Colonial Education

What is colonial education.

The process of colonization involves one nation or territory taking control of another nation or territory either through the use of force or by acquisition. As a byproduct of colonization, the colonizing nation implements its own form of schooling within their colonies. Two scholars on colonial education, Gail P. Kelly and Philip G. Altbach, define the process as an attempt “to assist in the consolidation of foreign rule” (1).

The Purpose of Colonial Education

The idea of assimilation is important to colonial education. Assimilation involves the colonized being forced to conform to the cultures and traditions of the colonizers. Gauri Viswanathan points out that “cultural assimilation [is] … the most effective form of political action” because “cultural domination works by consent and often precedes conquest by force” (85). Colonizing governments realize that they gain strength not necessarily through physical control, but through mental control. This mental control is implemented through a central intellectual location, the school system, or what Louis Althusser would call an “ideological state apparatus.” Kelly and Altbach argue that “colonial schools…sought to extend foreign domination and economic exploitation of the colony” (2) because colonial education is “directed at absorption into the metropole and not separate and dependent development of the colonized in their own society and culture” (4). Colonial education strips the colonized people away from their indigenous learning structures and draws them toward the structures of the colonizers (see Frantz Fanon ).

Much of the reasoning that favors such a learning system comes from supremacist ideas of the colonizers. Thomas B. Macaulay asserts his viewpoints about British India in an early nineteenth century speech. Macaulay insists that no reader of literature “could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” He continues, stating, “It is no exaggeration to say, that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in Sanscrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England.” The ultimate goal of colonial education is this: “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” While all colonizers may not have shared Macaulay’s lack of respect for the existing systems of the colonized, they do share the idea that education is important in facilitating the assimilation process.

The Impact of Colonial Education

Often, the implementation of a new education system leaves those who are colonized with a limited sense of their past. The indigenous history and customs once practiced and observed slowly slip away (see Paul Gilroy: The Black Atlantic ). Growing up in the colonial education system, many colonized children enter a condition of hybridity , in which their identities are created out of multiple cultural forms, practices, beliefs and power dynamics. Colonial education creates a blurring that makes it difficult to differentiate between the new, enforced ideas of the colonizers and the formerly accepted native practices. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o , a citizen of the once colonized Kenya, displays his anger about the damage that colonial education wreaks on colonized peoples. He asserts that the process “annihilate[s] a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves. It makes them see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement and it makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland. It makes them want to identify with that which is furthest removed from themselves” ( Decolonising the Mind 3).

Not only does colonial education eventually create a desire to disassociate with native heritage, but it affects the individual and the sense of self-confidence. Thiong’o believes that colonial education instills a sense of inferiority and disempowerment with the collective psyche of a colonized people. In order to eliminate the harmful, lasting effects of colonial education, postcolonial nations must connect their own experiences of colonialism with other nations’ histories. A new educational structure must support and empower the hybrid identity of a liberated people.

Kelly and Altbach define “classical colonialism” as the process when one separate nation controls another separate nation (3). However, another form of colonization has been present in America for many years. The treatment of the Native Americans falls into the category of “internal colonization,” which can be described as the control of an independent group by another independent group of the same nation-state (Kelly and Altbach 3). Although the context of the situation is different, the intent of the “colonizers” is identical. This includes the way in which the educational system is structured. Katherine Jensen indicates that “the organization, curriculum, and language medium of these schools has aimed consistently at Americanizing the American Indian” (155). She asks: “If education was intended to permit native people mobility into the mainstream, we must ask why in over three centuries it has been so remarkably unsuccessful?” (155). In a supporting study of 1990, census statistics indicate that American Indians have a significantly lower graduation rate at the high school, bachelor, and graduate level than the rest of Americans.

Works Cited

- Jensen, Katherine. “Civilization and Assimilation in the Colonized Schooling of Native Americans.” Education and the Colonial Experience . Ed. Gail P. Kelly and Philip G. Altbach. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1984. 117-36.

- Kelly, Gail P. and Philip G. Altbach. Introduction: “The Four Faces of Colonialism.” Education and the Colonial Experience . Ed. Gail P. Kelly and Philip G. Altbach. New Brunswick: Transaction, 1984. 1-5.

- Macaulay, Thomas B. “Minute on Indian Education.” History of English Studies Page . University of California, Santa Barbara. Web. April 3, 2012. < http://www.english.ucsb.edu/faculty/rraley/research/english/macaulay.html >

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature . Portsmith: Heinemann, 1981.

- Viswanathan, Gauri. “Currying Favor: The Politics of British Educational and Cultural Policy in India, 1813-1854.” Social Text , No. 19/20 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 85-104

Author: John Southard, Fall 1997 Last edited: October 2017

Related Posts

Introduction to postcolonial / queer studies, biocolonialism.

