How to Use Project Management in Education?

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed and disorganized in school? Do you wish there was a way to manage your time and assignments better?

Look no further because I have an exciting framework for you! In this blog post, we will explore the concept of project management and how it can be applied to education.

Project management skills are useful not only in the business or professional world but can also greatly benefit students in their academic journey. So whether you’re a high school student struggling with multiple classes or a college student balancing coursework and extracurriculars, this article is for you.

Get ready to learn some valuable tips and tricks on using project management skills to excel in your education!

What is Project Management?

Project management in business involves organizing, project planning, and carrying out projects to meet certain organizational goals. When applied to education, these tasks could include implementing new technology in classes, preparing for big events like graduations, or introducing new lessons.

Simply put, project management helps ensure that project planning is completed quickly, correctly, and within the allocated funds. It involves breaking down larger tasks into smaller manageable ones, setting deadlines and milestones, assigning project management roles and responsibilities, and tracking progress.

What Do Project Managers Look Like in Educational Settings?

In an educational setting, a project manager coordinates a project’s different parts and ensures they all fit with the overall educational goals. This job might include talking to stakeholders, allocating resources, and keeping track of deadlines.

Through careful planning and organization, the project manager ensures that the different needs of the students, teachers, and administrative staff are met.

How Does Effective Project Management Benefit You in Education?

Some of the most important benefits of project management in education are the following:

- Enhanced Efficiency : Through structured planning and execution, schools can maximize resource use and reduce waste.

- Better Accountability: Everyone knows what they are supposed to do when roles and tasks are clear. This makes it easier to keep track of performance and progress.

- Better Use of Resources : Knowing the requirements and scope of a job helps make better use of time, money, and materials.

- More adaptability: good project management includes planning for what could go wrong, which helps schools be ready to deal with changes or problems that come up out of the blue.

How Do You Apply Project Management Skills in Education?

Project-based learning is a common way to teach where students gain knowledge and skills by working on difficult questions, problems, or tasks for a long time. Here are some project management rules that can help make sure that student projects are successful:

Planning and Goal Setting

Picture yourself as an educator: you have exciting ideas, whether it’s a new lesson series, a field trip, or a broader curriculum change. The key to translating those ideas into reality is solid planning and setting clear goals. Here’s how a project management approach makes this happen:

- Start with the big picture: What’s the ultimate outcome you want to achieve? Get specific!

- Break it down: Instead of one overwhelming task, create a series of smaller, more manageable steps.

- Set deadlines: When must you accomplish each step to meet your overall goal?

Additionally, it’s crucial to adapt your plans based on your class’s unique needs and pacing. This flexibility allows you to adjust timelines or instructional strategies to maximize learning outcomes.

In this way, project management isn’t just about sticking to an entire project plan but also about responding to the classroom dynamics and ensuring that all students can successfully reach their educational goals.

Resource Management

Just like project managers in any field, educators need to be resourceful! This means knowing how to identify, allocate, and manage the things you need to make your projects successful. This could include physical materials, funding, time, technology, or even the knowledge and skills of those around you.

How to Manage Resources as an Educator

Risk Management

Teaching students to anticipate potential risks and devise strategies to mitigate them prepares them for unpredictable scenarios, both in and out of academic settings.

Here are key questions to guide your risk management approach in educational projects and how to approach them:

- What could go wrong? Brainstorm a comprehensive list of potential issues, from minor setbacks to major disruptions.

- How likely is each risk to occur? Rate each risk as low, medium, or high probability.

- What would the impact be if a risk became a reality? Consider how it would affect your timeline, budget, student outcomes, or overall project success.

- How can you prevent or minimize each risk? Are there proactive steps you can take to reduce the likelihood or impact?

- What’s your contingency plan? If a risk does occur, what specific actions will you take to address it?

- Who is responsible for monitoring each risk? Assign individuals or multiple team members to track potential problems and implement contingency plans.

- When will you review and update your risk assessment? Schedule regular check-ins to adjust your plan as circumstances change.

Being Resourceful and Getting Expert Help

Students undertaking complex educational projects can greatly benefit from external expertise when applying project management principles to education. Papersowl, a professional essay writing service, provides a critical resource.

This platform employs top-rated writers who contribute not only by crafting high-quality papers but also by imparting essential project management techniques that students can apply to their complex projects. Accessing online help through an essay service at critical stages of a project can decisively improve the quality of a student’s work, ensuring adherence to academic standards and project timelines.

This integration of professional support helps students manage their academic projects more effectively, thereby boosting their productivity and educational outcomes.

How to Integrate Technology in Project Management Education?

Technology is an important part of modern schooling. Software made just for schools that manage projects can help teachers and managers better plan, carry out, and monitor projects.

Students and teachers can communicate and work together better using project management tools . These tools often offer places to talk, share files, and get feedback in real-time, all of which are necessary for flexible educational projects.

Here’s a list of tools that help deliver discussions, instructions, and information:

1) Google Workspace for Education

This suite of tools, previously known as G-Suite for Education, is designed specifically for classroom collaboration. It includes essential applications such as Google Docs, Sheets, and Slides, allowing students and teachers to share files and collaborate in real-time.

Google Drive facilitates easy file storage and sharing, while Google Classroom integrates these tools to streamline the management of assignments and feedback. This platform is particularly useful for schools that need a comprehensive set of collaborative tools that are easy to use and manage.

2) Microsoft Teams

Microsoft Teams is a robust platform that integrates seamlessly with the Microsoft Office suite, including Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. It offers features like chat, video calls, and organizing classes and assignments within the platform for all project team members.

Teams are ideal for educational institutions already using Microsoft products and looking for a solution that supports communication and collaboration within the same ecosystem.

Known primarily for its video conferencing capabilities, Zoom has become an essential tool in education, especially for remote learning. It supports video calls, screen sharing, and breakout rooms, making it suitable for lectures, group discussions, and collaborative meetings.

Its ease of use and reliable performance make it a preferred choice for real-time communication in academic settings.

Canvas is a learning management system (LMS) that integrates various educational tools into a single platform. It supports assignments, grading, and discussions and includes features for file sharing and collaborative workspaces.

Educational institutions favor Canvas for its comprehensive approach to course management and its ability to facilitate both teaching and learning in a cohesive environment.

Moodle is an open-source LMS known for its flexibility and the wide range of plug-ins available. It supports online learning through features such as forums, databases, and wikis, which encourage collaborative work among students.

Moodle’s adaptability makes it a popular choice for institutions that require a customizable platform that can be tailored to specific educational needs.

Notion is an all-in-one workspace where users can write, plan, collaborate, and organize. It integrates notes, tasks, databases, and calendars into a single platform, making it an excellent AI project management tool for managing extensive notes, future projects, and collaborative tasks.

Notion’s flexibility and comprehensive features make it ideal for students and educators who require a versatile tool for individual and collaborative work.

Tracking and Evaluation

Using technology, teachers can monitor project progress and judge success based on set criteria. This constant evaluation helps improve project plans and results.

Here’s a concise overview of how technology aids in tracking and evaluating educational projects:

- Real-Time Monitoring and Feedback: Tools like Google Classroom and Trello allow teachers to track submissions and progress, offering immediate feedback to students, which can guide timely adjustments and improvements.

- Data-Driven Decisions: Learning management systems (LMS) such as Canvas and Blackboard provide analytics that help teachers understand student engagement and performance, allowing for targeted instructional changes.

- Collaborative Tools for Peer Review: Platforms like Microsoft Teams and Slack enable peer collaboration and feedback, fostering a supportive learning environment and encouraging peer-to-peer learning.

- Rubrics and Standardized Assessment: Educational technologies often include features to create and apply rubrics, helping standardize assessments and clarify expectations, which makes grading transparent and consistent.

- Adaptive Learning Technologies: Some LMS platforms adjust the difficulty of content based on individual student performance, ensuring personalized learning experiences that are challenging yet accessible.

