The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, Vol. 30:1 Winter 2006

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Disability assessment

- Assessment for capacity to work

- Assessment of functional capability

- Browse content in Fitness for work

- Civil service, central government, and education establishments

- Construction industry

- Emergency Medical Services

- Fire and rescue service

- Healthcare workers

- Hyperbaric medicine

- Military - Other

- Military - Fitness for Work

- Military - Mental Health

- Oil and gas industry

- Police service

- Rail and Roads

- Remote medicine

- Telecommunications industry

- The disabled worker

- The older worker

- The young worker

- Travel medicine

- Women at work

- Browse content in Framework for practice

- Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and associated regulations

- Health information and reporting

- Ill health retirement

- Questionnaire Reviews

- Browse content in Occupational Medicine

- Blood borne viruses and other immune disorders

- Dermatological disorders

- Endocrine disorders

- Gastrointestinal and liver disorders

- Gynaecology

- Haematological disorders

- Mental health

- Neurological disorders

- Occupational cancers

- Opthalmology

- Renal and urological disorders

- Respiratory Disorders

- Rheumatological disorders

- Browse content in Rehabilitation

- Chronic disease

- Mental health rehabilitation

- Motivation for work

- Physical health rehabilitation

- Browse content in Workplace hazard and risk

- Biological/occupational infections

- Dusts and particles

- Occupational stress

- Post-traumatic stress

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Themed and Special Issues

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Books for Review

- Become a Reviewer

- About Occupational Medicine

- About the Society of Occupational Medicine

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Permissions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Hurricane Katrina: an American tragedy

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tee L. Guidotti, Hurricane Katrina: an American tragedy, Occupational Medicine , Volume 56, Issue 4, June 2006, Pages 222–224, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqj043

- Permissions Icon Permissions

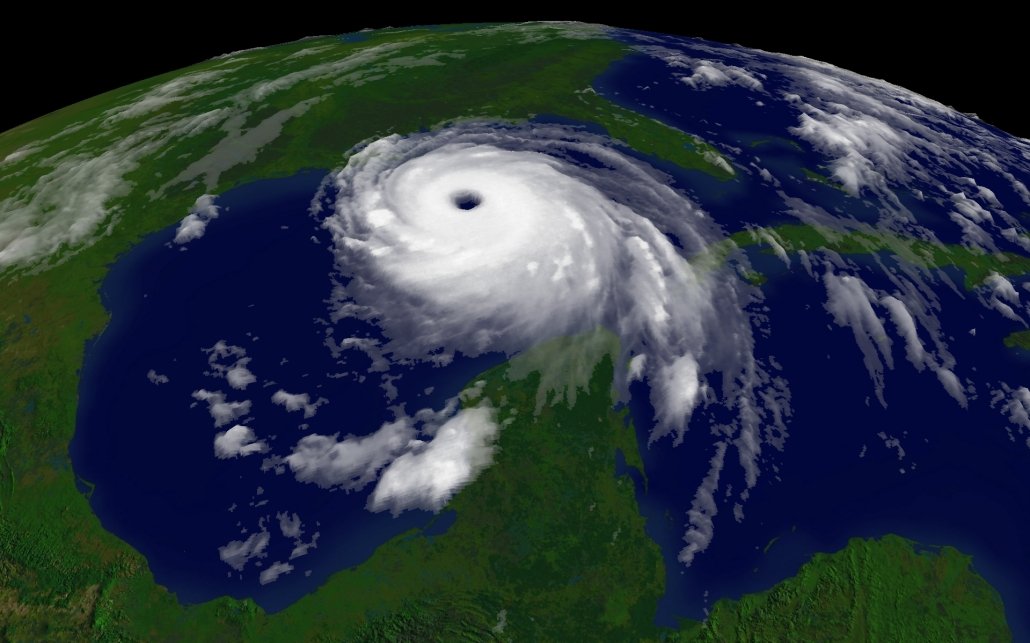

The true extent of the American tragedy that is Hurricane Katrina is still unfolding almost 12 months after the event and its implications may be far more reaching. Hurricane Katrina, which briefly became a Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, began as a storm in the western Atlantic. Katrina made landfall on Monday, 29 August 2005 at 6.30 p.m. in Florida as a Category 1 hurricane, turned north, gained strength and made landfall again at 7.10 a.m. in southeast Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane and rapidly attenuated over land to a Category 3 hurricane. New Orleans is below sea level as a consequence of subsidence and because of elevation of the Mississippi river due to altered flow. The storm brought a nearly 4 m storm surge east of the eye, where the winds blew south to the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain, and gusts of 344 km/h at the storm's peak at ∼1.00 p.m. Levees protecting the city from adjacent Lake Pontchartrain failed, inundating 80% of the city to a depth of up to 8 m. Further east in the Gulf Coast, a storm surge of 10.4 m was recorded at Bay St Louis, Mississippi [ 1 , 2 ].

What followed was horrifying and discouraging. Poor residents and the immobilized were left stranded in squalor. Essential services failed. Heroic rescues were undertaken with wholly inadequate follow-up and resettlement [ 3 ]. Emergency response was feeble. It was only after the military intervened that the situation began, slowly, to improve. New Orleans and much of the Gulf Coast to the east is still a depleted, devitalized, largely uninhabitable wreck. Less than a month later, on 24 September, Hurricane Rita followed. A much stronger storm in magnitude, Rita caused further displacement and disruption in Texas, where evacuation measures, undertaken in near-ideal conditions, were shown to be completely inadequate.

Floods usually conceal more than they reveal. Hurricane Katrina was an exception. It revealed truths about disaster response in the United States that had been concealed. Now, months later, one may assess the response and recovery to the disaster, evaluate how the country handled the challenge and determine what lessons were, or could have been, learned.

Katrina revealed that natural disasters and public health crises are as much threats to national security as intentional assaults. An entire region that played a vital role in the American economy and a unique role in the country's culture ground to a halt. During Katrina and Rita, ∼19% of the nation's oil refining capacity and 25% of its oil producing capacity became unavailable [ 4 ]. The country temporarily lost 13% of its natural gas capacity. Together, the storms destroyed 113 offshore oil and gas platforms. The Port of New Orleans, the major cargo transportation hub of the southeast, was closed to operations. Commodities were not shipped or accessible, including, in one of those statistics that are revealing beyond their triviality, 27% of the nation's coffee beans [ 5 ]. Consequences of this magnitude are beyond the reach of conventional terrorist acts.

Katrina revealed the close interconnection between the natural environment and human health risk. The capacity of wetlands in the Gulf Region to absorb precipitation and to buffer the effects of such storms has been massively degraded in recent years by local development. This has been known for a very long time [ 6 ], but development yielded short-term economic gain while mitigation was expensive. Katrina also revealed that understanding the threat and the circumstances that enable it means nothing if no concrete preparations are taken. The disaster that struck New Orleans, specifically, was not only foreseeable but also understood to be inevitable. Emergency managers had participated in a tabletop exercise that followed essentially an identical scenario just 13 months before, called ‘Hurricane Pam’ [ 7 ]. Had their conclusions and recommendations been acted upon, the actual event may have turned out differently. Although the levees would still have failed, perhaps those responsible for safeguarding the people would not have done so.

Katrina revealed that the federal agency designed to protect all Americans was incompetent. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reached its peak under President Clinton, when it enjoyed Cabinet-level rank. Post 9-11 FEMA was subordinated within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), a department highly focused on terrorism and intentional homeland threats. The wisdom of combining the two was always in doubt. The logical solution is to move FEMA out of DHS but so far there has been no political will to do so and FEMA is so reduced and depleted as an agency that it probably could not now operate at a Cabinet level even were it to have the authority [ 5 , 8 ].

