1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Existentialism

Author: Addison Ellis Category: Phenomenology and Existentialism , Ethics Word Count: 1000

Video below

1. Mr. Green

Mr. Green is many things: a teacher, a husband, a father, a college graduate, and a medical patient, to name a few. Some of his features may be counted as accomplishments, others failures, and yet others unlucky accidents thrust upon him by the world. But is this all there is to Mr. Green?

According to the philosophical tradition of Existentialism , something is missing in this characterization. For the existentialist, we are not merely a collection of facts; we are also self-conscious, living, caring beings . While trees, seagulls, and fish are all similarly alive , they do not live the same sorts of lives that we do. Existentialism is the philosophical science of our peculiar sorts of lives. 1

Our lives are ongoing activities . Mr. Green’s existence, just like the existence of every similarly self-conscious, caring being, is more than a series of events or a set of facts. In providing such an understanding, Existentialism breathes new life into old ideas about the nature of value, freedom, and even more broadly into questions about the nature of reality and knowledge. In this essay, we will restrict our focus to what existentialists have to say about human nature and living a meaningful life. 2

2. Existence Precedes Essence

Many philosophers, both historical and contemporary, believe that the way something is is determined by its essence . That is, essences are fixed determinants of the way things are.

Those who follow this line of thought may take essences to be the non-physical and eternal standards to which things conform. 3 Thus, the essence of a table is what determines table-like behavior. Likewise, the essence of a human being is what determines what a human being is like. These fixed determinants can range from principles given by God to those we attribute to society.

Martin Heidegger helpfully points out that we often speak of the way “one” does things, referring to no one in particular. We say things like “this is the way one does x ,” because doing x correctly means doing it in accordance with some pre-established standard. 4 But Heidegger believes that this way of thinking should not extend to our ways of living. That is, we should not understand ourselves as living correctly only when we live “as one lives.” Existentialism reverses this picture by suggesting that it is our living which determines our essence, and not the other way around.

Let’s go back to Mr. Green. In order to understand what sort of being he is, we must understand that who he is is not a fact he was born with, nor is it a fact that was established merely after some important events in his life unfolded. He is who he is because of what he chooses , and one can never stop choosing. For even by trying to decide that I will no longer make choices, I am making the choice not to choose. Jean-Paul Sartre, the most famous of the historical existentialists, expresses the idea that we are who we make ourselves, and not who we are pre-determined to be, with a concise slogan: “existence precedes essence.” 5

3. Freedom & Authenticity

If Sartre is right and our lives are essentially up to us, then existentialists must also be committed to a robust kind of freedom , since we are not determined by what happens to us.

But if Mr. Green’s essence is up to him, and he’s free to craft his essence as he pleases, then on what standards does he draw to guide himself in his crafting? It would seem that existentialists cannot simply draw from a set of independently existing standards. If this were so, then who we are is again simply a matter of conforming to some pre-established standards.

If the standards are up to us, then why should we choose any one set of standards over any other? That is, how can we make sense of the idea that there is a right way to live and a wrong way to live if there is no external standard for judging whether we have made the right choice ? 6

This is a difficult issue in Existentialism, one that is grappled with by all the major figures in the tradition. The answer we will entertain here is that it is possible to find a standard within our own activities that determines whether they are being performed well or poorly. This is what existentialists refer to as authenticity . 7

Mr. Green, knowing that he has terminal lung cancer, can arrange the final years of his life in a variety of ways; it is up to him how he will structure his remaining time. But there are two ways in which he can choose:

(i) he can see his choices as simply thrust upon him by the world—i.e., he can believe that he really doesn’t have a choice at all,

(ii) he can see his choices as his own while taking full responsibility for them.

Only by acting in this way is Mr. Green acting authentically , since it is only under these conditions that he is true to himself. Acting inauthentically , then, involves excusing oneself from responsibility by ignoring one’s freedom. The existentialist hopes to have shown that despite the lack of external guidance, we are perfectly capable of telling from within our own activities whether we are acting authentically or inauthentically. 8

4. Conclusions

Existentialism gives us some tools for understanding (i) our essence, and (ii) how it is possible to live a meaningful life.

The ideas defended by existentialists have been thought to have both positive and negative implications for us. On the one hand, our lives are not determined by God, society, or contingent circumstances; on the other hand, absolute freedom can be a burden. As Sartre puts it, “man is condemned to be free.” 9 That is, it was never up to us to be free, and we cannot cease to be free. Since we must be free, and because freedom entails responsibility, we can never opt out of being responsible. Thus we are simultaneously unencumbered and encumbered by our freedom to choose who we will be.

1 This is not to denigrate the lives of things radically different from us, but merely to point out that paradigm human creatures live peculiar sorts of lives. The demarcating line here between lives like ours and lives unlike ours needn’t be drawn along purely biological lines. There are potentially things—certain non-human animals, futuristic artificially intelligent systems—that have lives like ours, and whose lives are properly studied by Existentialism. Similarly, there are some biological humans—the very young, the severely mentally handicapped—whose lives are not like ours , and hence, whose lives are not properly studied by Existentialism.

2 Existential themes can be traced as far back as St. Augustine in his Confessions . Most philosophers today agree, however, that 19 th- Century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and 19th-Century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche did much to provide the framework for what Existentialism would become in its more definitive era. The major figures of Existentialism include not only Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, but also (perhaps more importantly) Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger, in the 20 th century.

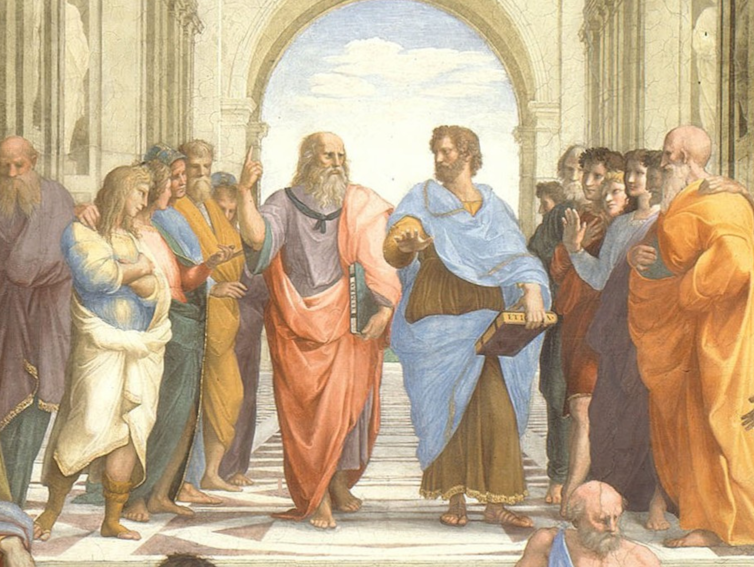

3 What Plato calls “forms.”

4 This is an expression of what Heidegger calls the They-self, Being and Time S ection 129

5 Sartre, Existentialism Is a Humanism (20)

6 There is some debate about whether Existentialism is actually a moral theory. One reason for the doubt is precisely this one – that there is nothing action-guiding about Existentialism.

7 Steven Crowell makes this point in his SEP article when discussing Nietzsche’s idea of a ‘ruling instinct.’

8 There is a serious worry here that must be addressed by the existentialist, and I will leave it as an exercise for the reader. While it seems better to act authentically than to act inauthentically, don’t we need to meet even more standards in order to count as living a truly good life? In other words, we might worry about whether authenticity is the only guiding principle that we really need. Perhaps it is possible to be an authentic genocidal dictator. If so, then perhaps Existentialism does not, on its own, suffice as a moral theory.

