- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Conflict Studies

- Development

- Environment

- Foreign Policy

- Human Rights

- International Law

- Organization

- International Relations Theory

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Geography

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Sexuality and Gender

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Security Studies

- Back to results

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Geographic perspectives on world-systems theory.

- Colin Flint Colin Flint Department of Political Science, Utah State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.196

- Published in print: 01 March 2010

- Published online: 22 December 2017

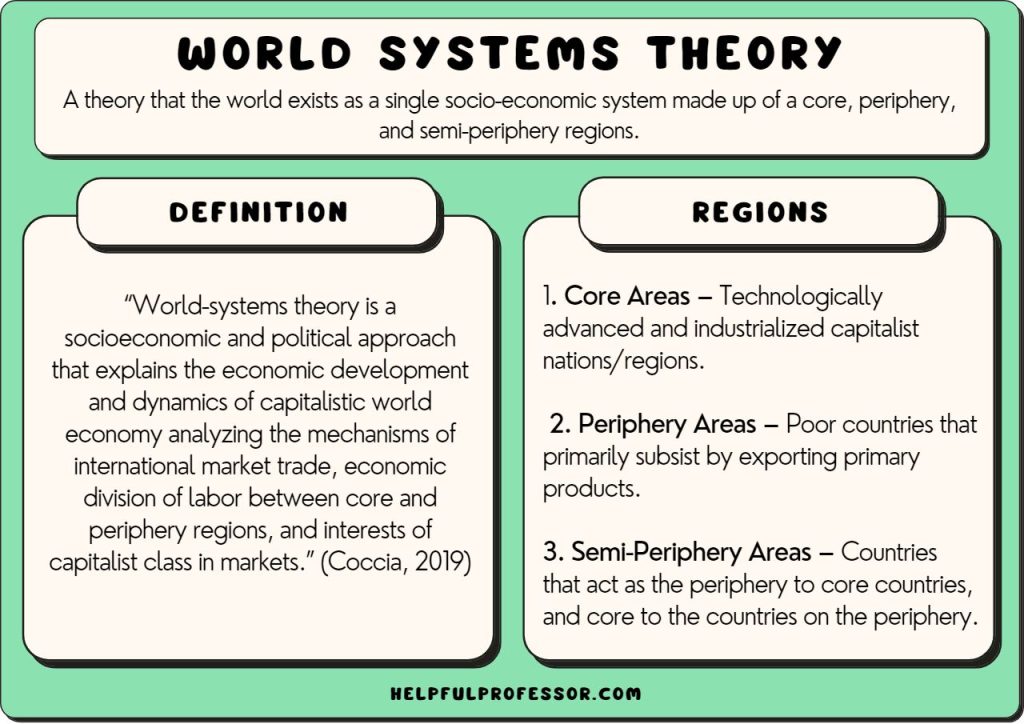

World-systems theory is a multidisciplinary, macro-scale approach to world history and social change which emphasizes the world-system as the primary (but not exclusive) unit of social analysis. “World-system” refers to the inter-regional and transnational division of labor, which divides the world into core countries, semi-periphery countries, and the periphery countries. Though intrinsically geographical, world-systems perspectives did not receive geographers’ attention until the 1980s, mostly in economic and political geography. Nevertheless, geographers have made important contributions in shaping world-systems perspectives through theoretical development and critique, particularly in the understanding of urban processes, states, and geopolitics. The world-systems theory can be considered as a sub-discipline of the study of political geography. Although sharing many of the theories, methods, and interests as human geography, political geography has a particular interest in territory, the state, power, and boundaries (including borders), across a range of scales from the body to the planet. Political geography has extended the scope of traditional political science approaches by acknowledging that the exercise of power is not restricted to states and bureaucracies, but is part of everyday life. This has resulted in the concerns of political geography increasingly overlapping with those of other sub-disciplines such as economic geography, and, particularly, with those of social and cultural geography in relation to the study of the politics of place.

- world-systems theory

- political geography

- social analysis

- urban processes

- geopolitics

- human geography

- economic geography

- cultural geography

Introduction

World-systems theory is a body of knowledge built upon the foundations of the Annales school of history, a perspective that emphasizes the importance of broad social structures spanning long periods of history and their impact upon everyday life (Braudel 1973 ; 1984 ). The Braudelian perspective was adapted by Immanuel Wallerstein in a series of theoretical papers in the 1970s, complemented by an ambitious multi-volume history of the capitalist world-economy. Wallerstein’s publications were supported by the creation of the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations at SUNY-Binghamton in 1976 , and the establishment of the journal Review in 1977 . World-systems theory transcended disciplinary boundaries, and identified the scale of social change as the historic social system. Wallerstein’s histories and theoretical contributions focused upon the expansion of the capitalist world-economy from its origins in the mid-1400s. Geographers were initially attracted to world-systems theory because it offered a theoretical framework in a discipline that was, at the time, largely atheoretical. In addition, world-systems theory seemingly promoted geographical questions in two ways: space and scale. Space was integral to the theory in the identification of unequal economic relationships that created patterns of global inequality, or a new theoretical way to explain “underdevelopment.” The question of scale was made explicit by the work of Peter Taylor and his situation of local and national political events within the overarching structure of the capitalist world-economy.

These two avenues to geography were addressed implicitly and, at the outset, explicitly by human geographers in the early 1980s. The theoretical contribution was seized upon and promoted understandings of the mutual construction of politics and geography: or the understanding that political actions necessarily constructed spaces and spaces mediated political actions. For example, nation-states are politically constructed spaces. Another example would be the way in which spaces of formal or informal imperialism partially define the forms of political activity that occur within them. As human geography became more theoretical, beginning in the 1980s, the mutual construction of space and society became axiomatic, despite variations in theoretical frameworks. The main issue explored in this essay is how the initial introduction of politically constructed spaces by world-systems theory became to be critiqued as overly structural.

World-systems theory (Wallerstein 2004 ) was integral to the revival of political geography in the 1970s and 1980s (Taylor 1981a ; 1982 ; Shelley and Flint 2000 ). However, over time the theoretical development of the subdiscipline prioritized critiques of structural models resulting in a diminished role for world-systems theory in framing political geographic analysis (Cox et al. 2008a ). Contemporary political geography has become dominated by approaches that emphasize contingency, agency, and the scale of the everyday rather than the structures, historical processes, and macro-change that dominate world-systems theory. Ironically, the current emphasis upon the mutual social construction of politics and geography is also the essence of the frameworks adopted by Peter Taylor in his development of a world-systems theory political geography. The key difference is that world-systems theory starts with a structural perspective rather than an immediate and actor-based view.

This essay discusses the role of world-systems theory in catalyzing political geography and the subsequent critiques toward the former’s structural focus. Developing an organizing thread that highlights the socially constructed geographies in the world-systems theory framework, the roles of scale, hegemony, political actors, states, and world-cities are discussed in detail. The essay concludes with a consideration of the continued relevance of a world-systems political geography as a heuristic device despite its recognized limitations as a theoretical framework. The focus of this essay is restricted in two ways. First, it emphasizes Anglo-American geographic scholarship, though this is a true reflection of the center of gravity of the world-systems approach to geography. Interestingly, the perspective gained little currency in French or German academic geography or in other parts of the world. Second, the essay addresses topics that are of most interest to international studies scholars and, simultaneously, derived from the scholarship of Peter Taylor; the intellectual driving force behind the world-systems revitalization of political geography.

