Find anything you save across the site in your account

The True Meaning of Nostalgia

By Michael Chabon

I recently had a brief chat with a hundred-year-old Jew. His name is Manuel Bromberg, and he's a resident of Woodstock, New York. Mr. Bromberg had written me a letter, to tell me that he had read and liked my latest book, and in the letter he mentioned that in a few days he would be hitting the century mark, so I thought I'd call him up and wish him a happy hundredth.

An accomplished artist and professor for most of his very long life, Mr. Bromberg painted murals for the W.P.A. and served as an official war artist for the U.S. Army during the Second World War, accompanying the Allied invasion of Europe with paints, pencils, and sketch pad, his path smoothed and ways opened to him by the presence in his pocket of a pass signed by General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself, just like the Eisenhower pass carried by “my grandfather,” the nameless protagonist of my novel . After the war, this working-class boy from Cleveland rode the G.I. Bill to a distinguished career as a serious painter, sculptor, and university professor.

Mr. Bromberg sounded strong and thoughtful and sharp as a tack on the other end of the line, his voice in my ear a vibrant connection not just to the man himself but to the times he had lived through, to the world he was born into, a world in which the greater part of Jewry lived under the Czar, the Kaiser, and the Hapsburg Emperor, in whose army Adolf Hitler was a corporal. As we chatted, I realized that I was talking to a man almost exactly the same age as my grandfather, were he still alive—I mean my real grandfather, Ernest Cohen, some of whose traits, behaviors, and experiences, along with those of his brothers, brothers-in-law, and other men of their generation in my family, of Mr. Bromberg’s generation, helped me to shape the life and adventures of the hero of that book, as my memories of my grandmothers and their sisters and sisters-in-law helped shape my understanding of that book's “my grandmother.”

Then Mr. Bromberg mentioned that he had now moved on to another novel of mine, “ The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay ,” and he wanted to tell me about another connection between his life and the world of my books: when he was in junior high, in Cleveland, Ohio, his chief rival for the title of School's Most Talented Artist was a four-eyed, acne-faced wunderkind named Joe Shuster. One day in the mid-nineteen-thirties, in the school locker room, Mr. Bromberg told me, Joe Shuster came to him looking for his opinion on some new drawings: pencil sketches of a stylized cartoon strongman cavorting in a pair of circus tights, with a big letter-S insignia on his chest. To the young Mr. Bromberg, they seemed to be nothing more than competent figure drawings, but Shuster seemed to be very excited about this “Superman” character that he and a friend had come up with. “I have to be honest with you, Michael,” Mr. Bromberg told me, in a confidential tone. “I was not impressed.”

After we talked, I found myself reflecting on the way that, with his Eisenhower pass and his connection to the golden age of comic books, with his creative aspirations rooted equally in hard work and the highbrow, in blue collar and the avant-garde, Mr. Bromberg had been able to find so much of himself in my writing, as so many Mr. Brombergs, in various guises, can be found in the pages of my books. I think there are a few reasons that the lives of that generation of American Jews have formed my fiction. The first is that I have always been—to a fault, it has at times seemed—a good boy. At family gatherings, at weddings and bar mitzvahs, from the time I was small, among all my siblings and cousins, I always felt a sense of dutifulness about hanging out with the old people, enduring their interrogations, remedying their ignorance of baffling modern phenomena, such as Wacky Packages or David Bowie, and, above all, listening to their reminiscences. As the extent of my sense of obligation about serving this function became apparent, I was routinely left behind with the Aunt Ruths and the Uncle Jacks and the Cousin Tobys, not just by my peers and coevals but by our parents _,_ too. Even to this day, at the weddings and bar mitzvahs of other families, you will often find me sitting alone at a table with an Uncle Jack completely unrelated to me, patiently listening to the story of the plastic-folding-rain-bonnet business he started in Rochester in 1948 with a three-hundred-dollar loan from somebody else's Aunt Ruth, a story that all of his own relatives tired of hearing years ago, if they ever paid attention at all.

The dutifulness of a good boy is not, of course, the whole explanation. I'm not that good. The thing is, I have always wanted to hear the stories, the memories, the remembrances of vanished Brooklyn, or vanished South Philly, or even, dim and sepia-toned and far away, vanished Elizavetgrad, vanished Vilna. I have always wanted to hear the stories of lost wonders, of how noon was turned dark as night by vast flocks of the now-extinct passenger pigeon, of Ebbets Field and five-cent all-day Saturday matinées and Horn & Hardart automats, and I have always been drawn to those rare surviving things—a gaudy Garcia y Vega cigar box, a lady swimming in a rubber bathing cap covered in big rubber flowers, Mr. Bromberg—that speak, mutely or eloquently, of a time and a place and a generation that will soon be gone from the face of the earth.

My work has at times been criticized for being overly nostalgic, or too much about nostalgia. That is partly my fault, because I actually have written a lot about the theme of nostalgia; and partly the fault of political and economic systems that abuse nostalgia to foment violence and to move units. But it is not nostalgia’s fault, if fault is to be found. Nostalgia is a valid, honorable, ancient human emotion, so nuanced that its sub-variants have names in other languages—German's sehnsucht , Portuguese's saudade —that are generally held to be untranslatable. The nostalgia that arouses such scorn and contempt in American culture—predicated on some imagined greatness of the past or inability to accept the present—is the one that interests me least. The nostalgia that I write about, that I study, that I feel, is the ache that arises from the consciousness of lost connection.

More than ten years ago now, my cousin Susan, a daughter of my mother's Uncle Stanley, forwarded me some reminiscences of Stanley’s childhood that he had set down just as his health was failing. Besides my grandfather, Uncle Stan was always my favorite among the male relatives of that generation: witty, charming, and refined, with a deceptively sweet and gentle way of being sardonic and even, on occasion, sharp-tongued. He was a professor, a scholar of medieval German who for many years was also the dean of humanities at the University of Texas. A Guggenheim fellow and Fulbright scholar, Stan was fluent in a number of languages, not least among them Yiddish; during his tenure as dean he created a Yiddish-studies program at U.T. He had been an intelligence officer in Italy during the Second World War, and was decorated for his service during the fierce battle of Monte Cassino.

His reminiscences—or fragmentary memoir, as I came to think of it—ignored all that. It was a delightful document, all too brief, a shaggy and rambling but vivid account of his early life as the son of typical Jewish-immigrant parents, in Philadelphia and Richmond. It featured memories of the godlike lifeguards and the Million-Dollar Pier, at Atlantic City; of stealing turnips and playing Civil War, in Richmond, with boys who were the grandsons of Confederate soldiers; of neighbors who brewed their own beer during Prohibition; of his father’s numerous unlucky business ventures; of his mother hauling wet laundry up from the basement to hang it out on the line, where, in the wintertime, it froze solid.

But what stood out for me most vividly in Uncle Stanley's memories was the omnipresence and the warmth of his memories of his many aunts, uncles, and cousins, who seemed to take up as much room in his little memoir as his siblings and parents. In the geographically and emotionally close world they lived in, Stan’s extended family of parents’ siblings, their spouses and their siblings and their spouses, and, apparently, huge numbers of first, second, third, and more distant cousins, was just that—an all but seamless extension of the family he lived in. That’s how it was in those days. Somebody came to Philadelphia from Russia, and then his brother came, and then another brother, and pretty soon there were fifty people living in the same couple of neighborhoods in Philly, a kind of community within the community, connected not merely by blood or ties of affection but also by the everyday commitments, debts, responsibilities, disputes, tensions, and small pleasures that make up the daily life of a family.

When I was growing up, it wasn’t like that anymore. My parents moved seven times before I was seven years old, back and forth across the country. I had a lot of second cousins and great-aunts and great-uncles, and I used to see them—and be abandoned to their company—at weddings, bar mitzvahs, et cetera. Listening to those stories, I always felt a kind of a lack, a wistfulness, a sense of having missed something. Reading Stan’s memoir, looping and wandering as his thoughts were as he lay contending with his illness, seemed to connect me, briefly but powerfully, to all that vanished web of connections.

