- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 2, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

The RMS Titanic, a luxury steamship, sank in the early hours of April 15, 1912, off the coast of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic after sideswiping an iceberg during its maiden voyage. Of the 2,240 passengers and crew on board, more than 1,500 lost their lives in the disaster. Titanic has inspired countless books, articles and films (including the 1997 Titanic movie starring Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio), and the ship's story has entered the public consciousness as a cautionary tale about the perils of human hubris.

The Building of the RMS Titanic

The Titanic was the product of intense competition among rival shipping lines in the first half of the 20th century. In particular, the White Star Line found itself in a battle for steamship primacy with Cunard, a venerable British firm with two standout ships that ranked among the most sophisticated and luxurious of their time.

Cunard’s Mauretania began service in 1907 and quickly set a speed record for the fastest average speed during a transatlantic crossing (23.69 knots or 27.26 mph), a title that it held for 22 years.

Cunard’s other masterpiece, Lusitania , launched the same year and was lauded for its spectacular interiors. Lusitania met its tragic end on May 7, 1915, when a torpedo fired by a German U-boat sunk the ship, killing nearly 1,200 of the 1,959 people on board and precipitating the United States’ entry into World War I .

Did you know? Passengers traveling first class on Titanic were roughly 44 percent more likely to survive than other passengers.

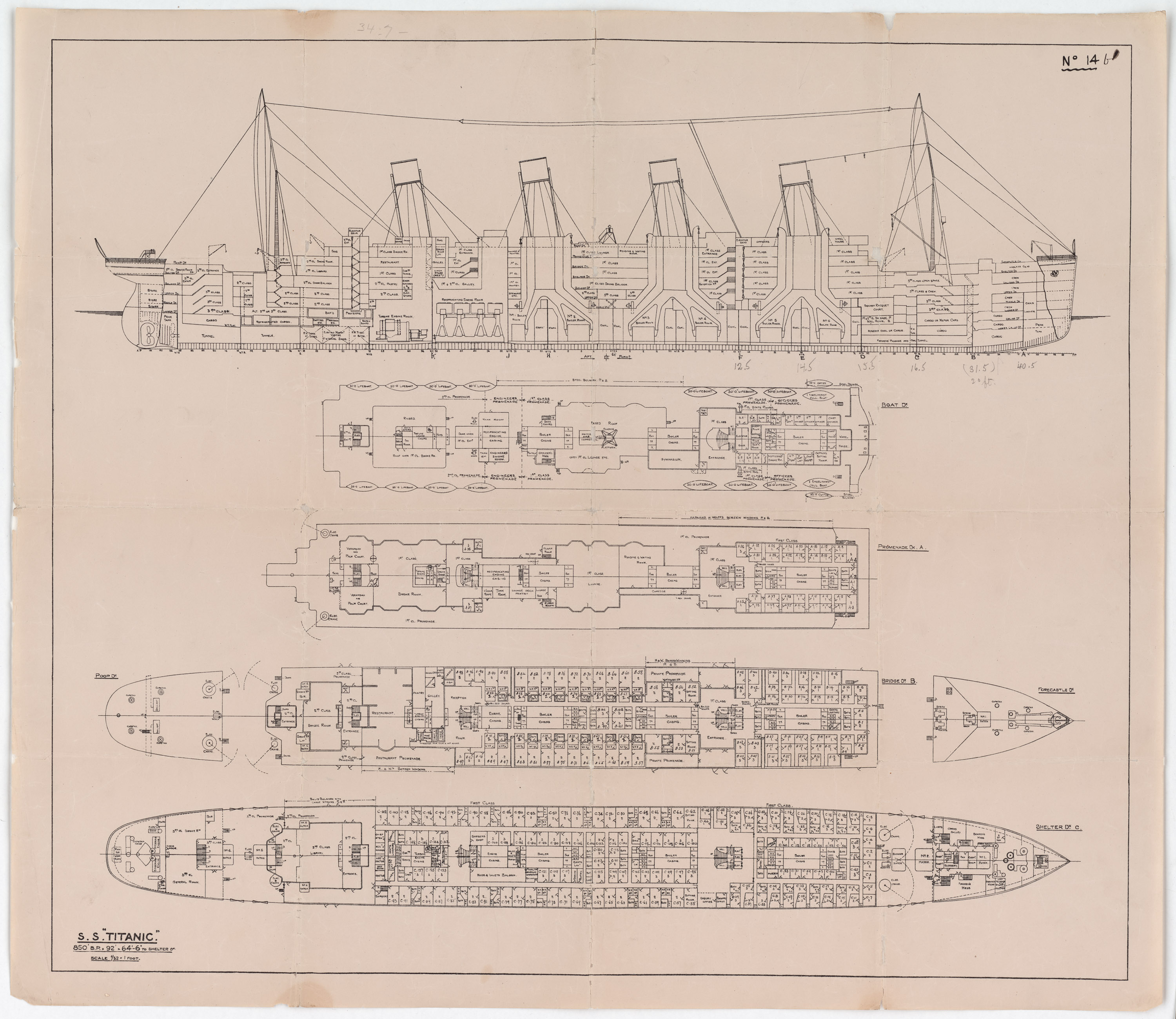

The same year that Cunard unveiled its two magnificent liners, J. Bruce Ismay, chief executive of White Star, discussed the construction of three large ships with William J. Pirrie, chairman of the shipbuilding company Harland and Wolff. Part of a new “Olympic” class of liners, each ship would measure 882 feet in length and 92.5 feet at their broadest point, making them the largest of their time.

In March 1909, work began in the massive Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland, on the second of these three ocean liners, Titanic, and continued nonstop for two years.

On May 31, 1911, Titanic’s immense hull–the largest movable manmade object in the world at the time–made its way down the slipways and into the River Lagan in Belfast. More than 100,000 people attended the launching, which took just over a minute and went off without a hitch.

The hull was immediately towed to a mammoth fitting-out dock where thousands of workers would spend most of the next year building the ship’s decks, constructing her lavish interiors and installing the 29 giant boilers that would power her two main steam engines.

‘Unsinkable’ Titanic’s Fatal Flaws

According to some hypotheses, Titanic was doomed from the start by a design that many lauded as state-of-the-art. The Olympic-class ships featured a double bottom and 15 watertight bulkhead compartments equipped with electric watertight doors that could be operated individually or simultaneously by a switch on the bridge.

It was these watertight bulkheads that inspired Shipbuilder magazine, in a special issue devoted to the Olympic liners, to deem them “practically unsinkable.”

But the watertight compartment design contained a flaw that was a critical factor in Titanic’s sinking: While the individual bulkheads were indeed watertight, the walls separating the bulkheads extended only a few feet above the water line, so water could pour from one compartment into another, especially if the ship began to list or pitch forward.

The second critical safety lapse that contributed to the loss of so many lives was the inadequate number of lifeboats carried on Titanic. A mere 16 boats, plus four Engelhardt “collapsibles,” could accommodate just 1,178 people. Titanic could carry up to 2,435 passengers, and a crew of approximately 900 brought her capacity to more than 3,300 people.

As a result, even if the lifeboats were loaded to full capacity during an emergency evacuation, there were available seats for only one-third of those on board. While unthinkably inadequate by today’s standards, Titanic’s supply of lifeboats actually exceeded the British Board of Trade’s requirements.

Passengers on the Titanic

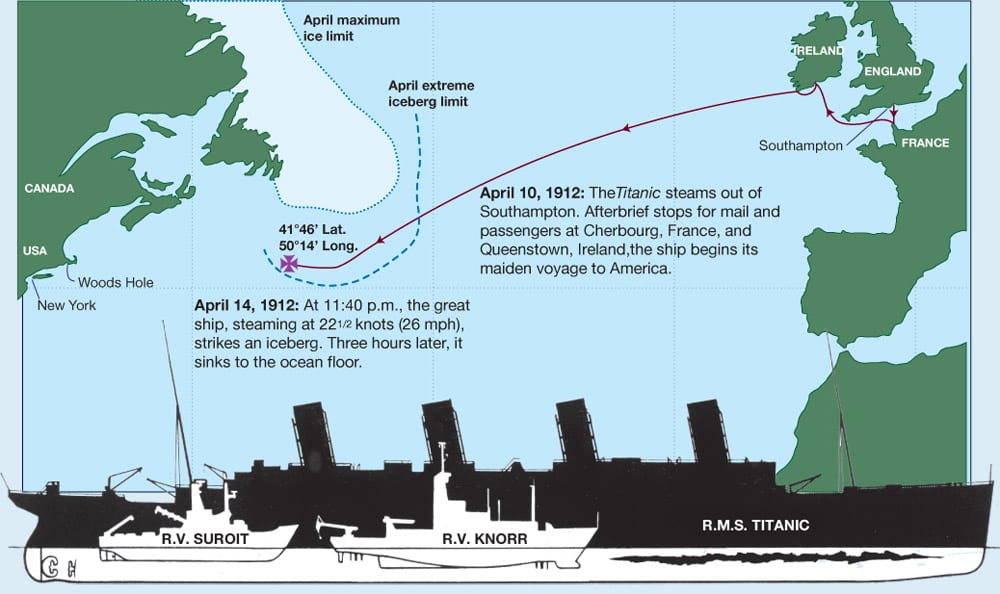

Titanic created quite a stir when it departed for its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, on April 10, 1912. After stops in Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown (now known as Cobh), Ireland, the ship set sail for New York with 2,240 passengers and crew—or “souls,” the expression then used in the shipping industry, usually in connection with a sinking—on board.

As befitting the first transatlantic crossing of the world’s most celebrated ship, many of these souls were high-ranking officials, wealthy industrialists, dignitaries and celebrities. First and foremost was the White Star Line’s managing director, J. Bruce Ismay, accompanied by Thomas Andrews, the ship’s builder from Harland and Wolff.

Absent was financier J.P. Morgan , whose International Mercantile Marine shipping trust controlled the White Star Line and who had selected Ismay as a company officer. Morgan had planned to join his associates on Titanic but canceled at the last minute when some business matters delayed him.

The wealthiest passenger was John Jacob Astor IV, heir to the Astor family fortune, who had made waves a year earlier by marrying 18-year-old Madeleine Talmadge Force, a young woman 29 years his junior, shortly after divorcing his first wife.

Other notable passengers included the elderly owner of Macy’s, Isidor Straus, and his wife Ida; industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim, accompanied by his mistress, valet and chauffeur; and widow and heiress Margaret “Molly” Brown, who would earn her nickname “ The Unsinkable Molly Brown ” by helping to maintain calm and order while the lifeboats were being loaded and boosting the spirits of her fellow survivors.

The employees attending to this collection of First Class luminaries were mostly traveling Second Class, along with academics, tourists, journalists and others who would enjoy a level of service and accommodations equivalent to First Class on most other ships.