Katrina revealed how large and resilient the American economy has become overall. The evidence for this is how quickly the country has returned to economic growth and business as usual, despite the destruction of a region once economically important [ 9 ]. Katrina devastated ≥223 000 km [ 2 ] of the United States, an area almost as large as Britain. Yet, with one exception, the economy of the country barely registered an effect, even on psychologically volatile indicators such as stock market indices. It is projected that Katrina, as such, will only reduce growth in GDP for the United States by about one half of 1%. Although the southeast region served by New Orleans is very large geographically, it constitutes only 1% of the total American economy [ 10 ]. The lower Mississippi region adds little of its own economic value to GDP, other than tourism and as a source of energy. The exception noted above, of course, was the price of oil, as reflected in the prices of gasoline and refined petroleum products.

Katrina revealed how marginal the Gulf Region had become to the American economy, despite the wealth that passes through it. New Orleans itself was a poor city—it probably still is, although the returning citizens obviously have sufficient resources to allow them to return—and its neighbours in Mississippi and Alabama are not rich, either. The region is economically significant mainly for tourism, transshipment of cargo, oil and gas and for redistribution of wealth (in the form of legalized gambling). Reconstruction efforts may even fuel an economic expansion in the rest of the economy, although precious little prosperity resulting from it is likely to be seen in the devastated Gulf itself anytime soon. Astonishingly, the compounded effect of the war in Iraq, the high price of crude oil and the direct effects of Hurricane Katrina did not set back growth in the American economy, although it may have kept stock market prices level to the end of 2005.

Katrina revealed the great divide that remains between people living next to one another but differing in the clustered characteristics of race, poverty, immobility and ill-health [ 11 , 12 ]. Those who lacked the resources, who could not fend for themselves, who were left behind, who happened to be sick were almost all African–American, and therefore so were the ones who died. Relatively, well off residents near the shore of Lake Pontchartrain also sustained many deaths [ 2 ]. However, the brunt of the storm was clearly borne by the poor and dispossessed. That this was not intentional does not make it any more acceptable.

Honour in this dishonourable story came from the role of rescue, medical, public health and occupational health professionals. Rescuers took personal risks to save the stranded citizens of New Orleans. Public health agencies quickly identified and documented the risks of water contamination [ 13 ], warned of risks from carbon monoxide from portable generators [ 14 ], identified dermatitis and wound infections as major health risks [ 15 ] and identified outbreaks of norovirus-induced gastroenteritis [ 16 ]. Occupational health clinics and occupational health physicians and nurses treated the injured, from wherever they came [ 17 ]. Occupational health professionals returned critical personnel to work as soon as it was possible, to hasten economic recovery and rebuilding. Occupational Safety and Health Administration professionals warned against hazards in the floodwaters and the destroyed, abandoned houses but supplies for personal protection were nowhere to be found. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Health served as a clearing-house for information and provided almost 200 participants with web-supported telephone training on Katrina-related hazards and measures to get workers back on the job safely.

It was not enough. No human effort could have been by then. But what can we, as a medical speciality, do better next time? The occupational health physician is not, as such, a specialist in emergency medicine, an expert in emergency management and incident command or a safety engineer, although many do have special expertise in these areas because of personal interest, prior training or military experience. The occupational health physician is, however, uniquely prepared to work with management and technical personnel at the plant, enterprise or corporate level. We can assist in preparing for plausible incidents, planning for an effective response, identifying resources that will be required, and advising on their deployment.

The occupational physician has critical roles to play in disaster preparedness and emergency management. Our role in disaster preparedness is distinct from those of safety engineering and risk managers. Our role in emergency management is distinct from those of emergency medicine and emergency management personnel. Our roles in both are complementary, sometimes overlapping and predicated on the value that we bring to the table as physicians familiar with facilities. We have the means to protect workers in harm's way and from the many hazards already so familiar from our daily work. Katrina demonstrates that occupational health professionals can translate experience of the ordinary to play an integral role in dealing with the extraordinary.

US National Interagency Coordinating Center. SITREP [Situation Report]: Combined Hurricanes Katrina & Rita. Access restricted but unclassified (3 January 2006 , date last accessed).

Wikipedia. Hurricane Katrina. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_Katrina (5 January 2006 , date last accessed).

Economist. When government fails, 2005 .

Bamberger RL, Kumins L. Oil and Gas: Supply Issues after Katrina. CRS Report for Congress RS222233. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2005 .

Time 2005 ; 166 : 34 –41.

Louisiana Wetlands Protection Panel. Towards a Strategic Plan: A Proposed Study. Chapter 5. Report of the Louisiana Wetlands Protection Panel. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Report No. 230-02-87-026, April 1987 . http://yosemite.epa.gov/oar/globalwarming.nsf/UniqueKeyLookup/SHSU5BURRY/$File/louisiana_5.pdf (6 January 2006, date last accessed).

Grunwald M, Glasser SB. Brown's turf wars sapped FEMA's strength. Washington Post 2005 ; 129 : A1 ,A8.

FEMA. Hurricane Pam exercise concludes. Region 4 Press Release R6-04-93. 24 July 2004 . http://www.fema.gov/news/newsrelease.fema?id=13051 (3 January 2005, date last accessed).

Samuelson RJ. Waiting for a soft landing. Washington Post 2006 ; 167 : A17 .

Fonda D. Billion-dollar blowout. Time 2005 ; 166 : 82 –83.

Atkins D, Moy EM. Left behind: the legacy of hurricane Katrina. Br Med J 2005 ; 331 : 916 –918.

Greenough PG, Kirsch TD. Hurricane Katrina: Public health response—assessing needs. N Engl J Med 2005 ; 353 : 1544 –1546.

Joint Taskforce. Environmental Health Needs and Habitability Assessment: Hurricane Katrina Response. Initial Assessment. Washington, DC and Atlanta, GA: US Environmental Protection Agency and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005 .

MMWR. Surveillance for Illness and Injury After Hurricane Katrina—New Orleans, Louisiana , 2005 .

MMWR. Infectious Disease and Dermatologic Conditions in Evacuees and Rescue Workers after Hurricane Katrina—Multiple States, August–September, 2005 , 2005 ; 54 : 1 –4.

MMWR. Norovirus among Evacuees from Hurricane Katrina—Houston, Texas , 2005 .

McIntosh E. Occupational medicine response to Hurricane Katrina crisis. WOEMA Quarterly Newsletter (Western Occupational and Environmental Medical Association) 2005 , pp. 2, 7.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact SOM

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-8405

- Print ISSN 0962-7480

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Occupational Medicine

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Remembering Katrina and Its Unlearned Lessons, 15 Years On

There’ve been so many storms — literal, cultural and political — since the hurricane hit New Orleans. But for the sake of all cities, we can’t forget it.

The author’s home in the Gentilly neighborhood of New Orleans in 2005, damaged by flooding from Hurricane Katrina. Credit... Sheryl Sutton Smith

Supported by

- Share full article

By Talmon Joseph Smith

Mr. Smith is a staff editor.

- Aug. 21, 2020

Listen to This Essay

To hear more audio stories from publishers like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android .

Early in the evening on Aug. 25, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Florida. A modest Category 1 storm, with top winds of only about 90 miles per hour, it passed just north of Miami, then lumbered across the Everglades toward the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

That night a birthday cake, white with pineapple filling, sat inside a glass cake stand on the dining room table at a house on the east corner of Dreux Street and St. Roch Avenue in New Orleans. It was my older brother’s birthday.