9 Sartre, op. cit . (29)

Crowell, Steven. “Existentialism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Stanford University, 23 Aug. 2004. Web. 18 Apr. 2014.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time . Trans. John Macquarrie. Ed. Edward Robinson. New York: HarperPerennial/Modern Thought, 2008.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism Is a Humanism . Ed. John Kulka and Arlette Elkaïm-Sartre. New Haven: Yale UP, 2007.

Related Essays

African American Existentialism: DuBois, Locke, Thurman, and King by Anthony Sean Neal

Happiness by Kiki Berk

Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? by Matthew Pianalto

Moral Luck by Jonathan Spelman

Free Will and Free Choice by Jonah Nagashima

Free Will and Moral Responsibility by Chelsea Haramia

About the Author

Addison Ellis is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at The American University in Cairo. His interests include Kant and Post-Kantian European Philosophy, with special attention to the topics of self-consciousness, ontology, and cognitive capacities and attitudes. philpeople.org/profiles/addison-ellis

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 7 thoughts on “ existentialism ”.

- Pingback: The Meaning of Life: What’s the Point? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: African American Existentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Existentialism: A Collection of Online Resources and Key Quotes - The Daily Idea

- Pingback: Existentialism and Caterialism – The Babel of Languages and the Substrate of Nature

- Pingback: Introduction to Existentialism – Naung Mon Oo

Comments are closed.

What makes a good life? Existentialists believed we should embrace freedom and authenticity

Indigenous Fellow - Assistant Professor in Philosophy and History, Bond University

Disclosure statement

Oscar Davis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bond University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

How do we live good, fulfilling lives?

Aristotle first took on this question in his Nicomachean Ethics – arguably the first time anyone in Western intellectual history had focused on the subject as a standalone question.

He formulated a teleological response to the question of how we ought to live. Aristotle proposed, in other words, an answer grounded in an investigation of our purpose or ends ( telos ) as a species.

Our purpose, he argued, can be uncovered through a study of our essence – the fundamental features of what it means to be human.

Ends and essences

“Every skill and every inquiry, and similarly every action and rational choice, is thought to aim at some good;” Aristotle states, “and so the good has been aptly described as that at which everything aims.”

To understand what is good, and therefore what one must do to achieve the good, we must first understand what kinds of things we are. This will allow us to determine what a good or a bad function actually is.

For Aristotle, this is a generally applicable truth. Take a knife, for example. We must first understand what a knife is in order to determine what would constitute its proper function. The essence of a knife is that it cuts; that is its purpose. We can thus make the claim that a blunt knife is a bad knife – if it does not cut well, it is failing in an important sense to properly fulfil its function. This is how essence relates to function, and how fulfilling that function entails a kind of goodness for the thing in question.

Of course, determining the function of a knife or a hammer is much easier than determining the function of Homo sapiens , and therefore what good, fulfilling lives might involve for us as a species.

Aristotle argues that our function must be more than growth, nutrition and reproduction, as plants are also capable of this. Our function must also be more than perception, as non-human animals are capable of this. He thus proposes that our essence – what makes us unique – is that humans are capable of reasoning.

What a good, flourishing human life involves, therefore, is “some kind of practical life of that part that has reason”. This is the starting point of Aristotle’s ethics.

We must learn to reason well and develop practical wisdom and, in applying this reason to our decisions and judgements, we must learn to find the right balance between the excess and deficiency of virtue.

It is only by living a life of “virtuous activity in accordance with reason”, a life in which we flourish and fulfil the functions that flow from a deep understanding of and appreciation for what defines us, that we can achieve eudaimonia – the highest human good.

Read more: Friday essay: how philosophy can help us become better friends

Existence precedes essence

Aristotle’s answer was so influential that it shaped the development of Western values for millennia. Thanks to philosophers and theologians such as Thomas Aquinas , his enduring influence can be traced through the medieval period to the Renaissance and on to the Enlightenment.

During the Enlightenment, the dominant philosophical and religious traditions, which included Aristotle’s work, were reexamined in light of new Western principles of thought.

Beginning in the 18th century, the Enlightenment era saw the birth of modern science, and with it the adoption of the principle nullius in verba – literally, “take nobody’s word for it” – which became the motto of the Royal Society . There was a corresponding proliferation of secular approaches to understanding the nature of reality and, by extension, the way we ought to live our lives.

One of the most influential of these secular philosophies was existentialism. In the 20th century, Jean-Paul Sartre , a key figure in existentialism, took up the challenge of thinking about the meaning of life without recourse to theology. Sartre argued that Aristotle, and those who followed in Aristotle’s footsteps, had it all back-to-front.

Existentialists see us as going about our lives making seemingly endless choices. We choose what we wear, what we say, what careers we follow, what we believe. All of these choices make up who we are. Sartre summed up this principle in the formula “existence precedes essence”.

The existentialists teach us that we are completely free to invent ourselves, and therefore completely responsible for the identities we choose to adopt. “The first effect of existentialism,” Sartre wrote in his 1946 essay Existentialism is a Humanism , “is that it puts every man in possession of himself as he is, and places the entire responsibility for his existence squarely upon his own shoulders.”

Crucial to living an authentic life, the existentialists would say, is recognising that we desire freedom above everything else. They maintain we ought never to deny the fact we are fundamentally free. But they also acknowledge we have so much choice about what we can be and what we can do that it is a source of anguish. This anguish is a felt sense of our profound responsibility.

The existentialists shed light on an important phenomenon: we all convince ourselves, at some point and to some extent, that we are “bound by external circumstances” in order to escape the anguish of our inescapable freedom. Believing we possess a predefined essence is one such external circumstance.

But the existentialists provide a range of other psychologically revealing examples. Sartre tells a story of watching a waiter in a cafe in Paris. He observes that the waiter moves a little too precisely, a little too quickly, and seems a little too eager to impress. Sartre believes the waiter’s exaggeration of waiter-hood is an act – that the waiter is deceiving himself into being a waiter.

In doing so, argues Sartre, the waiter denies his authentic self. He has opted instead to assume the identity of something other than a free and autonomous being. His act reveals he is denying his own freedom, and ultimately his own humanity. Sartre calls this condition “bad faith”.

Read more: Finding your essential self: the ancient philosophy of Zhuangzi explained

An authentic life

Contrary to Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia , the existentialists regard acting authentically as the highest good. This means never acting in such a way that denies we are free. When we make a choice, that choice must be fully ours. We have no essence; we are nothing but what we make for ourselves.

One day, Sartre was visited by a pupil, who sought his advice about whether he should join the French forces and avenge his brother’s death, or stay at home and provide vital support for his mother. Sartre believed the history of moral philosophy was of no help in this situation. “You are free, therefore choose,” he replied to the pupil – “that is to say, invent”. The only choice the pupil could make was one that was authentically his own.

We all have feelings and questions about the meaning and purpose of our lives, and it is not as simple as picking a side between the Aristotelians, the existentialists, or any of the other moral traditions. In his essay, That to Study Philosophy is to Learn to Die (1580), Michel de Montaigne finds what is perhaps an ideal middle ground. He proposes “the premeditation of death is the premeditation of liberty” and that “he who has learnt to die has forgot what it is to be a slave”.

In his typical style of jest, Montaigne concludes: “I want death to take me planting cabbages, but without any careful thought of him, and much less of my garden’s not being finished.”

Perhaps Aristotle and the existentialists could agree that it is just in thinking about these matters – purposes, freedom, authenticity, mortality – that we overcome the silence of never understanding ourselves. To study philosophy is, in this sense, to learn how to live.

