AP® English Language

The ultimate guide to 2015 ap® english language frqs.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

There were once two neighbors who lived in a small town on the edge of a roaring river. Their houses were set on piles of brick as a precaution for when the river would flood. The bricks had worked for a while, but they began to wear away over the years, and it had left the houses unstable.

One of the neighbors was always conscious of the fact that there could be another flood, so he spent countless hours building and fortifying the foundation of his house. He would get up early on the weekends and go to sleep late on the weeknights to rebuild his home the right way. While he was busy working, his neighbor would sleep in and go out at night, always commenting to his hard-working neighbor that there would be time for work later.

The hours he spent working resulted in a much stronger foundation. He eventually put the house on a set of sturdy stilts that would hold up against the power of a rushing river. He was never able to take his neighbor up on the offer to go out, but that spring when the waters of the river came rushing toward their houses, it all paid off. His house was left standing, while the flood destroyed his neighbor’s house.

Taking your AP® Language test puts you in the unique situation to choose your path. You can be like the man who put off preparing, going into the test blind. Or you can be like the man who spent long hours in preparation, making sure he was ready when the time came.

You want to be like the man who ensured his house had a stable foundation. The foundation you are building, though, will reflect the time you put into learning how to write stellar essays. That foundation includes learning about what the essays require, the best way to write them, and the scoring process. If you prepare yourself for the Free Response Questions, your writing will stand up to the flood, at least metaphorically.

Test Breakdown

The Free Response Questions (FRQs) are the essay portion of the AP® Language exam. The exam itself has two parts, the first is a multiple choice section, and the second is the FRQs. This guide provides an overview, strategies, and examples of the FRQs from the CollegeBoard. There is a guide to the multiple choice here .

The FRQ section has two distinct parts: 15 minutes for reading a set of texts and 120 minutes for writing three essays. The 15 minute “reading period” is designed to give you time to read through the documents for question 1 and develop a thoughtful response. Although you are advised to give each essay 40 minutes, there is no set amount of time for any of the essays. You may divide the 120 minutes however you want.

The three FRQs are each designed to test a different style of writing. The first question is always a synthesis essay – which is why they give you 15 minutes to read all of the sources you must synthesize. The second essay is rhetorical analysis, requiring you to analyze a text through your essay. The third paper is an argumentative essay.

Each essay is worth one-third of the total grade for the FRQ section, and the FRQ section is worth 55% of the total AP® test. Keep that in mind as you prepare for the exam, while the multiple-choice section is hard, the essays are worth more overall – so divide your study time evenly.

The scale for essay scores ranges from 1-9. A score of 1 being illegible or unintelligible, while a score of 9 is going to reflect the best attributes and aspects of early college level writing. You should be shooting to improve your scores to the passing range, which is 5 or above. Note that if you are struggling with the multiple choice section, a 9-9-9 on the essays can help make up for it.

The Tale of Three Essays

If you are currently taking an AP® class, you have probably experienced the style and formats of the three assignments. You may have learned about the specifics of the different types of essays in class, and you may have already found out which of the three is easiest for you. However, you must possess skill in all three to master the AP® test.

The First Essay (Synthesis)

The first essay on the test is going to be the synthesis essay . This essay can be the trickiest to master, but once you do get the hang of it, you will be one step closer to learning the others. The synthesis requires you to read six texts, which can be poems, articles, short stories, or even political cartoons.

Once you have read and analyzed the texts, you are asked to craft an argument using at least three of the documents from the set. The sources should be used to build and support your argument, and you must integrate them into a coherent whole.

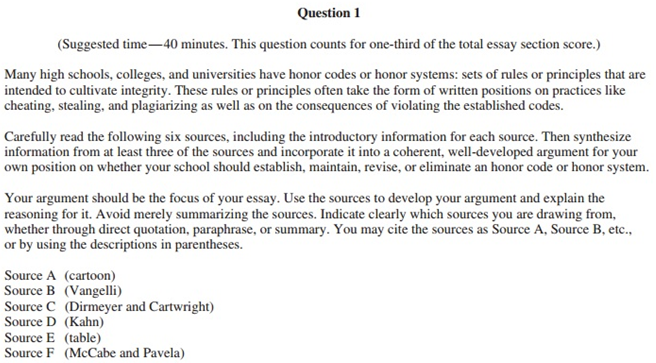

On the 2015 FRQ section of the AP® exam, the synthesis essay focused on university honor codes. The complete prompt for the section is below:

If we break down the task it is asking you to use the six sources to create a “coherent, well-developed argument” from your own position on whether or not schools should create, maintain, change, or eliminate the honors system. As you read this you might have some experience with the idea of honor codes; perhaps you have one from your high school. You can use that experience, but your response needs to focus on the given texts.

To find the actual documents you can go here . Taking a look at the documents will provide some context for the essay samples and their scores.

The question is scored on a scale from 1-9, with nine being the highest. Let’s take a look at some examples of student essays, along with comments from the readers – to break down the dos and don’ts of the FRQ section.

You should always strive to get the highest score possible. Writing a high scoring paper involves learning some practices that will help you write the best possible synthesis essay. Below are three examples taken from student essays.

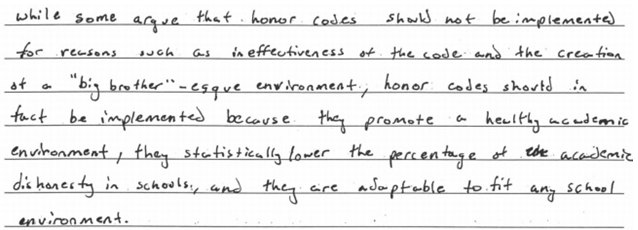

Craft a Well-Developed Thesis

One of the key elements of scoring high on the synthesis essay section of the FRQ is to craft a well-developed thesis that integrates three sources.

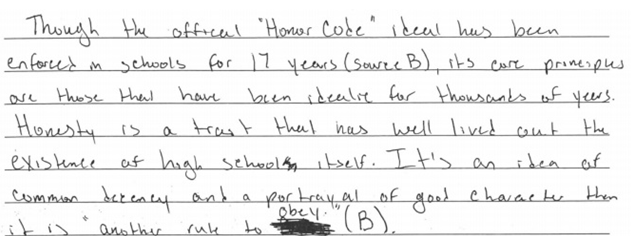

This thesis is from a high scoring essay based off of question 1 from the 2015 FRQ. Take note of some of the good things that this student is doing:

• The essay mentions three examples that they will reference throughout the rest of their essay: promotes a healthy academic environment, statistically lowers the percentage of academic dishonesty in school, and adaptability to school environments.

Part of a strong thesis is the use of three reasons to support the main claim. Each of the reasons that supports your claim should come from a different source text. By using a three-reason support of your claim, you ensure that you have at least the three required sources integrated. Remember : to get a 6 or higher requires 3 or more sources.

• The intro always introduces a counterclaim as a contrast to the thesis. The student points out that, “Some argue that honor codes should not be implemented for reasons such as ineffectiveness of the code and creation of a “big-brother”-esque environment…”

This counterclaim sets the student up to include a paragraph that argues against the claims posed in some of the articles, allowing them to use more of the given sources to their advantage. Using a counterclaim sets them up to write a well-supported essay.

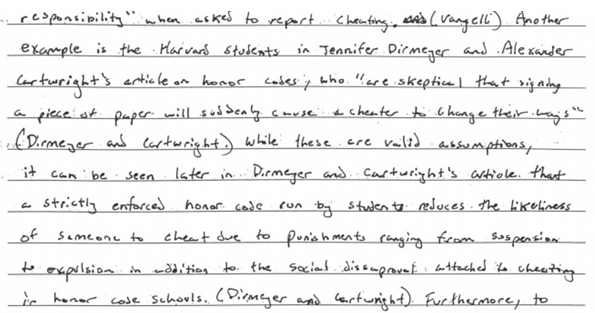

Use Sources Effectively

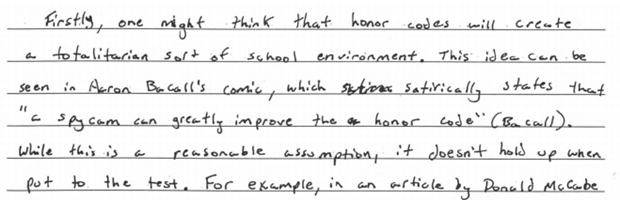

Another essential part of scoring well on the synthesis essay is to utilize the sources effectively. The student demonstrates their command of the text through their second and third paragraphs:

The student seamlessly integrates the different sources in their essay. Notice how in the section above the student can go from one source (Vangell) into information and argument based off of another source (Dirmeger and Cartwright). The ability to use the sources together to form a coherent and cohesive whole is one factor that can set your essay apart from other students’.