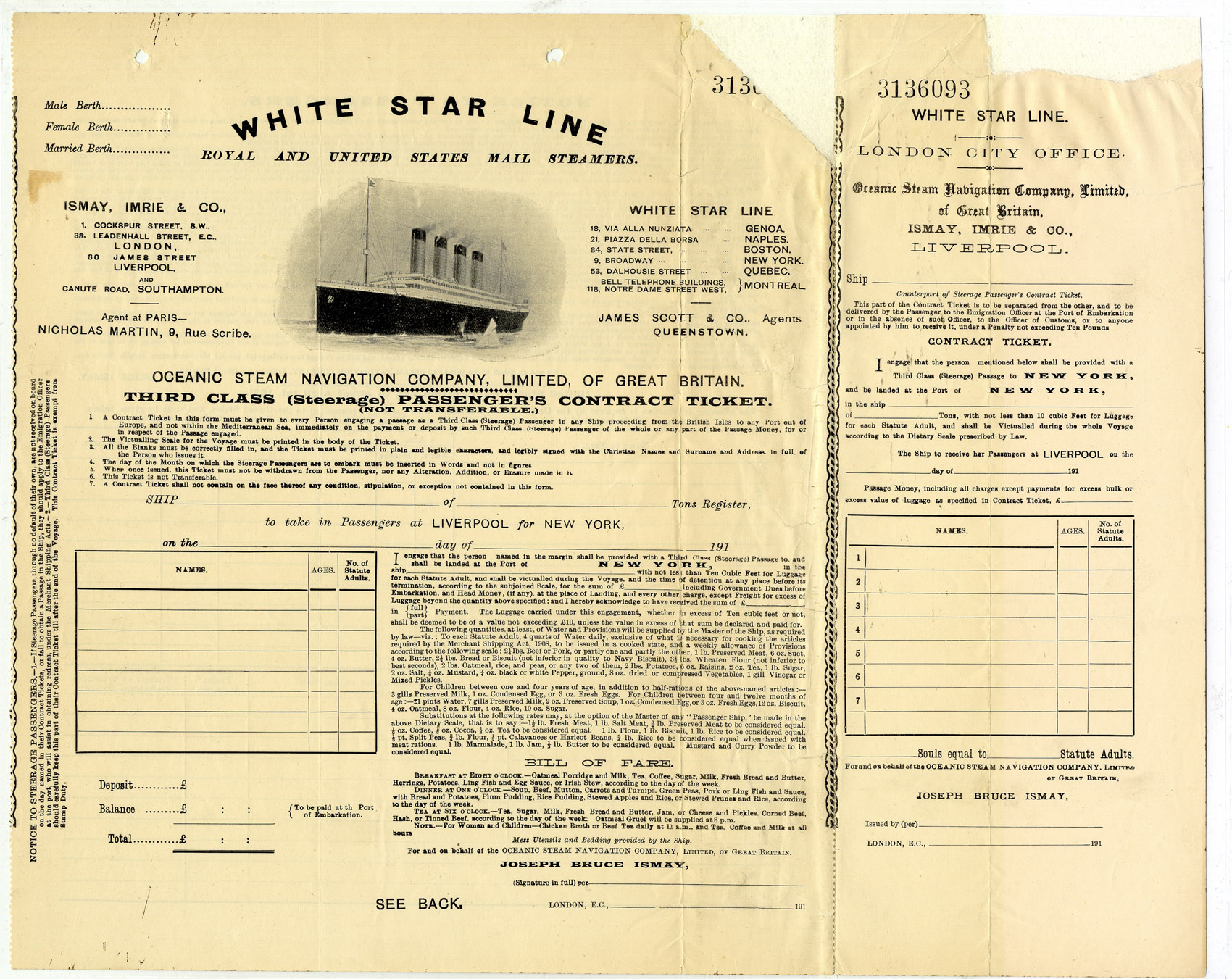

But by far the largest group of passengers was in Third Class: more than 700, exceeding the other two levels combined. Some had paid less than $20 to make the crossing. It was Third Class that was the major source of profit for shipping lines like White Star, and Titanic was designed to offer these passengers accommodations and amenities superior to those found in Third Class on any other ship of that era.

Titanic Sets Sail

Titanic’s departure from Southampton on April 10 was not without some oddities. A small coal fire was discovered in one of her bunkers–an alarming but not uncommon occurrence on steamships of the day. Stokers hosed down the smoldering coal and shoveled it aside to reach the base of the blaze.

After assessing the situation, the captain and chief engineer concluded that it was unlikely it had caused any damage that could affect the hull structure, and the stokers were ordered to continue controlling the fire at sea.

According to a theory put forth by a small number of Titanic experts, the fire became uncontrollable after the ship left Southampton, forcing the crew to attempt a full-speed crossing; moving at such a fast pace, they were unable to avoid the fatal collision with the iceberg.

Another unsettling event took place when Titanic left the Southampton dock. As she got underway, she narrowly escaped a collision with the America Line’s S.S. New York. Superstitious Titanic buffs sometimes point to this as the worst kind of omen for a ship departing on her maiden voyage.

The Titanic Strikes an Iceberg

On April 14, after four days of uneventful sailing, Titanic received sporadic reports of ice from other ships, but she was sailing on calm seas under a moonless, clear sky.

At about 11:30 p.m., a lookout saw an iceberg coming out of a slight haze dead ahead, then rang the warning bell and telephoned the bridge. The engines were quickly reversed and the ship was turned sharply—instead of making direct impact, Titanic seemed to graze along the side of the berg, sprinkling ice fragments on the forward deck.

Sensing no collision, the lookouts were relieved. They had no idea that the iceberg had a jagged underwater spur, which slashed a 300-foot gash in the hull below the ship’s waterline.

By the time the captain toured the damaged area with Harland and Wolff’s Thomas Andrews, five compartments were already filling with seawater, and the bow of the doomed ship was alarmingly pitched downward, allowing seawater to pour from one bulkhead into the neighboring compartment.

Andrews did a quick calculation and estimated that Titanic might remain afloat for an hour and a half, perhaps slightly more. At that point the captain, who had already instructed his wireless operator to call for help, ordered the lifeboats to be loaded.

Titanic’s Lifeboats

A little more than an hour after contact with the iceberg, a largely disorganized and haphazard evacuation began with the lowering of the first lifeboat. The craft was designed to hold 65 people; it left with only 28 aboard.

Tragically, this was to be the norm: During the confusion and chaos during the precious hours before Titanic plunged into the sea, nearly every lifeboat would be launched woefully under-filled, some with only a handful of passengers.

In compliance with the law of the sea, women and children boarded the boats first; only when there were no women or children nearby were men permitted to board. Yet many of the victims were in fact women and children, the result of disorderly procedures that failed to get them to the boats in the first place.

Exceeding Andrews’ prediction, Titanic stubbornly stayed afloat for close to three hours. Those hours witnessed acts of craven cowardice and extraordinary bravery.

Hundreds of human dramas unfolded between the order to load the lifeboats and the ship’s final plunge: Men saw off wives and children, families were separated in the confusion and selfless individuals gave up their spots to remain with loved ones or allow a more vulnerable passenger to escape. In the end, 706 people survived the sinking of the Titanic.

Titanic Sinks

The ship’s most illustrious passengers each responded to the circumstances with conduct that has become an integral part of the Titanic legend. Ismay, the White Star managing director, helped load some of the boats and later stepped onto a collapsible as it was being lowered. Although no women or children were in the vicinity when he abandoned ship, he would never live down the ignominy of surviving the disaster while so many others perished.

Thomas Andrews, Titanic’s chief designer, was last seen in the First Class smoking room, staring blankly at a painting of a ship on the wall. Astor deposited his wife Madeleine into a lifeboat and, remarking that she was pregnant, asked if he could accompany her; refused entry, he managed to kiss her goodbye just before the boat was lowered away.

Although offered a seat on account of his age, Isidor Straus refused any special consideration, and his wife Ida would not leave her husband behind. The couple retired to their cabin and perished together.

Benjamin Guggenheim and his valet returned to their rooms and changed into formal evening dress; emerging onto the deck, he famously declared, “We are dressed in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen.”

Molly Brown helped load the boats and finally was forced into one of the last to leave. She implored its crewmen to turn back for survivors, but they refused, fearing they would be swamped by desperate people trying to escape the icy seas.

Titanic, nearly perpendicular and with many of her lights still aglow, finally dove beneath the ocean’s surface at about 2:20 a.m. on April 15, 1912. Throughout the morning, Cunard’s Carpathia , after receiving Titanic’s distress call at midnight and steaming at full speed while dodging ice floes all night, rounded up all of the lifeboats. They contained only 706 survivors.

Aftermath of the Titanic Catastrophe

At least five separate boards of inquiry on both sides of the Atlantic conducted comprehensive hearings on Titanic’s sinking, interviewing dozens of witnesses and consulting with many maritime experts. Every conceivable subject was investigated, from the conduct of the officers and crew to the construction of the ship. Titanic conspiracy theories abounded.

While it has always been assumed that the ship sank as a result of the gash that caused the bulkhead compartments to flood, various other theories have emerged over the decades, including that the ship’s steel plates were too brittle for the near-freezing Atlantic waters, that the impact caused rivets to pop and that the expansion joints failed, among others.

Technological aspects of the catastrophe aside, Titanic’s demise has taken on a deeper, almost mythic, meaning in popular culture. Many view the tragedy as a morality play about the dangers of human hubris: Titanic’s creators believed they had built an unsinkable ship that could not be defeated by the laws of nature.

This same overconfidence explains the electrifying impact Titanic’s sinking had on the public when she was lost. There was widespread disbelief that the ship could not possibly have sunk, and, due to the era’s slow and unreliable means of communication, misinformation abounded. Newspapers initially reported that the ship had collided with an iceberg but remained afloat and was being towed to port with everyone on board.

It took many hours for accurate accounts to become widely available, and even then people had trouble accepting that this paragon of modern technology could sink on her maiden voyage, taking more than 1,500 souls with her.

The ship historian John Maxtone-Graham has compared Titanic’s story to the Challenger space shuttle disaster of 1986. In that case, the world reeled at the notion that one of the most sophisticated inventions ever created could explode into oblivion along with its crew. Both tragedies triggered a sudden collapse in confidence, revealing that we remain subject to human frailties and error, despite our hubris and a belief in technological infallibility.

Titanic Wreck

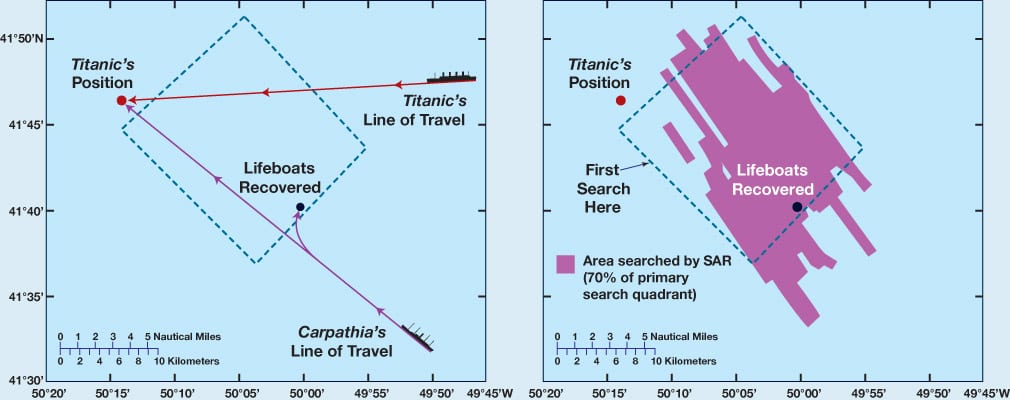

Efforts to locate the wreck of Titanic began soon after it sank. But technical limitations—as well as the vastness of the North Atlantic search area—made finding it extremely difficult.