- Jean-Paul Sartre

- Existentialism

- Essentialism

Case Management Specialist

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Existentialism Is a Humanism

Jean-paul sartre, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Jean-Paul Sartre

Few philosophers have been as famous in their own life-time as Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–80). Many thousands of Parisians packed into his public lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism , towards the end of 1945 and the culmination of World War 2. That lecture offered an accessible version of his difficult treatise, Being and Nothingness (1943), which had been published two years earlier, and it also responded to contemporary Marxist and Christian critics of Sartre’s “existentialism”. Sartre was much more than just a traditional academic philosopher, however, and this begins to explain his renown. He also wrote highly influential works of literature, inflected by philosophical concerns, like Nausea (1938), The Roads to Freedom trilogy (1945–49), and plays like No Exit (1947), Flies (1947), and Dirty Hands (1948), to name just a few. He founded and co-edited Les Temps Modernes and mobilised various forms of political protest and action. In short, he was a celebrity and public intellectual par excellence, especially in the period after Liberation through to the early 1960s. Responding to some calls to prosecute Sartre for civil disobedience, the then French President Charles de Gaulle replied that you don’t arrest Voltaire.

While Sartre’s public renown remains, his work has had less academic attention in the last thirty or so years ago, and earlier in France, dating roughly from the rise of “post-structuralism” in the 1960s. Although Gilles Deleuze dedicated an article to his “master” in 1964 in the wake of Sartre’s attempt to refuse the Nobel Prize for literature (Deleuze 2004), Michel Foucault influentially declared Sartre’s late work was a “magnificent and pathetic attempt of a man of the nineteenth century to think the twentieth century” (Foucault 1966 [1994: 541–2]) [ 1 ] . In this entry, however, we seek to show what remains alive and of ongoing philosophical interest in Sartre, covering many of the most important insights of his most famous philosophical book, Being and Nothingness . In addition, significant parts of his oeuvre remain under-appreciated and thus we seek to introduce them. Little attention has been given to Sartre’s earlier, psychologically motivated philosophical works, such as Imagination (1936) or its sequel, The Imaginary (1940). Likewise, few philosophers have seriously grappled with Sartre’s later works, including his massive two-volume Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), or his various works in existential psychoanalysis that examine the works of Genet and Baudelaire, as well as his multi-volume masterpiece on Flaubert, The Family Idiot (1971–2). These are amongst the works of which Sartre was most proud and we outline some of their core ideas and claims.

1. Life and Works

2. transcendence of the ego: the discovery of intentionality, 3. imagination, phenomenology and literature, 4.1. negation and freedom, 4.2 bad faith and the critique of freudian psychoanalysis, 4.3 the look, shame and intersubjectivity, 5. existential psychoanalysis and the fundamental project, 6. existentialist marxism: critique of dialectical reason, 7. politics and anti-colonialism, a. primary literature, b. secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

Sartre’s life has been examined by many biographies, starting with Simone de Beauvoir’s Adieux (and, subsequently, Cohen-Solal 1985; Levy 2003; Flynn 2014; Cox 2019). Sartre’s own literary “life” exemplifies trends he thematized in both Words and Being and Nothingness , summed up by his claim that “to be dead is to be prey for the living” (Sartre 1943 [1956: 543]). Sartre himself was one of the first to undertake such an autobiographical effort, via his evocation of his own childhood in Words (1964a)—in which Sartre applies to himself his method of existential psychoanalysis, thereby complicating this life/death binary.

Like many of his generation, Sartre lived through a series of major cultural and historical events that his existential philosophy responded to and attempted to shape. He was born in 1905 and died in 1980, spanning most of the twentieth century and the trajectory that the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm refers to as the “age of extremes”, a period that was also well-described in the middle of that century in Albert Camus’ The Rebel , notwithstanding that the reception of Camus’ book in Les Temps Modernes in 1951–2 caused Sartre and Camus to very publicly fall out.

The major events of Sartre’s life seem relatively clear, at least viewed from an external perspective. A child throughout World War 1, he was a young man during the Great Depression but born into relative affluence, brought up by his grandmother. At least as presented in Word s, Sartre’s childhood was filled with books, the dream of posterity and immortality in those books, and in which he grappled with his loss of the use of one eye and encountered the realities of his own appearance revealed through his mother’s look after a haircut—suffice to say, he was not classically beautiful.

Sartre’s education, by contrast, was classical—the École Normale Supérieure. His education at the ENS was oriented around the history of philosophy, and the influential bifurcation of that time between the neo-Kantianism of Brunschvicg and the vitalism of Bergson. While Sartre failed his first attempt at the aggregation, apparently by virtue of being overly ambitious, on repeating the year he topped the class (de Beauvoir was second, at her first attempt and at the age of 21, then the youngest to complete). Sartre then taught philosophy at various schools, notably at Le Havre from 1931–36 and while he was composing his early philosophy and his great philosophical novel, Nausea . He never entered a classical university position.

Although Sartre’s philosophical encounter with phenomenology had already occurred (around 1933), which de Beauvoir described as causing him to turn pale with emotion (de Beauvoir 1960 [1962: 112]), with the onset of World War 2 Sartre merged those philosophical concerns with more obviously existential themes like freedom, authenticity, responsibility, and anguish, as translated into English from the French angoisse by both Hazel Barnes and Sarah Richmond. He was a Meteorologist in Alsace in the war and was captured by the German Army in 1940 and imprisoned for just under a year (see War Diaries ). During this socio-political turmoil, Sartre remained remarkably prolific. Notable publications include his play, No Exit (1947), Being and Nothingness (1943), and then completing Existentialism is a Humanism (1946), Anti-semite and Jew (1946), and founding and coediting Les Temps Modernes , commencing from 1943 (Sartre’s major contributions are collected in his series Situations , especially volume V).

Sartre continued to lead various social and political protests after that period, especially concerning French colonialism (see section 7 below). By the time of the student revolutions in May 1968 he was no longer quite the dominant cultural and intellectual force he had been, but he did not retreat from public life and engagement and died in 1980. Estimates of the numbers of those attending his funeral procession in Paris range from 50–100,000 people. Sartre had been in the midst of a collaboration with Benny Levy regarding ethics, the so-called “Hope Now” interviews, whose status remain somewhat controversial in Sartrean scholarship, given the interviews were produced in the midst of Sartre’s illness and shortly before he died, and the fact that the relevant audio-recordings are not publicly available.

One of the most famous foundational moments of existentialism concerns Sartre’s discovery of phenomenology around the turn of 1932/3, when in a Parisian bar listening to his friend Raymond Aron’s description of an apricot cocktail (de Beauvoir 1960 [1962: 135]). From this moment, Sartre was fascinated by the originality and novelty of Husserl’s method, which he identified straight away as a means to fulfil his own philosophical expectations: overcoming the opposition between idealism and realism; getting a view on the world that would allow him “to describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and extract philosophy from the process”. Sartre became immediately acquainted with Emmanuel Levinas’s early translation of Husserl’s Cartesian Meditations and his introductory book on Husserl’s theory of intuition. He spent the following year in Berlin, so as to study more closely Husserl’s method and to familiarise himself with the works of his students, Heidegger and Scheler. With Levinas, and then later with Merleau-Ponty, Ricœur, and Tran Duc Thao, Sartre became one of the first serious interpreters and proponent of Husserl’s phenomenology in France.

