Advertisement

Supported by

Turning Points: Guest Essay

The Big Question: Is the World of Work Forever Changed?

We asked a group of professionals from around the world to envision what working will look like in 2022 and beyond.

- Share full article

By The New York Times

This article is part of a series called Turning Points , in which writers explore what critical moments from this year might mean for the year ahead. You can read more by visiting the Turning Points series page .

During the life-changing Covid-19 pandemic, millions of people were fortunate enough to work from home during lockdowns, while others were called upon to put themselves at physical risk to keep cities and economies from collapsing. As the world re-emerges from Covid, we are seeing renewed attention in the workplace to issues of social injustice, economic inequality, corporate social responsibility, and diversity and inclusion.

Earlier this year, we asked a small group of leaders in various professions: Is the world of work forever changed?

Their answers have been edited and condensed.

Vicky Lau: ‘People Are Looking for True Fulfillment’

Over the past two years, the food and beverage industry has evolved rapidly. Restaurants and bars have scrambled to adapt to and survive the unprecedented rules and regulations brought on by the pandemic that have ultimately led to the demise of thousands of establishments around the world. Meanwhile, Covid-19 lockdowns and new technologies have pushed workers to switch jobs or pursue entirely new careers.

There has been a noticeable shift away from the traditional career restaurant worker to one preferring to juggle multiple jobs or jump from one to the next. People are looking for true fulfillment in their lives and careers, and with e-commerce businesses easier to set up than ever, workers have become their own bosses and have even started their own enterprises. Restrictions on indoor dining, coupled with the fact that many people are working from home, have created a new pattern of habits with regard to how food is both approached (rediscovering a love for home cooking) and consumed (the mushrooming use of food delivery apps).

In Hong Kong, consumers have adopted much healthier eating habits. A new global focus on self-care means many people want to be the best version of themselves coming out of the pandemic. More business owners are also sourcing locally, connecting with regional farmers and experimenting with their own creations.

Aligning with shifting consumer needs while taking on waves of lockdown restrictions are just two of the many ways in which the industry has struggled to stay on top of the game.

In the future, our relationship with food will have to go back to the very beginning: good ingredients. For chefs, whether we’re preparing a traditional meal or adapting to a new way of dining, sourcing will be critical. The future of the industry depends on it.

Vicky Lau is the executive chef and owner of Tate Dining Room in Hong Kong.

Billy Bragg: ‘The Validation of the Crowd’

I’ve always been an itinerant worker. Some musicians earn enough money from their recordings, but most of us make our living out on the road. Since I turned professional 35 years ago, I’ve plied my trade all over the world. When the pandemic hit in 2020, I had dates booked in Australia, New Zealand, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States. As clubs and theaters went dark and my tours were postponed, I felt certain that this thing would all be over in time for the summer festivals. Then the cancellation of the annual Glastonbury Festival in Somerset, England, brought home the seriousness of the situation.

When the first lockdown in Britain was announced, like many musicians I was confronted by the steep learning curve facing any performer who chooses to work live on the internet. As a young man I’d enjoyed watching myself in the bedroom mirror, striking rock star poses while strumming furiously on a tennis racket. These days, playing an hour of songs with nothing to look at but my own reflection staring back at me from a smartphone screen hasn’t been quite so engaging, and the only discernible crowd reaction has been the stream of emojis bubbling up silently as I play.

Yet it’s not only performers who need the validation of the crowd. Music has a way of making us feel that we are not alone and gives us a sense that others also face the emotional quandaries we do. That feeling of empathy is never more powerful than when it’s experienced at a live concert.

To have a song that has fortified your resolve to rise above your problems, and then find yourself in the presence of the artist who provided that impetus, can be an energizing experience. When they sing your song, and hundreds — maybe thousands — of other voices join with yours in response, the sense of validation is euphoric. This is a moment of blessed communion, during which doubt and disconsolation are swept away. You leave the venue with your resilience recharged.

While the pandemic may transform the way we see the world and lead to long-lasting changes in the way some people work, I’m convinced that in my line of business, things will remain much as they ever were. The emotional solidarity of the live event is not something that can easily be replicated online.

Billy Bragg is a British singer, songwriter, activist and social commentator.

Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers: ‘A More Humane Labor Market’

Before the pandemic, most of us tried to maintain a boundary between our work lives and our lives at home. Children were seen rarely, and then mostly in desktop photos. Parents quietly adjusted their schedules without drawing attention to their caregiving obligations.

The pandemic shredded these porous boundaries. Suddenly, kids were in full view on Zoom; a barking dog or dancing cat might provide a moment of levity. Employers adjusted to scheduling around our caregiving responsibilities.

Pulling back this curtain on our personal lives has transformed our relationship with work. The results are reflected in both our actions and our intentions. Job resignations hit an all-time high in 2021, and workers are changing industries and occupations more frequently than they did before the pandemic. Surveys show that more than half of U.S. workers have an eye toward new employment. Only a quarter of U.S. fathers and a third of mothers surveyed said that they plan to keep on working as they did before the pandemic — the rest aspire to change the number of hours they work, or look for a different type of job.

Necessity has forced change, and led each of us to reimagine what’s possible. And that reimagining has led workers to see more control for themselves, and better opportunities ahead.

For some this will mean not returning to the office full time. The typical worker whose job can be done there is likely to continue working from home at least part of the time. The time saved (in billions of collective hours) and convenience (say, throwing in a load of laundry between meetings) generated benefits too great to give back.

Beyond working from home, many people are looking for something new. They are negotiating where and how much they choose to work, and are walking away from low-paying, high-risk jobs. Some want to strike a better balance by working less or finding a less stressful or demanding position. Others are seeking better opportunities to build the career they truly want. The shifting pandemic economy, in which there are a record number of job openings , has given workers the bargaining power to demand — rather than merely hope for — these changes.

Every economic upheaval needs a name. Call this one The Great Reallocation. It might be disruptive for a little while, but the result just might be a more humane labor market.

Betsey Stevenson, an American economist, and Justin Wolfers, an Australian economist, are professors of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan. They are experts on the economics of marriage, divorce and child-rearing.

Tina Brown: ‘People Felt Profound Digital Burnout Long Before Covid’

The more the virus refuses to go gently into the night, the clearer it becomes that a post-Covid world is simply an illusion.

The workplace is less a place than an elusive, shape-shifting locus of professional self-doubt; even more of a mirage for bosses than it is for employees. The boss may think she has a staff, but what she’s got are ghost soldiers — push them a little and they melt away. This leaves managers powerless in the face of demands for a hybrid office, a creature which only works if employees come in to work simultaneously. If they don’t, it’s impossible to hold a meeting without critical gaps at the table. It means having a sprinkling of nominal participants who log in and are forgotten about, and a no-show or two who later explain, “I’m sorry I missed that one — the Wi-Fi in Vermont is really bad.”

And let’s not forget Facebook’s virtual reality technology , in which absent co-workers appear as avatars, forcing the others to wear clunky headsets just to see the assistant marketing director as (perhaps fittingly) a nodding cartoon.

One misbegotten takeaway from the “new workplace” discussion is that many employees prefer to stay at home because they are more productive. Uh, no. People felt profound digital burnout long before Covid. If there is one common denominator in the elusive post-Covid mood, it’s that most sane people don’t want to work much at all. They prefer to do just enough to keep the wolf from the door and uphold a dash of professional relevance.