Within 72 hours, the storm grew into a colossal Category 5, its eye headed straight for the city. My family fled, leaving almost everything behind.

On Aug. 29, at 6:10 a.m., Hurricane Katrina slammed into the mouth of the Mississippi River as the fourth-most intense hurricane ever to make landfall in mainland America. Upriver in New Orleans, poorly made federal levees — which bracket the drainage canals coursing through the city — began to break like discolored Lego pieces when buffeted by storm surge. And a great deluge began.

On Aug. 31, President George W. Bush, who had been vacationing in Texas when the hurricane hit New Orleans , took a flyover tour of the destruction in Air Force One, while four-fifths of the city was underwater, and tens of thousands were stranded on rooftops, marooned on patches of dry streets or trapped in shelters.

On Sept. 2, as many still awaited rescue, and the death toll of more than 1,800 was still being tallied, The Baltimore Sun reported that the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Dennis Hastert, “questioned the wisdom of spending billions to rebuild a city several feet below sea level.” It was a common sentiment at the time — also published in mainstream outlets like Slate and The Washington Post — that New Orleanians have never forgotten.

A month or so later, my family returned to our home on Dreux Street, with masks and gloves, to survey the damage, a mildewed mess: our furniture, works by local artists, the old piano, all ruined. A chair hung from the chandelier. Below it on the counter, looking soggy yet almost untouched, was the birthday cake, still tucked inside its glass dome.

At the time, many here feared that “we may not see this city ever again, or at least not in the form we recognize,” as Wendell Pierce, the New Orleans native who starred in the HBO series “Tremé” about post-Katrina turmoil in the city, reminded me years later.

Mr. Pierce recalled how in those early months and years, “ Do You Know What It Means (to Miss New Orleans) ” by Louis Armstrong hit differently — not as bittersweet, but a dirge.

To his relief and that of millions of others, much of the city recovered after the hurricane, in its own uneven way.

Yet now, the coronavirus has killed over 4,000 Louisianans, put New Orleans’s service-based economy into a coma, shown the rest of America what a Katrina-size failure feels like and revealed how the lessons from the storm’s aftermath, regarding crisis management and social inequality, remain unlearned.

It can be hard to clearly remember August 2005 . There have been so many storms — literal, cultural and political — that have happened since. But we can’t forget the singularity of its disaster.

We can’t forget that the levees, properly built, easily “could have been sufficient” for the storm surge, as Stephen Nelson, a professor emeritus of earth and environmental science at Tulane University and author of the seminal paper “ Myths of Katrina: Field Notes From a Geoscientist ,” told me. But the Army Corps of Engineers failed to drive the steel pilings that hold levee panels together far enough into the earth , among other grave failures .

We can’t forget that, adjusted for inflation, the median Black household in the majority-Black city earned only about $30,000 in 2000, and that evacuating can cost thousands.

We can’t forget that despite commanding the greatest ground, air and naval forces in history, the U.S. government took roughly a week to put in place a thoroughly engaged rescue effort — leaving tens of thousands stuck without suitable shelter, food or water.

Precisely because the federal government was largely missing for days — while state and local officials were mired in petulant disarray — we can’t forget the heroic acts New Orleanians did for one another.

One of the first people I visited this month in New Orleans was Rudy Major, a man responsible for rescuing 125 or so people from floodwaters in my old neighborhood, Gentilly, according to his rough estimate. Mr. Major, a man full of jokes, is girded by a militarylike seriousness when ready to talk business.

He sat me down in his den and explained that he stayed as Hurricane Katrina approached because he was confident that his house, on a ridge, would not flood and because he was equally confident that the low-lying Ninth Ward, only a couple of miles away, would — and he wanted to help.

Soon after two nearby levees broke that Monday morning, Mr. Major hopped into his 30-foot boat with his son, Kyle, then 19. They made dozens of trips to fetch people in the surrounding area from their roofs and bring them back to his terrace, just safely above the waterline, “whether they looked white, Black, Creole, something else, whatever.”

They saw corpses float by. They hacked into an attic after hearing faint cries for help to discover a grieving woman with her two young daughters and their lifeless grandmother.

Such stories are just some of thousands of wrenching tales from the aftermath, created and compounded by government ineptitude. Mr. Major expressed a similar frustration with the government now, as the coronavirus strikes Louisiana with a particular severity.

“There are distinctions, but a lot of similarities,” he said. “You need a federal plan, a state plan, a local plan and they have to be connected.”

In 2005, the New Orleans mayor, Ray Nagin; Gov. Kathleen Blanco of Louisiana; Gov. Haley Barbour of Mississippi; and the Bush White House stumbled over logistics and wrestled over funding as lives were in the balance. In 2020, the cast of battling characters is simply broader, as governors from California to Texas to New York clash with mayors, and the Trump administration undermines them all, while refusing to take the lead itself.

Depending on where and who you are, the result of this politicized crisis response is just as deadly. “I’ve lost 15 friends to Covid,” Mr. Major said.

Pre-Katrina, there was already a considerable shortage of affordable housing in New Orleans . The situation has only become worse, as many of the affordable units the city had were never rebuilt after the storm and the urban core became whiter and wealthier.

New Orleans now has roughly 33,000 fewer affordable housing units than it needs, according to HousingNOLA , a local research and advocacy group. There are opportunities in every corner of the city to fix this, argued Andreanecia Morris, the executive director of HousingNOLA, when we met in her office in Mid-City on South Carrollton Avenue.

Most New Orleanians are renters. Pre-Katrina, the market rate for a one-bedroom apartment was around $578 monthly. It has roughly doubled since then, meaning a full-time worker must now earn about $18 per hour to afford a one-bedroom apartment.

Real wages, however, have stalled, and many of the places that employ New Orleanians remain closed. Tens of thousands of workers in the city’s beloved music, drinks, food and tourism businesses — who were the most likely to lose their livelihoods both after the storm and now during the pandemic — make a minimum wage of $7.25.

In some other cities, Ms. Morris explained, unaffordable rent “is the result of a housing stock shortage, but in New Orleans we have a vacancy rate of about 20 percent!” In total, there are about 37,700 vacant units. I could feel it biking and driving through the curvilinear streets that weave from the river to the lake, passing by elegant, unfilled properties on otherwise vibrant blocks, then by neatly rebuilt houses sitting lonely in areas frozen in 2007: three empty lots for every six homes you see.

Residents like Terence Blanchard, the Grammy Award-winning trumpeter, who resides in a thriving midcentury neighborhood along Bayou St. John, live this dichotomy. “People talk about the recovery,” he told me as we stood on his dock overlooking the water and City Park. “But if you go to my mom’s house in Pontchartrain Park, there was no real recovery.”

The federal housing vouchers mostly known by the shorthand “Section 8” — which subsidize rent payments above 30 percent of participants’ income — fully cover “fair market rate rent,” which in New Orleans is calculated as $1,034 to $1,496 for a one-bedroom apartment. That means even in increasingly upscale, higher-ground areas of town there is little stopping developers and landlords with vacant properties from lowering rents by a few hundred dollars and still being able to generate revenue.

For Ms. Morris, the continued holdout by many landlords that want “a certain kind of family,” or Airbnb customers, has grown to “psychotic” levels of classism and racism. “At a certain point,” she said, “the math has to let you at least manage your prejudices.”

I met Malik Bartholomew, a young local historian and born-and-raised New Orleanian , at the last Black bookstore in town, the Community Book Center, based in the Seventh Ward on Bayou Road. A cultural hub that was on the verge of closing because of the coronavirus, it’s been rescued for now by what the owner — known to her clientele as Miss Vera — views as a surge in white guilt after the death of George Floyd.