While he was studying in Berlin, Sartre tried to convert his study of Husserl into an article that documents his enthusiastic discovery of intentionality. It was published a few years later under the title “Intentionality: a fundamental idea of Husserl’s phenomenology”. This article, which had considerable influence over the early French reception of phenomenology, makes explicit the reasons Sartre had to be fascinated by Husserl’s descriptive approach to consciousness, and how he managed to merge it with his previous philosophical concerns. Purposefully leaving aside the idealist aspects of Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology, Sartre proposes a radicalisation of intentionality that stresses its anti-idealistic potential. Against the French contemporary versions of neo-Kantianism (Brochard, Lachelier), and more particularly against the kind of idealism advocated by Léon Brunschvicg, Sartre famously claims that intentionality allows us to discard the metaphysical oppositions between the inner and outer and to renounce to the very notion of the interiority of consciousness. If it is true, as Husserl states, that every consciousness is consciousness of something, and if intentionality accounts for this fundamental direction that orients consciousness towards its object and beyond itself, then, Sartre concludes, the phenomenological description of intentionality does away with the illusion that makes us responsible for the way the world appears to us. According to Sartre’s radicalised reading of Husserl’s thesis, intentionality is intrinsically realistic: it lets the world appear to consciousness as it really is , and not as a mere correlate of an intellectual act. This realistic interpretation, being perfectly in tune with Sartre’s lifelong ambition to provide a philosophical account of the contingency of being—its non-negotiable lack of necessity—convinced him to adopt Husserl’s method of phenomenological description.

While he was still in Berlin, Sartre also began to work on a more personal essay, which a few years later resulted in his first significant philosophical contribution, Transcendence of the Ego . With this influential essay Sartre engages in a much more critical way with the conception of the “transcendental ego” presented in Husserl’s Ideas and defends his realistic interpretation of intentionality against the idealistic tendencies of Husserl’s own phenomenology after the publication of Logical Investigations . Stressing the irreducible transparency of intentional experience—its fundamental orientation beyond itself towards its object, whatever this object may be—Sartre distinguishes between the dimensions of our subjective experiences that are pre-reflectively lived through, and the reflective stance thanks to which one can always make their experience the intentional object towards which consciousness is oriented. One of Sartre’s most fundamental claims in Transcendence of the Ego is that these two forms of consciousness cannot and must not be mistaken with one another: reflexive consciousness is a form of intentional consciousness that takes one’s own lived-experiences as its specific object, whereas pre-reflexive consciousness need not involve the intentional distance to the object that the act of reflection entails. In regard to self-consciousness, Sartre argues there is an immediate and non-cognitive form of self-awareness, as well as reflective forms of self-consciousness. The latter is unable to give access to oneself as the subject of unreflected consciousness, but only as the intentional object of the act of reflection, i.e., the Ego in Sartre’s terminology. The Ego is the specific object that intentional consciousness is directed upon when performing reflection—an object that consciousness “posits and grasps […] in the same act” (Sartre 1936a [1957: 41; 2004: 5]), and that is constituted in and by the act of reflection (Sartre 1936a [1957: 80–1; 2004: 20]). Instead of a transcendental subject, the Ego must consequently be understood as a transcendent object similar to any other object, with the only difference that it is given to us through a particular kind of experience, i.e., reflection. The Ego, Sartre argues, “is outside, in the world . It is a being of the world, like the Ego of another” (Sartre 1936a [1957: 31; 2004: 1]).

This critique of the transcendental Ego is less opposed to Husserl than it may seem, notwithstanding Sartre’s reservations about the transcendental radicalisation of Husserl’s phenomenology. The neo-Humean claim that the “I” or Ego is nowhere to be found “within” ourselves remains faithful to the 5th Logical Investigation , in which Husserl had initially followed the very same line of reasoning (see Husserl 1901 [2001: vol. 2, 91–93]), before developing a transcendental methodology that substantially modified his approach to subjectivity (as exposed in particular in Husserl 1913 [1983]). However, for the Husserl of the Ideas Pertaining to a Phenomenology (published in 1913), the sense in which a perceptual object, which is necessarily seen from one side but also presented to us as a unified object (involving other unseen sides), requires that there be a unifying structure within consciousness itself: the transcendental ego. Sartre argues that such an account would entail that the perception of an object would always also involve an intermediary perception—such as some kind of perception or consciousness of the transcendental ego—thus threatening to disrupt the “transparency” or “translucidity” of consciousness. All forms of perception and consciousness would involve (at least) these two components, and there would be an opaqueness to consciousness that is not phenomenologically apparent. In addition, it appears that Husserl’s transcendental ego would have to pre-exist all of our particular actions and perceptions, which is something that the existentialist dictum “existence precedes essence”, which we will explicate shortly, seems committed to denying. Without considering here the extent to which Husserl can be defended against these charges, Sartre’s general claim is that the notion of a self or ego is not given in experience. Rather, it is something that is not immanent but transcendent to pre-reflective experience. The Ego is the transcendent object of one’s reflexive experience, and not the subject of the pre-reflective experience that was initially lived (but not known).

Sartre devotes a great deal of effort to establishing the impersonal (or “pre-personal”) character of consciousness, which stems from its non-egological structure and results directly from the absence of the I in the transcendental field. According to him, intentional (positional) consciousness typically involves an anonymous and “impersonal” relation to a transcendent object:

When I run after a streetcar, when I look at the time, when I am absorbed in contemplating a portrait, there is no I. […] In fact I am plunged in the world of objects; it is they which constitute the unity of my consciousness; […] but me, I have disappeared; I have annihilated myself. There is no place for me on this level. (Sartre 1936a [1957: 49; 2004: 8])

The tram appears to me in a specific way (as “having-to-be-overtaken”, in this case) that is experienced as its own mode of phenomenalization, and not as a mere relational aspect of its appearing to me . The object presents itself as carrying a set of objective properties that are strictly independent from one’s personal relation to it. The streetcar is experienced as a transcendent object, in a way that obliterates and overrides , so to speak, the subjective features of conscious experience; its “having-to-be-overtaken-ness” does not belong to my subjective experience of the world but to the objective description of the way the world is (see also Sartre 1936a [1957: 56; 2004: 10–11]). When I run after the streetcar, my consciousness is absorbed in the relation to its intentional object, “ the streetcar-having-to-be-overtaken ”, and there is no trace of the “I” in such lived-experience. I do not need to be aware of my intention to take the streetcar, since the object itself appears as having-to-be-overtaken, and the subjective properties of my experience disappear in the intentional relation to the object. They are lived-through without any reference to the experiencing subject (or to the fact that this experience has to be experienced by someone ). This particular feature derives from the diaphanousness of lived-experiences. In a different example of this, Sartre argues that when I perceive Pierre as loathsome, say, I do not perceive my feeling of hatred; rather, Pierre repulses me and I experience him as repulsive (Sartre 1936a [1957: 63–4; 2004: 13]). Repulsiveness constitutes an essential feature of his distinctive mode of appearing, rather than a trait of my feelings towards him. Sartre concludes that reflective statements about one’s Ego cannot be logically derived from non-reflective (“ irréfléchies ”) lived-experiences:

Thus to say “I hate” or “I love” on the occasion of a singular consciousness of attraction or repulsion, is to carry out a veritable passage to the infinite […] Nothing more is needed for the rights of reflection to be singularly limited: it is certain that Pierre repulses me, yet it is and will remain forever doubtful that I hate him. Indeed, this affirmation infinitely exceeds the power of reflection. (Sartre 1936a [1957: 63–4; 2004: 13])

This critique of the powers of reflection forms one important part of Sartre’s argument for the primacy of pre-reflective consciousness over reflective consciousness, which is central to many of the pivotal arguments of Being and Nothingness , as we indicate in the relevant sections below.