Nostalgia, to me, is not the emotion that follows a longing for something you lost, or for something you never had to begin with, or that never really existed at all. It's not even, not really, the feeling that arises when you realize that you missed out on a chance to see something, to know someone, to be a part of some adventure or enterprise or milieu that will never come again. Nostalgia, most truly and most meaningfully, is the emotional experience—always momentary, always fragile—of having what you lost or never had, of seeing what you missed seeing, of meeting the people you missed knowing, of sipping coffee in the storied cafés that are now hot-yoga studios. It’s the feeling that overcomes you when some minor vanished beauty of the world is momentarily restored, whether summoned by art or by the accidental enchantment of a painted advertisement for Sen-Sen, say, or Bromo-Seltzer, hidden for decades, then suddenly revealed on a brick wall when a neighboring building is torn down. In that moment, you are connected; you have placed a phone call directly into the past and heard an answering voice.

“Thank you, Mr. Bromberg,” I said, just before I hung up, not sure what I was thanking him for, exactly, but overcome with gratitude all the same, both of us aware, I suppose, as we made tentative plans to meet sometime soon, or at least to talk again, that the next time I called there might be no one on the other end of the line.

Adapted from the author’s remarks to the Jewish Book Council, upon receiving the organization’s Modern Literary Achievement award, on March 7th.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Cody Delistraty

By Roz Chast

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Nostalgia—How to Enjoy Reflecting on the Past

and how to deal with the negative effects of being too nostalgic.

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Dr. Sabrina Romanoff, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a professor at Yeshiva University’s clinical psychology doctoral program.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SabrinaRomanoffPhoto2-7320d6c6ffcc48ba87e1bad8cae3f79b.jpg)

Klaus Vedfelt / Getty Images

Nostalgia Used to Be Considered a Neurological Illness

Examples of nostalgia from popular culture, types of nostalgia, benefits of being nostalgic.

- Can You Be Too Nostalgic?

How to Avoid the Negative Effects of Nostalgia

Nostalgia is a sentimentality for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations. Nostalgia is usually triggered by something reminding an individual of an experience from the past. It is often characterized as a longing or desire to return to a former time or place.

Nostalgia can also be thought of as "the memory of happiness," as it is often associated with happy memories from the past. It can be a source of comfort in times of sadness or distress.

However, nostalgia is not just about happy memories; it can also be about longing for a time when things were simpler, or for a time when we felt more connected to others.

Press Play to Learn What the Sentimental Items You Keep Say About You

Hosted by Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how to determine what your sentimental items say about you. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts / Amazon Music

Nostalgia is a relatively new concept. The word was first coined in 1688 by Swiss physician Johannes Hofer, who defined it as a neurological illness of continually thinking about one's homeland and longing for return.

It was not until the 19th century that nostalgia began to be seen as a positive sentiment, rather than a pathological condition. Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, for example, saw nostalgia as a way of reconnecting with our past and understanding our present. For Jung, nostalgia was a way to access the " collective unconscious "—the shared history and experiences that we all have as human beings.

During the First World War, nostalgia was once again associated with illness, as soldiers away at battle longed for the comforts of home. However, after the war ended, nostalgia once again became a positive sentiment.

There are many examples of nostalgia in popular culture. The film It's a Wonderful Life (1946) is often cited as one of the most nostalgic films ever made. The film tells the story of George Bailey (played by Jimmy Stewart), a man who is considering suicide on Christmas Eve.

However, he is visited by an angel who shows him how different his life, and the lives of those around him, would have been if he had never been born. The film's sentimental portrayal of small-town life in the early 20th century has helped to make it a holiday classic.

The television series The Wonder Years (1988-1993) is another example of nostalgia. The show tells the story of Kevin Arnold (played by Fred Savage), a boy growing up in the suburbs in the 1960s and 1970s. The show is notable for its use of voice-over narration from Kevin's older self, which gives the show a nostalgic feeling.

The song "I Will Always Love You" by Whitney Houston (originally released in 1992) is often cited as a nostalgic song. The song was written by Dolly Parton and is about a woman who is leaving her lover. However, she promises to always love him, even though they are no longer together. The song's sentimental lyrics and melody have helped to make it one of the most popular love songs of all time.

There are two types of nostalgia: positive and negative.

- Positive nostalgia is characterized by happy, rose-tinted memories of the past. It is often associated with feelings of warmth, happiness, and comfort.

- Negative nostalgia , on the other hand, is characterized by bittersweet or even painful memories of the past. It is often associated with longing, sadness, and regret.

Nostalgia can also be divided into three different categories: personal, social, and cultural.

- Personal nostalgia is characterized by memories of specific people or events from one's own life.

- Social nostalgia is characterized by memories of a time when one felt more connected to others.

- Cultural nostalgia is characterized by memories of a time when one felt more connected to their culture.

Nostalgia has been shown to have a number of benefits. For example, nostalgia has been shown to:

- Increase self-esteem

- Provide a sense of social support

- Help people to cope with difficult life transitions, such as divorce, retirement, and death

Nostalgia can also have positive effects on physical health. For example, nostalgia has been shown to boost immune function and reduce stress levels. Nostalgia can also help to increase life satisfaction and reduce anxiety.

Can You Be Too Nostalgic?—Negative Effects

However, nostalgia can also have negative effects. For example, nostalgia can:

- Lead to a sense of loneliness and isolation

- Cause people to dwell on the past and become unhappy with the present

- Make people less likely to take action in the present

There are a few things you can do to avoid the negative effects of nostalgia:

- Think about the present moment . What are you doing right now that you enjoy?

- Make an effort to connect with others in the present. Spend time with people you care about. Talk to them about your positive memories.

- Do things that make you happy . Listen to music, go for walks, watch your favorite movie.

- Talk to a therapist . If you're feeling particularly down, talking to a therapist can help.

- Be mindful. Be aware of how much time you spend dwelling on the past.

The Atlantic. When Nostalgia Was a Disease .

Battesti M. Nostalgia in the Army (17th-19th Centuries) . Front Neurol Neurosci . 2016;38:132-142. doi:10.1159/000442652

Batcho KI. Nostalgia: The bittersweet history of a psychological concept . Hist Psychol . 2013;16(3):165-176. doi:10.1037/a0032427

National Endowment for the Arts. Did You Know.... It's a Wonderful Life edition .

Biography. 10 Things You May Not Know About the Wonder Years .

Whitney Houston. Whitney Houston ‘I Will Always Love You’ #1 In 1992

Abeyta AA, Routledge C, Kaslon S. Combating Loneliness With Nostalgia: Nostalgic Feelings Attenuate Negative Thoughts and Motivations Associated With Loneliness . Front Psychol . 2020;11:1219. Published 2020 Jun 23. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01219

Newman DB, Sachs ME. The Negative Interactive Effects of Nostalgia and Loneliness on Affect in Daily Life . Front Psychol . 2020;11:2185. Published 2020 Sep 2. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02185

Jiang T, Cheung WY, Wildschut T, Sedikides C. Nostalgia, reflection, brooding: Psychological benefits and autobiographical memory functions . Conscious Cogn . 2021;90:103107. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2021.103107

Ismail S, Christopher G, Dodd E, et al. Psychological and Mnemonic Benefits of Nostalgia for People with Dementia . J Alzheimers Dis . 2018;65(4):1327-1344. doi:10.3233/JAD-180075

Juhl J, Wildschut T, Sedikides C, Xiong X, Zhou X. Nostalgia promotes help seeking by fostering social connectedness . Emotion . 2021;21(3):631-643. doi:10.1037/emo0000720

Batcho KI. Nostalgia: retreat or support in difficult times? . Am J Psychol . 2013;126(3):355-367. doi:10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.3.0355

Newman DB, Sachs ME, Stone AA, Schwarz N. Nostalgia and well-being in daily life: An ecological validity perspective . J Pers Soc Psychol . 2020;118(2):325-347. doi:10.1037/pspp0000236

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Emotions & Feelings — Nostalgia

Essays on Nostalgia

Nostalgia is a powerful emotion that can transport us back to cherished memories and moments from the past. It can be a great topic for an essay, as it allows us to explore our emotions and experiences in a meaningful way. Whether you want to write about the impact of nostalgia on our lives or dive into specific memories and their significance, there are endless possibilities for exploring this theme.

When choosing a topic for an essay on nostalgia, consider what aspects of the emotion resonate with you the most. Are you drawn to the idea of exploring the role of nostalgia in shaping our identities, or do you want to focus on a specific nostalgic experience from your own life? You could also consider analyzing the cultural significance of nostalgia, or even its impact on mental health and well-being.