Have a Well-Developed Reason for Each Source

Lastly, you will want to ensure that you give a well-developed explanation of the texts when speaking about them. Take this for example:

The student demonstrates deep understanding, and it shows in their writing. You should read a range of texts to prepare for the test. In the example above the student demonstrates a few key skills:

• The student establishes that they understand that Bacall’s comic is satiric, and isn’t meant to seriously. The analysis shows the reader that the student understood the text, and was able to grasp the nuance of the satire.

• The student also establishes that the use of the spy cam is connected to a philosophical idea like totalitarianism – showing the student understands how the text relates to other parts of the world as a whole.

• The student uses the cartoon as a way to jump into his argument, showing how the fears of critics are unwarranted.

There are some practices that students should avoid on FRQ 1 of the test. Students who do these things can expect to receive low scores on their essays, and if you wish to score above a five, you should avoid them at all costs.

Don’t Change Your Argument Midway Through Your Essay.

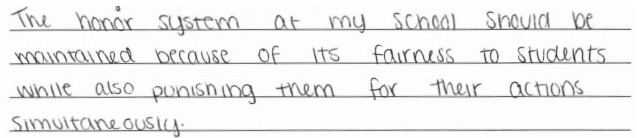

Changing your argument creates confusion and will make your essay weaker overall. Let’s look at a few pieces from a student essay to see how they change their arguments midway through:

Notice that this student talks about the honor system at their school. The student say that it should be maintained in its current form because it is fair, but also punishes students. This statement is taken from the end of the intro paragraph and sets this up as the main crux of the student’s argument – with the idea that they will expand this idea in their paragraphs later.

However, they do not expand the argument with any evidence:

The student continues to talk about how the system at their school is stable, but at the same time, they offer no proof of the actual policy at their school. They use words like “possible” and “fairly” to describe the system – which seems to suggest they don’t have a good grasp of it.

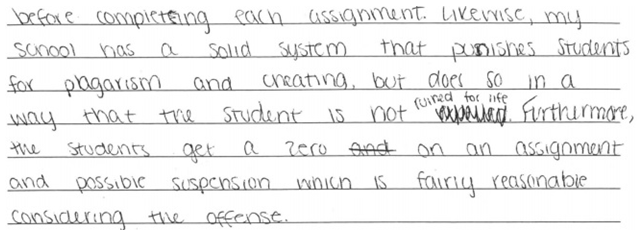

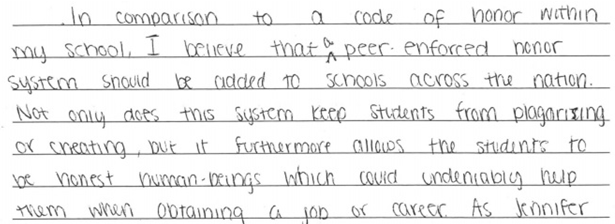

Up to this point, the student has been somewhat consistent, despite being vague and offering no evidence to support the point about how their school’s honor code is a good example of an honor system that works. In the next paragraph, though, the student’s essay takes a complete turn:

In their second to the last paragraph, the student turns from the idea that their school’s honor code is “solid” and instead state that they should change it to incorporate a peer-enforced honor system. This line of argument doesn’t go well with the rest of their essay and even acts to contradict their main points.

Most likely the student added this part to their paper after they realized that they had only utilized a single source. The essay ends with confusion and two sources used inadequately. The lesson to learn from this bad essay is that we should stay consistent in our arguments, sticking to the points we discuss at the beginning.

Don’t Fail to Argue the Prompt

One of the easiest ways to fail question one is to write an essay that doesn’t answer the task in the prompt. If we take a look at a sample of a student’s writing, we can see what it looks like when the aim of the essay isn’t focused on the prompt:

This student is not focusing on whether or not honor codes work. The student is instead giving information and background about honor codes. This explanation goes on for the entire introductory paragraph of the essay, but in the end, the reader has no idea what the student is going to say in the rest of the essay.

The use of information instead of argument is an ineffective strategy for the AP® Language exam, and you should avoid it. Don’t try to make the essay about something other than the assigned prompt. If you stick to the prompt, you will have a better shot at getting a high score like an 8 or 9.

AP® Readers’ Tips:

- Read every text before you start your essay. One of the pitfalls of many students is that they do not use enough sources and try to fit them in after the fact.

- Plan ahead. Ensure that you understand what you are going to be saying and how you will incorporate the different sources into your writing. You will need at least three sources to get above a 6, so ensure you have at least that many mapped in your plan.

The Second Essay (Rhetorical Analysis)

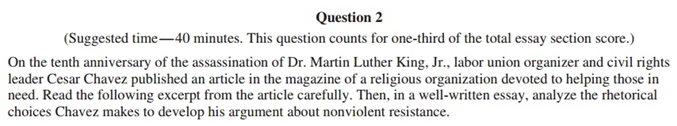

The second essay on the FRQ section is always a rhetorical analysis essay. This essay will focus on analyzing a text for an important aspect of the writing. In the case of the 2015 FRQ, the analysis was supposed to concentrate on rhetorical strategies:

The prompt asks the reader to carefully read the article written by Cesar Chavez and write an essay analyzing the rhetorical choices he uses in the article. Rhetorical choices are simply another term for rhetorical strategies and include things like the rhetorical appeals, and rhetorical devices.

Let’s examine the do’s and don’ts for the second essay.

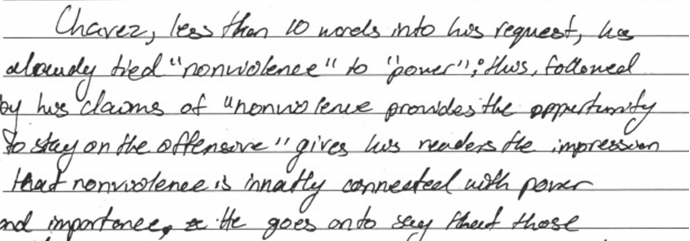

Utilize Specific Examples from the Text in Your Analysis

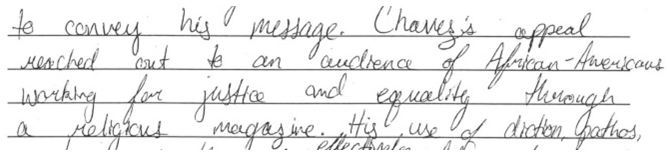

In this high scoring essay, the student goes into their analysis right away. The student points out that Chavez uses precise diction, a rhetorical device, to get his point across. This specific example shows the depth and understanding of the student’s analysis and sets the student up to receive a high score.

Whatever you identify in the text for your analysis, you should be able to point out precisely how it supports your main point. The more depth you can give in your analysis, the more accurate you can be with your comments, the better you will do.

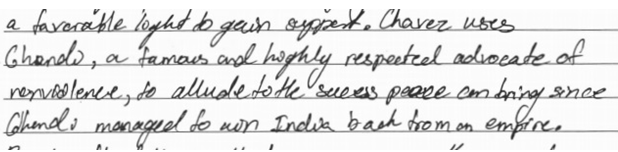

Use Outside Knowledge Effectively to Strengthen Your Argument

The ability to pull in outside knowledge from your classes or books you have read will help enhance your analysis. Let’s take a look at how a student did this on the 2015 exam:

In the example above, the student can provide a more in-depth analysis of Chavez’s words by connecting Chavez’s mention of Gandhi to background knowledge of what Gandhi did in British-controlled India.

The student can provide a comparison of sorts and show how effective Chavez’s comparison is by offering background information about Gandhi’s efforts in India.

Whenever possible, bring in background information that will help with your analysis. It might only seem like extra knowledge about the topic or author, but it could provide some insight into why they chose to write about something or show the full effect of their argument.

Some things to avoid on the literary analysis essay include misreading the passage and providing inadequate analysis of the text.

Don’t Misread the Text

One of the easiest ways to lower your score is to explain something from the text that is incorrect. Let’s look at one of the examples of this from a student essay:

The article mentions that the farm workers union was inspired by the work of Martin Luther King Jr. The student’s misreading of the article led them to write, “Chavez’s appeal reached out to an audience of African-American working for justice and equality…” This analysis is a blatant misread of the passage because nowhere does it signify that Chavez was reaching out to African-Americans specifically.

This type of misread may seem minor, but it indicates that the student’s grasp of the article is less than what they need to analyze it in depth. It will also alert the reader to that fact, and they may look more closely for other signs of misunderstanding and shallow reading.

