- Create new account

- Reset your password

- Translation

- Alternative Standpoint

- HT Parekh Finance Column

- Law and Society

- Strategic Affairs

- Perspectives

- Special Articles

- The Economic Weekly (1949–1965)

- Economic and Political Weekly

- Open Access

- Notes for contributors

- Style Sheet

- Track Your Submission

- Debate Kits

- Discussion Maps

- Interventions

- Research Radio

Advanced Search

A + | A | A -

NEP 2020 and the Language-in-Education Policy in India

The National Education Policy of India 2020 is a significant policy document laying the national-level strategy for the new millennium. It is ambitious and claims universal access to quality education as its key aim, keeping with the Sustainable Development Goal 4 of the United Nations Agenda 2030. One of the highlights of the NEP is its emphasis on mother tongue education at the primary levels in both state- and privately owned schools. The present paper critically assesses the NEP 2020, primarily in relation to the language-in-education policy. The paper argues that it presents a “contradiction of intentions,” aspiring towards inclusion of the historically disadvantaged and marginalised groups on the one hand, while practising a policy of aggressive privatisation and disinvestment in public education on the other.

The author is thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the earlier draft that helped sharpen her arguments. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the public lecture organised by the students of the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2019, and the author is grateful to them for giving her the opportunity to talk on this subject. The usual disclaimer applies.

The National Education Policy of India (NEP) 2020 is a landmark policy document being the first education policy to be drafted in the new millennium. The last NEP was formulated in 1986. Some amendments were added in 1992. It is a significant public policy instrument for India, a country that is proud of its large youth population. It provides the ground on which the education structure, objective, and the future of the young minds of India is to be built. The government has remarked that the new education policy marks a notable shift from what to think to how to think in the digital age (Bhasin 2020). Claiming that the NEP lays foundation for a new India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi opined that it will promote imagination by moving away from herd mentality (Express News Service 2020). The new policy underlines the need for online and digital platforms in teachinglearning and stresses multidisciplinary and forward-looking vision with a light but tight approach under a single centralised regulator, that is, the National Higher Education Commission1 (NEP 2020).

The draft NEP 2019 and NEP 2020 have attracted many scholars who have highlighted various segments of the policy and presented critical appraisal (Agnihotri 2020; Jha and Parvati 2020). However, there seems to be a dearth of a critical discourse on the question of language policy and mother tongue education in the NEP 2020 within the paradigm of social sciences, especially the realm of political studies. Language policy and language-in-education remains mostly discussed by linguists and educationists and not considered seriously within political science. This paper marks a shift by arguing that language is very much a political question and education policy has long-term political-social ramifications. The choice of language is equally a matter of power dynamics in society. From defining what constitutes a language to whether it is incorporated or ignored by school and university curricula is a matter of choice. This further raises the question as to who chooses and whose choice becomes paramount? What about the future of minority language speakers? In this respect, the paper critically analyses the aspects of NEP, such as the recommendation of establishing special education zones (SEZs), recruitment of teachers, the rigour towards privatisation, and the issue of social justice. It concludes that the NEP 2020 in its present form exhibits a contention of intention. Especially at a time when the studentteacher ratios have gone awry with reports on severe shortage of teachers and faculties in higher education institutions, the rollback of public funding for education when India has fallen back in the progress it made in poverty reduction between 2006 and 2016 (Press Trust of India 2020). It is estimated that during the pre-COVID-19 period, about 35% of the rural population was poor and this can grow to 50%55% in rural areas and 30%35% in urban regions. This adversely impacts the poor and marginalised, especially the people belonging to the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) communities (Ram and Yadav 2021). Education is a major path to bring in positive economic development and improve the dipping graph of employment in India.

Dear Reader,

To continue reading, become a subscriber.

Explore our attractive subscription offers.

To gain instant access to this article (download).

(Readers in India)

(Readers outside India)

Your Support will ensure EPW’s financial viability and sustainability.

The EPW produces independent and public-spirited scholarship and analyses of contemporary affairs every week. EPW is one of the few publications that keep alive the spirit of intellectual inquiry in the Indian media.

Often described as a publication with a “social conscience,” EPW has never shied away from taking strong editorial positions. Our publication is free from political pressure, or commercial interests. Our editorial independence is our pride.

We rely on your support to continue the endeavour of highlighting the challenges faced by the disadvantaged, writings from the margins, and scholarship on the most pertinent issues that concern contemporary Indian society.

Every contribution is valuable for our future.

- About Engage

- For Contributors

- About Open Access

- Opportunities

Term & Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Circulation

- Refund and Cancellation

- User Registration

- Delivery Policy

Advertisement

- Why Advertise in EPW?

- Advertisement Tariffs

Connect with us

320-322, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai, India 400 013

Phone: +91-22-40638282 | Email: Editorial - [email protected] | Subscription - [email protected] | Advertisement - [email protected]

Designed, developed and maintained by Yodasoft Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Multilingualism in india.

With a growing population of just over 1.3 billion people, India is an incredibly diverse country in many ways. This article will focus specifically on contemporary linguistic diversity in India, first with an overview of India as a multilingual country just before and after Independence in 1947 and then through a brief outline of impacts of multilingualism on business and schools, as well as digital, visual, and print media.