World-Systems Theory and the Resurgence of Political Geography

The contemporary vibrancy of political geography cannot be doubted. The very presence of the subdiscipline in the International Studies Association Compendium is testimony to its visibility, as are the slew of volumes synthesizing contemporary research (for example see Agnew et al. 2007 ; Cox et al. 2008b ), and the strength of the Political Geography and Geopolitics research journals. However, it was only quite recently that the picture was much bleaker. The oft-quoted lament of political geography being a “moribund backwater” (Berry 1969 ) is a pointed but accurate reflection of the intellectual irrelevance of the subdiscipline after World War II. Political geography in the 1950s was framed by functional theories of the state that left no room for contested politics and their role in constructing space (Hartshorne 1950 ). The resurgence of political geography came in the 1980s, and much has been written about the transition and subsequent vitality (Johnston 2001 ).

The point I wish to stress here is that world-systems theory played a significant role in the resurgence of political geography. For the first few years of the renewed interest in political geography, world-systems theory was a central organizing framework, either explicitly or implicitly. The revival of political geography was sparked by interlinked changes in academia and society. Human geographers had become frustrated with the blandness and lack of social processes and structure in the quantitative studies that had led the field from about the 1960s in the discipline’s “Quantitative Revolution” (Johnston and Sidaway 2004 ). Geographers, along with other academics, were taking a “radical turn” through the application of Marxist approaches (Harvey 1973 ). Also, the social turmoil of inner-city riots and the opposition to the Vietnam War were imposing upon human geographers the need to mobilize theoretical frameworks that could inform real-world conflicts (Flint 1999 ). The time was ripe for the escape from the apolitical, functional, and state-centric restrictions of postwar political geography.

Scholars such as Kevin Cox ( 1973 ) and David Harvey ( 1973 ) focused upon adding a geographic perspective to the works of Karl Marx and contemporary interpretations of his texts. On the other hand, Peter Taylor defined another pathway for political geography, one that was informed by the writings of Immanuel Wallerstein and the Annales school. The appeal of world-systems theory for Taylor was not only its radical agenda, but its role as a framework that enabled a new form of political geography (Taylor 1982 ). First, world-systems theory provoked discussion of a scale other than the state through the concept of the historical social system, specifically the capitalist world-economy. Second, the concepts of core, periphery, and semi-periphery promoted inclusion of the traditional geographic concern of areal differentiation (Terlouw 1992 ; Dezzani 2001 ).

World-systems theory enabled geographers to address the global scale again, something that had been difficult in the wake of tainted prewar geopolitical approaches (Dodds and Atkinson 2000 ). It also provided a sense of process to political geography. The dynamics of the capitalist world-economy, through the application of the concept of Kondratieff waves, were identified as the driver of political actions (Taylor 1985 ; Flint and Taylor 2007 ). Kondratieff waves are recurring fifty year long cycles comprising a period of global economic growth and a following period of stagnation and restructuring. The periods of growth are related to the adoption of new economic innovations and the periods of stagnation exhibit intensified politics of redistribution and interstate and interfirm competition. The result was a political-economic logic for political geography that situated political actions and events within the space–time context of the dynamics of Kondratieff waves and position within the core–periphery hierarchy. An important component of this perspective was that states were one form of political actor, or institution, rather than the raison d’être of the discipline, as they had been in the functionalist theories of the 1950s.

Taylor promoted a political geography perspective on world-systems theory through a series of academic articles, discussed below, as well as his seminal textbook, Political Geography (Taylor 1985 ; Flint and Taylor 2007 ). In addition, initial work on political geography was often, though not exclusively, framed by world-systems theory. For example, the geography of violence and premature death (Johnston et al. 1987 , and updated by van der Wusten 2005 ) and elections were analyzed through a world-systems perspective (Taylor 1986 ; 1991a ). Furthermore, the establishment of the resurgent subdiscipline’s new flagship journal, Political Geography , in 1982 contained a research agenda written by the editorial board that included the language of the world-systems perspective. Without doubt, world-systems theory was an essential, though not the only, catalyst in the regeneration of political geography, with Peter Taylor the foremost contributor.

The Resurgence of Political Geography and World-Systems Theory

Political geography’s resurgence further developed through engagement with a variety of different philosophical and theoretical perspectives. Contemporary political geography engages feminist and queer theories, as well as a host of perspectives, such as actor-network theory, that fall under the broad umbrellas of postmodernism and poststructuralism (Agnew et al. 2007 ). Not only has this displaced world-systems theory from the core of the subdiscipline’s theoretical framework, but it has encouraged an active critique of the tenets of a world-systems informed political geography. Three avenues of critique will be discussed below: structural determinism; the identification of geopolitical agents; and focus upon representation in critical geopolitics (Kuus 2009 ).

The space–time matrix outlined by Taylor ( 1985 ) became symptomatic of wariness with a theoretical perspective that was labeled as structurally deterministic. Despite the valiant attempts of Peet ( 1998 ) to explain the complexity and contingency of structures, and Sayer’s ( 1992 ) attempt to define philosophical realism as the appropriate framework for geography, the disapproval of structural determinism became the rallying call of a second wave of political geographers of a variety of stripes. World-systems theory was a particularly easy target because of the prominence of Kondratieff waves in the framework, and the rigid timing, and hence classification, of developments and cycles within repeating twenty-five year periods. Furthermore, the classification of political events such as wars (Johnston et al. 1987 ) and elections (Taylor 1986 ) depending upon their location in the core–periphery hierarchy gave apparently little room for the increasing focus on political contestation and contingency.

A related critique stemmed from Skocpol’s ( 1977 ) argument that world-systems theory, and by extension related political geographies, had marginalized the agency of the state. Despite the irony that it was the recognition of political structures other than the state that was world-systems theory’s appeal to political geography, critiques such as Skocpol’s developed into a stance that world-systems theory drew attention away from actors and agency. Augmenting the critique of structural determinism, political geographers developed humanistic, phenomenological, and feminist approaches to emphasize a host of geopolitical actors (Johnston and Sidaway 2004 ). The new focus on the multiple identities and contingencies of geopolitical actors jarred with the world-systems identification of just four key institutions (households, states, classes, and race/ethnicity) and what could be interpreted as their functional roles (Wallerstein 1984 ). Ironically, the attempt to rescue geography from its postwar functionalist rut through the application of world-systems resulted in a critique of structurally defined functionalism, though at least a healthy dose of theory had been added.

The third basis for the marginalization of world-systems theory was the “representational turn” of human geography. Launching from the work of Foucault and the concept of discourse, the representation of geopolitics, rather than an analysis of events themselves, came to dominate the sphere of political geography interested in international relations (Ó Tuathail 1996 ). Such an approach rejected “meta-narratives” such as those provided by world-systems theory, and instead emphasized the deconstruction of existing texts.

In combination, the three avenues of critique led to the wane of world-system theory’s influence upon political geography. Focus upon agency and representation, and the broader emphasis upon social constructivism and contingency were dramatically opposed, according to the consensus of opinion, to the axioms of world-systems theory (Harvey 1985 ; Agnew 2005 ). Indeed, what had once been a fertile organizing framework, the space–time matrix, became identified as a deterministic straitjacket. The temporal dynamics of Kondratieff waves and the ready resort to a broad areal definition of core and periphery made for easy, and to a large degree justifiable, allegations of determinism. However, as I hope to show in the remainder of this essay, much of the political geographic application of world-systems theory was social constructivist in nature, sensitive to the complexity of geopolitical actors, and aware of contingency.

