Evolution of Language

Language allows us to share our thoughts, ideas, emotions, and intention with others. Over thousands of years, humans have developed a wide variety of systems to assign specific meaning to sounds, forming words and systems of grammar to create languages. Many languages developed written forms using symbols to visually record their meaning. Some languages, like American Sign Language (ASL), are an entirely visual language without the need for vocalizations.

Although languages are defined by rules, they are by no means static, and evolve over time. Some languages are incredibly old and have changed very little over time, such as modern Icelandic, which strongly resembles its parent, Old Norse. Other languages evolve rapidly by incorporating elements of other languages. Still other languages die out due to political oppression or social assimilation, though many dying languages live on in the vocabularies and dialects of prominent languages around the world.

Teach your students how the languages of the world have evolved over time, and how their own languages continue to evolve today with this curated collection of resources.

Social Studies, Anthropology, English Language Arts, World History, Geography

Introduction: Origin and Evolution of Language—An Interdisciplinary Perspective

- Published: 02 May 2018

- Volume 37 , pages 219–234, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Francesco Ferretti 1 ,

- Ines Adornetti 1 ,

- Alessandra Chiera 1 ,

- Erica Cosentino 2 &

- Serena Nicchiarelli 1

19k Accesses

5 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 In Search for a Paradigm: The Origin of Language from Biolinguistics to Embodied Cognition

Anyone who intends to deal with the origins of language should face what critics describe as an inescapable truth: since language does not fossilize, the investigation of its origins should not rely on empirical evidence but merely have a mainly theoretical character. These considerations are at the heart of two well-known edicts— Société de Linguistique de Paris in 1866 and the Philological Society of London in 1872—that forbade all members from presenting speeches on the topic. The arguments underlying these edicts have a strong intuitive character and seem guided by a matter of common sense: it is simply not possible to rewind tape to the starting point; therefore, the origin of language is not empirically analyzable. Everything done relies on speculation, the field (very dangerous, according to many) of philosophy rather than science.

Ostracism imposed by the two Societies have had negative consequences for a long time. However, the contemporary situation is radically different: for many years, research on language origins is in a revival and currently one of the most discussed topics in literature on human communicative capabilities. In addition, the essential feature of ongoing research is the clear prevalence of empirical over theoretical studies (Fitch 2017 ; Wacewicz and Zywiczynski 2017 ). Paradoxical though it may seem, the big issue today is opposite to that raised by the edicts: it is finding the key to the problem of too much available data.

1.1 Interdisciplinarity

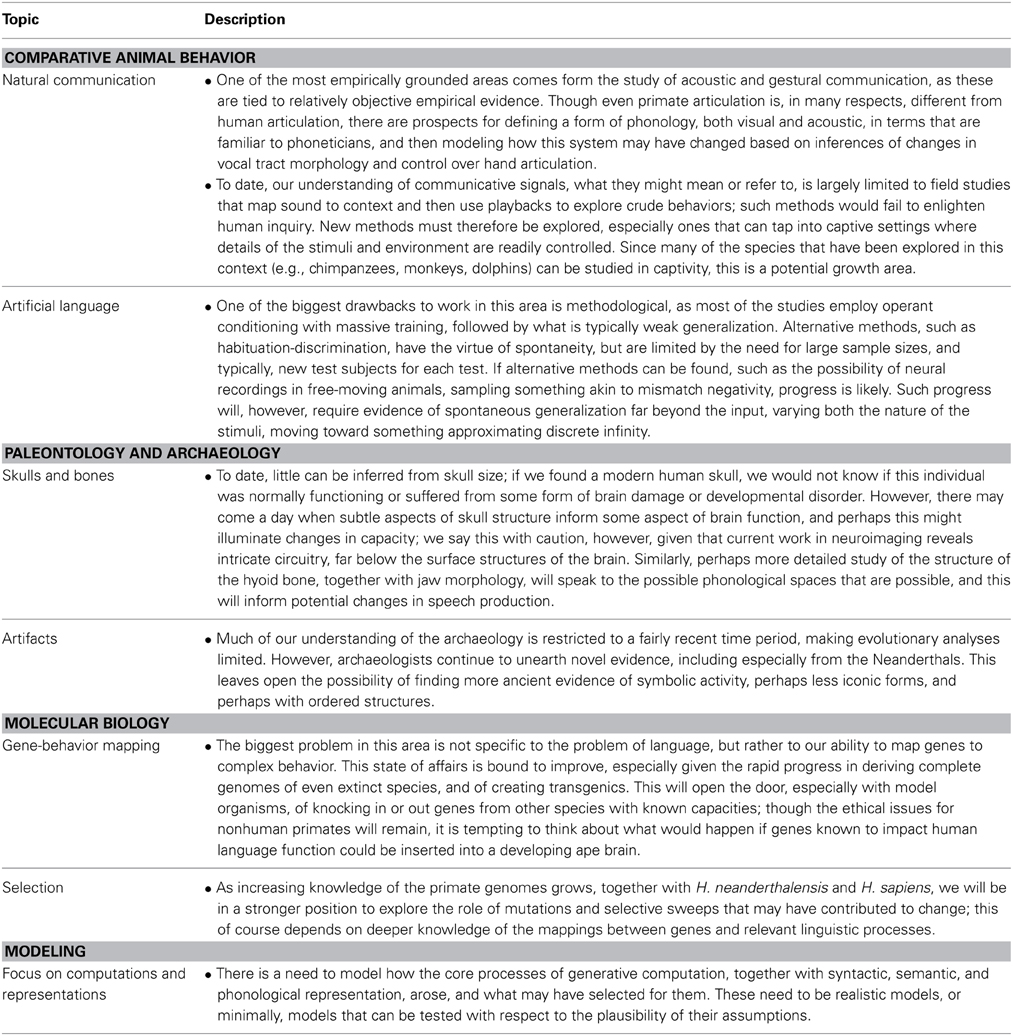

Several disciplines contribute to the discussion on the origin of language: computer simulation, cognitive psychology, genetics, paleoanthropology, and comparative studies, as some examples (see Tallerman and Gibson 2012 ). Some disciplines employ sophisticated analysis techniques resulting in empirical evidence inconceivable until a few years ago. The discovery of mirror neurons—an example from neuroscience to which we will return—was a turning point for studying mechanisms underlying language origin (Rizzolatti and Arbib 1998 ; Arbib 2005 ). Further, mirror neurons are an interpretative key to promote a new research paradigm within this field (Hostetter and Alibali 2008 ; Glenberg and Gallese 2012 ). According to Fitch ( 2017 ), research on paleogenetics represents the time machine allowing us to reconstruct the starting point of human communication. In Fitch’s opinion, “If a single empirical development warrants optimism and excitement about the coming decades of language evolution research, it is these advances in genetics and genomics” (p. 18). Other technologically advanced research areas are computer simulation (Kirby et al. 2014 ) and evolutionary robotics (e.g. Cangelosi 2012 ). Among traditional disciplines, comparative studies on nonhuman species continue to play a major role, specifically comparisons with other primates (e.g., Hewes 1973 ; Pollick and de Waal 2007 ) as well as other species that are phylogenetically distant from Homo sapiens , such as birds (Pfenning et al. 2014 ). Moreover, there is a widespread confront with extinct species of hominins, especially Homo neanderthalensis (Dediu and Levinson 2013 , 2018 ; Mithen 2005 ; Lieberman and McCarthy 2007 ) but also with more ancient forefathers such as Homo ergaster / erectus (Corballis 2002 ; Donald 1991 ). Examples showing the role of empirical studies in the origin of language could multiply but, for present purposes, there is no need to delve further.

What considerations should be made starting from these studies? First, the flourishing of empirical investigations on language origins allows the overturn of common opinion about the entirely speculative character of the topic itself. Assuming a considerably different perspective compared to the past, it is possible to reflect on language origins in terms of an “ongoing transition of scientific research on language evolution from one dominated by speculation and pet hypothesis to ‘normal’ science, marked by attempts to empirically evaluate multiple plausible hypotheses” (Fitch 2017 , p. 3). That said, the huge volume of data available and the heterogeneity of disciplines have had problematic effects on research: each discipline contributing to the study of language is different from another, so the first difficulty is identification of a point of convergence among extremely heterogeneous empirical results. As pointed out by Gong et al. ( 2013 ), the first step in this direction relies on the interdisciplinary character of research. In their view, only a perspective of this kind "based on pooled knowledge from diverse disciplines to reconcile seemingly contrary positions and rule out solutions plausible only within a single discipline, can lead to a biologically plausible, computationally feasible, and behaviorally adequate understanding of language and its evolution" (p. 10).

