

- 3 Division of Alcohol, Drugs and Addiction, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts

- 4 Division of Women’s Mental Health, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts

- 5 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

The US Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June 2022 asserted abortion is not a protected right under the US Constitution, overruling 50 years of reproductive autonomy since Roe v Wade . The legality of abortion now falls to individual states, creating an irregular and ambiguous patchwork of regulations and an evolving landscape in which to navigate health care. While the Dobbs decision has far-reaching implications for reproductive health care in the US, it also has significant implications for conducting substance use and other clinical research. There have been other precedents affecting public health decided by a single branch of the federal government, in this case the judicial branch, such as access to firearms and suicide death. 1 The Dobbs decision endangers gains made over the last several decades to increase representation of women, gender-diverse people, and chronically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in clinical research. Lack of diversity of research participants limits generalizability of medical knowledge and subsequent health benefits for these communities, 2 which can, in turn, exacerbate health disparities. Investigators need to carefully monitor the changing reproductive health legal landscape in the context of state laws to ensure continued participation of women and other people who can become pregnant, while simultaneously maintaining privacy and protection of research participants.

Read More About

Campbell ANC , Greenfield SF. Post- Dobbs Challenges in Research and Patient Protections. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online April 24, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0598

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Psychiatry in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education