For an argumentative essay on nostalgia, you might consider topics such as "The Role of Nostalgia in Shaping Personal Identity" or "The Cultural Importance of Nostalgia in Art and Media." For a cause and effect essay, topics like "The Effects of Nostalgia on Mental Health" or "How Nostalgia Shapes Our Decision-Making Process" could be compelling. If you're interested in writing an opinion essay, topics such as "Why Nostalgia Is a Universal Emotion" or "The Dangers of Living in the Past" could spark interesting discussions. Finally, for an informative essay, topics like "The History of Nostalgia as a Concept" or "The Psychological Mechanisms Behind Nostalgia" could provide rich material to explore.

For a thesis statement on nostalgia, consider statements like "Nostalgia serves as a powerful force in shaping our personal narratives and sense of self" or "Nostalgia can have both positive and negative effects on our emotional well-being." When writing an to a nostalgia essay, you could begin by evoking a specific nostalgic memory, exploring its significance, and setting the stage for the themes you'll explore. In a , you might reflect on the broader implications of your exploration of nostalgia, tying together the themes you've discussed and leaving the reader with a sense of closure and insight.

Myne Owne Land Analysis

My significant place: my family's mountain cabin, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Joan Didion's "On Going Home"

Nostalgia of my childhood years, investigation of the idea of nostalgia in people's lifes, the benefits of reminiscing: personal experience, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Nostalgia as a Form of Escapism in Contemporary Art and Design

The disclosure of nostalgia in carol ann duffy's poem, analysis of the term nostalgia and its manifestation in real life, how an aesthetic can induce nostalgia, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Way Supermarkets Use Seasonality to Influence Nostalgic Feelings

Against meat by j. safran: the importance of the ability to reminisce, use of the concept of nostalgia by creators of animated content, memories about apartheid in native nostalgia by jacob dlamini, the way phenomenon of nostalgia is shown in books and films, nostalgia in the great gatsby, same drugs song analysis, relevant topics.

- Responsibility

- Forgiveness

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Blue Boat (1892) by Winslow Homer. Courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Nostalgia reimagined

Neuroscience is finding what propaganda has long known: nostalgia doesn’t need real memories – an imagined past works too.

by Felipe De Brigard + BIO

He was still too young to know that the heart’s memory eliminates the bad and magnifies the good, and that thanks to this artifice we manage to endure the burden of the past. But when he stood at the railing of the ship and saw the white promontory of the colonial district again, the motionless buzzards on the roofs, the washing of the poor hung out to dry on the balconies, only then did he understand to what extent he had been an easy victim to the charitable deceptions of nostalgia. – From Love in the Time of Cholera (1985) by Gabriel García Márquez

The other day I caught myself reminiscing about high school with a kind of sadness and longing that can only be described as nostalgia. I felt imbued with a sense of wanting to go back in time and re-experience my classroom, the gym, the long hallways. Such bouts of nostalgia are all too common, but this case was striking because there is something I know for sure: I hated high school. I used to have nightmares, right before graduation, about having to redo it all, and would wake up in sweat and agony. I would never, ever like to go back to high school. So why did I feel nostalgia about a period I wouldn’t like to relive? The answer, as it turns out, requires we rethink our traditional idea of nostalgia.

Coined by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688, ‘nostalgia’ referred to a medical condition – homesickness – characterised by an incapacitating longing for one’s motherland. Hofer favoured the term because it combined two essential features of the illness: the desire to return home ( nostos ) and the pain ( algos ) of being unable to do so. Nostalgia’s symptomatology was imprecise – it included rumination, melancholia, insomnia, anxiety and lack of appetite – and was thought to affect primarily soldiers and sailors. Physicians also disagreed about its cause. Hofer thought that nostalgia was caused by nerve vibrations where traces of ideas of the motherland ‘still cling’, whereas others, noticing that it was found predominantly among Swiss soldiers fighting at lower altitudes, proposed instead that nostalgia was caused by changes in atmospheric pressure, or eardrum damage from the clanging of Swiss cowbells. Once nostalgia was identified among soldiers from various nationalities, the idea that it was geographically specific was abandoned.

By the early 20th century, nostalgia was considered a psychiatric rather than neurological illness – a variant of melancholia. Within the psychoanalytic tradition, the object of nostalgia – ie, what the nostalgic state is about – was dissociated from its cause. Nostalgia can manifest as a desire to return home, but – according to psychoanalysts – it is actually caused by the traumatic experience of being removed from one’s mother at birth. This account began to be questioned in the 1940s, with nostalgia once again linked to homesickness. ‘Home’ was now interpreted more broadly to include not only concrete places, such as a childhood town, but also abstract ones, such as past experiences or bygone moments. While disagreements lingered, by the second part of the 20th century, nostalgia began to be characterised as involving three components. The first was cognitive : nostalgia involves the retrieval of autobiographical memories. The second, affective : nostalgia is considered a debilitating, negatively valenced emotion. And third, conative : nostalgia comprises a desire to return to one’s homeland. As I’ll argue, however, this tripartite characterisation of nostalgia is likely wrong.

First, two clarifications: nostalgia is neither pathological nor beneficial. I’ve always found it surprising when scholars fail to note the patent contradiction in illustrating nostalgia’s debilitating nature with the example of Ulysses in the Odyssey . Homer tells us that thinking of home was painful and brought tears to Ulysses’ eyes, yet the thought of going back to Ithaca wasn’t incapacitating. Instead, it was motivating. That it took Ulysses 10 years to get back home had more to do with Circe, Calypso and Poseidon than with the debilitating nature of nostalgia. The other clarification: philosophers distinguish the object and the content of a mental state. The object is what the mental state is about; it needn’t exist – I can think of Superman, for instance. The content is the way in which the object is thought of. The same object can be thought of in different ways – Lois Lane can think of Kal-El as either Superman or Clark Kent – and thus bring about different, even contradictory, thoughts about the same object (here, I assume that contents are instantiated in neural representations suitably related to their objects).

W ith these clarifications in mind, let’s re-evaluate the tripartite view of nostalgia, beginning with its cognitive component. According to this view, nostalgia involves autobiographical memories of one’s homeland, suggesting that the object of one’s nostalgic states must be a place. However, research shows that by ‘homeland’ people often mean something else: childhood experiences, long-gone friends, foods, costumes, etc. Indeed, the multifarious nature of nostalgia’s objects was first systematically studied in 1995 by the American psychologist Krystine Batcho. She documented 648 participants’ nostalgic events, and found that, while they often reported feeling nostalgic about places, they also felt so about nonspatial items: loved ones, the feeling of ‘not having to worry’, holidays, or simply ‘the way people were’. Similarly, in 2006, the psychologist Tim Wildschut and his colleagues at the University of Southampton coded the content of 42 autobiographical narratives from Nostalgia magazine , as well as dozens of narratives from undergraduates, and found that a large proportion were about things other than locations. This variability holds across cultures too, as evidenced by the work of Erica Hepper and her international team who in 2014 studied 1,704 students from 18 countries and found that they frequently experienced nostalgia about things other than past events or places, including social relationships, memorabilia or childhood. These results suggest that mental states associated with nostalgia needn’t be memories of specific locations nor of specific autobiographical events.

Why, despite these results, do researchers insist that nostalgia is associated with a specific autobiographical memory? The reason, I believe, has more to do with experimental methodology than with psychological reality. Nostalgia researchers usually distinguish between ‘personal’ and ‘historical’ nostalgia; the former tends to be studied by social psychologists, while the latter tends to be studied in marketing. As a result, most experimental paradigms in the social psychology of nostalgia ask participants to think of specific memories that make them feel nostalgic. In contrast, marketing researchers tend to use historically dated external cues, such as ‘think of TV shows in the 1980s’, to elicit feelings of nostalgia – which are then associated with some sort of consumer behaviour (eg, TV ratings). Unsurprisingly, there is much psychological overlap between the two experimental strategies. Some marketing studies report that, when cued with products, participants can recall precise autobiographical memories, while other times they bring to mind less spatiotemporally precise events (eg, ‘my time in grade school’).