Don’t Over-simplify Your Points

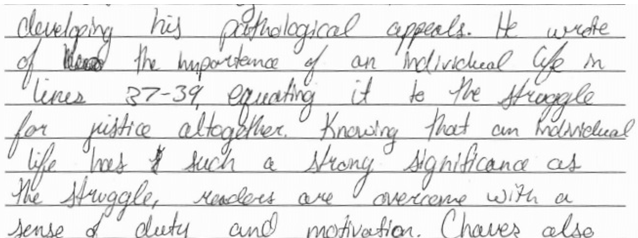

You will want to ensure that your analysis is detailed and gets to the very root of the text. Here is an example of simple analysis from a student:

The student references lines from the text, but the student does not go into detail about what those lines say, nor does the student elaborate on why “…readers are overcome with a sense of duty and motivation.” This simplistic analysis of the text leaves a lot to be desired, and it received a low score because it didn’t provide the necessary details to analyze the text accurately.

You should elaborate on each piece of evidence that you bring forth from the text, and be specific about what in the text you are analyzing. The more you pay attention to the smaller details, the better your score will be in the long run.

AP® Readers’ Tips

- Pay attention to both the holistic (overall) and analytic (particular) views of the piece. You will need to understand both the text as a whole and the specific parts of the text to analyze it effectively.

- Don’t just analyze the rhetoric used, but instead connect the rhetoric to the specific purpose that Chavez hopes to achieve through his speech. This rule applies to any rhetorical analysis essay.

The Third Essay (Argument)

The third and last essay of the FRQ does not respond to a particular text. Instead, the prompt focuses on crafting an argument about a particular issue. Your essay will need to argue a particular position, though most of the questions put forth by the exam will not be simple either/or questions.

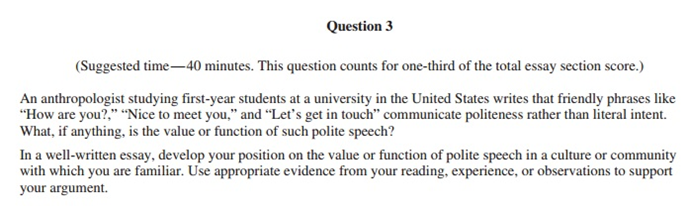

Let’s look at the prompt for the third essay from 2015:

Before we get into the do’s and don’ts of the essay, let’s talk about the particular challenge of this task. You are presented with a scenario, in this case, it deals with small talk, and you are asked to create an argument about that issue.

For 2015, the scenario asks you to argue what value or function you see in small or “polite” talk. You are asked to reference a culture or community you are familiar with, and use evidence from some sources.

A few of the most important things you can do to ensure you score well on the essay include clearly articulating your thesis and use every example to support your main claim.

Clearly Articulate Your Thesis

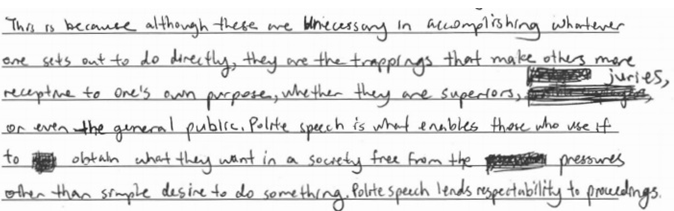

Like with the synthesis essay a clear thesis is important for the argumentative essay. The thesis should be clear in articulating the essay’s claim, and it should demonstrate that the student understood the requirements of the prompt. Let’s examine a well-written thesis statement:

The student, in this case, chose to argue that polite speech serves the purpose of making others more receptive to your purpose. The student then points out three specific situations where polite speech matters: when speaking to superiors, juries, and the general public.

At the end of the thesis statement, the student makes plain the exact nature of the exchange of polite speech for the desired goal. The clarity of their speech and the depth of their understanding is made clear by their command of language.

Use Examples to Support Main Claim

The best essays are going to use all of their examples to support their main claim. In the case of the third essay, the student sets the essay up so that every example will support the idea that polite speech works as an exchange between those with power and those seeking their purpose.

Let’s take a look at one example of how this support works:

The student ensures that they are supporting their main claim. The student is very explicit in tying the example back to the claim with phrases like, “polite speech is an expectation in an environment like school”.

The student points out that there is an expectation of polite speech, and then shows what would happen if polite speech wasn’t used, “…without its implementation, students’ words, and by extension, requests or queries would be disregarded.” This evidence shows that not only is this type of speech required in a school setting but that it is what allows people to get what they want.

This passage demonstrates the level of depth and connection you must make from your evidence to your claim if you want to score well on the third essay of the FRQ. Keep the relationship in mind, and ensure that all your examples explicitly support your claim.

If we take a look at the essay samples from 2015, there are few examples that stand out as don’ts. In particular, you should avoid circular reasoning, and a failure to use variety in your sentences and writing.

Don’t be Unclear in Your Writing

When you are making an argument, and it is based solely on your experiences and reasoning, it can be easy to get bogged down in the details and fail to write a clear well-reasoned essay. You need to take your time and ensure you use clear, well-reasoned logic in your essay.

Let’s take a look at a sample from an essay that has circular reasoning:

The essay doesn’t have a clear, logical path. The thesis statement that polite speech is polite doesn’t add anything to the discussion of the value of polite speech. Their essay is set up by this reasoning to fail. You should avoid circular arguments and logical fallacies at all costs in your argumentative essay.

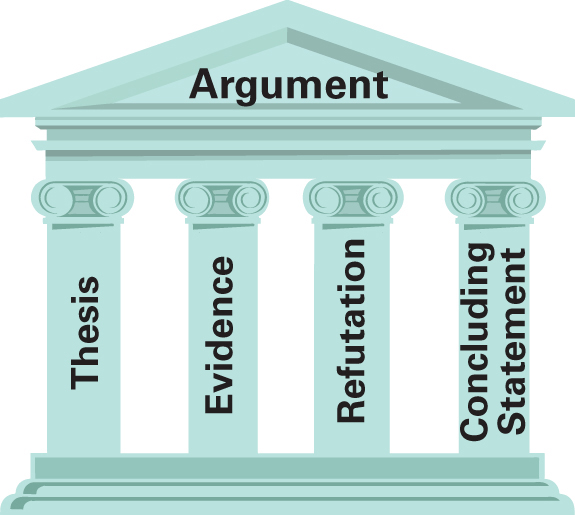

There is a three-part process to creating an argument and avoiding the mistakes from the sample above. Arguments have three main parts:

• Claim: What you are arguing is true.

• Warrant: Your explanation and reasoning for why it is true.

• Evidence: The proof that your warrant uses to prove your claim.

Without any of these three parts any argument is incomplete, and like the sample above – an argument that is incomplete will fail to earn you a high score.

Don’t use a Repetitive Sentence Structure

It seems simple, but many students use simple and repeated sentence structure. You don’t want your writing to become repetitive, so instead try to create variety. Let’s take a look at a student that used repetition too often:

Now the mistake this writer makes may have been done by accident, but it perfectly represents the problem of repetitive structure. It would be advised that you reread your essay before time is up to ensure that you don’t have any repetitions this obvious (In short…In short. above).

This problem can be solved by using a variety of sentence structures, lengths, and formations. You should work diligently as your practice to vary all the elements of your sentences and work to elevate the diction (word choice) you use to make it more formal and academic.

- Keep track of all parts of the prompt. One of the easiest ways to drop points is to forget to answer an important aspect of the prompt. In the case of the 2015 prompt, the essay needs to discuss both a community that is familiar with the student and the value of “polite” speech in that community.

- Try to reference literary examples in your writing. There wasn’t much opportunity to reference readings in the 2015 prompt, but if you can reference the different literature you have read as evidence, it can help boost your scores.

General AP® Readers’ Tips

• Make a plan. One of the best things you can do for any essay you are writing under a time crunch is make a thought-out plan. Sometimes, in the heat of writing, it is easy to forget where we are in our arguments. Having a simple outline can save you from that misfortune.

• Answer the question in your introduction, and be direct. Directly answering the prompt is one of the easiest ways to ensure you get a higher score.

• Clearly, indent your paragraphs, and ensure that you always have an easy to navigate structure. Topic sentences are a must, so make sure those figure into your structure.

• Use evidence especially quotes from the texts, and explain what they mean. You need to make an explicit connection between the evidence you use, and how it supports your points.

• Part of all great writing is variety. Vary your sentence structures, don’t make all of your sentences short or choppy, but instead try to inject some creativity into your writing. Utilize transitions, complex sentences, and elevated diction in your writing.

• Use active voice, and make every word add to the paper as a whole. Avoid fluff; you don’t want your paper to look bad because you are trying to pad your word count.