Finally, in 1985, a joint U.S.-French expedition located the wreck of the RMS Titanic . The doomed ship was discovered about 400 miles east of Newfoundland in the North Atlantic, some 13,000 feet below the surface.

Subsequent explorations have found that the wreck is in relatively good condition, with many objects on the ship—jewelry, furniture, shoes, machinery and other items—are still intact.

Since its discovery, the wreck has been explored numerous times by manned and unmanned submersibles—including the submersible Titan, which imploded during what would have been its third dive to the wreck in June 2023.

HISTORY Vault: Titanic's Achilles Heel

Did Titanic have a fatal design flaw? John Chatterton and Richie Kohler of "Deep Sea Detectives" dive the wreckage of Titanic's sister ship, Britannic, to investigate the possibility.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

How the Titanic was lost and found

Researchers have pieced together debris from the Titanic to understand the final hours of the famed the ship and its passengers.

Many historical accounts of the sinking of the RMS Titanic describe the 882.5-foot-long passenger ship as “slipping beneath the ocean waves,” as though the vessel and its passengers drifted tranquilly off to sleep, but nothing could be further from the truth. Based on years of careful analysis of the wreck, which employed then state-of-the-art flooding models and simulations used in the modern shipping industry, experts are able to paint a gruesome portrait of Titanic ’s last hours and minutes.

Earlier this month, research on the ship continued as a team of experts completed five manned submersible dives at the site over an eight day span. Using high tech equipment, the team captured footage and images of the wreck that can be used to create 3D models for future augmented and virtual reality. The assets will help researchers further study the past and future of the ship.

The Titanic is in severe decay caused by salt corrosion and metal eating bacteria, Caladan Oceanic, the company overseeing the expedition, said in an announcement about the dives. A manned submersible reached the bottom of the north Atlantic Ocean in August.

The Titanic dive is being filmed by Atlantic Productions for the documentary special, "Mission Titanic", which will air globally on National Geographic in 2020.

“The most shocking area of deterioration was the starboard side of the officers’ quarters, where the captain’s quarters were,” said Titanic historian Parks Stephenson. The hull had started to collapse taking staterooms with it.

Scientists expect the erosion of the Titanic to continue.

“The future of the wreck is going to continue to deteriorate over time, it’s a natural process,” said scientist Lori Johnson.

The Titanic 's fate was sealed on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England to New York City. At 11:40 p.m. on April 14, 1912, the Titanic sideswiped an iceberg in the north Atlantic, buckling portions of the starboard hull along a 300-foot span and exposing the six forward watertight compartments to the ocean’s waters. From this moment onward, sinking was a certainty. The demise may have been hastened, however, when crewmen pushed open a gangway door on the port side of Titanic in an aborted attempt to load lifeboats from a lower level. Since the ship had begun listing to port, gravity prevented the crew from closing the massive door, and by 1:50 a.m., the bow had settled enough to allow seawater to rush in through the gangway.

By 2:18 a.m., with the last lifeboat having departed 13 minutes earlier, the bow had filled with water and the stern had risen high enough into the air to expose the propellers and create catastrophic stresses on the middle of the ship. Then the Titanic cracked in half.

You May Also Like

6 urgent questions on the missing Titanic submersible

You know how it sank. How was the Titanic dreamed up?

Inside the Titanic wreck's lucrative tourism industry

Once released from the stern section, the bow fell to the ocean floor at a fairly steep angle, nosing into the mud with such massive force that its ejecta patterns are still visible on the seafloor today.

The stern, lacking a hydrodynamic leading edge like the bow, tumbled and corkscrewed for more than two miles down to the ocean floor. Compartments exploded. Decks pancaked. Heavier pieces such as the boilers dropped straight down, while other pieces were flung off into the abyss.

The wreckage

For decades, a number of expeditions sought to find the Titanic without success—a problem compounded by the North Atlantic’s unpredictable weather, the enormous depth at which the sunken ship lies, and conflicting accounts of its final moments. Finally, 73 years after it sank, the final resting place of Titanic was located by National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Robert Ballard, along with French scientist Jean-Louis Michel, on September 1, 1985. The Titanic had come to rest roughly 380 miles (612 kilometers) southeast of Newfoundland in international waters. ( Discover how the Titanic was found during a secret Cold War mission. )

In the years since Ballard’s expedition, visitors to the site have made their mark: Modern trash litters the area, and some experts claim that submersibles have damaged the ship by landing on it or bumping into it. Organic processes are also relentlessly breaking down the Titanic : Mollusks have gobbled up most of the ship's wood while microbes eat away at exposed metal, forming icicle-like "rusticles."

"Everyone has their own opinion" as to how long Titanic will remain more or less intact , said research specialist Bill Lange of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

"Some people think the bow will collapse in a year or two," Lange said. "But others say it's going to be there for hundreds of years."

What was lost

More than 2,000 passengers and crew were aboard the Titanic ’s maiden voyage, but only 706 survived the trip.

Although the ocean liner could carry 3,511 passengers, the Titanic only had lifeboats for 1,178 people. To make matters worse, not all of the lifeboats were filled to capacity during the desperate evacuation of the doomed ship. Most of the Titanic ’s 1,500-odd victims died of hypothermia at the surface of the icy water. Hundreds of people may also have died inside the ship as it sank, most of them immigrant families in steerage class, looking forward to a new life in America.

Along with the lives lost, something else went down with the Titanic: An illusion of orderliness, a faith in technological progress, a yearning for the future that, as Europe drifted toward full-scale war, was soon replaced by fears and dreads all too familiar to our modern world. ( Test your knowledge of the famous ship. )

“The Titanic disaster was the bursting of a bubble,” said filmmaker James Cameron. “There was such a sense of bounty in the first decade of the 20th century. Elevators! Automobiles! Airplanes! Wireless radio! Everything seemed so wondrous, on an endless upward spiral. Then it all came crashing down.”

Related Topics

- UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY

- UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY

She survived the Titanic—but it wasn’t the only time she faced death at sea

This mysterious graveyard of shipwrecks was found far from sea

Clothing from 1600s shipwreck shows how the 1 percent lived

Exclusive: Wreck of fabled WWI German U-boat found off Virginia

How the 'wickedest city on Earth' was sunk by an earthquake

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Prologue Magazine

They Said It Couldn’t Sink

Nara records detail losses, investigation of titanic’ s demise.

Spring 2012, Vol. 44, No. 1

By Alison Gavin and Christopher Zarr

The Titanic during sea trials. (306-NT-1308-91560)

View in National Archives Catalog

Perhaps no other maritime disaster stirs our collective memory more than the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912.

The centennial of this event brings to mind the myriad films, books, and electronic media the disaster engenders. The discovery of the ship at the bottom of the sea in the 1980s brought to view intriguing artifacts.

The National Archives holds Titanic -related "treasures" as well: Senate investigation records, documents pertaining to Titanic passengers from limited liability suits, and congressional resolutions. These records tell the stories of the survivors in their own words.

When Titanic set sail from Southampton, England, for New York City on April 10, 1912, no one, especially its builders, dreamed of its demise. The ship's owners, the White Star Line, boasted of the size and stamina of the largest passenger steamship built until that time. Yet the "ship that could never sink" sank less than three hours after the crew spotted an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on April 14. Of the 2,223 people aboard, 1,517 perished.

The lack of sufficient lifeboats was chief among the reasons cited for the enormous loss of life. While complying with international maritime regulations ( Titanic carried more than the minimum number of lifeboats required), there were still not enough spaces for most passengers to escape the sinking ship.

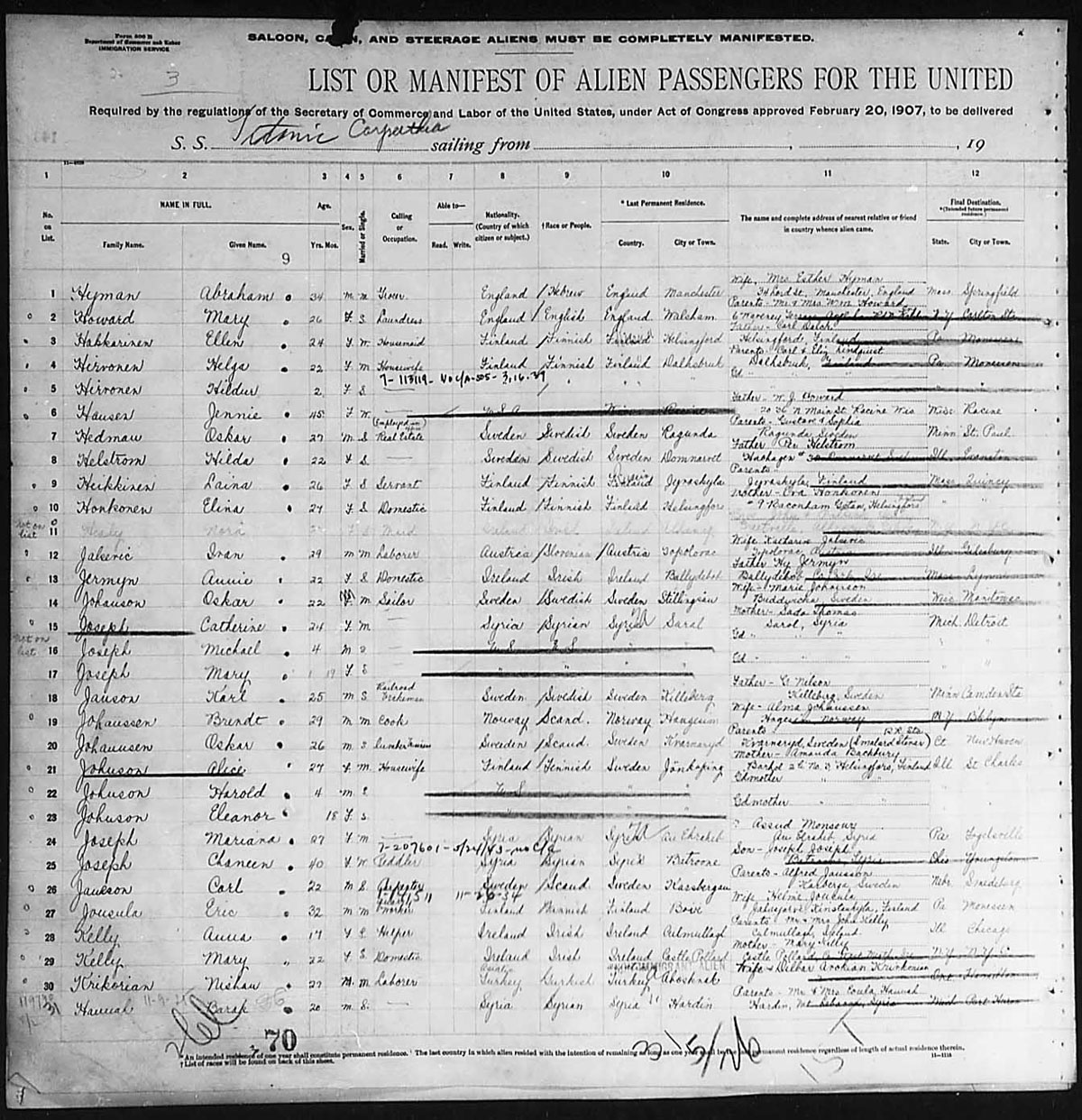

The Carpathia was the lone ship to respond to Titanic' s distress signals, risking a field of icebergs in a daring rescue. The Carpathia' s passenger manifest includes the names of the 706 persons it picked up from Titanic' s lifeboats on the morning of April 15, 1912. The manifests collected by the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization list 29 categories of questions asked of all persons entering the United States, from birthplace to where the person would be staying in the United States.