More interesting still is that nostalgia can bring to mind time-periods we didn’t directly experience. In the film Midnight in Paris (2011), Gil is overwhelmed by nostalgic thoughts about 1920s Paris – which he, a modern-day screenwriter, hasn’t experienced – yet his feelings are nothing short of nostalgic. Indeed, feeling nostalgic for a time one didn’t actually live through appears to be a common phenomenon if all the chatrooms, Facebook pages and websites dedicated to it are anything to go by. In fact, a new word has been coined to capture this precise variant of nostalgia – anemoia , defined by the Urban Dictionary and the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows as ‘nostalgia for a time you’ve never known’.

How can we make sense of the fact that people feel nostalgia not only for past experiences but also for generic time periods? My suggestion, inspired by recent evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience, is that the variety of nostalgia’s objects is explained by the fact that its cognitive component is not an autobiographical memory, but a mental simulation – an imagination, if you will – of which episodic recollections are a sub-class. To support this claim, I need first to discuss some developments in the science of memory and imagination.

Emotion researchers think of nostalgia as ‘bittersweet’ – as involving both positive and negative valences

Although memory and imagination are usually thought of as different, a number of critical findings in the past three decades have challenged this view. In 1985, the psychologist Endel Tulving in Toronto observed that his amnesic patient ‘N N’ not only had difficulty remembering his past: he also had trouble imagining possible future events. This led Tulving to suggest that remembering the past and imagining the future were two processes of a single system for mental time-travel. Further support for this hypothesis came in the early 2000s, as a number of scientific studies confirmed that both remembering the past and imagining the future engage the brain’s so-called ‘default network’. But in the past decade, it has become clear that the brain’s default network supports mental simulations of other hypothetical events too, such as episodes that could have occurred in one’s past but didn’t, atemporal routine activities (eg, brushing teeth), mind-wandering, spatial navigation, imagining other people’s thoughts (mentalising) and narrative comprehension, among others. As a result, researchers now think that what unifies this common neural network isn’t just mental time-travel, but rather a more general kind of psychological process characterised by being self-relevant, socially significant and episodically, dynamically imaginative. My suggestion is that the kinds of nonautobiographical cognitive contents associated with nostalgic states are instances of this broader category of imaginations.

If this suggestion is on the right track, then we can readily explain why people tend to feel nostalgia for possible objects other than specific past autobiographical events. The reason, I surmise, is because the cognitive contents associated with their nostalgic states are the kinds of mental simulations supported by the default network – which include, but are not limited to, autobiographical memories. Consequently, nostalgia can be associated with a possible past one didn’t experience, a concurrent nonactualised present, or even idealised pasts one couldn’t have lived but nevertheless can easily imagine by piecing together memorial information to form detailed episodic mental simulations (as in Midnight in Paris ). Finally, broadening up the cognitive contents of nostalgia from autobiographical memories to the larger class of dynamic episodic simulations just discussed also helps to explain why nostalgia is normally associated with facts and experiences that are personally meaningful and socially relevant.

Emotions have different valence: some are positive, some negative, and some both. Negatively valenced emotions include fear and sadness, while positively valanced emotions include happiness and joy. According to the traditional view, nostalgia is seen as a negative emotion: early medical reports described homesick patients as sad, melancholic and lethargic. The psychoanalytic tradition continued this view, and characterised nostalgia as involving sadness and pain. Indeed, it catalogued it as a particularly sad version of melancholia, tantamount to today’s depression.

Dissident voices suggested instead that there was something enjoyable about nostalgia. In 1872, for instance, Charles Darwin mentions that some feelings are difficult to analyse because they involve both pain and joy, and includes as an example Ulysses’ nostalgic recollection of his homeland. Almost 100 years later, and breaking with the psychoanalytic tradition, the American psychiatrist Jack Kleiner reported the case of a profoundly nostalgic patient that nonetheless exhibited joy, leading Kleiner to propose a difference between homesickness and nostalgia, on the grounds that the latter involves both sadness and joy. This distinction was later reformulated as depressive versus non-depressive nostalgia, with some even suggesting that the abnormal case of nostalgia is the depressive one, given that its pleasurable aspect is missing. Since then, emotion researchers have started to think of nostalgia as ‘bittersweet’ – as involving both positive and negative valences.

But what about all these negatively valenced symptoms – the sadness, the depression – associated with nostalgia? Aren’t they also effects of nostalgia? My sense is that physicians of old got the order of causation backwards: nostalgia doesn’t cause negative affect but, rather, is caused by negative affect. Evidence for this claim comes from a number of recent studies showing that people are more likely to feel nostalgia when they are experiencing negative affect. Specifically, it has been documented that certain negative experiences tend to trigger nostalgia, including loneliness, loss of social connections, sense of meaninglessness, boredom, even cold temperatures . This doesn’t mean that nostalgia is triggered only by negative experiences, but it does suggest that the negative affect can often be a cause, rather than an effect, of nostalgia.

The question now is, how can we make sense of nostalgia as involving both negative and positive valences at once? This becomes less surprising when we understand nostalgia as imagination. Often, when we entertain certain mental simulations, we go back and forth between the current act of simulating and the content that’s simulated. Both the act of simulating and the simulated content elicit emotions, and they needn’t be the same. Consider another paradigmatic dynamic mental simulation: upward counterfactual thoughts, or mental simulations about ways in which bad outcomes could have been better (‘If only I had arrived earlier, I would have got tickets for the show’). Typically, these kinds of counterfactual thoughts elicit feelings of regret.

However, as the American psychologists Keith Markman and Matthew McMullen demonstrated in 2003, if one mentally switches attention from the emotion felt while simulating the counterfactual to the emotion one feels when attending only to the simulated content, regret can turn into contentment. Conversely, one can imagine an alternative bad outcome to what in reality was a positive one (‘Had I missed that penalty kick, we would have lost the game’). Normally, these ‘downward counterfactuals’ elicit feelings of relief, a paradigmatically positive emotion. But when attention is focused only on the content of the counterfactual thought, not to the situation one’s in when simulating, negative emotions can ensue. Consequently, the discrepancy between the emotion felt when attending to the act of simulating versus the content of the simulation can account for the perceived ‘bittersweetness’ of nostalgia.

T he last component of the traditional view is the conative component, as nostalgia is thought to involve a desire to go back to one’s home. Despite its centrality, this component is seldom studied. To analyse it, philosophy can help once again. When thinking about desires, philosophers distinguish between the object and the conditions of satisfaction of a desire: the state of affairs that, were it to obtain, would fulfil the desire. Often, they are the same; if the object of my desire is a cookie, then getting a cookie fulfils my desire. But things get tricky with nostalgia. On the traditional view, the object of nostalgia is a location – say, one’s homeland – so the desire would be satisfied by going back. Since one cannot go back – think Ulysses – then the desire is unfulfilled, and negative affect ensues.

However, people often feel nostalgic for their homeland and, upon return, find their longing unsatisfied. Consider this essay’s epigraph. It describes García Márquez’s character Juvenal Urbino, a young doctor studying in Paris, as he reminisces about the odours, sounds and open terraces of his Caribbean homeland, wishing every second to go back. But, upon returning, he feels disappointed – tricked – by the rosy colours of an idealised nostalgic past. This difficulty is nostalgia’s incarnation of a well-known Platonic paradox described in the Gorgias : a person can desire something and then, when she gets it, the desire isn’t satisfied.

A possible solution is to think of the object of nostalgia’s desire as a place-in-time. This strategy allows for two possible readings. On one reading, what the individual desires is for her current self to travel back in time to where things were better than they currently are. This is painful because time-travel is impossible. On another reading, what the subject desires is for the past situation to be brought to the present; that is, she doesn’t wish to travel back in time to a past situation, but rather that the past situation could somehow replace the current one. Here, the object that could satisfy the nostalgic desire would be found not in the past but in the present, and what causes the pain is a different kind of impossibility: that of recreating the past in the present.

A more tractable version of this second reading was championed by Charles Zwingmann’s medical analysis of nostalgia in 1960, according to which what the subject wants is for gratifying features from past experiences to be reinstated in the present, presumably because the current situation lacks them. Although a person might feel nostalgia about a childhood friendship, her longing would actually be satisfied not by travelling back in time but by improving her current relationships. There are two advantages to this approach. First, it helps to understand nostalgia’s particular instantiation of Gorgias ’ paradox: the nostalgic individual wrongly attributes the desirable features of the object to an unrecoverable event, when in reality those features can be dissociated from it and reattached to a current condition. Second, this approach can help to understand recent findings suggesting that nostalgia can be motivational, and can increase optimism, creativity and pro-social behaviours.

