Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The Jewish Angel

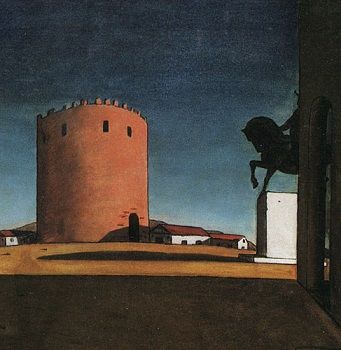

Giorgio de Chirico

Gala Éluard

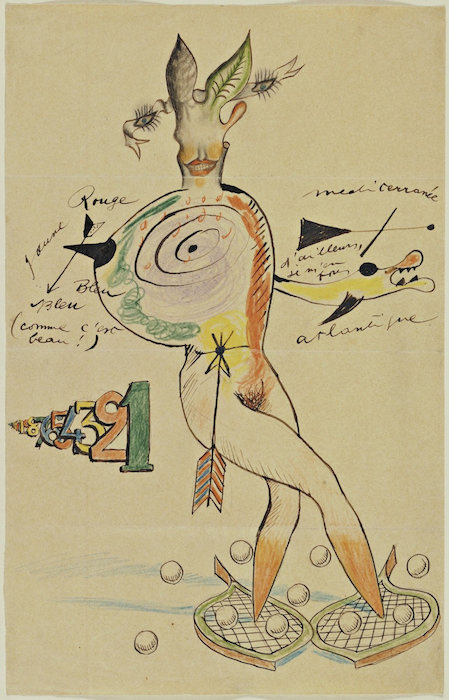

Photo: This Is the Color of My Dreams

Nude Standing by the Sea

Pablo Picasso

The Accommodations of Desire

Salvador Dalí

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box)

Marcel Duchamp

Hans Bellmer

The Barbarians

Self-Portrait

Leonora Carrington

The Satin Tuning Fork

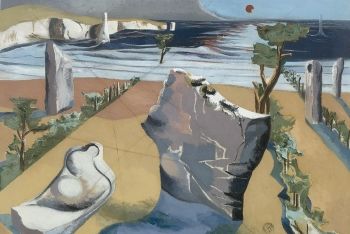

Yves Tanguy

Being With (Être Avec)

Roberto Matta

The Great Sirens

Paul Delvaux

The Eternally Obvious

René Magritte

James Voorhies Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

Surrealism originated in the late 1910s and early ’20s as a literary movement that experimented with a new mode of expression called automatic writing, or automatism, which sought to release the unbridled imagination of the subconscious. Officially consecrated in Paris in 1924 with the publication of the Manifesto of Surrealism by the poet and critic André Breton (1896–1966), Surrealism became an international intellectual and political movement. Breton, a trained psychiatrist, along with French poets Louis Aragon (1897–1982), Paul Éluard (1895–1952), and Philippe Soupault (1897–1990), were influenced by the psychological theories and dream studies of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) and the political ideas of Karl Marx (1818–1883). Using Freudian methods of free association, their poetry and prose drew upon the private world of the mind, traditionally restricted by reason and societal limitations, to produce surprising, unexpected imagery. The cerebral and irrational tenets of Surrealism find their ancestry in the clever and whimsical disregard for tradition fostered by Dadaism a decade earlier.

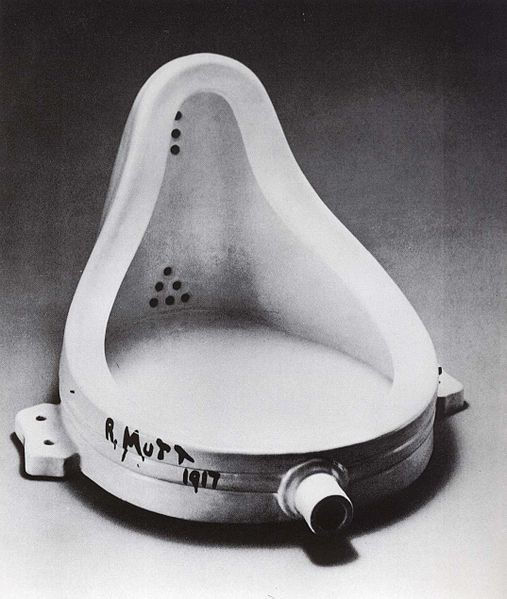

Surrealist poets were at first reluctant to align themselves with visual artists because they believed that the laborious processes of painting, drawing, and sculpting were at odds with the spontaneity of uninhibited expression. However, Breton and his followers did not altogether ignore visual art. They held high regard for artists such as Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Francis Picabia (1879–1953), and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) because of the analytic, provocative, and erotic qualities of their work. For example, Duchamp’s conceptually complex Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915–23; Philadelphia Museum of Art) was admired by Surrealists and is considered a precursor to the movement because of its bizarrely juxtaposed and erotically charged objects. In 1925, Breton substantiated his support for visual expression by reproducing the works of artists such as Picasso in the journal La Révolution Surréaliste and organizing exhibitions that prominently featured painting and drawing.

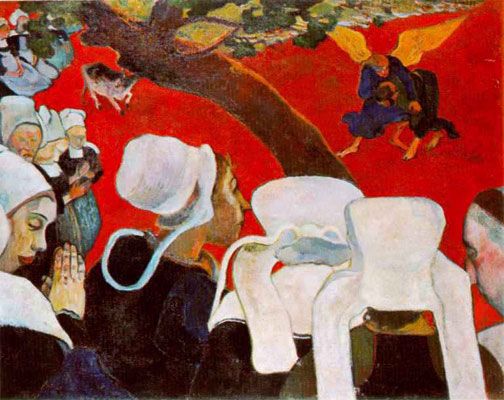

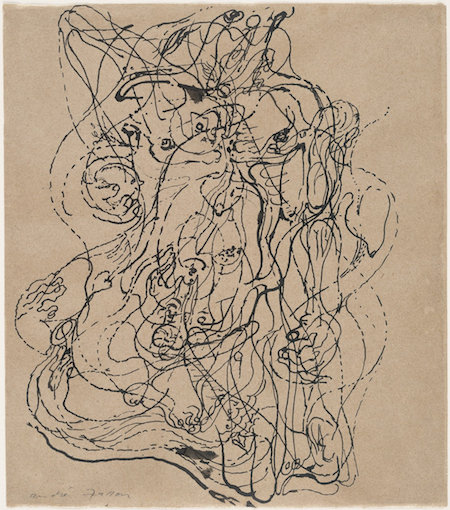

The visual artists who first worked with Surrealist techniques and imagery were the German Max Ernst (1891–1976), the Frenchman André Masson (1896–1987), the Spaniard Joan Miró (1893–1983), and the American Man Ray (1890–1976). Masson’s free-association drawings of 1924 are curving, continuous lines out of which emerge strange and symbolic figures that are products of an uninhibited mind. Breton considered Masson’s drawings akin to his automatism in poetry. Miró’s Potato ( 1999.363.50 ) of 1928 uses comparable organic forms and twisted lines to create an imaginative world of fantastic figures.

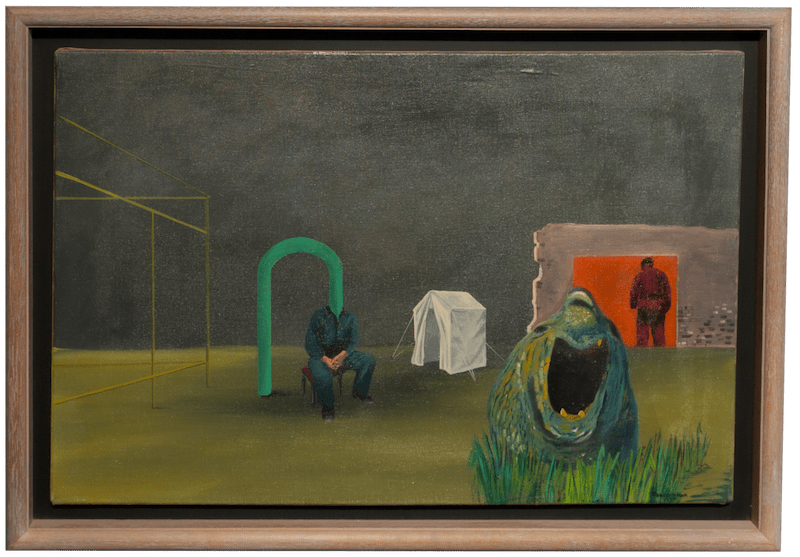

About 1937, Ernst, a former Dadaist, began to experiment with two unpredictable processes called decalcomania and grattage. Decalcomania is the technique of pressing a sheet of paper onto a painted surface and peeling it off again, while grattage is the process of scraping pigment across a canvas that is laid on top of a textured surface. Ernst used a combination of these techniques in The Barbarians ( 1999.363.21 ) of 1937, a composition of sparring anthropomorphic figures in a deserted postapocalyptic landscape that exemplifies the recurrent themes of violence and annihilation found in Surrealist art.

