The World of Work is Rapidly Changing IELTS Essay

The world of work is rapidly changing and employees cannot depend on having the same job or the same working conditions for life. Discuss the possible causes and suggest ways to prepare people to work in the future.

Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant examples from your own knowledge or experience. You should write at least 250 words.

Practice with Expert IELTS Tutors Online

Apply Code "IELTSXPRESS20" To Get 20% off on IELTS Mock Test

This essay was asked on Recent IELTS Exam 20 January 2022 India Question Answers

The World of Work is Rapidly Changing IELTS Essay – Model Essay 1

These days, people’s workplaces are constantly changing and evolving to meet the demands of modern society. Furthermore, the roles and responsibilities of jobs are also undergoing changes to adapt to new ways of working and living. This essay will discuss the possible reasons for these changes and suggest some ways that people can better prepare themselves for their future careers.

Firstly, due to the developments in hi-tech machines and artificial intelligence, millions of people all around the world are losing their jobs and being replaced by automated processes. For example, millions of factory workers have lost their jobs because they have been replaced by machines that are able to do their job quicker and more effectively. Furthermore, as a result of the ever-increasing desire to cut expenses and increase profits, many jobs are being outsourced to countries where the wages are lower. For instance, when a person calls a tech support helpline in an English-speaking country, they will most likely be connected to someone in another country, like India or the Philippines, where the wages are lower.

However, there are a number of ways that people can prepare for changes in their workplaces in the future. Firstly, students preparing to leave high school need to be advised about the sustainability of the career path they are choosing. To illustrate, autonomous vehicles are predicted to replace most delivery and taxi driver jobs in the very near future, so this is not a job that someone should expect to have for a very long time. Furthermore, while some jobs are being replaced by technology, many jobs are simply incorporating technology into their process, and therefore people will need to be able to keep up to date with these changes. To help achieve this, specific courses could be designed to help educate people on the use of modern technology in their workplaces.

In conclusion, although there are many changes in the workplace these days, educating people to carefully choose their career and to keep up to date with modern technology, is the key to avoiding any major problems.

I E L T S XPRESS

The World of Work is Changing Rapidly Essay – Model Essay 2

It is irrefutable that the work scenario is altering at a fast pace. Working conditions are also different and the process of job-hopping is very common. This essay shall delve into the possible causes for these changes and suggest ways to prepare for work in the time to come.

To begin with, the development of science and technology has changed the structure of work. For example, people no longer need to do some heavy work by themselves. Instead, they can use machines. Secondly, competition has become intense and people have to constantly update themselves with the latest materials and methods. Sometimes they cannot compete with the new techno-savvy workforce and so have to change jobs out of compulsion.

Furthermore, we belong to an era of consumerism. Being surrounded by so many choices, people today want to buy new things and for that, they do multiple jobs. In addition, the 24/7 society of today provides us the opportunity to work day and night. For instance, in earlier times, there were very few jobs which were round-the-clock jobs. But, today, globalization has brought in a multitude of options of working day and night. The line between day and night has become dim and people have become workaholics.

There could be many suggestions to prepare for work in the future. People should have a set goal in their mind and get training accordingly. Moreover, it is important to draw a line somewhere. The stress and strain of the fast modern workplace is leading many to nervous breakdowns. In the developed countries, a new term called downshifting has already come where after a certain stage, people are saying ‘no’ to promotions and showing contentment with less. We should also realize that if we stick to one job, then also life can be more stable and we can enjoy our leisure also. ieltsxpress

To put in a nutshell, I pen down saying that, although work conditions are different today and we have a need to update our knowledge regularly, we can plan our life in a meticulous way and have a balance between work and leisure.

Also Check: There is a General Increase in Anti-Social Behaviour Essay

IELTS Writing Task 2 on Jobs – Model Essay 3

In today’s modern world, people tend to change jobs more often than before and don’t want to work permanently in one environment. I would like to explore the sources of this issue and suggest several solutions for future work.

Firstly, due to the global recession, many employers have to downsize and restructure their businesses. This leads to a number of redundant employees being forced to leave their jobs and find other ones. Another reason is that, as living costs are getting higher and higher, people want to earn as much money as they can to meet their needs. Hence, they seek better opportunities and well-paid jobs everywhere, every day. Some also look for new challenges. Last but not least, thanks to new technology, people nowadays are able to access information more easily, including information about job recruiting.

One of my suggestions for this problem is that if we can create a comfortable working environment and build strong relationships between colleagues; and between managers and workers. These will make employees find it harder to leave. To archive this, courses such as leadership training and communication skill training should be carried out to help supervisors lead their team efficiently without causing any stress, and help employees fit inconveniently. ielts xpress

By the way of conclusion, I would like to state that change job is one the remarkable signs of technological times and soft skill training courses possibly help people adapt to the working environment instead of finding a way to escape it.

The Workplace is Changing Rapidly – Model Essay 4

Work culture lately has been dynamically transformed, mainly due to improvements in technology like transport and communication. Job security has become a dicey issue as employees now need to keep themselves updated with the advancements around them. This essay shall further explain the reasons and offer probable solutions. ieltsxpress.com

In the last two decades, we have seen a remarkable spread of technology in all wakes of life. With easy access to the Internet and computers, work has become faster and easier. Innovation of office tools is encouraged everywhere so as to not let anything hinder the growth of trade and commerce. With each task becoming effortless, manual intervention at many places has been reduced. Ergo, rising insecurity is seen among employees. Additionally, employees are expected to multi-task in their jobs making it more difficult for older workers to sustain.

The remedial measures for such a situation are very few as of now. First of all, state-of-the-art employee training centers to help the employees stay well-versed with the high-tech upgradations. To solve this problem from an earlier level, universities should start imparting practical training in their curriculum, with the know-how of current on-the-job scenarios to prepare potential workers better. All this needs to be done as the employees losing their jobs also lose financial security for their families, and it is very difficult to start again from ground zero.

To conclude, I’d say we should accept the ever-changing technological advancements as they’re unlikely to stop. Better would be to equip ourselves and become flexible accordingly so as to welcome such developments.

How The World of Work is Changing – Model Essay 5

It is indeed true that the world has been increasing by loops and bound for a long time and very few employees can handle obstacles in their near future. Because it has some reason. However, to my notion, employees need some specification training for it.

There are various reasons behind why it has increased, first and foremost, in globalization time every company wants to grow fast. Secondly, important roles are being played by studying on the contemporary world. that is why every employee ought to be cognizant of every field. so that he/she can do everything for their job. Moreover, technology has changed every life completely. for instance mobile, internet and computer are very prominent in the work field. it helps the employee to make their job easy. Finally, in today’s time, we can see a person living in India and working for a company located in us.

on contrary, every problem has a solution there is some way which can help employees for their job. to start with they must be taught English because English is a basic requirement for learning any new thing. Moreover, they must be friendly with their peer group members. in addition, management skills, internet, and computer knowledge must be important. these all things give help them in their upcoming time.

To sum up, I firmly believe that there are ample chances in today’s work environment. However, by following some training. we can prepare employees for the near future growth and make spectacular culture.

Ideas for World of Work

Also Check: It is Impossible to help all people in the world IELTS Essay

Oh hi there! It’s nice to meet you.

Sign up to receive awesome content in your inbox, every week.