Pingback: Blog Post 1: Night and Day – Women Writing Modernity

What a fantastic piece of work…..in such a short script, you managed to place all the Post-Colonization syndrome which is now a Dominant problem globally….most wars including inter religious conflicts start with Ignorance and With hidden Identity Crisis, becomes a lot worst…I have formulated several Edutainment Platforms to address these issues. Hopefully, if implemented, will help make the world beautiful again…at least, more functional societies….a BIg thank you….what encouragement for concerned citizens….

Awesome piece of work. Beautifully explained. I really agree with the comment that Colonizing governments realize that they gain strength through mental control.

Thanks for sharing this great article

I feel this is among the so much significant info for me. And i’m glad reading your article. However want to statement on some general issues, The web site taste is perfect, the articles is in reality great : D. Excellent task, cheers

many many thanks for sharing this article

Thank you for this enlightening article…very much beneficial

Thank you so much.such good explanation in a minimized understandable form

Write A Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- About Postcolonial Studies

- About This Site

- How to Cite Our Pages

- Calls for Papers

- Authors & Artists

- Critics & Theorists

- Terms & Issues

- Digital Bookshelf

- Book Reviews

- You can contribute

- About the Program

- Emory GPS Events

17 Historical Foundations of Education in the United States: Colonial America to Reconstruction

Historical foundations of education in the united states: colonial america to reconstruction.

In this chapter, we will explore how historical foundations have shaped the trajectory of education in the United States.

Chapter Outline

Colonial america, american revolutionary era, early national era, post civil war and reconstruction, historical foundations.

Education as we know it today has a long history intertwined with the development of the United States. In this section, we will follow historical events through key periods of U.S history to see the forces that left lasting influences on education in the United States.

Introducing The NPR Podcast The Promise a limited-run series about life in public housing, smack in the middle of a city on the rise — stories of a neighborhood in flux, a community defined by its struggles and the growing divide threatening its very existence. You will listen to this podcast throughout the text as an illustration of many key ideas we will discuss.

Season 2: episode 1 – a tale of two schools.

At the beginning of the 2019 school year, Principal Ricki Gibbs knew he had a tough job ahead. Warner Elementary in East Nashville had just landed on Tennessee’s list of lowest performing schools. It had lost so many students that it wasn’t even half full. Gibbs was the fourth principal in six years. Yet, he had seemingly unending enthusiasm and a federal magnet grant to boot. He was confident he could turn Warner around. But what he didn’t anticipate was the neighborhood divide. Warner’s kids are almost all black and most live in poverty, but just about a mile up the road is another public elementary, named Lockeland, whose student body is exactly the opposite. What happens when you have two schools so close together yet so different? And what happens when people in the neighborhood finally start to notice?

Transcript of Podcast

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=533#h5p-1

Public education as we know it today did not exist in the colonies. In the First Charter of Virginia in 1606, King James I set forth a religious mission for investors and colonizers to disseminate the “Christian Religion” among the Indigenous population, which he described as “Infidels and Savages.” His colonial and educational mission would impact settlement and education in America for centuries. Next, we will explore how education began evolving in Puritan Massachusetts and the Middle and Southern Colonies during the colonial period.

Puritan Massachusetts

Puritans in Massachusetts believed educating children in religion and rules from a young age would increase their chances of survival or, if they did die, increase their chances of religious salvation. Puritans in Massachusetts established the first compulsory education law in the New World through the Act of 1642 , which required parents and apprenticeship masters to educate their children and apprentices in the principles of Puritan religion and the laws of the commonwealth. The Law of 1647 , also referred to as the Old Deluder Satan Act , required towns of fifty or more families to hire a schoolmaster to teach children basic literacy. Because of similar religious beliefs and the physical proximity of families’ residences, formal schooling developed quickly in the commonwealth of Massachusetts. Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania followed in Massachusetts’ footsteps, passing similar laws and ordinances between the mid- and late-seventeenth century (Cremin, 1972).

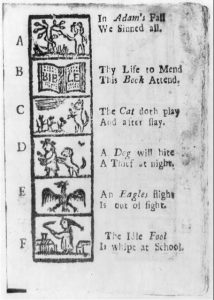

During this time, children learned to read at home using the Holy Scriptures and catechisms (small books that summarized key religious principles) as educational texts. The primers that were used “contained simple verses, songs, and stories designed to teach at once the skills of literacy and the virtues of Christian living” (McClellan, 1999, p. 3).

The importance of faith, prayer, humility, rewards of virtue, honesty, obedience, thrift, proverbs, religious stories, the fear of death, and the importance of hard work served as major moral principles featured throughout the texts. When Indigenous people were depicted or mentioned in texts, they were portrayed as “savages and infidels,” needing salvation through English cultural norms.