In 1927, the Belgian artist René Magritte (1898–1967) moved from Brussels to Paris and became a leading figure in the visual Surrealist movement. Influenced by de Chirico’s paintings between 1910 and 1920, Magritte painted erotically explicit objects juxtaposed in dreamlike surroundings. His work defined a split between the visual automatism fostered by Masson and Miró (and originally with words by Breton) and a new form of illusionistic Surrealism practiced by the Spaniard Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), the Belgian Paul Delvaux (1897–1994), and the French-American Yves Tanguy (1900–1955). In The Eternally Obvious ( 2002.456.12a–e ), Magritte’s artistic display of a dismembered female nude is emotionally shocking. In The Satin Tuning Fork ( 1999.363.80 ), Tanguy filled an illusionistic space with unidentifiable, yet sexually suggestive, objects rendered with great precision. The painting’s mysterious lighting, long shadows, deep receding space, and sense of loneliness also recall the ominous settings of de Chirico.

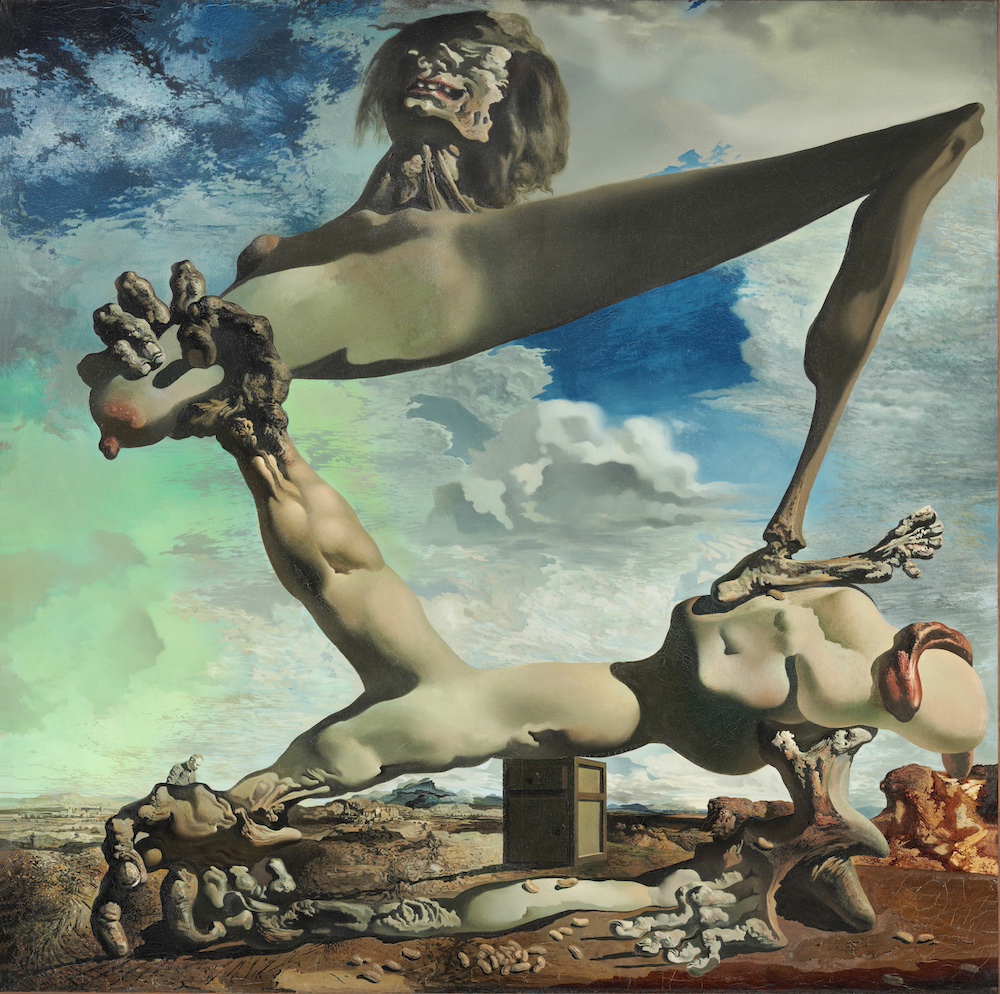

In 1929, Dalí moved from Spain to Paris and made his first Surrealist paintings. He expanded on Magritte’s dream imagery with his own erotically charged, hallucinatory visions. In The Accommodations of Desire ( 1999.363.16 ) of 1929, Dalí employed Freudian symbols, such as ants, to symbolize his overwhelming sexual desire. In 1930, Breton praised Dalí’s representations of the unconscious in the Second Manifesto of Surrealism . They became the main collaborators on the review Minotaure (1933–39), a primarily Surrealist-oriented publication founded in Paris.

The organized Surrealist movement in Europe dissolved with the onset of World War II. Breton, Dalí, Ernst, Masson, and others, including the Chilean artist Matta (1911–2002), who first joined the Surrealists in 1937, left Europe for New York. The movement found renewal in the United States at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery, Art of This Century, and the Julien Levy Gallery. In 1940, Breton organized the fourth International Surrealist Exhibition in Mexico City, which included the Mexicans Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) and Diego Rivera (1886–1957) (although neither artist officially joined the movement). Surrealism’s surprising imagery, deep symbolism, refined painting techniques, and disdain for convention influenced later generations of artists, including Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) and Arshile Gorky (1904–1948), the latter whose work formed a continuum between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism .

Voorhies, James. “Surrealism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/surr/hd_surr.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Ades, Dawn. Dada and Surrealism Reviewed . London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978.

Alexandrian, Sarane. Surrealist Art . New York: Thames & Hudson, 1985.

Brandon, Ruth. Surreal Lives: The Surrealists, 1917–1945 . London: Macmillan, 1999.

Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism . Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969.

Krauss, Rosalind E., and Jane Livingston. L'Amour Fou: Photography & Surrealism . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Abbeville, 1985.

Mundy, Jennifer, ed. Surrealism: Desire Unbound . Exhibition catalogue. London: Tate Publishing, 2001.

Rubin, William S. Dada and Surrealist Art . New York: Abrams, 1968.

Additional Essays by James Voorhies

- Voorhies, James. “ Europe and the Age of Exploration .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ School of Paris .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Elizabethan England .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Fontainebleau .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Post-Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004)

- New Vision Photography

- Photography and Surrealism

- Abstract Expressionism

- Design, 1900–1925

- Design, 1925–50

- Egyptian Modern Art

- Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) and Art

- Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986)

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- Photography at the Bauhaus

- Photography in the Expanded Field: Painting, Performance, and the Neo-Avant-Garde

- Photojournalism and the Picture Press in Germany

- The Structure of Photographic Metaphors

- Walker Evans (1903–1975)

- West Asia: Between Tradition and Modernity

- France, 1900 A.D.–present

- Germany and Switzerland, 1900 A.D.–present

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1900 A.D.–present

- Iberian Peninsula, 1900 A.D.–present

- Italian Peninsula, 1900 A.D.–present

- Low Countries, 1900 A.D.–present

- Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, 1900 A.D.–present

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 20th Century A.D.

- Abstract Art

- American Art

- Anthropomorphism

- Avant-Garde

- Biomorphism

- Expressionism

- Iberian Peninsula

- Literature / Poetry

- Mermaid / Merman

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Oil on Canvas

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Atget, Eugène

- Bellmer, Hans

- Carrington, Leonora

- Dalí, Salvador

- De Chirico, Giorgio

- Delvaux, Paul

- Duchamp, Marcel

- Freud, Lucian

- Gorky, Arshile

- Magritte, René

- Orozco, Jose Clemente

- Picabia, Francis

- Picasso, Pablo

- Rivera, Diego

- Tanguy, Yves

Summary of Surrealism

The Surrealists sought to channel the unconscious as a means to unlock the power of the imagination. Disdaining rationalism and literary realism, and powerfully influenced by psychoanalysis, the Surrealists believed the rational mind repressed the power of the imagination, weighing it down with taboos. Influenced also by Karl Marx , they hoped that the psyche had the power to reveal the contradictions in the everyday world and spur on revolution. Their emphasis on the power of personal imagination puts them in the tradition of Romanticism , but unlike their forebears, they believed that revelations could be found on the street and in everyday life. The Surrealist impulse to tap the unconscious mind, and their interests in myth and primitivism, went on to shape many later movements, and the style remains influential to this today.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- André Breton defined Surrealism as "psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express - verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner - the actual functioning of thought." What Breton is proposing is that artists bypass reason and rationality by accessing their unconscious mind. In practice, these techniques became known as automatism or automatic writing, which allowed artists to forgo conscious thought and embrace chance when creating art.

- The work of Sigmund Freud was profoundly influential for Surrealists, particularly his book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). Freud legitimized the importance of dreams and the unconscious as valid revelations of human emotion and desires; his exposure of the complex and repressed inner worlds of sexuality, desire, and violence provided a theoretical basis for much of Surrealism.

- Surrealist imagery is probably the most recognizable element of the movement, yet it is also the most elusive to categorize and define. Each artist relied on their own recurring motifs arisen through their dreams or/and unconscious mind. At its basic, the imagery is outlandish, perplexing, and even uncanny, as it is meant to jolt the viewer out of their comforting assumptions. Nature, however, is the most frequent imagery: Max Ernst was obsessed with birds and had a bird alter ego, Salvador Dalí's works often include ants or eggs, and Joan Miró relied strongly on vague biomorphic imagery.