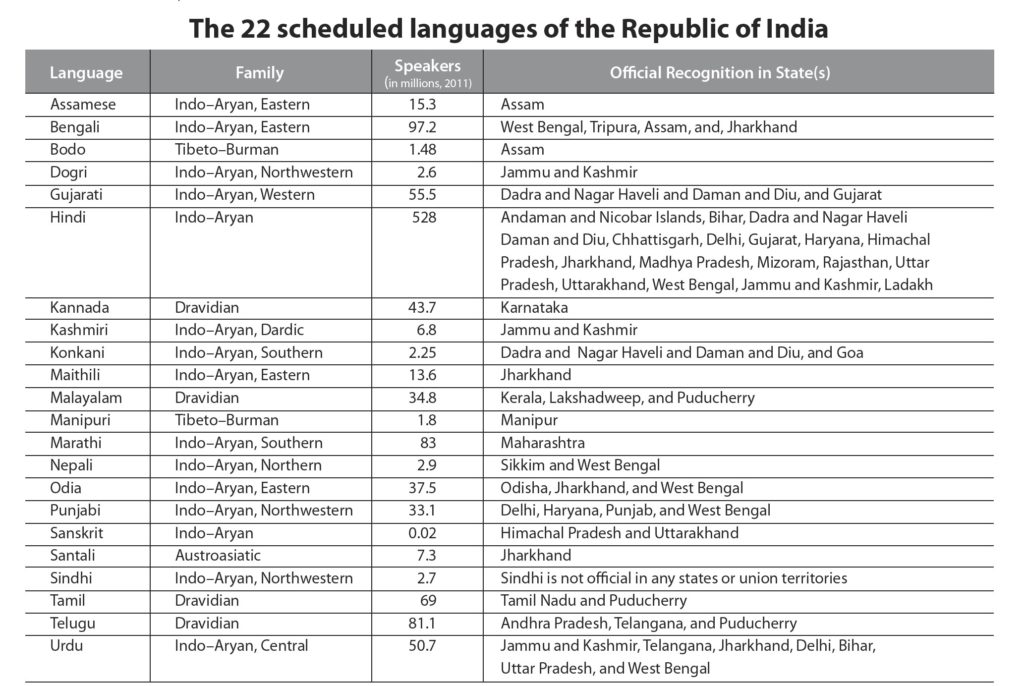

India is home to many native languages, and it is also common that people speak and understand more than one language or dialect, which can entail the use of different scripts as well. India’s 2011 census documents that 121 languages are spoken as mother tongues, which is defined as the first language a person learns and uses.1 Of these languages, the Constitution of India recognizes twenty-two of them as official or “scheduled” languages. Articles 344(1) and 351 of the Constitution of India, titled the Eighth Schedule, recognizes the following languages as official languages of states of India: Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu.2

Six languages also hold the title of classical languages (Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil, and Telugu), which are determined to have a history of recorded use for more than 1,500 years and a rich body of literature. Furthermore, for a contemporary language to also be a classical language, it must be an original language and cannot be a variety, such as a dialect, stemming from another language. Just as there are many people who wish for their mother tongues to be recognized as official, scheduled languages, there are also efforts to add Indian languages to the list of classical languages. Once a language has the official status of a classical language, the Ministry of Education organizes international awards for scholars of those languages, sets up language studies centers, and grants funding to universities to promote the study of the language. Interestingly, the Constitution of India lists no national language for the country as a whole.

Of the official, scheduled languages, Modern Standard Hindi—as an umbrella term for a family of languages—has the most mother tongue speakers, with around 528 million speakers, or 44 percent of India’s population, followed by Bengali with around 97 million speakers, or 8 percent of the population. Marathi has around 83 million speakers, or 7 percent of the population, and Telugu speakers number around 81 million, or almost 6 percent of the population. Speakers who list the remaining official languages as their mother tongues also number between 2 and 4 percent of the population, as recorded in the 2011 census. It is interesting to note that due to India’s large population, native speakers of these regional Indian languages often outnumber native speakers of other major world languages such as Korean—with 77.2 million native speakers—and Italian—with 67 million native speakers—as of 2020.3

Languages in India are categorized into language families based on their different linguistic origins, which often include different scripts as well. The main language families include Dravidian, Indo–Aryan, and Sino–Tibetan. Bodo is the Sino–Tibetan language spoken in northeastern Indian states with the most speakers (1.4 million). Languages considered to be mother tongues or regional languages in the south of India have grammatical structures and scripts with Dravidian roots, and languages used in the central and northern regions of India are part of the Indo–Aryan family of languages. Many central and northern Indian languages use scripts derived from the Nagari script. Contemporary variations of Hindi use the Devanagari script, and scripts used in Gujarati, Punjabi, and Marathi use Nagari-derived scripts or versions of Devanagari that include some differences in their alphabets.

Similarly, Modern Standard Hindi and Urdu are grammatically identical, though they often differ in some vocabulary and their use of scripts, as Urdu uses a modified form of the Perso–Arabic script. As Hindi and Urdu are often considered to be one language with two scripts, a common belief is that the distinction among speaking and writing Hindi and Urdu falls along a religious divide between Hindus and Muslims, where Hindus are listed as Hindi speakers and Muslims as Urdu speakers in government documents such as the census.4 However, in practice, the distinction between Hindi and Urdu speakers is much more fluid and complex, as linguistic boundaries rely more on geographic location and speech community.