Old-school human resources departments are a thing of the past. Ghost soldiers don’t want to share their work problems with a suit whose role is to pacify you on behalf of government. Work and personal life have been irretrievably blurred in the Zoom world. I predict a growing use of pastoral care agencies like Sarah McCaffrey’s Solas Mind , which provides mental health support to freelancers in the creative sector.

Lockdown life revealed how fragile we all are — and how much we want to talk about it. The answer to office work in the future is clear: Employees should commute to the office for the same three-day week, then melt away to their newly treasured secret worlds.

Tina Brown is a journalist and author and the former editor of Vanity Fair and The New Yorker magazines.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter: ‘Tech Enables, but Humans Make the Rules’

Covid disruption could be the turning point for adopting — finally — quality work-life practices proposed for decades. Flexible schedules, equal opportunity for women and minorities, a good balance between work and family, and socially responsible companies have long been on the horizon as distant hopes.

One driver is technology. Tech contributes to change by enabling work from anywhere. It transforms institutions and makes services more accessible, whether education online or health care through telemedicine, robotic surgery or home health monitoring. Labor shortages in poorly paid rote jobs make room for robots, such as the robotic restaurant in my tech-heavy neighborhood. Goodbye, wage slavery.

But tech won’t create a workers’ paradise without bigger reforms. In-person face time is still an advantage for workers who can get to a workplace, which means that they need accessible child care and transportation, which have yet to materialize on a large scale. And a tech-dominated world carries troubling possibilities for control through increasingly sophisticated surveillance techniques, unless worker autonomy is protected.

Another potent driver of change is worker activism, led by younger top talent. Emboldened by competition for their skills and fueled by a mistrust of establishments, they protest undesirable customers, environmentally unfriendly products, rigid work requirements, discriminatory treatment and serial harassers. They seek greater participation in decisions, self-organizing to act directly rather than waiting for permission. They reinforce external pressure groups in holding businesses to ever-higher standards, and thus help corporate social responsibility programs and environmental, social and governance reporting become mainstream expectations.

That’s not enough. Unless workplaces better help workers realize their family priorities and personal values, jobs will cease being a central source of identity. The Great Resignation could continue, especially if entrepreneurship becomes a viable path for women and racial minorities — when they can break through the white male hold on venture capital. Without workplace transformation, paid work will be purely transactional, a loyalty-less survival necessity with loose ties akin to gig work. Even for the well-paid, jobs will be a sidetrack, dispensed with quickly so that the real business of living can begin. The charity road race will replace the rat race. The best work situations will offer opportunities for community service.

Work won’t morph from wage slavery into a workers’ paradise without a culture and public policies that require accessible child care, flexible schedules, a voice in decisions and social responsibility. Tech enables, but humans make the rules.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter is a professor of business at Harvard Business School who specializes in change leadership and innovation. Her latest book is “Think Outside the Building: How Advanced Leaders Can Change the World One Smart Innovation at a Time.”

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Future of Work, Essay Example

Pages: 5

Words: 1450

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The Future of Work

People spend a third of their adult lives working, which has led to many of them looking for ways to reimagine work. Since people have to work to guarantee their survival and wealth, methods of making work more flexible and comfortable are being developed, a phenomenon regarded as the future of work. The future of work will involve working in places with equity and inclusion. Many businesses are changing to accommodate a stress-free working environment. Company leaders are starting to establish a culture of trust in their organizations, which will allow them to become more transparent, compassionate, and acquiring more vulnerable management styles. This essay discusses the characteristics that will define a flexible and comfortable workplace and how workers are being prepared to adapt to the future of work.

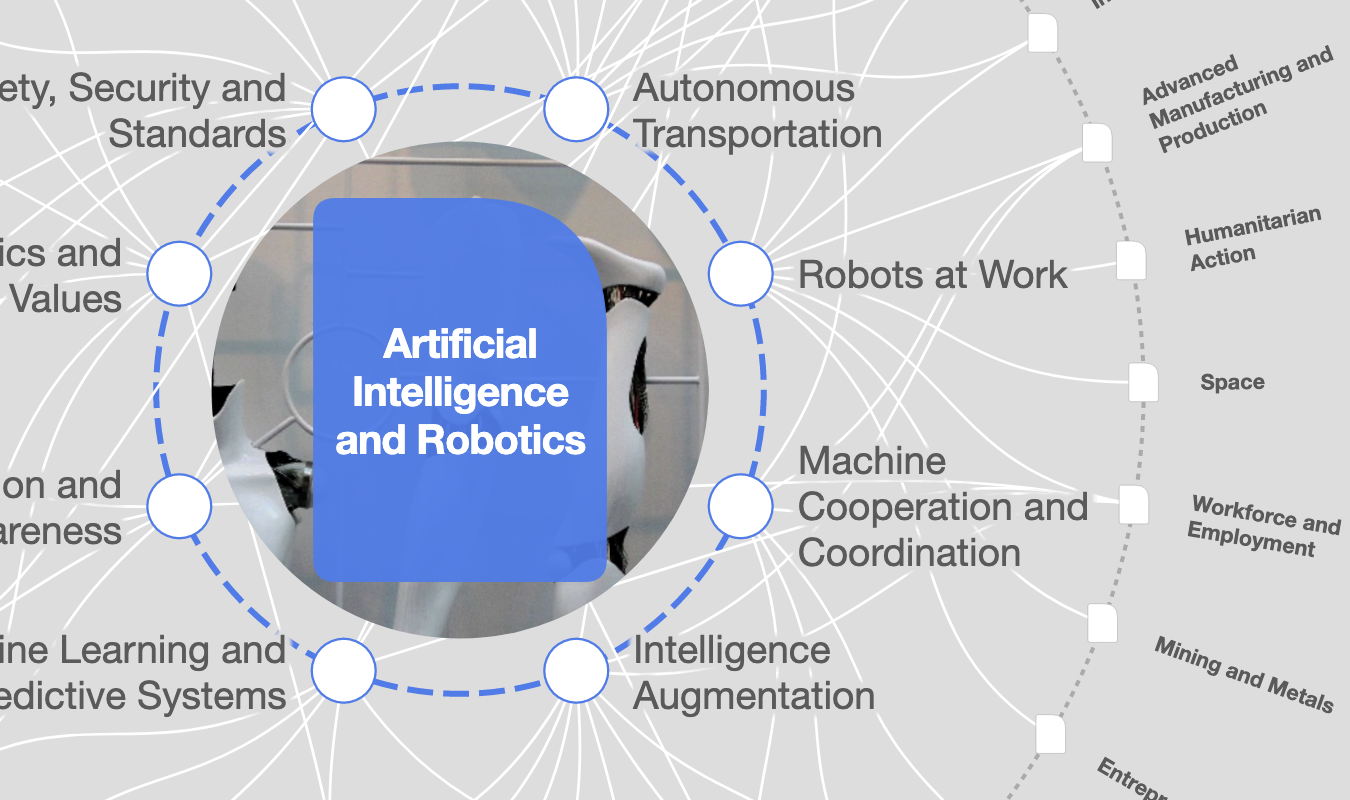

Artificial Intelligence

Many fields of work, such as health and development of leadership are continuously growing, which has led to the experts in these fields to seek wellness and professional advice from technical experts to help in their work. Artificial Intelligence has replaced many jobs, as Massachusetts Institute of Technology predicted a decade ago, that by 2017, the 1.7 million trucking jobs will be replaced by Artificial Intelligence Systems (Wang 10).