Key Artists

Overview of Surrealism

Building upon the anti-rationalism of Dada, the Surrealists made powerful art and offered a new direction for exploration, as Max Ernst said: "creativity is that marvelous capacity to grasp mutually distinct realities and draw a spark from their juxtaposition."

Artworks and Artists of Surrealism

Carnival of Harlequin (1924-25)

Artist: Joan Miró

Miró created elaborate, fantastical spaces in his paintings that are an excellent example of Surrealism in their reliance on dream-like imagery and their use of biomorphism. Biomorphic shapes are those that resemble organic beings but that are hard to identify as any specific thing; the shapes seem to self-generate, morph, and dance on the canvas. While there is the suggestion of a believable three-dimensional space in Carnaval d'Arlequin , the playful shapes are arranged with an all-over quality that is common to many of Miró's works during his Surrealist period, and that would eventually lead him to further abstraction. Miró was especially known for his use of automatic writing techniques in the creation of his works, particularly doodling or automatic drawing, which is how he began many of his canvases. He is best known for his works such as this that depict chaotic yet lighthearted interior scenes, taking his influence from Dutch 17 th -century interiors.

Oil on canvas - Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

The Human Condition (1933)

Artist: René Magritte

The iconic and enigmatic René Magritte's works tend to be intellectual, often dealing with visual puns and the relation between the representation of something and the thing itself. In The Human Condition a canvas sits on an easel before a curtained window and reproduces exactly the scene outside the window that would be behind the canvas, thus the image on the easel in a sense becomes the scene, not just a reproduction of the landscape. There is in effect no difference between the two as both are fabrications of the artist. The hyperrealist painting style often used by Surrealists makes the odd setup seem dreamlike.

Oil on canvas - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Mama, Papa is Wounded! (1927)

Artist: Yves Tanguy

The most pivotal moment for Tanguy in his decision to become a painter was his sighting of a canvas by Giorgio de Chirico in a shop window in 1923. The next year, Tanguy, the poet Jacques Prévert, and the actor and screenwriter Marcel Duhamel moved into a house that was to become a gathering place for the Surrealists, a movement he became interested in after reading the periodical La Révolution surréaliste . André Breton welcomed him into the group in 1925. Tanguy was inspired by the biomorphic forms of Jean Arp, Ernst, and Miró, quickly developing his own vocabulary of amoeba-like shapes that populate arid, mysterious settings, no doubt influenced by his youthful travels to Argentina, Brazil, and Tunisia. Despite his lack of formal training, Tanguy's mature style emerged by 1927, characterized by deserted landscapes littered with fantastical rocklike objects painted with a precise illusionism. The works usually have an overcast sky with a view thatseems to stretch endlessly. Mama, Papa is Wounded depicts Tanguy's most common subject matter of war. The work is painted in a hyperrealist style with his distinctive limited color palette, both of which create a sense of dream-like reality. Tanguy often found the titles of works while looking through psychiatric case histories for compelling statements by patients. Given that, it is difficult to know if this work is relevant to his own family history as he claimed to have imagined the painting in its entirety before he began it. His brother was killed in World War I and the bleakness of the landscape may refer generally to losses suffered in the war by thousands of French families. De Chirico's influence on Tanguy's work is obvious here in his use of falling shadows and a classical torso in the landscape.

Oil on Canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Accommodations of Desire (1929)

Artist: Salvador Dalí

Painted in the summer of 1929 just after Dalí went to Paris for his first Surrealist exhibition, The Accommodations of Desire is a prime example of Dalí's ability to render his vivid and bizarre dreams with seemingly journalistic accuracy. He developed the paranoid-critical method, which involved systematic irrational thought and self-induced paranoia as a way to access his unconscious. He referred to the resulting works as "hand-painted dream photographs" because of their realism coupled with their eerie dream quality. The narrative of this work stems from Dalí's anxieties over his affair with Gala Eluard, wife of artist Paul Eluard. The lumpish white "pebbles" depict his insecurities about his future with Gala, circling around the concepts of terror and decay. While The Accommodations of Desire is an exposé of Dalí's deepest fears, it combines his typical hyper-realistic painting style with more experimental collage techniques. The lion heads are glued onto the canvas, and are believed to have been cut from a children's book.

Oil and cut-and-pasted printed paper on canvas - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Palace at 4 a.m. (1932)

Artist: Alberto Giacometti

Giacometti was one of the few Surrealists who focused on sculpture. The Palace at 4 a.m. is a delicate construction that was inspired by his obsession with a lover named Denise the previous year. Of the affair he said, "a period of six months passed in the presence of a woman who, concentrating all life in herself, transported my every moment into a state of enchantment. We constructed a fantastical palace in the night - a very fragile palace of matches. At the least false movement a whole section would collapse. We always began it again." In 1933, he told Breton that he was incapable of making anything that did not have something to do with her. The work includes representations or symbols of his love interest as well as perhaps of his mother. Other imagery, such as the bird, is less easy to interpret. Thus, the work is characterized by its bizarre juxtaposition of objects and a title that is seemingly unrelated to the constructed scene, giving the piece an undercurrent of mystery and tension as if something frightening is about to occur. The work, in its child-like simplicity, captures the fragility of memory and desire. Giacometti's postwar interest in Existentialism is already evident here in how he represents the isolation of the various figures.

Wood, glass, wire, and string - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Battle of Fishes (1926)

Artist: André Masson

Masson was one of the most enthusiastic followers of Breton's automatic writing, having begun his own independent experiments in the early 1920s. He would often produce art under exacting conditions, using drugs, going without sleep, or sustenance in order to relax conscious control of his art making so that he could access his unconscious. Masson, along with his neighbors Joan Miró, Antonin Artuad, and others would sometimes experiment together. He is best known for his use of sand. In an effort to introduce chance into his works, he would throw glue or gesso onto a canvas and then sand. His oil paintings were made based on the resulting shapes. Battle of the Fishes perhaps references his experiences in WWI. He signed up to fight and after three years, was seriously injured, taking months to recover in an army hospital and spending time in a psychiatric facility. He was unable for many years to speak of the things he witnessed as a soldier, but his art consistently depicts massacres, bizarre confrontations, rape, and dismemberment. Masson himself observed that male figures in his art rarely escape unharmed. Battle of Fishes has subdued color, but the fish seem involved in a vicious battle to the death with their razor-like teeth and spilled blood. Masson believed that the use of chance in art would reveal the sadism of all creatures - an idea that he could only reveal in his art.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Object (1936)

Artist: Meret Oppenheim

Oppenheim was one of the few women Surrealists whose work was exhibited with the group. Like Giacometti she worked primarily with objects. This work, also known under the title Luncheon in Fur , with its unsettling juxtaposition of a domestic object and animality, is a quintessential example of Surrealist ideas. The artist makes strange a teacup, saucer, and spoon purchased at typical department store - objects that were familiar are made disturbingly off-putting as the viewer must imagine drinking tea from a fur-covered cup.

Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Barbarians (1937)

Artist: Max Ernst

Max Ernst was known for his automatic writing techniques including frottage, grattage, and collage. Here he uses grattage, which requires taking a painted canvas, placing it on a textured surface, and scraping off paint. The method introduces elements of chance and unpredictability to the work as the artist is forced to release some control of the creative process. The grattaged canvas was then used by Ernst as inspiration for further imagery. The Barbarians is typically Surrealist as it is fraught with bizarre juxtapositions, mysterious figures, and dream-inspired symbols. The bird imagery is one of the staples of Ernst's work - he experienced a childhood trauma related to the death of his pet bird and as an adult developed a bird alter ego named Loplop.

Oil on wood with painted wood elements - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Mannequin (1938)

Artist: Man Ray

Mannequin depicts André Masson's mannequin at the Exposition International du Surrealisme, Galerie des Beaux-Arts, in Paris 1938. Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Maurice Henry, and others also designed these weird mannequins to fill a room with uncanny female forms that looked both monstrous and sexually alluring. Man Ray photographed them all as discreet characters, of which this is one example. He repeatedly photographed his assistant, artist Lee Miller, and many other women, both living and inanimate. Like Hans Bellmer, an artist peripherally associated with the group, Ray was obsessed with the female form as the perfect embodiment of male desire, and sought to capture it formally in fantastical ways. Man Ray also pioneered many photographic techniques, including rayographs , named after himself, that incorporate elements of chance and in which subjects appear to glow in dream-like silver auras.

Assemblage of wood, oil, metal, board on board, with artist's frame - National Gallery of Australia

Birthday (1942)

Artist: Dorothea Tanning

Birthday is a self-portrait that Dorothea Tanning painted to commemorate her 30th birthday. Viewed up close, one notices the infinite rooms recessing into the background, symbolizing Tanning's unconscious mind. Many Surrealists felt architectural imagery was well-suited to expressing notions of a labyrinthine self that changes and expands over time; Birthday is one of the best examples of this. Also notable is the gargoyle at the subject's feet. Tanning said this was her rendition of a lemur, which has been associated with death spirits. Tanning juxtaposed natural imagery, like the skirt made of roots, against objects representing high culture, like fancy apparel and interior design, to pay homage to culture as well as to express nature and wilderness as a feminine construct.