World-Systems Theory and Political Scales

From the outset of his engagement with world-systems theory Peter Taylor made geographic scale the centerpiece of political geography (Taylor 1981b ). His seminal work arguably positioned the politics of the social construction of scale as the core process of the resurgent subdiscipline. However, the further stages of the resurgence developed a critique of Taylor’s scalar framework including what have become unquestioned interpretations of the “reified” or “preexisting” nature of Taylor’s scales (Marston 2000 ). As I will show, these critiques miss the point of the framework and political processes Taylor was highlighting. Taylor’s scales are socially constructed, but in the tradition of world-systems theory the historical span is grand and beyond the immediacy that dominates contemporary political geography.

Taylor’s ( 1981b ) scales of political geography, with their cryptic but meaningful labels, are the local scale (the scale of experience), the nation-state scale (the scale of ideology), and the global scale (the scale of reality). The local scale is envisioned as the everyday setting of life, or the geographic situation or place in which events occur and life is experienced. The definition of this scale reflects the perceived importance of the politics of place (Agnew 1987 ), recognizing that places filter information and mediate possible political actions. More provocatively, the global scale was labeled the scale of reality to reflect the structural emphasis of world-systems theory. The extent of the social system equates to the geographic scope of the capitalist world-economy (global since the end of the 1800s). Hence, the geographic scope of political and economic processes is traced, ultimately, to the global scale. However, there is also a political motivation to call the global scale “reality.” From a Marxist position, acts of anti-systemic politics should target the scale at which economic processes operate. If, as world-systems theory claims, the scope of economics is global then political movements should target the global too.

The scalar mismatch between the global scope of economic processes and the state focus of political action is behind Taylor’s labeling of the state as the scale of ideology. Politics has, according to Taylor ( 1987 ; 1991b ), become trapped at a scale that limits transformational possibilities. The scale of the state is ideologically dominant as it has become to be understood as the necessary institution to control if political aims are to be achieved. However, Taylor questions this dominant argument and sees the identification of the state scale as the key political target as an ideological hoax. Anti-systemic movements have been sidetracked into seeking control of a scale other than the one at which economic processes ultimately operate. For example, the “socialist” policies of North Korea are seen as a nuisance rather than a challenge to the capitalist world-economy. Also, the anti-systemic politics of international Bolshevism that led to the Russian revolution and the establishment of the Soviet Union quickly became restricted under the heading of “socialism in one state” (Taylor 1992 ).

Underlying all these definitions is an implicit sense that the scales of the capitalist world-economy are socially constructed, though Taylor did not explicitly use this language as it only came into vogue later. The global scale, synonymous with the scope of the capitalist world-economy, is the product of the myriad actions of individuals, firms, households, states, etc. (though admittedly world-systems theorists lay themselves open to charges of structural determinism by not outlining the structure–agent interactions). In fact, it may be argued that key agents at the global scale, such as multinational companies and global institutions (e.g., the UN) are critically ignored. Most importantly, a particular political geography has been constructed in which multiple political units (states) exist within the scope of a single economy. Such a geographic mismatch between political control and the scope of economic processes is unique to the capitalist world-economy (Flint and Taylor 2007 :12). In previous historical social systems (mini-systems and world-empires) the extent of political and economic processes was the same.

The identification of political geographic scales was a key contribution to a burgeoning political geography. The three-scales framework offered a means to contextualize or situate political behavior within broader processes. However, the structural emphasis of this framework led to subsequent theoretical critique (Marston 2000 ). Taylor’s three scales were deemed too structurally deterministic and inadequate tools to analyze the complexity of political agency. Instead of seeing political behavior as a product of the processes of global capital accumulation, subsequent theorists of scale saw political scales as being constructed from the bottom up as contingent strategies by political actors responding to social and cultural situations rather than just economic ones. The economic and structural functionalism of world-systems theory went out of vogue.

The critique of Taylor’s three scales was understandable and constructive on the whole, but failed to address the macro-analysis of social construction that was at the heart of the framework. Rather than seeing the scales as a means to classify political behavior within places solely in terms of the ups and downs of the capitalist world-economy, the framework defined the elements of a social system that separated the scale of political action (the state) from the scale of economic activity (the world-economy). The structural and functionalist elements of this insight undermined the key implications that this scalar separation had for understanding political agency.

The connection between global structures and individual and state behavior is illustrated in theories of hegemony based upon world-systems theory. The specific study of hegemony illustrates how a world-systems framework has renewed the approach to the longstanding topic of geopolitics. Specifically, world-systems theory has been used to situate classical geopolitical theorists as well as state policies and everyday economic and social practices in broader processes.

Contemporary political geography has a complicated relationship with the topic of geopolitics (Dodds and Atkinson 2000 ). Geographers have used world-systems theory in the subdiscipline’s project to situate classical geopolitical theories in order to make sense of the content within particular geohistorical contexts. This approach has allowed the theories of Sir Halford Mackinder and General Karl Haushofer , for example, to be understood as perspectives and agendas from particular countries in particular geopolitical situations. The theoretical steps toward this analysis were built from a structural focus on Kondratieff waves as the economic pulse of the capitalist world-economy to include shifts in general economic orientations (e.g., free trade versus protectionism) and, finally, specific policies. Hegemony, or the process of the rise and fall of one dominant state in the capitalist world-economy, was the overarching concept that connected these questions.

The political geography of Kondratieff waves and the related space–time matrix has specific explanatory value with regard to hegemonic powers, and is of particular benefit in understanding hegemony as a process (Flint and Taylor 2007 :52–7). The economic innovations that drive new Kondratieff waves have been geographically clustered. Or, to put it another way, they have been captured within the borders of one state. Over time, that state has been able to utilize relative monopoly of that innovation to generate an economic foundation that has launched its rise to power. A sequential domination in the spheres of production, trade, and finance was identified by Wallerstein ( 1984 ) as the basis for hegemony. The geographic emphasis, or contribution, is to point out that the foundation is an economic geography of innovation, initially, and subsequently a political geography of attempting to retain location of the innovation within the borders of one state, to trump competitors and imitators.

The simple recognition of the geography of economic innovation within Kondratieff waves was exploited to create what Taylor called the paired-Kondratieff model of hegemony emphasizing the political–economic dynamics of hegemony (Flint and Taylor 2007 :54). The meta-geography of one world-economy and multiple territorial states interacts with the rather anarchic processes of economic innovation and competition to establish a pattern of trade policies. Simply, states that are growing new industries will be protectionist to nurture this base, especially in the face of stronger economies. However, if the new industries successfully form the basis for a new hegemonic power, the hegemonic state will advocate a global regime of free trade so as to exploit its dominance in global production and reap the rewards. If successful, the hegemonic state’s trade dominance will lead to its financial domination. However, the free-trade regime facilitates competition from other states that are able to copy the initial innovations, and often improve upon them (US cars and the later wave of Japanese brands being a good example). The outcome is a decline in economic superiority that will result in a return to protectionist policies as the hegemonic state tries to retain economic strength in the face of competition.

The paired-Kondratieff model is an application of world-systems theory that remains open to challenges of structural determinism. Indeed, the agency of governments, businesses, and social movements in creating free-trade or protectionist regimes is absent from this model. The benefit of the model is a contextualization of individual and group activities. It situates policy debates about trade, for example, within the structural setting of a country’s hegemonic rise and fall. Furthermore, the model “places” geopolitical theorists within global dynamics of hegemonic competition. For example, Sir Halford Mackinder ’s geopolitical theory, written by a member of the ruling elite of a declining hegemonic power, gave priority to a protectionist imperial bloc that reflects the expectations of the paired-Kondratieff model (Flint and Taylor 2007 :57–9). In a similar fashion, the geopolitics of economic relations advocated by Isaiah Bowman reflects the expectations of a rising hegemonic power’s construction of a global free-trade regime.