- Portfolio and Progress Tracking: Digital portfolios, supported by platforms like Notion, help students and teachers track long-term progress and reflect on learning outcomes over time.

- Automated Testing and Quizzes: Automated assessments within LMS platforms provide quick insights into student understanding, offering immediate feedback and helping teachers identify areas that need further instruction.

These technological tools streamline the process of project tracking and evaluation, enhancing educational outcomes through structured support and comprehensive data analysis.

Challenges of Implementing Project Management in Education

There are clear benefits to applying project management skills in school , but it’s not always easy.

First, there is a lack of awareness and training among students and educators. Many students are not aware of project management techniques and their importance in academic work, which can lead to disorganized and inefficient project completion.

Additionally, there may be resistance from educators who are accustomed to traditional project management methodologies in a school setting and may not see the value in incorporating project management into their curriculum.

Another challenge is the limited resources available for students to access professional support. While essay services can provide valuable assistance, not all students have access to them or may not be able to afford them.

However, despite these challenges, it’s important for educators to recognize the benefits of project management and strive to incorporate it into their teaching and project management methods.

Final Thoughts on Project Management

Project management in education offers a structured approach to managing educational projects, enhancing learning outcomes, and preparing students for future challenges. By adopting project management principles, educational institutions can operate more efficiently and responsively, fostering an environment where administrative goals and educational strategies align seamlessly.

Embracing these practices, educators, and administrators can ensure that they are not just teaching students but also providing them with a framework for success in their academic and professional futures.

Dev is a strategist, productivity junkie, and the founder of the Process Hacker !

I will help you scale and profit by streamlining and optimizing your operations and project management through simple, proven, and practical tools.

To get help for your business, check out my blog or book a call here !

Similar Posts

SWOT Analysis: Establish Strategy for Success

The SWOT Analysis is a strategic technique to guide corporate decision making at the highest level or for specific objectives. The acronym stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

What is a Fractional CMO? Why Hire One?

Boost marketing with a Fractional CMO, replacing full-time execs. Expertise drives growth, transforms approach, and achieves goals!

Notion vs ClickUp: Which Project Management Tool is Better?

Deciding between Notion or ClickUp for your business’s main project management tool? In this post, we will break down Notion vs ClickUp!

The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy | Summary

In his book, The Compound Effect, Darren Hardy shows you how to harness the power of The Compound Effect to create the success and the extraordinary life you want.

The 8 Best AI Note-Taking Apps In 2024

AI note-taking apps are making it much easier and more fun to take notes, so check out our top picks to be more productive in note-taking!

Clockify vs Toggl: Which Time Tracking Tool is Better?

Clockify vs Toggl: Both are incredible time-tracking tools for freelancers, small businesses, and remote workers, so learn more about them!

Advertisement

Teaching project management to primary school children: a scoping review

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sante Delle-Vergini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9762-0326 1 ,

- Douglas Eacersall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2674-1240 2 ,

- Chris Dann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7477-0305 3 ,

- Mustafa Ally ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6370-3860 4 &

- Subrata Chakraborty ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0102-5424 5 , 6

1862 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This article has been updated

Teachers have used projects in children’s education for over a century. More recently, project management knowledge and skills have become essential when students manage technological solutions from inception to presentation. This paper presents the first scoping literature review on teaching project management to primary school students. A total of 33 publications between 2000 and 2022 were analysed and presented both descriptively and thematically. While the review did not identify any empirical studies of teaching project management to primary school students, it did reveal several examples of suggested teaching approaches, project management activity, and common elements associated with project management. The review concludes with a recommendation for researchers, educators, and project management practitioners to build upon this research by exploring the effectiveness of comprehensive approaches to teaching project management to primary school students. This paper represents a significant area of research as project management is one of the most critical skills for students to achieve success in the twenty-first century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Project Management Office and Teaching and Learning Center: A Comparative Literature Review

The key characteristics of project-based learning: how teachers implement projects in K-12 science education

Anette Markula & Maija Aksela

Effective Learning Through Project-Based Learning: Collaboration, Community, Design, and Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Using projects in children’s education dates back to the early twentieth century (Knoll, 2012 ; Pomelov, 2021 ) and was popularised by William Kilpatrick (Clark, 2006 ), one of the most influential figures in pedagogical progressivism (Mintz, 2016 ). Since then, teachers have increasingly used real-world projects to provide authentic learning experiences for their students (Pecore, 2015 ). More recently, teachers and researchers have begun to examine the pedagogies that surround projects that help teachers deliver multiple curriculum outcomes in a single learning activity. Given the prevalence of projects and the emphasis on curriculum outcomes, it is understandable that teachers may have less focus on the processes and skills involved in managing these projects. At the same time, as students take on more responsibility for their own projects, there will be a growing need to develop project management skills.

Project management can be defined as ‘the knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements’ (Project Management Institute [PMI], 2021 , p. 245). It is a complex discipline that has evolved over several decades through leading institutions such as the Project Management Institute, the Association for Project Management, and the International Project Management Association. Like other disciplines, the field of project management has created a body of knowledge that is transferable to practice (Lalonde et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, as organisations continue to use projects as the primary form of structuring work, most employees will be involved in project-related activities of some kind in the workplace (Konstantinou, 2015 ). Of these, approximately 90 million individuals will be performing project management activities by 2027 (PMI, 2017c ). As a result, many of these individuals will require education and training in project management.

Institutions such as PMI have developed methodologies, practices and standards that underpin many of the project management education and training programs available today (Cicmil & Gaggiotti, 2018 ). Some programs include short courses, degree programs, industry training, professional development, and the ‘global standard’ in project management certifications: the Project Management Professional (PMP) accreditation from PMI (Richardson & Jackson, 2019 , p. 26). While the complexity of these programs varies greatly, the concepts and terminologies are generally targeted at the adult population, not children. Nevertheless, there is some evidence of project management teaching in secondary schools and youth non-profit organisations. In 2018, the Student Research Foundation (SRF) surveyed over 35,000 secondary school students across the United States and found that 25% of students reported that they had been taught project management skills (SRF, 2019 ). In the United States, two examples of initiatives to teach project management skills in secondary school include a pilot in a Washington State high school where students in Grades 9 to 12 were taught project management over one semester (Garfein & Noeldner, 2011 ), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) commissioning Texas A&M University to design and implement a project management course to assist students in six high schools to better manage their Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) projects (Morgan et al., 2013 ). In Hampshire, England, a secondary school became the first in the United Kingdom to implement a pilot program by the Project Management Institute Educational Foundation (PMIEF) to introduce project management principles to students (Robertson, 2012 ). Finally, JA (Junior Achievement) Europe, a large youth-serving non-profit organisation that prepares students for the workforce, received a grant totalling USD $977 K from PMIEF to integrate project management learning into their youth programs (PMIEF, 2021 ). Although these examples of project management learning in secondary schools are encouraging, primary school children should also learn how to manage projects as a life and career skill (Partnership for 21st Century Learning [P21], 2019 , p. 7).

In Australia, young children are already exposed to projects and project management. In 2012, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) produced The Shape of the Australian Curriculum: Technologies (ACARA, 2012 ). The Technologies curriculum was designed to ensure that students capitalise on the learning and application of emerging technologies critical to twenty-first century living. An overarching theme within the curriculum is the potential students have to influence their future through developing technological solutions (ACARA, 2012 ). Project management learning in primary school classrooms is a key concept within the Australian Technologies curriculum, made evident by the title of ACARA’s Digital Technologies in Focus (DTiF) publication: Teaching and supporting project management in the classroom F-6 (DTiF, 2020 ). The curriculum claims that students will produce technological solutions by managing projects from inception to realisation and can be measured by comparing how successfully a project met original expectations (ACARA, 2012 ). ACARA believes that project management is ‘an essential element in building students’ capacity to more successfully innovate’ and will be included in every year of schooling (ACARA, 2012 , p. 10). This implies that teachers will develop opportunities for students to understand how to manage a project.