Wrapping up the Ultimate Guide to 2015 AP® English Language FRQs

Now that you better understand the expectations of the AP® Language and Composition FRQ section, you are one step closer to getting your five on the exam. Take what you have learned in this guide, and work on applying it to your writing. So, now it is time to go practice to perfection.

If you have any more tips or awesome ideas for how to study for the AP® Lang FRQ add them in the comments below.

Looking for AP® English Language practice?

Kickstart your AP® English Language prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Interested in a school license?

Bring Albert to your school and empower all teachers with the world's best question bank for: ➜ SAT® & ACT® ➜ AP® ➜ ELA, Math, Science, & Social Studies aligned to state standards ➜ State assessments Options for teachers, schools, and districts.

Burrell, Colleges Need Honor Codes

The following student essay contains all the elements of a proposal argument. The student who wrote this essay is trying to convince the college president that the school should adopt an honor code —a system of rules that defines acceptable conduct and establishes procedures for handling misconduct.

COLLEGES NEED HONOR CODES

MELISSA BURRELL

Thesis statement

Today’s college students are under a lot of pressure to do well in school, to win tuition grants, to please teachers and family, and to compete in the job market. As a result, the temptation to cheat is greater than ever. At the same time, technology, particularly the Internet, has made cheating easier than ever. Colleges and universities have tried various strategies to combat this problem, from increasing punishments to using plagiaris m- detection tools such as Turnitin.com . However, the most comprehensive and effective solution to the problem of academic dishonesty is an honor code, a campu s- wide contract that spells out and enforces standards of honesty. To fight academic dishonesty, colleges should institute and actively maintain honor codes.

Explanation of the problem: Cheating

Although the exact number of students who cheat is impossible to determine, two out of three students in one recent survey admitted to cheating (Grasgreen). Some students cheat by plagiarizing entire papers or stealing answers to tests. Many other students commit s o- called lesser offenses, such as collaborating with others when told to work alone, sharing test answers, cutting and pasting material from the Internet, or misrepresenting data. All of these acts are dishonest; all amount to cheating. Part of the problem, however, is that students are often unsure whether their decisions are or are not ethical (Balibalos and Gopalakrishnan para. 1). Because they are unclear about expectations and overwhelmed by the pressure to succeed, students can easily justify dishonest acts.

Explanation of the solution: Institute honor code

An honor code solves these problems by clearly presenting the rules and by establishing honesty, trust, and academic honor as shared values. According to recent research, “setting clear expectations, and repeating them early and often, is crucial” (Grasgreen). Schools with honor codes require every student to sign a pledge to uphold the honor code. Ideally, students write and manage the honor code themselves, with the help of faculty and administrators. According to Timothy M. Dodd, however, to be successful, the honor code must be more than a document; it must be a way of thinking. To accomplish this, all firs t- year students should receive copies of the school’s honor code at orientation. At the beginning of each academic year, students should be required to reread the honor code and renew their pledge to uphold its values and rules. In addition, students and instructors need to discuss the honor code in class. (Some colleges post the honor code in every classroom.) In other words, Dodd believes that the honor code must be part of the fabric of the school. It should be present in students’ minds, guiding their actions and informing their learning and teaching.

Evidence in support of the solution

Studies show that serious cheating is 25 to 50 percent lower at schools with honor codes (Dodd). With an honor code in place, students cannot say that they do not know what constitutes cheating or that they do not understand what will happen to them if they cheat. Studies also show that in schools with a strong honor code, instructors are more likely to take action against cheaters. One study shows that instructors frequently do not confront students who cheat because they are not sure the university will back them up (Vandehey, Diekhoff, and LaBeff 469) and another suggests that students are more likely to cheat when they feel their instructor will be lenient (Hosny and Fatima 753). When a school has an honor code, however, instructors can be certain that both the students and the school will support their actions.

Benefits of the solution

When a school institutes an honor code, a number of positive results occur. First, an honor code creates a set of basic rules that students can follow. Students know in advance what is expected of them and what will happen if they commit an infraction. In addition, an honor code promotes honesty, placing more responsibility and power in the hands of students and encouraging them to act according to a higher standard. As a result, schools with honor codes often permit unsupervised exams that require students to monitor one other. Finally, according to Dodd, honor codes encourage students to act responsibly. They assume that students will not take unfair advantage of each other or undercut the academic community. As Dodd concludes, in schools with honor codes, plagiarism (and cheating in general) becomes a concern for everyon e— students as well as instructors.

Refutation of opposing arguments

Some people argue that plagiaris m- detection tools such as Turnitin.com are more effective at preventing cheating than honor codes. However, these tools focus on catching individual acts of cheating, not on preventing a culture of cheating. When schools use these tools, they are telling students that their main concern is not to avoid cheating but to avoid getting caught. As a result, these tools do not deal with the real problem: the decision to be dishonest. Rather than trusting students, schools that use plagiaris m- detection tools assume that all students are cheating. Unlike plagiaris m- detection tools, honor codes fight dishonesty by promoting a culture of integrity, fairness, and accountability. By assuming that most students are trustworthy and punishing only those who are not, schools with honor codes set high standards for students and encourage them to rise to the challenge.

Concluding statement

The only lon g- term, comprehensive solution to the problem of cheating is campu s- wide honor codes. No solution will completely prevent dishonesty, but honor codes go a long way toward addressing the root causes of this problem. The goal of an honor code is to create a campus culture that values and rewards honesty and integrity. By encouraging students to do what is expected of them, honor codes help create a confident, empowered, and trustworthy student body.

Works Cited

Balibalos, K. and J. Gopalakrishnan. “‘OK or Not?’ A New Poll Series about Plagiarism.” WriteCheck , 24 Jul. 2014, en.writecheck.com/ blog/ 2013/ 07/ 24/ ok-or-not-a-new-poll-series-about-plagiarism .

Dodd, Timothy M. “Honor Code 101: An Introduction to the Elements of Traditional Honor Codes, Modified Honor Codes and Academic Integrity Policies.” Center for Academic Integrity , Clemson U , 2010, www.clemson.edu/ ces/ departments/ mse/ academics/ honor-code.html.

Grasgreen, Allie. “Who Cheats, and How.” Inside Higher Ed, 16 Mar. 2012, www.insidehighered.com/ news/ 2012/ 03/ 16/ arizona-survey-examines-student-cheating-faculty-responses.

Hosny, Manar and Shameem Fatima. “Attitude of Students towards Cheating and Plagiarism: University Case Study.” Journal of Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 8, 2014, pp. 74 8– 57.

Vandehey, Michael, et al. “College Cheating: A Twenty Year Follo w- Up and the Addition of an Honor Code.” Journal of College Student Development , vol. 48, no. 4, July/August 2007, pp. 46 8– 80. Academic OneFile , go.galegroup.com/ .

GRAMMAR IN CONTEXT

Will versus Would

Many people use the helping verbs will and would interchangeably. When you write a proposal, however, keep in mind that these words express different shades of meaning.

Will expresses certainty. In a list of benefits, for example, will indicates the benefits that will definitely occur if the proposal is accepted.

First, an honor code will create a set of basic rules that students can follow.

In addition, an honor code will promote honesty.

Would expresses probability. In a refutation of an opposing argument, for example, would indicates that another solution could possibly be more effective than the one being proposed.

Some people argue that a plagiaris m- detection tool such as Turnitin.com would be simpler and a more effective way of preventing cheating than an honor code.

GRE argument essay: Honor code system

Several years ago, Groveton College adopted an honor code, which calls for students to agree not to cheat in their academic endeavors and to notify a faculty member if they suspect that others have cheated. Groveton’s honor code replaced a system in which teachers closely monitored students. Under that system, teachers reported an average of thirty cases of cheating per year. The honor code has proven far more successful: in the first year it was in place, students reported twenty-one cases of cheating; five years later, this figure had dropped to fourteen. Moreover, in a recent survey, a majority of Groveton students said that they would be less likely to cheat with an honor code in place than without. Such evidence suggests that all colleges and universities should adopt honor codes similar to Groveton’s. This change is sure to result in a dramatic decline in cheating among college students. Write a response in which you discuss what questions would need to be answered in order to decide whether the recommendation is likely to have the predicted result. Be sure to explain how the answers to these questions would help to evaluate the recommendation.

While it may seem logical at first glance that the honor code system implemented at Groveton College can help prevent the students from cheating, there are several questions need to be answered in the recommendation in order to prove for the validity.

Hi, I thought your essay was pretty good. Your writing is generally clear, but you do have a lot of mistakes in usage and some missing words here and there. Try to use more transitions to make your writing flow better and sound less choppy.