Another form of education occurred in dame schools . Where available, some parents sent their children to a neighboring housewife who taught them basic literacy skills, including reading, numbers, and writing. Because families paid for their children to attend dame schools, this form of education was mainly available to middle-class families. Teaching aids and texts included Scripture, hornbooks, catechisms, and primers (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

More expensive than dame schools, Latin grammar schools were also available. The first Latin grammar school was established in Boston in 1635 to teach boys subjects like classical literature, reading, writing, and math at what we would consider the high school level today in preparation to attend Harvard University (Powell, 2019).

The Middle and Southern Colonies

In Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, town or village schooling was not as common. Their populations were sparser, and they focused more on economic opportunities for survival than religion. Education was considered a private matter and a responsibility of individual parents, not the government. Schooling was seen as a service that should be paid by the users of that service, creating a stratified system of education where wealthy families had access to schooling and others did not. Wealthier parents often sent their children to English boarding schools or paid for private schooling in the colonies. Wealthy families also sent their children to parson schools , operated by a highly educated minister who opened his home to young scholars and often taught secular subjects. Education for the poor was usually limited to the rudiments of basic literacy learned in the home or occasionally at church.

Charity schools , often referred to as “endowed ‘free’ schools” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009), were occasionally established when an affluent individual made provisions in his or her will, including land, to construct and manage a school for the poor. In addition, field schools were occasionally built in rural areas. Named after the abandoned fields in which they were built, these schoolhouses offered affordable education to students. The teacher’s salary came from fees students’ families paid, and teachers often boarded with a local family while serving a field school. These schools were also called rate schools, subscription schools, fee schools, and eventually district schools (Urban & Wagoner, 2009).

In Colonial America, education in the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies was heavily stratified and remained out of reach for most inhabitants. New England Puritans worked hard to establish schools. Fear, anxiety, and the struggle for survival lent urgency to their quest for cultural transmission, which helps us understand their desire for formal schooling. Table 3.2 summarizes the main forms of schooling in Colonial America.

Table 3.2: Forms of Schooling in Colonial America

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=533#h5p-2

After the American Revolution, our new country was establishing its systems and identity. Many key Founders believed public education was a prerequisite in a republic. Three groups had distinct post-revolutionary plans for education and schooling, all of which were intended to serve as part of the founding process: Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and the lesser known Democratic-Republican Societies.

Federalists

Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and John Adams, among other Federalists , focused on building a new nation and a new national identity by following the new Constitution, which consolidated power in a new federal government. The Federalists supported mass schooling for nationalistic purposes, such as preserving order, morality, and a nationalistic character, but opposed tax-supported schooling, viewing it as unnecessary in a society where elites rule.

Noah Webster was one of the great advocates for mass schooling, and the purposes for which he supported schooling included teaching children not just “the usual branches of learning,” but also “submission to superiors and to laws [and] moral or social duties.” Smoothing out the “rough manners” of frontier folk was very important to Webster. Furthermore, Webster placed great responsibility among “women in forming the dispositions of youth” in order to “control…the manners of a nation” and that which “is useful” to an orderly republic (Webster, 1965, 67, 69-77). Webster’s treatise on education and his spellers (like his 1783 American Spelling Book ) were intended to develop a literate and nationalistic character to shape useful, virtuous, and law-abiding citizens with strong attachments to Federalist America.

Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalists , on the other hand, were opposed to a strong central government, preferring instead state and local forms of government. The Anti-Federalists believed that the success of a republican government depended on small geographical areas, spaces small enough for individuals to know one another and to deliberate collectively on matters of public concern. Anti-Federalists feared concentrated power.

Thomas Jefferson was an Anti-Federalist. An aristocrat whose genteel lifestyle was bolstered by his violent oppression of enslaved people, Jefferson put forth proposals to educate all white citizens in the state of Virginia. Jefferson proposed a system of tiered schooling. The three tiers were primary schools, grammar schools, and the College of William and Mary. The foundation of his tiered schooling plan included three years of tax-supported schooling for all white children with limited options for a few poor children to advance at public expense to higher levels of education. While he suggested very limited educational opportunities for women, no other key Founder advocated giving high-achieving scholars from poor families a free education. Religion was not a core curricular area in the primary and grammar schools. However, his plans were viewed as too radical by his aristocratic peers, and they correspondingly rejected his state education proposals.

Democratic-Republican Societies

The third group of post-revolution political activists formed several clubs broadly described as the Democratic-Republican Societies during the 1790s. Members of these political clubs included artisans, teachers, ship builders, innkeepers, and working class individuals. They generally supported universal, government-funded schooling, not simply to secure allegiance and order, but also to develop democratic citizen virtue and venues for deliberative learning and opportunities for dissent. The Democratic-Republican Societies viewed education as a means to prepare active citizens for new civic roles, and they considered the government responsible for providing positive benefits to individuals to realize a more fulfilling citizenship through venues such as education.

Table 3.3 summarizes the key differences among these three political groups and how they related to their views of education.