“Books started flying off the shelves,” Miss Vera said, her ambivalence visible despite the mask on her face.

Shortly after, Mr. Bartholomew gave me a history tour of the Faubourg Tremé, the iconic old neighborhood where I briefly worked as a teenager in 2013. Already gentrifying then, it’s become even fancier since.

As an eighth-generation New Orleanian, I wanted to be a good native and scoff at it all. But I found myself almost viscerally charmed by the carefully redone homes and the cafes frequented by young white people alongside the scene of a retired Black gentleman enjoying his shaded porch.

Couldn’t there be, I asked, a world in which some of the well-off people who come to visit and decide to stay then respect the culture, integrate into it, increase the tax base and help uplift others?

Mr. Bartholomew asserted — in between waving to residents he knew — that my integrationist daydream puts too much faith in “the Part 2,” in which wealth and power would be shared. “I’ve never seen that happen,” he said. “People just make money off our culture.”

As Mr. Bartholomew and other community organizers see it, “the wealthy interests are more powerful than ever.”

The mayor of New Orleans, LaToya Cantrell, said she largely agreed.

Ms. Cantrell, both the first woman and the first Black woman to lead the city , is from Broadmoor, one of the seven lower-lying neighborhoods that a panel appointed by the mayor’s office after Hurricane Katrina planned to transform into parks and wetlands.

She rose in local politics as a leading opponent of that failed plan and won the mayoralty on a platform of creating a New Orleans “for all New Orleanians.” But she confessed as we spoke in her sunlit yellow and blue City Hall office that, even before the coronavirus, every day felt like pushing a boulder uphill.

“All the time,” she told me, stretching out each syllable. “But if you don’t push, you’re not going to move. The systems that have been created, particularly in this city, are so that we’re doing all the pushing around here — and have been.”

Those systems are many and layered. There are regional business elites and the Federal Reserve — which has once again declined to be as generous to indebted municipalities as it’s been to the corporate markets it has saved. A hostile and controlling conservative state government blocks or vetoes many policies City Hall desires and starves the city of funds, even though much of the tax revenue generated in New Orleans goes to state coffers. As a result, Ms. Cantrell complained, she has no ability to make reforms like raising the minimum wage, and little room to redirect taxes or revenue.

So far, she has had more success with infrastructure projects, including a deal to divert some tax dollars from the tourism industry into initiatives that include a focus on sustainability. Instead of abandoning low-lying neighborhoods, the city is seeking to re-engineer their open spaces — like unused lots and wide avenues — into a network of water gardens, mini wetlands and drainage canals that feel more like babbling creeks. These “ blue and green corridors ” are meant to reduce flooding and reverse subsidence, the sinking of land, which has been increasing.

This reworked cityscape will be immensely beneficial to New Orleans’s viability if completed. But in the face of climate change — rising seas and disappearing wetlands to the south — Ms. Cantrell acknowledged it won’t be enough over the next 15 years.

There’s only so much, she said, that a mayor with a municipal budget can do — for wages, infrastructure, housing, education, economic mobility and more. And that’s true anywhere.

For all of New Orleans’s cultural uniqueness, for all of its ability to be a multicultural mecca in fleeting, festival moments, its struggles and needs are practically the same as every other urban area. Nearly everywhere, the city — this central, vital organ of modern society — is yet to be fairly figured out, with citizens living in just and environmentally stable harmony.

For such a city to be achieved, rich people of all colors will need to stop hoarding resources and live next to working people, schoolteachers may have to be paid like professors, living wages may need to be subsidized and epic adaptations will have to be made for climate change.

The scale of this need can be met only by the vast fiscal and monetary powers of the federal government. The alternative is for coastal areas around New Orleans, Miami, New York and Charleston, S.C., to become ever more unequal in the coming decades, sinking under the weight of their contradictions, then succumbing to nature and being overrun by the sea.

A day or so before I left town, I sat with Dr. Nelson, the Tulane geologist, in his backyard, and he told me he was skeptical of society’s ability to control coastal erosion in time. “For humans, if the return on investment isn’t immediate, you don’t do it,” he said. “But the Earth doesn’t work that way.”

For America to make an adequate pivot to environmentalism and egalitarianism may require a miracle unseen in lifetimes.

Still, as I took off from Louis Armstrong Airport, I noticed how within seconds we were soaring over the wetland created by the Mississippi River, much of it less than 1,000 years old, but now teeming with humans busying about, visible from a vehicle thousands of feet on high — a larger, more implausible-seeming miracle.

It reminded me of one of the last things Dr. Nelson told me, eyes smiling above his mask: “You can’t ignore what’s underneath you. Because you’re building everything on top of it.”

Talmon Joseph Smith is an economics reporter based in New York. More about Talmon Joseph Smith

Advertisement

- Afghanistan

- Budget Management

- Environment

- Global Diplomacy

- Health Care

- Homeland Security

- Immigration

- International Trade

- Judicial Nominations

- Middle East

- National Security

- Current News

- Press Briefings

- Proclamations

- Executive Orders

- Setting the Record Straight

- Ask the White House

- White House Interactive

- President's Cabinet

- USA Freedom Corps

- Faith-Based & Community Initiatives

- Office of Management and Budget

- National Security Council

- Nominations

Chapter Five: Lessons Learned

This government will learn the lessons of Hurricane Katrina. We are going to review every action and make necessary changes so that we are better prepared for any challenge of nature, or act of evil men, that could threaten our people.

-- President George W. Bush, September 15, 2005 1

The preceding chapters described the dynamics of the response to Hurricane Katrina. While there were numerous stories of great professionalism, courage, and compassion by Americans from all walks of life, our task here is to identify the critical challenges that undermined and prevented a more efficient and effective Federal response. In short, what were the key failures during the Federal response to Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina Critical Challenges

- National Preparedness

- Integrated Use of Military Capabilities

- Communications

- Logistics and Evacuations

- Search and Rescue

- Public Safety and Security

- Public Health and Medical Support

- Human Services

- Mass Care and Housing

- Public Communications

- Critical Infrastructure and Impact Assessment

- Environmental Hazards and Debris Removal

- Foreign Assistance

- Non-Governmental Aid

- Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned

- Homeland Security Professional Development and Education

- Citizen and Community Preparedness

We ask this question not to affix blame. Rather, we endeavor to find the answers in order to identify systemic gaps and improve our preparedness for the next disaster – natural or man-made. We must move promptly to understand precisely what went wrong and determine how we are going to fix it.

After reviewing and analyzing the response to Hurricane Katrina, we identified seventeen specific lessons the Federal government has learned. These lessons, which flow from the critical challenges we encountered, are depicted in the accompanying text box. Fourteen of these critical challenges were highlighted in the preceding Week of Crisis section and range from high-level policy and planning issues (e.g., the Integrated Use of Military Capabilities) to operational matters (e.g., Search and Rescue). 2 Three other challenges – Training, Exercises, and Lessons Learned; Homeland Security Professional Development and Education; and Citizen and Community Preparedness – are interconnected to the others but reflect measures and institutions that improve our preparedness more broadly. These three will be discussed in the Report’s last chapter, Transforming National Preparedness.

Some of these seventeen critical challenges affected all aspects of the Federal response. Others had an impact on a specific, discrete operational capability. Yet each, particularly when taken in aggregate, directly affected the overall efficiency and effectiveness of our efforts. This chapter summarizes the challenges that ultimately led to the lessons we have learned. Over one hundred recommendations for corrective action flow from these lessons and are outlined in detail in Appendix A of the Report.