Taylor’s ( 1990 ) Britain and the Cold War , a study of the political debates within Great Britain at the end of World War II, was a detailed attempt to situate geopolitical decision making within the context of global dynamics derived from a world-systems analysis understanding of hegemony. Taylor begins this book with a structural viewpoint. In aggregation, the foreign policy calculations of individual countries, called geopolitical codes, create a relatively permanent global structure, called a geopolitical world order. The Cold War is identified as a geopolitical world order in which identification of allies and enemies, territorial spheres of influence, and the means of conflict are understood and practiced for a period of time. Though stable for a few decades, geopolitical world orders unravel in what are called geopolitical transitions. For example, the speed with which the Soviet Union and its satellite states changed from being intractable enemies of the West to allies and member of NATO and the European Union was dramatic.

The timing of geopolitical transitions and the form and life span of geopolitical world orders was related to the process of hegemonic rise and fall. The Cold War geopolitical world order was a manifestation of the United States’ incomplete hegemonic power as its role remained contested by the Soviet Union. To maintain the coherence of the cyclical interpretation, the end of the Cold War is interpreted as the inability of the US to maintain its hegemonic regime. The Cold War is seen as part of the geographical organization that underpinned US hegemony, so its termination is interpreted as a manifestation of its decline in power. The contribution of Britain and the Cold War was the discussion of domestic politics, especially debates within Britain’s Labour Party, which defined the role the country would play in the geopolitical world order of US hegemony. Instead of being deterministic, Taylor posits options that Britain faced in defining its geopolitical code. The decision to ally with the United States in an anti-Communist front was made after intense and dramatic debate within the political elite. Though the options of political actors were constrained by the structural setting of British hegemonic decline, US hegemonic rise, and Soviet challenge, the content of Britain’s geopolitical code was a matter of choice. The contribution of the book is that the choice is best understood within the context set by the structural dynamics.

Taylor’s study of hegemony continued with the publication of two related books, The Way the Modern World Works ( 1996 ) and Modernities ( 1998 ). These studies discuss the role of hegemonic powers identified in shaping the economic and social practices of everyday life in the capitalist world economy. The three hegemonic states and the related years of maximum influence and power were The Netherlands (mid-1600s), Great Britain (mid-1800s), and the United States (mid-1900s). Taylor argues that each of these states defined what it meant to be modern through their innovation of economic practices, such as the British factory system, social practices like US suburbia, and culture, e.g., the art of Rembrandt. For the period of US hegemony, the innovative Fordist system produced consumer durables, including automobiles, and created the modern social landscape of the suburb, which was broadcast across the globe in Hollywood and television images of the “good life.” To be modern required an emulation of hegemonic practices, dubbed the “prime modernity” (Taylor 1998 ), which helped diffuse US norms and practices across the globe, though not in an uncontested manner (Flint 2001b ). In an echo of the Braudelian perspective that launched world-systems analysis (Braudel 1973 ; 1984 ), Taylor’s work on hegemonic modernities requires consideration of normal everyday practices and the manner in which they create and maintain broader structures. In this case, the practices of suburban life are both the product and building blocks of US hegemony within the capitalist world-economy. Taylor’s analysis of modernities also highlighted the place-specific setting of these everyday activities: Amsterdam, for example, was a “laboratory” for modern practices with people from all over the world, including Peter the Great, traveling to the place that epitomized what it meant to be modern.

Taylor and other geographers have not just used the concept of hegemony to look back at past political geographies. The United States has been identified as “the last of the hegemons” (Taylor 1993 ; Flint 2001c ; Wallerstein 2003 ) in an argument that suggests that the processes of globalization established within the period of US hegemony have so undermined the autonomy and power of sovereign states relative to global economic processes that in the future no one state will be able to capture the economic power that is the foundation of hegemony. Simply, the argument states that US hegemony has deterritorialized politics and economics to such an extent that a state could no longer territorialize power to establish itself as hegemony. However, this interpretation is countered by the concept of financialization (Arrighi 1994 ), which argues periods of financial flows (that we have labeled “globalization”) were common in the final phases of previous hegemonic powers. According to Arrighi, the deterritorialization we are experiencing now is a manifestation of the decline of the contemporary hegemonic power, the US, rather than the erasure of the possibility of future hegemonic powers.

There is one aspect of this debate that is worth further consideration. The ideology of US hegemony is “the American dream,” a story of how everyone can share the good life if they practice the right (hegemonic) rules and norms. This was a radical shift from the ideology of Britain’s preceding hegemony, which was built upon a rigid class-based division of labor and differential possibilities for consumption. British culture is devoid of the “self-made man” stories that are a staple diet in the US. However, the structural necessity of the core–periphery hierarchy of the capitalist world-economy, and the ecological impossibility of our planet sustaining the consumption levels associated with US suburbia, suggests that maybe a new hegemony is impossible as it cannot supersede the promises of a new modernity made by the US. Alternatively, if there is a new modernity defined by a new hegemonic power it might have the tough task of proclaiming who should have (and have not) the material benefits of the capitalist world-economy. The geography of that hegemonic regime would be one that purposefully demarcated social and territorial settings of inclusion and exclusion.

The concept of prime modernity connected the everyday and mundane practices associated with, for example, suburbia with interstate competition and the long-term processes of hegemony. Hegemony became a process involving a number of geopolitical actors, from suburban households to powerful states. Hence, we turn to another contribution of a world-systems political geography, the identification of multiple geopolitical actors.

Geopolitical Actors

Contemporary political geography has emerged strongly from the poststructuralist turn in the social sciences. Poststructuralism catalyzed human geographers’ move away from a focus upon the state as both unit of analysis and key actor. Political geographers, especially, faced a legacy of state-centric analysis that had naturalized the state as an autonomous and unitary actor (Kuus and Agnew 2008 ). From the very outset, world-systems theory was driven by the recognition that the state was not the ultimately meaningful unit of analysis (Wallerstein 1979 ). Most social science equated the state with society in a noncritical manner (Wallerstein 1991 ). World-systems theory conceptualized the basic unit of analysis, or the unit of social change, as the historical social system: mini-systems, world-empires, and the capitalist world-economy. The modern state is one of four key institutions within the capitalist world-economy. The state becomes a socially constructed institution within a broader social structure: it is an element of social change rather than a synonym for society.

The four key institutions of the capitalist world-economy are states, households, classes, and “peoples” (the latter comprising races, nations, and ethnicities). Each of the institutions reflects the manifestation of a different sphere of politics in the capitalist world-economy, though of course they are tightly related. A political geography of the capitalist world-economy demands an understanding of the multiple politics of the multiplicity of actors in the system. In other words, there is an opportunity to explore a nonstate-centric and multi-actor politics within the capitalist world-economy. On the other hand, a critique of the world-systems approach is its definition of these institutions, and their associated politics, in a functionalist and deterministic manner. This important critique will be addressed after discussing the usefulness of the institutional politics framework.

The four institutions of the capitalist world-economy allow for the conceptualization of fourteen political geographies (Taylor 1991c ). First, there are four intra-institutional politics:

Intrastate politics, or competition over the control of government.

Intra-people politics, manifesting themselves as the politics of defining goals and techniques (for example, regional autonomy versus national independence).

Intra-class politics is also a matter of strategy (such as revolution versus reform).

Intra-household politics manifests itself in gender and generational politics and is highlighted by feminist analysis.