Your arguments were valid I think. One additional argument you could make is that the survey question seemed flawed. Maybe students felt they could get away with cheating under the honor code system, so they lied in the survey to prevent the system from changing. These students would have a definite incentive to lie, which would invalidate the survey results. Also, maybe the rate of cheating was going down before the change was implemented and the trend simply continued, without the new policy really playing a role at all.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Honor — An Argument on Why Schools Should not Have Honor Codes

An Argument on Why Schools Should not Have Honor Codes

- Categories: Honor

About this sample

Words: 572 |

Published: Oct 22, 2018

Words: 572 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Works Cited

- Austin, G., & McCann, M. (2003). Cheating: An Insider's Report on the Use of Race and Class in the Ivory Tower. Temple University Press.

- Callahan, D. (2004). The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Davis, M., & Ludvigson, H. W. (1995). Additional Thoughts on Academic Integrity: A Reply to Donald McCabe. Journal of Business Ethics, 14(8), 639-647.

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2003). Collegiate Academic Dishonesty Revisited: What Have They Done, How Often Have They Done It, Who Does It, and Why Did They Do It? Electronic Journal of Sociology, 7(3), 1-12.

- McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in Academic Institutions: A Decade of Research. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 219-232.

- McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2004). Honor Codes and Other Contextual Influences on Academic Integrity: A Replication and Extension to Modified Honor Code Settings. Research in Higher Education, 45(3), 365-386.

- Newstead, S., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Armstead, P. (1996). Individual Differences in Student Cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(2), 229-241.

- Pavela, G. (2004). Honor Codes and Other Disciplinary Traditions in American Education. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 36(6), 41-47.

- Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2002). Academic Dishonesty: An Educator's Guide. Psychology Press.

- Xu, Y., & Lo, C. C. (2017). The Relationship Between Honor Codes and Cheating: A Multilevel Analysis of Students’ Perceptions. Ethics & Behavior, 27(2), 148-164.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1030 words

3.5 pages / 1506 words

4 pages / 1842 words

3 pages / 1321 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Honor

I’d be very honored to be inducted to the National Honor Society, and I think I have earned my place. During my years at the high school thus far, I have shown my willingness to work hard in order to achieve my goals. Why I want [...]

As a grateful citizen, I recognize the sacrifices made by our veterans to secure our freedom and uphold the values we hold dear. Their dedication, courage, and selflessness deserve our utmost respect and appreciation. This essay [...]

Duty, honor, country — those are three words that build every individual’s basic character. It molds us for our future and strengthens us when we are weak, helping us to be brave and to face our fears even when we are afraid. It [...]

Archetypes are recurring symbols, themes, or motifs that represent universal patterns of human experience. They serve as a foundation for understanding and interpreting the text, allowing readers to connect with the story on a [...]

Honor killing is also known as “shame killing”. It is basically “killing” or “murder” of family member especially ladies of the family. Family thought that if they allow the victim to live, she will bring dishonor to the family. [...]

Despite being faced with adverse conditions while growing up, humankind possesses resilience and the capacity to accept and forgive those responsible. In The Glass Castle (2005) by Jeannette Walls, Walls demonstrates a [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Structuring a Proposal Argument

In general, a proposal argument can be structured in the following way:

Introduction: Establishes the context of the proposal and presents the essay’s thesis

Explanation of the problem: Identifies the problem and explains why it needs to be solved

Explanation of the solution: Proposes a solution and explains how it will solve the problem

Evidence in support of the solution: Presents support for the proposed solution (this section is usually more than one paragraph)

Benefits of the solution: Explains the positive results of the proposed course of action

Refutation of opposing arguments: Addresses objections to the proposal

Conclusion: Reinforces the main point of the proposal; includes a strong concluding statement

Today’s college students are under a lot of pressure to do well in school, to win tuition grants, to please teachers and family, and to compete in the job market. As a result, the temptation to cheat is greater than ever. At the same time, technology, particularly the Internet, has made cheating easier than ever. Colleges and universities have tried various strategies to combat this problem, from increasing punishments to using plagiarism-detection tools such as Turnitin.com . However, the most comprehensive and effective solution to the problem of academic dishonesty is an honor code, a campus-wide contract that spells out and enforces standards of honesty. To fight academic dishonesty, colleges should institute and actively maintain honor codes. 1

Although the exact number of students who cheat is impossible to determine, two out of three students in one recent survey admitted to cheating (Grasgreen). Some students cheat by plagiarizing entire papers or stealing answers to tests. Many other students commit so-called lesser offenses, such as collaborating with others when told to work alone, sharing test answers, cutting and pasting material from the Internet, or misrepresenting data. All of these acts are dishonest; all amount to cheating. Part of the problem, however, is that students are often unsure whether their decisions are or are not ethical (Balibalos and Gopalakrishnan para. 1). Because they are unclear about expectations and overwhelmed by the pressure to succeed, students can easily justify dishonest acts. 2

An honor code solves these problems by clearly presenting the rules and by establishing honesty, trust, and academic honor as shared values. According to recent research, “setting clear expectations, and repeating them early and often, is crucial” (Grasgreen). Schools with honor codes require every student to sign a pledge to uphold the honor code. Ideally, students write and manage the honor code themselves, with the help of faculty and administrators. According to Timothy M. Dodd, however, to be successful, the honor code must be more than a document; it must be a way of thinking. To accomplish this, all first-year students should receive copies of the school’s honor code at orientation. At the beginning of each academic year, students should be required to reread the honor code and renew their pledge to uphold its values and rules. In addition, students and instructors need to discuss the honor code in class. (Some colleges post the honor code in every classroom.) In other words, Dodd believes that the honor code must be part of the fabric of the school. It should be present in students’ minds, guiding their actions and informing their learning and teaching. 3

Studies show that serious cheating is 25 to 50 percent lower at schools with honor codes (Dodd). With an honor code in place, students cannot say that they do not know what constitutes cheating or that they do not understand what will happen to them if they cheat. Studies also show that in schools with a strong honor code, instructors are more likely to take action against cheaters. One study shows that instructors frequently do not confront students who cheat because they are not sure the university will back them up (Vandehey, Diekhoff, and LaBeff 469) and another suggests that students are more likely to cheat when they feel their instructor will be lenient (Hosny and Fatima 753). When a school has an honor code, however, instructors can be certain that both the students and the school will support their actions. 4

When a school institutes an honor code, a number of positive results occur. First, an honor code creates a set of basic rules that students can follow. Students know in advance what is expected of them and what will happen if they commit an infraction. In addition, an honor code promotes honesty, placing more responsibility and power in the hands of students and encouraging them to act according to a higher standard. As a result, schools with honor codes often permit unsupervised exams that require students to monitor one other. Finally, according to Dodd, honor codes encourage students to act responsibly. They assume that students will not take unfair advantage of each other or undercut the academic community. As Dodd concludes, in schools with honor codes, plagiarism (and cheating in general) becomes a concern for everyone—students as well as instructors. 5

Some people argue that plagiarism-detection tools such as Turnitin.com are more effective at preventing cheating than honor codes. However, these tools focus on catching individual acts of cheating, not on preventing a culture of cheating. When schools use these tools, they are telling students that their main concern is not to avoid cheating but to avoid getting caught. As a result, these tools do not deal with the real problem: the decision to be dishonest. Rather than trusting students, schools that use plagiarism-detection tools assume that all students are cheating. Unlike plagiarism-detection tools, honor codes fight dishonesty by promoting a culture of integrity, fairness, and accountability. By assuming that most students are trustworthy and punishing only those who are not, schools with honor codes set high standards for students and encourage them to rise to the challenge. 6

The only long-term, comprehensive solution to the problem of cheating is campus-wide honor codes. No solution will completely prevent dishonesty, but honor codes go a long way toward addressing the root causes of this problem. The goal of an honor code is to create a campus culture that values and rewards honesty and integrity. By encouraging students to do what is expected of them, honor codes help create a confident, empowered, and trustworthy student body. 7

Works Cited

Balibalos, K. and J. Gopalakrishnan. “‘OK or Not?’ A New Poll Series about Plagiarism.” WriteCheck , 24 Jul. 2014, en.writecheck.com/blog/2013/07/24/ok-or-not-a-new-poll-series-about-plagiarism .

Dodd, Timothy M. “Honor Code 101: An Introduction to the Elements of Traditional Honor Codes, Modified Honor Codes and Academic Integrity Policies.” Center for Academic Integrity , Clemson U , 2010, www.clemson.edu/ces/departments/mse/academics/honor-code.html .

Grasgreen, Allie. “Who Cheats, and How.” Inside Higher Ed, 16 Mar. 2012, www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/03/16/arizona-survey-examines-student-cheating-faculty-responses .

Hosny, Manar and Shameem Fatima. “Attitude of Students towards Cheating and Plagiarism: University Case Study.” Journal of Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 8, 2014, pp. 748–57.