The Titanic Relief Fund, set up by Ernest P. Bicknell in his capacity as director of the American Red Cross, raised $161,600.95 for Titanic survivors and families of the victims. (the British component raised $2,250,000). According to Red Cross "Titanic Relief Fund" documents in the National Archives:

The Director and other representatives of the Red Cross Committee were present when the Carpathia landed its passengers [at the port of New York on April 18]. The office of the committee was opened on the following morning, equipped with telephone service, printed stationery, the necessary blank forms and record cards, and with a staff of visitors and clerks supplied by the Charity Organization Society. Within two days substantially all the survivors of the third cabin passengers and many of the second cabin passengers had been visited and interviewed in their places of temporary shelter or at the Committee's Office. . . . This was extremely important. because comparatively few of the third cabin passengers remained in New York City.

A third-class (steerage) passenger's contract ticket for the White Star Line, similar to those used on the Titanic. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

The highest percentage of victims were steerage, or "third cabin" passengers, who were mainly poor immigrants coming to America. The ethical question of why first-class passengers were allowed to get into lifeboats ahead of those in second and third class became an issue for future investigation.

The unimaginable scale of the disaster led many people to write to the President of the United States. Dozens of letters came to President William H. Taft from citizens who were angered, inspired, or moved by the loss of the Titanic. They demanded an investigation into the sinking, shared ideas for the prevention of such disasters in the future, or expressed sympathy for the death of President Taft's military aide, Maj. Archibald Butt. Butt, one of Taft's closest friends, was returning from a six-week vacation aboard the Titanic, and his leave of absence papers and a copy of a letter of introduction from Taft to Pope Pius X are also in the National Archives.

Congressional Hearings Lead to Legislation, Regulations

Almost immediately after the disaster, a congressional hearing was convened on April 19, 1912. Extensive documentation of the Titanic' s voyage is contained within the proceedings of the U.S. Senate's "Titanic Disaster Hearings." The report's 1,042 pages document what a commerce subcommittee learned over its 17-day investigation of the causes of the wreck. The subcommittee's chairman, Senator William Alden Smith (R-Michigan), spoke fervently of why he wished to document the event quickly:

Our course was simple and plain–to gather the facts relating to this disaster while they were still vivid realities. Questions of diverse citizenship gave way to the universal desire for the simple truth. . . . We, of course, recognized that the ship was under a foreign flag; but for the lives of many of our own countrymen had been sacrificed and the safety of many had been put in grave peril, it was vital that the entire matter should be reviewed before an American tribunal if legislative action was to be taken for future guidance on international maritime safety.

The subcommittee interviewed 82 witnesses and investigated everything from the inadequate number of lifeboats to the treatment of passengers riding steerage to the newly operational wireless radio machines. Smith also wanted to know why warnings of icebergs had been ignored.

The Navy Hydrographic Office's daily memorandum notes both ice reports in the North Atlantic and the Titanic' s collision with an iceberg. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

One of the themes emerging from the " Titanic Disaster Hearings" is the excesses of the "Gilded Age"—wealth, power, and business in a newly technological world gone wild. The hearings were held in the glamorous Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in Manhattan. (Ironically, John Jacob Astor IV, who perished aboard the Titanic, had built the Astoria Hotel, which later became part of the Waldorf-Astoria.)

Opposite the senators sat the first witnesses, White Star's managing director J. Bruce Ismay and other company officials. Ismay was also president of the International Mercantile Marine Company, White Star's American parent company. He was vilified in the press as a monster, as one who had put his own life and safety before that of women and children as the lifeboats were launched.

Throughout the hearings, he remained confident, almost hubristic, regarding the ship's stamina under pressure. In explaining how Titanic' s disaster could have been averted, he stated simply, "If this ship had hit the iceberg stern on, in all human probability she would have been here to-day [the stern being the most reinforced part of the ship]."

Instead, he said, the iceberg made "a glancing blow between the end of the forecastle and the captain's bridge." He remained sentimental regarding the ship's demise. In the lifeboat, he rowed the opposite direction of the sinking Titanic: "I did not wish to see her go down. . . . I am glad I did not."

Ismay said the trip was a voluntary one for him, "to see how [the ship] works, and with the idea of seeing how we could improve on her for the next ship which we are building." He told the subcommittee, "We have nothing to conceal, nothing to hide." He was grilled again on the 10th day of the investigation, when he denied reports of speeding up the ship to "get through" fields of ice; other eyewitnesses, however, would contradict him.

Also interviewed the first day was Arthur Henry Rostron, the captain of the Carpathia. Rostron gave detailed information about the circumstances under which Titanic' s distress signals had been heard: the wireless operator was undressing for the night but still had his headphones on as the signal came across.

Rostron also related the details of how he prepared the Carpathia to receive the hundreds of survivors in the lifeboats. He came alongside the first lifeboat at 4:10 a.m. on April 15 and rescued the last at 8:30 a.m. He then recruited one of the Carpathia' s passengers, an Episcopal clergyman, to hold a prayer service of thankfulness for those rescued and a short burial service for those who were lost.

The Carpathia was the only ship to respond to the Titanic' s distress signals. The Carpathia' s manifest records the names of the 706 person it rescued from lifeboats on the morning of April 15, 1912. (Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85)

Rostron would later receive a special trophy as a symbol of gratitude from the survivors of the Titanic. It was presented to him by the legendary "Unsinkable Molly [Margaret] Brown," a wealthy Denver matron who assisted with the lifeboats. Rostron received many other memorials and a Medal of Honor from President Taft.

The outcome of the hearings was a variety of "corrective" legislation for the maritime industry, including new regulations regarding numbers of lifeboats and lifejackets required for passenger vessels. In 1914, as a direct result of the Titanic disaster, the International Ice Patrol was formed; 13 nations support a branch of the U.S. Coast Guard that scouts for the presence of icebergs in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

Survivors, Families Seek Millions from White Star

Beyond simply seeking corrective legislation to prevent future disasters, the survivors and the families of victims also sought redress for loss of life, property, and any injuries sustained. The limited liability law at the time, however, could restrict their claims significantly. The Titanic' s liability was protected by an 1851 law ("An Act to limit the Liability of Ship-Owners, and for other Purposes," 9 Stat. 635) designed to encourage shipbuilding and trade by minimizing the risk to owners when disasters occurred.

Under this law, in cases of unavoidable accidents, the company was not liable for any loss of life, property, or injury. If the captain and crew made an error that led to a disaster, but the company was unaware of it, the company's liability was limited to the total of passenger fares, the amount paid for cargo, and any salvaged materials recovered from the wreck. The 706 survivors and the families of the 1,517 dead therefore might be entitled to only a total of $91,805: $85,212 for passengers, $2,073 for cargo, and a $4,520 assessment for the only materials salvaged from the Titanic —the recovered lifeboats.

In October 1912, the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (more commonly known as the White Star Line) filed a petition in the Southern District of New York to limit its liability against any claims for loss of life, property, or injury. In this petition, the White Star Line claimed that the collision was due to an "inevitable accident." "In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship TITANIC" (A55-279) is a part of the National Archives holdings in New York City.

Profiles of the Titanic and its decks. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

The only way to remove limits on the company's liability would be to prove that the captain and crew were negligent and the ship's owners had knowledge of this fact.

Those individuals seeking payments slowly began to build their case against the White Star Line. They held that although the crew had received wireless messages about the presence of icebergs, the Titanic had maintained its speed, stayed on the same northern course, posted no additional lookouts, and failed to provide the lookouts with binoculars.

In addition, they faulted the White Star Line for not properly training the crew for evacuation, leading to the launching of partially filled lifeboats and the loss of even more lives. For these reasons, combined with the fact that the managing director of the White Star Line, Ismay, was on board the Titanic, claimants believed the liability should be unlimited.

After White Star filed its petition, several notices were placed in the New York Times between October 1912 and January 1913, asking people who claimed damages to prove their claims by April 15, 1913. Hundreds of claims totaling $16,604,731.63 came from people around the world. Claims were divided into four groups: Schedule A: Loss of Life, Schedule B: Loss of Property, Schedule C: Loss of Life and Property, and Schedule D: Injury and Property.

The Schedule D claims for injuries and property detail the harrowing experiences of many survivors of the Titanic. In nearly 50 claims, survivors describe how they lived through the disaster and the physical and mental injuries they sustained.

Anna McGowan of Chicago, Illinois, was unable to get on a lifeboat and jumped from the Titanic onto a lifeboat and sustained permanent injuries from the fall, shock, and frostbite. The experience left her in a state of "nervous prostration" (most likely something similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD) and unable to provide for herself.

Survivors of the Titanic disaster aboard a lifeboat on April 15, 1912. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

Patrick O'Keefe of Ireland also jumped overboard to save his life, but he remained in the cold Atlantic waters for hours before being rescued by lifeboat B.

Bertha Noon of Providence, Rhode Island, asked for more than $25,000 due to injuries she sustained after being pushed onto a lifeboat and being exposed to the cold for several hours before being rescued by the Carpathia . Her injuries included an injured back and spine that left her "unable to wear corsets," severe nervous shock, a "misplaced womb," and a recurring congestion in her head and chest that left her delirious and unconscious for days at a time.

Though the Schedule A claims filed by family members for loss of life did not include first-hand accounts of the accident, they document tragic losses of entire families. Finnish immigrant John Panula was preparing for a reunion with his family in Pennsylvania when his wife and four children died on the Titanic. The Skoogh family with their four children Carl, Harold, Mabel, and Margaret Skoogh (ages 12, 9, 11, and 8 respectively) were returning to the United States aboard the Titanic.

Claims for Losses Reveal Class Differences

The loss of life claims also reveal the variety of values assigned to a human life. While Alfonso Meo's widow, Emily J. Innes-Meo, asked for only £300 (approximately $1,500 at the time), Irene Wallach Harris, the widow of Broadway producer and theater owner Henry B. Harris, sought $1 million in her claim. Some of the documents state the ages and annual salaries of the deceased to justify the amounts they were seeking in their claims. The most detailed claim involved the $4,734.80 claim filed by the family of 41-year-old James Veale:

That the said James Veale was by profession a granite carver; that he was earning at the time of his death $1,000 per year or more. That according to the Northampton Table of Mortality, the said James Veale, deceased probably would have lived, except for his death aforesaid, 11.837 years more; that the said James Veale did not expend upon himself more than $600 a year; that his personal estate has been damaged in the sum of $400 per year during the period of 11.837 years and to the extent of $4,734.80 by reason of the aforesaid breach of contract committed by the petitioner herein as aforesaid.