Table 3.3: Federalist, Anti-Federalist, and Democratic-Republican Stances

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=533#h5p-3

During the early- to mid-nineteenth century, the United States was expanding westward, and urbanization and immigration intensified. This period of history was defined by the emergence of the common school movement and normal schools, though conflicts over the organization and control of education continued. This period also saw the advent of higher education.

The Common School Movement

Common schools were elementary schools where all students–not just wealthy boys–could attend for free. Common schools were radical in their status as tax-supported free schooling, but their conservative-leaning curriculum addressed traditional values and political allegiance. Schooling offered increasing opportunities for families’ children, especially working-class families, by teaching basic values including honesty, punctuality, inner behavioral restraints, obedience to authority, hard work, cleanliness, and respect for law, private property, and representative government (Urban & Wagoner, 2009). Horace Mann , Massachusetts’s first Secretary of Education and Whig (formerly Federalist) politician, was the leader of the common school movement, which began in the New England states and then expanded into New York, Pennsylvania, and then into westward states.

The Development of Normal Schools

With the rise of common schools, Horace Mann then turned to how female teachers would be educated. For Mann, the answer was to create teacher training institutions originally referred to as normal schools . A French institution dating back to the sixteenth century, école normale was the term used to identify a model or ideal teaching institute. Once adopted in the United States, the institution was simply called a normal school.

The first normal school in America was established in Lexington, Massachusetts in 1839 (now Framingham State University). They were primarily used to train primary school teachers, as middle and high schools did not yet exist. The curriculum included academic subjects, classroom management and school governance, and the practice of teaching. Teacher credentialing began and was regulated by state governments. Moreover, this contributed to the professionalization of teaching, and normal schools eventually became colleges or schools of education. Many normal schools eventually became full-fledged liberal arts and research institutes. Catherine Beecher was the first well-known teacher of the time and one of the normal schools’ first teachers.

Because the teaching profession was being feminized, administrators and policymakers viewed this as an opportunity. Men were exiting the profession, and women were typically paid much less, allowing more women to be hired for less money to educate the growing ranks of students as common schools spread westward. Furthermore, once the profession was feminized, teaching became perceived as a missionary calling rather than an academic pursuit. While male policymakers insisted women were better nurturers and more suited to teaching morality and correct behavior in children, framing the discourse of teaching around a calling helped rationalize lower pay for women and fewer advancement possibilities.

Conflicts in the Common School Movement

The common school movement was not without its conflicts. Whigs (formerly Federalists), including Horace Mann, sought to establish state systems of schooling in order to create standardization and uniformity in curricula, classroom equipment, school organization, and professional credentialing of teachers across state schools. Democrats, however, often supported public schooling but feared centralized government, thus opposing the centralization of local schools under the common school movement. The battle between Whigs and Democrats during the nineteenth century represents one of the initial conflicts related to public schooling.

Another important conflict related to the common school movement was the clash between urban Protestants and Catholics. Typically from Protestant backgrounds, common school reformers continued to use the Bible as a common text in classrooms without considering the potential conflict this could generate in diverse communities. Horace Mann advocated using only generalized Scripture in order to prevent offending different sects. However, what appeared to Protestants as a generalization of Christian text was actually very insulting to Catholic immigrants, who were becoming the second largest group of city dwellers at the time. Protestants realized that it was best to reduce the religious content in the common school curriculum, but unhappy Catholic leaders created their own private parochial schools. This conflict generated a greater theoretical acceptance of the separation of church and state doctrine in publicly-funded common schools, though in practice, common schooling continued to infuse Protestant biases for over a century.

Common schools also faced conflict in Southern states, including Jefferson’s Virginia, until after the Civil War. Planters had no interest in disturbing the status quo by educating poor whites or enslaved people. Driven by Southern aristocracy, education continued to be viewed as a private family responsibility and class privilege. In fact, many southern states prohibited educating enslaved people and passed state statutes that attached criminal penalties for doing so, such as the ones below.

Enslaved people have often been depicted in American history textbooks as passive toward their owners. This is a misrepresentation of history. African Americans escaped, committed espionage on plantations, negotiated statuses, and occasionally educated themselves behind closed doors. For enslaved people, education and knowledge represented freedom and power, and once they were emancipated, they continued their relentless quest for learning by constructing their own schools throughout the South, even with minimal resources. Unlike many free whites, African Americans placed an exceptional value on literacy due to generations of bondage.

CRITICAL LENS: WORDS MATTER

You will notice in this chapter that we use the term “enslaved person” instead of “slave.” Part of critical theory involves questioning existing power structures, even in word choice. Recently, academics and historians have shifted away from using the term “slave” and have begun replacing it with “enslaved person” because it places “humans first, commodities second” ( Waldman, 2015, para. 2 ).