Second, there are four inter-institutional politics:

Inter-state politics, or foreign policy.

Inter-people politics, or racialism and nationalism.

Inter-class politics, or the focus of Marxist scholarship and politics.

Inter-household politics, manifest in local politics over access to resources and services.

Third, are the six politics between institutions:

State–people politics, or more commonly known as the construction and maintenance of nation-states.

State–class politics, for example the manner in which political parties have evolved to manage different societal claims to the control of the state apparatus.

State–household politics, manifest as rights and welfare politics.

People–class politics, which has particular implications under contemporary globalization as workers of different nationalities are pitted against each other and often within the same sovereign space.

People–household politics reflects the disputes around cultural issues, especially those that propose normative views of family structure.

Class–household politics, especially the struggles that emerge from the feminization of the workforce in what have been traditionally male preserves and the interrelationship between changes in the workplace and gender roles in the family.

The fourteen politics are only briefly outlined here, but they serve to illustrate an important point regarding the framing of questions through the traditional practices of social science disciplines. The existence of disciplines serves to compartmentalize these politics as separate struggles or issues. For example, political science lays claim to studying intrastate politics while the separate field of international relations studies interstate politics. Sociology would seem the discipline to provide knowledge about class politics, but this too would be split between those studying class and those studying gender (households) or race (“peoples”). Not only does the fourteen-politics framework expose the poverty of separating politics in this way, but it also exposes the limited number of politics that are usually analyzed. For example, there is much more research conducted on interstate politics than there is on, say, people–class politics.

The contribution of the fourteen-politics framework is its placement of politics largely ignored by social science on an equal footing with dominant topics. Research questions regarding, for example, people–household politics rather than inter-class politics allow the research subjects to be seen as more complex actors than in singular frameworks. In other words, a striking worker may be seen as more than just a member of the proletariat, but as a mother, of a certain generation, in a particular family setting, and of ethnic, racial, and national identity. Research open to the different crosscutting politics would be more likely to identify the identities and politics most important to the actors themselves, rather than those defined by a series of separate academic frameworks.

The benefits of the fourteen-politics framework are relevant to those studying, ostensibly, states. The use of geographic scale, discussed earlier, in conjunction with the fourteen politics requires a movement away from methodological nationalism and the accompanying assignment of the state as a singular actor and an expression of the state as the manifestation or effect of multiple political agents. The fourteen politics requires consideration of a multi-scalar political geography in which the competing goals and identities of actors are framed by their multiple struggles within, or as, the four institutions. Saying “within, or as” acknowledges the utility of conceptualizing institutions in some analyses as actors while seeing other institutions as disaggregated and contested. For example, studying NIMBY politics regarding the international disposal of nuclear waste could focus on the mobilization of households in neighborhood politics, in a manner that disaggregates the local state but not the households. Alternatively, the agenda chosen by neighborhood organizations may best be understood by disaggregating the household politics of gender and generation. The bottom line is that the fourteen geographies derived from the institutional politics facilitate a flexible research agenda that allows for concentration upon particular politics within particular institutions as best suits the question. The possibility is also provided to approach the same issue through a variety of institutional politics or, in other words, different lenses.

A key implication of the fourteen institutional politics is a counterintuitive interpretation of the role of the state in anti-systemic politics. To borrow Taylor’s ( 1991b ) phrase, the state is Quisling (the term Quisling has become synonymous with “traitor” in some cultures because of Vidkun Quisling’s role as Minister-President of Norway in World War II and his collaboration with the Nazis). Class politics and anti-imperialist politics have long operated under the assumption that their goals can be best achieved by seizing control of the state apparatus. The working classes have organized political parties with the aim of winning elections and controlling the government, or sought to achieve the same goal through revolution. The irony is that either strategy is likely to result in failure as controlling the state apparatus does not change the political structure of the capitalist world-economy. The same can be said for anti-colonial politics, which has sought to gain emancipation from domination through national self-determination. The global South is comprised of states that are nominally independent but still constrained by the core–periphery structure of the world-economy.

Seeing the state as Quisling requires reference back to Taylor’s three scales and the structure of the capitalist world-economy as a single economic unit comprised of multiple political entities, namely states. The scope of the social system is the capitalist world-economy, and it is at that scale that processes ultimately operate. Hence, political change should be targeted at this same scale. Taking control of the state apparatus, by reform or revolution, allows a political movement to attempt to use state borders to ameliorate a state’s position in the world-economy. However, the essential structure of the social system remains unchanged. The state is conceived of as Quisling because it betrays the goals of political movements. It provides the illusion of progressive change through seizing government control while the system-wide structures generating inequality and difference remain. A historic example is the transition of the Bolshevik revolution from an international agenda to change the historical social system to the Stalinist project of socialism in one state. In the language of Peter Taylor , the international socialist revolution was initially aimed at the scale of the social structure but its goals were betrayed by subsequent targeting of the control of the state apparatus rather than changing the historical social system.

Beginning in the 1990s, decentering the state has become more commonplace in social science, perhaps with the exception of quantitative IR studies. For example, Hardt and Negri’s ( 2000 ) definition of empire depicted a world society of many intersecting transnational institutions that bypass states and, apparently, offer venues for progressive politics. Hardt and Negri’s global view mirrors contemporary theoretical discussion of the state in which the state itself is seen as a disaggregated set of institutions rather than a coherent or monolithic singular institution (Mitchell 1991 ; Jessop 2001 ). In light of these theoretical developments, the identification of the state as an institution in and of itself in world-systems theory is in danger of becoming anachronistic. On the other hand, identifying the state as the scale of ideology was a very timely and insightful contribution.

The initial strengths of the world-systems view of the state were to identify it as one of many arenas of politics and to situate it within the broader structure of the capitalist world-economy. However, in the contemporary poststructuralist environment of social science the world-systems approach to the state comes across as functionalist and rigid. The state is assigned a role of facilitating capital accumulation, through its ability to fracture antisystemic movements and offer capitalists quasi-monopolies, and this limited role varies from state –to state only in terms of a three-way category of core, periphery, and semi-periphery. Contemporary social science focus upon difference and contingency does not see explanatory value in functional and structural views of the state.

Perhaps it is not surprising that most geographic work using world-systems theory did not focus upon the state. One exception is in the subfield of electoral geography, in which world-systems theory was used to situate or contextualize intrastate politics within the broader structures of the capitalist world-economy. The seminal work was by Taylor ( 1984 ; 1986 ), who discussed the evolution of the system of political parties that became established in Europe within the processes of the wider social system. The term “politics of failure” was used to explain the lack of politics in the periphery of the world-economy (Osei-Kwame and Taylor 1984 ). The flow of profit and resources from periphery to core in the capitalist world-economy leaves little ability for governments in the former to build upon campaign promises and legitimate their rule. Hence, polities in the periphery are usually nondemocratic and require either an authoritarian government to secure control or are blighted by frequent changes in government by coup. In those peripheral countries where elections do take place, the nature of the electorate is unstable as new promises must be made to new constituents at each election. For example, the longevity of Congress party control in India from 1952 through 1977 displayed such a fluid pattern as the party was abandoned by its voters in previous elections and constructed a new geography of support (Flint and Taylor 2007 :229–33). In another study Flint ( 2001a ) situated the electoral rise of the Nazi party through its ability to create a national agenda that appealed to a number of constituencies experiencing economic stresses that were traced back to the dynamics of the capitalist world-economy.