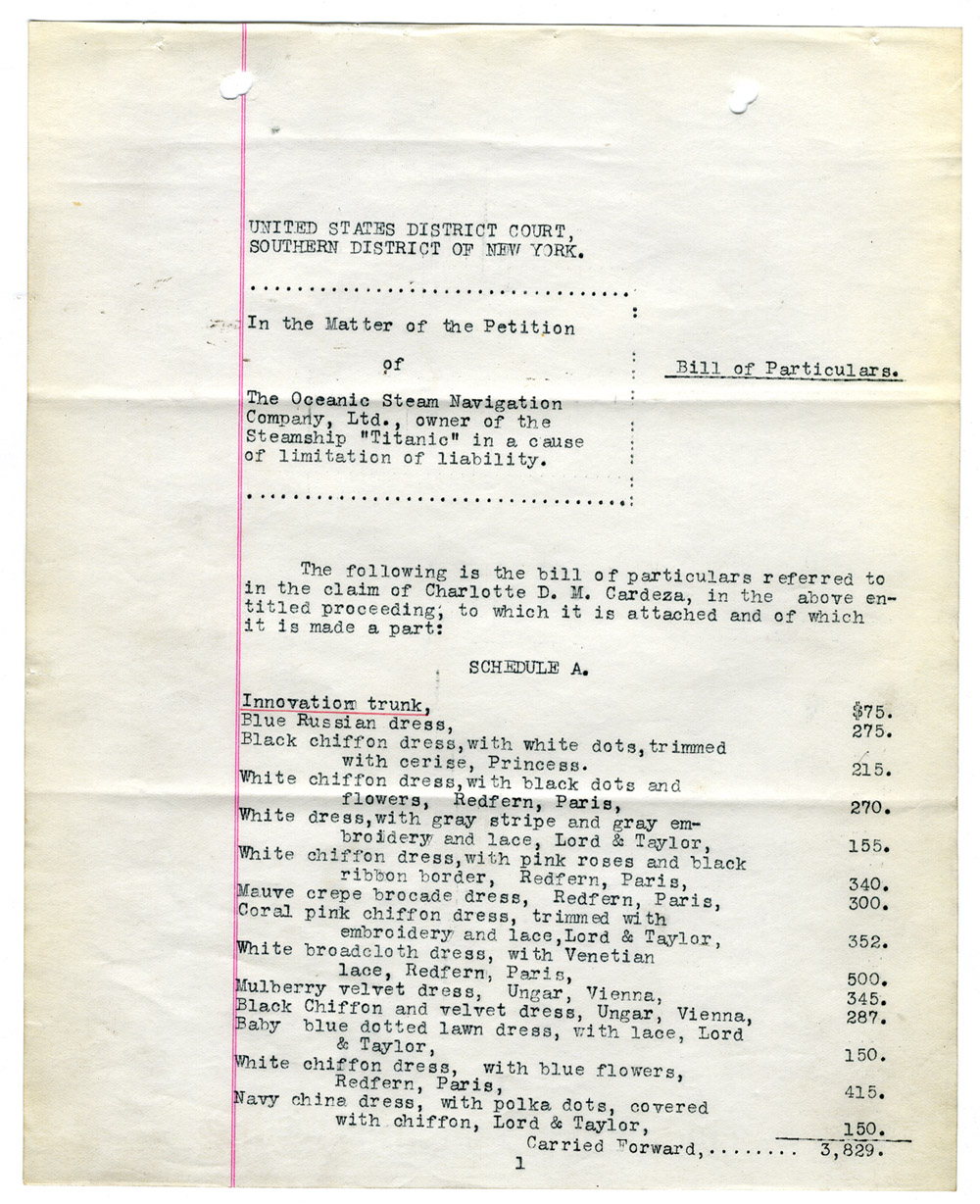

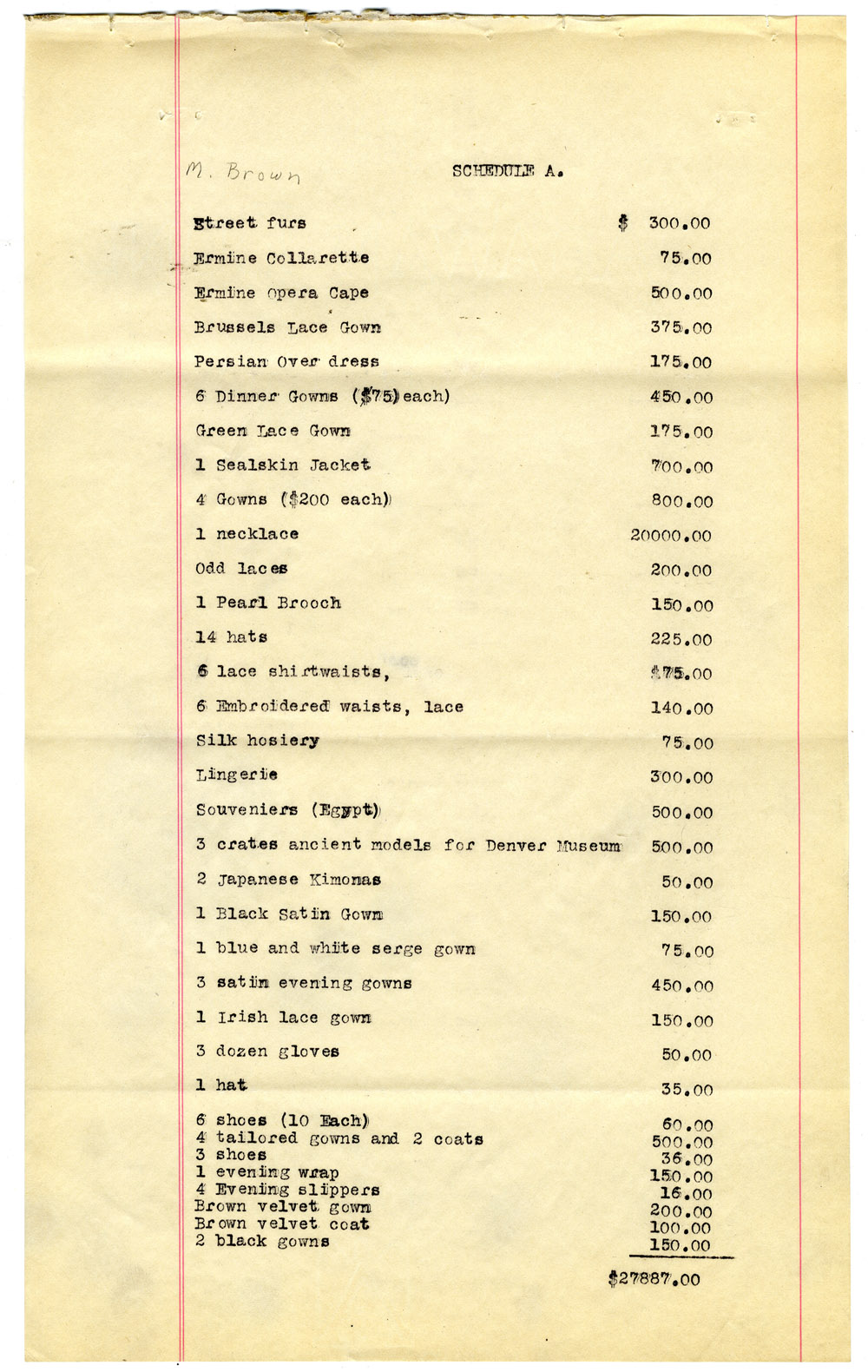

Charlotte Drake Cardeza's claim is the largest and most detailed claim among the Schedule B claims for loss of property. In nearly 20 pages, she itemized the lost contents of 14 trunks, 4 suitcases, and 3 crates. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

The claims also reveal the vast class differences apparent among the passengers of the Titanic. This is most apparent in the Schedule B claims for loss of property. The most detailed and largest property claim belongs to socialite Charlotte Drake Cardeza, who occupied the most expensive stateroom on the ship. After surviving the sinking of the Titanic aboard lifeboat 3, Cardeza filed a claim for the lost contents of her 14 trunks, 4 suitcases, and 3 crates of baggage (a total of at least 841 individual items) for a sum of $177,352.75. The nearly 20-page itemized claim includes objects such as her 6 7 / 8 -carat pink diamond ring valued at $20,000. On the other end of the spectrum, Yum Hee of Hong Kong filed a claim for $91.05. His most expensive item: a suit of clothes valued at £2.5 (approximately $12.50 at the time).

From the claims for loss of property, we also discover that Margaret ("Molly") Brown's three crates of ancient models destined for the Denver Museum, Col. Archibald Gracie's documents concerning the War of 1812, and over 110,000 feet of motion picture film owned by William Harbeck are all now at the bottom of the Atlantic. The most expensive individual item lost during the sinking was H. Bjornstrom-Steffanson's four-foot-by-eight-foot oil painting La Circasienne Au Bain by Blondel, valued by him at $100,000.

Schedule C claim 72 was filed on July 24, 1913, by Mabelle Swift Moore, widow of businessman Clarence Moore. Moore had been a member of a Washington, DC, brokerage firm W. B. Hibbs and Company and owned extensive real estate. A "master" of the hunt, he had been in England looking for a pack of 50 hounds. (The dogs, however, were not carried on the Titanic.) Mrs. Moore sued for $510,000.

Survivors Give Eyewitness Accounts of the Sinking

Though the White Star Line filed its petition in October 1912 and individual claims were due by April 1913, hearings were not held in the Southern District of New York until June 1915. Depositions filed with the court throughout 1913 and 1914 provide conflicting reports on blame for the disaster.

In June 1914, White Star Line's Ismay was questioned about the speed of the Titanic, its lifeboats, the lookout, and other issues that may have contributed to the disaster. Throughout his testimony, Ismay restated many of the same opinions given during the congressional hearing—that all decisions were made by Capt. Edward Smith and he was onboard to consider passenger accommodation improvements for the White Star Line's next ship, the Britannic.