Seeking Flexibility and Autonomous work

Self-employment, which started in the UK after there was a global crisis, was regarded as an alternative that people took because there was no employment. However, when jobs became available, and there was an improvement in the economy, self-employment rates also went up. People involuntarily became self-employed, because they wanted to work flexible, and any age and a pace where they did not require to be controlled. This is similar to the use of new digital platforms in the workplace. Many employers are seeking to improve their workplace by allowing people to work the way they want to work through the use of digital technology. However, this will also affect a certain amount of employees who will need to be terminated to give room for the digital platforms.

Distribution

In the 20 th and early 21 st century, most jobs involved people being in a physical location. However, in the modern world, there are tools and new approaches that have allowed work to be successfully executed with people distributed across many places, including continents apart. For instance, the company Automattic has 762 people from 68 countries, and they speak 81 different languages (Franck 442). The employees meet online because of the availability of transparency, which allows them to understand each other. Based on the development of teleworking and open-source software projects that have made distribution easier, many companies are seeking to do away with offices, allowing their workers to work from home offices or spaces where they can co-work. Employees will, therefore, become flexible and will save more money because of avoiding commuting costs. Through distribution, an organization can employ people with great talents, with the constraint of geographical location or language differences. An example of a company living in the future of work is the Linux Foundation, which has membership from more than 1000 companies all over the world. Linux Foundation meetings involve video conferencing and remote calendars. Team building is done daily, where workers communicate through emails, calls, forums, and other forms of technology.

Open employment

The future of work will not be traditionally-based, where people are hired in a company to work until they resign after getting new jobs. In the modern world, according to the 2016 Gallup Report, millennials like to job-hop from company to company, because they are always looking for new job opportunities in new companies (Hoffman 47). This has turned 57.3 million American youths into freelancers, which is 36% of the American workforce. This means that the percentage of youths to employ is decreasing, which has led companies to come up with new strategies for the future business market.

The future of work involves organizations being more fluid in their terms of employment. Many companies are hiring youth as part-time employees, independent contractors, advisors, and consultants. In the new work setting, there is a whole network of contract and part-time workers, working based on the needs of projects in an organization and coming to work based on their preferences. An example of a company that has already implemented this setting is the management consultancy company called SYPartners, which has both full and part-time employees, and the company has several freelancers. When the company has new projects, it hires people with expertise in the project in question, after which they are dismissed at the end of the project.

The appearance of Monopolistic Companies

The future of work will also involve people witnessing the emergence of big companies that will have better quality than the existing businesses, and the companies will appear to be operating in a monopolistic system. A large group of satisfied consumers then characterizes such companies. An example of a large company that has already dominated the market is Uber (Merkert 49). The main characteristic of these companies is to pop up in places where the traditional or the standard version of their work did not exist. For instance, taxis were rarely found in poor neighborhoods or areas where accommodation was not easily found. Uber, other than joining the car-ride business, has improved service quality and made traveling more flexible, rendering the traditional taxi business ineffective

Preparing the Workforce for the Future of Work

The future of work mostly involves the use of technology, whose adoption in organizations gives the workers a bleak future. Therefore, before preparing their workers for a shift from the standard work arrangement, organizations first convince their workers that technology will be a form of deliverance, helping them have a more productive, brighter future. Organizations convince their workers of the importance of the future of work to make them open towards what they will be taught about the changes in the Organization. Some of the ways that employees are prepared for the future of work are discussed below

Developing Leadership skills

The future of work will require workers to be aware of to be inspirers, regardless of whether they are leaders or not. In the future, these workers will be required to guide new workers in organizations. Many companies seek to develop leadership skills among the youth to prepare them for leadership positions at higher levels after the senior employees have retired.

The best approach in developing leadership skills is to allow employees to be leaders at any capacity, regardless of how minor it is. For example, they can be in charge of running company projects or welfare groups, where they help solve issues in the workplace. Practicing leadership skills will make them more confident, and eventually skilled enough to assume significant leadership roles.

Learning to use Technology

Embracing technology is in the future of work, which makes it compulsory for every worker to be well versed with technology. Employees at all levels are prepared to embrace technology by teaching them about communication, operations, and insight. The organization provides technological gadgets to employees, such as computers, where they are trained on how to send emails, make calls, and other common forms of technology within the company. Showing employees that technology is not a competition or their enemy will encourage them to learn, therefore making their work easier.

Create Continuous learning Opportunities

Evolving of employees will be required as technology changes. Organizations have to instill a growth mindset among their employees to create room for growing (Claro, David, and Carol 8665). Employees are encouraged to develop their skills and be more creative in their work. Hard work, new strategies, and input are some of the methods that employers use to improve the learning opportunities of the employees. Employees with a growth mindset can learn, feel more empowered, and committed in their work.

The future of work has people’s best interests, because they become more flexible, and they can work how they see comfortable. Workers can choose to be full or part-time employed, or they can work from home. The future of work does not only involve replacing human labor with technology, but also enhancing the skills of workers. If a worker loses their job because of technology, the skills that they learned from the organization will enable them to get employment at another skill level.

Works Cited

Claro, Susana, David Paunesku, and Carol S. Dweck. “Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113.31 (2016): 8664-8668.

Franck, Edwiygh. “Distributed Work Environments: The Impact of Technology in the Workplace.” Handbook of Research on Human Development in the Digital Age . IGI Global, 2018. 427-448.

Hoffman, Blaire. “Why Millennials Quit.” Journal of Property Management 83.3 (2018): 42-45.

Merkert, Eugene. “Antitrust vs. Monopoly: An Uber Disruption.” FAU Undergraduate Law Journal 2 (2015): 49.

Wang, Fei-Yue. “Toward a revolution in transportation operations: AI for complex systems.” IEEE Intelligent Systems 23.6 (2008): 8-13.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Nudge: Improving Decisions, Book Review Example

Introduction to Communication, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

The Future of Work

- Climate Solutions

- Commencement 2024

The global pandemic changed the way we work and how our workplaces function. Our experts investigate what changes may be here to stay and what else to expect in the future.

The future is calling

Work is beginning to look very different across all fields and around the globe.

Will we all go back? Will they ever be the same?

What can we learn from the pandemic?

Internships

How can we make them more equitable?

What will digital health care look like?

Can technology help farmers connect to their customers?

Is the open office a thing of the past?

Which skills have staying power in this rapidly changing market?

Global talent

How do you attract talent from around the world?

Legal professionals

Will online litigation help our clogged courts?

What is “The Great Resignation”?

Harvard economist Lawrence Katz explains some of the factors that led to the highest quit rate in US history.

Well-being at work

Business owners, employees, and researchers are looking at ways to make workplaces safer and healthier.

Predictable scheduling

Requiring more notice in scheduling for hourly workers results in more predictable shifts and increased stability for workers, which also leads to improvements in worker well-being, sleep quality, and economic security.

Air quality

The air quality in an office can have significant impacts on employees’ cognitive function, including response times and ability to focus, and it may also affect their productivity, according to new research.

Worker safety and health

COVID-19 forced companies to act quickly and decisively to keep workers safe, and employers have had to adapt new business processes and address existing structures that are lacking.

Flexibility

While working from home, employees have enjoyed an unprecedented sense of agency and autonomy. Contrary to some expectations—but consistent with years of research—that flexibility has actually spurred worker productivity to improve.