For many of his readers, the book on the Imaginary that Sartre published in 1940 constitutes one of the most rigorous and fruitful developments of his Husserl-inspired phenomenological investigations. Along with the The Emotions: Outline of a Theory which was published one year before (Sartre 1939b), Sartre presented this study of imagination as an essay in phenomenological psychology, which drew on his lifetime interest in psychological studies and brought to completion the research on imagination he had undertaken since the very beginning of his philosophical career. With this new essay, Sartre continues to explore the relationship between intentional consciousness and reality by focusing upon the specific case of the intentional relations to the unreal and the fictional, so as to produce an in-depth analysis of “the great ‘irrealizing’ function of consciousness”. Engaging in a detailed discussion with recent psychological research that Sartre juxtaposes with (and against) fine-grained phenomenological descriptions of the structures of imagination, his essay proposes his own theory of the imaginary as the corollary of a specific intentional attitude that orients consciousness towards the unreal.

In a similar fashion to his analysis of the world-shaping powers of emotions (Sartre 1939b), Sartre describes and highlights how imagination presents us with a coherent world, although made of objects that do not precede but result from the imaging capacities of consciousness. “The object as imaged, Sartre claims, is never anything more than the consciousness one has of it” (Sartre 1940 [2004: 15]). Contrary to other modes of consciousness such as perception or memory, which connect us to a world that is essentially one and the same, the objects to which imaginative consciousness connects us belong to imaginary worlds, which may not only be extremely diverse, but also follow their own rules, having their own spatiality and temporality. The island of Thrinacia where Odysseus lands on his way back to Ithaca needs not be located anywhere on our maps nor have existed at a specific time: its mode of existence is that of a fictional object, which possesses its own spatiality and temporality within the imaginary world it belongs to.

Sartre stresses that the intentional dimension of imaging consciousness is essentially characterised by its negativity. The negative act, Sartre writes, is “constitutive of the image” (Sartre 1940 [2004: 183]): an image consciousness is a consciousness of something that is not , whether its object is absent, non-existing, or fictional. When we picture Odysseus sailing back to his native island, Odysseus is given to us “as absent to intuition”. In this sense, Sartre concludes,

one can say that the image has wrapped within it a certain nothingness. […] However lively, appealing, strong the image, it gives its object as not being. (Sartre 1940 [2004: 14])

The irrealizing function of imagination results from this immediate consciousness of the nothingness of its object. Sartre’s essay investigates how imaging consciousness allows us to operate with its objects as if they were present, even though these very objects are given to us as non-existing or absent. This is for instance what happens when we go to the theatre or read a novel:

To be present at a play is to apprehend the characters on the actors, the forest of As You Like It on the cardboard trees. To read is to realize contact with the irreal world on the signs. In this world there are plants, animals, fields, towns, people: initially those mentioned in the book and then a host of others that are not named but are in the background and give this world its depth. (Sartre 1940 [2004: 64])

The irreality of imaginary worlds does not prevent the spectator or reader from projecting herself into this world as if it was real . The acts of imagination can consequently be described as “magical acts” (Sartre 1940 [2004: 125]), similar to incantations with respect to the way they operate, since they are designed to make the object of one’s thought or desire appear in such a way that one can take possession of it.

In the conclusion of his essay, Sartre stresses the philosophical significance of the relationship between imagination and freedom, which are both necessarily involved in our relationship to the world. Imagination, Sartre writes, “is the whole of consciousness as it realizes its freedom” (Sartre 1940 [2004: 186]). Imaging consciousness posits its object as “out of reach” in relation to the world understood as the synthetic totality within which consciousness situates itself. For Sartre, the imaginary creation is only possible if consciousness is not placed “in-the-midst-of-the-world” as one existent among others.

For consciousness to be able to imagine, it must be able to escape from the world by its very nature, it must be able to stand back from the world by its own efforts. In a word, it must be free. (Sartre 1940 [2004: 184])

In that respect, the irrealizing function of imagination allows consciousness to “surpass the real” so as to constitute it as a proper world : “the nihilation of the real is always implied by its constitution as a world”. This capacity of surpassing the real to make it a proper world defines the very notion of “situation” that becomes central in Sartre’s philosophical thought after the publication of the Imaginary . Situations are nothing but “the different immediate modes of apprehension of the real as a world” (Sartre 1940 [2004: 185]). Consciousness’ situation-in-the-world is precisely that which motivates the constitution of any irreal object and accounts for the creation of imaginary worlds—for instance, and perhaps above all, in art:

Every apprehension of the real as a world tends of its own accord to end up with the production of irreal objects since it is always, in a sense, free nihilation of the world and this always from a particular point of view. (Sartre 1940 [2004: 185])

With this conclusion, which prioritises the question of the world over that of reality, Sartre begins to move away from the realist perspective he was initially aiming at when he first discovered phenomenology, so as to make the phenomenological investigation of our “being-in-the-world” (influenced by his careful rereading of Heidegger in the late 30s) his new priority.

Although Sartre never stated it explicitly, his interest in the question of the unreal and imaging consciousness appears to be intimately connected with his general conception of literature and his self-understanding of his own literary production. The concluding remarks of the Imaginary extend the scope of Sartre’s phenomenological analyses of the irrealizing powers of imagination, by applying them to the domain of aesthetics so as to answer the question about the ontological status of works of art. For Sartre, any product of artistic creation—a novel, a painting, a piece of music, or a theatre play—is just as irreal an object as the imaginary world it gives rise to. The irreality of the work of art allows us to experience—though only imaginatively—the world it gives flesh to as an “analogon” of reality. Even a cubist painting, which might not depict nor represent anything, still functions as an analogon, which manifests

an irreal ensemble of new things , of objects that I have never seen nor will ever see but that are nonetheless irreal objects. (Sartre 1940 [2004: 191])

Likewise, the novelist, the poet, the dramatist, constitute irreal objects through verbal analogons.

This original conception of the nature of the work of art dominates Sartre’s critical approach to literature in the many essays he dedicates to the art of the novel. This includes his critical analyses of recent writers’ novels in the 30s—Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Mauriac, etc.—and the publication in the late 40s of his own summative view, What is literature? (Sartre 1948a [1988]). In a series of articles gathered in the first volume of his Situations (1947, Sit. I ), Sartre defends a strong version of literary realism that can, somewhat paradoxically, be read as a consequence of his theory of the irreality of the work of art. If imagination projects the spectator within the imaginary world created by the artist, then the success of the artistic process is proportional to the capacity of the artwork to let the spectator experience it as a reality of its own, giving rise to a full-fledged world. Sartre applies in particular this analysis to novels, which must aim, according to him, at immersing the reader within the fictional world they depict so as to make her experience the events and adventures of the characters as if she was living them in first person. The complete absorption of the reader within the imaginary world created by the novelist must ultimately recreate the particular feel of reality that defines Sartre’s phenomenological kind of literary realism (Renaudie 2017), which became highly influential over the following decades in French literature. The reader must be able to experience the actions of the characters of the novel as if they did not result from the imagination of the novelist, but proceeded from the character’s own freedom—and Sartre goes as far as to claim that this radical “spellbinding” (“envoûtante”, Sartre 1940 [2004: 175])) quality of literary fiction defines the touchstone of the art of the novel (See “François Mauriac and Freedom”, in Sartre Sit. I ).

This original version of literary realism is intrinsically tied to the question of freedom, and opposed to the idea according to which realist literature is expected to provide a mere description of reality as it is . In What is Literature? , Sartre describes the task of the novelist as that of disclosing the world as if it arose from human freedom—rather than from a deterministic chain of causes and consequences. The author’s art consists in obliging her reader “to create what [she] discloses ”, and so to share with the writer the responsibility and freedom involved in the act of literary creation (Sartre 1948a [1988: 61]). In order for the world of the novel to offer its maximum density,

the disclosure-creation by which the reader discovers it must also be an imaginary engagement in the action; in other words, the more disposed one is to change it, the more alive it will be.