We promise not to spam you or share your Data. 🙂

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Oh Hi there! It’s nice to meet you.

We promise not to Spam or Share your Data. 🙂

Related Posts

Some Countries Spend a lot of Money to Make Bicycle Usage Easier

Tasks at Home and Work are being performed by Robots

Climate has the Greatest Effect on People’s Way of Life

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Yes, add me to your mailing list

Start typing and press enter to search

Essays About Work: 7 Examples and 8 Prompts

If you want to write well-researched essays about work, check out our guide of helpful essay examples and writing prompts for this topic.

Whether employed or self-employed, we all need to work to earn a living. Work could provide a source of purpose for some but also stress for many. The causes of stress could be an unmanageable workload, low pay, slow career development, an incompetent boss, and companies that do not care about your well-being. Essays about work can help us understand how to achieve a work/life balance for long-term happiness.

Work can still be a happy place to develop essential skills such as leadership and teamwork. If we adopt the right mindset, we can focus on situations we can improve and avoid stressing ourselves over situations we have no control over. We should also be free to speak up against workplace issues and abuses to defend our labor rights. Check out our essay writing topics for more.

5 Examples of Essays About Work

1. when the future of work means always looking for your next job by bruce horovitz, 2. ‘quiet quitting’ isn’t the solution for burnout by rebecca vidra, 3. the science of why we burn out and don’t have to by joe robinson , 4. how to manage your career in a vuca world by murali murthy, 5. the challenges of regulating the labor market in developing countries by gordon betcherman, 6. creating the best workplace on earth by rob goffee and gareth jones, 7. employees seek personal value and purpose at work. be prepared to deliver by jordan turner, 8 writing prompts on essays about work, 1. a dream work environment, 2. how is school preparing you for work, 3. the importance of teamwork at work, 4. a guide to find work for new graduates, 5. finding happiness at work, 6. motivating people at work, 7. advantages and disadvantages of working from home, 8. critical qualities you need to thrive at work.

“For a host of reasons—some for a higher salary, others for improved benefits, and many in search of better company culture—America’s workforce is constantly looking for its next gig.”

A perennial search for a job that fulfills your sense of purpose has been an emerging trend in the work landscape in recent years. Yet, as human resource managers scramble to minimize employee turnover, some still believe there will still be workers who can exit a company through a happy retirement. You might also be interested in these essays about unemployment .

“…[L]et’s creatively collaborate on ways to re-establish our own sense of value in our institutions while saying yes only to invitations that nourish us instead of sucking up more of our energy.”

Quiet quitting signals more profound issues underlying work, such as burnout or the bosses themselves. It is undesirable in any workplace, but to have it in school, among faculty members, spells doom as the future of the next generation is put at stake. In this essay, a teacher learns how to keep from burnout and rebuild a sense of community that drew her into the job in the first place.

“We don’t think about managing the demands that are pushing our buttons, we just keep reacting to them on autopilot on a route I call the burnout treadmill. Just keep going until the paramedics arrive.”

Studies have shown the detrimental health effects of stress on our mind, emotions and body. Yet we still willingly take on the treadmill to stress, forgetting our boundaries and wellness. It is time to normalize seeking help from our superiors to resolve burnout and refuse overtime and heavy workloads.

“As we start to emerge from the pandemic, today’s workplace demands a different kind of VUCA career growth. One that’s Versatile, Uplifting, Choice-filled and Active.”

The only thing constant in work is change. However, recent decades have witnessed greater work volatility where tech-oriented people and creative minds flourish the most. The essay provides tips for applying at work daily to survive and even thrive in the VUCA world. You might also be interested in these essays about motivation .

“Ultimately, the biggest challenge in regulating labor markets in developing countries is what to do about the hundreds of millions of workers (or even more) who are beyond the reach of formal labor market rules and social protections.”

The challenge in regulating work is balancing the interest of employees to have dignified work conditions and for employers to operate at the most reasonable cost. But in developing countries, the difficulties loom larger, with issues going beyond equal pay to universal social protection coverage and monitoring employers’ compliance.

“Suppose you want to design the best company on earth to work for. What would it be like? For three years, we’ve been investigating this question by asking hundreds of executives in surveys and in seminars all over the world to describe their ideal organization.”

If you’ve ever wondered what would make the best workplace, you’re not alone. In this essay, Jones looks at how employers can create a better workplace for employees by using surveys and interviews. The writer found that individuality and a sense of support are key to creating positive workplace environments where employees are comfortable.

“Bottom line: People seek purpose in their lives — and that includes work. The more an employer limits those things that create this sense of purpose, the less likely employees will stay at their positions.”

In this essay, Turner looks at how employees seek value in the workplace. This essay dives into how, as humans, we all need a purpose. If we can find purpose in our work, our overall happiness increases. So, a value and purpose-driven job role can create a positive and fruitful work environment for both workers and employers.

In this essay, talk about how you envision yourself as a professional in the future. You can be as creative as to describe your workplace, your position, and your colleagues’ perception of you. Next, explain why this is the line of work you dream of and what you can contribute to society through this work. Finally, add what learning programs you’ve signed up for to prepare your skills for your dream job. For more, check out our list of simple essays topics for intermediate writers .

For your essay, look deeply into how your school prepares the young generation to be competitive in the future workforce. If you want to go the extra mile, you can interview students who have graduated from your school and are now professionals. Ask them about the programs or practices in your school that they believe have helped mold them better at their current jobs.

In a workplace where colleagues compete against each other, leaders could find it challenging to cultivate a sense of cooperation and teamwork. So, find out what creative activities companies can undertake to encourage teamwork across teams and divisions. For example, regular team-building activities help strengthen professional bonds while assisting workers to recharge their minds.

Finding a job after receiving your undergraduate diploma can be full of stress, pressure, and hard work. Write an essay that handholds graduate students in drafting their resumes and preparing for an interview. You may also recommend the top job market platforms that match them with their dream work. You may also ask recruitment experts for tips on how graduates can make a positive impression in job interviews.

Creating a fun and happy workplace may seem impossible. But there has been a flurry of efforts in the corporate world to keep workers happy. Why? To make them more productive. So, for your essay, gather research on what practices companies and policy-makers should adopt to help workers find meaning in their jobs. For example, how often should salary increases occur? You may also focus on what drives people to quit jobs that raise money. If it’s not the financial package that makes them satisfied, what does? Discuss these questions with your readers for a compelling essay.

Motivation could scale up workers’ productivity, efficiency, and ambition for higher positions and a longer tenure in your company. Knowing which method of motivation best suits your employees requires direct managers to know their people and find their potential source of intrinsic motivation. For example, managers should be able to tell whether employees are having difficulties with their tasks to the point of discouragement or find the task too easy to boredom.

A handful of managers have been worried about working from home for fears of lowering productivity and discouraging collaborative work. Meanwhile, those who embrace work-from-home arrangements are beginning to see the greater value and benefits of giving employees greater flexibility on when and where to work. So first, draw up the pros and cons of working from home. You can also interview professionals working or currently working at home. Finally, provide a conclusion on whether working from home can harm work output or boost it.

Identifying critical skills at work could depend on the work applied. However, there are inherent values and behavioral competencies that recruiters demand highly from employees. List the top five qualities a professional should possess to contribute significantly to the workplace. For example, being proactive is a valuable skill because workers have the initiative to produce without waiting for the boss to prod them.