Oil on canvas - The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Beginnings of Surrealism

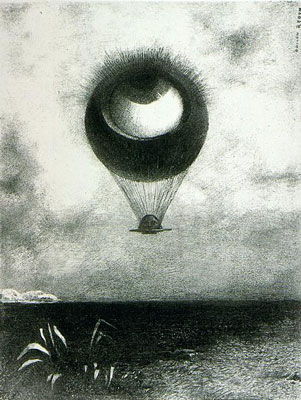

Surrealism grew out of the Dada movement, which was also in rebellion against middle-class complacency. Artistic influences, however, came from many different sources. The most immediate influence for several of the Surrealists was Giorgio de Chirico , their contemporary who, like them, used bizarre imagery with unsettling juxtapositions (and his Metaphysical Painting movement). They were also drawn to artists from the recent past who were interested in primitivism, the naive, or fantastical imagery, such as Gustave Moreau , Arnold Bocklin , Odilon Redon , and Henri Rousseau . Even artists from as far back as the Renaissance , such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo and Hieronymous Bosch , provided inspiration in so far as these artists were not overly concerned with aesthetic issues involving line and color, but instead felt compelled to create what Surrealists thought of as the "real."

The Surrealist movement began as a literary group strongly allied to Dada , emerging in the wake of the collapse of Dada in Paris, when André Breton's eagerness to bring purpose to Dada clashed with Tristan Tzara's anti-authoritarianism. Breton, who is occasionally described as the 'Pope' of Surrealism, officially founded the movement in 1924 when he wrote "The Surrealist Manifesto." However, the term "surrealism," was first coined in 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire when he used it in program notes for the ballet Parade , written by Pablo Picasso , Leonide Massine, Jean Cocteau , and Erik Satie.

Around the same time that Breton published his inaugural manifesto, the group began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste , which was largely focused on writing, but also included art reproductions by artists such as de Chirico, Ernst, André Masson, and Man Ray. Publication continued until 1929.

The Bureau for Surrealist Research or Centrale Surréaliste was also established in Paris in 1924. This was a loosely affiliated group of writers and artists who met and conducted interviews to "gather all the information possible related to forms that might express the unconscious activity of the mind." Headed by Breton, the Bureau created a dual archive: one that collected dream imagery and one that collected material related to social life. At least two people manned the office each day - one to greet visitors and the other to write down the observations and comments of the visitors that then became part of the archive. In January of 1925, the Bureau officially published its revolutionary intent that was signed by 27 people, including Breton, Ernst, and Masson.

Surrealism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Surrealism shared much of the anti-rationalism of Dada, the movement out of which it grew. The original Parisian Surrealists used art as a reprieve from violent political situations and to address the unease they felt about the world's uncertainties. By employing fantasy and dream imagery, artists generated creative works in a variety of media that exposed their inner minds in eccentric, symbolic ways, uncovering anxieties and treating them analytically through visual means.

Surrealist Paintings

There were two styles or methods that distinguished Surrealist painting. Artists such as Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte painted in a hyper-realistic style in which objects were depicted in crisp detail and with the illusion of three-dimensionality, emphasizing their dream-like quality. The color in these works was often either saturated (Dalí) or monochromatic (Tanguy), both choices conveying a dream state.

Several Surrealists also relied heavily on automatism or automatic writing as a way to tap into the unconscious mind. Artists such as Joan Miró and Max Ernst used various techniques to create unlikely and often outlandish imagery including collage , doodling, frottage, decalcomania, and grattage. Artists such as Hans Arp also created collages as stand-alone works.

Hyperrealism and automatism were not mutually exclusive. Miro, for example, often used both methods in one work. In either case, however the subject matter was arrived at or depicted, it was always bizarre - meant to disturb and baffle.

Surrealist Objects and Sculptures

Breton felt that the object had been in a state of crisis since the early-19 th century and thought this impasse could be overcome if the object in all its strangeness could be seen as if for the first time. The strategy was not to make Surreal objects for the sake of shocking the middle class a la Dada but to make objects "surreal" by what he called dépayesment or estrangement. The goal was the displacement of the object, removing it from its expected context, "defamilarizing" it. Once the object was removed from its normal circumstances, it could be seen without the mask of its cultural context. These incongruous combinations of objects were also thought to reveal the fraught sexual and psychological forces hidden beneath the surface of reality.

A limited number of Surrealists are known for their three-dimensional work. Arp, who began as part of the Dada movement, was known for his biomorphic objects. Oppenheim's pieces were bizarre combinations that removed familiar objects from their everyday context, while Giacometti's were more traditional sculptural forms, many of which were human-insect hybrid figures. Dalí, less known for his 3D work, did produce some interesting installations, particularly, Rainy Taxi (1938), which was an automobile with mannequins and a series of pipes that created "rain" in the car's interior.

Surrealist Photography

Photography, because of the ease with which it allowed artists to produce uncanny imagery, occupied a central role in Surrealism. Artists such as Man Ray and Maurice Tabard used the medium to explore automatic writing, using techniques such as double exposure, combination printing, montage, and solarization, the latter of which eschewed the camera altogether. Other photographers used rotation or distortion to render bizarre images.

The Surrealists also appreciated the prosaic photograph removed from its mundane context and seen through the lens of Surrealist sensibility. Vernacular snapshots, police photographs, movie stills, and documentary photographs all were published in Surrealist journals like La Révolution surréaliste and Minotaure , totally disconnected from their original purposes. The Surrealists, for example, were enthusiastic about Eugène Atget's photographs of Paris. Published in 1926 in La Révolution surréaliste at the prompting of his neighbor, Man Ray, Atget's imagery of a quickly vanishing Paris was understood as impulsive visions. Atget's photographs of empty streets and shop windows recalled the Surrealist's own vision of Paris as a "dream capital."

Surrealist Film

Surrealism was the first artistic movement to experiment with cinema in part because it offered more opportunity than theatre to create the bizarre or the unreal. The first film characterized as Surrealist was the 1924 Entr'acte , a 22-minute, silent film, written by Rene Clair and Francis Picabia , and directed by Clair. But, the most famous Surrealist filmmaker was of course Luis Buñuel . Working with Dalí, Buñuel made the classic films Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L'Age d'Or (1930), both of which were characterized by narrative disjunction and their peculiar, sometimes disturbing imagery. In the 1930s Joseph Cornell produced surrealist films in the United States, such as Rose Hobart (1936). Salvador Dalí designed a dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945).

The Rise and Decline of Surrealism

Though Surrealism originated in France, strains of it can be identified in art throughout the world. Particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, many artists were swept into its orbit as increasing political upheaval and a second global war encouraged fears that human civilization was in a state of crisis and collapse. The emigration of many Surrealists to the Americas during WWII spread their ideas further. Following the war, however, the group's ideas were challenged by the rise of Existentialism , which, while also celebrating individualism, was more rationally based than Surrealism. In the arts, the Abstract Expressionists incorporated Surrealist ideas and usurped their dominance by pioneering new techniques for representing the unconscious. Breton became increasingly interested in revolutionary political activism as the movement's primary goal. The result was the dispersal of the original movement into smaller factions of artists. The Bretonians, such as Roberto Matta , believed that art was inherently political. Others, like Yves Tanguy, Max Ernst, and Dorothea Tanning, remained in America to separate from Breton. Salvador Dalí, likewise, retreated to Spain, believing in the centrality of the individual in art.

Later Developments - After Surrealism

Abstract expressionism.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art in New York staged an exhibition entitled Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism , and many American artists were powerfully impressed by it. Some, such as Jackson Pollock , began to experiment with automatism, and with imagery that seemed to derive from the unconscious - experiments which would later lead to his "drip" paintings. Robert Motherwell , similarly, is said to have been "stuck between the two worlds" of abstraction and automatism.

Largely because of political upheaval in Europe, New York rather than Paris became the emergent center of a new vanguard, one that favored tapping the unconscious through abstraction as opposed to the "hand-painted dreams" of Salvador Dalí. Peggy Guggenheim's 1942 exhibition of Surrealist-influenced artists (Rothko, Gottlieb, Motherwell, Baziotes, Hoffman, Still, and Pollock) alongside European artists Miró, Klee, and Masson, underscores the speed with which Surrealist concepts spread through the New York art community.

Feminism and Women Surrealists

The Surrealists have often been depicted as a tightly knit group of men, and their art often envisioned women as wild "others" to the cultured, rational world. Work by feminist art historians has since corrected this impression, not only highlighting the number of women Surrealists who were active in the group, particularly in the 1930s, but also analyzing the gender stereotypes at work in much Surrealist art. Feminist art critics, such as Dawn Ades, Mary Ann Caws, and Whitney Chadwick, have devoted several books and exhibitions to this subject.