Despite ACARA’s recommendation that project management should be explicitly taught within the Technologies curriculum (DTiF, 2020 ), a preliminary search of the literature, both nationally and internationally, found no comprehensive research studies on teaching project management in a primary school context. There was some evidence of project management activity identified through various pedagogical practices such as inquiry-based learning, problem-based learning, differentiated instruction, and particularly project-based learning. These included common project management activities such as planning, group work, producing a product, and presenting to an audience. However, these activities alone do not constitute a holistic view of the knowledge and skills required for a child to successfully manage a project from beginning to end. Project management integrates numerous elements that must be managed effectively (PMI, 2017a ) by an individual with a set of core competencies (PMI, 2017b ). This is made more complex by the various ages of children in primary school.

This raises some significant questions. If project management is such a complex discipline, how is it being taught to primary school children? What research has been conducted investigating comprehensive approaches to the teaching of project management to children in primary school? To explore these questions further, and to inform the Australian situation, an international scoping review was undertaken to: (i) investigate the body of literature regarding teaching project management in primary schools; (ii) identify approaches to the teaching of project management and related skills in the classroom; and, (iii) build a foundation of evidence to inform future research. This paper is the first scoping literature review investigating the teaching of project management to primary school children.

A scoping review methodology was selected to explore the literature as this type of review aims to examine the extent, range and nature of research on a particular topic, summarise and disseminate the findings, and identify any research gaps in the literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ). Due to the sparseness of literature on the topic, the research was driven by a broad research inquiry resulting in the following research question: What does the body of evidence reveal about teaching project management to children in primary school? The use of a scoping review provides more flexibility than a systematic review (Peterson et al., 2017 ) because it is more concerned with the characteristics and concepts within a study than a specific question that informs policy or practice (Munn et al., 2018 ). Further, the results should only focus on a descriptive account of available literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ).

Scoping reviews often present information in broad themes (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Rumrill et al., 2010 ). Two themes emerged from the initial search of the literature: project management elements, and teaching project management to primary school children. Project management elements describe the project management activities, processes, and artefacts typical of many projects. This was the predominant theme due to the sheer volume of project management elements identified in the initial search. Teaching project management to primary school children is the central topic of this research. This theme concerns specific claims that project management is or should be taught in primary schools.

This scoping review adheres to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020 ) and is guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., 2018a ). Lockwood et al. ( 2019 ) recommend the use of both resources when developing a scoping review. Further, a scoping review protocol was previously published by the authors of this paper (Delle-Vergini et al., 2023 ) to promote transparency and detail the objectives and methods of this review (Peters et al., 2020 ).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were based on the PCC (population, concept, context) mnemonic, using the following phrases: children (population), teaching project management (concept), and primary school (context), which were also used to develop the scoping review article title and research question (Peters et al., 2020 ). Using the PCC mnemonic ensures a broader range of sources are considered compared to the population, intervention, comparator, outcome (PICO) mnemonic commonly used in systematic reviews (Lockwood et al., 2019 ). The population included studies that involved primary school students, regardless of gender or socio-economic status. The concept of this scoping review is teaching project management, while the context includes any public or private primary school that teaches or claims to teach project management to children or where children are engaged in project-related activities that produce products and project management artefacts. As the age of primary school students can vary across countries and even between states, a range of 5–11 years of age was used during the screening process as this range is almost exclusively situated in a primary school setting. Information sources considered include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies and reports. Journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, published books and grey literature from the years 2000 to 2022 were included to ensure the literature was relevant in twenty-first century classrooms. The validity of sources was achieved through the credibility of the institutions they were sourced from (i.e., Project Management Institute) and the academic databases mentioned in the next section.

Search strategy and source selection

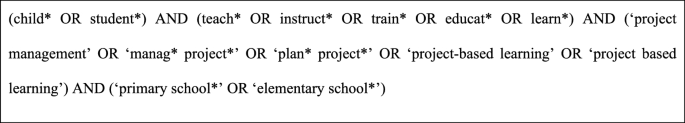

As recommended by Morris et al. ( 2016 ), the search design and strategy involved a research librarian. Consistent with the JBI methodology, it involved three stages (Peters et al., 2020 ). During the first stage, an initial search of the following databases: Academic Search Ultimate, Business Source Ultimate, eBook Collection, Education Research Complete, E-Journals, ERIC (all via EBSCOhost Megafile Ultimate), Proquest One Academic, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar was conducted independently by two of the authors (SD, DE). The use of at least two reviewers to meet, discuss and select relevant sources is recommended by Levac et al. ( 2010 ). The search utilised synonyms and like terms derived from phrases located in the title of this paper, as detailed in Fig. 1 . This search yielded 799 results.

Search string

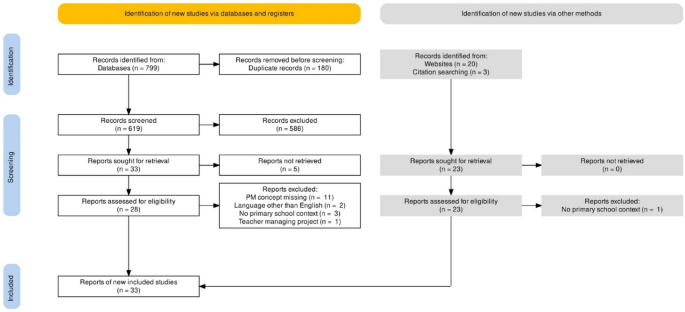

The sources were then loaded into EndNote, and duplicates removed, yielding a total of 619 sources. On several occasions, the same two authors (SD, DE) met to discuss and agree on the items for inclusion and exclusion. A title and abstract examination of the 619 sources resulted in 586 exclusions, leaving a total of 33 sources for consideration. A full-text examination of these 33 sources commenced, resulting in 22 excludes (full text not found: n = 5, project management concept missing: n = 11, a language other than English: n = 2, no primary school context: n = 3, only teacher managing project: n = 1), leaving a total of 11 included sources.

In the second stage, a manual search for other sources (i.e., websites) was performed. This process was necessary as the search of databases only produced limited sources. A handful of websites (i.e., Project Management Institute Educational Foundation, Buck Institute for Education) produced content in the form of reports, videos, blogs, and recommendations for books that referenced project management teaching in primary schools. The process of searching these and other websites and their content produced a further 20 sources, one of which was excluded after closer examination. The third and final stage examined the reference lists of the 11 database sources and 19 website sources which produced a further three sources.

This rigorous search strategy and source selection process produced a total of 33 sources that matched the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. The process is detailed in Fig. 2 .

Scoping review search and selection process

Data extraction and presentation

Despite the growing use of the JBI methodology and PRISMA-ScR checklist, a study by Khalil et al. ( 2020 ) discovered that of all the stages throughout the scoping review process, data extraction was the most inadequate. Data extraction was made difficult by the lack of explicit examples of approaches to teaching project management in primary schools. As such, it was necessary to identify and group project management elements to capture and understand the characteristics of the teaching of project management within the literature. The authors decided that the phases within a project life cycle were a logical choice to group the project management elements.

A project life cycle consists of phases of related project activity that a project passes through until it is completed (PMI, 2017a ). While there is no universal agreement on project life cycle phases (Kerzner, 2022 ), the authors selected four project management process groups: initiate , plan , execute , and close , which reflect the four generic project life cycle phases: starting the project, organising and preparing, carrying out the work, and ending the project (PMI, 2017a ). Each phase contains several project management elements that were used to map the results in tabular format (Thomas et al., 2017 ). The elements extracted were important in identifying the building blocks of project management and were largely derived from two key Project Management Institute publications: A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge: PMBOK® Guide (PMI, 2017a ), widely considered as ‘the gospel of project management’ (Kerzner, 2010 , p. 169), and the Project Manager Competency Development Framework (PMI, 2017b ). Seventeen project management elements across four project lifecycle phases were used to capture evidence of project management activity.