However, overall the functionalist approach to the state has limited political geographers’ adoption of world-systems theory. In general, most political geography has taken a step back from the grand and global schema that would make world-systems theory an appropriate choice. Instead, the focus is upon the micro-scale of “everyday experiences” and the prosaic influence of the state (Painter 2006 ). Politics is increasingly identified as contingent and best addressed at scales that illustrate individual interactions with political structures. In this intellectual climate it is perhaps not surprising that political geography has utilized the broad scope of world-systems theory to explore alternative frameworks or meta-geographies.

Revisualizing the World Political Map

The term meta-geography refers to an overarching geographical structure or pattern and the related normative understanding of how things “should be” spatially organized. With regard to political geography, the combination of the real and the perceived is centered upon the Westphalian system of states, that are perceived as the “obvious” and “correct” way to organize politics through the broad acceptance of the ideology of nationalism (Taylor 1994 ; 1995 ). In turn, this meta-geography has framed mainstream social science by promoting methodological nationalism, which itself has established an analytical framework that has reinforced the perception of states as sovereign containers of society. This dominant view of the way the world is organized has been eroded recently through the twin concepts of globalization and transnationalism.

It is not the purpose of this essay to fully explore the rich literature underlying these two concepts. Instead, the related concept of global city (Sassen 2006 ) has been used as a basis for a large analytical project that is organized by world-systems theory. The Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) laboratory at the University of Loughborough ( www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc ) has led the way in creating databases and conducting analyses that utilize a meta-geography of connectivity between cities rather than the territoriality of states. Much of this project has been devoted to collecting data on economic linkages between cities. This was an important step in creating a new meta-geographic framework as statistics are based upon the content of a geographical unit (census tracts or states) rather than the ties between entities, though the dyadic organization of IR databases such as the Correlates of War project are important exceptions. Beginning by counting the number of offices of globally operating service providers (financial services, advertising companies, specialized lawyers, etc.), the project classified cities into a global hierarchy. Subsequently, the connectivity between cities was calculated so that the meta-geography organizing the capitalist world-economy was one of nodes (the cities themselves) and linkages (the intra- and interfirm connections between offices).

The initial phases of the GaWC project were necessarily data driven (see a full list and chronology of publications at www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/publicat.html ). However, from this foundation has come a reinterpretation of political geography that blends the agency of firms, governments, and NGOs with the structure of the capitalist world-economy (Taylor 2005 ). By analyzing three sets of city networks (diplomatic offices, NGOs, and UN agencies) the pattern of global intercity interaction reveals the processes that simultaneously maintain the Westphalian system and the core–periphery hierarchy facilitating capital accumulation while also enabling transnational politics with antisystemic potential. The intersection of these three networks results in a certain amount of mutual constitution but also antagonism as they strive for alternative geographies (state sovereignty and transnationalism). The constraints and possibilities of such interactions are situated within the structures of the capitalist world-economy, but without eliminating their transformative potential. The activities of these different sets of actors are framed by different political geographic goals, but as an analytical focus the work of GaWC is encouraging scholars to frame their analyses within a meta-geography of networks rather than territorial states.

The empirical project centered upon GaWC can be interpreted as the political geography of world-systems theory further developing understanding of the core–periphery hierarchy of the capitalist world-economy, and another operationalization of the duality of agency and structure. Taylor’s three scales of political geography situated everyday experiences within the broad processes and structure of the capitalist world-economy. Subsequent analysis of electoral politics attempted to do the same thing. Theoretical explorations of the state and the politics of the institutions promoted, through the labeling of the state as the scale of ideology, a realization of the problems of identifying states as the key political actor. The result has been a return to an empirical project that frames the everyday actions of firms and organizations within particular cities as the agency that maintains and, to some degree, transforms the structures of the historical social system.

Whither World-Systems Analysis?

The future of world-systems theory as a useful framework for the geographic study of international relations rests on a paradox. If current theoretical developments in the social sciences continue the future appears bleak, but compelling real-world events and trends seem to fit expectations drawn from world-systems theory: for example, contemporary discussion of protectionist policies and questions of challenge to the US’s hegemonic position. The poststructural doctrines of contingency and fluidity run counter to the structural imperatives that are the foundation of world-systems theory. Furthermore, the formal hypothesis construction of quantitative IR is incompatible with such a historically deterministic framework (Popper 1957 ). An outgrowth of Marxist thought, world-systems theory appears irrelevant to, for example, theories of the state (Jessop 2001 ) or democracy (Laclau and Mouffe 2001 ) that are framed by the operation of capitalism but avoid a structuralist or deterministic framework.

Despite these challenges, the imprint of world-systems theory upon human geography has been profound. The work of political geographers such as John Agnew and Stuart Corbridge ( 1995 ) resonated with world-systems theory’s focus upon the global scale, as well as the idea of the US as hegemonic, or primary, state in a competitive system of states (Agnew 2005 ). David Harvey ’s critique of world-systems theory as functionalist was to some degree accurate, but his work on contemporary US policy is, at the least, in the spirit of world-systems theory, and arguably illuminates similar structures and practices (Harvey 2003 ). The political geography approach to world-systems theory has framed questions of economic development implicitly even as its explicit presence has waned.

However, perhaps “real-world” events may reinvigorate a world-systems theory approach to political geography. The contemporary social context of US-led war across the globe, consistent disparities of wealth across the globe, and economic downturn and competition were the staples of world-systems theory that underpinned its initial appeal in the 1970s and 1980s. The space–time matrix that was a key component of introducing world-systems theory to political geography offers an interpretation of contemporary economic restructuring. The contemporary economic, political, and military challenges to the US may also be interpreted through the paired-Kondratieff model of hegemony discussed earlier. More specifically, does a political–economic context in which the Economist ( 2009 ) can decry “The Return of Economic Nationalism” and news commentators spout comparisons of today with the Great Depression (Gross 2008 ) promote the need for a historical model such as world-systems theory with its emphasis upon cycles?

This essay suggests that the answer is “perhaps.” As a heuristic device the questions that can be posed by considering the dynamics of Kondratieff waves and hegemonic cycles and the structure of the core and periphery hierarchy are most useful. The goal should not be to focus upon the inevitability of events that the historicism of the framework promotes. For example, how long will the next B-phase, or depression, last, or does the financial crisis of 2009 suggest that the mechanism of Kondratieff waves, and its associated timing, has broken down altogether? Instead, the benefit can be to assume a tendency toward economic stagnation and restructuring after a period of growth and ask questions about contemporary politics based on “what if” scenarios. For example, if the next Kondratieff wave will be based on a new regional concentration of a new technology, which region and what technology? Or, do the R&D policies of, say, India, China, the European Union, and the United States suggest a greater competitive advantage for one of these actors compared to the others? With regard to hegemonic cycles, an assumed tendency to increased political challenge poses questions regarding the broader meaning of the global war on terror and whether it suggests US weakness or strength and continued leadership (Flint 2005 ).

However, it must be acknowledged that world-systems theory is a poor analytical framework to study social processes. The ability to generate testable hypotheses from world-systems theory is limited (Popper 1957 ), though Chase-Dunn’s ( 1989 ) attempt was valuable but did not produce a body of research. The emphasis of the theory upon macro-processes that are historically and functionally deterministic precludes research designs that are based upon the potential variation in the behavior of social actors. In fact, Popper’s critique is that the historicism of a theory such as world-systems either precludes an investigation of social choices or is so all-encompassing that any behavioral pattern can be explained one way or the other.