While most of the male Surrealists, especially Man Ray, Magritte, and Dalí, repeatedly focused on and/or distorted the female form and depicted women as muses, much in the way that male artists had for centuries, female Surrealists such as Claude Cahun , Lee Miller , Leonora Carrington , and Dorothea Tanning , sought to address the problematic adoption of Freudian psychoanalysis that often cast women as monstrous and lesser. Thus, many female Surrealists experimented with cross-dressing and depicted themselves as animals or mythic creatures.

British Surrealism

Interestingly, many notable female Surrealists were British. Examples include Eileen Agar , Ithell Colquhoun , Edith Rimmington , and Emmy Bridgwater . Particular to the British interpretation of Surrealist ideology was an ongoing exploration of human relations with their surrounding natural environment and most prominently, with the sea. Alongside Agar, Paul Nash developed an interest in the object trouvé , usually in the form of items collected from the beach. The focus on the border where land meets the sea, and where rocks anthropomorphically resemble people struck a cord with British identity and more generally, with Surrealist principles of reconciling and uniting opposites.

The International Surrealist Exhibition (1936) held in London was a particular catalyst for many British artists. Headed by Roland Penrose and Herbert Read, the movement thrived in Britain, creating the international icons Leonora Carrington and Lee Miller , and also spurring on the practice of another important circle of artists surrounding Ben Nicholson , Barbara Hepworth , and Henry Moore . Overall, the privileging of an eccentric imagination and essential rejection of standardized and rational modes of doing things resonated well from the outset. This golden period for art in general in the UK, and more specifically the legacies of British Surrealism continue to influence the country’s art practice today.

Useful Resources on Surrealism

- The Art Story Blog: Dalí and The Surrealists - Master Marketers Top 10 marketing stunts by Tristan Tzara, Andre Breton, and Salvador Dalí

- The Art Story Blog: Leonora Carrington’s Surrealist Scenes Find Muse in Hieronymus Bosch's Christian Fantasies Carrington borrow's her Surrealist ideas from the 16 th -century artist

- The Art Story Blog: Leonora Carrington in Pop Culture Madonna and W Magazine fashion shoots based on Carrington's visions

- Surrealism (2010) By Mary Ann Caws

- Surrealism: Desire Unbound (2005) By Jennifer Mundy, Dawn Ades, and Vincent Gille

- Surrealism: Themes and Movements (2004) Our Pick By Mary Ann Caws

- Surrealist Women : An International Anthology (1998) By Penelope Rosemont

- André Breton's Manifestos of Surrealism By André Breton, Richard Seaver, Helen R. Lane

- History of the Surrealist Movement Our Pick By Gerard Durozoi

- Nadja (1928) Our Pick By Andre Breton

- A Book of Surrealist Games (1995) By Alastair Brotchie and Mel Gooding

- Surrealism (Basic Art Series 2.0, 2015) By Cathrin Klingsöhr-Leroy

- The Surrealism Reader: An Anthology of Ideas (2016) By Dawn Ades, Michael Richardson, and Krzysztof Fijalkowski

- Leonora Carrington Rewrote the Surrealist Narrative for Women By Anwen Crawford / The New Yorker / May 2017

- Dalí in a diving helmet: How the Spaniard almost suffocated bringing Surrealism to Britain Our Pick By Joanna Moorhead / The Guardian / June 2016

- From Dada to Surrealism - Review Our Pick By Phillippe Dagen / The Guardian / July 19, 2011

- Surrealist America By Lewis Kachur / Artnet Magazine / July 21, 2005

- ART REVIEW; In Old Age, Surrealism Still Charms By William Zimmer / The New York Times / February 4, 2004

- Surrealism For Sale, Straight From The Source; André Breton's Collection Is Readied for Auction Our Pick By Alan Riding / The New York Times / December 7, 2002

- ART/ARCHITECTURE; An Early Surrealist on His Own Revolutionary Terms By Ken Shulman / The New York Times / March 24, 2002

- ART REVIEW; Trolling the Mind's Nooks and Crannies for Images Our Pick By Grace Glueck / The New York Times / June 4, 1999

- Man Ray's films on Ubuweb Our Pick

- René Clair's Entr'act, a film written by Francis Picabia and Erik Satie

- Photomontage of Claude Cahun's self portraits

- Surrealist Movement in the U.S. Contemporary Surrealist Movement Information Site

- Surrealism Today Blog Dedicated to contemporary Surrealism in its many manifestations

Similar Art

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity (1882)

Vision After the Sermon (1888)

Fountain (1917)

Bidibidobidiboo (1996)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by The Art Story Contributors

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

Surrealism, an introduction

Reshaping the world.

When you think of maps, what comes to mind? An informative document used by travelers? Demarcations of national borders and geographic features? At the very least, we might think of some factual representation of the world, not one that is fictitious or subjective.

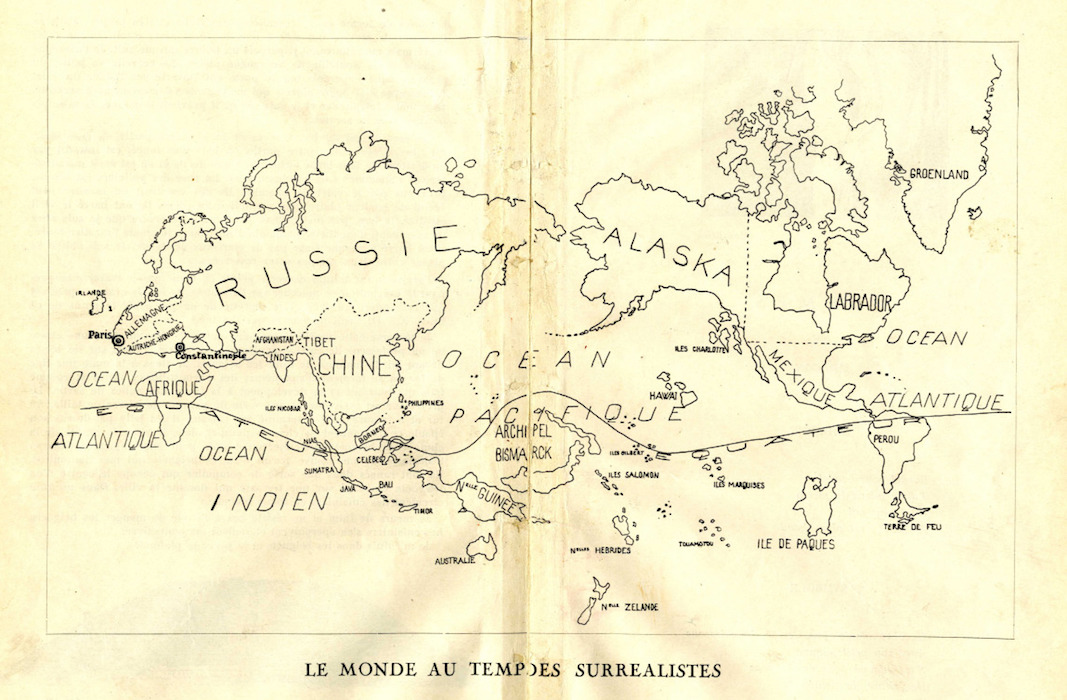

Imagine a map of the world. Now take a moment to examine the following map, created by members of the Surrealist movement and published in the Belgian journal Variétés in June 1929.

Le monde au temps des Surrealistes (The World at the Time of the Surrealists) , image from p. 26-27 in special issue “Le Surrealisme en 1929″ of Varietes: Revue mensuelle Illustree de l’espirit contemporain (June 1929)

This anonymous map might seem unsettling; it emphasizes certain areas while removing others, and changes dramatically the size of landmasses. How is this map different from the world we know? And, although it might seem like an odd place to begin, what can it tell us about the ideas and approaches of the Surrealists?

Marcel Jean, Spector of the Gardenia, 1936, plaster head, painted black cloth, zippers, film, velvet-covered wood base (MoMA)

Psychic freedom

Historians typically introduce Surrealism as an offshoot of Dada . In the early 1920s, writers such as André Breton and Louis Aragon became involved with Parisian Dada. Although they shared the group’s interest in anarchy and revolution, they felt Dada lacked clear direction for political action. So in late 1922, this growing group of radicals left Dada, and began looking to the mind as a source of social liberation. Influenced by French psychology and the work of Sigmund Freud, they experimented with practices that allowed them to explore subconscious thought and identity and bypass restrictions placed on people by social convention. For example, societal norms mandate that suddenly screaming expletives at a group of strangers—unprovoked, is completely unacceptable.

Man Ray, Recording a waking dream seance session, Bureau of Surrealist Research, c. 1924

Surrealist practices included “waking dream” seances and automatism. During waking dream seances, group members placed themselves into a trance state and recited visions and poetic passages with an immediacy that denied any fakery. (The Surrealists insisted theirs was a scientific pursuit, and not like similar techniques used by Spiritualists claiming to communicate with the dead.) The waking dream sessions allowed members to say and do things unburdened by societal expectations; however, this practice ended abruptly when one of the “dreamers” attempted to stab another group member with a kitchen knife. Automatic writing allowed highly trained poets to circumvent their own training, and create raw, fresh poetry. They used this technique to compose poems without forethought, and it resulted in beautiful and startling passages the writers would not have consciously conceived.