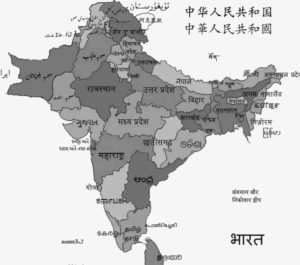

Another aspect of India’s multilingualism is that each mother tongue, or regional language, roughly belongs to one or more states. India’s twenty-eight states have been largely organized along linguistic lines since the 1950s, just after Independence, with the formation of the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh in 1953 for Telugu speakers. Andhra Pradesh was created after prolonged protests and strikes by Telugu speakers, which included the prominent activist Potti Sreeramulu fasting for the creation of a Telugu state until his death in 1952.5 A new state was finally created in 1953 by dividing the Tamil- and Telugu-speaking regions in what, under the British, was called the Madras Presidency. Immediately after Independence, the country retained similar political divisions it had under colonial rule, which newly independent Indians felt did not accurately represent them in the new government. The state reorganization movement for Andhra Pradesh culminated in the government-organized Dhar commission, which was ordered to investigate reordering additional Indian state borders along the lines of linguistic communities, or groups of people who speak the same language. The commission produced the State Reorganization Act of 1956, which called for states to be formed to represent linguistic groups rather than to stay the way the country was divided over the course of British rule.

Following the division of the state of Andhra Pradesh and the orders of the State Reorganization Act of 1956, the states of Kerala, Mysore, and Madras were formed. (In 1969, Madras was renamed Tamil Nadu, and in 1973, Mysore was renamed Karnataka.) In 1956 as well, the princely state of Hyderabad was divided between Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh. Just as the state of Andhra Pradesh was formed after prolonged protests for the rights of Telugu speakers, the Province of Bombay was also divided between Marathi and Gujarati speakers in 1960 into the states of Gujarat and Maharashtra. The bustling port city of Bombay, later renamed Mumbai in 1995, became part of the state of Maharashtra. Large reorganization efforts along the lines of language and religious communities continued with the 1966 reorganization of Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU) and Punjab into three new states, Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh; and India’s northeastern region also underwent a linguistic and communal reorganization into different states between the years of 1963 and 1987.

Multilingualism in India has therefore played a key role in the country’s contemporary politics. State boundaries were drawn along the lines of language groups, even though regions remain linguistically diverse, because languages in India can be an important way of defining one’s identity. Many people in different Indian regions in cultural and religious groups retain distinct identities that set them apart from other communities through language. As India is culturally, ethnically, and religiously diverse, language is one way people maintain group identities. Identity politics have also made mother tongues an object and mode of political struggle. Authors of the State Reorganization Act felt that democratic participation would grow if local populaces could access information and participate in government programs in their mother tongues. Language is a basis of identity and is why, when state boundaries were being redrawn after Independence in 1947, languages and the areas in which they were spoken were utmost factors of importance in where the boundaries of new Indian states would be.

Today, there are twenty-eight states in India and eight union territories, or areas directly governed by the federal government, and each state has at least one official language and many have two, in addition to English. In this way, with unique languages and scripts attributed to each state, India often seems like a collection of distinct countries due to the cultural and linguistic differences between states. Due to this vast diversity in languages and the way language is closely tied to identity, sometimes there are also struggles along religious and political lines that play out through language. Hindu nationalists engage in movements to spread the use of Hindi and Sanskrit as a means to spread the Hindu religion as well. Some have also felt that the distinct regional languages of states should indicate that people who do not speak those languages from birth should not be allowed to reside and work in states where they do not belong to the linguistic community. This was the message of the conservative party, the Shiv Sena, in Maharashtra.

English as an Indian Language

Adding to the complexity of the history of languages in South Asia, the English language was also integrated into the social fabric of the region insofar as it played a key role as a unifying language in the Constitution among north and south India at the time of Independence in 1947. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), also known by the name Mahatma, which means “Great Soul,” was a famous activist who led many Indians in peaceful protests against British rule. Gandhi and his supporters made concessions for the English language to remain in use in the new nation. They found English incredibly useful for unifying the country despite their support for Hindustani, the name for the mix of Hindi and Urdu commonly used in the northern regions of India, as the national language.

Paradoxically for Gandhi and his supporters, English represented a dividing force that emphasized the distance between educated Indian elites, who were more aligned with British colonizers, and non-English-speaking, often-uneducated masses. Gandhi maintained that to have a successful Independence movement was to govern through Indian ways, including through Indian regional languages. During the late colonial period, Gandhi addressed audiences from 1916 to 1928 over English linguistic colonization in education. He called for education in regional languages, stating, “The question of vernaculars as media of instruction is of national importance,” and he criticized how “English-educated Indians are the sole custodians of public and patriotic work”; he also said the “neglect of the vernaculars means national suicide.”6 However, the question of a national unifying language at Independence was a complicated one, as Gandhi’s call for Hindustani to wholly replace English was also rejected. Hindustani, later known as a variety of Hindi and Urdu, is not commonly spoken across all of India, and it is considered a northern Indian regional language since it is distinct from the language families and scripts used in south India. English, therefore, served as a utilitarian language to connect disparate and diverse areas of the newly unified country, as it still does today. Now, Indian English, with a unique vocabulary and accent, is a recognized variety of English in the world.