The available “bewilderingly diverse and voluminous [data] span a set of discipline that no single scholar, however knowledgeable, could hope to individually master” (Fitch 2017 , p. 24). This interdisciplinary approach appears to be an essential step. From a methodological point of view, the interdisciplinary character of a study on language origins is the distinctive feature of current research compared to previous investigation—a feature reflecting the complex and multistratified nature of language.

However, the reference to interdisciplinarity is not enough to overcome a second difficulty—theoretically more relevant—imposed by the “bewilderingly diverse and voluminous” body of evidence. Fitch ( 2017 ) argues that the problem to face “is not with data or hypotheses, but sociological” (p. 6). In his opinion, the partition of knowledges due to multiplying of disciplines has led to a significant mutual suspicion among scholars. Fitch’s considerations should not be underestimated; equally, the issue of theoretical models should not be underrated. Different fields of research communicating with one another require common ground—a shared conceptual space in which to construct connections among the various disciplines. Only within this space could empirical studies build hypotheses, supported by strong inferences, characterizing multidisciplinary research on language origins: “the method of empirically testing the predictions of multiple scientifically plausible hypotheses simultaneously” (Fitch 2017 , p. 6). What identifies strong inferences is included in the word simultaneously , emphasizing the need for a “bird’s-eye view” and the ability to make connections and convergences that cannot be understood from inside each discipline. Construction of a shared conceptual space is possible with a double plan: the plan of the achievements of each discipline and that of building interpretative models capable of providing a unitary perspective on different data. From these considerations follows the difficulty imposed by Fitch’s “bewilderingly diverse and voluminous” body of data, strictly connected to the investigation, selection, and choice of suitable interpretative models.

The flourishing of interpretative models goes hand in hand with the flourishing of empirical disciplines. Countless theoretical proposals stress some specific aspects of language and address the issue of origins from a multidisciplinary perspective. Tomasello ( 2008 ), for example, combines different fields of study and theoretical topics—from the topic of altruism to the issue of the gestural foundation, from the function of intentionality to the role played by specific cognitive systems as mindreading—and proposes the idea that the origin of human communication is connected to specific ways of cooperation of our species. In a similar way, studying the role of systems as temporal and spatial projection in language processing, Corballis ( 2017 ) proposes a model in which studies of cognitive psychology and neuroscience integrate with data from ethology and paleoanthropology. Tomasello and Corballis represent merely two approaches for constructing models capable of proposing a unitary perspective from the contributions provided by different disciplines. That said, the number of models is just as problematic as the amount of empirical data. The effort of constructing a shared conceptual space requires further effort to build more general conceptual research program.

1.2 From Models to Paradigms

Many scholars interested in language origin research (e.g., Bickerton 2012 ; Tattersall this volume) have explicitly assumed Chomsky’s model of language, that of Universal Grammar (UG), which is still relevant in the current debate (e.g., Hauser et al. 2014 ) despite some criticism (e.g., Tomasello 2009 ; Pennisi and Falzone 2016 ; Corballis 2017 ). Biolinguistics is the multidisciplinary enterprise that assumes UG as the reference model (Chomsky 2007 ; Lennerberg 1967 ; Piattelli-Palmarini 1974 ). Referring to UG, biolinguistics has a clear theoretic advantage over competitive interpretative perspectives: a refined and well-established conception of language, the outcome of > 50 years of thinking. A conception of this kind is also valuable from an empirical point of view, such as the illuminating example of investigations aimed at corroborating the principle of structure dependency and the autonomy of syntax (Musso et al. 2003 ). Furthermore, the adhesion to UG has implications for wider conceptual issues that go beyond the reflection on language (e.g., the Cartesian nature of UG affecting the way we conceptualize human nature). For all these reasons, UG represents an ideal reference framework to construct a shared conceptual space in which to interpret data and elaborate hypotheses from different disciplines. UG is more than a conceptual model; it is a genuine interpretative paradigm in the sense used by Kuhn ( 1962 ).

The minimalist turn within this generative paradigm (Chomsky 1995 ) fortifies the idea of UG as a shared conceptual space. In fact, according to some scholars (Benítez-Burraco and Boeckx 2014 ; Boeckx and Benítez-Burraco 2014 ), the minimalist program paved the way for development of biolinguistics 2.0, a theoretical approach that overcomes some difficulties that still characterize classic biolinguistics. Boeckx and Benítez-Burraco ( 2014 ) have suggested that biolinguistics 1.0 is “unable to properly deal with the attested complexity observed at the genetic, neurological, developmental, or even evolutionary level” (p. 10). Instead, biolinguistics 2.0 is a wider and more general research program (a paradigm) that is able to encompass different interpretative models, even those promoted by scholars who do not work within the generative paradigm. Di Sciullo and Boeckx ( 2011 ) state that “biolinguistics (…) allows for the exploration of many avenue of research: formalist; functionalist; nativist and insisting on the uniqueness of the language faculty; nativist about general (human) cognition but not about language per se; etc. From Chomsky to Givon, from Lenneberg to Tomasello, all this is biolinguistics” (p. 5).

In allowing minimalism to launch a new phase within biolinguistics, there is the distinction between faculty of language in the broad sense (FLB) and in the narrow sense (FLN; Hauser et al. 2002 ). Through minimalism, Chomsky moved away from the early “isolationist” view (the idea that language is processed by a specific module) and led the way to a broader-minded perspective in which language functioning is not autonomous from other cognitive systems. The idea of considering language as the broad FLB and not as FLN is a way to explain language functioning through more complex cognitive architectures than those postulated by classic biolinguistics. Furthermore, many cognitive devices characterizing FLB are also present in nonhuman animals; the focus on FLB allows development of a continuistic view of language. In light of these considerations, it seems possible to argue that early Chomsky concerns are outdated regarding the relationship between UG and evolutionary theory (Chomsky 2010 ; Berwick and Chomsky 2015 ). Therefore, the minimalist turn has allowed to again address the taboo question of language origins. As highlighted by Wacewicz and Żywiczyński ( 2014 ), indeed, anything important regarding language origins is ascribable to FLB.

So far, so good. Biolinguistics seems to be an interpretative paradigm able to include in a unitary perspective different theoretical models. Moreover, it offers a shared conceptual space useful in dealing with heterogeneous data that, as we have argued, might represent a risk for the multidisciplinary research on language evolution.

1.3 Uniqueness

Biolinguistics presents several aspects that need to be analyzed. In our opinion, when it comes to the origins of language, the reference to a refined and well-established model of language represents both the strength and weakness of such paradigm. More specifically, the problematic issue is represented by uniqueness —an issue in the Chomskyan perspective that is linked to Cartesian tradition (see for a discussion Ferretti and Adornetti 2014 ). There is no harm in emphasizing traits that differentiate human language from other forms of communication, nor in considering language as the peculiar trait of humans. But what is true for humans must also be true for other animals. As pointed out by Pinker ( 1994 ), the elephant has a type of nose that distinguishes it from all other animals, and the bat uses a distinctive perceptual system to relate to the environment. In such cases, the concept of uniqueness is not a problematic issue because it is consistent with Darwinian continuism and gradualism. The problem arises when the reference to uniqueness is used in support of the idea that is not possible to seek the precursors of language in hominins and species different from Homo sapiens because of a qualitative difference.

There are two possible moves to curtail such a Cartesian drift in the research on language uniqueness. The first is to appeal to the idea that FLB includes some traits shared with other species. According to Fitch ( 2017 ), “Thus, despite the fact that language in toto is unique to our species, most components underlying it are shared, sometimes very broadly and sometimes only with a few other species” (p. 7). Genetic data play a key role in this regard, as the focus on “deep homologies” allows possible comparison with many nonhuman species (see also Fitch 2005 ). According to Fitch ( 2017 ), indeed, narrow comparative approaches must be extended because “there is a rising awareness that distant relatives like birds may have as much, or more, to tell us about the biology and evolution of human traits as comparisons with other primates” (p. 6).