The "Unsinkable Molly Brown" filed a claim for lost property that included an extensive collection of gowns, hats, and jewelry as well as "ancient models for Denver Museum." (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

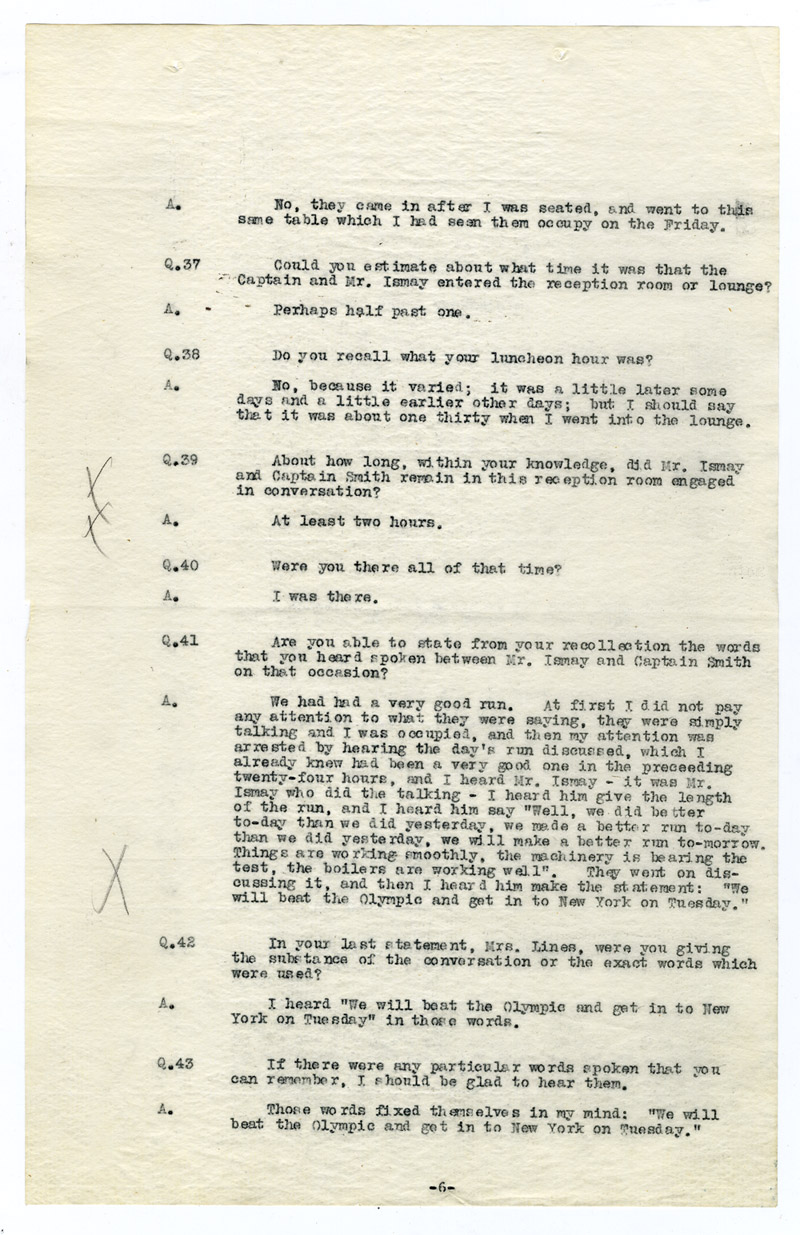

Statements by two of the survivors, Elizabeth Lines and Emily Ryerson, seemed to contradict Ismay's statements. Lines declared that she overheard parts of a two-hour conversation between Captain Smith and Ismay on Saturday, April 13. Sticking in her mind was Ismay's statement, "We will beat the Olympic and get in to New York on Tuesday," meaning they would arrive one day earlier than originally planned. The following day, Ryerson recalled Ismay holding a message and stating to her that "We are in among the icebergs." Despite this, he told her that they would be starting up extra boilers that evening to surprise everyone with an early arrival.

Other depositions filed by survivors give us eyewitness accounts to the dramatic and tragic final moments aboard the Titanic. Ryerson described the bitter cold of that April night before being told by a fellow passenger to put on her life belt. Though she described the initial scene on the boat deck as without confusion, the situation changed quickly. Passengers were thrown by crew into the lifeboats; Ryerson even describes falling on top of someone. After lifeboat no. 4 was loaded with 24 women and children (far below the 65 it could hold), it was lowered toward the water. Before being fully lowered, the lifeboat jammed, and men swarmed into the boat, which was intended for women and children only. After being lowered, the survivors and crew began to row for their lives, fearing that the sinking Titanic might suck them down with it. Later on that night, near dawn, Ryerson's boat returned to the site of the sinking and began rescuing some 20 survivors.

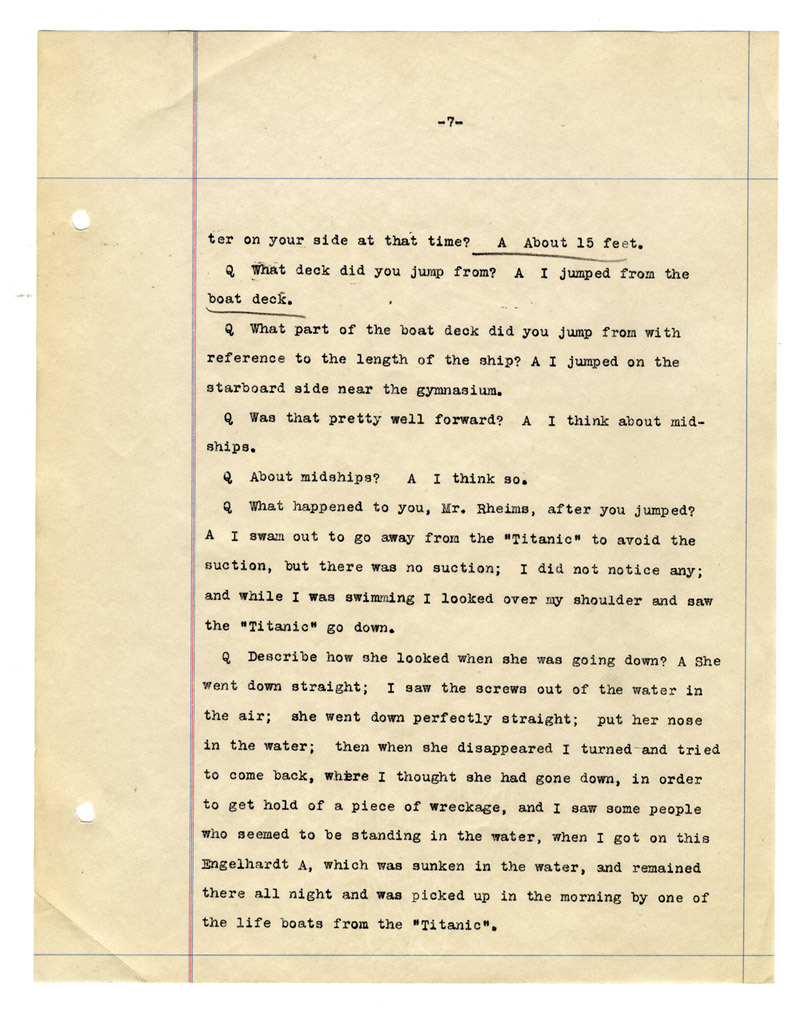

Among those rescued survivors was George Rheims, who remained for some five hours in waist-high water on a partially submerged collapsible lifeboat. In his deposition he recounts how hours earlier, after Rheims noticed "a slight shock" when returning from the bathroom, he looked out the nearest window and saw a massive white iceberg pass by. He then reported witnessing several lifeboats launching that were between half and three-quarters full. He also described seeing men scrambling onto lifeboats as they were lowered and hearing pistols being shot during his last hour aboard the ship. In the final minutes before Titanic disappeared into the depths, Rheims jumped into the cold waters and waited for his rescue.

Over several days in June and July 1915, testimony continued. Negotiations carried on outside of court led to a tentative settlement with nearly all of the claimants in December 1915. The settlement was for a total of $664,000 to be divided among the claimants. A final decree, signed by Judge Julius M. Mayer in July 1916, held the company guiltless of any privity and knowledge and not liable for any loss, damage, injury, destruction, or fatalities.

In a page from her testimony, passenger Elizabeth Lines recounts overhearing Bruce Ismay remark to Captain Smith on the speed of the ship's crossing, saying that they will beat the Olympic and get in to New York on Tuesday. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

George Rheims recalled that as he swam away from the sinking Titanic, he looked back and saw the screws [propellers] out of the water in the air; she went down perfectly straight. He was rescued the next morning. (Records of District Courts of the United States, RG 21)

The Titanic' s tragic story fascinated people both at the time of the disaster and for generations after. For more than 70 years, the exact location of the ship's remains was unknown. On September 1, 1985, a joint American and French expedition team found the vessel under more than 12,400 feet of water off the coast of Newfoundland. On November 21 of the same year, Rep. Walter Jones, Sr., of North Carolina, chairman of the House Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, submitted a report to accompany House Resolution 3272. It recommended that the shipwreck Titanic be designated "as a maritime memorial and to provide for reasonable research, exploration, and, if appropriate, salvage activities."

Perhaps in the end, the 1986 Memorial Act sums it up best by stating, where marine resources are concerned, at least, "we must maintain a sense of perspective regarding man's abilities and nature's powers." Nature's power, in the form of an iceberg in the frigid north Atlantic Ocean one April night in 1912, seems to impress us all the more 100 years later.

Alison Gavin received her M.A. in history from George Mason University in 2004; she was the 2003 Verney Fellow for Nantucket Studies. She has worked in the National Archives since 1995, and her work has appeared in New England Ancestors, Historic Nantucket, Quaker History, and Prologue.

Christopher Zarr is the education specialist for the National Archives at New York City. He works with teachers and students to find and use primary sources in the classroom.

Note on Sources

Learn more about:

- Other Titanic records online

- Stories from the Titanic on the Prologue blog

- The sinking of the Christmas tree ship in Lake Michigan

Additional research for this article was conducted by William Roka at the National Archives at New York City.

The Carpathia' s passenger manifests listing survivors of the Titanic are in Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, RG 85, at the National Archives Building (NAB), Washington, DC. They have been microfilmed as T715, Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1897–1957, roll 1883.

The letters to President Taft regarding the disaster are in "Letters Sent by President Taft to the Department of Commerce and Labor," Entry 15, General Records of the Department of Commerce, Record Group (RG) 40, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP).

Archibald Butt's leave of absence papers and a copy of his letter of introduction to Pope Pius X are in Records of the Adjutant General's Office, RG 94, NAB.

The largest and most far-reaching of the documents NARA has concerning the sinking of Titanic (at 1,176 pages) can be found in the United States Congressional Serial Set (serial 6167): U.S. Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce, " Titanic " Disaster: Hearings before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce United States Senate, pursuant to S. Res. 283 directing the Committee on Commerce to investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star Liner " Titanic ," S.Doc. 726, 62nd Congress, 2nd sess., 1912 (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1912), Publications of the U.S. Government, RG 287, NACP.

A more accessible source for the Senate hearings, at only 571-pages, is The Titanic Disaster Hearings: The Official Transcripts of the 1912 Senate Investigation, edited by Tom Kuntz (New York: Pocket Books, 1998). It gives accounts of the 17 days of hearings, an introduction and epilogue, an appendix, a list of witnesses, and a digest of testimony.

The records from the limited liability suits are in the case file "In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship TITANIC"; Admiralty Case Files Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group 21; National Archives at New York City.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Digital Twin’ of the Titanic Shows the Shipwreck in Stunning Detail

Researchers hope new 3-D images will provide clues about what happened to the ocean liner when it sank on its maiden voyage in 1912.