Ultimately, the English language was written into India’s new Constitution as a language to help with the new country’s transition from a British colonial subject to independent governance. Specifically, the 1949 original Constitution of India states that “business in Parliament shall be transacted in Hindi or in English” in Article 210, Article 343 states that “the official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script” and “for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement: provided that the president may, during the said period, by order authorize the use of the Hindi language in addition to the English language.”7 The intention of including English as a language for official government purposes along with Hindi was that English would be shed as the new nation matured.

In 1963, the impending transition away from English brought about similar concerns over the need for a unifying language, which were voiced at the time of Independence. Parliament enacted the Official Languages Act of 1963 to continue the use of English and section 3 of the act extended the implementation of English for official purposes along with Hindi.8 India decided to keep English as a unifying language to connect parts of the country where Modern Standard Hindi is not commonly spoken, such as in the southern Indian states with different scripts and language roots. While English is also a legacy of the British in India, it remains a tool and window through which to gain wider knowledge and understanding of the country. English also connects India with other English-speaking regions of the world.

Multilingualism in Daily Life

As there are many languages in India, many Indians can speak, read, and/or write in multiple languages, and multilingualism therefore is a part of daily life. Challenges and advantages of linguistic diversity affect the everyday lives of Indians in terms of businesses, educational institutions, and media. Due to the widespread use of English in India, the country is home to many international companies where English is commonly used for work. As English fluency often means higher socioeconomic status in India, middle- and upper-class Indians who have greater access to English have relative ease when working, studying, traveling, and immigrating to areas of the world where English is a lingua franca, or common language.

English is used in many office settings, especially in the international businesses and multinational corporations housed in India. Businesses in Indian cities hire employees from all over the country, and English is a common language among people with different mother tongues. In shops and supermarkets, many labels are written in English in the Roman script.

Other than English in business and commerce, many people also use Modern Standard Hindi as a common language, especially in the northern regions of India. In many of these places, mixing two or more languages or language varieties together when speaking is a prevalent practice known as “code-switching.”

Example of code-switching in conversation:

Waiter: Aur chahiye ? (Do you want anything else?) [Hindi] Man: Don coffee pahije (We want two coffees) [Marathi]

Code-switching as a practice is distinct from commonly used English words that have been subsumed into other Indian languages, which are called “loan” or “borrowed” words.9 While English and forms of code-switching are incorporated into Indian corporate culture, many people find themselves facing barriers to communication in these settings if they are not fluent in English or Hindi.

Example of loan words:

Teacher to the class: OK, all of you, open like this. Saglyana asa ghya aani, first page ogu-da, first page war kay lihile ? (Everyone take it like this and open to the first page. On the first page, what is written?) [English and Marathi]

The merits of multilingual education have dominated the field of education policy since the colonial period in India. Education in India is delivered in many different languages, but two languages are the most popular: English and Hindi. Additionally, many schools have instruction in students’ mother tongues or the regional state language as well. A plan for trilingual learning, called the three-language formula (TLF), was adopted into education policy by the Ministry of Education in 1968 and has been in discussion in parliament since 1948, just after Independence. The three-language formula requires schoolchildren to “(a) study and to receive content area instruction for twelve years in their mother tongue or the regional (state) language (which for some children will be one and the same); (b) study Hindi or English for ten to twelve years; and (c) study a modern Indian language (i.e., any one of the “scheduled” languages) or a foreign language for three to five years.” However, implementation of the TLF varies widely across the country today, with many English-language schools teaching limited English or only using English books and classroom materials. The idealized linguistic model presented in the 1968 TLF policy is meant to prepare students to be trilingual should students choose to enter the predominantly English-language higher education system and/or a globalized workforce. Proponents of multilingual education in India call attention to the importance of the three-language formula in adequately preparing primary and secondary school students for the linguistic demands of higher education, while also maintaining the rich linguistic heritage of India.

Even outside of education and business, Indians encounter English and multiple other Indian regional languages in media every day. They are especially likely to speak or read English in their daily lives if they are among the middle and upper socioeconomic classes, as increased English fluency aligns closely with socioeconomic class. There are many print media publications such as newspapers and magazines in English. Each city has at least one local English-language publication, and major print and online national publications can be found in Hindi and English. Each state’s news media publications are most commonly consumed in regional languages.

Visual media as well caters to regional language-speaking audiences, where local news broadcasts will be in the regional language and national news segments or specific programs will take place in Hindi. It is also becoming increasingly common for English to be used as part of code-switching practices in visual media, though English-only Indian broadcasts may be available at certain times or through special subscriptions or satellite television programming. In India, many regions have local film industries as well, where movies and television shows are produced in regional languages. Bollywood, the largest film industry in India, is located in Mumbai in the state of Maharashtra and produces films in Hindi. Bollywood movies are popular all over the world and can be viewed with subtitles for non-Hindi-speaking audiences. Interestingly, as of yet, no mainstream visual entertainment media industry in India makes English-only film or television productions, unlike in news and online digital media. It cannot be emphasized enough that as access and proliferation of English varies substantially along socioeconomic class lines, access to English in business, education, and media is linked to international capital and has a great capacity to increases one’s economic and social position.