Even while slavery continued throughout the South, segregation continued in the North. One of the first challenges to segregation occurred in Boston, Massachusetts. Benjamin Roberts attempted to enroll his five-year-old daughter, Sarah, in a segregated white school in her neighborhood, but Sarah was refused admission due to her race. Sarah attempted to enroll in a few other schools closer to her home, but she was again denied admission for the same reason. Mr. Roberts filed a lawsuit in 1849, Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston , claiming that because his daughter had to travel much farther to attend a segregated and substandard black school, Sarah was psychologically damaged. The state courts ruled in favor of the City of Boston in 1850 because state law permitted segregated schooling. This case would be cited in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1898 and in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=533#h5p-4

Following the Civil War, significant restructuring of political, economical, social, and educational systems in the United States occurred. Schooling continued to be viewed as a necessary instrument in maintaining stability and unity. During this era, education was shaped by increasing influence of the federal government, the beginning of education in the South, the Morrill Acts, and Native American boarding schools.

Increasing Influence of the Federal Government

Elazar (1969) asserted that “crisis compels centralization” (p. 51): when the nation undergoes a calamity, it eventually leads to the federal government exercising extra-constitutional actions on its own will or as a result of demands made by state and local governments. The post-Civil War Era provides one example of this effect. The U.S. Congress established requirements for the Southern states to reenter the Union. Radical Republicans, as they were identified after the Civil War, believed that the lack of common schooling in the South had contributed to the circumstances leading to war, so Congress required Southern states to include provisions for free public schooling in their rewritten constitutions.

Of course, southern states followed through with the requirements and drafted language supporting schools, but they created loopholes like separate and segregated schools. Black schools received substantially lower funding than White schools, creating yet another form of institutionalized racism that would have long-lasting consequences for African American communities.

The Beginning of Education in the South

Following the Civil War, nearly four million formerly enslaved people were homeless, without property, and illiterate. In response, Congress created the Freedmen’s Bureau (officially referred to as the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands). Supervised by northern military officers, the Freedmen’s Bureau distributed food, clothing, and medical aid to formerly enslaved people and poor Whites and created over 1,000 schools throughout the southern states. The Freedmen’s Bureau effectively lasted only for seven years, but it represented a massive federal effort that provided some benefits.

In addition to Freedmen’s schools, Yankee schoolmarms also headed south as missionaries to help educate formerly enslaved people. They sought mutual benefits: to educate the illiterate and simultaneously secure themselves in the eyes of God. As missionaries, female teachers learned that their work was a calling to instill morality in the nation’s students, and this calling was pursued for the good of mankind instead of financial gain. This same missionary status fueled both the migration of teachers westward following national expansion, and the thousands of schoolmarms that migrated to the South to educate formerly enslaved people who, they believed, had to be redeemed through literacy, Christian morality, and republican virtue (Butchart, 2010).

However, African Americans were preemptively educating themselves. Formerly-enslaved people knew the connection between knowledge and freedom. Ignorance was itself oppressive; knowledge, on the other hand, was liberating. Literate African Americans were often teaching children and adults alike and creating their own one-room schoolhouses, even with limited resources. By 1866 in Georgia, African Americans were at least partially financing 96 of 123 evening schools and owned 57 school buildings (Anderson, 1988). The African American educational initiatives caught Northern missionaries off guard:

Many missionaries were astonished, and later chagrined…to discover that many ex-slaves had established their own educational collectives and associations, staffed schools entirely with black teachers, and were unwilling to allow their educational movement to be controlled by the ‘civilized’ Yankees.” (Anderson, 1988, p. 6)

In addition, industrial schools were built in the South for Black Americans. Southern policymakers, northern industrialists, and philanthropic groups partnered to establish industrial schools focused on vocational or trade skills. Southern policymakers benefitted because industrial schools resulted in segregated higher education, which further limited access to equality. Northern industrialists benefited because they gained skilled laborers. Philanthropists believed they were giving Black Americans access to education and jobs.

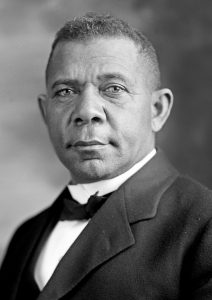

Two African American leaders in the late nineteenth century had different perspectives on newly-developed industrial schools. Booker T. Washington was born an enslaved person in 1856 and grew up in Virginia. He attended the Hampton Institute, whose founder, General Samuel Armstrong, emphasized that “obtaining farms or skilled jobs was far more important to African-Americans emerging from slavery than the rights of citizenship” (Foner, 2012, p. 652-653). Washington supported this view as head of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In his famous 1895 “Atlanta Compromise” speech, Washington did not support “ceaseless agitation for full equality”; rather, he suggested, “In all the things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress” (Foner, 2012, p. 653). Washington feared that if demands for greater equality were imposed, it would result in a white backlash and destroy what little progress had been made.