The conception of the writer’s engagement that resulted from these analyses constitutes probably the most well-known aspect of Sartre’s relation to literature. The writer only has one topic: freedom.

This analysis of the role of imaginative creations of art can also help us to understand the role of philosophy within his own novels, particularly in Nausea , a novel which Sartre began as he was studying Husserl in Berlin. In this novel Sartre’s pre-phenomenological interest for the irreducibility of contingency intersects with his newly-acquired competences in phenomenological analyses, making Nausea a beautifully illustrated expression of the metaphysical register Sartre gave to Husserl’s conception of intentionality. The feeling of nausea that Roquentin, the main character of Sartre’s novel, famously experienced in a public garden while obsessively watching a chestnut tree, accounts for his sensitivity to the absolute lack of necessity of whatever exists. Sartre understands this radical absence of necessity as the expression of the fundamental contingency of being. Roquentin’s traumatic moment of realisation that there is absolutely no reason for the existence of all that exists illustrates the intuition that motivated Sartre’s philosophical thinking since the very beginning of his intellectual career as a student at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, as Simone de Beauvoir recalls (1981 [1986]). It constitutes the metaphysical background of his interpretation of intentionality, which he would come to develop and systematise in the early dense parts of Being and Nothingness . While the experience of nausea when confronting the contingency of the chestnut tree does not give us conceptual knowledge, it involves a form of non-conceptual ontological awareness that is of a fundamentally different order to, and cannot be derived from, our conceptual understanding and knowledge of brute existence.

4. Being and Nothingness

Being and Nothingness (1943) remains the defining treatise of the existentialist “movement”, along with works from de Beauvoir from this period (e.g., The Ethics of Ambiguity ). We cannot do justice to the entirety of the book here, but we can indicate the broad outlines of the position. In brief, Sartre provides a series of arguments for the necessary freedom of “human reality” (his gloss on Heidegger’s conception of Dasein), based upon an ontological distinction between what he calls being-for-itself ( pour soi ) and being-in-itself ( en soi ), roughly between that which negates and transcends (consciousness) and the "pure plenitude" of objects. That kind of metaphysical position might seem to “beg the question” by assuming what it purports to establish (i.e., radical human freedom). However, Sartre argues that realism and idealism cannot sufficiently account for a wide range of phenomena associated with negation. He also draws on the direct evidence of phenomenological experience (i.e., the experience of anguish). But the argument for his metaphysical picture and human freedom is, on balance, an inference to the best explanation. He contends that his complex metaphysical vision best captures and explains central aspects of human reality.

As the title of the book suggests, nothingness plays a significant role. While Sartre’s concern with nothingness might be a deal-breaker for some, following Rudolph Carnap’s trenchant criticisms of Heidegger’s idea that the “nothing noths/nothings” (depending on translation from the German), Sartre’s account of negation and nothingness (the latter of which is the ostensible ground of the former) is nevertheless philosophically interesting. Sartre does not say much about the genesis of consciousness or the for-itself, other than that it is contingent and arises from “the effort of an in-itself to found itself” (Sartre 1943 [1956: 84]). He describes the appearance of the for-itself as the absolute event, which occurs through being’s attempt “to remove contingency from its being”. Accordingly, the for-itself is radically and inescapably distinct from the in-itself. In particular, it functions primarily through negation, whether in relation to objects, values, meaning, or social facts. According to Sartre this negation is not about any reflective judgement or cognition, but an ontological relation to the world. This ontological interpretation of negation minimises the subjectivist interpretations of his philosophy. The most vivid example he provides to illustrate this pre-reflective negation is the apprehension of Pierre’s absence from a café. Sartre describes Pierre’s absence as pervading the whole café. The café is cast in the metaphorical “shade” of Pierre not being there at the time he had been expected. This experience depends on human expectations, of course. But Sartre argues that if, by contrast, we imagine or reflect that someone else is not present (say the Duke of Wellington, an elephant, etc.), these abstract negative facts are not existentially given in the same manner as our pre-reflective encounter with Pierre’s absence. They are not given as an “objective fact”, as a “component of the real”.

Sartre provides numerous other examples of pre-reflective negation throughout Being and Nothingness . He argues that the apprehension of fragility and destruction are likewise premised on negativity, and any effort to adequately describe these phenomena requires negative concepts, but also that they presuppose more than just negative thoughts and judgements. In regard to destruction, Sartre suggests that there is not less after the storm, just something else (Sartre 1943 [1956: 8]). Generally, we do not need to reflectively judge that a building has been destroyed, but directly see it in terms of that which it is not —the building, say, in its former glory before being wrecked by the storm. Humans introduce the possibility of destruction and fragility into the world, since objectively there is just a change. Sartre’s basic question is: how could we accomplish this unless we are a being by whom nothingness comes into the world, i.e., free? He poses similar arguments in regard to a range of phenomena that present as basic to our modes of inhabiting the world, from bad faith through to anguish. In all of these cases Sartre argues that while we can expressly pose negative judgements, or deliberately ask questions that admit of the possibility of negative reply, or consciously individuate and distinguish objects by reference to the objects which they are not, there is a pre-comprehension of non-being that is the condition of such negative judgements.

Although the for-itself and the in-itself are initially defined very abstractly, the book ultimately comes to say a lot more about the for-itself, even if not much more about the in-itself. The picture of the for-itself and its freedom gradually becomes more “concrete”, reflecting the architectonic of the text, which has more sustained treatments of the body, others, and action, in the second half. Throughout, Sartre gives a series of paradoxical glosses on the nature of the for-itself—i.e., a “being which is what it is not and is not what it is” (Sartre 1943 [1956: 79]). Although this might appear to be a contradiction, Sartre’s claim is that it is the fundamental mode of existence of the for-itself that is future-oriented and does not have a stable identity in the manner of a chair, say, or a pen-knife. Rather, “existence precedes essence”, as he famously remarks in both Being and Nothingness and Existentialism is a Humanism .

In later chapters he develops the basic ontological position in regard to free action. His point is not, of course, to say we are free to do or achieve anything (freedom as power), or even to claim that we are free to “project” anything at all. The for-itself is always in a factical situation. Nonetheless, he asserts that the combination of the motives and ends we aspire to in relation to that facticity depend on an act of negation in relation to the given. As he puts it: “Action necessarily implies as its condition the recognition of a “desideratum”; that is, of an objective lack or again of a negatité” (Sartre 1943 [1956: 433]). Even suffering in-itself is not a sufficient motive to determine particular acts. Rather, it is the apprehension of the revolution as possible (and as desired) which gives to the worker’s suffering its value as motive (Sartre 1943 [1956: 437]). A factual state, even poverty, does not determine consciousness to apprehend it as a lack. No factual state, whatever it may be, can cause consciousness to respond to it in any one way. Rather, we make a choice (usually pre-reflective) about the significance of that factual state for us, and the ends and motives that we adopt in relation to it. We are “condemned” to freedom of this ontological sort, with resulting anguish and responsibility for our individual situation, as well as for more collective situations of racism, oppression, and colonialism. These are the themes for which Sartre became famous, especially after World War 2 and Existentialism is a Humanism .

In Being and Nothingness he provides various examples that are designed to make this quite radical philosophy of freedom plausible, including the hiker who gives in to their fatigue and collapses to the ground. Sartre says that a necessary condition for the hiker to give in to their fatigue—short of fainting—is that their fatigue goes from being experienced as simply part of the background to their activity, with their direct conscious attention focusing on something else (e.g., the scenery, the challenge, competing with a friend, philosophising, etc.), to being the direct focus of their attention and thus becoming a motive for direct recognition of one’s exhaustion and the potential action of collapsing to the ground. Although we are not necessarily reflectively aware of having made such a decision, things could have been otherwise and thus Sartre contends we have made a choice. Despite appearances, however, Sartre insists that his view is not a voluntarist or capricious account of freedom, but one that necessarily involves a situation and a context. His account of situated freedom in the chapter “Freedom and Action” affirms the inability to extricate intentions, ends, motives, and reasons, from the embodied context of the actor. As a synthetic whole, it is not merely freedom of intention or motive (and hence even consciousness) that Sartre affirms. Rather, our freedom is realised only in its projections and actions, and is nothing without such action.