As a multilingual country, India’s diversity has proven to be both a strength and a challenge to unifying the nation. Hopefully, this essay illustrates how multiple languages have shaped policies from education to the political boundaries of states, and, stemming from a colonial footprint and global pressures for greater use of English in international networks, the high demand for the use of English in India.

One can see there is a careful balance to multilingualism in India. English and languages like Hindi are deemed necessary for interaction in national and international communities beyond state and national borders, while mother tongues or regional languages are also made relevant through local state governments, institutions, and cultural identity. In this way, the cultivation and practices of multilingualism in India lends itself to more than just a preservation of unique, regional identities but has great impact on how Indians interact with fellow Indians and much of the world. Multilingualism in India defines the nation within global and national networks and communities for business, education, and media. As language plays an important part in our daily interactions, multilingualism and linguistic diversity in India have shaped the country and unique cultural practices and policies within it.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- “2011 Census Data,” Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, https://tinyurl.com/y66egqfl .

- See the Eighth Schedule of The Constitution of India, 1949

- Ethnologue, Languages of the World . Web archive (1992) at the Library of Congress at https://tinyurl.com/y6s2yjd3 .

- Christopher Rolland King, One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in the Nineteenth Century North India (Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Lisa Mitchell, Language, Emotion, and Politics in South India: The Making of a Mother Tongue (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009).

- M. K. Gandhi 1917 as cited in Speeches and Writings of M. K. Gandhi 1922, https://tinyurl.com/ybxaft9e , 307.

- Articles 210 and 243 of The Constitution of India, 1949

- Official Languages Act, 1963, section 3

- Harold F. Schiffman and Michael C. Shapiro, Language and Society in South Asia (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1981).

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Exploring Linguistic Diversity in India: A Spatial Analysis

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 11 March 2019

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Rajrani Kalra 4 &

- Ashok K. Dutt 5

189 Accesses

In the context of the modernization debate, social scientists have argued that there is a negative association between linguistic diversity within the country and economic development. India is a land characterized by “unity in diversity” amidst a multicultural society. This is represented by variety in culture such as different languages religions, castes, house types, dance forms, and dietary patterns (Noble and Dutt, India: cultural patterns and processes. Westview Press, Boulder, 1982). Of these cultural traits, language is an important instrument of cultural identity since it is through this medium that different groups of people identify and communicate with one another and the world and express a sense of identity to a place. Often social tensions emerge when a certain segment of society feels ostracized from social and economic processes of development due to lack of knowledge of the dominant and prevalent language. Also, it is argued that the most linguistically diverse states in India are more literate and highly educated and have a positive sex ratio. Given this background, this research addresses the following three research questions: (1) What is the extent of linguistic diversity in India during 1971–2001 decades? (2) What factors explain the geographical patterns in linguistic diversity in India? (3) Are linguistic diversity patterns symbiotically related? This study utilizes spatial analytic techniques such as index of diversity and GIS analysis. The data on language was collected from Census of India for analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Adhikari, S., & Kumar, R. (2007). Linguistic regionalism and the social construction of India’s political space. In B. Thakur, G. Pomeroy, C. Cusack, & S. K. Thakur (Eds.), City society and planning: Essays in honor of Professor A.K. Dutt, Volume 2: Society (pp. 374–392). New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Brass, P. (1991). Ethnicity and nationalism: Theory and comparison . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brown, D. (1989). Ethnic revival: Perspectives on state and society. Third World Quarterly, 11 (4), 1–17.

Article Google Scholar

Census of India. (1971). http://www.censusindia.gov.in . Accessed 30 May 2003.

Census of India. (2001). Data on language. Statement 7. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/Census_Data_Online/Language/Statement7.htm . Accessed 30 June 2003.

Chittranjan, H. (2005). A handbook of Karnataka, Government of Karnataka . Bangalore: A Government of Karnataka Publication.

Conkling, E. C. (1963). South Wales: A case study in industrial diversification. Economic Geography, 39 (3), 258–272.

Dittrich, C. (2007). Bangalore: Globalization and fragmentation in India’s high-tech capital. ASIEN, 103 (S), 45–58.

Dutt, A. K., & Devgun, S. (1979). Religious pattern of India with a factorial regionalization. GeoJournal, 3 (2), 201–214.

Dutt, A. K., & Devgun, S. (1982). Patterns of religious diversity. In A. G. Noble & A. K. Dutt (Eds.), India: Cultural patterns and processes (pp. 221–246). Boulder: Westview Press.

Dutt, A. K., Khan, C., & Sangwan, C. (1985). Spatial pattern of languages in India: A culture-historical analysis. GeoJournal, 10 (1), 51–74.

Emeneau, M. B. (1956). India as a linguistic area. Language, 321 , 3–16.

Fishman, J. (1968). Some contrasts between linguistically homogeneous and linguistically heterogeneous polities. In J. Fishman, C. Ferguson, & J. Das Gupta (Eds.), Language problems of developing nations . New York: Wiley.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York: Basic Books.

Heitzman, J. (2001). Becoming a Silicon Valley: Bangalore as a milieu of innovation. Seminar, 503 (July), 299–330.

Kalra, R. (2003). Linguistic diversity changes in India: 1971–1991 . M.A. thesis, Department of Geography and Planning, University of Akron, Akron.