If you need help with grammar, our guide to grammar and syntax is a good start to learning more. We also recommend taking the time to improve the readability score of your essays before publishing or submitting them.

Meet Rachael, the editor at Become a Writer Today. With years of experience in the field, she is passionate about language and dedicated to producing high-quality content that engages and informs readers. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her exploring the great outdoors, finding inspiration for her next project.

View all posts

The Future of Work Should Mean Working Less

By Jonathan Malesic Sept. 23, 2021

- Share full article

Mr. Malesic is a writer and a former academic, sushi chef and parking lot attendant who holds a Ph.D. in religious studies. He is the author of the forthcoming book “ The End of Burnout ,” from which this essay is adapted.

A dozen years ago, my friend Patricia Nordeen was an ambitious academic, teaching at the University of Chicago and speaking at conferences across the country. “Being a political theorist was my entire adult identity,” she told me recently. Her work determined where she lived and who her friends were. She loved it. Her life, from classes to research to hours spent in campus cafes, felt like one long, fascinating conversation about human nature and government.

But then she started getting very sick. She needed spinal fusion surgeries. She had daily migraines. It became impossible to continue her career. She went on disability and moved in with relatives. For three years she had frequent bouts of paralysis. She was eventually diagnosed with a subtype of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, a group of hereditary disorders that weaken collagen, a component of many sorts of tissue.

“I’ve had to evaluate my core values,” she said, and find a new identity and community without the work she loved. Chronic pain made it hard to write, sometimes even to read. She started drawing, painting and making collages, posting the art on Instagram. She made friends there and began collaborations with them, like a 100-day series of sketchbook pages — abstract watercolors, collages, flower studies — she exchanged with another artist. A project like this allows her to exercise her curiosity. It also “gives me a sense of validation, like I’m part of society,” she said.

Art does not give Patricia the total satisfaction academia did. It doesn’t order her whole life. But for that reason, I see in it an important effort, one every one of us will have to make sooner or later: an effort to prove, to herself and others, that we exist to do more than just work.

We need that truth now, when millions are returning to in-person work after nearly two years of mass unemployment and working from home. The conventional approach to work — from the sanctity of the 40-hour week to the ideal of upward mobility — led us to widespread dissatisfaction and seemingly ubiquitous burnout even before the pandemic. Now, the moral structure of work is up for grabs. And with labor-friendly economic conditions, workers have little to lose by making creative demands on employers. We now have space to reimagine how work fits into a good life.

As it is, work sits at the heart of Americans’ vision of human flourishing. It’s much more than how we earn a living. It’s how we earn dignity: the right to count in society and enjoy its benefits. It’s how we prove our moral character. And it’s where we seek meaning and purpose, which many of us interpret in spiritual terms.

Political, religious and business leaders have promoted this vision for centuries, from Capt. John Smith’s decree that slackers would be banished from the Jamestown settlement to Silicon Valley gurus’ touting work as a transcendent activity . Work is our highest good; “do your job,” our supreme moral mandate.

But work often doesn’t live up to these ideals. In our dissent from this vision and our creation of a better one, we ought to begin with the idea that each one of us has dignity whether we work or not. Your job, or lack of one, doesn’t define your human worth.

This view is simple yet radical. It justifies a universal basic income and rights to housing and health care. It justifies a living wage. It also allows us to see not just unemployment but retirement, disability and caregiving as normal, legitimate ways to live.

When American politicians talk about the dignity of work, like when they argue that welfare recipients must be employed, they usually mean you count only if you work for pay.

The pandemic revealed just how false this notion is. Millions lost their jobs overnight. They didn’t lose their dignity. Congress acknowledged this fact, offering unprecedented jobless benefits: for some, a living wage without having to work.

The idea that all people have dignity before they ever work, or if they never do, has been central to Catholic social teaching for at least 130 years. In that time, popes have argued that jobs ought to fit the capacities of the people who hold them, not the productivity metrics of their employers. Writing in 1891, Pope Leo XIII argued that working conditions, including hours, should be adapted to “the health and strength of the workman.”

Leo mentioned miners as deserving “shorter hours in proportion as their labor is more severe and trying to health.” Today, we might say the same about nurses, or any worker whose ordinary limitations — whether a bad back or a mental health condition — makes an intense eight-hour shift too much to bear. Patricia Nordeen would like to teach again one day, but given her health at the moment, full-time work seems out of the question.

Because each of us is both dignified and fragile, our new vision should prioritize compassion for workers, in light of work’s power to deform their bodies, minds and souls. As Eyal Press argues in his new book, “ Dirty Work ,” people who work in prisons, slaughterhouses and oil fields often suffer moral injury, including post-traumatic stress disorder, on the job. This reality challenges the notion that all work builds character.

Wage labor can harm us in subtle and insidious ways, too. The American ideal of a good life earned through work is “disciplinary,” according to the Marxist feminist political philosopher Kathi Weeks, a professor at Duke and often-cited critic of the modern work ethic. “It constructs docile subjects,” she wrote in her 2011 book, “ The Problem With Work .” Day to day, that means we feel pressure to become the people our bosses, colleagues, clients and customers want us to be. When that pressure conflicts with our human needs and well-being, we can fall into burnout and despair.

To limit work’s negative moral effects on people, we should set harder limits on working hours. Dr. Weeks calls for a six-hour work day with no pay reduction. And we who demand labor from others ought to expect a bit less of people whose jobs grind them down.

In recent years, the public has become more aware of conditions in warehouses and the gig economy. Yet we have relied on inventory pickers and delivery drivers ever more during the pandemic. Maybe compassion can lead us to realize we don’t need instant delivery of everything and that workers bear the often-invisible cost of our cheap meat and oil.

The vision of less work must also encompass more leisure. For a time the pandemic took away countless activities, from dinner parties and concerts to in-person civic meetings and religious worship. Once they can be enjoyed safely, we ought to reclaim them as what life is primarily about, where we are fully ourselves and aspire to transcendence.

Leisure is what we do for its own sake. It serves no higher end. Patricia said that making art is often “meditative” for her. “If I’m trying to draw a plant, I’m really looking at the plant,” she said. “I’m noticing all the different shades of color that maybe I wouldn’t have noticed if I wasn’t drawing it.” Her absorption in the task — the feel of the pen on paper — “puts the pain out of focus.”

It’s true that people often find their jobs meaningful, as Patricia did in her academic career or as I did while working on this essay. But for decades, business leaders have taken this obvious truth too far, preaching that we’ll find the purpose of our lives at work. It’s a convenient narrative for employers, but look at what we actually do all day: For too many of us, if we aren’t breaking our bodies, then we’re drowning in trivial email. This is not the purpose of a human life.

And for those of us fortunate enough to have jobs that consistently provide us with meaning, Patricia’s story is a reminder that we may not always have that kind of work. Anything from a sudden health issue to the natural effects of aging to changing economic conditions can leave us unemployed.

So we should look for purpose beyond our jobs and then fill work in around it. We each have limitless potential, a unique “genius,” as Henry David Thoreau called it. He believed that excessive toil had stunted the spiritual growth of the men who laid the railroad near Walden Pond, where he lived from 1845 to 1847. He saw the pride they took in their work but wrote, “I wish, as you are brothers of mine, that you could have spent your time better than digging in this dirt.”