For a broader view on workplace innovations, explore the work of our experts from a variety of institutes and centers including:

- The Project on Workforce

- GrowthPolicy

- Harvard i-lab

- Center for Work, Health, & Well-being

- Corporate Responsibility Initiative

- Labor and Worklife Program

- Working Knowledge

- The Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness

Harvard Business School

Managing the future of work

Co-chaired by William R. Kerr and Joseph B. Fuller, this project explores solutions and adaptations to rapid technological change, shifting global product and labor markets, evolving regulatory regimes, outsourcing, and the fast emergence of the gig economy.

Learn more from the Business School

Explore the podcast

Harvard Kennedy School

Reimagine the world of work

Experts investigate ways to help workers gain new skills, get companies to drop outdated practices, and other forward thinking ideas.

Learn more from the Kennedy School

Graduate School of Education

Reshaping work

Experts discuss how the pandemic is altering jobs and careers and how education can respond.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Related In Focus topics

- Coronavirus

- The Accessible World

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Future of Work

Will your company adapt, or be left behind?

How the Cloud Is Changing Data Science

Here’s what leaders need to know in this shifting landscape.

Peter Wang November 02, 2023

The Radical Reshaping of Global Trade

- Rita McGrath

Building Consensus Around Difficult Strategic Decisions

- Scott D. Anthony

- Natalie Painchaud

- Andy Parker

How AI Can Help Leaders Make Better Decisions Under Pressure

- A. Mark Williams

Is Your Job AI Resilient?

- David L. Shrier

- Julian Emanuel

- Marc Harris

Navigating Mental Health in a Multigenerational Workplace

- Morra Aarons-Mele

Old Formulas Won’t Help You Solve Today’s Business Problems

- Andrea Belk Olson

Creating a Happier Workplace Is Possible — and Worth It

- Jennifer Moss

- Previous 1 2 3 4 Next

Personalize Your IT Service Delivery With Persona Mapping

Persona-Powered Onboarding for Better Employee Engagement and Retention

- Previous 1 Next

- Yale University

- About Yale Insights

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

What’s the Future of Work?

Mix smart machines, businesses as platforms, and diverse teams solving complex problems, add a whole lot of uncertainty, and you have a recipe for the future of work. Jeff Schwartz ’87, a principal at Deloitte, discusses how leaders can navigate fast-approaching opportunities and challenges.

- Jeff Schwartz Principal, Deloitte Consulting

The robots are coming! A Pew Research Center survey found that 72% of Americans are concerned about robots and computers taking jobs currently done by humans—though just 2% report having actually lost a job to automation.

In a conversation with Yale Insights last year, Yale SOM labor economist Lisa Kahn said that the effects of automation are already being felt throughout the economy. In fact, the Great Recession likely accelerated the process, both by slowing demand, giving firms a chance to retool without losing sales, and by providing an excuse to lay off unproductive workers.

“We have seen the influences of automation in almost every pocket of the labor market, from the very low end of the skill spectrum to the very high end,” she said. “The future of labor essentially comes down to, where are computers going to replace us and where are computers going to augment us?”

The New Yorker said that economists have long believed that technological changes eliminate some jobs but create plenty of new ones to replace them. Now they aren’t so sure. MIT’s David Autor has found that automation fundamentally alters the supply-and-demand equilibrium. “A subset of people with low skill levels may not be able to earn a reasonable standard of living based on their labor,” he told the magazine. “We see that already.”

So what does it take to keep a job? Kahn’s research has shown that cognitive and social skills are key: “If you have one of them, and especially both of them, I think it’s very likely that you’re going to be pretty safe from automation for a long time.”

To find out more about the future of the work, and how artificial and human intelligence can co-exist in the office, Yale Insights talked with Jeff Schwartz ’87, a principal for Deloitte Consulting and the company’s global lead for human capital marketing, eminence, and brand. Q: What are the key forces shaping the future of work?

Two megatrends are driving the future of work. One is that organizations are being dramatically reoriented and restructured. The historical view of an organization as a hierarchy is being replaced by a view of the organization as a network or an ecosystem. Instead of divisions, functions, or processes, organizations are increasingly being built around teams.

The second big shift has to do with work itself changing. An increasing number of tasks are being accomplished through automation or cognitive computing. To simplify it greatly, if we can articulate the process of something, we can automate it. It’s my expectation that in the next five to ten years everyone will be working next to and with a smart machine they’re not working with today.

Q: What is the role of people in this emerging future?

The question that we’re looking at in every company and every industry is, what are the essential and enduring human skills? What are the things that smart machines can’t do? I’m not quoting it correctly, but Pablo Picasso said something like, “Calculating machines are useless. They can only give you answers.” Asking questions is an essential human skill. I’m not talking about the kind of questions a chat bot can manage. I’m talking about the sorts of creative thinking and inquiry that lets us frame a problem.

For a range of reasons, the problems facing businesses and the public sector are much more complex and multi-disciplinary. The complexity of the problems and the pace of change means we need to work collaboratively, on teams. Working in teams is itself an essential human skill.

The relationship that we're developing with smart machines is different than before. We’re getting a glimpse beyond the digital native to the AI native who doesn't think twice about talking to their phone or any other device. We're getting to the point where natural language interaction—talking to our machines, our machines talking to us—is rebalancing work roles and the ways machines and people can augment each other.

Q: What does it look like to team with smart machines?

Let me offer two examples. Both have been highly popularized, so they should be in some sense familiar. One is IBM’s Watson platform as it relates to medicine. The way the IBM team put it is that after Watson won Jeopardy they sent it to medical school. That meant they fed Watson medical journal articles and data. They developed its capability to read radiology reports and to do oncology diagnoses. At this point, in terms of diagnosis accuracy, the average doctor is around the 50th percentile while Watson is 75th percentile.

Additionally, there’s an explosion of knowledge and data. A really great physician can read a couple hundred journal articles a year, but in any particular field there are thousands of articles written. Teaming with a machine learning technology like Watson could bring all that technical information to bear in diagnosis and coming up with potential treatments while doctors decide on the most appropriate approach and explain to a patient what a diagnosis means, something that currently is very difficult for a machine.

A very different industry, financial services, offers another example. My colleagues Tom Davenport and Jim Guszcza wrote about this recently in the Deloitte Review . One of the examples they use is robo-advisors. They are algorithms, basically, to help create financial portfolios.

Some investors interact directly with robo-advisors online. But many consumers are more comfortable interacting with a person. The financial advisor can still leverage the algorithm’s ability to do the calculations involved in setting up portfolios that meet the desired criteria while focusing on how she or he relates to the customer and ultimately working with more customers.

What these two examples have in common is that there are parts of knowledge work—data sorting, pattern matching, or algorithmic calculations—suited to the machines on our team. Other things are suited to the people on our team. The idea is to work together to augment each other.

Q: How are organizations changing?

What’s an organization going to look like in the 21st century? I think it’s up for grabs. Ronald Coase won his Nobel Prize for telling us in the late 1930s that firms were largely based on transaction costs. Our ability to transact and interact on internet-based platforms has blown away some of our concepts about transaction costs. Work and jobs are being separated from companies because there’s something competing with the traditional corporate organizational form, which is platforms. Beyond thinking about the key design principles of teams, networks, and ecosystems, we need to explore what it means to be a platform-based organization and what it means to be an asset-light organization.

It’s a taxi cab company taking out ads in the Yellow Pages, hiring dispatchers and drivers, and maintaining a fleet of taxis versus Uber, which owns no cars and doesn’t have any drivers. All they have is a platform that connects people that need rides and people that want to provide rides.