The strength of world-systems theory lies in its ability to portray a broad temporal and spatial scenario, one that situates apparently isolated events and actors within broader processes. This Braudelian goal of understanding the immediate and everyday actions and options of actors was the beginning point for world-systems theory (Braudel 1973 ; 1984 ). It also underlies Taylor’s goal of a political geography of different experiences and opportunities for individuals within different geographic settings. However, over the course of the development of world-systems theory the macro became more emphasized than the micro or meso. Perhaps this is inevitable as it is, primarily, a historical and structural framework. On the other hand, perhaps we are doing the actors we want to study a disservice by denying structural constraints. Of course, critics would say the exact opposite: that a structural model defines and determines actors unfairly, by letting the model dictate the meaning of their actions rather than acknowledging their reflexivity. And yet, in a world where gross disparities in wealth remain despite numerous theories and programs of “development,” a world in which the global South remains dominated by the institutions of the rich and powerful countries, a world in which one country has the power to project military power and set the global agenda, and a world in which challenges to that one country in terms of political extremism, terrorism, insurgency, counterterrorism, and counterinsurgency create such mayhem and misery it would be rash to diminish the role of core and periphery structures and hegemonic powers in shaping the opportunities and constraints faced by individuals, households, states, and “peoples.”

- Agnew, J.A. (1987) Place and Politics . London: Allen and Unwin.

- Agnew, J.A. (2005) Hegemony: The New Shape of Global Power . Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Agnew, J.A. , and Corbridge, S. (1995) Mastering Space: Hegemony, Territory and International Political Economy . New York: Routledge.

- Agnew, J.A. , Mitchell, K. , and Toal, G. (2007) A Companion to Political Geography . Oxford: Blackwell.

- Arrighi, G. (1994) The Long Twentieth Century . London: Verso.

- Berry, B.J.L. (1969) Book Review. Geographical Review 59, 450–51.

- Braudel, F. (1973) Capitalism and Material Life 1400–1800 . London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

- Braudel, F. (1984) The Perspective on the World . London: Collins.

- Chase-Dunn, C.K. (1989) Global Formation . Oxford: Blackwell.

- Cox, K.R. (1973) Conflict, Power and Politics in the City: A Geographic View . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Cox, K.R. , Low, M. , and Robinson, J. (2008a) Introduction: Political Geography: Traditions and Turns. In K.R. Cox , M. Low , and J. Robinson (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Political Geography . Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 1–14.

- Cox, K.R. , Low, M. , and Robinson, J. (eds.) (2008b) The Sage Handbook of Political Geography . Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dezzani, R.J. (2001) Classification Analysis of World Economic Regions. Geographical Analysis 33, 330–52.

- Dodds, K.J. , and Atkinson, D. (2000) Geopolitical Traditions: A Century of Geopolitical Thought . New York: Routledge.

- The Economist (2009) The Return of Economic Nationalism (Feb. 7–13), 9–10.

- Flint, C. (1999) Changing Times, Changing Scales: World Politics and Political Geography since 1890. In G. Demko , and W.B. Wood (eds.) Reordering the World , 2nd edn. Boulder: Westview, pp. 19–39.

- Flint, C. (2001a) A TimeSpace for Electoral Geography: Economic Restructuring, Political Agency and the Rise of the Nazi Party. Political Geography 20, 301–29.

- Flint, C. (2001b) Right-Wing Resistance to the Process of American Hegemony: The Changing Political Geography of Nativism in Pennsylvania, 1920–1998. Political Geography 20, 763–83.

- Flint, C. (2001c) The Geopolitics of Laughter and Forgetting: A World-Systems Interpretation of the Post Modern Geopolitical Condition. Geopolitics 6, 1–16.

- Flint, C. (2005) Dynamic Metageographies of Terrorism: The Spatial Challenges of Religious Terrorism and the “War on Terrorism.” In C. Flint (ed.) The Geography of War and Peace . Oxford; Oxford University Press, pp. 198–216.

- Flint, C. , and Taylor, P.J. (2007) Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State and Locality , 5th edn. Harlow: Pearson.

- Gross, D. (2008) Don’t Get Depressed, It’s Not 1929: Why All Those Great Depression Analogies are Wrong. Slate Nov. 22. At www.slate.com/id/2205186 , accessed Apr. 9, 2009.

- Hardt, M. , and Negri, A. (2000) Empire . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hartshorne, R. (1950) The Functional Approach in Political Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 40, 95–130.

- Harvey, D. (1973) Social Justice and the City . London: Arnold.

- Harvey, D. (1985) The Geopolitics of Capitalism. In D. Gregory , and J. Urry (eds.) Social Relations and Spatial Structures . London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 128–63.

- Harvey, D. (2003) The New Imperialism . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jessop, B. (2001) Bringing the State Back In (Yet Again): Reviews, Revisions, Rejections, and Redirections. International Review of Sociology 11, 149–73.

- Johnston, R.J. (2001) Out of the “Moribund Backwater”: Territory and Territoriality in Political Geography. Political Geography 20, 677–93.

- Johnston, R.J. , and Sidaway, J.D. (2004) Geography and Geographers: Anglo-American Human Geography Since 1945 , 6th edn. London: Hodder.

- Johnston, R.J. , O’Loughlin, J. , and Taylor, P.J. (1987) The Geography of Violence and Premature Death: A World-Systems Approach. In R. Varynen , D. Senghaas , and C. Schmidt (eds.) The Quest for Peace . London: Sage, pp. 241–59.

- Kuus, M. (2009) Political Geography and Geopolitics. Canadian Geographer 53, 86–90.

- Kuus, M. , and Agnew, J. (2008) Theorizing the State Geographically: Sovereignty, Subjectivity, Territoriality. In K.R. Cox , M. Low , and J. Robinson (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Political Geography . Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 95–106.

- Laclau, E. , and Mouffe, C. (2001) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics . London: Verso.

- Marston, S.A. (2000) The Social Construction of Scale. Progress in Human Geography 24, 219–42.

- Mitchell, T. (1991) The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and Their Critics. American Political Science Review 85, 77–96.

- Osei-Kwame, P. , and Taylor, P.J. (1984) A Politics of Failure: The Political Geography of Ghanaian Elections, 1954–1979. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 74, 574–89.

- Ó Tuathail, G. (1996) Critical Geopolitics . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Painter, J. (2006) Prosaic Geographies of Stateness. Political Geography 25, 752–74.

- Peet, R. (1998) Modern Geographical Thought . Oxford: Blackwell.

- Popper, K. (1957) The Poverty of Historicism . Boston: Beacon.

- Sassen, S. (2006) Cities in a World Economy , 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge.

- Sayer, R. (1992) Method in Social Science: A Realist Approach . London: Routledge.

- Shelley, F.M. , and Flint, C. (2000) Geography, Place and World-System Analysis. In T.D. Hall (ed.) A World-Systems Reader: New Perspectives on Gender, Urbanism, Cultures, Indigenous Peoples, and Ecology . Boulder: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 69–82.

- Skocpol, T. (1977) Wallerstein’s World-Capitalist System: A Theoretical and Historical Critique. American Journal of Sociology 82, 1075–90.

- Taylor, P.J. (1981a) Political Geography and the World-Economy. In A.D. Burnett , and P.J. Taylor (eds.) Political Studies from Spatial Perspectives . New York: John Wiley, pp. 157–72.

- Taylor, P.J. (1981b) Geographical Scales within the World-Economy Approach. Review 5, 3–11.

- Taylor, P.J. (1982) A Materialist Framework for Political Geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers NS7, 15–34.

- Taylor, P.J. (1984) Accumulation, Legitimation and the Electoral Geographies within Liberal Democracies. In P.J. Taylor , and J.W. House (eds.) Political Geography: Recent Advances and Future Directions . London: Croom Helm, pp. 117–32.