Young people avidly support nostalgic policies that would return their nations to a past they never experienced

What drives this motivational spirit? Once again, the answer to this question comes from considering nostalgia as imagination. Neuroscience tells us that, when we imagine, we redeploy much of the same neural mechanisms that we would have employed had we actually engaged in the simulated action. When we imagine biking, we engage much of the same brain regions we’d have engaged had we actually been biking. As a result, some contemporary views – such as that of the psychologists Heather Kappes in London and Carey Morewedge in Boston – suggest that engaging in certain kinds of simulations is a way of economically substituting an experience for a cognitively close replacement – an ersatz experience, as it were.

Now recall my earlier discussion of the discrepancy in the valence felt when attention is directed to the simulated content versus the act of simulating. My proposal here is that what underlies the motivational aspect of nostalgia comes from a pleasurable reward signal that the subject momentarily experiences when attention is allocated to the simulated content. As it turns out, this is exactly what the neuroscientist Kentaro Oba and colleagues in Tokyo found in a 2016 study , where brain activity in regions associated with reward-seeking and motivation was higher during nostalgic recollection. Entertaining the kinds of mental simulations that elicit the bittersweet feeling of nostalgia generates a reward signal that seems to motivate individuals to turn their ersatz experience into a real one, in an attempt to replace the (actual) negative emotion felt when simulating with the (imagined) positive emotion of the simulated content.

Nostalgia, then, is a complex mental state with three components: a cognitive, an affective, and a conative component. This is generally recognised. However, my characterisation differs from the traditional one in putting imagination at its heart. First, I suggest that the cognitive component needn’t be a memory but a kind of imagination, of which episodic autobiographical memories are a case. Second, nostalgia is affectively mixed-valanced, which results from the juxtaposition of the affect generated by the act of simulating – which is typically negative – with the affect elicited by the simulated content, which is typically positive. Finally, the conative component isn’t a desire to go back to the past but, rather, a motivation to reinstate in the present the properties of the simulated content that, when attended to, make us feel good.

I will conclude with a brief speculation on a topic of contemporary importance. In the past few years, we’ve seen a resurgence of nationalistic political movements that have gained traction by way of promoting a return to the ‘good old days’: ‘Make America Great Again’ in the US, or ‘We Want Our Country Back’ in the UK. These politics of nostalgia promote the implementation of policies that, supposedly, would return nations to times in which people were better off. Unsurprisingly, such politics are usually heralded by conservative groups who, in the past, tended to be better off than they currently are – independently of the particular politics of the time. In a 2016 study conducted by the Polish social psychologists Monika Prusik and Maria Lewicka, a large sample of Poles were asked nostalgia-related questions about how things were prior to the fall of communism 25 years earlier. The results revealed that people felt much more nostalgic and had more positive feelings about the communist government if they were better off then than now, if they were older, and if they were currently unhappy. Doubtlessly, older and conservative-leaning folk who perceive their past – whether accurately or not – as better than their present account for a significant portion of the electorate supporting nationalistic movements. But we’d be misled to think of them as the primary engine, let alone the majority. For the Polish results show something very different: a large number of younger individuals avidly supporting nostalgic policies that would return their nations to a past they never experienced.

The psychological underpinnings of this phenomenon would be hard to explain under the traditional view of nostalgia. If people have not experienced a past, how can they feel nostalgic about it? However, under the view proposed here, an explanation is readily available. For the politics of nostalgia doesn’t capitalise on people’s memories of particular past events they might have experienced. Instead, it makes use of propaganda about the way things were, in order to provide people with the right episodic materials to conjure up imaginations of possible scenarios that most likely never happened. These very same propagandistic strategies help to convince people that their current situation is worse than it actually is, so that when the simulated content – which, when attended, brings about positive emotions – is juxtaposed to negatively valenced thoughts about their present status, a motivation to eliminate this emotional mismatch ensues, and with it an inclination to political action. The politics of nostalgia has less to do with memories about a rosy past, and more with propaganda and misinformation. This suggests, paradoxically, that the best way to counteract it might be to improve our knowledge of the past. Nostalgia can be a powerful political motivator, for better or for worse. Improving the accuracy of our memory for the past could indeed be the best strategy to curb the uncharitable deceptions of the politics of nostalgia.

A longer version of this article, titled ‘Nostalgia and Mental Simulation’, was published in The Moral Psychology of Sadness (2018), edited by Anna Gotlib.

Stories and literature

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

History of ideas

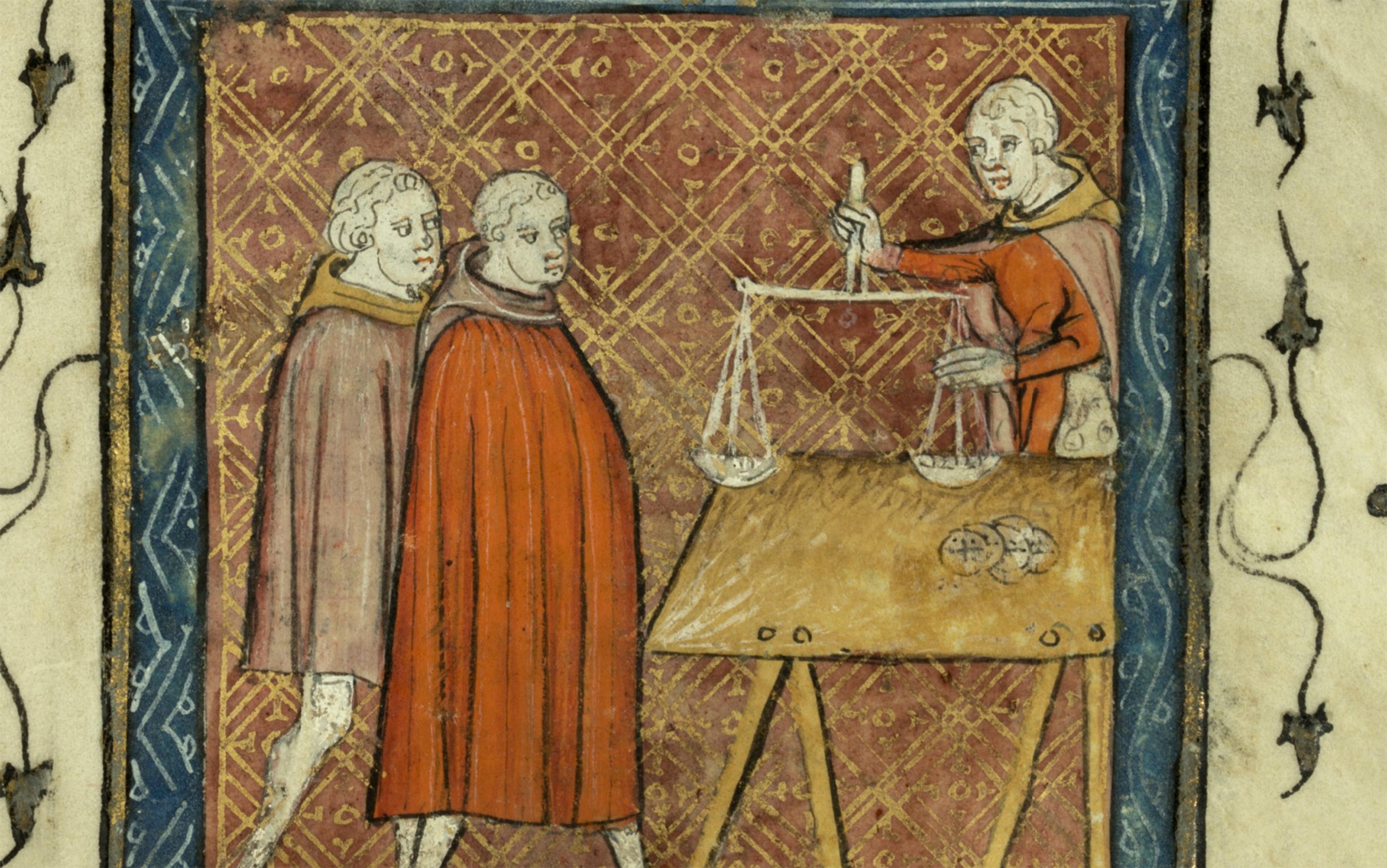

Reimagining balance

In the Middle Ages, a new sense of balance fundamentally altered our understanding of nature and society

What would Thucydides say?