Kalra, R. (2007). Indian languages and their dissemination: 1971–1991. In B. Thakur, G. Pomeroy, C. Cusack, & S. K. Thakur (Eds.), City society and planning, Volume 2: Society (pp. 447–477). New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Khubchandani, L. M. (1993). India as a socio-linguistic area. In A. Ahmad (Ed.), Social structure and regional development: A social geography perspective . Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Nair, J. (2005). The promise of the metropolis: Bangalore’s twentieth century . New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Nettle, D. (1998). Explaining global patterns of language diversity. Journal of Anthropological Archaelogy, 17 , 354–374.

Nettle, D. (2000). Linguistic fragmentation and the wealth of nations: The Fishman-Pool hypothesis reexamined. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 48 , 335–348.

Nigam, R. C. (1972). Language handbook on mother tongues in census . Calcutta: Language Division.

Noble, A. G., & Dutt, A. K. (Eds.). (1982). India: Cultural patterns and processes . Boulder: Westview Press.

Pool, J. (1972). National development and language diversity. In J. Fishman (Ed.), Advances in the sociology of language (Vol. 2, pp. 86–99). The Hague: Mouton.

Rodgers, A. (1957). Some aspects of industrial diversification in the United States. Economic Geography, 33 , 16–30.

Sekhar, C. A. (1971). Social and cultural tables (Census of India 1971, series 1, India Part II-C i). New Delhi: Office of Registrar General India.

Sengupta, P. (2009). Endangered languages: Some concerns. Economic and Political Weekly, 44 (32), 17–19.

Shortridge, J. R. (1976). Patterns of religion in the United States. Geographical Review, 66 (4), 420–434.

Sonntag, S. (2017). Languages, regional conflicts, and economic development in South Asia. In V. Ginsburg & S. Weber (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of economics and language (pp. 489–508). Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Srinivas, A. (2018). Hindi’s migrating footprint: How India’s linguistic landscape is changing. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/hindi-s-migrating-footprint-how-india-s-linguistic-landscape-is-changing/story-ssstgK9b2xR9x4srulu6OJ.htmls . Accessed 17 Oct 2018.

Timm, J. (2018). Locating linguistic diversity in the USA. https://www.jtimm.net/2018/02/10/locating-linguistic-diversity-in-the-usa/ . Accessed 22 Sept 2018.

Tress, R. C. (1938). Unemployment and the diversification of industry. The Manchester School, 9 , 140–152.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (2010). Atlas of the world’s languages in danger . Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 3 Revised Edition.

Warf, B., & Winsberg, M. (2008). The geography of religious diversity in the United States. The Professional Geographer, 60 (3), 413–424.

Download references

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

California State University, San Bernardino, CA, USA

Rajrani Kalra

University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA

Ashok K. Dutt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rajrani Kalra .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, University of Kentucky Department of Geography, Lexington, KY, USA

Stanley D Brunn

Deutscher Sprachatlas, Marburg University, Marburg, Hessen, Germany

Roland Kehrein

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Kalra, R., Dutt, A.K. (2019). Exploring Linguistic Diversity in India: A Spatial Analysis. In: Brunn, S., Kehrein, R. (eds) Handbook of the Changing World Language Map. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73400-2_202-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73400-2_202-1

Received : 24 October 2018

Accepted : 24 October 2018

Published : 11 March 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-73400-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-73400-2

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Recent Posts

- LSE South Asia Centre

Christopher Finnigan

February 21st, 2019, linguistic minorities in india: entrenched legal and educational obstacles to equality.

0 comments | 94 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

There are over 1,369 different languages in India but many face the real threat of disappearing in the near future. P Avinash Reddy looks at the available constitutional protections as well as the institutional threats that minority languages face – and how affirmative action might hold the key to protecting them.

Language is a crucial and defining aspect in the life of every individual. Not only a medium of effective communication, it is a harbour of culture and systems of knowledge. Various activities and elements of life stem from ones’ own mother tongue. Language acclimatises the individual and the community to the surrounding environment by equipping them with the necessary knowledge, which has been accumulating and evolving together for centuries. In India, the data collected about mother tongues through the 2011 census showed 19,569 languages, which after linguistic scrutiny and categorisation resulted in 1,369 ‘rationalised’ mother tongues . Nearly 400 of these languages however are facing the threat of extinction in the coming 50 years. While this data speaks volumes about the linguistic diversity in India, it also highlights the continued need to protect and nurture the languages spoken by the minorities.

The protection of linguistic minorities: the constitution

Article 30 (1) of the Constitution of India provides a fundamental right to linguistic minorities to establish and administer educational institutes of their choice. The Constitution however, under Article 351, provides a directive to the Union to promote the usage of Hindi across India, so that it can serve as a medium of expression among the diverse population. This provision has an imperialising effect on the speakers of languages other than Hindi, and linguistic minorities are the ones who face the blunt of it, especially when English is also promoted across the country at the cost of local and regional languages.

The Constitution of India (Article 350 A) provides that every state must provide primary education in a mother tongue and also provide for the appointment of a ‘Special Officer’ for linguistic minorities (Article 350 B), who is responsible to investigate matters relating to linguistic minorities and report them to the President. Neither the constitution nor any piece of legislation however defines linguistic minority. It was in 1971, in the case of DAV College etc. v/s State of Punjab, and other cases, that the Supreme Court of India defined a linguistic minority as a minority that at least has a spoken language, regardless of having a script or not. In the case of TA Pai Foundation and Others vs State of Karnataka, it further held that the status of linguistic minority is to be determined in the context of states and not India as a whole.