By April Rubin

An ambitious digital imaging project has produced what researchers describe as a “digital twin” of the R.M.S. Titanic, showing the wreckage of the doomed ocean liner with a level of detail that has never been captured before.

The project, undertaken by Magellan Ltd., a deepwater seabed mapping company, yielded more than 16 terabytes of data, 715,000 still images and a high-resolution video. The visuals were captured over the course of a six-week expedition in the summer of 2022, nearly 2.4 miles below the surface of the North Atlantic, Atlantic Productions, which is working on a documentary about the project, said in a news release.

The researchers used two submersibles, named Romeo and Juliet, to map “every millimeter” of the wreckage as well as the entire three-mile debris field. Creating the model, which shows the ship lying on the ocean floor and the area around it, took about eight months, said Anthony Geffen, the chief executive and creative director of Atlantic Productions.

“We’re now going to write the proper science of the Titanic,” he said.

Previous images of the wreckage, which was found less than 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland in 1985, suffered from low light and murky water. The new images have effectively removed the ocean water, allowing the wreckage to be viewed in “extraordinary detail,” Atlantic Productions said, noting that a serial number can be seen on a propeller.

The Titanic, the largest passenger ship built at the time, sank on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on its maiden voyage. Many details of the disaster, in which more than 1,500 people perished, have remained a mystery ever since.

The models offer new details about the shipwreck that hadn’t previously been known, Mr. Geffen said. For example, he said, one of the lifeboats was blocked by a jammed metal piece and couldn’t be deployed.

The submersibles captured images of personal artifacts, such as watches, top hats and unopened champagne bottles, that were strewn across the debris field. Experts hope they will be able to match personal items to Titanic passengers using artificial intelligence, Mr. Geffen said. He added that people someday would also be able to witness the shipwreck through virtual reality and augmented reality.

“In accordance with tight regulations in place, the wreck was not touched or disturbed,” Atlantic Productions said, adding that the site was treated “with the utmost of respect, which included a flower-laying ceremony in memory of those who lost their lives.”

“This was a challenging mission,” Richard Parkinson, Magellan’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “In the middle of the Atlantic we had to fight the elements, bad weather and technical challenges to carry out this unprecedented mapping and digitalization operation of the Titanic.”

April Rubin is a breaking news reporter and a member of the 2022-2023 New York Times fellowship class. More about April Rubin

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Significance

- About The Royal Statistical Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The first graph, who was g. bron, some modern uses, past and future.

- < Previous

Visualising the Titanic Disaster

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Michael Friendly, Jürgen Symanzik, Ortac Onder, Visualising the Titanic Disaster, Significance , Volume 16, Issue 1, February 2019, Pages 14–19, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2019.01229.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The sinking of the Titanic has inspired books, movies and documentaries. But it has also motivated data visualisation designers to tell the story of the tragedy in new ways. Michael Friendly, Jürgen Symanzik and Ortac Onder review the first graph of the disaster and some recent history

T he sinking of the RMS Titanic is one of the most storied shipwrecks in maritime history. Touted as the ultimate in transatlantic travel and said to be “unsinkable”, the Titanic collided with an iceberg on 14 April 1912 on her maiden voyage and sank shortly thereafter on 15 April, killing 1502 out of 2224 passengers and crew. The sinking of the Titanic is not the largest in terms of lives lost. But it is the one that has been documented most thoroughly – in government reports and personal accounts of survivors, and in numerous books and several popular movies.

This is one legacy of the Titanic disaster, but it left another: a wealth of data, comprising details of passengers and crew, many with names, ages, passenger class, and even cabin numbers for those in first and second class.

We recently discovered an early and relatively unknown graph showing survival among the Titanic passengers and crew, published less than one month after the disaster. This graph had a surprisingly modern look. It prompted us to review the history of this graph and the variety of uses to which the Titanic data have been put in the two decades since the data set became available in machine-readable form.

The Sphere was a popular British illustrated weekly newspaper, published by the Illustrated London News Group from January 1900 until June 1964. It was dedicated to worldwide reporting on popular issues. On 4 May 1912, only three weeks after the Titanic disaster, it published a chart (Figure 1 , page 16) by the graphic artist G. Bron using data released the week before by the House of Commons.

G.Bron's chart of “The Loss of the ‘Titanic'”, from The Sphere , 4 May 1912. Each subgroup is shown by a bar whose area is proportional to the numbers of cases. © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans.

Bron's graph shows the breakdown of survival among the passengers and crew – by passenger class, gender and age (comparing adults and children) – in what is clearly an early innovation in data display. It combines back-to-back bar charts for those who lived and those who perished, using area of the bars to convey the actual numbers. Within the passenger classes, the numbers and bars are subdivided by gender for adults, while children are shown as a separate group. It also includes two similar summary panels, showing the totals for all passengers and for all passengers and crew.

Today, we might describe this as an early form of a mosaic plot, or as an area-proportional back-to-back array of bar charts. Whatever name we give, it deserves to be admired as an exceptional early example of data visualisation and a tribute to the skills of the illustrator.

G. Bron was a prolific technical illustrator who worked for The Sphere , the Illustrated London News and similar publications between about 1910 and 1925. Today, he would be called a data-graphic or info-vis designer, one far ahead of his time. Little about him was previously known, not even his first name. A search in the British Newspaper Archive ( bit.ly/2Rzv5dm ) turned up over 20 examples of his work, most published in The Sphere . In the course of writing this article we discovered that G. Bron was most likely the pseudonym adopted by William B. Treeby, born in London, but further biographical details are still sketchy (see supplementary material at bit.ly/titanicvis ).

Bron's use of back-to-back proportional bar charts to show death versus survival was a stroke of graphic genius

By and large, Bron's illustrations were graphic stories, designed to convey an interesting but possibly complex topic visually, in ways in which mere words and numbers could not compete. It is difficult to know what led him to produce his remarkable chart of the Titanic . Sometime between the sinking on 15 April and the publication of his Sphere graph on 4 May, he became aware of a numerical table classifying passengers and crew that would shortly be published by the House of Commons. We can imagine that he looked at this and asked himself how he could make it comprehensible to his readers. His use of back-to-back proportional bar charts was novel and a stroke of graphic genius. Just a glance showed that, overall, two-thirds of the passengers and crew perished. The separate conditional panels for class showed directly to the eye that survival was greatest in first class and least among the crew. The reader could “drill down” to examine the breakdown by gender and age within each class.

The primary sources of data on the Titanic derive from official inquiries launched in Britain and the USA. (Complete documents can be found at titanicinquiry.org .) Shortly after the disaster, the British Parliament authorised the British Board of Trade Inquiry with Lord Mersey as chair. The committee interviewed over 100 witnesses over 36 days of hearings. Their report, issued on 30 July 1912, contained extensive tables of passengers and crew, broken down by age group, gender, class and survival, as well as details on the launching of the 20 lifeboats. In April–May 1912 a similar inquiry was initiated in the US Senate which interviewed 82 witnesses over 18 days. Among other things the report (over 1000 pages) contained lists of the names and addresses of most passengers and crew.

As far as we are aware, the first public data set appeared in 1995 in an article by Robert Dawson, titled “The ‘Unusual Episode’ Data Revisited”, in the Journal of Statistics Education . 1 Its classroom use was illustrated by an exercise in statistical thinking, where students were shown tables of deaths and death rates – classified by economic status, age and gender – for an “unusual episode” (without context) and asked to reason about what the causes might have been. The data set contains 2201 observations and the variables Class, Age, Sex and Survived.

In September 1995, Phillip Hind launched encyclopedia-titanica.org , the first publicly available database on all passengers and crew aboard the ship. At the time, it was the only reasonably complete individual list giving details of name, actual age, profession, cabin number, lifeboat number, and so forth. Two surviving canine pets (one named Sun Yat Sen) were also listed. 2 The website now includes photos and biographies on many of the passengers and crew.

Popular interest in the Titanic surged with the release of James Cameron's movie in November 1997. Immediately following this, Random House released a boxed set, Titanic: The Official Story , containing the Mersey report and facsimiles of 18 original documents from London's Public Record Office. 3 These included the Titanic deck plans, the final telegram sent from the ship just prior to sinking, newspaper articles excoriating the White Star Line for criminal negligence, lists of deaths recorded in official logs, and so on. It is not explicitly clear what the goal or purpose was, but these materials serve as a model case for courses in history of statistics and archival research.

The Titanic data, taken from Dawson, made their first public appearance in a software package in R, version 0.90.1, in December 1999, expressed as a four-way contingency table of counts, classified by Class, Age, Sex and Survived. A variety of other data sets are available in contributed R packages, including TitanicSurvival (in the car package), which gives details (name, sex, age, class, survived) on 1309 passengers, and Lifeboats (in the vcd package), which gives data on the composition and launch times of the lifeboats. Passenger data from the Titanic , split into training and test samples, is also used in a Kaggle prediction competition ( bit.ly/2RxcwGU ).

The significance of the disaster and the availability of information regarding the passengers and crew made the Titanic data attractive for various uses. The range of disciplines gives a sense of the appeal of these data as a compelling example of popular interest, of a novel graphical method or illustration of some statistical technique. The context makes it easy to tell an interesting story to illustrate a new method or graph.

In statistics, narrowly defined, the data have been used to illustrate graphical methods for categorical data and their use as a visualisation method for log-linear models and related generalised linear models. Recursive partitioning methods (also known as classification and regression trees, or CART models) is another area where the Titanic data provide an easily understood concrete example, and this has led to tree-based visualisations.

In a wider scope, encompassing computer science and data science, with an emphasis on predictive modelling and cross-validation, the Titanic data provide an important test case; while in the InfoVis community, the data provide a challenge – and opportunity – for graphic designers to try to tell the story of the disaster in a single sheet, containing words, numbers, pictures and data visualisations.

What follows is a selection of a few highlights to illustrate the themes described above.

Mosaic-type plots

Bron's initial graphic idea, to show deaths and survival on the Titanic , broken down by passenger class, gender and age group, was brilliant at the time, and perhaps underappreciated in the history of data visualisation. He was on to something important: how to display the proportions of survivors, classified by the other variables he had available. His solution anticipated modern methods.

In the 1990s two new ideas for graphical analysis of categorical data arose for this problem. The Titanic data provided great examples because they gave a context and a story to appreciate these new methods.

First, mosaic plots, proposed by Hartigan and Kleiner, provided a new graphic method for visualising multivariate frequency tables, in a single view rather than a collection of oneway or two-way diagrams. 4 The essential idea was a mosaic of rectangles (“tiles”), with the area of each made proportional to the cell frequency. Friendly connected these with log-linear models by shading the cells in relation to residuals in a given model. 5 , 6 For example, Figure 2 shows the result of fitting two models to the Titanic data. The left-hand panel shows the fit of the model with the symbolic formula [CGA][S], which asserts that Survival ([S]) is independent of Class, Gender and Age jointly. This is the baseline, null model. The pattern of shading (blue for positive residuals, red for negative) shows that important associations remain unaccounted for: that is, one or more of Class, Gender and Age affects Survival. The right-hand panel shows the fit of the model [CGA][CS][GS][AS], which allows “main effect” associations of each of Class, Gender and Age with Survival. This model fits much better, but still shows significant lack of fit. The pattern of residuals here suggests some interactions are present: adding the term [GAS] would allow an interaction of Gender and Age (“women and children first”); adding the association [CGS] would allow Survival to depend on the combinations of Class and Gender.