Vandehey, Michael, et al. “College Cheating: A Twenty Year Follow-Up and the Addition of an Honor Code.” Journal of College Student Development , vol. 48, no. 4, July/August 2007, pp. 468–80. Academic OneFile , go.galegroup.com/.

There are some compelling reasons to support self-driving cars. Regular cars are inefficient: the average commuter spends 250 hours a year behind the wheel. They are dangerous. Car crashes are a leading cause of death for Americans ages 4 to 34 and cost some $300 billion a year. In the first 300,000 miles, Google reported that its cars had not had a single accident. Last August, one got into a minor fender bender, but Google said it occurred while someone was manually driving it. 3

After heavy lobbying and campaign contributions, Google persuaded California and Nevada to enact laws legalizing self-driving cars. The California law breezed through the state legislature—it passed 37-0 in the senate and 74-2 in the assembly—and other states could soon follow. The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, which represents big carmakers like GM and Toyota, opposed the California law, fearing it would make it too easy for carmakers and individuals to modify cars to self-drive without the careful protections built in by Google. 4

That is a reasonable concern. If we are going to have self-driving cars, the technical specifications should be quite precise. Just because your neighbor Jeb is able to jerry-rig his car to drive itself using an old PC and some fishing tackle, that does not mean he should be allowed to. 5

As self-driving cars become more common, there will be a flood of new legal questions. If a self-driving car gets into an accident, the human who is “co-piloting” may not be fully at fault—he may even be an injured party. Whom should someone hit by a self-driving car be able to sue? The human in the self-driving car or the car’s manufacturer? New laws will have to be written to sort all this out. 6

How involved—and how careful—are we going to expect the human co-pilot to be? As a Stanford Law School report asks, “Must the ‘drivers’ remain vigilant, their hands on the wheel and their eyes on the road? If not, what are they allowed to do inside or outside, the vehicle?” Can the human in the car drink? Text-message? Read a book? Not surprisingly, the insurance industry is particularly concerned and would like things to move slowly. Insurance companies say all the rules of car insurance may need to be rewritten, with less of the liability put on those operating cars and more on those who manufacture them. 7

At the signing ceremony for California’s self-driving-car law, Governor Jerry Brown was asked who is responsible when a self-driving car runs a red light. He answered: “I don’t know—whoever owns the car, I would think. But we will work that out. That will be the easiest thing to work out.” Google’s Brin joked, “Self-driving cars don’t run red lights.” 8

Neither answer is sufficient. Self-driving cars should be legal—and they are likely to start showing up faster and in greater numbers than people expect. But if that is the case, we need to start thinking about the legal questions now. Given the high stakes involved in putting self-guided, self-propelled, high-speed vehicles on the road, “we will work that out” is not good enough. 9

TIME and the TIME logo are registered trademarks of Time Inc. used Under License.

©2014. Time Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted/Translated from TIME magazine and published with permission of Time Inc. Reproduction in any manner in any language in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited.

Identifying the Elements of a Proposal Argument

- What is the essay’s thesis statement? How effective do you think it is?

- Where in the essay does Cohen identify the problem he wants to solve?

- According to Cohen, what are the specific problems that self-driving cars solve?

- Where does Cohen present his solutions to the problems he identifies?

- Where does Cohen discuss the benefits of his proposal? What other benefits could he have addressed?

- Where does Cohen address possible arguments against his proposal? What other arguments might he have addressed? How would you refute each of these arguments?

- Evaluate the essay’s concluding statement.

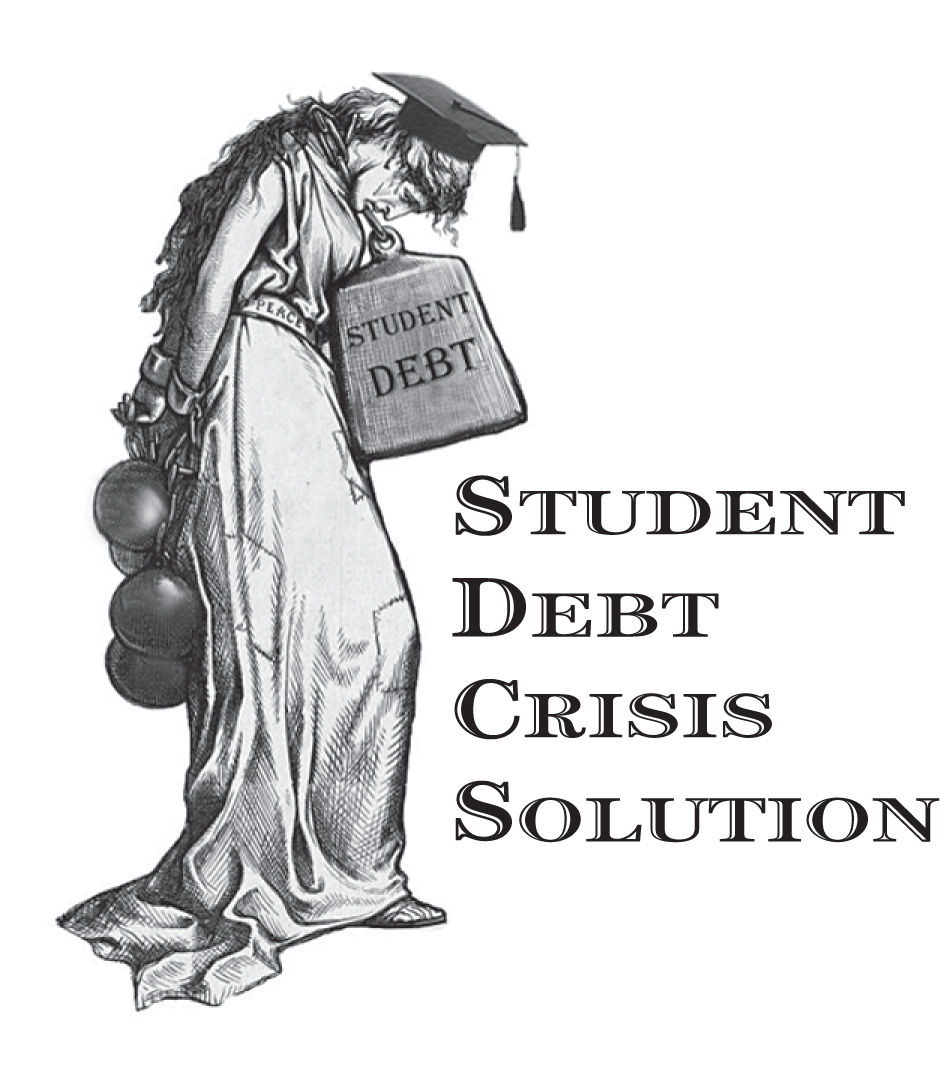

STUDENT DEBT CRISIS SOLUTION

- The editorial cartoon above shows Minerva, an ancient Roman goddess. Consult an encyclopedia to find out more about Minerva. Why do you think this mythical figure is used in this visual?

- Why are Minerva’s wrists chained? Why does she have a sign hanging from her neck? What point is the creator of this image trying to make?

- How could you use this visual to support an argument about student loans? What position do you think it could support?

- What argument does this editorial cartoon make?

The sins of the loan program are many. Let’s briefly mention just five. 6

First, artificially low interest rates are set by the federal government—they are fixed by law rather than market forces. Low-interest-rate mortgage loans resulting from loose Fed policies and the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac spurred the housing bubble that caused the 2008 financial crisis. Arguably, federal student financial assistance is creating a second bubble in higher education.

Second, loan terms are invariant, with students with poor prospects of graduating and getting good jobs often borrowing at the same interest rates as those with excellent prospects (e.g., electrical-engineering majors at MIT).

Third, the availability of cheap loans has almost certainly contributed to the tuition explosion—college prices are going up even more than health-care prices.

Fourth, at present the loans are made by a monopoly provider, the same one that gave us such similar inefficient and costly monopolistic behemoths as the U.S. Postal Service.

Fifth, the student-loan and associated Pell Grant programs spawned the notorious FAFSA form that requires families to reveal all sorts of financial information—information that colleges use to engage in ruthless price discrimination via tuition discounting, charging wildly different amounts to students depending on how much their parents can afford to pay. It’s a soak-the-rich scheme on steroids.