The protection of linguistic minorities: commissions

According to the Report of the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities however linguistic minority status of a community is determined by numerical inferiority, non-dominant status in a state, and possessing a distinct identity. The report states that “exclusive adherence to a minority language is a leading factor that contributes to socio-economic backwardness, and that this backwardness can be addressed only by teaching the majority language”.

The Commission should have rather emphasised the need to develop mechanisms and institutional structures to accommodate linguistic minorities so that they do not fall into the traps of socio-economic backwardness merely because of the language they speak. Instead of addressing the gaps in the education system which makes invisible the language of the linguistic minorities, the commission recommends that such individuals and communities learn the majority language to survive. This is a clear acknowledgement of systematic state discrimination emanating on the basis of the language that an individual and community speaks. The state is responsible to create equal opportunities for everyone regardless of whether they belong to the majority or the minority but is clearly fails to do so.

A workshop on linguistic minorities, held in 2006 by the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities, lead to the recommendations that the term linguistic minority must be defined properly and that such a definition should then be used while framing a law to provide affirmative action based on socio-economic backwardness. Even though the criteria suggested for identifying socio-economic backwardness among linguistic minorities is the same as that applied while identifying backward communities in India, to be regarded as more backward, the individuals among the linguistic minority must not have the knowledge of the majority language. This again is problematic as the additional criteria to determine the backwardness of a linguistic minority group should not be the lack of knowledge of the majority language. Instead it should be the vulnerability of the particular language to extinction, lack of institutional support to develop, sustain and promote a language.

It is necessary to emphasise that the mere knowledge of the majority language does not alleviate the backwardness of the linguistic minorities and that it can only be achieved by integrating the minority languages into the education system. This will help in preserving such languages and the associated knowledge systems while also easing the process of learning for students belonging to linguistic minorities. The recommendations of the workshop can only be aptly referred to as half-hearted attempts to integrate the minority languages into the education system. While it does provide that the teachers in schools with sizable linguistic minority must know the minority language, it does not suggest any steps to ensure that the medium of education should be in the minority language for students belonging to the particular linguistic minority. It only means that the state is trying to impose assimilation on linguistic minorities by not providing them adequate support to integrate their language in the education system.

Affirmative action and language

The most vulnerable among linguistic minorities are those belonging to tribes. Despite the vulnerability of their languages, there are hardly any government schemes or mechanisms that try and integrate these languages into the education system. Most of the linguistic minorities in India belong to indigenous groups and hence, they can avail reservation in Institutions for Higher Education under the Scheduled Tribe (ST) category. This, in essence, amounts to linguistic discrimination to impose assimilation on such students through the primary and secondary education system by instructing them in a majority language. It even paves the path to disappearance of languages as the individuals belonging to the linguistic minorities are assimilated into the majority language and culture at the cost of their own language. Especially in a scenario where the government itself promotes assimilation into the majority regional language or English by offering it as a means of alleviation from backwardness, it creates a strong dichotomy between retaining one’s own language and upward social mobility. Since the medium of instruction is alien to the students belonging to the linguistic minorities, most of them discontinue their studies and the ones who continue with their studies, do it at the cost of their own language.

A High Level Committee on Socio-economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities in India rightly points out that the reasons for extremely low literacy rates among the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups are poor educational infrastructure, poorly trained teachers, lack of teaching in the tribal languages and completely irrelevant curriculum. Even the Draft National Policy on Tribal Groups acknowledges that the changing educational scenario can push many of the tribal languages into extinction and provides that education in mother tongue in the primary level of education needs to be encouraged. As many of the schools for Tribal Groups are witnessing a sudden shift to English medium of instruction , students belonging to the indigenous linguistic minorities are facing the blunt of it as they cannot understand their curriculum and are also losing their own language. Based on the above analysis, it is evident that most of students belonging to such indigenous linguistic minorities fail to utilize the benefits of affirmative action in the sphere of higher education.

It is high time that the government understands these gaps in the education system for the indigenous linguistic minorities and take the necessary steps to integrate the languages of the linguistic minorities into the education system. The available affirmative action can only be effectively utilised by the students of indigenous linguistic minorities if their medium of instruction is their own language and English/majority regional language is taught comprehensively as a second language. Therefore, paving the path towards “real education” of such students while also equipping them with a resourceful second language.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Photo Credit: Patrick Tomasso, Unslpash

P Avinash Reddy is studying Law at National Academy of Legal Studies and Research, India. He is the co-founder of DEVISE (Developing Inclusive Education), a charity that is working towards providing better access to opportunities in higher education to the children from rural areas.

- Click to email this to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

About the author

Related Posts

The myth of the false case: what the new Indian Supreme Court Order on the SC/ST Act gets wrong about caste-based violence and legal manipulation

April 10th, 2018.

Long Read: Why has Sri Lanka’s Transitional Justice process failed to deliver?

February 6th, 2019.

How do we live? Understanding poverty in post-war Sri Lanka

July 2nd, 2018.

“It is easy to be xenophobic, it is harder to be humanitarian” – Dr Meghna Guhathakurta

August 1st, 2018.

South Asia @ LSE welcomes contributions from LSE faculty, fellows, students, alumni and visitors to the school. Please write to [email protected] with ideas for posts on south Asia-related topics.