A comprehensive mapping of the 33 sources included in this scoping review and the project management elements identified in each source are provided in Table 1 of the Appendix and should be referred to throughout this paper. This section includes a descriptive overview of the results, followed by a thematic overview, as recommended by Levac et al. ( 2010 ). To supplement the numerical analysis in this paper, such as number counts and percentages, the authors used the following classification schemes: ≤ 33% was interpreted as a low level of representation; 34–66% as a moderate level; and ≥ 67% as a high level.

Descriptive overview

Due to the limited number of research articles discovered, the data extraction elements typical of a scoping review, such as study aims, population sample, methodology and key findings (Peters et al., 2020 ), were not available for most sources and thus were excluded from this scoping review.

Publication source The scoping review sources consisted of a thesis ( n = 1), published books ( n = 6), journal articles ( n = 7), web documents ( n = 7), government documents ( n = 2), conference proceedings ( n = 1), videos ( n = 3), and blogs ( n = 6). Of the seven journal articles, one could not be confirmed as peer-reviewed (D’Orio, 2009 ).

Year of publication The inclusion criteria prohibited sources published earlier than the year 2000. In chronological order, sources were published in the year 2000 ( n = 2), 2002 ( n = 1), 2005 ( n = 1), 2008 ( n = 1), 2009 ( n = 2), 2010 ( n = 1), 2012 ( n = 1), 2013 ( n = 1), 2014 ( n = 4), 2015 ( n = 3), 2016 ( n = 3), 2017 ( n = 3), 2018 ( n = 6), 2019 ( n = 1), 2020 ( n = 2), and 2022 ( n = 1). It is uncertain exactly when ACARA ( 2022 ) was published, as there are multiple versions, but version 8.4 of the Australian Technologies curriculum (Foundation to Year 6) is the latest version as of writing this article.

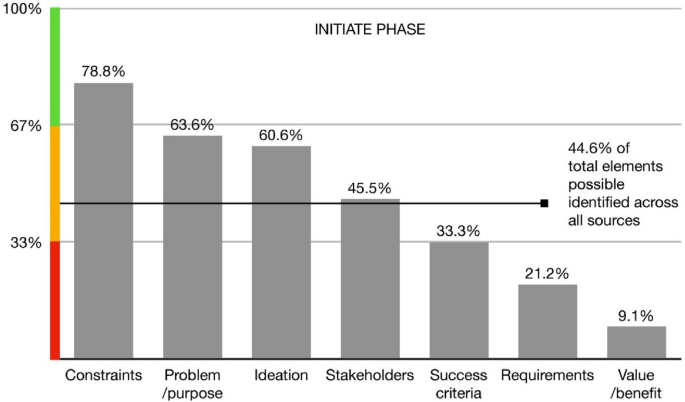

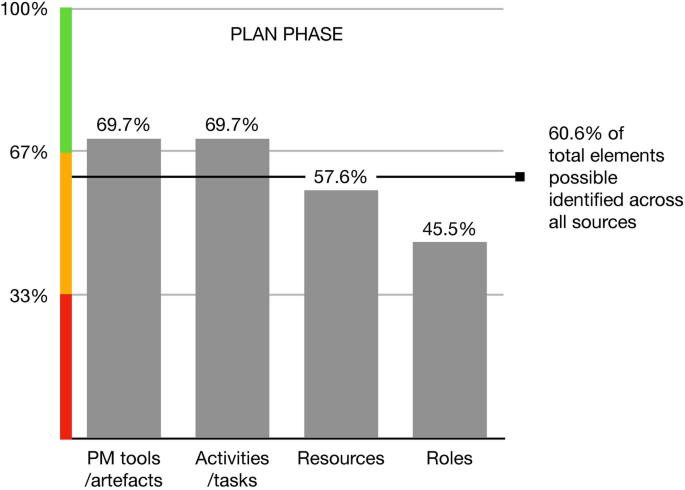

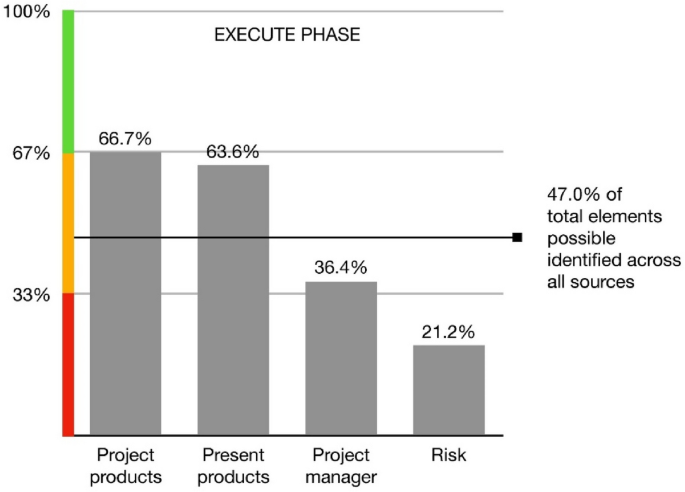

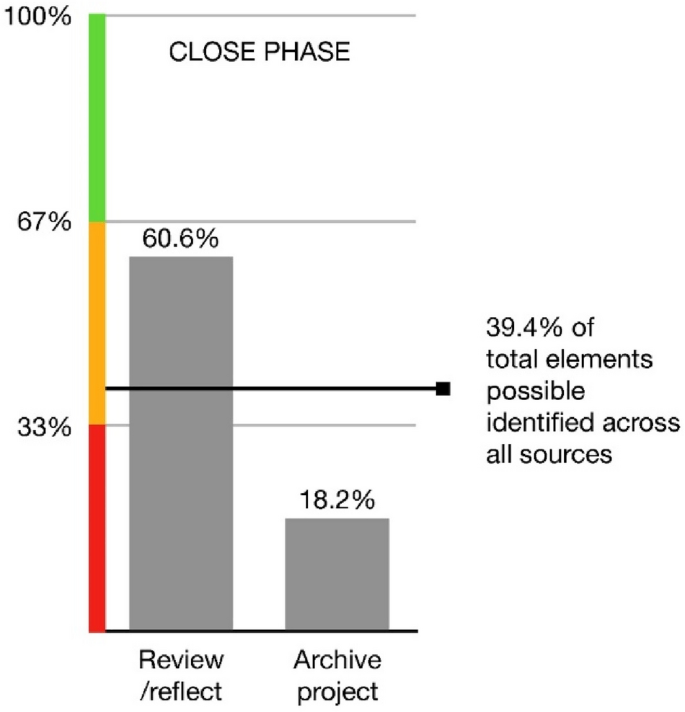

Project management elements by phase Only 19 (57.6%) sources contained at least one element in each of the four phases (initiate, plan, execute, close). The initiation phase contained 103 of 231 (44.6%) possible elements identified across 33 sources. The planning phase contained 80 of 132 (60.6%) possible elements. The execution phase contained 62 of 132 (47.0%) possible elements. Finally, the closing phase contained 26 of 66 (39.4%) possible elements. Of the 561 project management elements possible across all sources and phases, only 271 (48.3%) were present.

Project management elements by publication type and source Of the 17 project management elements available, government documents (30 of 34; 88.2%), web documents (107 of 153; 69.9%) and books (71 of 102; 69.6%) contained a high level, followed by a moderate level for theses (10 of 17; 58.8%), and journal articles (54 of 119; 45.4%), and a low level for videos (12 of 51; 23.5%), conference proceedings (4 of 17; 23.5%) and blogs (13 of 102; 12.7%). Nine sources (27.3%) contained a high level of elements (12 elements and above), 13 sources (39.4%) contained a moderate level (6–11 elements), and 11 sources (33.3%) contained a low level (5 elements and below). Only three elements were identified in a high number of sources: constraints ( n = 26; 78.8%), and both project management tools/artefacts ( n = 23; 69.7%) and activities/tasks ( n = 23; 69.7%).