Sartre’s account of bad faith ( mauvaise foi ) is of major interest. It is said to be a phenomenon distinctive of the for-itself, thus warranting ontological treatment. It also feeds into questions to do with self-knowledge (see Moran 2001), as well as serving as the basis for some of his criticisms of racism and colonialism in his later work. His account of bad faith juxtaposes a critique of Freud with its own “depth” interpretive account, “existential psychoanalysis”, which is itself indebted to Freud, as Sartre admits.

We will start with Sartre’s critique of Freud, which is both simple and complex, and features in the early parts of the chapter on bad faith in Being and Nothingness . In short, Freud’s differing meta-psychological pictures (Conscious, Preconscious, Unconscious, or Id, Ego, Superego) are charged with splitting the subject in two (or more) in attempting to provide a mechanistic explanation of bad faith: that is, how there can be a “liar” and a “lied to” duality within a single consciousness. But Sartre accuses Freud of reifying this structure, and rather than adequately explaining the problem of bad faith, he argues that Freud simply transfers the problem to another level where it remains unsolved, thus consisting in a pseudo-explanation (which today might be called a “homuncular fallacy”). Rather than the problem being something that pertains to an embodied subject, and how they might both be aware of something and yet also repress it at the same time, Sartre argues that the early Freudian meta-psychological model transfers the seat of this paradox to the censor: that is, to a functional part of the brain/mind that both knows and does not know. It must know enough in order to efficiently repress, but it also must not know too much or nothing is hidden and the problematic truth is manifest directly to consciousness. Freud’s “explanation” is hence accused of recapitulating the problem of bad faith in an ostensible mechanism that is itself “conscious” in some paradoxical sense. Sartre even provocatively suggests that the practice of psychoanalysis is itself in bad faith, since it treats a part of ourselves as “Id”-like and thereby denies responsibility for it. That is not the end of Sartre’s story, however, because he ultimately wants to revive a version of psychoanalysis that does not pivot around the “unconscious” and these compartmentalised models of the mind. We will come back to that, but it is first necessary to introduce Sartre’s own positive account of bad faith.

While bad faith is inevitable in Sartre’s view, it is also important to recognise that the “germ of its destruction” lies within. This is because bad faith always remains at least partly available to us in our own lived-experience, albeit not in a manner that might be given propositional form in the same way as knowledge of an external object. In short, when I existentially comprehend that my life is dissatisfying, or even reflect on this basis that I have lived an inauthentic life, while I am grasping something about myself (it is given differently to the recognition that others have lived a lie and more likely to induce anxiety), I am nonetheless not strictly equivalent or identical with the “I” that is claimed to be in bad faith (cf. Moran 2001). There is a distanciation involved in coming to this recognition and the potential for self-transformation of a more practical kind, even if this is under-thematised in Being and Nothingness .

Sartre gives many examples of bad faith that remain of interest. His most famous example of bad faith is the café waiter who plays at being a café waiter, and who attempts to institutionalise themselves as this object. While Sartre’s implied criticisms of their manner of inhabiting the world might seem to disparage social roles and affirm an individualism, arguably this is not a fair reading of the details of the text. For Sartre we do have a factical situation, but the claim is that we cannot be wholly reduced to it. As Sartre puts it:

There is no doubt I am in a sense a café waiter—otherwise could I not just as well call myself a diplomat or reporter? But if I am one, this cannot be in the mode of being-in-itself. I am a waiter in the mode of being what I am not . (Sartre 1943 [1956: 60])

In subsequent work, racism becomes emblematic of bad faith, when we reduce the other to some ostensible identity (e.g., Anti-semite and the Jew ).

It is important to recognise that no project of “sincerity”, if that is understood as strictly being what one is, is possible for Sartre given his view of the for-itself. Likewise, in regard to any substantive self-knowledge that might be achieved through direct self-consciousness, our options are limited. On Sartre’s view we cannot look inwards and discover the truth about our identity or our own bad faith through simple introspection (there is literally no-thing to observe). Moreover, when we have a lived experience, and then reflect on ourselves from outside (e.g., third-personally), we are not strictly reducible to that Ego that is so posited. We transcend it. Or, to be more precise, we both are that Ego (just as we are what the Other perceives) and yet are also not reducible to it. This is due to the structure of consciousness and the arguments from Transcendence of the Ego examined in section 2 . In Being and Nothingness , the temporal aspects of this non-coincidence are also emphasised. We are not just our past and our objective attributes in accord with some sort of principle of identity, because we are also our “projects”, and these are intrinsically future oriented.

Nonetheless, Sartre argues that it would be false to conclude that all modes of inhabiting the world are thereby equivalent in terms of “faith” and “bad faith”. Rather, there are what he calls “patterns of bad faith” and he says these are “objective”. Any conduct can be seen from two perspectives—transcendence and facticity, being-for-itself and being-for-others. But it is the exclusive affirmation of one or the others of these (or a motivated and selective oscillation between them) which constitutes bad faith. There is no direct account of good faith in Being and Nothingness , other than the enigmatic footnote at the end of the book that promises an ethics. There are more sustained treatments of authenticity in his Notebooks for an Ethics and in Anti-semite and Jew (see also the entry on authenticity ).

Sartre’s work on inter-subjectivity is often the subject of premature dismissal. The hyperbolic dimension of his writings on the Look of the Other and the pessimism of his chapter on “concrete relations with others”, which is essentially a restatement of the “master-slave” stage of Hegel’s struggle for recognition without the possibility of its overcoming, are sometimes treated as if they were nothing but the product of a certain sort of mind—a kind of adolescent paranoia or hysteria about the Other (see, e.g., Marcuse 1948). What this has meant, however, is that the significance of Sartre’s work on inter-subjectivity, both within phenomenological circles and more broadly in regard to philosophy of mind and social cognition, has been downplayed. Building on the insights of Hegel, Husserl and Heidegger, Sartre proposes a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for any theory of the other, which are far from trivial. In Being and Nothingness , Sartre suggests that various philosophical positions—realism and idealism, and beyond—have been shipwrecked, often unawares, on what he calls the “reef of solipsism”. His own solution to the problem of other minds consists, first and foremost, in his descriptions of being subject to the look of another, and the way in which in such an experience we become a “transcendence transcended”. On his famous description, we are asked to imagine that we are peeping through a keyhole, pre-reflectively immersed and absorbed in the scene on the other side of the door. Maybe we would be nervous engaging in such activities given the socio-cultural associations of being a “Peeping Tom”, but after a period of time we would be given over to the scene with self-reflection and self-awareness limited to merely the minimal (tacit or “non-thetic” in Sartre’s language) understanding that we are not what we are perceiving. Suddenly, though, we hear footsteps, and we have an involuntary apprehension of ourselves as an object in the eyes of another; a “pre-moral” experience of shame; a shudder of recognition that we are the object that the other sees, without room for any sort of inferential theorising or cognising (at least that is manifest to our own consciousness). This ontological shift, Sartre says, has another person as its condition, notwithstanding whether or not one is in error on a particular occasion of such an experience (i.e., the floor creaks but there is no-one actually literally present). While many other phenomenological accounts emphasise empathy or direct perception of mental states (for example, Scheler and Merleau-Ponty), Sartre thereby adds something significant and distinctive to these accounts that focus on our experience of the other person as an object (albeit of a special kind) rather than as a subject. In common with other phenomenologists like Merleau-Ponty and Scheler, Sartre also maintains that it is a mistake to view our relations with the other as one characterised by a radical separation that we can only bridge with inferential reasoning. Any argument by analogy, either to establish the existence of others in general or to particular mental states like anger, is problematic, begging the question and having insufficient warrant.