Envisioning Surrealism: automatic drawing and the exquisite corpse

In the autumn of 1924, Surrealism was announced to the public through the publication of André Breton’s first “Manifesto of Surrealism,” the founding of a journal ( La Révolution surréaliste ), and the formation of a Bureau of Surrealist Research. The literary focus of the movement soon expanded when Max Ernst and other visual artists joined and began applying Surrealist ideas to their work. These artists drew on many stylistic sources including scientific journals, found objects, mass media, and non-western visual traditions. (Early Surrealist exhibitions tended to pair an artist’s work with non-Western art objects). They also found inspiration in automatism and other activities designed to circumvent conscious intention.

André Masson, Automatic Drawing , 1924, ink on paper, 23.5 x 20.6 cm (MoMA)

Surrealist artist André Masson began creating automatic drawings , essentially applying the same unfettered, unplanned process used by Surrealist writers, but to create visual images. In Automatic Drawing (left), the hands, torsos, and genitalia seen within the mass of swirling lines suggest that, as the artist dives deeper into his own subconscious, recognizable forms appear on the page.

Another technique, the exquisite corpse , developed from a writing game the Surrealists created. First, a piece of paper is folded as many times as there are players. Each player takes one side of the folded sheet and, starting from the top, draws the head of a body, continuing the lines at the bottom of their fold to the other side of the fold, then handing that blank folded side to the next person to continue drawing the figure. Once everyone has drawn her or his “part” of the body, the last person unfolds the sheet to reveal a strange composite creature, made of unrelated forms that are now merged. A Surrealist Frankenstein’s monster, of sorts.

Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Max Morise, and Man Ray, Untitled (Exquisite Corpse) , 1926-27, colored pencil, pencil, and ink on paper, 35.9 x 22.9 cm (MoMA)

Whereas automatic drawing often results in vague images emerging from a chaotic background of lines and shapes, exquisite corpse drawings show precisely rendered objects juxtaposed with others, often in strange combinations. These two distinct “styles,” represent two contrasting approaches characteristic of Surrealists art, and exemplified in the early work of Yves Tanguy and René Magritte.

Left: Yves Tanguy, Apparitions , 1927, oil on canvas, 92.07 x 73.02 cm (Dallas Museum of Art); right: René Magritte, The Central Story , 1928, oil on canvas (Private collection)

Tanguy began his painting Apparitions (left) using an automatic technique to apply unplanned areas of color. He then methodically clarified forms by defining biomorphic shapes populating a barren landscape. However, Magritte, employed carefully chosen, naturalistically-presented objects in his haunting painting, The Central Story . The juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated objects suggests a cryptic meaning and otherworldliness, similar to the hybrid creatures common to exquisite corpse drawings. These two visual styles extend to other Surrealist media, including photography, sculpture, and film.

The Surrealist experience

Today, we tend to think of Surrealism primarily as a visual arts movement, but the group’s activity stemmed from much larger aspirations. By teaching how to circumvent restrictions that society imposed, the Surrealists saw themselves as agents of social change. The desire for revolution was such a central tenet that through much of the late 1920s, the Surrealists attempted to ally their cause with the French Communist party, seeking to be the artistic and cultural arm. Unsurprisingly, the incompatibility of the two groups prevented any alliance, but the Surrealists’ effort speaks to their political goals.

In its purest form, Surrealism was a way of life. Members advocated becoming flâneurs –urban explorers who traversed cities without plan or intent, and they sought moments of objective chance— seemingly random encounters actually fraught with import and meaning. They disrupted cultural norms with shocking actions, such as verbally assaulting priests in the street. They sought in their lives what Breton dubbed surreality , where one’s internal reality merged with the external reality we all share. Such experiences, which could be represented by a painting, photograph, or sculpture, are the true core of Surrealism.

Meret Oppenheim. Object , 1936. Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon, cup 4-3/8 inches in diameter; saucer 9-3/8 inches in diameter; spoon 8 inches long, overall height 2-7/8″ (The Museum of Modern Art)

The “Nonnational boundaries of Surrealism”*

Returning to The Surrealist Map of the World , let’s reconsider what it tells us about the movement. Shifts in scale are evident, as Russia dominates (likely a nod to the importance of the Russian Revolution). Africa and China are far too small, but Greenland is huge. The Americas are comprised of Alaska (perhaps another sly reference to Russia’s former control of this territory), Labrador, and Mexico, with a very small South America attached beneath. The United States and the rest of Canada are removed entirely. Much of Europe is also gone. France is reduced to the city of Paris, and Ireland appears without the rest of Great Britain. The only other city clearly indicated is Constantinople, pointedly not called by its modern name Istanbul. An anti-colonial diatribe, the Surrealists’s map removes colonial powers to create a world dominated by cultures untouched by western influence and participants in the Communist experiment. It is part utopian vision, part promotion of their own agenda, and part homage to their influences.

It also reminds us that Surrealism was an international movement. Although it was founded in Paris, pockets of Surrealist activity emerged in Belgium, England, Czechoslovakia, Mexico, the United States, other parts of Latin America, and Japan. Although Surrealism’s heyday was 1924 to the end of the 1940s, the group stayed active under Breton’s efforts until his death in 1966. An important influence on later artists within Abstract Expressionism, Art Brut, and the Situationists, Surrealism continues to be relevant to art history today.

*André Breton, “Nonnational Boundaries of Surrealism,” in Free Rein , trans. Michel Parameter and Jacqueline d’Amboise (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), pp. 7-18.

Additional resources:

Surrealism on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

André Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) Surrealism Reviewed: a selection of audio interviews and music (UbuWeb) Four Surrealist films by Man Ray Digital archive of Surrealist journals from Spain, Chile, and Argentina (in Spanish)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Surrealism”]

More Smarthistory images…

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Icon Link Plus Icon

What Was Surrealism?

By Rachel Wetzler

Rachel Wetzler

Senior Editor, Art in America

SURREALISM RECEIVED THE MUSEUM TREATMENT early in its history—early enough that André Breton, the movement’s charismatic ringleader and chief evangelist, was aggrieved at learning that he would not be allowed to dictate the selection and presentation of works, as he had for virtually every other Surrealist exhibition since the group’s 1925 debut at Galerie Pierre in Paris. Organized by Alfred H. Barr Jr., at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936, the show, “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism,” was conceived as a companion to “Cubism and Abstract Art,” held at the museum earlier that year, both part of a series of exhibitions that would, according to Barr, “present in an objective and historical manner the principal movements of modern art.” Yet if Barr recognized that Surrealism must be reckoned with, he was nevertheless equivocal about its significance, in a way that he was decidedly not about Cubism’s: “When [Surrealism] is no longer a cause or a cockpit of controversy,” he writes in the catalogue, “it will doubtless be seen to have produced a mass of mediocre and capricious pictures and objects, a fair number of excellent and enduring works of art, and even a few masterpieces.”

This comparative ambivalence extended to the show’s contextualization of the movement. Whereas “Cubism and Abstract Art” advanced a causal history of modernism, tracing a direct genealogy from the broken brushwork of Impressionism to the faceted planes of Cubism, and from Cubist dissection of form to the abstract geometry of Suprematism and De Stijl, “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” introduced a more haphazard lineage: the loose, transhistorical category of “fantastic art” encompassed an eclectic range of materials, from the work of premodern fabulists like Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Hieronymus Bosch, and William Blake, to art made by children and the mentally ill, advertisements, and even a Walt Disney cartoon. As Barr suggests, Surrealism is inherently resistant to the kind of formalist reading that anchored the previous exhibition: in the catalogue, he writes that under Breton’s leadership Surrealism springs from the ashes of Paris Dada after its 1922 demise, harnessing its predecessor’s anarchic anti-rationalism into a more systematic theoretical program, rooted in the exploration of the unconscious mind—but not in a corresponding aesthetic program. Surrealism was not a style, but a “mental attitude and a method of investigation,” as writer Georges Hugnet contends elsewhere in the show’s catalogue. This, for Barr, explains the fact that Surrealist artistic output tended in two formally irreconcilable directions: on the one hand, the dream imagery characteristic of Salvador Dalí, Yves Tanguy, and René Magritte, in which impossible scenes are rendered with naturalistic precision, and on the other, the biomorphic pseudo-abstractions of André Masson and Joan Miró, rooted in the practice of automatic drawing. Per Hugnet: for the Surrealists, “what a work of art expresses formally is of no importance—only its hidden content counts.”