Thematic alignment The two themes presented in this paper were identified in a number of sources. Project management elements ( n = 30; 90.9%), and teaching project management to primary school children ( n = 14; 42.4%).

Thematic overview

Two themes emerged from the review of the literature: project management elements, and teaching project management to primary school children. Each theme is briefly described in the Methods section.

Project management elements

Seventeen elements provided evidence of project management activity within the literature, the people and processes involved, the artefacts used in managing projects, and the products produced during those projects. These elements were categorised into four groups representing common phases within a project lifecycle: initiate, plan, execute, and close.

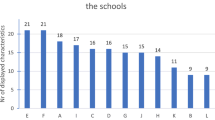

Initiate Phase This phase only contained 103 of 231 (44.6%) possible elements across all sources. Only one source contained all seven elements (PMIEF, 2014a ). ACARA ( 2022 ), DTiF ( 2020 ), and Fleer ( 2016 ) each contained six elements; while Boss and Larmer ( 2018 ), Edwards ( 2000 ), Ginevri and Trilling ( 2017 ), PMIEF ( 2015a ), Project Management Institute: Portugal (PMI-Portugal, 2020 ), and Railsback ( 2002 ) all contained five elements. Four sources (Lenz, 2016 ; Modzelewski & Urias, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014b; Vander Ark, 2018 ) contained no elements. The percentage of sources where each element was identified is illustrated in Fig. 3 .

Project management elements of the initiate phase identified in sources

The most predominant element identified within this phase was constraints ( n = 26; 78.8%). Constraints within a project typically include time, scope, and cost (PMIEF, 2015a) and should be considered to see how they might affect the project (Portz, 2014 ). Time was the leading constraint and described in several ways, such as managing time or time management (Buck Institute for Education [BIE], 2018 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; Lenz, 2018 ; Trilling & Fadel, 2009 ), keeping on track (Bell, 2010 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ; Railsback, 2002 ), deadlines (DTiF, 2020 ; Krajcovicova & Capay, 2012 ; McCain, 2005 ; PMIEF, 2015a ), timelines (ACARA, 2022 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Edwards, 2000 ; Railsback, 2002 ), and schedules (DTiF, 2020 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ). Time management was the number one difficulty faced by students in projects according to Akinoglu ( 2008 ). Scope (Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a ), cost or budget (ACARA, 2022 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ), and quality (ACARA, 2022 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ) were mentioned less frequently than time constraints.

The next two prominent elements identified were problem/purpose ( n = 21; 63.6%) and ideation ( n = 20; 60.6%). Most projects in a school environment begin with a purpose (DTiF, 2020 ; Folsom, 2000 ; Railsback, 2002 ), question (Bell, 2010 ; BIE, 2018 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ; Trilling & Fadel, 2009 ), or problem that needs to be solved (Akinoglu, 2008 ; Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Fleer, 2016 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; Reitzig, 2019 ). Ideation occurs when students ‘explore, analyse and develop ideas’ (ACARA, 2022 , p. 6) and illustrate these ideas (Maher & Yoo, 2017 ) through activities such as brainstorming (Project Management Institute: North Italy Chapter [PMI-NIC], 2015 ; PMIEF, 2013 , 2015b ; Portz, 2014 ) and mind mapping (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a ).

Like problem/purpose and ideation, the stakeholder element had a moderate level of representation ( n = 15; 45.5%). A stakeholder is an individual or group interested in the project (PMIEF, 2015b ). DTiF ( 2020 ) recognised the importance of reporting to, and receiving feedback from, stakeholders. In the context of a primary school project, sources that mentioned stakeholders often referred to them as teachers, parents, or community members (Bell, 2010 ; Edwards, 2000 ; French, 2018 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ; Railsback, 2002 ). Some sources referred to a stakeholder as a client (Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2014a ). One source even described a stakeholder analysis process: ‘The students also filled out a stakeholders table that identified each person with a key interest in the project, their role, what they wanted from the project team, and how the team planned on giving them what they needed’ (PMIEF, 2014a , p. 17).

The final three elements: success criteria, requirements, and value/benefit, had a low representation across the sources. Although the success criteria element was the best of the three ( n = 11; 33.3%), requirements ( n = 7; 21.2%) and value/benefit ( n = 3; 9.1%) were significantly lower.

Plan phase This phase had the highest representation of project management elements compared to other phases, with 80 of 132 (60.6%) possible elements identified, making it the only phase to score above 50%. Twelve sources (ACARA, 2022 ; Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Edwards, 2000 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; Krajcovicova & Capay, 2012 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ; Portz, 2014 ) included all four project management elements (tools/artefacts, activities/tasks, resources, and roles) in this phase. There were no elements with a low level of representation across all sources, as detailed in Fig. 4 .

Project management elements of the plan phase identified in sources

Project management tools/artefacts and activities/tasks were two elements that had a high level of representation across sources ( n = 23; 69.7%). Project management tools/artefacts are any items that assist project team members in conducting project management activities. While the list of items can be extensive depending on the size and complexity of the project, several sources cited what is arguably the most important document or artefact in every project: the project plan (ACARA, 2022 ; Akinoglu, 2008 ; Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ), or master plan (Edwards, 2000 ). Other project management tools and artefacts identified were task boards, project walls, project journals (Boss & Krauss, 2014 ), Gantt charts, contingency plans, risk registers, work breakdown structure, communication plan (DTiF, 2020 ), visual maps, project binders, resource plans, project goal statement (Edwards, 2000 ), posters, mind maps, process diaries (Fleer, 2016 ), activity tree, project traffic light (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015b ), project organisation chart (PMIEF, 2014a ), project scoring rubric and task lists (Portz, 2014 ).

Activities/tasks were used interchangeably by several sources (BIE, 2018 ; Edwards, 2000 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; Larskikh et al., 2016 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ). The purpose of this element is to define all the necessary activities or tasks to complete the project (PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; Portz, 2014 ). Edwards ( 2000 , p. 63) calls on students to ‘think through the activities they must complete to meet their project goal…compose a master list of activities…which need to be broken out into smaller tasks’. The concept of an Activity Tree (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015b ) provides a graphical representation of the tasks necessary to complete the project. Each leaf on the tree represents an activity or task. These tasks are then assigned deadlines and owners (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ) with a ‘logical sequence of steps they (students) intend to follow to accomplish the tasks’ (McCain, 2005 , p. 59).

Both resources ( n = 19; 57.6%) and roles ( n = 15; 45.5%) were moderately represented. Project resources include people (Edwards, 2000 ; Fleer, 2016 ); equipment, tools, materials, funding, technology, books (PMIEF, 2015a ), whiteboards, cameras, USB drives, computers, printers, scanners, data projector, internet (Krajcovicova & Capay, 2012 ), components (ACARA, 2022 ), and supplies (Folsom, 2000 ). Students are encouraged to consider why resources are necessary and how they will be managed for each activity (Nodzynska et al., 2018 ).

During a project, students ‘negotiate roles and responsibilities’ (ACARA, 2022 , p. 57), with roles defined for both individuals and groups (DTiF, 2020 ). School projects leverage the abilities and strengths of individual team members when assigning roles (Fleer, 2016 ; Reitzig, 2019 ) and provide opportunities for students to take on leadership roles (Trilling & Fadel, 2009 ). Some sources also recognised the dual nature of roles and responsibilities in project work (ACARA, 2022 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Railsback, 2002 ).

Execute Phase The execute phase contained 62 of 132 (47.0%) possible elements across all sources. Students spend most of their time during the execution phase of the project (PMIEF, 2014a ). Only three sources (DTiF, 2020 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ) included all four elements (project manager, project products, present products, and risk) in this phase. None of the elements had a high representation across sources, as detailed in Fig. 5 .