Still, for good or ill, we have this unfortunate program. Wouldn’t loan forgiveness provide some stimulus to a moribund economy? The Wall Street protesters argue that if debt-burdened young persons were free of this albatross, they would start spending more on goods and services, stimulating employment. Yet we demonstrated with stimulus packages in 2008 and 2009 (not to mention the 1930s, Japan in the 1990s, etc.) that giving people more money to spend will not bring recovery. But even if it did, why should we give a break to this particular group of individuals, who disproportionately come from prosperous families to begin with? Why give them assistance while those who have dutifully repaid their loans get none? An arguably more equitable and efficient method of stimulus would be to drop dollars out of airplanes over low-income areas. 7

Moreover, this idea has ominous implications for the macro economy. Who would take the loss from the unanticipated non-repayment of a trillion dollars? If private financial institutions are liable for some of it, it could kill them, triggering another financial crisis. If the federal government shoulders the entire burden, we are adding a trillion or so more dollars in liabilities to a government already grievously overextended (upwards of $100 trillion in liabilities counting Medicare, Social Security, and the national debt), almost certainly leading to more debt downgrades, which could trigger investor panic. This idea is breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity. 8

The demonstrators say that selfish plutocrats are ruining our economy and creating an unjust society. Rather, a group of predominantly rather spoiled and coddled young persons, long favored and subsidized by the American taxpayer, are complaining that society has not given them enough—they want the taxpayer to foot the bill for their years of limited learning and heavy partying while in college. Hopefully, this burst of dimwittery should not pass muster even in our often dysfunctional Congress. 9

- According to Vedder, forgiveness of student debt is “the second-worst idea ever” (para. 2). Why? What is the worst idea?

- In paragraphs 3–6, Vedder examines the weaknesses of the federally subsidized student-loan program. List some of the weaknesses he identifies.

- Why do you think Vedder waits until paragraph 7 to discuss debt forgiveness? Should he have discussed it sooner?

- Summarize Vedder’s primary objection to forgiving student debt. Do you agree with him? How would you refute his objection?

- Throughout his essay, Vedder uses rather strong language to characterize those who disagree with him. For example, in paragraph 8, he calls the idea of forgiving student loans “breathtaking in terms of its naïveté and stupidity.” In paragraph 9, he calls demonstrators “spoiled and coddled young persons” and labels Congress “dysfunctional.” Does this language help or hurt Vedder’s case? Would more neutral words and phrases have been more effective? Why or why not?

- How would Vedder respond to Astra Taylor’s solution to the student-loan crisis ( p. 577 )? Are there any points that Taylor makes with which Vedder might agree?

In other words, nobody ever defaults on a federal student loan again. The whole concept of “default” is expunged from the system. No more collection agencies hounding people with 10 phone calls a night. No more ruined credit and dashed hopes of home-ownership. People who want to enter virtuous but lower-paid professions like social work and teaching won’t be deterred by unmanageable debt. 5

And by calibrating interest and payment rates, the federal government can make the program no more expensive than the current cost of subsidizing loans and writing off unpaid debt. The only losers are the repo men. 6

The concept has been proven to work—Australia and Britain have used it for years—and both liberals and conservatives have reason to get on board. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman proposed the idea all the way back in 1955. 7

Indeed, income-contingent loans are such a good idea, one might wonder why they don’t exist already. Historically, administrative complications have been a major culprit. Until last year, the federal government managed most student loans by paying private banks to act as lenders and then guaranteeing their losses. The IRS would have had to maintain relationships with scores of different lenders, relying on banks for notification of who owes how much and disbursing money hither and yon. Income-contingent loans would have created a huge bureaucratic headache. 8

But in 2010, Congress abolished the old system, cutting out private banks. Now the federal government originates all federal loans. The IRS would have to deal with only one lender: the U.S. Department of Education. In other words, there is a new opportunity to overhaul the way students repay their college debt that didn’t exist until this year. 9

It’s true that students who pay over long periods of time will pay more interest and that the taxpayers will bear the cost of partially forgiven loans. But under the current system the federal government is already eating the cost of defaulted loans, and low-income students who can’t repay loans are often hit with fines and penalties that dwarf the cost of extra interest. 10

When federal loans were first created, nobody imagined they would become standard practice for financing college. As late as 1993, most undergraduates didn’t borrow. Now, two-thirds take on debt, and most of those loans are federal. The average debt load increased over 50 percent during that time. 11

Nor is repayment an isolated problem. One recent study found that the majority of American borrowers—56 percent—struggled with loan payments in the first five years after college. In Britain, by contrast, 98 percent of borrowers are meeting their obligations. 12

Because student loans can almost never be discharged in bankruptcy, defaulted loans can haunt students for a lifetime. Some senior citizens theoretically could have their Social Security checks garnished to make good on old student debt. That is insane. 13

A similar-sounding federal program, called income-based repayment, is now on the books and is scheduled to become somewhat more generous starting in 2014. But the program is administratively complicated, involving income-eligibility caps and requiring students to reapply every year. This points to another major advantage of income-contingent loans: simplicity. 14

Even with the government as the sole source of federal loans, many graduates still have to navigate a thicket of different rates, terms, lenders, consolidation options, and schedules in order to meet their obligations. Some fall behind not because they’re unwilling or unable to pay, but because they can’t get the right check to the right place at the right time. An income-contingent system would remove all of that hassle, making repayment simple and automatic, and setting college graduates free to get on with the important business of starting their lives. 15

The student-loan system has grown into an out-of-control monster tearing at the fabric of civil society. In Chile, student anger over an inequitable, unaffordable, profit-oriented higher-education system led to nationwide pro-tests and violent confrontation just months ago. Now the seeds of similar unrest are sprouting here. 16

Income-contingent loans won’t solve the escalating college prices, state disinvestment in higher education, and overall economic weakness that are driving more students into debt. But they offer a simpler, fairer, more efficient, and more humane way of allowing students to repay loans that aren’t disappearing from the higher-education landscape anytime soon. They could be put in place quickly at no extra cost to the taxpayer. In a dismal fiscal environment, there are few deals this good. 17

The students at the barricades are right to be angry. They didn’t run the economy into the ditch. They didn’t create the system in which a college degree is all but mandatory to pursue a good career, and loans are often unavoidable. But they have to live with it. Income-contingent loans are one way to give them the help they need. 18

- Carey blames the current student-loan problem on years of “greed, inattention, and failed policy” (para. 1). Is he right to assume his readers will agree with him, or should he have provided evidence to support this statement? Explain.

- In paragraph 2, Carey says that income-contingent loans would end “forever” all student-loan defaults. After reading Carey’s explanation, how would you define income-contingent loans ?

- What evidence does Carey present to support his proposal? If income-contingent loans are such a good idea, why hasn’t the government tried them before?

- What kind of appeal does Carey make in paragraph 7? In your opinion, how effective is this appeal?

- Where does Carey address arguments against his proposal? List these arguments. Which argument do you think presents the most effective challenge to Carey’s position? Why?

- In paragraph 16, Carey calls the student-loan system “an out-of-control monster tearing at the fabric of civil society.” In paragraph 18, he says, “The students at the barricades are right to be angry.” Do you think he is exaggerating, or is this strong language justified?

- In paragraph 17, Carey lists problems that income-contingent loans will not solve. Does this paragraph undercut (or even contradict) his statement in paragraph 2 that income-contingent loans would end student-loan defaults? Explain.

But for-profit schools aren’t the only problem. Degrees earned from traditional colleges can also leave students unfairly burdened. 8

Today, a majority of outstanding student loans are in deferral, delinquency, or default. As state funding for education has plummeted, public colleges have raised tuition. Private university costs are skyrocketing, too, rising roughly 25 percent over the last decade. That’s why every class of graduates is more in the red than the last. 9

Modest fixes are not enough. Consider the interest rate tweaks or income-based repayment plans offered by the Obama administration. They lighten the debt burden on some—but not everyone qualifies. They do nothing to address the $165 billion private loan market, where interest rates are often the most punishing, or how higher education is financed. 10

Americans now owe $1.2 trillion in student debt, a number predicted by the think tank Demos to climb to $2 trillion by 2025. What if more people from all types of educational institutions and with all kinds of debts followed the example of the Corinthian 15, and strategically refused to pay back their loans? This would transform the debts into leverage to demand better terms, or even a better way of funding higher education altogether. 11

The quickest fix would be a full-scale student debt cancellation. For students at predatory colleges like Corinthian, this could be done immediately by the Department of Education. For the broader population of students, it would most likely take an act of Congress. 12

Student debt cancellation would mean forgone revenue in the near term, but in the long term it could be an economic stimulus worth much more than the immediate cost. Money not spent paying off loans would be spent elsewhere. In that situation, lenders, debt collectors, servicers, guaranty agencies, asset-backed security investors, and others who profit from student loans would suffer the most from debt forgiveness. 13

We also need to bring back the option of a public, tuition-free college education once represented by institutions like the University of California, which charged only token fees. By the Rolling Jubilee’s estimate, every public two- and four-year college and university in the United States could be made tuition-free by redirecting all current educational subsidies and tax exemptions straight to them and adding approximately $15 billion in annual spending. 14

This might sound like a lot, but it’s a small price to pay to restore America’s place on the long list of countries that provide tuition-free education. 15

To get there, more groups like the Corinthian 15 will have to show that they are willing to throw a wrench in the gears of the system by threatening to withhold payment on their debt. Everyone deserves a quality education. We need to come up with a better way to provide it than debt and default. 16

- Taylor begins her essay by discussing the Corinthian 15. How does this focus help her introduce the problem she wants to solve?