The second move against the Cartesian notion of uniqueness is showing that language emerged outside Homo sapiens . This considers the communication systems of our species’ ancestors as possible precursors of language. Consistent with that, some authors suggest that language arose in Homo heidelbergensis (Dediu and Levinson 2013 ) or in Homo ergaster–erectus (Corballis 2002 ; McBride 2014 ), while some others consider language even more ancient (Shaw-Williams 2017 ). In such a framework, the hardest debate is focused on the linguistic abilities of Homo neanderthalensis . The view by (Lieberman 1975 ; Lieberman and McCarthy 2007 ) according to which Neanderthals had no articulatory capacity to speak has been the prevailing perspective for a long time (e.g., Bickerton 1990 ). New data from different disciplines (e.g., paleoanthropology, archaeology, genetics) are now challenging this view (for an overview, see Fitch 2010 ; Dediu and Levinson 2013 , 2018 ) paving the way to building a gradualist scenario. In fact, according to Dediu and Levinson ( 2013 ), modern humans, Denisovan and Neanderthal share a common genetic line that can be considered the basis of language.

Two considerations are worthy: the first concerns considering the specificity of language in the more general framework of continuism; claiming that modern language is in continuity with more ancient forms of communication does not mean overlooking those specificities that characterize language as we know it today. The second consideration is that, despite elements of continuity attributed to the traits of FLB, the crux of language is still represented by FNL, namely by “those traits that are unique to humans and unique, within humans, to language itself” (Fitch 2017 , p. 5; see also Fitch 2005 ; Hauser et al. 2002 ). Ascribing such traits to language means asserting that its essential elements (what makes it “language”) are related to unique features with no precursors in the animal kingdom. Thus, continuity with other animals and other species of hominins applies only to those aspects of language that are not linked to FLN; that is, those aspects not specifically linguistic.

This is where the strength of biolinguistic paradigm also turns out to be its limitation. The reference to a model of language strongly linked to UG is the crux for authors more willing to revise the notion of uniqueness. Thus, for instance, while criticizing Chomsky for his position on gradualism and continuism, Dediu and Levinson ( 2013 ) defined language “as the full suite of abilities to map sound to meaning, including the infrastructure that supports it (vocal anatomy, neurocognition, ethology of communication)—FLB or ‘faculty of language broad’ in the sense of Hauser et al. ( 2002 )” (p. 2). Considering that syntax is the mechanism underlying the mapping between sound and meaning (Jackendoff 1993 ), FLN then paves the way for the issue of uniqueness. According to Fitch ( 2017 ), “without hierarchical syntax, we would not have modern language [because] without this fundamental characteristic, our open-ended ability to map novel thoughts onto understandable signals would be impossible” (pp. 10–11). At the base of this kind of considerations there is a definition of language in terms of “a complex faculty that allows us to encode, elaborate and communicate our thoughts and experiences via words combined into hierarchical structures called sentences” (Fitch 2017 , p. 7). Although investigations on the communicative abilities of animals such as birds, distant from Homo sapiens , have shown their capacity to combine elements in a rule-governed manner (a basic phonological “syntax” of birdsong), such a capacity is considered insufficient to reach the human phrasal syntax and semantics.

From these considerations follows that the syntactic component (rather than vocal or semantic-pragmatic ones) is the distinctive trait of language when comparing it to animal communication. Distinguishing our way of communication from that of other animals is crucial to the issue of language origins. Not under discussion is the fact that the topic of emergence of syntax is a main problem in the agenda on the studies of language origins. Instead, the point at issue is whether the topic of language origins should coincide with the topic of the origin of syntax: in other words, should syntax be considered the distinctive trait that, in the early stages of language, ensured the transition from animal to human communication? In the next section, we consider this point as the main limit of the well-established model of language promoted by biolinguistics 2.0.

1.4 Compatibilism

In our view, the first attempt made by Pinker and Bloom ( 1990 ) to integrate Chomsky’s model of language in an evolutionary context is an example of the limitations of the biolinguistic paradigm. Assuming UG as the indisputable starting point of the argument, Pinker and Bloom disputed Chomsky in proving UG to be compatible with the theory of evolution. Their proposal was based on the following logical argument: the only successful account of the origin of complex biological structure is the theory of natural selection; language is a complex biological structure (subsequently refuted by minimalism); the origin of language must be explained by the theory of natural selection. This argument led to a new stage in the study of the relationship between UG and evolutionary theory—namely, a compatibilist phase in which the theoretical structure of UG represents the a priori assumption that the empirical research is called to verify. The main goal underlying this compatibilist perspective is finding a model of the theory of evolution that better fits the model of language. This compatibilist attitude, in fact, has characterized Chomsky’s thought development, from the early aversion to evolutionary theory to the recent adhesion to evo-devo approaches centered on the criticism toward Pinker and Bloom’s ( 1990 ) neo-Darwinism (Chomsky 2010 ; Berwick and Chomsky 2015 ).

Relevant to the present article is that this sort of compatibilism also affects the study of language origins. In fact, if the starting point of investigation is the model of language, the analysis of the origin of communication strongly depends on the conclusive outcome of the process. The way in which Berwick and Chomsky ( 2015 ) synthetize the evolutionary steps that in their opinion have led to language provides an example of the implications of adopting this kind of analysis:

We enter here into large and extremely interesting topics that we will have to put aside. Let us just summarize briefly what seems to be the current best guess about the unity and diversity of language and thought. In some completely unknown way, our ancestors developed human concepts. At some time in the very recent past, apparently some time before 80,000 years ago if we can judge from associated symbolic proxies, individuals in a small group of hominids in East Africa underwent a minor biological change that provided the operation Merge—an operation that takes human concepts as computational atoms and yields structured expressions that, systematically interpreted by the conceptual system, provide a rich language of thought. (…). At some later stage, the internal language of thought was connected to the sensorimotor system, a complex task that can be solved in many different ways and at different times (p. 87).

Since language relies on syntax (and since syntax depends on Merge), the evolutionary steps that have led to language should include not only an explanation of how Merge appeared but also a description of how the necessary tools (i.e., concepts) that provided operation Merge have arisen. Despite this, Berwick and Chomsky ( 2015 ) interpret the evolution of Merge in terms of a (casual) biological mutation and assume the emergence of concepts as a given without explaining it. In other words, this way of viewing language directs the evolutionary process.

As we have suggested, biolinguistics can count on a refined and well-established model of language. Because of this, the biolinguistic paradigm can foster hypotheses and predictions in different areas of research that share a common idea on the nature of language. That said, it is certainly true that interpretative paradigms are necessary to organize the large amount of heterogeneous data from different disciplines, but it is also true that choice of the paradigm strongly affects construction of a unitary model of language and its origins. What if the perspective is overturned? What if the theory of evolution (and not the model of language) is the starting point of the analysis? At the base of such change is the idea that language must meet the conformity constraint of the theory of evolution rather than the compatibilist one. This idea paves the way to construction of a new interpretative model of language inspired by Darwin (more than Descartes); for this reason, it is not only plausible but also advisable when considering the question of the origin of linguistic capacity. Following these considerations, the next sections will consider a new paradigm that, unlike biolinguistics, assumes the principles of evolutionary theory as points of reference.

2 Toward a New Paradigm for the Study of Language and Mind: The Embodied Approach

The investigation of human mind within the field of cognitive science has been influenced for a long time by what Hurley ( 1998 ) defined the “classical sandwich model”. The idea is that the external layers of the sandwich, that is, the sensory and the motor are not so important after all, because what matters is the inner layer, the cognitive processes. Furthermore, according to this metaphor, the sensory and the motor are separate, they are just input and output systems, which do not affect what happens at the level of the cognitive processes. This way of understanding the relation between sensory-motor and cognitive processes has also influenced the view on language. Considering the mind as a device that manipulates symbols, symbolic theories of meaning have assumed that linguistic meaning arises from the syntactic combination of mental symbols. This view is often conjoined with a modularist assumption that meaning is processed in an informationally encapsulated way such that these mental symbols are amodal, i.e., largely decoupled from sensory, motor and emotional processes (e.g., Fodor 1975 ; Pylyshyn 1984 ).