Pursuing our genius, whether in art or conversation or sparring at a jiujitsu gym, will awaken us to “a higher life than we fell asleep from,” Thoreau wrote. It isn’t the sort of leisure, like culinary tourism, that heaps more labor on others. It is leisure that allows us to escape the normal passage of time without traveling a mile. The mornings Thoreau spent standing in his cabin doorway, “rapt in a revery,” he wrote, “were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance.” Compared with that, he thought, labor was time wasted.

Dignity, compassion, leisure: These are pillars of a more humane ethos, one that acknowledges that work is essential to a functioning society but often hinders individual workers’ flourishing. This ethos would certainly benefit Patricia Nordeen and might allow students to benefit from her teaching ability. In practice, this new vision should inspire us to implement universal basic income and a higher minimum wage, shorter shifts for many workers and a shorter workweek for all at full pay. Together, these pillars and policies would keep work in its place, as merely a support for people to spend their time nurturing their greatest talents — or simply being at ease with those they love.

It’s a vision we can approach from multiple directions, befitting America’s intellectual diversity. Pope Leo, Dr. Weeks and Thoreau criticized industrial society from the disparate, often incompatible traditions of Catholicism, Marxist feminism and Transcendentalism. But they agreed that we need to see inherent value in each person and to keep work in check so everyone can attain higher goods.

These thinkers are hardly alone. We might equally take inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois’s contention that Black Americans would gain political rights through intellectual cultivation and not only relentless labor, or Abraham Joshua Heschel’s view that the Sabbath day of rest “is not an interlude but the climax of living,” or the “ right not to work ” advocated by the disabled artist and writer Sunaura Taylor.

The point is to subordinate work to life. “A life is what each of us needs to get,” wrote Dr. Weeks, and you can’t get one without freedom from work’s domination. “That said,” she continues, “one cannot get something as big as a life on one’s own.”

That means we need one more pillar: solidarity, a recognition that your good and mine are linked. Each of us, when we interact with people doing their jobs, has the power to make their lives miserable. If I’m overworked, I’m likely to overburden you. But the reverse is also true: Your compassion can evoke mine.

Early in the pandemic, we exhibited the virtues we need to realize this vision. Public health compelled us to set limits on many people’s work and provide for those who lost their jobs. We showed — imperfectly — that we could make human well-being more important than productivity. We had solidarity with one another and with the doctors and nurses who battled the disease on the front lines. We limited our trips to the grocery store. We tried to “flatten the curve.”

When the pandemic subsides but work’s threat to our thriving does not, we can practice those virtues again.

Advertisement

Five key trends shaping the new world of work

Job seekers in companies in regions most affected by high unemployment rates must broaden their horizons beyond a search for employment opportunities to exploring work opportunities. Image: Alex Kotliarskyi for Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Segun Ogunwale

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of work.

Listen to the article

- There is transformation happening in the world of work, both as a result of the pandemic, and underlying structural shifts.

- Companies are restructuring for efficiency, and recruiting for skills rather than potential, while talent is highly mobile.

- Digital skills are increasingly central to workers' employability.

From the phenomenon of " quiet quitting " to the great resignation , the post-pandemic reluctance of workers to return for the office has been well documented . There are other changes happening as a result of the subsequent economic slowdown: employment offers have been rescinded amidst layoffs in technology companies often seen as beacons of growth, and a STEM skills shortage has led to calls for upskilling and re-skilling programmes in the workplace and a global scramble for talent . But many of the trends we are currently seeing in the world of work predate the COVID-19 pandemic. Here are five shifts that look set to endure:

1. Restructuring companies for efficiency

Changes to industry structures and disruptions to business models have encouraged companies to restructure for relevance and competitiveness. Companies such as General Electric have split while others have responded with mergers, as in the case of Tata Group . Holding companies that have been able to do without job cuts, like Alphabet, are calling for an increase in employee productivity .

Have you read?

Hybrid entrepreneurship - 5 reasons to build a venture while still working , what is the optimal balance between in-person and remote working, a new study shows just how beneficial remote working can be.

Despite capital flow to many emerging markets, several industries remain informal, fragmented, and dominated by Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) , which create 7 out of 10 jobs. Irrespective of the market, industry and approach, the pursuit of efficiency in companies prioritise retention and hiring of employees with skills and competencies that contribute directly to the bottom line.

2. A shift to skills-based hiring

Faced with the need to deliver short to medium-term results, companies are increasingly hiring for skills backed with experience, and less for potential. This has led to a decline in graduate recruitment . Many employers are eliminating degrees from their hiring criteria in favour of skills assessment. Only 11% of business leaders “strongly agree” that students are graduating from higher education with the necessary competencies. This has led to calls for higher education reform .

Young people entering the world of work have to embrace work-integrated learning opportunities available as internships, placements, and apprenticeship programmes to provide relevant experience in developing their skills. More than four in five employers believe internships can prepare graduates to succeed in their companies.

3. The mobility of talent

The global war for skilled talent has led to massive opportunities for some workers to move across jobs, industries and countries. The normalization of remote work accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and powered by digital technologies for collaboration has made it possible for top talent to glide across jobs or be in multiple jobs at a time. Research predicts that today’s youngest workers will hold twelve to fifteen jobs in their lifetime .

Therefore, individuals and companies must evaluate their work opportunities from a broader and global lens, shifting to a mindset of career mobility and the development of transferable skills for a lifetime of numerous job opportunities. At the same time, the future looks likely to hold higher trade tariffs and tighter border controls, and we have yet to see what this means for worker mobility.

4. The rise of 'work' and the decline of 'employment'

The rise of platform companies has fundamentally changed the rules of employment . Companies such as Uber have created work opportunities for around 5 million drivers worldwide without signing a single driver employment contract. The gig economy has opened up opportunities for individuals and companies to access a diverse and global pool of talents to get tasks done on demand - as well as undermining many of the structures that have underpinned employment security.

This has changed how organizations approach recruitment, with a move away from human resources departments managing employees, and towards talent strategy teams exploring how to meet human resources needs. Analytic tools to measure performance enable a holistic view of talent management in the workplace. Job seekers in companies in regions most affected by high unemployment rates must broaden their horizons beyond a search for employment opportunities to exploring work opportunities. Regulators in industries dominated by platform companies need to push for benefits to be tied to work opportunities, not just employment, to protect the interest of workers.