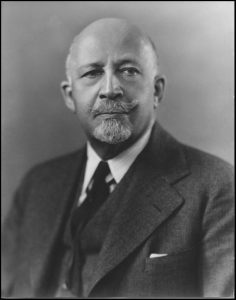

W.E.B. Du Bois viewed the situation differently. Born free in Great Barrington, Massachusetts in 1868, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. He served as a professor at Atlanta University and helped establish the NAACP in 1905 to seek legal and political equality for African Americans. He opposed Washington’s pragmatic approach, considering it a form of “submission and silence on civil and political rights” (Urban & Wagoner, 2009, p. 176).

Critical Lens: The “Value” of Education

The opinions of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois are prevalent in today’s options for education after high school. Some believe that technical schools have a place in society for those who do not choose to, or who are not able to afford, four-year colleges. In essence, that the four-year college experience is not needed to be a contributing member of society. Others believe that one must attend college to expand understanding for future, more “professional” careers. Who is right in these scenarios? What influences where students choose to learn in post-secondary education? It is important to critique the implicit biases we hold regarding others’ educational choices.

Native American Boarding Schools: Cultural Imperialism and Genocide

Using its military, the federal government created a number of Native American boarding schools throughout the country. The first and most famous of these was the Carlisle School, founded in Pennsylvania in 1879. The federal government convinced many Native American parents that these off-reservation boarding schools would educate their children to improve their economic and social opportunities in mainstream America. In reality, this experiment was intended to deculturalize Indigenous children. Supervisors at the boarding schools destroyed children’s native clothing, cut their hair, and renamed many of them with names chosen from the Protestant Bible. The curriculum in these schools taught basic literacy and focused on industrial training, intended to sort graduates of these boarding schools into agricultural and mechanical occupations. A total of 25 off-reservation boarding schools educating nearly 30,000 students were created in several western states and territories, as well as in the upper Great Lakes region. Based in ethnocentrism , or the belief of the White, Protestant mainstream culture that they were superior to other cultures, these boarding schools relied on a harsh form of assimilation, a fundamental feature of common schooling.

One or more interactive elements has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view them online here: https://mtsu.pressbooks.pub/introtoedshell/?p=533#oembed-1

K. Tsianina Lomawaima’s work straddles Indigenous Studies, anthropology, education, ethnohistory, history, legal analysis, and political science. Her scholarship on federal off-reservation boarding schools is rooted in the experiences of her father, Curtis Thorpe Carr, a survivor of Chilocco Indian Agricultural School. Here she discusses the question, Why Boarding Schools?

Education in the United States has a complicated past entrenched in religious, economic, national, and international concerns. In Colonial America, Puritans in Massachusetts knew education would teach children the ways of religion and laws, vital to survival in a new world. Meanwhile, the Middle and Southern Colonies viewed education as a commodity for the wealthy families who could afford it. After the American Revolution, Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and Democratic-Republican Societies all had different perceptions of how schools should be organized to support our newly-established independent nation. In the Early National Era, common schools, normal schools, and higher education grew as education became more widely established. Following the Civil War, the federal government was increasingly involved in education.

Critical Lens: Indigenous Boarding Schools in the News

In the summer of 2021, the dark history of Indigenous boarding schools made headlines as Canadian authorities discovered unmarked graves and remains of children [1] killed at multiple boarding schools for Indigenous children. In July 2021, the U.S. launched a federal probe [2] into our own Indigenous boarding schools and the intergenerational trauma they have caused. These boarding schools are one way that education has been used to oppress and deculturize a particular group of Americans.

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57592243 ↵

- https://www.npr.org/2021/07/11/1013772743/indian-boarding-school-gravesites-federal-investigation ↵

Introduction to Education Copyright © 2022 by David Rodriguez Sanfiorenzo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Postcolonial philosophy of education in the philippines.

- Noah Romero Noah Romero University of Auckland, Faculty of Education

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1575

- Published online: 17 December 2020

Postcolonial philosophies of education in the Philippines emerged from a newly independent government’s desire to unite disparate populations under a common national identity, which was heavily influenced by Western conceptions of personhood and patriotism. The islands collectively known as the Philippines, however, are home to nearly 200 distinct ethnolinguistic groups. The imposition of a universal national identity upon such a diverse populace entails the erasure of identities, knowledge systems, practices, and ways of life that differ from state-imposed norms. Education is a critical site for this subjugation of difference, as evidenced by the state’s imposition of a national curriculum. Yet the national curriculum not only serves to submerge difference, as decolonizing pedagogies and philosophies of education in the Philippines often rise out of collective resistance to the marginalizing aspects of schooling in the region. Postcolonial philosophies of education in the Philippines are, as such, situated within the historical tensions between the national curriculum, the central government’s economic and political agendas, collective calls for human rights, and the philosophies, practices, and knowledge systems of Indigenous peoples (IPs).