In constantly reaching for past parallels to explain our peculiar times we miss the real lessons of the master historian

Mark Fisher

The environment

Emergency action

Could civil disobedience be morally obligatory in a society on a collision course with climate catastrophe?

Rupert Read

Metaphysics

The enchanted vision

Love is much more than a mere emotion or moral ideal. It imbues the world itself and we should learn to move with its power

Mark Vernon

What is ‘lived experience’?

The term is ubiquitous and double-edged. It is both a key source of authentic knowledge and a danger to true solidarity

Patrick J Casey

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

Why do we feel nostalgia?

- consciousness

- personality

- Literary Terms

- When & How to Write Nostalgia

- Definition & Examples

How to Write Nostalgia

- The best nostalgic writing is always based on real memories . It’s much easier to write as you get older and the world changes more and more around you, while your memories of the past get more and more solidified from playing them over and over in your head.

- The memories should be shared with your audience. Bring out details from the past that other people will remember as well. It works best if these memories are things that people haven’t thought about for a long time, so that their reaction is a sudden “Oh yeeeeeah!” moment.

- They should come from a specific time . Nostalgia shouldn’t just be about “the past,” but should be about a specific time period, for example “The 60s” or “When I Was in 3rd Grade.” Once you choose a specific time, dig into it for as many details as you can and pick out the ones that you think are especially unique and memorable.

- The memories need to be presented in a positive light , shorn of all negativity, discomfort, anxiety, etc. Nostalgia looks back on the past as a pure, perfect time of life.

When to Use Nostalgia

Nostalgia can be a great inspiration for short stories and poems. If there’s a time in your life that you remember fondly, put those memories on paper and shape them into a story or poem. In formal essays , there’s really not much point in using nostalgia. It may come up along the way, for example if you’re writing a paper about the Beatles and your reader looks back fondly on their memories of the 1960s. However, your purpose in an essay is to make an argument, not to evoke nostalgia. In fact, nostalgia can often be a bad thing in history papers, because it erases certain aspects of the truth — those that are negative or painful.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Psychology Emotional Intelligence

Definition, Perception and Concept of Nostalgia

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Erik Erikson

- Confirmation Bias

- Child Behavior

- Stanford Prison Experiment

- Stroop Effect

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

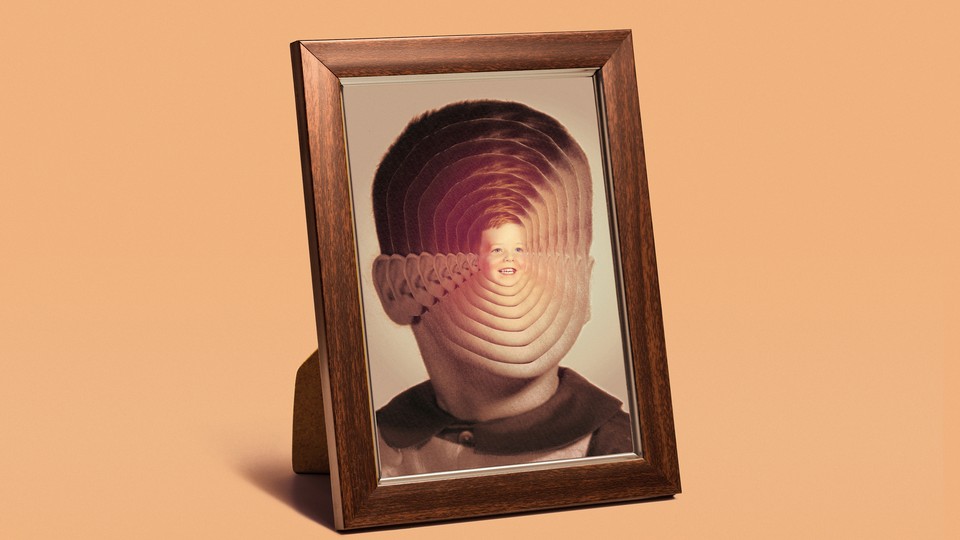

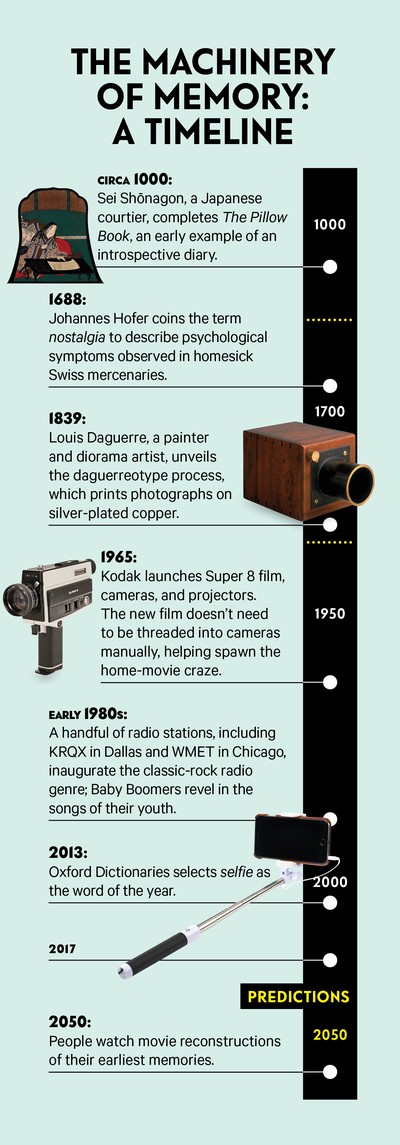

The End of Forgetting

Technology delivers nostalgia on demand.

When Uncle Joshua, a character in Peter De Vries’s 1959 novel, The Tents of Wickedness , says that nostalgia “ain’t what it used to be,” the line is played for humor: To those stuck in the past, nothing—not even memory itself—survives the test of time. And yet Uncle Joshua’s words have themselves aged pretty well (despite being widely misattributed to Yogi Berra): Technology, though ceaselessly striving toward the future, has continually revised how we view the past.

Explore the June 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Nostalgia—generally defined as a sentimental longing for bygone times—underwent a particularly significant metamorphosis in 1888, when Kodak released the first commercially successful camera for amateurs. Ads soon positioned it as a necessary instrument for preserving recollections of children and family celebrations. According to Nancy Martha West, the author of Kodak and the Lens of Nostalgia , the camera “allowed people … to arrange their lives in such a way that painful or unpleasant aspects were systematically erased.”

Technology is poised to once again revolutionize the way we recall the past. Not so long ago, nostalgia’s triggers were mostly spontaneous: catching your prom’s slow-dance song on the radio, riffling through photo albums while you were home for the holidays. Today, thanks to our devices, we can experience nostalgia on demand. The Nostalgia Machine website plays songs from your “favorite music year”; another app, Sundial, replays the songs you were listening to exactly a year ago. The Timehop app and Facebook’s On This Day feature shower you with photos and social-media updates from a given date in history. The Museum of Endangered Sounds website plays the noises of discontinued products (the chime of a Bell phone, the chirping of a Eurosignal pager). Retro Site Ninja lets you revisit web pages from the ’90s.

This is just the beginning: While these apps and websites let us glimpse the past, other technologies could place us more squarely inside it. But although psychologists believe nostalgia is crucial for finding meaning in life and for combatting loneliness, we don’t yet know whether too much of it will have negative, even dystopian, effects. As technology gives us unprecedented access to our memories, might we yearn for the good old days when we forgot things?

1 | Breaking the 3-D Wall

In her 1977 essay collection, On Photography , Susan Sontag wrote that photos “actively promote nostalgia … by slicing out [a] moment and freezing it.” Because a photograph’s perspective is fixed, a viewer can’t move within it, and is unable to experience the captured space the way the photographer or her subject did. New technology, however, can turn old photos into 3-D graphics that provide the illusion of moving through space.

Imagine the “ bullet time ” effect made famous by The Matrix —in which a scene’s action is either stopped or dramatically slowed down, while a camera seems to weave through the tableau at normal speed—applied to an old family photo, viewed on your laptop. Whereas The Matrix required 120 cameras to achieve its signature effect, a new approach known as 3-D camera mapping allows special-effects teams to inexpensively add dimensionality to 2-D photos. Recently, media designers like Miklós Falvay have used the approach to enhance archival images taken with a single still camera , giving viewers the impression that they are navigating spaces photographed years ago.