Critical Challenge: National Preparedness

Our current system for homeland security does not provide the necessary framework to manage the challenges posed by 21st Century catastrophic threats. But to be clear, it is unrealistic to think that even the strongest framework can perfectly anticipate and overcome all challenges in a crisis. While we have built a response system that ably handles the demands of a typical hurricane season, wildfires, and other limited natural and man-made disasters, the system clearly has structural flaws for addressing catastrophic events. During the Federal response to Katrina 3 , four critical flaws in our national preparedness became evident: Our processes for unified management of the national response; command and control structures within the Federal government; knowledge of our preparedness plans; and regional planning and coordination. A discussion of each follows below.

Unified Management of the National Response

Effective incident management of catastrophic events requires coordination of a wide range of organizations and activities, public and private. Under the current response framework, the Federal government merely “coordinates” resources to meet the needs of local and State governments based upon their requests for assistance. Pursuant to the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and the National Response Plan (NRP), Federal and State agencies build their command and coordination structures to support the local command and coordination structures during an emergency. Yet this framework does not address the conditions of a catastrophic event with large scale competing needs, insufficient resources, and the absence of functioning local governments. These limitations proved to be major inhibitors to the effective marshalling of Federal, State, and local resources to respond to Katrina.

Soon after Katrina made landfall, State and local authorities understood the devastation was serious but, due to the destruction of infrastructure and response capabilities, lacked the ability to communicate with each other and coordinate a response. Federal officials struggled to perform responsibilities generally conducted by State and local authorities, such as the rescue of citizens stranded by the rising floodwaters, provision of law enforcement, and evacuation of the remaining population of New Orleans, all without the benefit of prior planning or a functioning State/local incident command structure to guide their efforts.

The Federal government cannot and should not be the Nation’s first responder. State and local governments are best positioned to address incidents in their jurisdictions and will always play a large role in disaster response. But Americans have the right to expect that the Federal government will effectively respond to a catastrophic incident. When local and State governments are overwhelmed or incapacitated by an event that has reached catastrophic proportions, only the Federal government has the resources and capabilities to respond. The Federal government must therefore plan, train, and equip to meet the requirements for responding to a catastrophic event.

Command and Control Within the Federal Government

In terms of the management of the Federal response, our architecture of command and control mechanisms as well as our existing structure of plans did not serve us well. Command centers in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and elsewhere in the Federal government had unclear, and often overlapping, roles and responsibilities that were exposed as flawed during this disaster. The Secretary of Homeland Security, is the President’s principal Federal official for domestic incident management, but he had difficulty coordinating the disparate activities of Federal departments and agencies. The Secretary lacked real-time, accurate situational awareness of both the facts from the disaster area as well as the on-going response activities of the Federal, State, and local players.

The National Response Plan’s Mission Assignment process proved to be far too bureaucratic to support the response to a catastrophe. Melvin Holden, Mayor-President of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, noted that, “requirements for paper work and form completions hindered immediate action and deployment of people and materials to assist in rescue and recovery efforts.” 4 Far too often, the process required numerous time consuming approval signatures and data processing steps prior to any action, delaying the response. As a result, many agencies took action under their own independent authorities while also responding to mission assignments from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), creating further process confusion and potential duplication of efforts.

This lack of coordination at the Federal headquarters-level reflected confusing organizational structures in the field. As noted in the Week of Crisis chapter, because the Principal Federal Official (PFO) has coordination authority but lacks statutory authority over the Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO), inefficiencies resulted when the second PFO was appointed. The first PFO appointed for Katrina did not have this problem because, as the Director of FEMA, he was able to directly oversee the FCOs because they fell under his supervisory authority. 5 Future plans should ensure that the PFO has the authority required to execute these responsibilities.

Moreover, DHS did not establish its NRP-specified disaster site multi-agency coordination center—the Joint Field Office (JFO)—until after the height of the crisis. 6 Further, without subordinate JFO structures to coordinate Federal response actions near the major incident sites, Federal response efforts in New Orleans were not initially well-coordinated. 7

Lastly, the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) did not function as envisioned in the NRP. First, since the ESFs do not easily integrate into the NIMS Incident Command System (ICS) structure, competing systems were implemented in the field – one based on the ESF structure and a second based on the ICS. Compounding the coordination problem, the agencies assigned ESF responsibilities did not respect the role of the PFO. As VADM Thad Allen stated, “The ESF structure currently prevents us from coordinating effectively because if agencies responsible for their respective ESFs do not like the instructions they are receiving from the PFO at the field level, they go to their headquarters in Washington to get decisions reversed. This is convoluted, inefficient, and inappropriate during emergency conditions. Time equals lives saved.”

Knowledge and Practice in the Plans

At the most fundamental level, part of the explanation for why the response to Katrina did not go as planned is that key decision-makers at all levels simply were not familiar with the plans. The NRP was relatively new to many at the Federal, State, and local levels before the events of Hurricane Katrina. 8 This lack of understanding of the “National” plan not surprisingly resulted in ineffective coordination of the Federal, State, and local response. Additionally, the NRP itself provides only the ‘base plan’ outlining the overall elements of a response: Federal departments and agencies were required to develop supporting operational plans and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to integrate their activities into the national response. 9 In almost all cases, the integrating SOPs were either non-existent or still under development when Hurricane Katrina hit. Consequently, some of the specific procedures and processes of the NRP were not properly implemented, and Federal partners had to operate without any prescribed guidelines or chains of command.

Furthermore, the JFO staff and other deployed Federal personnel often lacked a working knowledge of NIMS or even a basic understanding of ICS principles. As a result, valuable time and resources were diverted to provide on-the-job ICS training to Federal personnel assigned to the JFO. This inability to place trained personnel in the JFO had a detrimental effect on operations, as there were not enough qualified persons to staff all of the required positions. We must require all incident management personnel to have a working knowledge of NIMS and ICS principles.

Insufficient Regional Planning and Coordination

The final structural flaw in our current system for national preparedness is the weakness of our regional planning and coordination structures. Guidance to governments at all levels is essential to ensure adequate preparedness for major disasters across the Nation. To this end, the Interim National Preparedness Goal (NPG) and Target Capabilities List (TCL) can assist Federal, State, and local governments to: identify and define required capabilities and what levels of those capabilities are needed; establish priorities within a resource-constrained environment; clarify and understand roles and responsibilities in the national network of homeland security capabilities; and develop mutual aid agreements.

Since incorporating FEMA in March 2003, DHS has spread FEMA’s planning and coordination capabilities and responsibilities among DHS’s other offices and bureaus. DHS also did not maintain the personnel and resources of FEMA’s regional offices. 10 FEMA’s ten regional offices are responsible for assisting multiple States and planning for disasters, developing mitigation programs, and meeting their needs when major disasters occur. During Katrina, eight out of the ten FEMA Regional Directors were serving in an acting capacity and four of the six FEMA headquarters operational division directors were serving in an acting capacity. While qualified acting directors filled in, it placed extra burdens on a staff that was already stretched to meet the needs left by the vacancies.

Additionally, many FEMA programs that were operated out of the FEMA regions, such as the State and local liaison program and all grant programs, have moved to DHS headquarters in Washington. When programs operate out of regional offices, closer relationships are developed among all levels of government, providing for stronger relationships at all levels. By the same token, regional personnel must remember that they represent the interests of the Federal government and must be cautioned against losing objectivity or becoming mere advocates of State and local interests. However, these relationships are critical when a crisis situation develops, because individuals who have worked and trained together daily will work together more effectively during a crisis.

Lessons Learned:

The Federal government should work with its homeland security partners in revising existing plans, ensuring a functional operational structure - including within regions - and establishing a clear, accountable process for all National preparedness efforts. In doing so, the Federal government must:

- Ensure that Executive Branch agencies are organized, trained, and equipped to perform their response roles.