Three decades later, with the 1968 exhibition “Dada, Surrealism and Their Heritage,” MoMA revisited the movement, this time retrospectively. In curator William Rubin’s account, two years after Breton’s death, European Surrealism is officially done as a living, breathing movement, the advanced art baton long since handed off to Abstract Expressionism and Pop in New York. While Rubin reiterates Barr’s sentiments about Surrealism’s privileging of a shared philosophy over a cohesive style, he nevertheless attempts to find a place for these unruly avant-gardes in MoMA’s essentially formalist narrative of modern art: “No matter what the radicality of an artist’s démarche, or his commitment to extrapictorial concerns, he sets out from some definition of art,” Rubin wrote in the show’s catalogue. “Hence, despite the postures assumed by some of the Dada and Surrealist artists, they were all in an enforced dialogue with the art that preceded them.” But even as Rubin sets out to bring Surrealism—scathingly, and in some circles fatally, dismissed by Clement Greenberg as literary, reactionary, and academic—back into the modernist fold, an element of Barr’s initial skepticism persists in his exhibition’s overdetermined narrative, which is, in the end, primarily concerned with the “heritage” of the show’s title. By the early 1940s, the Surrealist émigrés who flee Europe for New York during World War II have little left to say as artists in their own right, Rubin argues, but their arrival is nevertheless catalytic for the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. In this account, long dominant in Anglophone art history, Surrealism’s capital achievement is opening a door for a generation of wayward American painters, who quickly pass through it and never look back.

Critics and historians of modern art may have regarded Surrealism with suspicion but the public loved it: both MoMA shows drew significant crowds and traveled to multiple additional venues; that Rubin’s show was met by protesters—a mix of Yippies, Chicago Surrealists, and members of the anarchist art collective Black Mask—outraged at what they saw as the premature memorialization of a still-active movement only seemed to heighten its allure. In the popular imagination, Surrealism was stripped of its politics, understood instead as an art of outré hijinks embodied by the madcap figure of Dalí.

This picture was complicated by the 1978 exhibition “Dada and Surrealism Reviewed” at the Hayward Gallery in London, which placed the production of little magazines and journals at the center of Dada and Surrealist activity, both as the movements’ “principal platforms” for reaching an audience and their most coherent articulation of group identity and collective authorship. Emphasizing the central significance of magazines likewise directed new attention toward the Surrealist use of photography, both in terms of its treatment of the found image and the camera experiments of Surrealist artists.

Rosalind Krauss cites the show as a turning point in her 1981 essay “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism,” in which she argues that the conventional art-historical privileging of painting and sculpture by figures such as Rubin had led to a fundamental misreading of Surrealist art. For Krauss, photography was not only the medium in which the Surrealists made their most significant artistic contributions, but “the key to the dilemma of Surrealist style,” namely its confounding lack of one. Informed by semiotic theory, Krauss argues that the crux of Breton’s hazily defined concept of “convulsive beauty”—and thus Surrealist aesthetics as a whole—is “an experience of reality transformed into representation,” emblematized by the uncanny manipulations of the real produced by Surrealist photographers. Krauss elaborated on this argument in 1985 in the exhibition “L’Amour Fou: Photography and Surrealism,” co-curated with Jane Livingston, at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., but Krauss’s dense catalogue essays, simultaneously published in the journal October , were arguably more influential than the show itself, recasting Surrealism as an art of fetishistic transgression rather than baroque fantasy, and an ideal screen for theoretical projection.

“Surrealism Beyond Borders,” which debuted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York this past October and is currently on view at Tate Modern in London, attempts to shift the terms of Surrealist history once again. The show opens under the sign of exile: Marcel Jean’s Armoire Surréaliste (1941), a massive painting on hinged wooden panels bearing a trompe l’oeil rendering of a wardrobe’s doors and drawers opening to reveal a landscape stretching out into the distance. Made while the artist and his wife were stranded in Budapest—where they had moved temporarily from Paris in 1938 and then found themselves unable to return due to the war—it directs the Surrealist trope of everyday objects transformed into the stuff of dreams toward a more concrete, and politically poignant, desire for a secret passage to elsewhere. As signaled from the outset, the show’s conception of a Surrealism “beyond borders” is defined by people and concepts in motion, voluntarily or otherwise. Instead of a Paris-based interwar movement whose precepts and membership rolls were determined by Breton, Surrealism, in this telling, is an idea invented and reinvented in many times and places—Prague, Belgrade, Port au Prince, Mexico City, Tokyo, Cairo, Chicago, and, yes, Paris—with Breton’s inaugural circle one interconnected node among many. In a sense, the show proposes that Surrealism isn’t an art movement at all, but something more diffuse: a phenomenon, a network, an impulse in the air, or, as the show’s lead curators, Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale, put it in their catalogue essay, a model of “rhizomatic connectivity.”

The choice of Jean’s Armoire Surréaliste as an opening salvo also hints at other more subtle but no less significant historiographic revisions that the show proposes. The first is its relatively late date, after what is commonly held to be the heyday of Surrealism, which is posited here as roughly the movement’s midpoint rather than its end—in fact, the show includes more postwar objects than prewar ones. The second is its medium, painting, conveniently and perhaps conservatively restored to the center of the Surrealist story, with both photography and Surrealist objects—sculptural agglomerations of incongruous found materials—largely confined to their own dedicated subsections, presented at the Met in small side galleries.

Departing from Jean’s imaginary portal, the sprawling show unfolds as a sequence of broad thematic clusters that intermingle works from different periods and locations, leveling the priority of Paris and the heroic interwar phase. One of the largest groupings, “The Work of Dreams,” which was spread across a long wall at the Met in a playfully undulating hang, sets canonical examples of Surrealist dream imagery like Max Ernst’s Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924) alongside those likely to be familiar only to regional specialists. The Polish-Jewish painter Erna Rosenstein’s Ekrany (Screens, 1951) depicts the heads of her murdered parents floating, in grisaille, against a crisp blue backdrop, as if projected on one of the titular screens. Behind it is an eerie nocturnal forest, alluding to the nightmarish memory of the couple’s 1942 death in the woods at the hand of a smuggler who was supposed to help the family escape Nazi-occupied Poland. (The artist managed to survive the attack, and spent the rest of the war in hiding.) Skunder Boghossian’s Night Flight of Dread and Delight (1964), made while the Ethiopian-born artist was living in Paris, is a celestial panorama occupied by winged creatures soaring into outer space, synthesizing the influences of Coptic art, Négritude, the Surrealist paintings of Wifredo Lam and Roberto Matta, and the work of Nigerian magical realist writer Amos Tutuola.

Though the section “Beyond Reason,” which takes up the Surrealist antipathy toward logic and order, includes textbook contributions like René Magritte’s Time Transfixed (1938), portraying a miniature train hovering in midair as it speeds out of the fireplace of an elegant bourgeois interior, the wall text prioritizes the work of Japanese “Scientific Surrealists,” who responded to accusations of escapism from members of the country’s ascendant proletarian art movement by asserting they would use reason as a “weapon.” Koga Harue’s Umi (The Sea, 1929), for instance, among the show’s standout works, combines technological imagery from mass media sources—including depictions of a submarine, a German zeppelin, and a factory cross-section—into a mechanized seascape, with a young woman in a bathing suit and cap, copied from a postcard set depicting “Western beauties,” raising her arm to preside over the scene. Another section, “Revolution, First and Always,” juxtaposes Dalí’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) , 1936, a gruesome depiction of a decaying body pulling itself apart in a desolate landscape, with an untitled 1967 work depicting a crowded field of graphically outlined monsters with bloodied claws and fangs by Mozambican painter Malangatana Ngwenya, an allegory for his experiences of political persecution as a member of the Liberation Front of Mozambique fighting for independence from Portugal in the 1960s.

These thematic groupings are punctuated by smaller sections devoted to “convergence points,” framed as particularly instructive hotbeds of group activity: Paris, with its Bureau of Surrealist Research, founded in 1924, serving as both a publicity organ and a clearinghouse for information and correspondence; Cairo, whose group Art et Liberté /al-Fann wa-l-Hurriyya issued a 1938 manifesto, “Long Live Degenerate Art!,” proclaiming art’s absolute independence from any state ideology; Mexico City, where many European exiles, including Breton, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Benjamin Péret, Wolfgang Paalen, and Alice Rahon, were drawn during and after World War II, making contacts with existing avant-garde groups like the circle around the journal Contemporáneos , eager for alternatives to the dominant muralism; and Chicago, where a countercultural Surrealist group formed in 1966, devoted primarily to the production of antiwar agitprop, direct action, and underground publications rather than conventional artworks. More unwieldy is “Haiti, Cuba, Martinique,” which doesn’t so much name a meeting point, or three, for that matter, as identify the homes of influential artists and writers who intermittently left for the metropole and returned, among them the Cuban painter Lam and Martinican writers Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, taking Surrealism and transforming it into a more rigorous and politically committed vision of antifascist, anticolonial liberation. Conversely, other sections function as case studies of lesser-known figures—the Illinois-born Black poet and jazz musician Ted Joans; documentary photographer Eva Sulzer, part of the circle around the Mexico City–based journal Dyn ; and the Spanish painter Eugenio Granell—who exemplify the show’s emphasis on Surrealism as an art of “travel, exile, [and] displacement” by rarely staying in one place for long. Granell, for instance, a leftist veteran of the Spanish Civil War, fled Spain after the fall of the republic, initially for the Dominican Republic, until that country’s military dictatorship sent him into exile once again, then Guatemala, where he was soon driven out as a result of his opposition to an increasingly influential faction of Stalinist artists and writers. Eventually offered a teaching position at the University of Puerto Rico in 1950, where he remained for seven years before relocating to New York, he played an influential role in introducing Surrealism to the island: displayed alongside Granell’s own creaturely paintings are works by the members of El Mirador Azul (The Blue Lookout), a Surrealist group formed by his students, attesting to the long aftereffects of these itinerant wanderings.