5. The central importance of digital skills

The digital transformation of industries has brought about massive shifts in the world of work. Organizations across all sectors, from agribusiness, finance and manufacturing to media, are evolving into technology companies . In this context, 'employability' is not just about 'soft skills' such as communication, collaboration, critical thinking and emotional intelligence. As digital platforms in AI applications, robotics, and the Internet of Things make inroads into the workplace, employability skills will be increasingly centred around using these digital technologies at work.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Jobs and the Future of Work .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Age diversity will define the workforce of the future. Here’s why

Susan Taylor Martin

May 8, 2024

From start-ups to digital jobs: Here’s what global leaders think will drive maximum job creation

Simon Torkington

May 1, 2024

70% of workers are at risk of climate-related health hazards, says the ILO

Johnny Wood

International Workers' Day: 3 ways trade unions are driving social progress

Giannis Moschos

Policy tools for better labour outcomes

Maria Mexi and Mekhla Jha

April 30, 2024

How to realize the potential of rising digital jobs

Stéphanie Bertrand and Audrey Brauchli

April 29, 2024

Ethics and the Future of Meaningful Work: Introduction to the Special Issue

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2023

- Volume 185 , pages 713–723, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Evgenia I. Lysova 1 ,

- Jennifer Tosti-Kharas 2 na1 ,

- Christopher Michaelson 3 ,

- Luke Fletcher 4 ,

- Catherine Bailey 5 &

- Peter McGhee 6

7283 Accesses

5 Citations

38 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The world of work over the past 3 years has been characterized by a great reset due to the COVID-19 pandemic, giving an even more central role to scholarly discussions of ethics and the future of work. Such discussions have the potential to inform whether, when, and which work is viewed and experienced as meaningful. Yet, thus far, debates concerning ethics, meaningful work, and the future of work have largely pursued separate trajectories. Not only is bridging these research spheres important for the advancement of meaningful work as a field of study but doing so can potentially inform the organizations and societies of the future. In proposing this Special Issue, we were inspired to address these intersections, and we are grateful to have this platform for advancing an integrative conversation, together with the authors of the seven selected scholarly contributions. Each article in this issue takes a unique approach to addressing these topics, with some emphasizing ethics while others focus on the future aspects of meaningful work. Taken together, the papers indicate future research directions with regard to: (a) the meaning of meaningful work, (b) the future of meaningful work, and (c) how we can study the ethics of meaningful work in the future. We hope these insights will spark further relevant scholarly and practitioner conversations.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Normative Meaning of Meaningful Work

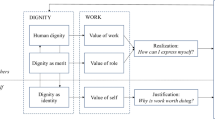

Examining the Role of Dignity in the Experience of Meaningfulness: a Process-Relational View on Meaningful Work

What makes work meaningful.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: The Future Is Now

When we initially proposed the Special Issue topic, “Ethics and the Future of Meaningful Work,” to the Journal of Business Ethics in 2019, we were contemplating advances in, for example: the technological conditions of work (e.g., automation, artificial intelligence), the workplace environment (e.g., worker mobility; co-working arrangements; increasing insecurity and work intensity), workplace demographics (e.g., differences related to age, career stage, and life-stage; gender contrasts; and efforts around diversity, equity, and inclusion), and geographical shifts (e.g., economic power rebalancing and increasing urbanization). Each of these factors has unique implications for transforming the world of work and therefore the meaningful connection people have to that work and its associated ethical implications. For example, when people’s work becomes automated, do they lose a link to what made that work meaningful, or are they freed up to pursue more meaningful work? What is the moral responsibility of organizations to enable the pursuit of meaningfulness in the workplaces of the future?

At that time, we could not have known that a global pandemic was approaching that would radically upend almost overnight how, where, when, and—most crucially what work means— why we work. Two international conferences that we had designated as opportunities to “workshop” potential submissions to the special issue were postponed and replaced by one global question-and-answer Zoom call. The strong levels of interest we witnessed in participating in the online forum demonstrated that scholarship on meaningful work was undeterred by the pandemic, but it also showed us that there is no replacement for face-to-face conferences to support meaningful, sustained interactions.

While many people, including us, were theoretically contemplating the implications of robots coming to take our jobs in an unknown, ambiguous, and uncertain “future of work,” a low-tech, old-style public health threat disrupted our present. The COVID-19 pandemic tragically claimed the lives of many people, including some family members and friends of (potential) contributors to and editors of the special issue. For survivors, it transformed—in both temporary and permanent ways—the world of work. The ensuing upheaval—including the designation of some workers as “essential”, increasing numbers of people working from home, and the so-called “Great Resignation” with the ensuing labor shortage—all have deep implications for employees, organizations, and even societies in terms of what work is offered, pursued, and further developed (e.g., Akkermans et al., 2020 ; Cook, 2021 ; Malhotra, 2021 ). The continuing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic further complicate our ability to experience, sustain, and provide meaningful work (e.g., Kramer & Kramer, 2020 ). Of course, the pandemic was not playing out in isolation. Other global issues—from political polarization, racial unrest, and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, to the rapidly-advancing changes to the climate—compounded the instability of our economic, social, and governmental systems. Such macro-level turbulence and political unrest also makes people question their own sense of meaning and purpose, and creates a more uncertain future in which to understand and embed meaningful work (Fletcher & Schofield, 2021 ; Michaelson & Tosti-Kharas, 2020 ). The lesson, we believe—in addition to requiring us to stay nimble in our research, just as we have had to in our work lives these past several years—is that questions addressing the intersection of meaningful work, ethics, and the future of work, writ large, will become ever-more important as we collectively navigate a complex environment.

Even prior to the events of the last several years, research on meaningful work was on the rise. We witnessed a “Do what you love” cultural zeitgeist, as well as its ensuing backlash –which explored, for example, the ways in which the love employees feel for their work could be co-opted by organizations seeking to profit from and exploit this love (e.g., Cech, 2021 ; Jaffe, 2021 ; Tokumitsu, 2015 ). Management researchers also spent a great deal of time researching and cataloging what it means to view work as meaningful, including conceptualizations of work as a calling, passion, or purpose. Within the past few years, researchers have published several literature reviews (Bailey et al., 2019b ; Blustein et al., 2023 ; Laaser & Karlsson, 2022 ; Lysova et al., 2019a ; Thompson & Bunderson, 2019 ) and meta-analyses (Allan et al., 2019a , 2019b ; Dobrow et al., 2023 ), an edited handbook (Yeoman et al., 2019 ), and three journal special issues (Bailey et al., 2019a ; Laaser, 2022 ; Lysova et al., 2019b ) on these topics, illustrating growing scholarly attention. Meaningful work was also the inspiration for the theme of the 2016 Academy of Management conference in Anaheim, which aimed to foster conversations about “Making Organizations Meaningful.” These developments signal not only increasing interest in the concept of meaningful work but also raise several significant and as yet unanswered ethical questions that would benefit from interdisciplinary attention.

By joining the dialogue between ethics and organization studies about meaningful work (e.g., Michaelson et al., 2014 ) with the ever-present reality of future trends in working, this Special Issue addresses a topic of wide-ranging interest and applicability. The papers in this Special Issue demonstrate that meaningful work is not only a managerial imperative to attract and retain future workers. It is also potentially a moral imperative of individuals to pursue a positive impact through their work; of organizations to provide work that serves a worthwhile purpose; and of societies to protect activities, including work, that give shape and significance to our lives. Before we turn to an overview of the Special Issue, the papers it includes, and the themes that it covers, we briefly review the existing literature on meaningful work, business ethics, and the future of work.

What Do We Know About the Intersection of Meaningful Work, Business Ethics, and the Future of Work?

Business ethics is a discipline, meaningful work is a construct, and the future of work is a research setting or context. In theory, this means that they should be able to inform each other and do so without redundancy. Moreover, the future of work provides a kind of “extreme” research setting (Bamberger & Pratt, 2010 ) in which issues surrounding the ethics of meaningful work—from who has a right to it, to who has a duty to provide it, to what it means when meaningless work prevails—are heightened. There have been very few studies to date that truly speak to the intersection of these three topics–notable exceptions include Bowie, 2019 ; Kim & Scheller-Wolf, 2019 ; Smids et al., 2020 ; Turja et al., 2022 . Therefore, we start by discussing prior research at the nexus between each of the pairs of topics in order to see what important questions remain to be addressed.