This traditional view has been more recently criticised and rejected by the embodied theories of mind, which assume that supposedly “high” processes such as language and thought are grounded in “low” sensory, motor and emotional processes (Barsalou 1999 ; Kemmerer 2010 ; Gallese and Lakoff 2005 ; Prinz 2005 ; Werning 2012 ; Werning et al. 2013 ). According to these theories, in fact, there is no such distinction between “low” and “high” processes, because “[c]ognitive activity takes place in the context of a real-world environment, and it inherently involves perception and action” (Wilson 2002 , p. 626). From this perspective, cognition is grounded, context-dependent, situated, anchored to experience: the organism’s environment has a central role in its behavior (the environment is part of the cognitive system); such environment is not only a rich source of constraints and opportunities for the organism, but also a context that gives meaning to its actions (Beer 2014 ). Furthermore, cognition is for action: “the function of the mind is to guide action, and cognitive mechanisms such as perception and memory must be understood in terms of their ultimate contribution to situation-appropriate behaviour” (Wilson 2002 , p. 626). Focusing on the primacy of action, embodied theories lead to a strong rejection of the traditional cartesian distinction between “knowing how” (execution) and “knowing that” (competence), because all knowledge, not only the “knowing how” is supposed to emerge from doing. Furthermore, the theoretical “knowing that” has not anymore a privileged status as the foundational way of acquiring knowledge. In the following sections we will suggest that these two aspects—grounding and the primacy of action—are important for the building of a model of language alternative to biolinguistics. Precisely, we will argue that: the action system has a crucial role in language evolution and that the acknowledgment of this allows to elaborate perspectives of language emergence in line with the conformity constraint (Sect. 3 ); the embodied approach, supposing a kind of anchoring to the external reality, is suitable to explain a crucial property of human communication, i.e. how language is appropriate to the situation (Sect. 4 ). Before going into details of these arguments, it is necessary to analyze how the embodied account has deeply influenced the way of thinking about language.

According to the embodied theories of mind, language comprehension is based on the multimodal simulation of perceptions, actions, and emotions (e.g., Barsalou 1999 , 2010 ; Gibbs 2006 ; Glenberg et al. 2013 ; Lakoff 1987 ; Pecher and Zwaan 2005 ). Therefore, understanding the meaning of a word like “chair” partially re-activates the brain regions involved in perceiving chairs and the motor areas relevant to interactions with chairs (as well as emotion circuits if the word elicits affective states). This notion of comprehension provides a way of addressing the “symbol grounding problem”, that is, the problem of explaining how symbols can grasp reality and be meaningful (cf. Harnad 1990 ). As revealed by Searle’s Chinese Room Argument (Searle 1980 ), amodal-symbolic theories seem to have difficulties explaining that, given that no matter how many abstract symbols a subject relates to one another, she is never going to determine the meaning of the sentence.

The sciences of mind and brain are currently facing the challenge of accommodating in a unifying framework (a paradigm different than biolinguistics) growing evidence in favour of this embodied model of language. Neuroimaging investigations have supported this view exploring several different domains. For example, in the domain of perception, it has been shown that perceptual brain regions that process object-related information are also activated by as words related to visual features (e.g., “brown”; Pulvermüller and Hauk 2006 ), odours (e.g. “cinnamon”; Gonzalez et al. 2006 ), sounds (e.g., “telephone”; Kiefer et al. 2008 ), and taste (“salt”; Barrós-Loscertales et al. 2012 ). The domain of emotions and pain has also been explored with a variety of methods, including EEG (Rak et al. 2013 ), fMRI (Richter et al. 2010 ) and behavioural measures (Reuter et al. 2017 ), producing converging results that suggest that language processing hinges upon processes that are active when people actually feel emotions and pain.

As for actions, it is known that somatotopic areas in the motor and premotor cortex, which are active when subjects move specific body parts (e.g., “face”, “leg”, “arm”), are also active when they understand action-related words that refer to those body parts (e.g., “lick”, “pick”, or “kick”; Pulvermüller 2005 ) and motion sentences (Tettamanti et al. 2005 ), and the processing of action-related verbs is impaired specifically in patients with degenerative brain diseases that affect the motor system, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Grossmann et al. 2008 ), Parkinson’s disease (e.g., Cotelli et al. 2007 ) and other motor neuron diseases (Bak et al. 2001 ).

Starting from the assumption that people have bodies by means of which they explore the surrounding environment, the embodied theories of mind have argued that there is a relation of mutual inter-dependence between action and perception (Berthoz 1997 ). Perception is indeed action-oriented, as expressed by the notion of “affordances” which, following Gibson ( 1979 ), are defined as properties things have in virtue of being the object of certain potential actions. The neuroscientific plausibility of this notion is supported by the finding that a set of neurons in the premotor cortex called “canonical neurons” respond not only when manipulable objects are actually manipulated but also when they are simply perceived (see for a review Martin 2007 ). Moreover, canonical neurons are also active when tool-related nouns are presented (Cattaneo et al. 2010 ; Marino et al. 2011 ) and behavioural studies confirm that the processing of nouns can interact with motor activity (Tucker and Ellis 2004 ; Lindemann et al. 2006 ). Furthermore, affordances seem to be involved in the construction of sentence meaning. This has been shown by Glenberg and Robertson ( 2000 ) in behavioural studies in which sentences containing affordance violations (e.g., “After wading barefoot in the lake, Erik used his glasses to dry his feet”) were judged as less sensible than semantically and grammatically matched sentences with no violations (e.g., “After wading barefoot in the lake, Erik used his shirt to dry his feet”). Also, using the EEG method, it has been shown that the N400 component of the ERPs is sensitive to the modulation of object affordances as induced by the previous linguistic context (Cosentino et al. 2017 ).

Converging evidence from different disciplines, including psychology, neuroscience, neurolinguistics, and neuropsychology, has informed the theorizing about the embodiment of mind, leading initially some scholars to suggest that a radical shift of paradigm was happening with respect to more traditional amodal-symbolic theories. Currently, most researchers acknowledge that the correct approach lies probably in the between, but the debate is still completely open as to level of embodiment and involvement in different processing stages. Theories of language origin and evolution have been deeply influenced by this interdisciplinary discussion, making the notion of “action” a very important attractor in the theory space concerning how language emerged and evolved. There are at least three levels of involvement of the notion of “action” in explanations of language origin and evolution.

The first, more obvious, way of endorsing the link between action and language from an evolutionary perspective is constituted by the well-represented strand of gestural theories of language evolution. Second, the idea of a strong connection between language and action is the starting assumption of some models of language evolution, which assume that the mechanisms originally evolved for action control might have been exploited for language, at both the grammatical and semantic level (see Glenberg and Gallese 2012 ). This idea has been declined in different ways, but the most representative is maybe the so-called “mirror system hypothesis” (see Arbib et al. 2014 for a review). Finally, the notion of “action” connects theories of language origin and evolution to the so-called motor account of social cognition (e.g., Cosentino 2014 ). This approach addresses the issue of language evolution focusing on the pragmatics of language (see Ferretti 2013 ) and assuming that the ability to read other people’s communicative intentions crucially involves the capacity to understand their actions (Blakemore and Decety 2001 ). In the following sections, we now turn to these different approaches.

3 Evolution of Expressive System from an Interdisciplinary Action-Oriented Perspective

The embodied models discussed in the previous section have important consequences for the question of language origins. The idea that language is grounded in “low” sensory-motor processes has allowed scholars to elaborate bottom-up perspectives of language emergence, which focusing on the constituent capacities underlying larger cognitive phenomena are more in line with evolutionary biology. In other words, embracing a model of knowledge as action permits development of a language model that meets the conformity constraint of the theory of evolution rather than the compatibilist one. Furthermore, adhesion to such a model (setting aside the distinction between competence and execution typical of biolinguistics) allows us to reconsider the fundamental role of the expressive dimension of communication for both the origin and functioning of language. In fact, perspectives that embrace the idea of “language as action” deal with the issue of language origin referring to evolution of the communicative expressive modality. Acknowledgment that the action system has a crucial role in language comprehension and production has provided new views on the involvement of such a system in language evolution, bolstering the gesture-first theory of human communication, according to which human language first originated as a gestural-based communicative system (Arbib 2005 ; Arbib et al. 2008 ; Armstrong and Wilcox 2007 ; Corballis 2010a , b ; Fogassi and Ferrari 2007 ).