![research articles on titanic Mosaic plots for two log-linear models fitted to the Titanic data. Left: joint independence model [CGA][S]; right: main effects model [CGA][CS][GS][AS]. Source: author graphic, based on Friendly (1999).6](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jrssig/16/1/10.1111_j.1740-9713.2019.01229.x/2/m_sign_16_1_14_fig-2.jpeg?Expires=1719030637&Signature=hZq65~ttfhwFWPcaDQcMSdZcJGA0n1WPRlsmOh~SlPU6Qicakt9-4WrSvLm1E6VuUZ5TMh4~uppDeEEu8WHOksms~iQK5BIT0DwRFAc6Kd9C1U7tJORMHRT1Onm7nGFxBnJg0T-ye-HoG7m9vSzYHGbne9U-5PwVkFompxD5UnRXO4kAVg5LTg4O4ks9lw4YR5takl0Cz02r~M9E~A6BKqcuCbaVKRUb67~ad2UGa6JuIMO8OSPg9pELAMD~4FufAErVvZ3f44QOW1T4fDJwEok3OsGZQaBo9X7a0Fdo7sZVnNn~EanQq-ZXfIgPB~dYo-CSAw-o-LAXPPyjBZDWYw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Mosaic plots for two log-linear models fitted to the Titanic data. Left: joint independence model [CGA][S]; right: main effects model [CGA][CS][GS][AS]. Source: author graphic, based on Friendly (1999). 6

Second, interactive software for visualising and manipulating multivariate contingency tables was developed. MANET 7 and MONDRIAN 8 from the Augsburg lab are notable here. Hofmann illustrated how selecting a category of one variable (Survived) highlighted those cases in all other views. 9 Valero-Mora et al . used the Titanic data to illustrate ViSta , a system combining multiple interacting windows, using both log-linear models and multiple correspondence analysis. 10

Figure 3 shows a double-decker plot, a variation of a mosaic plot in which the tiles for all predictors (Class, Gender and Age) are split horizontally and the response variable (Survived) is split vertically. 11 In this type of plot, the widths of the bars are proportional to the joint frequencies of C, G, and A. When each bar is split vertically by Survived, the heights of the black bars are proportional to the conditional probabilities of S given C, G, and A. If Survival were independent of all predictors (the model [CGA][S] shown in the left panel of Figure 2 ), the black bars would all have the same height. Note that showing the bars for survivors and those who perished back-to-back would give something similar to Bron's chart.

Double-decker plot of the Titanic data. Each bar has an area proportional to the frequency in the table. The proportion that survived is shaded black. Source: author graphic, recreated from Meyer et al . 12

Tree diagrams

Cross-classified data can also be displayed as tree diagrams of various types, with branches corresponding to splits of the categories for variables in some order. Tree-maps are a simple example, similar to mosaic plots in that they also display a measure of size by areas of rectangles. 13

Other graphical methods The Titanic data served to illustrate, or even motivate, a wide variety of graphical and analytic methods. A few are mentioned in this article, but more can be found online at bit.ly/titanicvis , including Venn diagrams, trilinear plots and nomograms.

A more powerful use arises in connection with classification trees as models for an outcome variable such as survival. For a binary response, these are similar to a series of logistic regression models, where predictors are chosen to maximise predictive accuracy at each step. Pruning methods and cross-validation are used to control model complexity and minimise out-of-sample classification error. Varian was among the first to use the Titanic data for this purpose. 14

Figure 4 gives the result of fitting a conditional inference tree (“ctree”) predicting survival from sex, class, age and a measure of family size (sibsp = number of siblings plus spouse aboard). The first node splits the data by sex. The second divides by class. The third node (in the right branch) splits males by age, and those aged 9 and under are further split by sibsp. The bars at the bottom show the survival rate in each terminal node. As opposed to log-linear models and generalised linear models, classification trees are somewhat more intuitive when shown visually, and have the additional advantage that what might be complex interaction terms in linear models can be easily fitted by successive splits on the branches to improve prediction.

Graphic representation of a conditional inference tree, predicting survival from sex, passenger class, age and family size. 14 © American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the Journal of Economic Perspectives .

Information visualisation

Following in the footsteps of Bron, modern graphic designers continue to be inspired by the tragedy of the Titanic and challenge themselves to tell the story of the disaster in ways that are both visually appealing and provide sufficient details. Unlike statistical graphs which usually focus on just one aspect, an information graphic often attempts to tell the entire story all on one sheet, as in a poster presentation.

The best example we have found of this genre is the graphic produced by Andrew Barr and Richard Johnson for the National Post (Figure 5 , and bit.ly/2RyjdbL ). This illustration strikes us as a tour de force of visual storytelling: numbers, words and pictures (both images and graphs) are woven seamlessly into a narrative. The top portion contains back-to-back bar plots of the passengers by age and class, showing the age distributions of those who survived and those who died, with pie charts summarising survival by class. It uses colours keyed to the locations of cabins for the classes in the dominant graphic of the ship. The bottom portion shows the loading of the lifeboats in the order they were launched, shaded to show the proportion of seats that were filled. It is clear that those launched early and those launched just before the ship sank were only partially filled. Other charts at the lower right give the death rates by gender and class and by nationality of the passenger. A text box gives an interpretation of survival, including the ideas of “women and children first” and the declining survival according to class.

Infographic by Barr and Johnson ( bit.ly/2RyjdbL ) telling a graphic story of survival on the Titanic . Notable is the integration of rich numerical information shown in graphs with images providing context and visual explanation. Material republished with the express permission of: National Post, a division of Postmedia Network Inc.

The sinking of the Titanic was surely a tragedy, but, unlike other historical events resulting in great loss of life, it left behind detailed information on the individuals involved – both victims and survivors – whose stories attracted wide interest. Bron's 1912 chart should be appreciated as an attempt at visual explanation far ahead of its time: the idea that survival could be understood through graphic displays.

We started this project with the discovery of Bron's chart, and the thought that it would be useful to collect and catalogue the various ways in which the Titanic data had been depicted in graphs over the past century. We were pleasantly surprised by the wide range of graphical methods and other applications we found. This attests to the compelling nature of the Titanic disaster and to the desires of modern graphical developers and designers to illustrate their methods and skills by continuing to tell the Titanic story. We believe that the Titanic data still have much to offer to graphic designers and visual storytellers.

Dawson , R. J. M. G. ( 1995 ) The “unusual episode” data revisited . Journal of Statistics Education , 3 ( 3 ).

Google Scholar

Friendly , M. ( 2000 ) Visualizing Categorical Data . Cary, NC : SAS Institute .

Google Preview

Anonymous ( 1997 ) Titanic: The Official Story: April 14–15, 1912 . New York : Random House .

Hartigan , J. A. and Kleiner , B. ( 1981 ) Mosaics for contingency tables . In W. F. Eddy (ed.), Computer Science and Statistics: Proceedings of the 13th Symposium on the Interface (pp. 268 – 273 ). New York : Springer-Verlag .

Friendly , M. ( 1994 ) Mosaic displays for multi-way contingency tables . Journal of the American Statistical Association , 89 , 190 – 200 .

Friendly , M. ( 1999 ) Extending mosaic displays: Marginal, conditional, and partial views of categorical data . Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics , 8 , 373 – 395 .

Hofmann , H. , Unwin , A. and Theus , M. ( 1997 ) MANET (software application) . http://www.rosuda.org/MANET/

Theus , M. ( 2002 ) Interactive data visualization using Mondrian . Journal of Statistical Software , 7 ( 2 ). http://www.jstatsoft.org/v07/i11/

Hofmann , H. ( 1998 ) Simpson on board the Titanic? Interactive methods for dealing with multivariate categorical data . Statistical Computing & Statistical Graphics Newsletter , 9 , 16 – 19 .

Valero-Mora , P. M. , Young , F. W. and Friendly , M. ( 2003 ) Visualizing categorical data in ViSta . Computational Statistics & Data Analysis , 43 , 495 – 508 .

Hofmann , H. ( 2001 ). Generalized odds ratios for visual modeling. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics , 10 , 628 – 640 .

Meyer , D. , Zeileis , A. and Hornik , K. ( 2006 ) The strucplot framework: Visualizing multi-way contingency tables with vcd . Journal of Statistical Software , 17 , 1 – 48

Shneiderman , B. ( 1992 ) Tree visualization with tree-maps: A 2-D space-filling approach . ACM Transactions on Graphics , 11 ( 1 ), 92 – 99 .

Varian , H. R. ( 2014 ) Big data: New tricks for econometrics . Journal of Economic Perspectives , 28 ( 2 ), 3 – 28 .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1740-9713

- Print ISSN 1740-9705

- Copyright © 2024 Royal Statistical Society

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A remarkable new view of the Titanic shipwreck is here, thanks to deep-sea mappers

Rachel Treisman

Scientists were able to map the entirety of the shipwreck site, from the Titanic's separated bow and stern sections to its vast debris field. Atlantic/Magellan hide caption

Scientists were able to map the entirety of the shipwreck site, from the Titanic's separated bow and stern sections to its vast debris field.

A deep sea-mapping company has created the first-ever full-sized digital scan of the Titanic, revealing an entirely new view of the world's most famous shipwreck.

The 1912 sinking of the Titanic has captivated the public imagination for over a century. And while there have been numerous expeditions to the wreck since its discovery in 1985, its sheer size and remote position — some 12,500 feet underwater and 400 nautical miles off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada — have made it nearly impossible for anyone to see the full picture.

Until now, that is. Using technology developed by Magellan Ltd., scientists have managed to map the Titanic in its entirety, from its bow and stern sections (which broke apart after sinking) to its 3-by-5-mile debris field.

Newly released footage of a 1986 Titanic dive reveals the ship's haunting interior

The result is an exact "digital twin" of the wreck, media partner Atlantic Productions said in a news release.

"What we've created is a highly accurate photorealistic 3D model of the wreck," 3D capture specialist Gerhard Seiffert says. "Previously footage has only allowed you to see one small area of the wreck at a time. This model will allow people to zoom out and to look at the entire thing for the first time ... This is the Titanic as no one had ever seen it before."

The Titanic site is hard to get to, hard to see and hard to describe, says Jeremy Weirich, the director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Ocean Exploration program (he's been to the site).

Pop Culture Happy Hour

'titanic' was king of the world 25 years ago for a good reason.

"Imagine you're at the bottom of the ocean, there's no light, you can't see anything, all you have is a flashlight and that beam goes out by 10 feet, that's it," he says. "It's a desert. You're moving along, you don't see anything, and suddenly there's a steel ship in front of you that's the size of a skyscraper and all you can see is the light that's illuminated by your flashlight."

This new imagery helps convey both that sense of scale and level of detail, Weirich tells NPR.

Magellan calls this the largest underwater scanning project in history: It generated an unprecedented 16 terabytes of data and more than 715,000 still images and 4k video footage.