Meaningful Work and Business Ethics

Although scholars rarely agree on a precise definition of meaningful work (Bailey et al., 2019b ), the term generally refers to work that is personally and/or socially significant and worthwhile (Lysova et al., 2019a ; Pratt & Ashforth, 2003 ). Part of the disagreement on the definition is due to the sheer number of disciplinary approaches and perspectives that have been used to study meaningful work (Bailey et al., 2019b ). Historically, social scientists (more specifically, organizational psychologists) and philosophers (more specifically, business ethicists) have each studied meaningful work without a full awareness of each other’s perspectives (Michaelson et al., 2014 ). The former group has studied meaningful work as an individually fulfilling aspiration that has “positive valence” (Rosso et al., 2010 , p. 95), clarifies one’s identity in terms of what one does and where one belongs (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003 ), and enables self-actualization and the sense that one’s work is worthy (Lepisto & Pratt, 2017 ). The latter have studied it as, among other things, a human right (e.g., Bowie, 1998 ; Schwartz, 1982 ), a virtue (e.g., Beadle & Knight, 2012 ), and a “fundamental human need” (e.g., Yeoman, 2014 , p. 235). Meaningful work in organization studies has tended to draw primarily from the social scientific perspective to be framed in terms of an individual’s aspiration or motivation to perform meaningful work or an organization’s potential to perform better by providing opportunities for their employees to experience meaningful work (e.g., Bailey et al., 2019b ; Lysova et al., 2019a ). In business ethics, however, the focus has been more on the philosophical side, specifically on the responsibility of organizations or the state to foster a work environment in which the prevailing conditions preserve an individual’s autonomy to choose meaningful work (Michaelson, 2021 ; Michaelson et al., 2014 ). Of course, these perspectives are not mutually exclusive, and an interdisciplinary viewpoint opens up the possibility that responsible employers can serve individual employees’ preferences (e.g., Gifford & Bailey, 2018 ).

Meanwhile, an additional strand of social scientific research that explores work orientation, and particularly work as a calling—work that a person views as morally, personally, and socially significant and the end in itself (Wrzesniewski, 2012 ). However, there is extensive debate among both social scientists (e.g., Thompson & Bunderson, 2019 ; Dik & Shimizu, 2019 ) and philosophers (e.g., Care, 1984 ) about whether meaningful work that is a calling must focus on “serving self or serving others” (Michaelson & Tosti-Kharas, 2019 , p. 19). Although philosophers have long debated whether meaningfulness is a subjective phenomenon, determined by the individual, or an objective phenomenon with clear references to moral conditions in which work is performed (e.g., Wolf, 2010 ). At the same time, meaningful work scholars have considered the well-being of others as a dimension of what makes work meaningful (e.g., Lips-Wiersma & Morris, 2009 ; Rosso et al., 2010 ). Yet, with a few exceptions, scholarship has rarely asked whether meaningful work must be good for others beyond ourselves (e.g., Michaelson, 2021 ; Veltman, 2016 ). The connection between meaningful work and business ethics has been also reflected in the growing research that explores how the experience of meaningful work is enabled by ethical and responsible leadership (e.g., Demitras et al., 2017 ; Wang & Xu, 2019 ; Lips-Wiersma et al., 2020 ) and corporate social responsibility (e.g., Aguinis & Glavas, 2019 ; Brieger et al., 2020 ; Janssen et al., 2022 ).

Meaningful Work and the Future of Work

As of this writing, a Google Scholar search of the phrase “future of work” yielded nearly 90,000 results, about one-third of which were published within the past 5 years, and a regular Google search turned up 134 million hits. This observation clearly points to the recent exponential growth of interest in this topic. From the perspective of meaningful work, the future of work research tends to focus on whether job loss created by shifts like artificial intelligence and automation will pose a threat or opportunity to the quality of our work and lives, and more specifically to the pursuit of meaningful work. On the one hand, if jobs that are routine and potentially meaningless are automated, people could be freed up to pursue meaningful endeavors elsewhere, in their work and/or lives outside of work (e.g., Smids et al., 2020 ). This version of reality seems closest to the prediction by John Maynard Keynes nearly a century ago when he coined the term “technological unemployment” ( 1930 /2010). As scholars, we should be careful about judging which jobs could be automated with little worker pushback in view of the highly personal experience of work as meaningful. A poignant example is a long-haul truck driver interviewed in the documentary, The Future of Work and Death (Blacknell & Walsh, 2016 ) who, when asked what his plans are should self-driving trucks render him redundant, replies, “I’m going to retire when I die in the truck.” Truck driving reported the second-highest rate of on-the-job deaths in 2020 according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics ( 2020 ); however, this example suggests that there are real tradeoffs between subjective and normative perspectives on what work should be automated. In other words, should certain jobs be saved to satisfy the subjective preferences of those who want to perform them, should the market decide, or should the state paternalistically prescribe which jobs are worth saving?

When we refer to the future of work, we should also be careful not to limit our understanding to only the implications of technological unemployment, specifically the headline-catching notion of sentient robots or machines taking over individual jobs. Recent reviews of the future of work identify several dimensions, including technological, social/demographic, economic, and political/institutional (Balliester & Elsheikhi, 2018 ; Santana & Cobo, 2020 ). Within this framework, automation and AI represent only one sub-category within the technological dimension, which also includes the emergence of new forms of work (e.g., gig work, platform work, telework), digitalization, and innovation. Indeed, there has been some relevant research that focused on studying experiences of meaningful work in new forms of employment like the gig economy (e.g., Kost et al., 2018 ; Nemkova et al., 2019 ; Wong et al., 2020 ).

The social/demographic dimension of the future of work includes issues affecting individual workers, such as burnout, work-nonwork conflict; attention to broader societal imperatives including corporate social responsibility; and issues affecting vulnerable workers, such as immigrants, minorities, and older workers. Here, research has addressed how workers respond to challenges to maintaining meaningful work, including the burnout and overwork that accompany the connection to broader social imperatives like animal welfare (Bunderson & Thompson, 2009 ; Schabram & Maitlis, 2017 ) or volunteer work (e.g., Toraldo et al., 2019 ). Some emerging research has started to explore how different groups, such as those in blue-collar work or from minoritized groups, may have restricted opportunities to access some forms of meaningful work (e.g., Allan et al., 2019a , 2019b ; Lips-Wiersma et al., 2016 ).

The other two dimensions are the economic , which considers wage inequality, (un)employment, and job precarity, and the political/institutional , which considers industrial relations, trade unions, and the labor market. These future of work dimensions are addressed in sociological (e.g., Gallie, 2019 ; Lasser & Karlsson, 2022 ) and vocational research (e.g., Allan et al., 2020 ; Allan et al., 2019a , 2019b ; Duffy et al., 2016 ) on decent work, or the work that provides access to adequate healthcare, protection from physical and psychosocial harm, adequate compensation, adequate rest, and organizational values that complement family and social values. Research that explores decent work as a psychological work experience builds on the assumption that economic constraints and marginalization limit the possibility for individuals to secure decent work, and, therefore, for individuals to experience meaningful work (Allan et al., 2019a , 2019b ; Duffy et al., 2016 ). A review of the literature reveals that research on meaningful work has mostly considered the technological and social/demographic dimensions, viewing them as presenting both future threats and opportunities, but has paid less attention to the economic and political/institutional dimensions.