The gesture-first theory has taken advantage of the interdisciplinary enterprise that characterizes language evolution research (for a review, see Corballis 2010a ). The first modern effort in this direction was that of anthropologist Hewes ( 1973 ). He reopened the way to the studies on language origins, explaining the origin of human communication in a gestural theoretical framework and synthetizing evidence from primatology (i.e., the success of teaching sign-based communication systems to nonhuman apes; Gardner and Gardner 1969 ), paleoanthropology (the late emergence in human evolution of the full anatomic equipment for vocal production; Lieberman and Crelin 1971 ) and neuroscience (the relationship between handedness and lateralization; Lennerberg 1967 ). Nonetheless, since the 1990s, gestural theory has become a very influential model to account for the origin of human communication. The reason is tied to an important neuroscientific achievement: discovery of mirror neurons in the F5 area of the premotor cortex of the macaque’s brain (di Pellegrino et al. 1992 ; Gallese et al. 1996 ). These neurons are defined as mirror because they allow a kind of mirroring between perception and action. Specifically, they discharge when the monkey performs an intentional act with its hands (e.g., trying to grasp an object) and when it observes another primate (human or monkey) accomplish a similar intentional act, unlike the so-called canonical neurons, which respond only to presentation of the object. The functional role of mirror neurons is relevant to the gestural origin of language. According to several authors (e.g., Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2008 ), their primary function is related to an implicit and nonreflective understanding of manual actions: these neurons allow the subject to understand actions made by others through mapping those actions on acts that he or she is able to perform (Rizzolatti et al. 2001 ).

When highlighting the role of mirror neurons in manual action understanding, several scholars hypothesized that these neurons may have had a key role in a communication system based on hand gestures that paved the way to human language (e.g., Arbib 2005 ; Corballis 2010b ; Rizzolatti and Arbib 1998 ). One of the key elements of this hypothesis is that the F5 area of the ventral premotor cortex of the macaque is homologous to Broca’s area in humans, specifically to Broadman area 44 (Rizzolatti and Arbib 1998 ). In humans, this area is involved in general motor functions, such as the control of the complex hand movements (Binkofski and Buccino 2004 ), but it also plays a key role in some linguistic processes (e.g., Broca 1861 ; Embick et al. 2000 ; Fedorenko et al. 2012 ). As Broca’s area developed from a region originally involved in the processing of action, one could assume that the ability to recognize and perform manual actions provided the basis for developing the ability to perform and recognize communicative hand gestures that thereafter contributed to development of brain mechanisms that support spoken language (for a discussion, see Adornetti and Ferretti 2014 ). This provides an example of what has been called “neural reuse of action perception circuits for language” (for a review, see Pulvermüller 2018 ), the idea that mechanisms primarily carrying motor and sensory functions in animals (in our case, a system of manual action understanding) are altered and enhanced in humans to allow for their neural reuse in the service of linguistic or other higher cognitive functions (Anderson 2010 ).

This gesture-first account has been further corroborated by comparative data on monkey and ape communication that shows the existence of important differences between their vocal and gestural communicative signals. Although it is well known that nonhuman primates produce different acoustically vocal signals to communicate about different events or entities (e.g., Gouzoules et al. 1984 ; Seyfarth et al. 1980 ; Slocombe and Zuberbühler 2005 ), it is attested that gestural communication systems in these animals are more flexible than are vocal ones (Tomasello 2008 ). Moreover, neurophysiological investigations showed that nonhuman primates do not have the full neural equipment necessary for vocal control that would enable the production of novel sounds from the environment (Ploog 2002 ). The voluntary modulation, exaggeration, or inhibition of their calls can be viewed as an internal emotional state, such as the production of human emotional vocalizations (e.g., cry, laugh, scream; Meguerditchian and Vauclair 2014 ). Therefore, although the vocal mode of communication is often considered a precursor of speech (Burling 2005 ; MacNeilage 2008 ), animal vocal behavior alone does not seem to represent a starting point for the evolution of human communication.

Contrary to vocalizations, which are mostly instinctive expressions of emotions, nonhuman primate (especially apes) make manual gestures (i.e., visible movements of hands produced without using or touching objects) that can be voluntarily produced by the animal and used in a more flexible way than vocal signals. For example, apes can use gestures in different contexts to communicate different things (Pollick and de Waal 2007 ), such as modifying the behavior of a specific receiver (Roberts et al. 2013 ). Furthermore, when producing gestures, apes appraise the attentional state of the recipient: visual gestures (not accompanied by any sound) are frequently used when the receiver is paying attention to the indicator (Tomasello and Call 2007 ), while auditory and tactile gestures are produced to attract the attention of an individual who is not looking at the signaler (Tomasello et al. 1994 ). From this view, ape gestures and human language share a very important property: intentionality (for a discussion, see Roberts et al. 2013 ).

Nevertheless, the gesture-first theory of language origin is not without criticism. The most powerful argument against it is the so-called “modality transition problem” (Hewes 1973 ; Orzechowski et al. 2016 ). If language first emerged as a gestural–manual system, why should language have assumed the vocal-auditory form dominant today? This question is very relevant when considering that sign language—the communicative system used by people who are deaf—is as expressive as spoken language (Stokoe 1960 ). The gestural/manual system should have produced sign language as its natural consequence. In this respect, Wacewicz and Zywiczynski ( 2017 maintained that "the persistence of the problem, together with new sources of empirical data … was a powerful motivation for language evolution researchers to look to the multimodal alternatives whereby, from the start, the evolutionary emergence of language involved an intimate connection and interplay between the vocal-auditory and motor-visual modalities (e.g., Kendon 2011 ; McNeill 2012 ; Collins 2013 ; Sandler 2013 ; Zlatev 2014 )" (p. 4).

Some of the arguments supporting the multimodal scenario come from gesturology research, according to which both the organization of body movement and speech contribute to the process of languaging (Kendon 2004 ). The idea is that gesture and speech comprise a single multimodal system with gesture not as an ornament or accompaniment to speech but rather part of it (Goldin-Meadow 2003 ; McNeill 2012 ). Adhering to this view, Hostetter and Alibali ( 2008 ) highlighted that both gesture and speech rely on the same simulative processes. As described in the previous section, simulations are neural enactments or reenactments of interactions with the world. According to Hostetter and Alibali ( 2008 ), when a speaker engages in these reenactments, the same motor and perceptual cerebral areas are recruited that would be involved in physically performing or perceiving the scene. Forming a simulation evokes a motor plan that can be expressed alongside speech and gesture. Thus, gestures are a natural byproduct of the cognitive processes that underlie speaking; it is not possible to consider the two separately because both are expressions of the same simulation (Pouw and Hostetter 2016 ).

The multimodal theory of language evolution, the idea that bodily-visual and vocal-auditory signals were fully integrated at least from the beginning of language (e.g., McNeill 2012 ), is supported by recent comparative data. It has been shown that apes, especially chimpanzees, have a multimodal system of communication whereby the production of gestures is often associated with vocal signals and facial expressions (Liebal et al. 2013 ; Taglialatela et al. 2015 ). Furthermore, neurofunctional investigations have revealed that chimpanzees’ manual gesturing selectively activates their homologue to Broca’s area (Taglialatela et al. 2008 ) and that the pattern of activation is enhanced in subjects who simultaneously use both gestural and vocal signals (attention-getting calls; Taglialatela et al. 2011 ). These neurofunctional data support the “potential existence in chimpanzees of a multimodal intentional system that not only includes gestures but can also integrate, in some individuals, oro-facial and atypical vocal sounds” (Meguerditchian and Vauclair 2014 , p. 145).