- Finalize and implement the National Preparedness Goal.

Critical Challenge: Integrated Use of Military Capabilities

The Federal response to Hurricane Katrina demonstrates that the Department of Defense (DOD) has the capability to play a critical role in the Nation’s response to catastrophic events. During the Katrina response, DOD – both National Guard and active duty forces – demonstrated that along with the Coast Guard it was one of the only Federal departments that possessed real operational capabilities to translate Presidential decisions into prompt, effective action on the ground. In addition to possessing operational personnel in large numbers that have been trained and equipped for their missions, DOD brought robust communications infrastructure, logistics, and planning capabilities. Since DOD, first and foremost, has its critical overseas mission, the solution to improving the Federal response to future catastrophes cannot simply be “let the Department of Defense do it.” Yet DOD capabilities must be better identified and integrated into the Nation’s response plans.

The Federal response to Hurricane Katrina highlighted various challenges in the use of military capabilities during domestic incidents. For instance, limitations under Federal law and DOD policy caused the active duty military to be dependent on requests for assistance. These limitations resulted in a slowed application of DOD resources during the initial response. Further, active duty military and National Guard operations were not coordinated and served two different bosses, one the President and the other the Governor.

Limitations to Department of Defense Response Authority

For Federal domestic disaster relief operations, DOD currently uses a “pull” system that provides support to civil authorities based upon specific requests from local, State, or Federal authorities. 11 This process can be slow and bureaucratic. Assigning active duty military forces or capabilities to support disaster relief efforts usually requires a request from FEMA 12 , an assessment by DOD on whether the request can be supported, approval by the Secretary of Defense or his designated representative, and a mission assignment for the military forces or capabilities to provide the requested support. From the time a request is initiated until the military force or capability is delivered to the disaster site requires a 21-step process. 13 While this overly bureaucratic approach has been adequate for most disasters, in a catastrophic event like Hurricane Katrina the delays inherent in this “pull” system of responding to requests resulted in critical needs not being met. 14 One could imagine a situation in which a catastrophic event is of such a magnitude that it would require an even greater role for the Department of Defense. For these reasons, we should both expedite the mission assignment request and the approval process, but also define the circumstances under which we will push resources to State and local governments absent a request.

Unity of Effort among Active Duty Forces and the National Guard

In the overall response to Hurricane Katrina, separate command structures for active duty military and the National Guard hindered their unity of effort. U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) commanded active duty forces, while each State government commanded its National Guard forces. For the first two days of Katrina response operations, USNORTHCOM did not have situational awareness of what forces the National Guard had on the ground. Joint Task Force Katrina (JTF-Katrina) simply could not operate at full efficiency when it lacked visibility of over half the military forces in the disaster area. 15 Neither the Louisiana National Guard nor JTF-Katrina had a good sense for where each other’s forces were located or what they were doing. For example, the JTF-Katrina Engineering Directorate had not been able to coordinate with National Guard forces in the New Orleans area. As a result, some units were not immediately assigned missions matched to on-the-ground requirements. Further, FEMA requested assistance from DOD without knowing what State National Guard forces had already deployed to fill the same needs. 16

Also, the Commanding General of JTF-Katrina and the Adjutant Generals (TAGs) of Louisiana and Mississippi had only a coordinating relationship, with no formal command relationship established. This resulted in confusion over roles and responsibilities between National Guard and Federal forces and highlights the need for a more unified command structure. 17

Structure and Resources of the National Guard

As demonstrated during the Hurricane Katrina response, the National Guard Bureau (NGB) is a significant joint force provider for homeland security missions. Throughout the response, the NGB provided continuous and integrated reporting of all National Guard assets deployed in both a Federal and non-Federal status to USNORTHCOM, Joint Forces Command, Pacific Command, and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Defense. This is an important step toward achieving unity of effort. However, NGB’s role in homeland security is not yet clearly defined. The Chief of the NGB has made a recommendation to the Secretary of Defense that NGB be chartered as a joint activity of the DOD. 18 Achieving these efforts will serve as the foundation for National Guard transformation and provide a total joint force capability for homeland security missions. 19

The Departments of Homeland Security and Defense should jointly plan for the Department of Defense’s support of Federal response activities as well as those extraordinary circumstances when it is appropriate for the Department of Defense to lead the Federal response. In addition, the Department of Defense should ensure the transformation of the National Guard is focused on increased integration with active duty forces for homeland security plans and activities.

Critical Challenge: Communications

Hurricane Katrina destroyed an unprecedented portion of the core communications infrastructure throughout the Gulf Coast region. As described earlier in the Report, the storm debilitated 911 emergency call centers, disrupting local emergency services. 20 Nearly three million customers lost telephone service. Broadcast communications, including 50 percent of area radio stations and 44 percent of area television stations, similarly were affected. 21 More than 50,000 utility poles were toppled in Mississippi alone, meaning that even if telephone call centers and electricity generation capabilities were functioning, the connections to the customers were broken. 22 Accordingly, the communications challenges across the Gulf Coast region in Hurricane Katrina’s wake were more a problem of basic operability 23 , than one of equipment or system interoperability . 24 The complete devastation of the communications infrastructure left emergency responders and citizens without a reliable network across which they could coordinate. 25

Although Federal, State, and local agencies had communications plans and assets in place, these plans and assets were neither sufficient nor adequately integrated to respond effectively to the disaster. 26 Many available communications assets were not utilized fully because there was no national, State-wide, or regional communications plan to incorporate them. For example, despite their contributions to the response effort, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service’s radio cache—the largest civilian cache of radios in the United States—had additional radios available that were not utilized. 27

Federal, State, and local governments have not yet completed a comprehensive strategy to improve operability and interoperability to meet the needs of emergency responders. 28 This inability to connect multiple communications plans and architectures clearly impeded coordination and communication at the Federal, State, and local levels. A comprehensive, national emergency communications strategy is needed to confront the challenges of incorporating existing equipment and practices into a constantly changing technological and cultural environment. 29

The Department of Homeland Security should review our current laws, policies, plans, and strategies relevant to communications. Upon the conclusion of this review, the Homeland Security Council, with support from the Office of Science and Technology Policy, should develop a National Emergency Communications Strategy that supports communications operability and interoperability.

Critical Challenge: Logistics and Evacuation

The scope of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation, the effects on critical infrastructure in the region, and the debilitation of State and local response capabilities combined to produce a massive requirement for Federal resources. The existing planning and operational structure for delivering critical resources and humanitarian aid clearly proved to be inadequate to the task. The highly bureaucratic supply processes of the Federal government were not sufficiently flexible and efficient, and failed to leverage the private sector and 21st Century advances in supply chain management.

Throughout the response, Federal resource managers had great difficulty determining what resources were needed, what resources were available, and where those resources were at any given point in time. Even when Federal resource managers had a clear understanding of what was needed, they often could not readily determine whether the Federal government had that asset, or what alternative sources might be able to provide it. As discussed in the Week of Crisis chapter, even when an agency came directly to FEMA with a list of available resources that would be useful during the response, there was no effective mechanism for efficiently integrating and deploying these resources. Nor was there an easy way to find out whether an alternative source, such as the private sector or a charity, might be able to better fill the need. Finally, FEMA’s lack of a real-time asset-tracking system – a necessity for successful 21st Century businesses – left Federal managers in the dark regarding the status of resources once they were shipped. 30

Our logistics system for the 21st Century should be a fully transparent, four-tiered system. First, we must encourage and ultimately require State and local governments to pre-contract for resources and commodities that will be critical for responding to all hazards. Second, if these arrangements fail, affected State governments should ask for additional resources from other States through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) process. Third, if such interstate mutual aid proves insufficient, the Federal government, having the benefit of full transparency, must be able to assist State and local governments to move commodities regionally. But in the end, FEMA must be able to supplement and, in catastrophic incidents, supplant State and local systems with a fully modern approach to commodity management.