For Sartre, at least in his early work, our experience of being what he calls a “we subject”—as a co-spectator in a lecture or concert for example, which involves no objectification of the other people we are with—is said to be merely a subjective and psychological phenomenon that does not ground our understanding and knowledge of others ontologically (Sartre 1943 [1956: 413–5]). Originally, human relations are typified by dyadic mode of conflict best captured in the look of the other, and the sort of scenario concerning the key-hole we just considered above. Given that we also do not grasp a plural look, for Sartre, this means that social life is fundamentally an attempt to control the impact of the look upon us, either by anticipating it in advance and attempting to invalidate that perspective (sadism) or by anticipating it and attempting to embrace that solicited perspective when it comes (masochism). In Sartre’s words:

It is useless for human reality to seek to escape this dilemma: one must either transcend the Other or allow oneself to be transcended by him. The essence of the relations between consciousness is not the Mitsein (being-with); it is conflict. (Sartre 1943 [1956: 429])

Sartre’s radical criticism of Freud’s theory of the unconscious is not his last word on psychoanalysis. In the last chapters of Being and Nothingness , Sartre presents his own conception of an existential psychoanalysis, drawing on some insights from his attempt to account for Emperor Wilhelm II as a “human-reality” in the 14 th notebook from his War Diaries (Sartre 1983b [1984]). This existential version of psychoanalysis is claimed to be compatible with Sartre’s rejection of the unconscious, and is expected to achieve a “psychoanalysis of consciousness” (Moati 2020: 219), allowing us to understand one’s existence in light of their fundamental free choice of themselves.

The very idea of a psychoanalysis oriented towards the study of consciousness rather than the unconscious seems paradoxical—a paradox increased by Sartre’s efforts to highlight the fundamental differences that oppose his own version of psychoanalysis to Freud’s. Sartre contends that Freud’s “empirical” psychoanalysis

is based on the hypothesis of the existence of an unconscious psyche, which on principle escapes the intuition of the subject.

By contrast, Sartre’s own existential psychoanalysis aims to remain faithful to one of the earliest claims of Husserl’s phenomenology: that all psychic acts are “coextensive with consciousness” (Sartre 1943 [1956: 570]). For Sartre, however, the basic motivation for rejecting Freud’s hypothesis is less an inheritance of Brentano’s descriptive psychology (as was the case for Husserl) than a consequence of Sartre’s fundamental critique of determinism, applied to the naturalist presuppositions of empirical psychoanalysis and the particular kind of determinism that it involves. In agreement with Freud, Sartre holds that psychic life remains inevitably “opaque” and at least somewhat impenetrable to us. He also stresses that the philosophical understanding of human reality requires a method for investigating the meaning of psychic facts. But Sartre denies that the methods and causal laws of the natural sciences are of any help in that respect. The human psyche cannot be fully analysed and explained as a mere result of external constraints acting like physical forces or natural causes. The for-itself, being always what it is not and not what it is, remains free whatever the external and social constraints. Sartre is consequently bound to reject any emphasis on the causal impact of the past upon the present, which he argues is the basic methodological framework of empirical psychoanalysis. That does not mean that past psychic or physical facts have no impact on one’s existence whatsoever. Rather, Sartre contends that the impact of past events is determined in relation to one’s present choice, and understood as the consequence of the power invested in this free choice. As he puts it:

Since the force of compulsion in my past is borrowed from my free, reflecting choice and from the very power which this choice has given itself, it is impossible to determine a priori the compelling power of a past. (Sartre 1943 [1956: 503])

Past events bear no other meaning than the one given by a subject, in agreement with the free project that orients his or her existence towards the future. Conversely, determinist explanations that construe one’s present as a mere consequence of the past proceed from a kind of self-delusion that operates by concealing one’s free project, and thus contributes to the obliteration of responsibility. Sartre hence seeks to redefine the scope of psychoanalysis: rather than a proper explanation of human behaviour that relies on the identification of the laws of its causation, psychoanalysis consists in understanding the meaning of our conducts in light of one’s project of existence and free choice. One might wonder, then, why we need any such psychoanalysis, if the existential project that constitutes its object is freely chosen by the subject. Sartre addresses this objection in Being and Nothingness , claiming that

if the fundamental project is fully experienced by the subject and hence wholly conscious, that certainly does not mean that it must by the same token be known by him; quite the contrary. (Sartre 1943 [1956: 570])

What Freud calls the unconscious must be redescribed as the paradoxical entanglement of a “total absence of knowledge” combined with a “true understanding” ( réelle comprehension ) of oneself (1972, Sit. IX : 111). The legitimacy of Sartre’s existential psychoanalysis of consciousness lies in its ability to unveil the original project according to which one chooses (more or less obscurely) to develop the fundamental orientations of their existence. According to Sartre, analysing a human subject and understanding the meaning that orients their existence as a whole requires that we grasp the specific kind of unity that lies behind their various attitudes and conducts. This unity can only appear once we discover the synthetic principle of unification or “totalization” ( totalisation ) that commands the whole of their behaviours. Sartre understands this totalization as an an-going process that covers the entire course of one’s existence, a process which is constantly reassumed so as to integrate the new developments of this existence. For this reason, this never ending process of totalization cannot be fully self-conscious or the object of reflective self-knowledge. The synthetic principle that makes this totalization possible is identified by Sartre in terms of fundamental choice: existential psychoanalysis describes human subjects as synthetic totalities in which every attitude, conduct, or behaviour finds its meaning in relation to the unity of a primary choice, which all of the subject’s behaviour expresses in its own way.

All human behaviour can thus be described as a secondary particularisation of a fundamental project which expresses the subject’s free choice, and conditions the intelligibility of their actions. On the basis of his diagnosis of Baudelaire’s existential project, for instance, Sartre goes as far as to claim that he is “prepared to wager that he preferred meats cooked in sauces to grills, preserves to fresh vegetables” (Sartre 1947a [1967: 113]). Sartre legitimates such a daring statement by showing its logical connection to Baudelaire’s irresistible hatred for nature, from which his gastronomic preferences must derive, and which Sartre identifies as the expression of the initial free choice of himself that commands the whole of the French poète maudit ’s existence. In Sartre’s words:

He chose to exist for himself as he was for others. He wanted his freedom to appear to himself like a “nature”; and he wanted this “nature” which others discovered in him to appear to them like the very emanation of his freedom. From that point everything becomes clear. […] We should look in vain for a single circumstance for which he was not fully and consciously responsible. Every event was a reflection of that indecomposable totality which he was from the first to the last day of his life (Sartre 1947a [1967: 191–192]).

Baudelaire’s choice of himself both accounts for the subject’s freedom (insofar as it has been freely accepted as the subject’s own project of existence) and exerts a constraint on particular behaviours and attitudes towards the world, so that he is bound to act and behave in a way that must be compatible with that choice. Although absolutely free, such an initial choice takes the shape and the meaning of an inescapable and relentless destiny —a destiny in which one’s sense of freedom and their inability to act in any other way than they actually did come to merge perfectly: “the free choice which a man makes of himself is completely identified with what is called his destiny” (Sartre 1947a [1967: 192]).