The boundaries of organizations in the 21st century are going to be shaped by companies that are the intermediaries between producers and consumers. Or, for many of us today, the platforms that let us constantly shift back and forth between being producers and consumers.

Q: So much of the discussion seems to split the future into either robopocalypse or techno-utopia? Is it that much of a binary?

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” an essay on the future of work. He envisioned that within 100 years the average person would be working 15 hours a week, and we’d have an excessive leisure problem. Obviously, that’s not what happened.

Keynes was a brilliant economist, but he missed something . He missed the number of new fields and human endeavors that would be invented—modern health care, education, and the technology industries, for a start. That’s largely what has driven employment and progress. That’s one of the things that make many of us who are looking at the future of work optimistic. The future doesn’t have to be about grinding out efficiency; it can be about exponential innovation.

It’s less a question of whether robots take our jobs, and more a question of how robots and technology will change our jobs. Automation, and not just robotics, but cognitive technology and AI, natural language processing, and machine learning will take some jobs while also creating new ways of working and extended labor platforms. I think it’s reasonable to expect that all of our jobs and all of our careers will be significantly or fundamentally changed by technology and different labor options.

As that is happening, we have the opportunity to redesign organizations, work, and how we think about careers and learning. If you’re motivated by the idea of living in fast-changing times, it’s going to be pretty exciting. If you’re in fear of fast-changing times, it’s going to be tough.

Q: Today’s cars are huge improvements over Ford’s Model T, but they aren’t so different that we can’t trace the lineage. To what degree have we seen where today’s technology and innovations will take us?

The short answer is, I don’t know. But I agree with William Gibson, who says the future is here, it’s just unevenly distributed. I’m not sure we know what today’s equivalent of the Model T is yet. If we could identify the Model T, the thing that we will incrementally improve far into the future, then we could extrapolate out.

I do think we have an idea of what the 21st century’s drivers might be. Mass production was the driver that enabled the Model T. Platforms, and the way that we interact in the economy, may be one primary driver for the 21st century.

In the early 1960s, Gordon Moore postulated basically that computing power doubles every 18 to 24 months. We’re now 25 to 30 turns into Moore’s Law. When you move something exponentially 25 or 30 turns, every additional doubling is a massive increase in computing and processing power. It makes possible things that simply were not imaginable, economically or technologically, before. We’re applying that to so many domains right now, it’s hard to know where that will go, but exponential technology is a likely another driver.

A third potential driver is in some ways the opposite of the Model T: extreme customization through technologies like additive manufacturing, where the setup costs for creating a different item is practically zero, so that we can both mass customize and mass produce. I think the 21st century will be in some way driven by platforms, exponential technology, and mass customization.

But the fourth driver, which is probably the biggest, is uncertainty and surprise. I was struck by the Queen of England asking after the financial crisis how all the brilliant economists in the UK and around the world, how the profession as a whole, missed something as big as the financial crisis. I think there’s some element of this now in every field. The interaction of highly complex global systems with the uncertainty and unpredictability of human behavior on a massive scale creates the potential for surprise that can happen extremely quickly and be very pervasive. I think that’s only going to continue. It may be fascinating or terrifying—probably a little bit of both.

I don’t think we have yet seen the potential and positive disruption of exponential technologies and platforms play out. I think the next 20 or 30 years will be about new technologies and platforms coming online, but also about adoption and pervasiveness as these ideas work their way into the economy.

Q: What does this mean for individuals?

Learning is the job in the 21st century. Full stop. As Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott at London Business School tell us in The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity , right now, we’re living on average into our 80s, but millennials can expect to live to 100. What does it look like when the average time in a job is four and a half years and the half-life of a learned domain skill, like a computer language, is five years? How many careers are you going to have?

Adaptability and continual learning are not among the core skills; they are the core skills. Learning new domain knowledge is important, but we can learn it relatively quickly and we can access it highly effectively by collaborating with smart machines. More importantly we need to develop essential human skills, and we need the skills and capacities that let us partner in a team with machines. Individuals and companies need to be organizing around learning. And the learning needs to be organized around dynamism and change at speed.

Individuals have a responsibility for maintaining and developing their own skills and retooling through lifelong learning. Businesses will be benefited by being thoughtful about how they redesign jobs and teams and find ways to facilitate learning. But there is a significant set of responsibilities for government, public policy, and social institutions.

Q: What should that look like?

I recently co-wrote an article titled “ Navigating the Future of Work ” with John Hagel and Josh Bersin. Our observation is that if work is being augmented by on- and off-balance-sheet workers along with machines, in order to benefit from the incredible exponential power of technology and get our arms around the challenges that come along with it, we need to consider how we support people in these different arrangements.

Part of that is helping people through economic transitions. That includes healthcare and different kinds of income insurance. We are going to need really good data on people in a gig economy, so we need to improve the data that we gather on employment, education, and skills.

We need to recognize that each of us will need to do some version of going back to school every decade. We need to ask fundamental questions about how communities, cities, states, and the federal government support that. We need to look at every segment of the population and ask the question: what types of tuition credits, tax credits, or new forms of community college would incentivize people to educate themselves? That includes people in their 50s, 60s, and increasingly people in their 70s and beyond.

Q: Nearly every era thinks the challenges it faces are different. Is this time different?

We all decide every day, as students, employees, as business and government leaders: are we seeing incremental or exponential and transformative change? Are you going to bet on marginal changes during the life of your career, or are you going to bet on the world changing quite significantly? Will all the jobs be taken by machines or will more new jobs be created in your life than we’ve seen in the last couple of thousand years? We’re all dealing with those questions every day.

I don’t have the answers, but I do have two daughters who are 23 and 25. I’m hopeful about what might be in front of them and what will be in front of our grandchildren. It’s going to be a wild ride. The things that we’re talking about, exponential technology, platforms, uncertainty driven by the interconnectedness of the global economy and global systems can make wonderful things happen, and there will also be real difficulties.

- Global Business

- Competitive Strategy

The bright future of working from home

There seems to be an endless tide of depressing news in this era of COVID-19. But one silver lining is the long-run explosion of working from home. Since March I have been talking to dozens of CEOs, senior managers, policymakers and journalists about the future of working from home. This has built on my own personal experience from running surveys about working from home and an experiment published in 2015 which saw a 13 percent increase in productivity by employees at a Chinese travel company called Ctrip who worked from home.

So here a few key themes that can hopefully make for some good news:

Mass working from home is here to stay

Once the COVID-19 pandemic passes, rates of people working from home will explode. In 2018, the Bureau of Labor Statistics figures show that 8 percent of all employees worked from home at least one day a week.

I see these numbers more than doubling in a post-pandemic world. I suspect almost all employees who can work from home — which is estimated at about 40 percent of employees — will be allowed to work from home at least one day a week.

Why? Consider these three reasons

Fear of crowds.

Even if COVID-19 passes, the fear of future pandemics will motivate people to move away from urban centers and avoid public transport. So firms will struggle to get their employees back to the office on a daily basis. With the pandemic, working from home has become a standard perk, like sick-leave or health insurance.

Investments in telecommuting technology

By now, we have plenty of experience working from home. We’ve become adept at video conferencing. We’ve fine-tuned our home offices and rescheduled our days. Similarly, offices have tried out, improved and refined life for home-based work forces. In short, we have all paid the startup cost for learning how to work from home, making it far easier to continue.