Artists have used other new techniques to project old photographs onto 3-D spaces. For its production of A 1940s Nutcracker , for example, the Neos Dance Theatre, in Mansfield, Ohio, used 3‑D‑graphics software to transform 1940s photos of Mansfield into virtual set pieces that dancers could interact with, creating the illusion that they were moving through old city streets. In this way, audience members who grew up in the ’40s were treated to the feeling of traveling through childhood landscapes.

Down the line, we may experience new forms of three-dimensional entertainment at home. Testing the appeal of holographic content, the BBC last year unveiled a rudimentary holographic TV , which used a variation on a Victorian theater technique—involving a transparent acrylic pyramid—to make footage of a beating heart and a dinosaur animation appear to float in midair. Although the BBC has no plans to bring such a TV to market, other companies are pursuing higher-tech commercial products, among them Samsung, which has patented a design for a TV that would broadcast laser-generated holographic images. When the technology is eventually perfected, people may watch home movies play out not on a screen but in the center of their living room.

2 | Reliving History

Even in 3-D, movies have a limited capacity for evoking real-life experiences. A viewer will never be able to choose his own perspective—to walk to another room, say, or to view a scene from the vantage point of a child rather than from that of a taller adult. Virtual-reality technology promises to give users a chance to do just that.

In a tantalizing example of how VR might be personalized in the future, Sarah Rothberg, an NYU researcher who specializes in virtual reality, has re-created her old house in “ Memory Place: My House ,” an Oculus Rift experience cum traveling art exhibit. Entering various rooms prompts the playing of home videos, filmed years before by Rothberg’s late father, whose early-onset Alzheimer’s disease inspired the project. After months of poring over old footage and photos, Rothberg was skeptical that the resulting experience would dislodge additional memories, but when she put on the Oculus Rift headset and walked across the virtual house’s parquet-floored hallway, something felt off: In the real house, a floorboard had been loose and rose at one end, though she had not thought about that fact in many years. As VR gear becomes cheaper, more of us might be able to re-create and then tour our own childhood homes—imagine an immersive, autobiographical version of Minecraft or The Sims.

3 | Backing Up Your Memories

Of course, to appreciate detailed replications of one’s past, one must have detailed memories of one’s past—and memory typically deteriorates with age. But experiments on other primates suggest that technological interventions may one day help us overcome this frailty. Theodore Berger, a biomedical engineer and neuroscientist at the University of Southern California, has developed a means of translating the neuron-firing pattern that the brain uses to code short-term memory into the pattern it uses to store long-term memory—a method he likens to translating “Spanish to French without being able to understand either language.” In some human trials, the translations have been found to be 90 percent accurate. Using this method, Berger’s team has created a mathematical model capable of recording the signals a rhesus monkey’s brain produces in response to stimuli, translating them, and feeding them back to the brain in order to facilitate long-term recall—even when the monkey has been drugged so as to inhibit the formation of lasting memories.

One day, we may even be able to create backups of our memories. In 2011, UC Berkeley researchers led by Jack Gallant, a cognitive neuroscientist, conducted an elaborate series of experiments that involved showing subjects video clips while taking fMRI scans of their brains, and then using a mathematical model to map how visual patterns translated into brain activity. After presenting a new clip to the subjects, the researchers used the resulting fMRI data to reverse engineer, from an archive of other footage, a video mashup that bore a striking resemblance to the clip the subjects had actually seen. Gallant believes that we could one day map brain activity triggered by a recalled memory and then reverse engineer a video of that memory.

For now, though, memory movies are a long way off. In a 2015 experiment, Gallant found that his model was three times more accurate at guessing the image a subject was looking at than at guessing one she was merely recalling. Another difficulty is that memories, especially nostalgic ones, shift over time. “What you recall is confabulated, made up,” Gallant told me. “Even if you can make a faithful reconstruction of a memory you decode from the brain, that memory is already wrong.”

Even if we had total recall, it might be best to avoid incessantly replaying memories, both for the sake of our psychological equilibrium and for the sake of our lives in the here and now. Ditto clicking from one nostalgia app to another. Clay Routledge, a psychology professor at North Dakota State University who wrote the leading textbook on nostalgia, says the emotion is typically healthy; in moderation, it can even lead you to seek out new experiences. But he cautions that “too much time focusing on the past could jeopardize your ability to engage in other opportunities that will form the basis for future nostalgic memories.” In other words, nostalgia really won’t be what it once was if, in the future, you have nothing to remember but the time you spent swiping through your phone, remembering.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

That yearning feeling: why we need nostalgia

Often misused by politicians, nostalgia is a positive emotion that could do with a makeover

I have always been prone to homesickness. As a child, I didn’t really enjoy holidays, I dreaded going away on school trips and I hated sleepovers. At the beginning of 2021, when I first started thinking about the history of nostalgia, and in the midst of the pandemic, I moved across the Atlantic from London to Montreal, Canada, for work. Far from home and away from my family and friends, I felt a kind of grief whenever I thought about the life I’d left behind. There was so much to love about my new life but I felt anxious, worrying constantly about the safety and wellbeing of my parents, siblings and friends. What if, due to the time difference, I missed an urgent call or woke up to terrible news? These fears were, of course, unfounded, and they were also ridiculous, childish even. Grownups – married 30-year-olds with mortgages and full-time jobs – shouldn’t miss their mums.

I also tend to be homesick in a weirder, more abstract way – homesick for somewhere I’ve never been. It’s a feeling otherwise known as nostalgia. Melding fairytales with Horrible Histories , as a child I spent hours imagining myself transported back in time to invented and romanticised versions of the past. I was an avid reader of Enid Blyton’s novels and, despite my homesick inclinations, begged my parents to divert me from my 1990s London primary school to a boarding school in 1950s Cornwall. My pleas went unanswered, so I went to my uniform-free state school every day in pleated skirts and white blouses, desperate to return to a world I’d never inhabited.

Growing up, I cut these emotional ties to the past, and history and I developed a new, much more cynical relationship. I did a few history degrees and became hardened to the past – a steely, objective academic who avoided sentimentality. Professional historians tend to have a low opinion of nostalgia and, at first, I absorbed this view. Nostalgia is, for many academics, a hallmark of history amateurs – more the preserve of re-enactors, hobbyists and popularisers. By contrast, we’re supposed to be able to focus a critical lens on the past, see it for what it is, warts and all.

In my personal life, I also became less nostalgic. I like to think of myself as politically progressive and I’m certainly an optimist. But despite holding these lofty ideas about myself, I still sometimes found myself languishing in the romanticism of the past, allowing myself a bit of nostalgia now and again, as a treat.

I’m slightly embarrassed of this because, even outside academia, nostalgia has a poor reputation. For many, it is a fundamentally (small-c) conservative emotion, one held by people unwilling to engage with modern life – the proverbial ostriches with their heads in the sand. It is, according to sociologist Yiannis Gabriel, “The latest opiate of the people.” At best, a mostly harmless condition experienced by antiquarians and sentimentalists. At worst, a kind of reactionary delusion, one blamed for a range of perceived social and political sins. But nostalgia used to be even worse. And you don’t need to travel that far back in time to find it listed as a cause of protracted illness, or even death. In the premodern world, it had the capacity to kill.

Nostalgia was first coined as a term and used as a diagnosis in 1688, by Swiss physician Johannes Hofer. Derived from the Greek nostos (homecoming) and algos (pain), this mysterious disease was a kind of pathological homesickness. It caused lethargy, depression and disturbed sleep. Sufferers also experienced physical symptoms – heart palpitations, open sores, and confusion. For some, the illness proved fatal – its victims refused food and slowly starved to death. In the 1830s, a Parisian man was threatened with eviction from his cherished home. He took to his bed, turned his face to the wall and refused to eat, drink or see his friends. Eventually he died, succumbing to a “profound sadness” and a “raging fever” just hours before his house was due to be demolished. His diagnosis? Nostalgia.