These latter neurofunctional findings point to the question of connections between the mouth and the hand that may have played a role in the evolution of language. The mirror system (again) is relevant to explain these connections. Evidence attests that the monkey premotor cortex is involved in the production and perception of both oro-facial and forelimb actions: some neurons in F5 area activate when the monkey makes a movement to grasp an object with either the hand or mouth (Rizzolatti et al. 1988 ). Another category of mirror neurons, called “communicative mouth mirror neurons,” is activated by the observation of both mouth-communicative gestures (i.e., lip-smacking, lip protrusion, and tongue protrusion) carried out by the experimenter standing in front of the primate using motor actions associated with eating (Ferrari et al. 2003 ). Many investigations have attested this link in humans between hand and mouth (e.g., Gentilucci et al. 2001 ). For instance, Iverson and Thelen ( 1999 ) proposed that an association between the manual system and the vocal system is present from birth and paves the way for embodied language processing later in life. Pexman and Wellsby ( 2016 ) found a connection between children’s manual dexterity—the ability to make coordinated hand and finger movements to grasp and manipulate objects—and language skills. Based on the presence of a coupling between hand and mouth, Fogassi and Ferrari ( 2007 ) hypothesized that "the ventral premotor cortex, endowed with the control of both hand and mouth actions, could have played a pivotal role in associating gestures with vocalizations, thus producing new motor representations. At this stage, the mirror-neuron system, because of its capacity to match the seen/heard gesture or vocalization with internal motor representations, allowed the observer/listener to assign a meaning to these new vocal–gesture combinations" (p. 140).

It is important to highlight that both the gesture-first account and the multimodal perspective are compliant with the action-orient paradigm. In fact, in both cases, the core idea is that language is grounded in bodily sensory-motor systems; it is not a coincidence that both perspectives assign a crucial explicative role for the rise of language to mirror neurons. The difference between the two accounts lies in the degree of importance conferred to the vocal mode of expression. According to the gesture-first account, during the early stages of language evolution, vocalizations were simply an accompaniment to gesticulation, which unfold the primary communicative function. From the view of the multimodal perspective, vocalizations and gesticulation were functionally equivalent from the beginning, both being necessary for the whole communicative process.

To conclude, the study of the evolution of the expressive modality from an action-oriented perspective offers an illuminating example of how collecting and synthesizing data from a broad range of disciplines has been possible when examining, in a scientific and systematic way, a subject that is crucial for understanding the origins of linguistic communication.

4 Deep Link Between Action, Social Cognition and Language

So far, we have discussed how the contribution of the action-oriented model of language has shifted the emphasis on the role of gesture in the origin of human communication. In this section, we will consider further crucial implications of assuming such action-oriented model. After considering the idea that action contributes to the making of the communicative expressive system, we now turn our attention to a different but strictly connected topic: the possible role of the embodied perspective in the explanation of the processes of language comprehension and production. How do the embodied models raise the issue of the interpretative level of language? In this regard, a further aspect distinguishing the embodied models from the syntactic-centric models emerges. As is well known, models that are guided by UG focus on the sentence constituent structure. This generates as consequence an “internalist” perspective in which the study of language coincides with the analysis of the rules governing the combination of symbols in the construction of the sentence. On the contrary, the embodied models are characterized by a focus on the relation between language and the external reality, specifically on how language might be grounded in the world (in this respect, the reference to grasping as basic condition for the emergence of language is illustrative; see Rizzolatti and Arbib 1998 ). Namely, whereas the biolinguistic models of language addressed the interpretative processes with reference to the combinatorial aspect of relating sound and arbitrary referents, now the embodied models shift the focus to the issue of grounding.

From this point of view, providing a comprehensive explanation of language means providing an explanation of how linguistic expressions are linked to external reality, ultimately it means understanding what meaning itself really is—the so-called “grounding problem” (Harnad 1990 ). This problem relates to what Chomsky ( 1966 ) defined as “Descartes’ problem” or the creative aspect of language use: how linguistic expressions can be appropriate to circumstances not being caused by them. Even though Chomsky ( 1964 ) states that “a theory of language that neglects this ‘creative’ aspect is of only marginal interest” (pp. 7–8), he considers the problem of appropriateness an unsolvable mystery. Indeed, the Chomskyan perspective can offer indications about how symbols relate to each other within the linguistic system but cannot account for how concepts emerge and relate to entities outside the system (see for a discussion Ferretti and Adornetti 2014 ). Much of the mystery clearly depends on the priority assigned to the syntactic plan. The grounding problem demands a link between language and reality that the syntactic-centric theories—defining language with reference to abstract, amodal, and arbitrary symbols combined by syntactic rules—are not equipped to address. The incompatibility between syntax and grounding calls for an inversion of paradigm. Can the action-oriented perspective, emphasizing the priority of grounding, embody such an inversion of paradigm?

By identifying the roots of language in the interaction between agents and environment, the framework of embodiment offers an approach to solving the symbol grounding problem, starting from a deep focus on the role of context (see Sect. 2 ). This focus strongly reframes the definition of symbol , here viewed as a structural coupling between an agent’s sensorimotor activations and its environment (Vogt 2002 ). To this extent, the question of appropriateness to the context is seen as a general problem concerning appropriateness of action to the ecological environment. The embodied account solves this latter problem of producing contextually appropriate behaviors taking into account a brain organized in terms of goal-directed motor acts (Rizzolatti et al. 2000 ). As pointed out by Glenberg and Gallese ( 2012 ), appealing to the “neural re-use” hypothesis (see Sect. 3 ), “the brain takes advantage of the solution of one different problem, namely contextually appropriate action, to solve another difficult problem, namely contextually appropriate language” (p. 911). This represents a completely different approach compared to that offered by the biolinguistic paradigm. If the issue of creativity of language use remained a mystery within that paradigm, the embodied perspective places critical constraints on the construction of meaning, starting from the primary constraints endemic to effective action. Given these constraints, the model can provide an account of how meaning emerges within a deep coupling between agent and context. Specifically, meanings are viewed as grounded through simulation in concrete experiences.

One area where the embodied approach has provided a fruitful contribution to language grounding is that of lexicon. Such a contribution has been particularly fostered by the mirror system hypothesis (for a review, see Arbib et al. 2014 ). As we have shown in Sect. 3 , according to this hypothesis, the mechanisms that originally evolved for action control have been exploited for language processing (Glenberg and Gallese 2012 ). More specifically, a “mirror for actions” system—concerned with both generating an action appropriate to the object’s affordances and recognizing the action being performed by another individual—provided the evolutionary basis for the emergence of a “mirror for words and constructions” system. In this way, the mirror system allows for complex imitation to be transferred from manual skills to a new communicative domain. The link between action-perception circuits and merging of circuits into higher-order ones makes a direct association between meaning and motor acts on one side and between meaning and object representations on the other. The master role played by the interplay between action-supporting regions of the brain to the emergence of semantics (e.g., Pulvermüller et al. 2014 ) provides a bottom-up account of language that is grounded in sensory-motor representation.

So far so good. The embodied approach presents itself as an option alternative to the biolinguistic program. The shifting in perspective towards embodiment has shown that alternative models of language referring to properties very different from those considered by biolinguistics are possible. Providing an action-based model of cognition that founds linguistic information on the grounding of symbols through the agent’s interaction with the environment, the embodied account goes in the desirable direction of building a different model of language compared to UG. Moreover, as it suggests that the supposedly high processes might be reframed in terms of a constituent contribution provided by low processes intrinsically linked to the domain of action, the embodied account offers a model of language that has a strong evolutionary plausibility.

That said, when it comes to the definition of language provided within the embodied perspective, two difficulties emerge, both involving the issue of language origins. The first difficulty concerns the priority assigned to lexicon. In terms of the origins, approaches centered on the rule of atomic elements are the most intuitive, carried out by scholars such as Bickerton ( 1990 ). However, the lexical protolanguage models are also very problematic. As emphasized by Fitch ( 2010 ), they presuppose an infrastructure for speech founded on vocal imitation and a capacity for referential communication that are not well thematized in approaches of this kind, leaving important evolutionary problems open. The second difficulty regards the fact that, after emphasizing the importance of grounding, embodied approaches (unlike biolinguistics) cannot count on a model of language fortified by > 50 years of thinking. When called upon to deal with defining what they mean by language , in fact, several scholars relating to embodied cognition have offered a definition that, quite unexpected, coincides with that of Chomsky: Glenberg and Gallese ( 2012 , p. 910), for example, defined language as “a productive system in that a finite number of words and syntactic rules can be used to generate an infinite number of sentences.” The emphasis on syntax is further underlined by the agenda for the future proposed by the embodied perspective; that is, explaining a motor theory of syntax for truly a theory of language (Caruana and Borghi 2016 ). Clearly, that of bringing together biolinguistics and embodiment is a legitimate program. However, such an option incurs the risk of leading again to a model of language that undermines the strong distinctions existing between the two paradigms. An alternative option is that, starting from the centrality of grounding, the action-oriented perspective paves the way to a different model of language. Indeed, if embodiment identifies the issue of grounding as a central tenet of its proposal and acknowledges meaning as a function of language use more than language per se (Evans 2006 ), more than focusing on the combinatorial aspects of language, it is reasonable to turn attention to models of language that stress the notion of anchoring to the context. What direction to take to combine an action-oriented perspective with a model addressing the issue of language origins, starting from notions such as that of context? It is our claim that, as a result of its features, the embodied approach has deep similarities with a pragmatic-based model of language—centered on a definition of language in terms of use more than in terms of grammatical competence.