- Philippines

- Indigenous education

- postcolonial

- decolonization

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 28 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

Education and Development in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa

Policies, Paradigms, and Entanglements, 1890s–1980s

- Open Access

- © 2020

You have full access to this open access Book

- Damiano Matasci 0 ,

- Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo 1 ,

- Hugo Gonçalves Dores 2

University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

University of coimbra, coimbra, portugal.

- Contributes to the ongoing debate on global and transnational approaches to the history of education

- Deepens our understanding on the interplays between education, internationalism, and empire

- Engages with ongoing research on similar issues in underexplored areas of the world, such as Asia and Latin America

Part of the book series: Global Histories of Education (GHE)

81k Accesses

30 Citations

20 Altmetric

Buy print copy

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Table of contents (11 chapters)

Front matter, introduction: historical trajectories of education and development in (post)colonial africa.

- Damiano Matasci, Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo, Hugo Gonçalves Dores

Education, Living Standards and Social Development

Welfare and education in british colonial africa, 1918–1945.

- Peter Kallaway

Une aventure sociale et humaine : The Service des Centres Sociaux in Algeria, 1955–1962

- Brooke Durham

Education Through Labor: From the deuxième portion du contingent to the Youth Civic Service in West Africa (Senegal/Mali, 1920s–1960s)

- Romain Tiquet

Training Economic Actors

Becoming a good farmer—becoming a good farm worker: on colonial educational policies in germany and german south-west africa, circa 1890 to 1918.

- Jakob Zollmann

Cruce et Aratro: Fascism, Missionary Schools, and Labor in 1920s Italian Somalia

- Caterina Scalvedi

Becoming Workers of Greater France: Vocational Education in Colonial Morocco, 1912–1939

- Michael A. Kozakowski

Engineering Socialism: The Faculty of Engineering at the University of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) in the 1970s and 1980s

- Eric Burton

Entanglements and Competing Projects

Enlightened developments inter-imperial organizations and the issue of colonial education in africa (1945–1957).

- Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo, Hugo Gonçalves Dores

The Fabric of Academic Communities at the Heart of the British Empire’s Modernization Policies

- Hélène Charton

Exploring “Socialist Solidarity” in Higher Education: East German Advisors in Post-Independence Mozambique (1975–1992)

- Alexandra Piepiorka

Back Matter

- Internationalism

- North-South relations

- Global south

- Imperialism

- British Empire

- Vocational Education

About this book

This open access edited volume offers an analysis of the entangled histories of education and development in twentieth-century Africa. It deals with the plurality of actors that competed and collaborated to formulate educational and developmental paradigms and projects: debating their utility and purpose, pondering their necessity and risk, and evaluating their intended and unintended consequences in colonial and postcolonial moments. Since the late nineteenth century, the “educability” of the native was the subject of several debates and experiments: numerous voices, arguments, and agendas emerged, involving multiple institutions and experts, governmental and non-governmental, religious and laic, operating from the corridors of international organizations to the towns and rural villages of Africa. This plurality of expressions of political, social, cultural, and economic imagination of education and development is at the core of this collective work.

Editors and Affiliations

Damiano Matasci

Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo

Hugo Gonçalves Dores

About the editors

Damiano Matasci is Research Fellow at the Institute of Political Studies of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. His research focuses on the history of education in Europe and colonial Africa.

Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo is Professor and Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. He has been working on the historical intersections between internationalism(s) and imperialism, and on the late colonial entanglements between idioms and repertoires of development and of control and coercion in European colonial empires.

Hugo Gonçalves Dores is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. His research addresses educational policies, international organizations activities (CCTA and UNESCO), and State-Church relations in colonial contexts.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Education and Development in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa

Book Subtitle : Policies, Paradigms, and Entanglements, 1890s–1980s

Editors : Damiano Matasci, Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo, Hugo Gonçalves Dores

Series Title : Global Histories of Education

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27801-4

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Education , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-27800-7 Published: 04 January 2020

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-27803-8 Published: 18 September 2020

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-27801-4 Published: 03 January 2020

Series ISSN : 2731-6408

Series E-ISSN : 2731-6416

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIX, 321

Number of Illustrations : 4 b/w illustrations

Topics : Educational Policy and Politics , International and Comparative Education , History of Education , Development and Post-Colonialism , Imperialism and Colonialism

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Colonial Legacy in Indian Education

- Posted September 4, 2013

Ed. Magazine

The magazine of the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

The Move to Make Early Childcare Better — for Kids and Teachers

Embracing the Whole Student, Being Ratchetdemic

Lessons from Refugee Education for Current and Future Pandemics

How refugee education can inform education in other times of uncertainty

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Colonial education creates a blurring that makes it difficult to differentiate between the new, enforced ideas of the colonizers and the formerly accepted native practices. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, a citizen of the once colonized Kenya, displays his anger about the damage that colonial education wreaks on colonized peoples.