The end of stigma

Finally, the stigma of working from home has evaporated. Before COVID-19, I frequently heard comments like, “working from home is shirking from home,” or “working remotely is remotely working.” I remember Boris Johnson, who was Mayor of London in 2012 when the London Olympics closed the city down for three weeks, saying working from home was “a skivers paradise.” No longer. All of us have now tried this and we understand we can potentially work effectively — if you have your own room and no kids — at home.

Of course, working from home was already trending up due to improved technology and remote monitoring. It is relatively cheap and easy to buy a top-end laptop and connect it to broadband internet service. This technology also makes it easier to monitor employees at home. Indeed, one senior manager recently told me: “We already track our employees — we know how many emails they send, meetings they attend or documents they write using our office management system. So monitoring them at home is really no different from monitoring them in the office. I see how they are doing and what they are doing whether they are at home or in the office.”

This is not only good news for firms in terms of boosting employee morale while improving productivity, but can also free up significant office space. In our China experiment, Ctrip calculated it increased profits by $2,000 per employee who worked from home.

Best practices in working from home post pandemic

Many of us are currently working from home full-time, with kids in the house, often in shared rooms, bedrooms or even bathrooms. So if working from home is going to continue and even increase once the pandemic is over, there are a few lessons we’ve learned to make telecommuting more effective. Let’s take a look:

Working from home should be part-time

I think the ideal schedule is Monday, Wednesday and Friday in the office and Tuesday and Thursday at home. Most of us need time in the office to stay motivated and creative. Face-to-face meetings are important for spurring and developing new ideas, and at least personally I find it hard to stay focused day after day at home. But we also need peaceful time at home to concentrate, undertake longer-term thinking and often to catch-up on tedious paperwork. And spending the same regular three days in the office each week means we can schedule meetings, lunches, coffees, etc., around that, and plan our “concentration work” during our two days at home.

The choice of Tuesday and Thursday at home comes from talking to managers who are often fearful that a work-from-home day — particularly if attached to a weekend — will turn into a beach day. So Tuesday and Thursday at home avoids creating a big block of days that the boss and the boss of the boss may fear employees may use for unauthorized mini-breaks.

Working from home should be a choice

I found in the Ctrip experiment that many people did not want to work from home. Of the 1,000 employees we asked, only 50 percent volunteered to work from home four days a week for a nine-month stretch. Those who took the offer were typically older married employees with kids. For many younger workers, the office is a core part of their social life, and like the Chinese employees, would happily commute in and out of work each day to see their colleagues. Indeed, surveys in the U.S. suggest up to one-third of us meet our future spouses at work.

Working from home should be flexible

After the end of the 9-month Ctrip experiment, we asked all volunteers if they wanted to continue working from home. Surprisingly, 50 percent of them opted to return to the office. The saying is “the three great enemies of working from home are the fridge, the bed and the TV,” and many of them fell victim to one of them. They told us it was hard to predict in advance, but after a couple of months working from home they figured out if it worked for them or not. And after we let the less-successful home-based employees return to the office, those remaining had a 25 percent higher rate of productivity.

Working from home is a privilege

Working from home for employees should be a perk. In our Ctrip experiment, home-based workers increased their productivity by 13 percent. So on average were being highly productive. But there is always the fear that one or two employees may abuse the system. So those whose performance drops at home should be warned, and if necessary recalled into the office for a couple of months before they are given a second chance.

There are two other impacts of working from home that should be addressed

The first deals with the decline in prices for urban commercial and residential spaces. The impact of a massive roll-out in working from home is likely to be falling demand for both housing and office space in the center of cities like New York and San Francisco. Ever since the 1980s, the centers of large U.S. cities have become denser and more expensive. Younger graduate workers in particular have flocked to city centers and pushed up housing and office prices. This 40-year year bull run has ended .

If prices fell back to their levels in say the 1990s or 2000s this would lead to massive drops of 50 percent or more in city-center apartment and office prices. In reverse, the suburbs may be staging a comeback. If COVID-19 pushed people to part-time working from home and part-time commuting by car, the suburbs are the natural place to locate these smaller drivable offices. The upside to this is the affordability crisis of apartments in city centers could be coming to an end as property prices drop.

The second impact I see is a risk of increased political polarization. In the 1950s, Americans all watched the same media, often lived in similar areas and attended similar schools. By the 2020s, media has become fragmented, residential segregation by income has increased dramatically , and even our schools are starting to fragment with the rise of charter schools.

The one constant equalizer — until recently — was the workplace. We all have to come into work and talk to our colleagues. Hence, those on the extreme left or right are forced to confront others over lunch and in breaks, hopefully moderating their views. If we end up increasing our time at home — particularly during the COVID lock-down — I worry about an explosion of radical political views.

But with an understanding of these risks and some forethought for how to mitigate them, a future with more of us working from home can certainly work well.

Related Topics

More publications, standard setting: should there be a level playing field for all frand commitments, gains from trade: lessons from the gaza blockade 2007-2010, work and pleasure; investigating the rise of digital nomads in mexico.

Essays About Work: 7 Examples and 8 Prompts

If you want to write well-researched essays about work, check out our guide of helpful essay examples and writing prompts for this topic.

Whether employed or self-employed, we all need to work to earn a living. Work could provide a source of purpose for some but also stress for many. The causes of stress could be an unmanageable workload, low pay, slow career development, an incompetent boss, and companies that do not care about your well-being. Essays about work can help us understand how to achieve a work/life balance for long-term happiness.

Work can still be a happy place to develop essential skills such as leadership and teamwork. If we adopt the right mindset, we can focus on situations we can improve and avoid stressing ourselves over situations we have no control over. We should also be free to speak up against workplace issues and abuses to defend our labor rights. Check out our essay writing topics for more.

5 Examples of Essays About Work

1. when the future of work means always looking for your next job by bruce horovitz, 2. ‘quiet quitting’ isn’t the solution for burnout by rebecca vidra, 3. the science of why we burn out and don’t have to by joe robinson , 4. how to manage your career in a vuca world by murali murthy, 5. the challenges of regulating the labor market in developing countries by gordon betcherman, 6. creating the best workplace on earth by rob goffee and gareth jones, 7. employees seek personal value and purpose at work. be prepared to deliver by jordan turner, 8 writing prompts on essays about work, 1. a dream work environment, 2. how is school preparing you for work, 3. the importance of teamwork at work, 4. a guide to find work for new graduates, 5. finding happiness at work, 6. motivating people at work, 7. advantages and disadvantages of working from home, 8. critical qualities you need to thrive at work.

“For a host of reasons—some for a higher salary, others for improved benefits, and many in search of better company culture—America’s workforce is constantly looking for its next gig.”

A perennial search for a job that fulfills your sense of purpose has been an emerging trend in the work landscape in recent years. Yet, as human resource managers scramble to minimize employee turnover, some still believe there will still be workers who can exit a company through a happy retirement. You might also be interested in these essays about unemployment .

“…[L]et’s creatively collaborate on ways to re-establish our own sense of value in our institutions while saying yes only to invitations that nourish us instead of sucking up more of our energy.”

Quiet quitting signals more profound issues underlying work, such as burnout or the bosses themselves. It is undesirable in any workplace, but to have it in school, among faculty members, spells doom as the future of the next generation is put at stake. In this essay, a teacher learns how to keep from burnout and rebuild a sense of community that drew her into the job in the first place.

“We don’t think about managing the demands that are pushing our buttons, we just keep reacting to them on autopilot on a route I call the burnout treadmill. Just keep going until the paramedics arrive.”