Business Ethics and the Future of Work

It might be fair to say that any business ethics research that is concerned about employee well-being is focused on making the future of work better than the present. From Adam Smith’s worry that division of labor capitalism made workers “stupid” to Karl Marx’s concerns about the alienation of labor, ethicists and political theorists have tried to envision better workplaces that respect human dignity (e.g., Pirson, 2017 ), support employee participation in workplace governance (e.g., Hsieh, 2005 ), and align with employees’ ethical values (e.g., Paine, 2004 ). Much business ethics research has been mobilized by the role of markets in fostering economic inequality (e.g., Beal & Astakhova, 2017 ), unequal treatment of workers in different jurisdictions (e.g., Donaldson & Dunfee, 1999 ), and structural injustices exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Van Buren & Schrempf-Stirling, 2022 ). Generally, business ethicists have worried more about sweatshop abuse (e.g., Arnold & Bowie, 2003 ), overwork (e.g., Golden, 2009 ), and workaholism (e.g., Boje & Tyler, 2009 ) than they have worried about technological future in which there is no work at all.

More recently, perhaps as robots and artificially intelligent machines have become more of a reality, scholars have begun to fret more about technology, particularly whether life will be “worth living in a world without work” (Danaher, 2017 , p. 41). It is possible that the jobs people lose to technology will be ones that were meaningful to them, making it difficult to move on (e.g., Smids et al., 2020 ; Turja et al., 2022 ). While the foreseeable future probably portends continued concern about familiar ethical challenges at work, the unforeseeable future could possibly bring unfamiliar ethical challenges having more to do with the “axiological challenge” (Kim & Scheller-Wolf, 2019 , p. 320) of how to replace work in a meaningful life. As long as human work remains, however, technology will influence the freedom and autonomy that have the potential to make work worth doing. Already, algorithmic decision-making about human resources (e.g., Leicht-Deobald et al., 2019 ) and the technological monitoring of employee activity (Martin et al., 2019 ) are seen to infringe upon employee autonomy, a potential invasion of the right to privacy as well as a critical element of the experience of meaningful work.

What Are the Insights From This Special Issue?

Our quest in this Special Issue was to seek to research the relatively understudied intersection of all three areas: business ethics, meaningful work, and the future of work. The call for papers ultimately attracted 72 submissions, a strong response in terms of both quantity and quality that we believe further justifies the novelty, timeliness, and resonance of the topic. After several rounds of peer-reviewed revisions, seven papers were finally selected to comprise this Special Issue along with this introductory essay. This Special Issue itself represents a variety of contributions highlighting the diversity of its authors. It features both conceptual and empirical contributions, as well as philosophical and social scientific approaches. Its authors come from universities in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand, the UK, and the US. It also seems important to note, although this was not by design, that its editors come from universities in the Netherlands, New Zealand, the UK, and the US and represent multiple disciplinary approaches, including social science/psychology and philosophy/ethics. Overall, we hoped this Special Issue would be a valuable opportunity to truly bridge these divergent viewpoints to advance this constructive dialogue. Below, we provide a brief overview of each of the papers included in this issue.

First, Sarah Bankins and Paul Formosa (this issue) offer a conceptual article, The ethical implications of artificial intelligence (AI) for meaningful work . The authors note that, since the industrial revolution, technological advancements have always had significant implications for meaningfulness through changes to work, skills, and affective experiences. In the paper, they propose three paths of AI deployment and discuss how, through each of these paths, AI may enhance or diminish five dimensions of meaningful work–task integrity, skill cultivation, and use, autonomy, task significance, and belongingness. The paths they identify are: replacing , in which AI takes on some tasks while workers remain engaged in other work processes; tending the machine , in which AI creates new forms of human work; and amplifying , in which AI assists workers with their tasks and/or enhances their abilities. Bankins and Formosa argue that while some pathways, such as tending the machine, may significantly limit opportunities for meaningful work, AI has the potential to make some types of work more meaningful by undertaking more boring tasks and thereby amplifying human capabilities. The authors offer the caveat that, while some jobs may be affected by just one of these paths, others may experience all three. Bankins and Formosa further draw on the “AI4People” ethical AI framework, which identifies five principles–beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, justice, and explicability–that enable us to assess the ethical implications of AI implementation on meaningful work. In summary, their argument suggests that there is not likely to be one single impact of AI on meaningful work, as it has the potential to make work meaningful for some workers but it can also make work less meaningful for others.

Next, in their article, Saving the world? How CSR practitioners live their calling by constructing different types of purpose in three occupational stages , Enrico Fontana, Sanne Frandsen, and Mette Morsing (this issue) examine one form of deeply meaningful work, work as a calling, to address the question of whether the sense of purpose that underpins a calling changes over time. In particular, they challenge the notion that callings constitute the end point of a journey towards self-actualization and instead draw attention to the tensions experienced by individuals as they seek to pursue their callings within organizational settings whose agendas may be very different from their own. Such tensions may be especially acute for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practitioners who may be driven by altruistic goals that potentially contrast with the realities of organizational life. Through a qualitative investigation of CSR practitioners in Sweden, the authors find that respondents constructed the purpose of their work differently across career stages. Early-career practitioners pursued an activist purpose aimed at affecting transformational change in their company’s approach to CSR, while mid-career practitioners constructed a win–win purpose grounded in the sense that not only did their work tackle social issues but it also supported their employer’s aims. Finally, late-career practitioners adopted a corporate purpose that prioritized corporate success unrelated to social aspirations—their own or their organization’s. This research reveals that callings can be lived out in different ways that may differ from a perception that callings are essentially ethical and prosocial. The authors highlight the potentially harmful long-term effects of companies prioritizing commercial goals over the social aspirations that drive CSR practitioners’ early work orientations.

In Body-centric cycles of meaning deflation and inflation , authors Anica Zeyen and Oana Branzei (this issue) draw on a longitudinal study of 24 self-employed disabled workers in UK organizations to explore how respondents used their bodies to make meaning at work during the COVID-19 global pandemic. In so doing, they employ an “ethics of embodiment” theoretical lens that views meaning-making in the context of work as inherently body-centric. Disabled workers are particularly relevant to study in this context given how marginalized they may be at work precisely because of their bodies, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Utilizing interview and diary data and analyzing it in an abductive fashion, the authors found that disabled workers purposefully enrolled their bodies in what they term dramas of suffering or dramas of thriving . These dramas not only rendered mind–body differences visible to the workers and others at work but also instigated their meaning-making at work: dramas of suffering deflated meaning while dramas of thriving inflated it. The authors developed a process model of meaning-making through body drama that showed this process to be cyclical: suffering demanded more meaning-making, which often entailed more suffering, and so on, with a similar cycle for thriving. Importantly, each respondent was locked into their own body-driven cycle of either suffering or thriving. This study provides a unique perspective on the various forms of worker disability, as well as the various paths disabled workers can take to strengthen or weaken meaningfulness in response to a challenge like the pandemic.