As the 20th century dawned, nostalgia loosened its grip on the medical mind, parted ways with homesickness and morphed into, first, a psychological disorder and, then, into the relatively benign emotion we know today. While they no longer considered nostalgia a physical sickness, early psychoanalysts still had little patience for the nostalgics they encountered on their couches. They accused people with nostalgic tendencies of being neurotic and unwilling or unable to face reality. Much like many political commentators today, they were snobbish, arguing that the middle classes were less likely to be nostalgic than “lower-class” or “tradition-bound” people.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that these views softened. Today, psychologists believe nostalgia is a near-universal, fundamentally positive emotion – a powerful psychological resource that provides people with a variety of benefits. It can boost self-esteem, increase meaning in life, foster a sense of social connectedness, encourage people to seek help and support for their problems, improve mental health and attenuate loneliness, boredom, stress or anxiety. Nostalgia is even now used as an intervention to maintain and improve memory among older adults, enrich psychological health and ameliorate depression.

Nostalgia is now supposed to be pleasurable for the individual experiencing it, but its reputation as an influence on politics and society is not so honeyed. Populist movements worldwide are repeatedly criticised for their use and abuse of nostalgia. The images these movements paint of the past are condemned for being overly white and overly male. It’s also seen as the preserve of those who are retrograde, conservative and sentimental. Writers lambast those who voted for Trump and Brexit for their nostalgic tendencies and it remains, strangely, a kind of diagnosis – an explanation for what the critic sees as wayward or irrational acts. As the historian Robert Saunders put it, in reference to Brexit, the prevailing rhetoric marked out the Leave vote as, “a psychological disorder: a pathology to be diagnosed, rather than argument with which to engage”.

This tendency is as widespread as it is strange. Not least because nostalgia is a feature of leftwing political life, just as it is of conservatism and populism – think of the NHS, for example. It is also strange because, if you take present-day psychology seriously, everyone is nostalgic, pretty much all the time.

Most experts agree nostalgia is a predominantly positive emotion that arises from personally salient, tender and wistful memories. And nostalgia is more than just benign; it can be actively therapeutic. As one psychologist put it, during moments of nostalgic reflection the mind is “peopled”. The emotion affirms symbolic ties with friends, lovers and families; the closest others come to being “momentarily part of one’s present”. People with nostalgic tendencies feel more loved and protected, have reduced anxiety, are more likely to have secure attachments and are even supposed to have better social skills.

Maybe I’d have felt less unhappy if I’d spent more of my time abroad indulging in nostalgia. Rather than wallowing in sadness and thinking of all the people I wasn’t with, I could have used those memories to remind me that I have friends and family to miss.At the very least, knowing more about the emotion and its history might have enabled me to disentangle my feelings from the assumptions I’ve held about what normal, appropriate emotional responses to change are supposed to look like.

The process of researching nostalgia shifted my intellectual relationship to emotions. Society as a whole, and especially academia, tends to see emotions as irritants. There is now a certain degree of cultural pressure to talk about feelings and to acknowledge trauma and distress publicly (a bit like I’m doing here) and seek help and support when unhappy, anxious, or depressed. But at the same time, some emotional responses are still seen as more appropriate or adult than others; and political and professional decisions seen to be driven by feelings are still taken less seriously than those deemed motivated by reason, rationality or research. As a historian, I’m keen on research. But as a historian of emotions, I’m also keen on feelings. I’m interested in their variety, curious about their range and I take their power seriously. Nostalgia could do with a makeover – it needs rescuing from its associations with the sick, the stupid and the sentimental.

Because the emotion is everywhere, a source of both pain and pleasure, and it explains so much about modern life. Expressions of nostalgia are one way we communicate a desire for the past, dissatisfaction about the present, and, perhaps paradoxically, our visions for the future. Progressive, as well as conservative; not just stultifying, it’s creative, too. Homesickness also needs to be treated with more respect. In its harmful, pathological forms, it must be taken more seriously. And even in its more benign manifestations, like mine, we should see it for what it is. Not as a contaminant, nor a thing that gets in the way of us living our lives, but as evidence for deep feeling – for connection and commitment. Proof that we love and are loved in return.

Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion by Agnes Arnold-Forster is published by Picador at £22. Buy a copy for £18.70 at guardianbookshop.com

- Life and style

- Self and wellbeing

- Health & wellbeing

Most viewed

Nostimon— Greek

- Examples: “ After many years traveling the world, I began to feel nostimon and knew it was time to return home, where I ultimately belonged.” [ancient]

- “My son came home from preschool today and told me he met a little girl he wants to marry when they’re old enough—it was so nostimon .” [modern]

Saudade— Portuguese and Galician

- Example: “ Despite the decades that have passed, I well up with an overpowering sense of saudade when I think back on the first summer I ever fell in love.”

Sehnsucht— German

- Example: “It seems silly, but something about this particular cast of light makes me long for the French Riviera circa 1923… It’s probably just sehnsucht. ”

Dor— Romanian

- Example: “ I used to come home every day to a snack my grandmother made me and I’d eat it watching after-school cartoons while she ironed—it was so cozy that thinking about it fills me with dor .”

Toska— Russian

- Example: “When it rains all afternoon I sometimes succumb to toska and spend hours staring out the window in a gloomy daze.”

Mono no aware— Japanese

- Example: “ When the seasons change so quickly and the weeks all start blending together, I remind myself of mono no aware and try to be more conscious of everyday beauty.”

Strange Nostalgia: An essay on music and memories

About once a year, sometime between May and August, I enter a self-imposed period of new music embargo. For two to four weeks, I put recent releases back on the shelf and dust off the relics of the past. Sometimes I listen to albums that shaped my listening habits when I was a teenager. Other times I unearth rare post-punk items from the ’80s, or wrap myself up in the comforting crackle of albums released before I was even born. And other times still, I’ll spin albums I forgot I even had.

I do this partly as a means of keeping from sickening myself on a diet of only fresh off the presses, or fresh out of my inbox, up-and-comers, the necessity of spending extra time with new releases sometimes contributing to an unwelcome case of fatigue. But I do this also as an act of sonic therapy. There’s something incredibly rewarding about getting re-acquainted with albums that have gone unnoticed for months or even years. And there’s something more rewarding still about listening to an album that holds such an important, sentimental place that you’ve memorized every note, but, nonetheless, you can’t wait to hear what’s around every turn.

In a way, our favorite albums are like old friends, and after a long period of having not heard them, the reunion seems ever more sweet. You get together and reminisce over a round of beers, telling the same old stories you’ve heard and relived time and time again. And you still laugh and smile, taking comfort in going over those details for the umpteenth time. Likewise, I can recite the bulk of The Dismemberment Plan’s Emergency and I , Jawbox’s For Your Own Special Sweetheart or Beulah’s When Your Heartstrings Break , but I take a certain comfort in tracing over those lines repeatedly, as if catching up with that old friend who now lives across the country.

Funny thing, then, that I’ve never considered myself a very nostalgic person, or so I thought. Back when old high school classmates had made an effort to track me down on MySpace, I felt strangely awkward and hesitant, and not all that interested in taking a trip back to my teenage years. I don’t keep up with old girlfriends. And while I look back fondly on old experiences, it’s an extremely rare circumstance that I would ever want to relive them. And yet, here I am, reveling in music that nourished me in the past, music that shaped my palette in its larval stage, ultimately coming to evolve into the insatiable, music devouring beast I am today.

So, despite how anti-nostalgic I might try to convince myself I am, I still find myself playing an album like 764-Hero’s Get Here and Stay , an album I bought when I was 17, and in many ways reminds me of that brief countdown to legal adulthood. Or perusing over my hand-written radio playlists from college, back when I hosted my own four-hour music marathon, every Wednesday evening. Or making iTunes playlists based on setlists of some of the best live shows I’ve ever seen (which, by the way, is a great idea just for the sake of making great single-artist mixes). And while there are numerous motives that might compel me to do so, the primary motivation behind these actions is, essentially, because they’re fun.

Music has a funny way of channeling emotions and memories in much the same way that a particular scent or taste can. And depending on your association with a particular song or album, it can be a source of great joy or pain. A friend of mine once said he couldn’t listen to A Certain Ratio’s “ Shack Up ” because of its negative associations with a person, an experience likely with which many readers will be familiar. Yet I can hear a song like Stone Temple Pilots’ “ Plush ,” a song that became popular during the brunt of my awkward, embarrassing years of puberty (years that I would prefer to forget, mind you), and somehow I’m brought back not to my horrible interactions with the opposite sex, but rather those days when my musical taste was still soft and malleable, ready to take the shape of anything with great enough impact.