Studies have shown the detrimental health effects of stress on our mind, emotions and body. Yet we still willingly take on the treadmill to stress, forgetting our boundaries and wellness. It is time to normalize seeking help from our superiors to resolve burnout and refuse overtime and heavy workloads.

“As we start to emerge from the pandemic, today’s workplace demands a different kind of VUCA career growth. One that’s Versatile, Uplifting, Choice-filled and Active.”

The only thing constant in work is change. However, recent decades have witnessed greater work volatility where tech-oriented people and creative minds flourish the most. The essay provides tips for applying at work daily to survive and even thrive in the VUCA world. You might also be interested in these essays about motivation .

“Ultimately, the biggest challenge in regulating labor markets in developing countries is what to do about the hundreds of millions of workers (or even more) who are beyond the reach of formal labor market rules and social protections.”

The challenge in regulating work is balancing the interest of employees to have dignified work conditions and for employers to operate at the most reasonable cost. But in developing countries, the difficulties loom larger, with issues going beyond equal pay to universal social protection coverage and monitoring employers’ compliance.

“Suppose you want to design the best company on earth to work for. What would it be like? For three years, we’ve been investigating this question by asking hundreds of executives in surveys and in seminars all over the world to describe their ideal organization.”

If you’ve ever wondered what would make the best workplace, you’re not alone. In this essay, Jones looks at how employers can create a better workplace for employees by using surveys and interviews. The writer found that individuality and a sense of support are key to creating positive workplace environments where employees are comfortable.

“Bottom line: People seek purpose in their lives — and that includes work. The more an employer limits those things that create this sense of purpose, the less likely employees will stay at their positions.”

In this essay, Turner looks at how employees seek value in the workplace. This essay dives into how, as humans, we all need a purpose. If we can find purpose in our work, our overall happiness increases. So, a value and purpose-driven job role can create a positive and fruitful work environment for both workers and employers.

In this essay, talk about how you envision yourself as a professional in the future. You can be as creative as to describe your workplace, your position, and your colleagues’ perception of you. Next, explain why this is the line of work you dream of and what you can contribute to society through this work. Finally, add what learning programs you’ve signed up for to prepare your skills for your dream job. For more, check out our list of simple essays topics for intermediate writers .

For your essay, look deeply into how your school prepares the young generation to be competitive in the future workforce. If you want to go the extra mile, you can interview students who have graduated from your school and are now professionals. Ask them about the programs or practices in your school that they believe have helped mold them better at their current jobs.

In a workplace where colleagues compete against each other, leaders could find it challenging to cultivate a sense of cooperation and teamwork. So, find out what creative activities companies can undertake to encourage teamwork across teams and divisions. For example, regular team-building activities help strengthen professional bonds while assisting workers to recharge their minds.

Finding a job after receiving your undergraduate diploma can be full of stress, pressure, and hard work. Write an essay that handholds graduate students in drafting their resumes and preparing for an interview. You may also recommend the top job market platforms that match them with their dream work. You may also ask recruitment experts for tips on how graduates can make a positive impression in job interviews.

Creating a fun and happy workplace may seem impossible. But there has been a flurry of efforts in the corporate world to keep workers happy. Why? To make them more productive. So, for your essay, gather research on what practices companies and policy-makers should adopt to help workers find meaning in their jobs. For example, how often should salary increases occur? You may also focus on what drives people to quit jobs that raise money. If it’s not the financial package that makes them satisfied, what does? Discuss these questions with your readers for a compelling essay.

Motivation could scale up workers’ productivity, efficiency, and ambition for higher positions and a longer tenure in your company. Knowing which method of motivation best suits your employees requires direct managers to know their people and find their potential source of intrinsic motivation. For example, managers should be able to tell whether employees are having difficulties with their tasks to the point of discouragement or find the task too easy to boredom.

A handful of managers have been worried about working from home for fears of lowering productivity and discouraging collaborative work. Meanwhile, those who embrace work-from-home arrangements are beginning to see the greater value and benefits of giving employees greater flexibility on when and where to work. So first, draw up the pros and cons of working from home. You can also interview professionals working or currently working at home. Finally, provide a conclusion on whether working from home can harm work output or boost it.

Identifying critical skills at work could depend on the work applied. However, there are inherent values and behavioral competencies that recruiters demand highly from employees. List the top five qualities a professional should possess to contribute significantly to the workplace. For example, being proactive is a valuable skill because workers have the initiative to produce without waiting for the boss to prod them.

If you need help with grammar, our guide to grammar and syntax is a good start to learning more. We also recommend taking the time to improve the readability score of your essays before publishing or submitting them.

Meet Rachael, the editor at Become a Writer Today. With years of experience in the field, she is passionate about language and dedicated to producing high-quality content that engages and informs readers. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her exploring the great outdoors, finding inspiration for her next project.

View all posts

Deeper Thinking On Work

My writing is an ongoing "conversation" with the ideas that matter to me. Currently writing about: the history of work, unleashing our creative potential, gift economy and books I read. I don't see anything I've written as "finished" so let me know what you think?

Get Started — 14 days FREE!

No credit card required, cancel anytime, no contracts.

Error: Contact form not found.

Who I Write For

- I might not be writing for you

- Experiments In The Gift Economy

- Burning Out At Age 32

- Beanie Baby Curiosity

- Ten Most Surprising Benefits of Self-Employment

- My Awakening: Quitting the Default Path

- Getting Rejected And Landing My Dream Job @ McKinsey

- Decoding High-Performance at McKinsey & Company

- Finding My Passion, My Journey To Unlock My Purpose

Carve Your Own Path

- The 10 "Hustle Traps" to avoid on the creative path

- The New Economy: Tech, Finance, or SOL

- Learn The Game, Don't Become The Game

- Unlocking The Second Chapter Of Success

- Navigating the Pathless Path: Four Stages of the Journey

- Reinvention: 5 Ways To Reinvent Yourself For The Future

- Finding the types of "Prestige" that you actually want

- Beyond Work Sucks: How To Actually Take Action

- The Other Side Of Rest: Taking A Break To Find What Matters

- 10 Career Myths We Should Stop Believing

- The Simple Guide For Starting a Podcast

- Career Transition Playbook

Organizations

- Maslow Didn't Invent The Pyramid

- Deep Dive into Edgar Schein's Theory of Organizational Culture

- The REAL Dark Side Of Consulting: Why Consulting Is A Symptom and Not A Problem

- Chaos Theory: How Companies Can Use Complexity Science To Build Better Futures

- Crisis At Work: Six Reasons Organizations Fail To Unleash Human Potential

- My Reflections On Why McKinsey & Company Is So Successful

Remote Work

- The Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Digital Nomad

- Five Levels Of Remote Work

- Non-Obvious Remote Working Tips

- Facilitating Virtual Sessions

- Interviews: CEO, Doist , CEO, Zapier , Consultant Laurel Farer

Future (History) Of Work

- The emergence of the knowledge worker mind

- Hamsternomics: Rethinking Our Fundamental Economic Future

- Boomer Blockade: How One Generation Reshaped Work

- The Nine Modern School Of Work That Shape Our Beliefs

- It's Time To Retire The Idea of a Steady Career Trajectory

- The Four Day Workweek Is Not About Working Less

- The *Five* Future Of Work Conversations

- Questioning Work: The Unintended Consequences of "Work"