Project management elements of the execute phase identified in sources

Project management elements of the close phase identified in sources

The first two elements identified within the execution phase are project products and present products . Two-thirds of the sources ( n = 22; 66.7%) demonstrated that a product of some kind was the end result of projects undertaken in the primary school classroom. Other terms that reflected a product included scale model (Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; French, 2018 ), prototype (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2015a ), solution (ACARA, 2022 ; PMIEF, 2015a ; Reitzig, 2019 ), service (PMIEF, 2015a ), and design (Reitzig, 2019 ). In every source where a project product was identified, it was a tangible product. As Railsback ( 2002 , p. 10) points out, a tangible product is an important feature of authentic classroom projects and should be shared with an intended audience. The presentation of project products was evident in many sources ( n = 21; 63.6). Whether it was a presentation (BIE, 2018 ; Edwards, 2000 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Folsom, 2000 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ; Railsback, 2002 ), contest/competition (Akinoglu, 2008 ; Reitzig, 2019 ), performance (Bell, 2010 ), showcase (Reitzig, 2019 ), exhibition or portfolio (Maher & Yoo, 2017 ), a final product of some kind was presented to interested stakeholders.

The project manager is responsible for ensuring that the project meets its goals (PMIEF, 2014a , p. 41). However, this element was only moderately represented ( n = 12; 36.4%). ACARA ( 2022 , p. 52) states that ‘students manage projects independently and collaboratively from conception to realisation’. Two sources (Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; Larskikh et al., 2016 ) specifically refer to students as project managers, while one (DTiF, 2020 ) refers to students managing their own projects. However, some sources appear to suggest that students should manage projects independently once they enter secondary school. Fleer ( 2016 , p. 233) argues that students can manage their projects but should build upon the concepts of project management in primary school and then become more independent in secondary school. This gradual progression to independently managing projects is supported by Ginevri and Trilling ( 2017 , p. 51): ‘As project learning experiences grow, so does the need for students to take more control of the entire project management processes.’ Other sources discussed student involvement in the process of managing projects without specifically referring to them as a project manager or managing their own individual projects (BIE, 2018 ; Folsom, 2000 ; Lenz, 2016 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ). A handful of sources ( n = 4) referred to teachers playing the role of a project manager (Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Folsom, 2000 ) in addition to students.

The final element is risk . This element was identified in a low number of sources ( n = 7; 21.2%). Some sources understood the importance of identifying and managing risks in the project management process. The project team should identify risks (PMI-Portugal, 2020 ), create a list of risks (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ) or risk register (DTiF, 2020 ), manage the risks (ACARA, 2022 ), and consider creating a risk management or backup plan (Fleer, 2016 ).

Close Phase This phase contained 26 of 66 (39.4%) possible elements across all sources. This scoping review searched for two elements in the closing phase: review/reflect and archive project . Given the temporary nature of projects, they must eventually be closed. One of the final activities for a project team is to discuss and document the lessons learned (PMIEF, 2015b ). Five sources (Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Edwards, 2000 ; PMIEF, 2014a ) included both elements, while 12 sources did not refer to either element (Fig. 6 ).

A moderate level of sources ( n = 20; 60.6%) included or recommended a review/reflect process. The project review process involves feedback from stakeholders, celebrating project success, informal and formal recognition, and self-reflection, which ‘may hold the most important learning experiences in the whole project’ (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 , p. 53). The quality of the project results can be analysed (Larskikh et al., 2016 ), lessons learned reviewed (PMIEF, 2015a ), and project processes improved (Boss & Krauss, 2014 ). Further, reflecting on how successful the project was in meeting the client’s needs (ACARA, 2022 ) and suggestions for improvement can make the next project even better (Edwards, 2000 , p. 82). The Buck Institute for Education suggests that the review and reflection process will assist students to ‘retain project content and skills longer, develop a greater sense of control over their own education, and build confidence in themselves’ (BIE, 2018 , p. 5). As such, the entire review process can often be applied to future projects (Trilling & Fadel, 2009 ).

The archive project element, where project artefacts or products are stored away for future use or showcasing, was one of the lowest performing of all 17 elements ( n = 6; 18.2%). While several sources throughout the review/reflect process produced material that could be archived, only six sources were clear about the need to document project success/failure, performance, and lessons learned for future use (Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; D’Orio, 2009 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Edwards, 2000 ; PMIEF, 2014a ). These archives can be used to discuss previous projects (DTiF, 2020 ), review artefacts, and recall certain challenges (Boss & Larmer, 2018 ) that can inform future projects.

Teaching project management to primary school children

Despite a wide range of project management elements and activities identified in this review, no empirical studies of comprehensive approaches to teaching project management to primary school children were identified. A moderate level of sources ( n = 14; 42.4%) described or promoted project management teaching in the classroom. Four sources (DTiF, 2020 ; Fleer, 2016 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMIEF, 2015b ) clearly identified project management teaching in a primary school setting, although DTiF ( 2020 ) and Fleer ( 2016 ) briefly referred to a secondary school setting. Some sources discussed project management concepts that should be taught in the classroom (ACARA, 2022 ; Boss & Krauss, 2014 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ), while others provided evidence through photographs, project artefacts, or descriptions of actual project management activity (DTiF, 2020 ; Fleer, 2016 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2013 , 2014a , 2015b ). The only source with a clear definition of project management was ACARA ( 2022 , p. 40), defining it as ‘a responsibility for planning, organising, controlling resources, monitoring timelines and activities, and completing a project to achieve a goal that meets identified criteria for judging success’.

Two government sources (ACARA, 2022 ; DTiF, 2020 ) recognised the importance of scaffolding techniques to transition primary school students through increasingly complex project management concepts. The Australian Technologies curriculum is written in bands of year levels for primary school: Foundation to Year 2; Years 3 and 4; and Years 5 and 6 (ACARA, 2022 ). In Foundation to Year 2, and with teacher guidance, students plan simple steps to complete projects. In Years 3 and 4, students begin to clarify their ideas, manage their time, plan and sequence major steps, and identify project success criteria. In Years 5 and 6, students develop project plans, consider project resources, define roles, set milestones, and reflect on the success of their project product and how improvements in the project process can be made next time. This approach transitions project management learning from basic planning steps through to more complex activities such as analysing cost, time, scope, and quality constraints (ACARA, 2022 ). DTiF ( 2020 ) also suggested the use of templates and checklists that students can adapt to their own projects, with the teacher providing connections between theoretical principles and practical application of project management concepts. Scaffolding strategies like these may be necessary as some concepts, such as Gantt charts and Work Breakdown Structures, mentioned by multiple sources in the review, are too complicated for primary school children to understand (Nodzynska et al., 2018 ).

Several sources described various phases of a project lifecycle: Initiation, Planning, Execution, and Closing (PMI-Portugal, 2020); Creation, Planning, Execution/Control, and Closing (PMI-NIC, 2015; PMIEF, 2015b); Define, Plan, Do, and Review (PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ). DTiF ( 2020 ) listed Planning, Scheduling, Monitoring/Controlling, and Closing but did not include an initiation phase, although they listed several steps under planning that would normally belong to an initiation phase, such as defining the problem or need, determining the project objectives, and identifying who is involved in the project (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ).

Six sources (DTiF, 2020 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2015a , 2015b ) were prescriptive in their recommendations for teaching project management in primary schools, detailing numerous activities undertaken and artefacts produced throughout each phase of the project. In the initiation phase, these sources recognised that a key activity was to identify a problem or need and define the project objective. Other activities included generating ideas (PMIEF, 2015b ), brainstorming (PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2015a , 2015b ), the identification of stakeholders, determining the resources needed, project success criteria, project team, and deadlines (DTiF, 2020 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2015a ). Project management artefacts produced during this phase included resource lists (DTiF, 2020 ), project identity cards, mind maps (PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2015b ), project definition document, and a teamwork agreement document (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2015a ).

In the planning phase, the same six sources included defining activities or tasks, roles and responsibilities, sequencing tasks, and assigning people to tasks. PMI-Portugal ( 2020 ) highlighted the importance of defining dependencies between tasks. Artefacts produced during this phase included activity trees, project calendars (PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2015b ), work plans and checklists (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2015a ), and a work breakdown structure (DTiF, 2020 ).