The Department of Education should solve the student debt crisis by

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________.

- What two problems does Taylor discuss? Does she describe them in enough detail? Explain.

- What solutions does Taylor offer? How feasible are these solutions?

- At what points in her essay does Taylor address objections to her proposal? Does she address the most important objections? If not, what other objections should she have addressed?

secondary debt market (para. 3)

crowdfunded donations (3)

unpaid tuition receivables (4)

Look up these terms, and then reread the paragraphs in which they appear. Do these terms help Taylor develop her argument, or could she have made her points without them?

- What assumptions does Taylor assume are self-evident and need no proof? Do you agree? If not, what evidence should Taylor have included to support these assumptions?

Maybe the problem was that I had reached beyond my lower-middle-class origins and taken out loans to attend a small private college to begin with. Maybe I should have stayed at a store called The Wild Pair, where I once had a nice stable job selling shoes after dropping out of the state college because I thought I deserved better, and naïvely tried to turn myself into a professional reader and writer on my own, without a college degree. I’d probably be district manager by now. 8

Or maybe, after going back to school, I should have gone into finance, or some other lucrative career. Self-disgust and lifelong unhappiness, destroying a precious young life—all this is a small price to pay for meeting your student loan obligations. 9

Some people will maintain that a bankrupt father, an impecunious background, and impractical dreams are just the luck of the draw. Someone with character would have paid off those loans and let the chips fall where they may. But I have found, after some decades on this earth, that the road to character is often paved with family money and family connections, not to mention 14 percent effective tax rates on seven-figure incomes. 10

Moneyed stumbles never seem to have much consequence. Tax fraud, insider trading, almost criminal nepotism—these won’t knock you off the straight and narrow. But if you’re poor and miss a child-support payment, or if you’re middle class and default on your student loans, then God help you. 11

Forty years after I took out my first student loan, and thirty years after getting my last, the Department of Education is still pursuing the unpaid balance. My mother, who co-signed some of the loans, is dead. The banks that made them have all gone under. I doubt that anyone can even find the promissory notes. The accrued interest, combined with the collection agencies’ opulent fees, is now several times the principal. 12

Even the Internal Revenue Service understands the irrationality of pursuing someone with an unmanageable economic burden. It has a program called Offer in Compromise that allows struggling people who have fallen behind in their taxes to settle their tax debt. 13

The Department of Education makes it hard for you, and ugly. But it is possible to survive the life of default. You might want to follow these steps: Get as many credit cards as you can before your credit is ruined. Find a stable housing situation. Pay your rent on time so that you have a good record in that area when you do have to move. Live with or marry someone with good credit (preferably someone who shares your desperate nihilism). 14

When the fateful day comes, and your credit looks like a war zone, don’t be afraid. The reported consequences of having no credit are scare talk, to some extent. The reliably predatory nature of American life guarantees that there will always be somebody to help you, from credit card companies charging stratospheric interest rates to subprime loans for houses and cars. Our economic system ensures that so long as you are willing to sink deeper and deeper into debt, you will keep being enthusiastically invited to play the economic game. 15

I am sharply aware of the strongest objection to my lapse into default. If everyone acted as I did, chaos would result. The entire structure of American higher education would change. 16

The collection agencies retained by the Department of Education would be exposed as the greedy vultures that they are. The government would get out of the loan-making and the loan-enforcement business. Congress might even explore a special, universal education tax that would make higher education affordable. 17

There would be a national shaming of colleges and universities for charging soaring tuition rates that are reaching lunatic levels. The rapacity of American colleges and universities is turning social mobility, the keystone of American freedom, into a commodified farce. 18

If people groaning under the weight of student loans simply said, “Enough,” then all the pieties about debt that have become absorbed into all the pieties about higher education might be brought into alignment with reality. Instead of guaranteeing loans, the government would have to guarantee a college education. There are a lot of people who could learn to live with that, too. 19

- In the first three paragraphs of his essay, Siegel discusses the reasons he decided to default on his student loans. How convincing are these reasons? Explain.

- In paragraph 5, Siegel says, “As difficult as it has been, I’ve never looked back.” Does his essay contradict this statement in any way?

- Throughout his essay, Siegel discusses possible objections to his decision. For example, in paragraph 7, he admits that he is “a deadbeat.” List all the objections he attempts to refute. How effectively does he refute them? For example, does he ever convince you that he is not a deadbeat?

- What is Siegel’s opinion of banks? Of colleges and universities? Of the Department of Education? Of American life? How do these opinions color his discussion?

Thesis Statement: ___________________________________________.

Explanation of the Problem: __________________________________.

Explanation of the Solution: __________________________________.

Benefits of the Solution: ______________________________________.

Refutation of Opposing Arguments: ___________________________.

- How does the fact that Siegel is the author of five books and is now almost sixty years of age affect his credibility? Does this information make you more or less likely to see his call to action as reasonable?

So Stephanie didn’t have to take on student loan debt. She chose to. Why should I feel sorry for her? Why should the government lower her interest rates so taxpayers can help her pay those loans back? It’s her debt. Not the taxpayers of America. 8

Other decisions factor into this discussion as well. The Press Herald ran another story a couple days ago, highlighting several students who carried student loan debt. One of the students was a Social Worker who owes $97,000 in student loan debt. A cursory search of the Internet will tell you that social workers don’t earn enough to warrant that kind of debt. The same goes for a Maine student who will owe more than $27,000 for his degree in Philosophy. 9

Seriously, I know Walt Disney told my generation we can “be whatever we want to be” if we “believe in ourselves” but borrowing $27,000 for a career in philosophy … in Maine? That’s a questionable decision at best, and it’s not the government’s fault. 10

The government already stepped in quietly and took over the student loan industry as part of Obamacare, and they already used taxpayer money to lower interest rates on current government student loans to 3.4 percent. Now those taxpayer subsidized interest rates are set to expire, and more than double, and the “gimme gimme” nation doesn’t like it. 11

Naturally, those who want government to take care of them are calling for the interest rates to be held at 3.4 percent, with the taxpayers chipping in for the difference. But make no mistake, even if those rates are held, this won’t be the end of the discussion. Now that the government holds all student loans, they have the opportunity to “bail out students” by forgiving loans. “Occupy” camps in a park near you are already chanting to the beat of the “forgive all student loans” drum, and you can expect that cry to get louder this summer. (It’s warm so they can start “occupying” again.) 12

Now don’t get me wrong. I agree that college costs are too high. And that IS partly government’s fault. Consider the University of Maine, piling on raises for their teachers, while simultaneously jacking up rates for students. In just a few years, university salaries were up 29 percent overall while at the same time tuition costs jumped 30 percent. That’s unacceptable and it’s a problem that needs to be addressed. 13

It’s also the government’s fault that anybody considers a bailout a legitimate solution to our problems. The bank bailouts and Obama’s absolute boondoggle “American Recovery Act” set the precedent and taught my generation that poor decisions and failure can be fixed with a government check. Shame on them for that, and shame on us for looking to government to bail out students now. 14

Ultimately, students and their parents make the decision to borrow money for school. And it’s their responsibility to pay it back. I’m tired of the whining, I’m tired of the blame game, and I’m tired of people relying on government to bail them out. 15

It’s your debt. Pay it yourself. 16

Thesis Statement: _____________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________.

Is your thesis more or less effective than Adolphsen’s? Explain.

- Adolphsen uses two examples to support his point that some people in his generation “want the easy way out” (para. 6). Are these examples enough to support his point? What other evidence could he have provided?

- Could Adolphsen be accused of oversimplifying a complex issue? In other words, does he make hasty or sweeping generalizations ? Does he beg the question ? If so, where?

- Where in his essay does Adolphsen concede a point to those who disagree with him? How effectively does he deal with this point?

- How does Adolphsen characterize those who want student-debt relief? Are his characterizations fair? Accurate? Do these characterizations help or hurt his credibility? Explain.

- In what sense is Adolphsen’s essay a refutation of Lee Siegel’s essay ( p. 580 )?

WRITING ASSIGNMENTS: PROPOSAL ARGUMENTS