- Taylor, P.J. (1985) Political Geography: World-Economy, Nation-State, and Locality . Harlow: Longman.

- Taylor, P.J. (1986) An Exploration into World-Systems Analysis of Political Parties. Political Geography Quarterly 5 (suppl.), 5–20.

- Taylor, P.J. (1987) The Paradox of Geographical Scale in Marx’s Politics. Antipode 19, 287–306.

- Taylor, P.J. (1990) Britain and the Cold War: 1945 as Geopolitical Transition . London: Pinter.

- Taylor, P.J. (1991a) The Changing Political Geography. In R.J. Johnston , and V. Gardiner (eds.) The Changing Geography of the United Kingdom , 2nd edn. London: Routledge, pp. 316–42.

- Taylor, P.J. (1991b) The Crisis of the Movements: The Enabling State as Quisling. Antipode 23, 214–28.

- Taylor, P.J. (1991c) Political Geography within World-Systems Analysis. Review 14, 387–402.

- Taylor, P.J. (1992) Nationalism, Internationalism and a “Socialist Geopolitics.” Antipode 25, 327–36.

- Taylor, P.J. (1993) The Last of the Hegemons: British impasse, American Impasse, World Impasse. Southeastern Geographer XXXIII, 1–22.

- Taylor, P.J. (1994) The State as Container: Territoriality in the Modern World-System. Progress in Human Geography 18, 151–62.

- Taylor, P.J. (1995) Beyond Containers: Internationality, Interstateness, Interterritoriality. Progress in Human Geography 19, 1–15.

- Taylor, P.J. (1996) The Way the Modern World Works: World Hegemony to World Impasse . Chichester: John Wiley.

- Taylor, P.J. (1998) Modernities: A Geohistorical Interpretation . Cambridge: Polity.

- Taylor, P.J. (2005) New Political Geographies: Global Civil Society and Global Governance through World City Networks. Political Geography 24, 703–30.

- Terlouw, C.P. (1992) The Regional Geography of the World-System . Utrecht: Rijksuniversiteit.

- van der Wusten, H. (2005) Violence, Development, and Political Order. In C. Flint (ed.) The Geography of War and Peace . Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 61–84.

- Wallerstein, I. (1979) The Capitalist World-Economy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (1984) The Politics of the World-Economy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (1991) Unthinking Social Science . Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (2003) The Decline of American Power . New York: New Press.

- Wallerstein, I. (2004) World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction . Durham: Duke University Press.

Links to Digital Materials

Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations. At www.binghamton.edu/fbc , accessed Apr. 14, 2009. The Fernand Braudel Center is the intellectual home of the world-systems theory project. The website offers newsletters, conference reviews, and discussions of ongoing research.

Journal of World-Systems Research. At www.jwsr.ucr.edu/index.php , accessed Apr. 14, 2009. The Journal of World-Systems Research highlights the diversity and vibrancy of world-systems theory research.

Globalization and World Cities Research Network. At www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc , accessed Apr. 14, 2009. For a specific insight into geographic research using a world-systems approach, the GaWK research network site gives access to papers and databases. Though based at Loughborough University in the UK, it provides links to world city research projects across the world.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to Ron Johnston and Herman van der Wusten for their helpful comments and insights. I also thank Peter Taylor for his contributions to human geography and my own career in particular.

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, International Studies. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 16 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Character limit 500 /500

Globalization from a World-System Perspective: A New Phase in the Core?A New Destiny for Brazil and the Semiperiphery

- Kathleen C. Schwartzman University of Arizona

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- The Author retains copyright in the Work, where the term “Work” shall include all digital objects that may result in subsequent electronic publication or distribution.

- Upon acceptance of the Work, the author shall grant to the Publisher the right of first publication of the Work.

- Attribution—other users must attribute the Work in the manner specified by the author as indicated on the journal Web site;

- The Author is able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the nonexclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the Work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), as long as there is provided in the document an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post online a prepublication manuscript (but not the Publisher’s final formatted PDF version of the Work) in institutional repositories or on their Websites prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work. Any such posting made before acceptance and publication of the Work shall be updated upon publication to include a reference to the Publisher-assigned DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and a link to the online abstract for the final published Work in the Journal.

- Upon Publisher’s request, the Author agrees to furnish promptly to Publisher, at the Author’s own expense, written evidence of the permissions, licenses, and consents for use of third-party material included within the Work, except as determined by Publisher to be covered by the principles of Fair Use.

- the Work is the Author’s original work;

- the Author has not transferred, and will not transfer, exclusive rights in the Work to any third party;

- the Work is not pending review or under consideration by another publisher;

- the Work has not previously been published;

- the Work contains no misrepresentation or infringement of the Work or property of other authors or third parties; and

- the Work contains no libel, invasion of privacy, or other unlawful matter.

- The Author agrees to indemnify and hold Publisher harmless from Author’s breach of the representations and warranties contained in Paragraph 6 above, as well as any claim or proceeding relating to Publisher’s use and publication of any content contained in the Work, including third-party content.

Revised 7/16/2018. Revision Description: Removed outdated link.

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Kathleen C. Schwartzman, Will China's Development lead to Mexico's Underdevelopment? , Journal of World-Systems Research: Volume 21, Number 1, Winter/Spring 2015

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section World-System Theory

Introduction.

- Dependency Theory

- Emergence of the World-Systems Perspective

- Elaborators I

- Elaborators II

- Global Commodity and Value Chains

- International Relations Theory and the World-System Perspective

- Women and Gender

- Racism, Ethnogenesis, and Slavery

- Hegemonic Rise and Fall and Global Social Movements

- Ecology, Environment, and Climate Change

- Regional Applications: Africa, Latin America, Asia

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Academic Theories of International Relations Since 1945

- International Relations Theory

- Social Scientific Theories of Imperialism

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Crisis Bargaining

- History of Brazilian Foreign Policy (1808 to 1945)

- Indian Foreign Policy

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

World-System Theory by Christopher Chase-Dunn , Marilyn Grell-Brisk LAST REVIEWED: 26 November 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 26 November 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0272

The world-system perspective emerged during the world revolution of 1968 when social scientists contemplated the meaning of Latin American dependency theory for Africa. Immanuel Wallerstein, Terence Hopkins, Samir Amin, Andre Gunder Frank, and Giovanni Arrighi developed slightly different versions of the world-system perspective in interaction with each other. The big idea was that the global system had a stratified structure on inequality based on institutionalized exploitation. This implied that the whole system was the proper unit of analysis, not national societies, and that development and underdevelopment had been structured by global power relations for centuries. The modern world-system is a self-contained entity based on a geographically differentiated division of labor and bound together by a world market. In Wallerstein’s version capitalism had become predominant in Europe and its peripheries in the long 16th century and had expanded and deepened in waves. The core states were able to concentrate the most profitable economic activities and they exploited the semi-peripheral and peripheral regions by means of colonialism and the emergent international division of labor, which relies on unequal exchange . The world-system analysts all focused on global inequalities, but their terminologies were somewhat different. Amin and Frank talked about center and periphery. Wallerstein proposed a three-tiered structure with an intermediate semiperiphery between the core and the periphery, and he used the term core to suggest a multicentric region containing a group of states rather than the term center , which implies a hierarchy with a single peak. When the world-system perspective emerged, the focus on the non-core (periphery and semiperiphery) was called Third Worldism. Current terminology refers to the Global North (the core) and the Global South (periphery and semiperiphery).