Such a theory stating that language should be explained with reference to a strong pragmatic notion of context is the ostensive–inferential model of communication (OIMC) or relevance theory (Sperber and Wilson 1986 / 1995 ). Starting from the well-known Gricean philosophical account of communication (Grice 1975 ), OIMC has been corroborated by cognitive data that attest to the plausibility of a communicative model centered on the role of context and intentionality (Scott-Phillips 2014 ; Sperber and Wilson 1986 / 1995 ). Within the OIMC the notion of intentional communication becomes a topic of central concern. Then how is the role of such notions framed within the OIMC? According to the model, a linguistic interaction is characterized by the speaker’s meaning, a complex communicative intention aimed to achieve a certain effect on the hearer’s mind by means of the hearer’s recognition of the intention to achieve this effect. In these terms, pragmatic interpretation is ultimately an exercise of mindreading, with speakers trying to use the right sort of evidence to allow the audience to determine a contextually appropriate interpretation of linguistic expressions. This way of interpreting communication broadens the perspective on the notion of context. Pragmatics is not just elaborating the contextually appropriate actions in a physical environment; it also means solving problems related to the social context. From this point of view, the social-cognitive infrastructure underlying engagement with other minds represents a major crux in the investigation of language as well as its origins and evolution (e.g., Dunbar 1998 ; Origgi and Sperber 2000 ; Scott-Phillips 2014 ; Tomasello 2008 ). In fact, the focus on the role of mindreading as a precondition for the phylogenetic development of language is at the heart of much current work (e.g., Scott-Phillips 2014 ; Origgi and Sperber 2000 ). In this regard, we do have a robust theory of language alternative to that proposed by the biolinguistic program and conforms to evolutionary theory that takes into account the pragmatic aspect of language.

Although there are no models available allowing us to explicitly deal with the relation between embodiment and OIMC, we have some interesting indications suggesting that such a kind of relation might be fruitfully considered the agenda for the future of both the embodied perspective and the OIMC. At least two considerations are in favor of this claim. First, such a relation might provide the action-oriented perspective with a robust model of language (as robust as the Chomskyan theory) considering that to date the major limitation of this perspective is exactly the lack of a model of this kind. Further, combining embodiment with OIMC might be also fruitful for the relevance account that, although reconsidering the pragmatic aspects related to context, at least at the level of cognitive architectures is deeply tied to classical computationalism. Given the importance assigned to it within OIMC, theory of mind might be an example in this respect. The embodied perspective allows to rethink important aspects of theory of mind starting from a different angle compared to the ostensive perspective. The metapsychological device considered within the relevance account as a high-level cognitive mechanism (Sperber and Wilson 2002 ) can be reframed in terms of the more basic system of mindreading. Such a shift in perspective is founded on the claim that perception–action systems are mechanisms devoted to regulating not just the intentional action control but also the shaping of social interactions (Gallese et al. 2002 ; Fusaroli et al. 2012 ). Neurocognitive literature has provided strong evidence in support of these intersubjective bases of embodied cognition (e.g., Galantucci and Sebanz 2009 ), showing that mirror neurons can serve a self-other matching function (e.g., Gallese 2009 ); they are involved in coupling observation and execution of goal-related motor actions responding both when an action is performed and when the same action, performed by another individual, is simply observed (Gallese and Goldman 1998 ). The idea that similar intercorporeal matching mechanisms ground our connectedness to others is related to their functional role, that is, embodied simulation or motor resonance. Embodied simulation implies the mutual resonance of intentionally sensory-motor behaviors. Neuroscientific evidence shows that it is mediated by the activation of the same brain regions underlying our own sensory experiences (Gallese et al. 2004 ). In this perspective, the association of observed behaviors with a reactivation of our own body states is a way to recognize and understand those behaviors according to motor vocabulary mapping actions and representations (Rizzolatti and Luppino 2001 ). This common motor vocabulary guarantees a degree of congruence between the action repertoires of different individuals, a similarity of brain schemas when they interact. The notion of embodied simulation based on the immediate understanding of other’s actions lies at the core of the so-called motor account of social cognition. From this account follows the idea that mirroring other people’s actions is a way to directly comprehend their minds (Blakemore and Decety 2001 ). Indeed, if observing other’s actions allows for interpreting them as if they were one’s own, then it is possible to infer what motivated those actions and the intentions of the actor who performed them (Goldman 2006 ).

To this extent, the motor account of social cognition could provide a suitable alternative hypothesis about the nature of mindreading and its resulting role in language origins and evolution. As the mirror system is implicated in capturing intentions via action simulation, mindreading could be considered as playing a putative role in the pragmatic function of inferring communicative intentions (Cosentino 2014 ). Thus, the basic sensory-motor system would represent the key to pragmatics, as it implements the mental simulation of others’ actions, giving rise to expectations that provide direct comprehension of intentions, regardless of the explicit attribution of propositional attitudes (Glenberg and Gallese 2012 ). This is a simulative theory of comprehension based on the claim that the sensory-motor system provides a brain that is not only a brain that acts , but it is first of all a brain that understands (Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2008 ). If perceiving and acting pass through comprehension, then the building of a we-centric space underpinned by embodied simulation (Gallese 2009 ) is a bridge to meaning. From an evolutionary point of view, these considerations are particularly relevant as they pave the way to the idea that embodiment has a crucial role in meaning-making processes within a social-situated interaction (Arbib and Rizzolatti 1997 ; Gilissen 2005 ; Tettamanti et al. 2005 ). Moreover, the metapsychological complex levels of mindreading involved in communication can be framed as readjustments of the early basic sensory-motor skills. The process of reading each other’s minds is driven by the same sequence schema representation active in both communicative partners, allowing them to predict and understand each other’s actions, giving rise to meaning. Meaning is considered as a context-bound phenomenon that emerges in the context of embodied social action.

Based on the considerations made in this paper, the effort to bring together embodied theory of cognition with a pragmatic approach to communication represents the most fruitful way to build a model of language that meets the conformity constraint. Rather than stressing the necessity to hold embodiment and syntax together, future challenges might concern working on the contact points between embodiment and the OIMC. This could represent a line of investigation that, along with the challenge of providing more solid explanations of how simulation is a constituent component of language processing, might provide a paradigm of interest for understanding how the intertwined dimension of action, perception, and intersubjectivity might be involved in language origins and evolution.

5 Present Issue

This special issue provides an interdisciplinary view on contemporary language evolution research. It opens with two articles, those of Nathalie Gontier and Francesco Suman, which address epistemological issues concerning the relation between theory of evolution and language origin research. Considering the theory of evolution as the starting point of the investigation (following what, in this article, we have called the “conformity constraint”), both papers show how the conceptual assumptions of the theory of evolution affect and can fruitfully inform the study of language phylogeny. Gontier suggests how an applied evolutionary epistemological approach can help evolutionary linguistics at individuating the units, levels, and mechanisms of language evolution. Suman shows, within the framework of the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis, how factors such as niche construction, inclusive inheritance, phenotypic plasticity, and developmental constraints are relevant for conceptualizing the evolution of language: all these factors highlight the crucial role of the relationship between organisms and their environment for the origin of linguistic abilities.

The analysis of the genetic and phenotypic preconditions underlying language evolution is also the focus of the contribution from Antonio Benítez-Burraco, Constantina Theofanopoulou, and Cedric Boeckx. The authors hypothesize that genetic changes that have led to globularization of the braincase, and the processes responsible for the emergence of the (self-)domestication in our species (the fact that humans share many of the typical characteristics of domesticated species, such as reduced skeletal and cranial robusticity, changes in dentition, retention of juvenile characteristics, etc.) are closely related phenomena, and both have contributed to the appearance of natural languages.