The Department of Homeland Security, in coordination with State and local governments and the private sector, should develop a modern, flexible, and transparent logistics system. This system should be based on established contracts for stockpiling commodities at the local level for emergencies and the provision of goods and services during emergencies. The Federal government must develop the capacity to conduct large-scale logistical operations that supplement and, if necessary, replace State and local logistical systems by leveraging resources within both the public sector and the private sector.

With respect to evacuation—fundamentally a State and local responsibility—the Hurricane Katrina experience demonstrates that the Federal government must be prepared to fulfill the mission if State and local efforts fail. Unfortunately, a lack of prior planning combined with poor operational coordination generated a weak Federal performance in supporting the evacuation of those most vulnerable in New Orleans and throughout the Gulf Coast following Katrina’s landfall. The Federal effort lacked critical elements of prior planning, such as evacuation routes, communications, transportation assets, evacuee processing, and coordination with State, local, and non-governmental officials receiving and sheltering the evacuees. Because of poor situational awareness and communications throughout the evacuation operation, FEMA had difficulty providing buses through ESF-1, Transportation, (with the Department of Transportation as the coordinating agency). 31 FEMA also had difficulty delivering food, water, and other critical commodities to people waiting to be evacuated, most significantly at the Superdome. 32

The Department of Transportation, in coordination with other appropriate departments of the Executive Branch, must also be prepared to conduct mass evacuation operations when disasters overwhelm or incapacitate State and local governments.

Critical Challenge: Search and Rescue

After Hurricane Katrina made landfall, rising floodwaters stranded thousands in New Orleans on rooftops, requiring a massive civil search and rescue operation. The Coast Guard, FEMA Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) Task Forces 33 , and DOD forces 34 , in concert with State and local emergency responders from across the country, courageously combined to rescue tens of thousands of people. With extraordinary ingenuity and tenacity, Federal, State, and local emergency responders plucked people from rooftops while avoiding urban hazards not normally encountered during waterborne rescue. 35

Yet many of these courageous lifesavers were put at unnecessary risk by a structure that failed to support them effectively. The overall search and rescue effort demonstrated the need for greater coordination between US&R, the Coast Guard, and military responders who, because of their very different missions, train and operate in very different ways. For example, Urban Search and Rescue (US&R) teams had a particularly challenging situation since they are neither trained nor equipped to perform water rescue. Thus they could not immediately rescue people trapped by the flood waters. 36

Furthermore, lacking an integrated search and rescue incident command, the various agencies were unable to effectively coordinate their operations. 37 This meant that multiple rescue teams were sent to the same areas, while leaving others uncovered. 38 When successful rescues were made, there was no formal direction on where to take those rescued. 39 Too often rescuers had to leave victims at drop-off points and landing zones that had insufficient logistics, medical, and communications resources, such as atop the I-10 cloverleaf near the Superdome. 40

The Department of Homeland Security should lead an interagency review of current policies and procedures to ensure effective integration of all Federal search and rescue assets during disaster response.

Critical Challenge: Public Safety and Security

State and local governments have a fundamental responsibility to provide for the public safety and security of their residents. During disasters, the Federal government provides law enforcement assistance only when those resources are overwhelmed or depleted. 41 Almost immediately following Hurricane Katrina’s landfall, law and order began to deteriorate in New Orleans. The city’s overwhelmed police force–70 percent of which were themselves victims of the disaster—did not have the capacity to arrest every person witnessed committing a crime, and many more crimes were undoubtedly neither observed by police nor reported. The resulting lawlessness in New Orleans significantly impeded—and in some cases temporarily halted—relief efforts and delayed restoration of essential private sector services such as power, water, and telecommunications. 42

The Federal law enforcement response to Hurricane Katrina was a crucial enabler to the reconstitution of the New Orleans Police Department’s command structure as well as the larger criminal justice system. Joint leadership from the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security integrated the available Federal assets into the remaining local police structure and divided the Federal law enforcement agencies into corresponding New Orleans Police Department districts.

While the deployment of Federal law enforcement capability to New Orleans in a dangerous and chaotic environment significantly contributed to the restoration of law and order, pre-event collaborative planning between Federal, State, and local officials would have improved the response. Indeed, Federal, State, and local law enforcement officials performed admirably in spite of a system that should have better supported them. Local, State, and Federal law enforcement were ill-prepared and ill-positioned to respond efficiently and effectively to the crisis.

In the end, it was clear that Federal law enforcement support to State and local officials required greater coordination, unity of command, collaborative planning and training with State and local law enforcement, as well as detailed implementation guidance. For example, the Federal law enforcement response effort did not take advantage of all law enforcement assets embedded across Federal departments and agencies. Several departments promptly offered their assistance, but their law enforcement assets were incorporated only after weeks had passed, or not at all. 43

Coordination challenges arose even after Federal law enforcement personnel arrived in New Orleans. For example, several departments and agencies reported that the procedures for becoming deputized to enforce State law were cumbersome and inefficient. In Louisiana, a State Police attorney had to physically be present to swear in Federal agents. Many Federal law enforcement agencies also had to complete a cumbersome Federal deputization process. 44 New Orleans was then confronted with a rapid influx of law enforcement officers from a multitude of States and jurisdictions—each with their own policies and procedures, uniforms, and rules on the use of force—which created the need for a command structure to coordinate their efforts. 45

Hurricane Katrina also crippled the region’s criminal justice system. Problems such as a significant loss of accountability of many persons under law enforcement supervision 46 , closure of the court systems in the disaster 47 , and hasty evacuation of prisoners 48 were largely attributable to the absence of contingency plans at all levels of government.

The Department of Justice, in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security, should examine Federal responsibilities for support to State and local law enforcement and criminal justice systems during emergencies and then build operational plans, procedures, and policies to ensure an effective Federal law enforcement response.

Critical Challenge: Public Health and Medical Support

Hurricane Katrina created enormous public health and medical challenges, especially in Louisiana and Mississippi—States with public health infrastructures that ranked 49th and 50th in the Nation, respectively. 49 But it was the subsequent flooding of New Orleans that imposed catastrophic public health conditions on the people of southern Louisiana and forced an unprecedented mobilization of Federal public health and medical assets. Tens of thousands of people required medical care. Over 200,000 people with chronic medical conditions, displaced by the storm and isolated by the flooding, found themselves without access to their usual medications and sources of medical care. Several large hospitals were totally destroyed and many others were rendered inoperable. Nearly all smaller health care facilities were shut down. Although public health and medical support efforts restored the capabilities of many of these facilities, the region’s health care infrastructure sustained extraordinary damage. 50

Most local and State public health and medical assets were overwhelmed by these conditions, placing even greater responsibility on federally deployed personnel. Immediate challenges included the identification, triage and treatment of acutely sick and injured patients; the management of chronic medical conditions in large numbers of evacuees with special health care needs; the assessment, communication and mitigation of public health risk; and the provision of assistance to State and local health officials to quickly reestablish health care delivery systems and public health infrastructures. 51

Despite the success of Federal, State, and local personnel in meeting this enormous challenge, obstacles at all levels reduced the reach and efficiency of public health and medical support efforts. In addition, the coordination of Federal assets within and across agencies was poor. The cumbersome process for the authorization of reimbursement for medical and public health services provided by Federal agencies created substantial delays and frustration among health care providers, patients and the general public. 52 In some cases, significant delays slowed the arrival of Federal assets to critical locations. 53 In other cases, large numbers of Federal assets were deployed, only to be grossly underutilized. 54 Thousands of medical volunteers were sought by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and though they were informed that they would likely not be needed unless notified otherwise, many volunteers reported that they received no message to that effect. 55 These inefficiencies were the products of a fragmented command structure for medical response; inadequate evacuation of patients; weak State and local public health infrastructures 56 ; insufficient pre-storm risk communication to the public 57 ; and the absence of a uniform electronic health record system.