Frank Martela’s (this issue) paper, The normative value of making a positive contribution—Benefiting others as a core dimension of meaningful work , asserts that normative accounts of meaningful work should be expanded to include contributing–doing work that has a positive impact on the lives of other people—as another key moral dimension of meaningful work. While the view that work must make a social contribution may be assumed in some subjective accounts of meaningful work—such as when meaningfulness is associated with corporate social responsibility—it is not always viewed as a normative requirement. Martela reflects on normative accounts of meaningful work that have been built mostly around autonomy, the capability for self-development, and the avoidance of alienation. What makes these accounts normative is that they tend to impose moral responsibilities on employers to provide work that preserves the freedom of the worker to pursue work that is subjectively meaningful. However, while these accounts may be good for the worker, Martela’s account of meaningful work may also impose a normative obligation on the worker to perform work that is good for others . Moreover, this account of meaningful work not only ascribes responsibilities to the individual, but it also implies that the employer is morally responsible for providing work that enables the individual to make a positive contribution to society. Martela argues that doing work that does not make a positive impact or being separated from the positive contribution one’s work is making, is its own form of alienation from work.

David Silver (this issue) echoes this theme in Meaningful work and the purpose of the firm while expanding on what the pursuit of a positive social contribution means for the organization. He argues that it is important to create products and services that provide a benefit to the people who ultimately use them. However, he asserts that doing so is the fundamental goal of the firm, not merely the aim of meaningful work. Silver thus situates his examination of meaningful work in the context of debates about the purpose of the firm, particularly against the backdrop of a profit maximization thesis that has only relatively recently been challenged as a legitimate organizational purpose. Because people typically work within organizations, Silver argues that employees’ opportunity to perform work that is meaningful by virtue of its societal contribution can either be supported or undermined by their employer’s purpose. He proposes that when that purpose is profit maximization alone, even work that makes a positive contribution to others, whether organizational shareholders or other stakeholders, may not feel meaningful. Conversely, when the purpose of the firm is to benefit end users, even work that might otherwise be viewed as meaningless can be imbued with a sense of serving a meaningful purpose.

In his paper, What makes work meaningful? Samuel Mortimer (this issue) acknowledges that meaningful work must be both personally motivating and objectively worth pursuing. He observes that in qualitative interview studies of workers who feel their work is deeply meaningful, they not only describe how the work makes them feel, but also explain how their work contributes to a broader purpose or mission to which they are committed. Mortimer argues that the answer to the question of what makes work meaningful can be found in a burgeoning philosophical consensus that there must be both subjective and objective elements to meaningful work. He argues that subjective, or experiential, accounts of meaningful work are of value to providers of work endeavoring to attract and retain employees but that it is circular to tell someone who is seeking meaningful work to find work that feels meaningful to them. However, Mortimer also recognizes that so-called objective accounts of meaningful work show that such work, which sometimes entails significant sacrifice, can have the unintended consequence of undermining the pursuit of a meaningful life. He aims to integrate these two accounts of meaningful work by arguing that volitional commitment to a particular line of work makes it normatively meaningful.

Santiago Mejia (this issue), in The normative and cultural dimension of meaningful work: Technological unemployment as a cultural threat to a meaningful life , also seeks to expand our understanding of meaningful work beyond the subjective experience of the individual worker. In doing so, he discusses not only what makes work meaningful but also why work matters. Mejia draws attention to the pervasiveness of work in our society, which is evident in the fact that conventional measures of societal well-being include, for example, the unemployment rate, how we identify ourselves with our occupations, and how we measure time in terms of pre-work education, our working life, and post-work retirement. Mejia imagines a future in which we may potentially work less, or not at all, and envisions a cultural crisis in which the absence of work will take away a central organizing telos around which our contemporary lives gravitate—including the opportunity that work provides to contribute to our own and the common good.

What Are the Takeaways and Future Research Directions?

A consideration of the common themes emerging from the Special Issue papers points to three fundamental questions: (a) What is the meaning of meaningful work? (b) What is the future of meaningful work? and (c) How should we study the ethics of meaningful work in the future? We believe attention to these themes and questions would be particularly fruitful moving forward to inform the future of both research and practice on meaningful work, business ethics, and the future of work.

What Is the Meaning of Meaningful Work?

One of the main themes identified in the Special Issue concerns how we conceptualize meaningful work. In fact, the four final papers together grapple with this question, while each author takes a distinct perspective on what “counts” as meaningful work. Martela (this issue) and Silver (this issue) argue that meaningful work must make a societal contribution. Conversely, Mortimer (this issue) and Mejia (this issue) merge the societal, normative view of meaningful work as doing good with the more personal and sociocultural view that meaningful work is volitional (Mortimer) and culturally determined (Mejia). Although the great variety of experiences of meaningful work makes it an endlessly fascinating concept, many philosophical questions remain, including: Is what unites all such experiences the subjective sentiment on the part of the worker that what they are doing is meaningful? Is it possible for them to be objectively mistaken—for the work one thought to be meaningful actually to be quite meaningless? Given that immoral work has been used as a counterexample to challenge meaningful work subjectivism, is it reasonable to suggest that all meaningful work must be moral work?

In sum, there remains room to articulate more clearly what “the search for something more” (Ciulla, 2000 ) in one’s work consists of, whether from the subjective or objective perspective. In their implicit dialogue with one another and with philosophical research on meaningful life (especially Wolf, 2010 ) and meaningful work (including Michaelson, 2021 ; Veltman, 2016 ), these four papers in the Special Issue by Martela, Silver, Mortimer, and Mejia all suggest that while the subjective experience of meaningfulness may be necessary to render work meaningful, it is not sufficient to render work normatively meaningful. In fact, to our knowledge, these papers comprise the most comprehensive, collective attempt to challenge the assumption, shared by many organization scholars and business ethicists, that what makes work meaningful is “in the eye of the beholder” (Michaelson et al., 2014 , p. 86). They challenge this so-called subjectivist account of meaningful work by suggesting that meaningful work ought to be moral work, although some are careful to note that this does not necessarily imply that all normatively moral work is experienced as meaningful work (also see Yeoman, 2014 ).

We note that, in addition to these four papers, dozens more of the submissions we received questioned what meaningful work means. While achieving a consensus would increase continuity and foster a more coherent dialogue, a pluralist conceptualization of meaningful work permits the field to engage with a broader perspective on what constitutes meaningful work. We thus encourage future researchers to continue to conceptually and empirically explore the multiple meanings of meaningful work, similar to the efforts of research on calling (e.g., Dik & Shimizu, 2019 ; Thompson & Bunderson, 2019 ). In any case, scholars should specify upfront in their studies what they mean by meaningful work and why they have chosen this particular perspective. Furthermore, in line with Mejia’s (this issue) suggestion that meaningful work is culturally determined, we also call for cross-cultural research that examines how cultural accounts of what makes work worth doing enable or hinder people’s access to meaningful work. So far, research addressing these important questions remains scarce (cf. Boova et al., 2019 ). Moreover, we encourage scholars to consider how such debates about the meaning of meaningful work could shape whether and how organizations should implement certain organizational policies and practices with the aim of enabling meaningful work.

What Is the Future of Meaningful Work?