“Surrealism Beyond Borders” arrives at the tail end of a decade-long wave of “global exhibitions” like “Other Primary Structures” at the Jewish Museum (2014) and “International Pop” at the Walker Art Center (2015): revisionist histories of canonical movements heretofore assumed to be the exclusive province of Western Europe and North America, now revealed to be far more dynamic and geographically dispersed. What distinguishes this one is that Surrealism was explicitly international from the outset; this was, indeed, part of its mythology and self-image. Surrealist circles sprang up around the world—the first ones, in Tokyo and Belgrade, appeared almost immediately after the Manifesto’s publication—with varying degrees of allegiance to Breton, adapting Surrealist ideas to local circumstances. Surrealism could be malleable enough to offer artists in different places whatever they needed from it: a rejection of the status quo, of bourgeois order, of colonial power, of social and political restriction. The Paris circle was also far from exclusively French, with many of its most recognizable participants arriving from abroad: Man Ray, Max Ernst, Magritte, Dalí, Miró. All this is acknowledged even in conventional accounts like Barr’s and Rubin’s, but taken primarily as a sign of Breton’s enlightened despotism and the Paris movement’s resounding success in disseminating its vision of the avant-garde. The show’s revision, then, is primarily a shift in priority or emphasis rather than a wholesale redefinition.

In eschewing chronology and, for the most part, geography, as organizing criteria, the curators wish to push against the perception that Surrealism is primarily a Parisian movement, bequeathed by Breton to provincial, often colonial, satellites. Rejecting the notion that the Surrealism practiced in Colombia or Turkey in the 1950s is merely a belated reiteration of the innovations of 1920s France, they insist, instead, that artists outside Breton’s immediate orbit had just as much claim to Surrealist strategies and watchwords.

Yet this thematic approach also largely lets Breton and company set the terms, unquestioningly accepting the categories and concepts that the Paris circle held up as central to Surrealist theory and practice, and slotting in works from elsewhere accordingly, giving each grouping a grab-bag quality. In many of the sections, the work is genuinely remarkable enough to distract from this categorical flimsiness; elsewhere it shows. In the wall text for the section devoted to Automatism, the concept is polemically introduced by way of the short-lived 1940s journal Surreal , based in Aleppo, rather than Breton’s first Surrealist Manifesto, though neither the journal nor the Aleppo Surrealists’ work is actually on view. Instead, it is represented by an eclectic and mostly unremarkable group of works, largely characterized by anodyne abstraction. A massive canvas by the French painter Jean Degottex, L’espace dérobé (The Hidden Space, 1955), featuring two informel -ish slashes of muddy color on a grubby white ground, is perhaps the show’s nadir: an utterly nondescript work taking up too much wall space, with little to say about Surrealism’s postwar trajectory—particularly given that the artist never joined the group—except that, according to the wall text, Breton happened to be a fan. What is the advantage of including this work as an exemplar of automatism instead of, say, one of Masson’s 1920s sand paintings, for which he threw sand over spontaneously applied areas of wet gesso, allowing the resulting forms and the chains of associations they inspired to dictate the rest of the composition, if not simply for the sake of being noncanonical?

Moreover, this approach threatens to obfuscate as much as illuminate, avoiding as it does sufficient historical context to explain when, why, and how Surrealist practice took hold in different places, and what it meant at different moments, under varying sociopolitical circumstances. Is the everyday made strange in Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer’s Byt (The Flat, 1968)—a stop-motion short clandestinely produced in the run-up to the Prague Spring, in which a man is held captive by his seemingly possessed apartment—coterminous with that of Brassaï’s “Involuntary Sculptures” (1932), close-up photographs of found detritus, made monumental by the camera’s framing, or Raoul Ubac’s Le Combat des Penthésilées (1937), a solarized tangle of fragmented bodies, titled after Heinrich von Kleist’s 1808 tragedy about the mythological queen of the Amazons? All three are yoked together in the section “The Uncanny in the Everyday,” which ostensibly explores how Surrealist photographers “tapped into the rich vein of estrangement embedded in the ordinary world,” but in practice flattens radically disparate work into an almost undifferentiated mass of weird pictures. The same might be said for almost all the show’s thematic sections. While the substantial scholarly catalogue fills in many of these contextual blanks, its form—dozens of short essays homing in on particular circles or phenomena—prevents a syncretic view. That this is by design doesn’t make it less frustrating: the show dedicates an entire subsection to the fascinating figure of Ted Joans, who committed himself to Surrealism as a child after encountering the movement in copies of avant-garde periodicals like Minotaure tossed out by his aunt’s white employers, formally joining the movement after a chance encounter with Breton in Paris in the early 1960s, yet after multiple visits to the exhibition and a close read of the catalogue, I remain unsure of who else belonged to the group at the time of his arrival.

Nevertheless, the exhibition’s accomplishments are undeniable, not least in the sheer volume of research undertaken by the curatorial team (D’Alessandro and Hale, along with Carine Harmand, Sean O’Hanlan, and Lauren Rosati), highlighting any number of heretofore marginal figures in the annals of Surrealism whose future prominence now seems assured. Its most decisive intervention is in putting to rest the long-held belief that Surrealism had sputtered out by the onset of World War II, just as art-world hegemony passed from Paris to New York: as the show makes abundantly clear, outside that particular Atlantic axis, Surrealism took new shape in response to a radically reoriented postwar world order.

But there is a fundamental question that the show refuses to answer even provisionally, and without which its narrative collapses under the weight of methodological indecision: what makes an artist a Surrealist? The show’s criteria for inclusion is murky, encompassing both those who explicitly identified with Surrealist groups and “fellow travelers” who participated in Surrealist activities or circles without ever formally joining, along with artists like Hector Hyppolite and Maria Izquierdo, whose works were claimed by Breton for Surrealism, regardless of their own interests and motivations, and others with no direct connection to Surrealism at all, among them Yayoi Kusama (who has explicitly denied a Surrealist element to her work) and the Iranian photojournalist Kaveh Golestan, killed by a landmine on assignment in Iraq in 2003, included on the basis of a striking, if uncharacteristic, 1976 photographic series, “Az Div o Dad” (Of Demon and Beast), comprising composites of Qajar Dynasty monarchs and animals made by holding archival images in front of the camera with the shutter left open. On the other hand, I will admit to being stumped by Kitawaki Noboru’s spare and schematic painting Diagram of I Ching Divination (Heaven and Earth) , 1941, which seems fundamentally remote from Surrealist concerns as elaborated elsewhere in the exhibition, regardless of the artist’s self-identification. In attempting to keep the tent as big as possible, the exhibition dilutes the definition to the point of meaninglessness, exacerbated by the nonchronological installation, which elides the particulars of each artist’s encounters with Surrealism in favor of perceived affinities and thematic allegiances.

I suspect that this sense of evasiveness, dubiously spun as an advantage in D’Alessandro and Gale’s surprisingly circumlocutory introductory essay, reflects a profound anxiety about the very enterprise of a “global exhibition,” and the gambit of canon formation, or reformation, that it inevitably entails. Hesitant to replace old protagonists with new ones, to pick winners, to pluck new masterpieces out of obscurity, the show declines to commit to any position at all, preferring a view of Surrealism as undefinable and amorphous—in today’s parlance, more a vibe than anything else. But as a result, the Pope in Paris paradoxically looms larger than ever, even if he rarely appears outright: in the absence of an affirmative definition of what Surrealism is or was, all routes eventually pass through Breton, as the shared point of contact who holds together heterogeneous artists and groups. But if the show fails to convincingly knock Breton off his pedestal, or to advance a coherent narrative to rival the received ones it wishes to displace, it is generative in its breadth, gesturing toward the possibility of more complete and complex histories of Surrealism that may one day be written.

This article appears in the April 2022 issue, pp. 44 –51 .

Paul McCartney Is Auctioning Off the Iconic Beatles Boots He Wore at the 2012 London Olympics

How to watch the 2024 acm awards red carpet pre-show, pixel 9 phones revealed in massive leak ahead of google i/o 2024, bridgeathletic training tool acquires game plan platform, the best yoga mats for any practice, according to instructors.

ARTnews is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Art Media, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Surrealism and Film

Introduction, general overviews.

- Introductions to Surrealism

- Film Studies

- Surrealist Film as Avant-Garde and Experimental Cinema

- Popular Cinema and Surrealism

- Theoretical Responses to Surrealism and Film

- Luis Buñuel

- Other Surrealist Filmmakers and Scenarists

- Special Issues Devoted to Surrealism and Film

- Film Archives

- Surrealist Films Distributed by Commercial and Nonprofit Vendors

- BFI Classics

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Film Theory

- French Cinema

- Jean Cocteau

- Modernism and Film

- Pedro Almodóvar

- Psychoanalytic Film Theory

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Jacques Tati

- Media Materiality

- The Golden Girls

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Surrealism and Film by Robin Walz LAST REVIEWED: 19 December 2012 LAST MODIFIED: 19 December 2012 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0139