Still, education there remains as institutions to cultivate laborers, and the education goals have always been framed in the domains of "developing" and "undeveloped". Education in the post-colonial times presents a process of self-denial (Ntarangwi, 2003), which is the common feature of most education systems in post-colonial countries.

Postcolonial philosophies of education in the Philippines emerged from a newly. independent government's desire to unite disparate populations under a common. national identity, which was ...

This chapter addresses the historical trajectories of education and development in the twentieth century (post)colonial Africa, framing the main goals of this collective book.

From Pre-Colonial to Post-Colonial. Educational Transitions in Southern Asia. Sureshachandra Shukla. This paper is an exercise in comparative education that seeks to take into account not only the differing styles of colonialism in Asia but also the varying styles of indigenous culture, institutions of learning and schooling, and social ...

Education in Africa during the first decade of independence was shaped by several external forces. First was the Report of the Conference of African States on the Development of Education in Africa that was held in Addis Ababa in May 1961, under the joint sponsorship of UNESCO and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) . The central aim of this conference was to provide a ...

of Education: Transnational and Cross-Cultural Exchanges in (Post)Colonial Education (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014). For a comparative assessment, see Peter Kallaway ... During the twentieth century, three phases—or critical junctures—can be identied, during which the economic and social goals of education were profoundly recongured and ...

Their study was partly composed of a historical examination of teacher education in Namibia that found that during colonial times, when the dominant ideologies in circulation were to enforce apartheid-regulated segregation, teachers were trained based on a Christian National Education curriculum that specifically excluded mathematics and ...

A major goal of education was to force the indigenous ... One factor that continued to affect education in the former Spanish colonies post-independence was the high ... on educating the colonial elite. Waldinger finds that people in localities that had a Mendicant mission station during the colonial period had significantly higher educational ...

subaltern history. postcolonialism, the historical period or state of affairs representing the aftermath of Western colonialism; the term can also be used to describe the concurrent project to reclaim and rethink the history and agency of people subordinated under various forms of imperialism. Postcolonialism signals a possible future of ...

Next, we will explore how education began evolving in Puritan Massachusetts and the Middle and Southern Colonies during the colonial period. ... Three groups had distinct post-revolutionary plans for education and schooling, all of which were intended to serve as part of the founding process: Federalists, Anti-Federalists, and the lesser known ...

The same happened with the debates about the usefulness of "native education," at the metropoles and at the colonies. Problems such as the necessity and the utility of the provision of educational services in Africa, for settlers and for the colonial subjects, were the object of numerous appreciations. A diversity of arguments and positions emerged within imperial and international circles ...

2.32 The most characteristic features of French education policy have been : (1) the universal use of French as medium of instruction; (2) relating ad-. vanced education with demand for jobs; (3) strong emphasis on vocational training; (4) progressive assimilation of the curricula and examination of. French teachers.

This chapter addresses the historical trajectories of education and development in the twentieth century (post)colonial Africa, framing the main goals of this collective book. It discusses the ...

Oxford Research Encyclopedias

Damiano Matasci is Research Fellow at the Institute of Political Studies of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. His research focuses on the history of education in Europe and colonial Africa. Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo is Professor and Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Studies at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. He has been working on the historical intersections between ...

A problem-oriented history of education in postcolonial India is presented along with a forecast of India's educational future. The problems of providing quality education in India after 190 years of British rule, which left only l3 percent of the Indian population literate at the time of India's independence in 1947, are discussed. India's postcolonial attempts at modernizing its educational ...

Education during the Pre-colonial period. ... Post-colonial Philippines Education aimed at the full of realization of the democratic ideals and way of life. The Civil Service Eligibility of teachers was made permanent pursuant to R. 1079 in June 15, 1954. A daily flag ceremony was made compulsory in all schools including the singing of the ...

Post Colonial Educational System in the Philippines GROUP 7 Baynas, Emy V. Dulu Rochelle N. Nagashima, Gelieca D. Santos, Trixcie M. Virtudazo, Jaisy V. Republic Act 1079 Republic Act 1079 FUN FACTS TEACHER FUN FACTS FUN FACTS This is the place where the teacher has their picture,

Postcolonial philosophies of education in the Philippines are, as such, situated within the historical tensions between the national curriculum, the central government's economic and political ...

The term "Macaulayism" has now grown to refer to any attempt by a colonizing culture to impose itself on its colonies through education. Almost 70 years after the end of British rule, it's a legacy that Taktse's teachers are still sifting through. For more, read the feature story " East, West, and Ten-drel ." Ed. Magazine.

Purpose: The purpose of this article is to discuss about precolonial and colonial education and the development of the education systems in the postcolonial Africa. The paper will deal with the ...

colonial powers, but it is different from what was introduced by the British. Before the arrival of colonial powers, education in Malaya was non-formal and burdened the cognitive development of students. (Abdullah Sani & P.Kumar, 1990, p.1). The education system during that period was the religious education system (Pondok School).