In the execution phase, monitoring the project progress and adjusting the plan were activities mentioned in all six sources. Reporting project progress was also important (DTiF, 2020 ), as was checking to see if the product met original expectations (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ). Project management artefacts identified in this phase included project traffic lights (PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015b ) and meeting notes (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMIEF, 2015a ). Project traffic lights are used to gauge how project activities are progressing. Green signifies that the activity is progressing as expected; amber means that an activity could be delayed, and the project team should work to avoid the delay; and red means the activity is delayed and a solution should be implemented, such as adding resources, shortening the duration of activities, or simply accepting the delay (PMI-Portugal, 2020 ).

Finally, in the closing phase, all six sources agreed that capturing lessons learned was a key activity, while reviewing the project against success criteria (DTiF, 2020 ), discussing improvements in the project process (Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMIEF, 2015a ), and celebrating project success (DTiF, 2020 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ) were also important. Boss and Krauss ( 2014 ) even included an assessment rubric that includes project management elements such as developing project plans, managing time, meeting milestones, and project reflection. A few sources described or showed evidence of a project wall that displayed common project management artefacts such as activity lists, project calendars, mind maps and a project identity card (PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a ). This allowed teachers and students to visualise the project as a whole and keep track of project progress.

This scoping review identified the range of existing literature on teaching project management to primary school children. The review identified 33 sources containing data that met the pre-defined inclusion criteria. A distinction between this review and other scoping reviews in Education journals was the low number of journal articles ( n = 7) and high number of other sources ( n = 26), such as books, web documents, and blogs.

Several gaps in the literature were observed. Firstly, the review did not identify any empirical studies into the teaching of project management to primary school students, although it did reveal several examples of suggested approaches to teaching project management. For example, several sources described four main phases within the project lifecycle and the project management activities, processes, and artefacts produced within each phase (DTiF, 2020 ; Ginevri & Trilling, 2017 ; PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMI-Portugal, 2020 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a , 2015b ). Students need to plan, organise, control and monitor these activities and artefacts over the entire project lifecycle in order to achieve project success (ACARA, 2022 ). Further, scaffolded learning in a project environment was suggested by several sources (Bell, 2010 ; Boss & Larmer, 2018 ; DTiF, 2020 ; Maher & Yoo, 2017 ; Vander Ark, 2018 ) and, more specifically, as a way to introduce project management skills with increasing complexity at each year level (ACARA, 2022 ). Therefore, students are already engaged in the building blocks of project management. However, the lack of research studies highlights the need for more empirical investigation in this area. Qualitative and quantitative studies are required to examine the teaching of project management in primary schools, and the effectiveness of holistic approaches that seek to integrate the project management skills required for students to successfully manage a project from beginning to end in contrast to approaches that focus on these skills in isolation. This would enable a fuller understanding and informed approach to the development of such skills within the Australian Technologies curriculum.

Secondly, while the Technologies curriculum promotes the explicit teaching of project management in primary schools (DTiF, 2020 ), there is no empirical research into teachers’ perspectives on how this should be achieved. Teachers’ understanding of project management, and their views on how, when, and what exactly should be taught, impacts student learning. The review revealed some teacher experiences (Modzelewski & Urias, 2017 ) of using project management teaching resources promoted by PMIEF (PMI-NIC, 2015 ; PMIEF, 2014a , 2015a , 2015b ), but these were anecdotal and not published in peer-reviewed journals.

Thirdly, project management is a professional discipline with complex processes and activities required for project success. This presents a dilemma. How can the technical and complex nature of project management be interpreted, modified, and presented to primary school students so that they understand all of the separate interconnecting parts, but also apply these in a holistic way to manage a project from beginning to end? While project management professionals may be the best choice to advise on the minimal core components required to manage simple projects, it is teachers that are best placed to jointly create and apply such a learning framework in the classroom. Further research is recommended on bridging the disciplines of education and project management so that each may inform the other in ways that further increase the development of the teaching of project management in primary school settings.

Limitations

The sparseness of peer-reviewed articles necessitated the search for other sources such as websites, web documents, videos, and blogs. While that search was extensive, it was not exhaustive due to the vast amount of information available on the internet. As a result, some relevant literature may have been excluded, which is the primary limitation reported in scoping reviews (Pham et al., 2014 ). The following limitations are related to the nature of scoping reviews. Although a rigorous process was applied using the JBI methodology, PRISMA-ScR checklist, and a scoping review protocol, scoping reviews do not appraise the quality of included studies (Grant & Booth, 2009 ; Levac et al., 2010 ; Rumrill et al., 2010 ). Grant and Booth ( 2009 ) believe that the absence of a quality assessment excludes scoping reviews from making recommendations for policy or practice. However, Tricco et al., ( 2018a , 2018b ) argue that the purpose of scoping reviews is to characterise the literature rather than assess the quality of included studies. Further, scoping reviews are often a precursor to more rigorous knowledge synthesis methods, such as systematic reviews, which do assess quality (Munn et al., 2018 ; Peters et al., 2020 ). Finally, as the information presented in scoping reviews provides more breadth than depth, this review only sought to present the extent, range and nature of the literature rather than a detailed analysis (Tricco et al., 2016 ). Future research may narrow the focus of the topic to include more specific research questions.

This scoping review sets the foundation for a deeper discussion and further research on the topic of teaching project management to primary school children. While the literature revealed that project management is being taught to a certain degree in the primary school classroom, several unanswered questions remain. How can project management be taught holistically to enable students to manage a project successfully from beginning to end? What project management skills should be introduced to primary school children, and at which year level? What can the perspectives of educators add to the effective teaching of project management? Is there a role for project management practitioners to play in informing how project management is taught in a primary school setting? The lack of research studies highlights the need for more empirical investigation in this area. Qualitative and quantitative studies are needed that examine the teaching of project management in primary schools, and the effectiveness of comprehensive approaches to teaching project management in contrast to less comprehensive approaches that focus on these skills in isolation. It is hoped that this scoping review will assist researchers, educators, and project management practitioners to understand more fully the current literature on project management teaching approaches in primary schools. Collaboration between educators and project management practitioners may be the best approach to equip primary school students with the knowledge, skills, and behaviours to manage projects effectively in school, in the community, at work, and throughout life. This represents a significant area of research as project management is one of the most critical skills for students to achieve success in the twenty-first century.

Change history

14 june 2023.

In the method section, the missing citation “Tricco et al., 2018a” is included.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2012). The shape of the Australian Curriculum: Technologies . Retrieved from http://docs.acara.edu.au/resources/Shape_of_the_Australian_Curriculum_-_Technologies_-_August_2012.pdf

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2022). Australian Curriculum: Technologies: Foundation Year, Year 1, Year 2, Year 3, Year 4, Year 5, Year 6 (Version 8.4). Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/download?view=f10 . Accessed April 7 2023.

Akinoglu, O. (2008). Assessment of the inquiry-based project application in science education upon Turkish science teachers’ perspectives. Education, 129 (2), 202–215.

Google Scholar

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8 (1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Article Google Scholar

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. The Clearing House, 83 (2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415

Boss, S., & Krauss, J. (2014). Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age (2nd ed.). International Society for Technology in Education.

Boss, S., & Larmer, J. (2018). Project based teaching: How to create rigorous and engaging learning experiences . ASCD.

Buck Institute for Education. (2018). A framework for high quality project based learning . Retrieved from https://hqpbl.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/FrameworkforHQPBL.pdf . Accessed Feb 8 2022.

Cicmil, S., & Gaggiotti, H. (2018). Responsible forms of project management education: Theoretical plurality and reflective pedagogies. International Journal of Project Management, 36 (1), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.07.005

Clark, A.-M. (2006). Changing classroom practice to include the project approach. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 8 (2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1084959.pdf

D’Orio, W. (2009). The power of project learning: Why new schools are choosing and old model to bring students into the 21st century. Scholastic Administrator , (May 2009), 50–54. Retrieved May 16, 2021, from http://www2.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3751748

Delle-Vergini, S., Eacersall, D., Mustafa, A., Dann, C., & Chakraborty, S. (2023). Teaching project management to children in primary school: A scoping review protocol. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13041800

Digital Technologies in Focus. (2020). Teaching and supporting project management in the classroom F-6 . Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/6640/project-management-f-6.pdf . Accessed April 7 2023.