- The Future of Work Mindset Shift

- The Future of Work: What Winning Orgs Will Look Like in 2025

Freelancing & Talent Platforms

- Failed Promise Of Freelance Talent Platforms

- Freelance Consultant Playbook

- Ultimate Guide To Talent Platforms

- Review of Aspiration by Agnes Callard

- Review of Alex Pang's Book Rest

- Review Of "Black Mass" On The Dangers Of Utopia

- All The Things Worth Reading In 2018 (175+ Links)

- John Maynard Keynes Famous 1930's essay "Dreams For My Grandchildren"

- Twelve Lessons From Adam Grant's Originals

- Bullshit Jobs PowerPoint Book Review

2023 Annual Review: New Additions, New Heights & Open Questions

Living Intentionally After “Enough” – Bilal Zaidi on leaving Google, emigrating to the US, the intensity of New York, writing poetry and spoken word, and travel vs. vacations (Pathless Path Podcast)

How To Take A Sabbatical: Stories From Five People Who Took Them

From Rugby to Writer & Book Influencer: How Ben Mercer Reinvented Himself

Ali Abdaal on Identity, Prestige, Quitting Medicine | The Pathless Path Podcast

Kyla Scanlon on the Passion Crisis, Vibecession, and Quitting Her Job To Bet On Herself | The Pathless Path Podcast

Aida Alston: College at 16, Med School in Cuba & Starting Over After Kids | The Pathless Path Podcast

Die With Zero: Why Too Many Save Too Much for Too Late In Their Lives (Book Review)

Luke Burgis on Mimetic Desire, The Three City Problem & Academia | The Pathless Path Podcast

Automation and the Future of Work Essay

Automatization is a broad term that describes all processes that are carried out automatically by software or robots. Robotization, on the other hand, encompasses only that part of the practice where physical machines replace human beings. One of the main benefits of automation is that business efficiency increases and staff costs go down. At the same time, there are also significant disadvantages, such as the inferiority of the technology and the threat of job losses for the real people. However, digging deeper into this topic, it becomes clear that automation and robotization are not acute threats to the workforce and cause far more benefits than detriments.

The automatization process appeared almost immediately with the emergence of manufacturing. However, with the emergence of automation of work processes and its active implementation in almost all areas of human life, there have also been opponents of such a transformation. The Luddite movement in the early 19th century is sometimes attributed to psychological or even religious causes. The workers are portrayed as almost savages who were frightened by incomprehensible machines and tried to destroy them. Still, everything was much simpler than that – the machines endangered the most skilled workers.

In nineteenth-century England, where there were no social security arrangements, wage cuts could easily have been disastrous: workers lost their homes and the means to support their families. Their protest was directed against the injustice symbolized by the machines (Coniff 2). In many ways, their discontent turned out to be prophetic. Britain’s industrialization had benefited the rich and the country as a whole, but it had been a disaster for the workers themselves. Longer working hours, reduced wages, the use of child and women’s labor, and the famous London smog were all direct consequences of the mass proliferation of machine tools. It took a century of hard political and social struggle before factory workers began to benefit at least somewhat from the mechanization of their work.

Nowadays, technophobia is primarily based on the fear that the growth of automation will start to reduce the value of the live workforce or make several professions irrelevant altogether. This does happen for a limited period at each new stage of development (Nova 4). In the past, this temporary negative effect was offset by the general trend. However, in recent years, the situation has started to change. What is fundamentally new is that machines have begun to creep upon intellectual work. Today, people who have spent years of their lives learning are just as likely to lose their jobs as skilled workers were in the past.

Improvements in tools and the adaptation of machines to replace humans in production processes caused an increase in the level of production is recognized as the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. The Industrial Revolution shaped the required conditions for the mechanization of production, primarily in spinning, weaving, metal, and woodworking. Scientists of that time prompted the transition from the use of individual machines to an “automatic machine system.” The conscious function of control remains with man: man becomes close to the process of production as its controller and adjuster. The invention of the automatic steam boiler feed regulator and the centrifugal speed regulator for the steam engine were significant milestones of this period.

Before the 19th century, the study of automatic devices was confined to classical applied mechanics, who regarded them as separate mechanisms. Automation laboratories were created in research institutes of power engineering, metallurgy, chemistry, machine building, municipal services. Technical and economic studies of the importance of automation for industry development in various social conditions were initiated (Vardi 3). The prerequisite for this is the more efficient use of economic resources – energy, equipment, labor, and capital. It improves the quality and homogeneity of production and increases the operational reliability of installations and structures. These inventions brought about significant changes in factory production, railways, and private enterprise. Social changes also appeared – some jobs acquired great prestige in society, while others, on the contrary, declined in demand.

Nowadays, automation is also having a substantial impact on the workforce. This mainly occurs by introducing specific automated processes that were previously carried out by humans (Autor 3). Based on this, some professions may decline in relevance or even disappear altogether due to automatization. In the first instance, these are professions involved in keeping various accounts, such as accountants. With the introduction of automation, it is easy for a computer to do accounting independently. Secondly, professions related to the translation industry may also disappear. Many automated online translators can translate quickly and efficiently, and the number is only growing. Thirdly, occupations associated with the security of premises are in danger of disappearing. Automation has given us high-tech security systems equipped with many cameras and alarms, thus negating the need for a security guard. Therefore, the jobs associated with monotonous, mundane tasks will be eliminated. At the same time, there will be a vast number of new jobs in the world. Experts with rare expertise and skills will be in demand. There will be more free time for creative and intellectual tasks, development, and implementation of new directions and ideas.

Work is ingrained in human life as an integral part of it. The fear of automation, the emergence of Luddism, and the many discussions on the subject have one basis – the fear of losing one of the essential things in our lives – work. The main reason that people need to work – making money for a living – has long been superseded by other equally important factors (Thompson, “Workism is Making Americans Miserable” 4). One of the leading such factors is that people are filled from within through their work. Work gives people a sense of importance and need and allows them to occupy themselves every day and develop (Thompson, “A World Without Work” 7). These days, people need work precisely because it allows them to express their exceptional abilities in a particular field and makes them feel fulfilled.

Based on all of the above arguments and considering the historical background to automation, we can conclude that it is not an acute threat to the workforce. With the disappearance of some jobs, hundreds of other, more creative jobs cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence. With technology advancing relentlessly, automation will be introduced into more and more areas of human life. However, new developments will not be aimed at replacing humans entirely but making life easier and relieving them of routine work. Instead, humans will have far more resources to do creative work and apply their exceptional skills and qualities.

Autor, David H. “Why Are There Still Jobs.” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 29, no. 3, 2015.

Coniff, Richard. “What the Luddites Really Fought Against.” Smithsonian Magazine , 2011.

Nova, Annie. “Automation Threatening 25% of Jobs in the US”. CNBC, 2019. Web.

Thompson, Derek. “Workism is Making Americans Miserable.” The Atlantic , 2019.

Thompson, Derek. “A World Without Work.” The Atlantic , 2015.

Vardi, Moshe Y. “What the Industrial Revolution Really Tells Us About the Future of Automation and Work.” The Conversation , 2017.

- Automation and Its Impact on Employment

- Steam Engine: History and Importance of the Changes of the Industrial Revolution

- Scientific Revolution History: Attitude of Mechanization

- Google Technologies and Their Impact on Society

- Tracking: More Advantages Than Disadvantages?

- The Value of Network Effects

- The Multiple Object Tracking in Surgical Practice

- Smartphones and Generations: Hyper-Connected World

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, October 18). Automation and the Future of Work. https://ivypanda.com/essays/automation-and-the-future-of-work/