In coordination with the Department of Homeland Security and other homeland security partners, the Department of Health and Human Services should strengthen the Federal government’s capability to provide public health and medical support during a crisis. This will require the improvement of command and control of public health resources, the development of deliberate plans, an additional investment in deployable operational resources, and an acceleration of the initiative to foster the widespread use of interoperable electronic health records systems.

Critical Challenge: Human Services

Disasters—especially those of catastrophic proportions—produce many victims whose needs exceed the capacity of State and local resources. These victims who depend on the Federal government for assistance fit into one of two categories: (1) those who need Federal disaster-related assistance, and (2) those who need continuation of government assistance they were receiving before the disaster, plus additional disaster-related assistance. Hurricane Katrina produced many thousands of both categories of victims. 58

The Federal government maintains a wide array of human service programs to provide assistance to special-needs populations, including disaster victims. 59 Collectively, these programs provide a safety net to particularly vulnerable populations.

The Emergency Support Function 6 (ESF-6) Annex to the NRP assigns responsibility for the emergency delivery of human services to FEMA. While FEMA is the coordinator of ESF-6, it shares primary agency responsibility with the American Red Cross. 60 The Red Cross focuses on mass care (e.g. care for people in shelters), and FEMA continues the human services components for ESF-6 as the mass care effort transitions from the response to the recovery phase. 61 The human services provided under ESF-6 include: counseling; special-needs population support; immediate and short-term assistance for individuals, households, and groups dealing with the aftermath of a disaster; and expedited processing of applications for Federal benefits. 62 The NRP calls for “reducing duplication of effort and benefits, to the extent possible,” to include “streamlining assistance as appropriate.” 63

Prior to Katrina’s landfall along the Gulf Coast and during the subsequent several weeks, Federal preparation for distributing individual assistance proved frustrating and inadequate. Because the NRP did not mandate a single Federal point of contact for all assistance and required FEMA to merely coordinate assistance delivery, disaster victims confronted an enormously bureaucratic, inefficient, and frustrating process that failed to effectively meet their needs. The Federal government’s system for distribution of human services was not sufficiently responsive to the circumstances of a large number of victims—many of whom were particularly vulnerable—who were forced to navigate a series of complex processes to obtain critical services in a time of extreme duress. As mentioned in the preceding chapter, the Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) did not provide victims single-point access to apply for the wide array of Federal assistance programs.

The Department of Health and Human Services should coordinate with other departments of the Executive Branch, as well as State governments and non-governmental organizations, to develop a robust, comprehensive, and integrated system to deliver human services during disasters so that victims are able to receive Federal and State assistance in a simple and seamless manner. In particular, this system should be designed to provide victims a consumer oriented, simple, effective, and single encounter from which they can receive assistance.

Critical Challenge: Mass Care and Housing

Hurricane Katrina resulted in the largest national housing crisis since the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The impact of this massive displacement was felt throughout the country, with Gulf residents relocating to all fifty States and the District of Columbia. 64 Prior to the storm’s landfall, an exodus of people fled its projected path, creating an urgent need for suitable shelters. Those with the willingness and ability to evacuate generally found temporary shelter or housing. However, the thousands of people in New Orleans who were either unable to move due to health reasons or lack of transportation, or who simply did not choose to comply with the mandatory evacuation order, had significant difficulty finding suitable shelter after the hurricane had devastated the city. 65

Overall, Federal, State, and local plans were inadequate for a catastrophe that had been anticipated for years. Despite the vast shortcomings of the Superdome and other shelters, State and local officials had no choice but to direct thousands of individuals to such sites immediately after the hurricane struck. Furthermore, the Federal government’s capability to provide housing solutions to the displaced Gulf Coast population has proved to be far too slow, bureaucratic, and inefficient.

The Federal shortfall resulted from a lack of interagency coordination to relocate and house people. FEMA’s actions often were inconsistent with evacuees’ needs and preferences. Despite offers from the Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA), Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Agriculture (USDA) as well as the private sector to provide thousands of housing units nationwide, FEMA focused its housing efforts on cruise ships and trailers, which were expensive and perceived by some to be a means to force evacuees to return to New Orleans. 66 HUD, with extensive expertise and perspective on large-scale housing challenges and its nation-wide relationships with State public housing authorities, was not substantially engaged by FEMA in the housing process until late in the effort. 67 FEMA’s temporary and long-term housing efforts also suffered from the failure to pre-identify workable sites and available land and the inability to take advantage of housing units available with other Federal agencies.

Using established Federal core competencies and all available resources, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, in coordination with other departments of the Executive Branch with housing stock, should develop integrated plans and bolstered capabilities for the temporary and long-term housing of evacuees. The American Red Cross and the Department of Homeland Security should retain responsibility and improve the process of mass care and sheltering during disasters.

Critical Challenge: Public Communications

The Federal government’s dissemination of essential public information prior to Hurricane Katrina’s Gulf landfall is one of the positive lessons learned. The many professionals at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Hurricane Center worked with diligence and determination in disseminating weather reports and hurricane track predictions as described in the Pre-landfall chapter. This includes disseminating warnings and forecasts via NOAA Radio and the internet, which operates in conjunction with the Emergency Alert System (EAS). 68 We can be certain that their efforts saved lives.

However, more could have been done by officials at all levels of government. For example, the EAS—a mechanism for Federal, State and local officials to communicate disaster information and instructions—was not utilized by State and local officials in Louisiana, Mississippi or Alabama prior to Katrina’s landfall. 69

Further, without timely, accurate information or the ability to communicate, public affairs officers at all levels could not provide updates to the media and to the public. It took several weeks before public affairs structures, such as the Joint Information Centers, were adequately resourced and operating at full capacity. In the meantime, Federal, State, and local officials gave contradictory messages to the public, creating confusion and feeding the perception that government sources lacked credibility. On September 1, conflicting views of New Orleans emerged with positive statements by some Federal officials that contradicted a more desperate picture painted by reporters in the streets. 70 The media, operating 24/7, gathered and aired uncorroborated information which interfered with ongoing emergency response efforts. 71 The Federal public communications and public affairs response proved inadequate and ineffective.

The Department of Homeland Security should develop an integrated public communications plan to better inform, guide, and reassure the American public before, during, and after a catastrophe. The Department of Homeland Security should enable this plan with operational capabilities to deploy coordinated public affairs teams during a crisis.

Critical Challenge: Critical Infrastructure and Impact Assessment

Hurricane Katrina had a significant impact on many sectors of the region’s “critical infrastructure,” especially the energy sector. 72 The Hurricane temporarily caused the shutdown of most crude oil and natural gas production in the Gulf of Mexico as well as much of the refining capacity in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. “[M]ore than ten percent of the Nation’s imported crude oil enters through the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port” 73 adding to the impact on the energy sector. Additionally, eleven petroleum refineries, or one-sixth of the Nation’s refining capacity, were shut down. 74 Across the region more than 2.5 million customers suffered power outages across Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. 75