Edwards, K. M. (2000). Everyone’s guide to project planning: Tools for youth . Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED456118 . Accessed April 7 2023.

Fleer, M. (2016). Technologies for children . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Folsom, C. T. (2000). Managing choice: Helping teachers facilitate decision making, planning, and self-evaluation with students [Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University]. ProQuest One Academic.

French, D. (2018). It’s high time for change in our accountability systems. Education Week . Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-its-high-time-for-change-in-our-accountability-systems/2018/02 . Accessed Sept 6 2020.

Garfein, S. J., & Noeldner, J. (2011). Washington State breakthrough: Project management for high school students . Project Management Institute.

Ginevri, W., & Trilling, B. (2017). Project management for education: The bridge to 21st century learning . Project Management Institute.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26 (2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Kerzner, H. (2010). Project management best practices: Achieving global excellence (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Kerzner, H. (2022). Project management: A systems approach to planning, scheduling, and controlling (13th ed.). Wiley.

Khalil, H., Bennett, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., & Peters, M. (2020). Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 18 (1), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000202

Knoll, M. (2012). I had made a mistake: William H. Kilpatrick and the project method. Teachers College Record, 114 (2), 1–45.

Konstantinou, E. (2015). Professionalism in project management: Redefining the role of the project practitioner. Project Management Journal, 46 (2), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21481

Krajcovicova, B., & Capay, M. (2012). Project based education of computer science using cross-curricular relations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47 (2012), 854–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.747

Lalonde, P.-L., Bourgault, M., & Findeli, A. (2010). Building pragmatist theories of PM practice: Theorizing the act of project management. Project Management Journal, 41 (5), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20163

Larskikh, Z. P., Almazova, I. G., Chislova, S. N., & Chibuhashvili, V. A. (2016). The main trends for arranging project activities in practice of the modern elementary school. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6 (3), 275–281.

Lenz, B. (2016). A way to ensure high-quality project-based learning for all. Education Week . Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-a-way-to-ensure-high-quality-project-based-learning-for-all/2016/09 . Accessed Oct 12 2020.

Lenz, B. (2018). High quality PBL framework on the horizon. Education Week . Retrieved from https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/on_innovation/2018/01/high_quality_pbl_framework_on_the_horizon.html . Accessed Oct 15 2020.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lockwood, C., dos Santos, K. B., & Pap, R. (2019). Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: Scoping review methods. Asian Nursing Research, 13 (5), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.002

Maher, D., & Yoo, J. (2017). Project-based learning in the primary school classroom. Journal of Education Research, 11 (1), 77–87.

McCain, T. (2005). Teaching for tomorrow: Teaching content and probem-solving skills . Corwin Press.

Mintz, A. I. (2016). Dewey’s ancestry, Dewey’s legacy, and the aims of education in Democracy and Education. European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy . https://doi.org/10.4000/ejpap.437

Modzelewski, K., & Urias, D. (2017). PMIEF goes straight to teachers to ask tough questions: do these resources work in your classroom? Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://pmief.org/about-us/news/pmief-goes-straight-to-teachers

Morgan, J., Zhan, W., & Leonard, M. (2013). K-12 project management education: NASA HUNCH projects. American Journal of Engineering Education, 4 (2), 105–118.

Morris, M., Boruff, J. T., & Gore, G. C. (2016). Scoping reviews: Establishing the role of the librarian. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 104 (4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.020

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18 (1), 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Nodzynska, M., Baprowska, A., Ciesla, P., & Bilek, M. (2018). Using a mental map to plan an educational project with science orientation. [Conference proceedings]. Project-based education and other activating strategies in science education XVI. Retrieved from https://pages.pedf.cuni.cz/pbe/files/2019/07/sbornikPBE2018_wos.pdf . Accessed May 8 2022.

Partnership for 21st Century Learning. (2019). Framework for 21st century learning definitions . Retrieved from http://static.battelleforkids.org/documents/p21/P21_Framework_DefinitionsBFK.pdf . Accessed April 7 2023.

Pecore, J. L. (2015). Chapter 7: From Kilpatrick’s project method to project-based learning. In M. Y. Eryaman & B. C. Bruce (Eds.), International handbook of progressive education (pp. 155–171). Peter Lang Publishing.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 407–452). Joanna Briggs Institute.

Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., & Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29 (1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12380

Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5 (4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

Pomelov, V. B. (2021). The William Heard Kilpatrick’s Project Method: On the 150th anniversary of the American educator. Perspectives of Science and Education, 52 (4), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.32744/pse.2021.4.29

Project Management Institute. (2017a). A guide to the project management body of knowledge: PMBOK guide (6th ed.). Project Management Institute.

Project Management Institute. (2017b). Project manager competency development framework (3rd ed.). Project Management Institute.

Project Management Institute. (2017c). Project management job growth and talent gap 2017c-2027 . Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/-/media/pmi/documents/public/pdf/learning/job-growth-report.pdf . Accessed Dec 14 2021.

Project Management Institute. (2021). A guide to the project management body of knowledge: PMBOK guide (7th ed.). Project Management Institute.

Project Management Institute: North Italy Chapter. (2015). Project management kit for primary school: Practice guide for school teachers . Retrieved May 8, 2022, from https://pmi-portugal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/PMIEF-project-management-kit-for-primary-school-practice-guide-for-school-teachers.pdf

Project Management Institute: Portugal. (2020). The methodological kit: Projects from the future [Video]. Vimeo. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://player.vimeo.com/video/471414249

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2013). Project management for social good - Educational programs around the world [Video]. Youtube. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6M68d86XCNo

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2014a). 21st century skills map: Project management for learning . Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://studylib.net/doc/8791387/21st-century-skills-map-%E2%80%93-project-management-for-learning

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2014b). Ensuring project management will be a fundamental skill taught in classrooms around the globe [Video]. Vimeo. Retrieved July 30, 2021, from https://vimeo.com/88761183

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2015a). Project management for learning: A foundational guide to applying project management principles and methods in education . Retrieved September 2, 2021, from https://pmief.org/-/media/files/resources/pmief-foundational-guide-project-management-for-learning.pdf

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2015b). Projects from the future: The kit for primary school . Retrieved July 19, 2021, from https://pmief.org/library/resources/projects-from-the-future-kit-for-primary-school

Project Management Institute Educational Foundation. (2021). New partnerships between PMIEF and DiscoverE and Junior Achievement Europe teach youth project management skills and equip them for 21st century success . Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/about/press-media/press-releases/new-partnerships-between-pmief-and-discovere-and-junior-achievement-europe . Accessed April 7 2023

Portz, S. M. (2014). Teaching project management. Technology & Engineering Teacher, 73 (7), 19–23.

Railsback, J. (2002). Project-based instruction: Creating excitement for learning . Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED471708.pdf . Accessed April 14 2022.

Reitzig, A. (2019). Transforming education: Robotics and its value for next gen learning. Education Week. Retrieved from https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/next_gen_learning/2019/03/transforming_education_robotics_and_its_value_for_next_gen_learning.html . Accessed Sept 6 2020.

Richardson, G. L., & Jackson, B. M. (2019). Project management theory and practice (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Robertson, S. (2012). UK First! PMI EF funds Mill Chase College - Training Secondary students Project Management skills . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1KKdmcxU4E

Rumrill, P. D., Fitzgerald, S. M., & Merchant, W. R. (2010). Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work, 35 (3), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-0998

Student Research Foundation. (2019). Learn project management skills in high school . Retrieved from https://www.studentresearchfoundation.org/blog/learn-project-management-skills-in-high-school/ . Accessed Jan 23 2023.