Andrea Parravicini and Telmo Pievani present three different and historically recurrent approaches to the evolution of language: “evolution-free discontinuity” (the early version of UG model), “gradual evolutionary continuity” (the compatibilist model of UG elaborated by Pinker and Bloom 1990 ), and “punctuationist evolutionary approach” (the minimalist version of UG). The two authors present the main concepts of these approaches and discuss the limitations of each.

Ian Tattersall reconstructs the origin of linguistic capacity within a paleoanthropological and archaeological framework, assuming UG as model of language. The author hypothesizes that the neural capacity for language was acquired with the emergence of Homo sapiens 200,000 years ago, but that this new potential was not exploited until about 100,000 years later, through processes of exaptation and emergence. In proposing this hypothesis, Tattersall adheres to the idea that was a single, short-term event that led to the rise of human language.

A different scenario is outlined by Michael Corballis in his contribution. The author advocates the idea that developmental changes that led to language probably took place gradually during the Pleistocene epoch, rather than as a sudden event in the evolution of Homo sapiens . The author examines both the evolution of the cognitive capacities underlying language and the unfolding of the communicative sensory modality. Concerning the first point, Corballis focuses on two specific properties of linguistic communication: generativity and the ability to understand the thoughts of others. He suggests that such properties have precursors in the cognitive capacities of nonhuman animals. Regarding the question of the evolution of the expressive code (in line with the action-oriented paradigm we have described in this paper) he proposes a gestural account in which a crucial role is assigned to pantomime.

The role of pantomime in language evolution is also the topic of the article by Przemysław Żywiczyński, Slawomir Wacewicz, and Marta Sibierska. The authors start from the observation that there is not a commonly accepted definition of “pantomime” in language evolution research, although many scholars have hypothesized a pantomimic stage in phylogenetic processes that have led to human communication. For this, after reviewing different areas of investigations (e.g., theatre studies, semiotics, neuroscience), they offer an expanded definition of pantomime , bringing out its nonconventional, motivated, and multimodal nature.

Another contribution that focuses on communicative sensory modality from an action-oriented perspective is that of Antonella Tramacere and Richard Moore. The authors deal with a specific issue characterizing the gestural theories: the relation between imitation, mirror neurons, and social learning. Relying on data coming from neuroscience, primatology, and archaeology, Tramacere and Moore suggest that while gestural communication played a crucial role in language evolution, the grounds for thinking that manual imitation also did are currently unconvincing.

Finally, the last two articles of the special issue adhere to a pragmatic model of language and address two important issues in this regard: the evolution of cooperative communication and the emergence of informative categories, such as topic and presupposition. Richard Moore analyses the evolutionary plausibility of Gricean cooperative model of communication. Against the idea that cooperative communication presupposes intentional action and abilities of joint action, the author advocates a bottom-up hypothesis according to which the abilities and motivations for joint and intentional action might be acquired through participation in communicative interaction. Based on the debate of the nature of protolanguage, Edoardo Lombardi Vallauri and Viviana Masia suggest that presuppositions and topics, which are entrusted to a form of automatic processing, might have been developed to improve language ergonomics by sparing processing effort on some utterance contents.

Adornetti I, Ferretti F (2014) The pragmatic foundations of communication: an action-oriented model of the origin of language. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum 11:63–80

Article Google Scholar

Anderson ML (2010) Neural reuse: a fundamental organizational principle of the brain. Behav Brain Sci 33:245–266

Arbib MA (2005) From monkey-like action recognition to human language: an evolutionary framework for neurolinguistics. Behav Brain Sci 28(2):105–124

Google Scholar

Arbib MA, Rizzolatti G (1997) Neural expectations: a possible evolutionary path from manual skills to language. Commun Cogn 29:393–423

Arbib MA, Liebal K, Pika S (2008) Primate vocalization, gesture, and the evolution of human language. Curr Anthropol 49(6):1053–1076

Arbib MA, Gasser B, Barrès V (2014) Language is handy but is it embodied? Neuropsychologia 55:57–70

Armstrong DF, Wilcox SE (2007) The gestural origin of language. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Book Google Scholar

Bak TH, O’Donovan DG, Xuereb JH, Boniface S, Hodges JR (2001) Selective impairment of verb processing associated with pathological changes in Brodmann areas 44 and 45 in the motor neuron disease–dementia–aphasia syndrome. Brain 124:103–120

Barrós-Loscertales A, González J, Pulvermüller F, Ventura-Campos N, Bustamante JC, Costumero V, Parcet MA, Avila C (2012) Reading salt activates gustatory brain regions: fMRI evidence for semantic grounding in a novel sensory modality. Cereb Cortex 22:2554–2563

Barsalou LW (1999) Perceptual symbol systems. Behav Brain Sci 22:577–660

Barsalou LW (2010) Grounded cognition: past, present, and future. Top Cogn Sci 2:716–724

Beer R (2014) Dynamical systems and embedded cognition. In: Frankish K, Ramsey WR (eds) The Cambridge handbook of artificial intelligence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Benítez-Burraco A, Boeckx C (2014) Universal grammar and biological variation: an EvoDevo agenda for comparative biolinguistics. Biol Theory 9(2):122–134

Berthoz A (1997) Le Sens du movement. Odile Jacob, Paris

Berwick RC, Chomsky N (2015) Why only us: language and evolution. MIT press, Cambridge

Bickerton T (1990) Language and species. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Bickerton D (2012) The origin of syntactic language. In: Tallerman M, Gibson K (eds) The Oxford handbook of language evolution. Oxford University Press, New York

Binkofski F, Buccino G (2004) Motor functions of the Broca’s region. Brain Lang 89(2):362–369

Blakemore SJ, Decety J (2001) From the perception of action to the understanding of intention. Nat Rev Neurosci 2(8):561

Boeckx C, Benitez-Burraco A (2014) Biolinguistics 2.0. In: Fujita K, Fukui N, Yusa N, Ike-Uchi M (eds) The design, development and evolution of human language: biolinguistics explorations. Kaitakusha, Tokyo

Broca P (1861) Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche du cerveau. Bull Soc Anthropol 2:235–238

Burling R (2005) The talking ape: how language evolved. Oxford University Press, New York

Cangelosi A (2012) Robotics and embodied agent modelling of the evolution of language. In: Tallerman M, Gibson K (eds) The Oxford handbook of language evolution. Oxford University Press, New York

Caruana F, Borghi A (2016) Il cervello in azione. Il Mulino, Bologna

Cattaneo Z, Devlin JT, Salvini F, Vecchi T, Silvanto J (2010) The causal role of category-specific neuronal representations in the left ventral premotor cortex (PMv) in semantic processing. NeuroImage 49:2728–2734

Chomsky N (1964) Current issues in linguistic theory. The Hague, Mouton

Chomsky N (1966) Cartesian linguistics: a chapter in the history of rationalist thought. Harper & Row, New York

Chomsky N (1995) The minimalist program. MIT Press, Cambridge

Chomsky N (2007) Biolinguistic explorations: design, development, evolution. Int J Philos Stud 15(1):1–21

Chomsky N (2010) Some simple evo devo theses: how true might they be for language? In: Larson R, Déprez V, Yamakido H (eds) The evolution of human language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Collins C (2013) Paleopoetics: the evolution of the literary imagination. Columbia University Press, New York

Corballis MC (2002) From hand to mouth: the origins of language. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Corballis MC (2010a) The gestural origins of language. WIREs Cogn Sci 1:2–7

Corballis MC (2010b) Mirror neurons and the evolution of language. Brain Lang 112(1):25–35

Corballis MC (2017) The truth about language: what it is and where it came from. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Cosentino E (2014) Embodied pragmatics and the evolution of language. HumanaMente J Philos Stud 27:61–78

Cosentino E, Baggio G, Kontinen J, Werning M (2017) The time-course of sentence meaning composition. N400 effects of the interaction between context-induced and lexically stored affordances. Front Psychol 8:(818)

Cotelli M, Borroni B, Manenti R, Zanetti M, Arévalo A, Cappa SF, Padovani A (2007) Action and object naming in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. Eur J Neurol 14:632–637

Dediu D, Levinson SC (2013) On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences. Front Psychol 4:397

Dediu D, Levinson SC (2018) Neanderthal language revisited: not only us. Curr Opin Behav Sci 21:49–55

Di Pellegrino G, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G (1992) Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Exp Brain Res 91(1):176–180