Bad Behavior has blocked 4826 access attempts in the last 7 days.

Your Article Library

Essay on indian languages.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

India is the home of a very large number of languages. In fact, so many languages and dialects are spoken in India that it is often described as a ‘museum of languages’. The language diversity is by all means baffling. In popular parlance it is often described as ‘linguistic pluralism’. But this may not be a correct description. The prevailing situation in the country is not pluralistic but that of a continuum. One dialect merges into the other almost imperceptibly; one language replaces the other gradually. Moreover, along the line of contact between two languages, there is a zone of transition in which people are bilingual.

Thus languages do not exist in water-tight compartments. While linguistic pluralism is a state of mutual existence of several languages in a contiguous space, it does not preclude the possibility of inter-connections between one language and the other. In fact, these links have grown over millennia of shared history. While linguistic pluralism continues to be a distinctive feature of the modern Indian state, it will be wrong to assume that there has been no interaction between the different groups.

On the contrary, the give-and-take between the languages groups has been very common, often resulting in systematic borrowings from one language to the other. The cases of assimilation of one language into the other are also not uncommon. Let us look at the nature of linguistic diversity observed in India today. According to the Linguistic Survey of India conducted by Sir George Abraham Grierson towards the end of the nineteenth century, there were 179 languages and as many as 544 dialects in the country.

However, this number has to be taken with caution. It may even be misleading in the sense that dialects and languages were enumerated separately, although they were taxonomically part of the same language. Of the 179 languages as many as 116 were speech-forms of the Sino-Tibetan family, spoken by small tribal communities in the remote Himalayan and the northeastern parts of the country.

Even the 1961 census recorded 187 languages. This was despite the fact that the census investigation was far more systematic and the classification was based on modern linguistic criteria. Much of this diversity may be understood properly in the light of some more statistics. For example, 94 out of the 187 languages were spoken by small populations of 10,000 persons or less. In the final analysis, about 97 per cent of the country’s population was found affiliated with just 23 languages.

The diversity of languages and dialects is a reality and it is not the numerical strength of the speakers of a language which is important. The important fact is that there are people who claim a certain language as their mother tongue. Another related development which contributed to linguistic diversity was the development of script. Different Indian languages were written in different scripts. This made learning of different languages a difficult exercise. However, with the growth of scripts, written languages have been successful in maintaining their record with the consequence that literary traditions have evolved.

With the development of a script, oral communication is supplemented by a more powerful form of written communication. In the course of time some of the minor dialect and language groups have lost their identity as they have been assimilated into developed languages. It is a known fact that most of the languages still serve the purpose of oral communication only as speakers of these languages are still illiterate, or preliterate.

It may be assumed that in the beginning various speech communities were confined to their own enclaves, more or less unaware of the existence of other language/dialect groups in the neighbourhood. Sometimes, the boundary between two dialects, or two languages, was knife-edged, as it was described by a hill-line or a river. Within the enclaves, these groups have been communicating through a common language, or dialect, for centuries.

This became the basis of their identity. This traditional association with a language gave them a sense of belonging and thus inculcated in them a feeling of unity with the larger speech community. It may, however, be noted that inter-communication through a language or dialect is always limited in space. Individuals in their daily course of life have a limited reach. In situations where the communication is largely oral the sphere of communication is even smaller. Thus, with the passage of time, each speech community gets differentiated from other communities in the neighbourhood.

This process leads to splitting of the spoken language into diverse dialects. The dialect formation is, however, within the same speech area. With the expansion of the speech territory more dialect groups emerge and the distance between them increases. Sometimes the outlying dialects are so isolated from the parent language that they acquire linguistic nuances of their own sufficient enough to be recognized as an independent branch. A study of historical linguistics reveals that India has gone through all these phases of language development. The present linguistic map of India is naturally a product of these developments.

Language and Dialect:

The faculty of speech is by far the most distinctive human trait. Human beings use a system of language for communication which distinguishes them from the rest of the animal kingdom. It was through language that communication between the different members of a human group started in the early stages of social evolution.

Language thus facilitated multiple forms of human cooperation. Eventually, a division of labour emerged, a prototype of which is unimaginable in the animal world. However, there is no gainsaying the fact that animals also communicate with one another. They also produce vocal sounds although their sounds are simple.

One can differentiate between warning calls, mating calls and those expressing anger or affection. This system of communication is simple as it lacks structure. A structured language was the invention of the human mind, and the most effective tool of communication. In this language words could be replaced easily to change the content of meaning.

In its basic characteristics a human language is essentially a signaling system in which a variety of vocal sounds are employed. These vocal sounds are produced by the peculiar constitution of the human speech organs. There is a combination of the different speech organs— the tongue, glottis, vocal cords and the palate—in producing vocal sounds which are essential elements in human articulation of language.

It appears that in the beginning speakers of a language restricted their communication to relatively small number of vocal sounds out of the many sounds which human beings were capable of making. However, the number of vocal sounds varied from language to language which indicated variations in social evolution and the material conditions of existence. Most languages are satisfied with the use of twenty or thirty such sounds. But there are other languages which have as many as sixty sounds, or even more.

There are others which have less than twenty sounds. These sounds constitute the system of a language. As we know the purpose of a language is communication and a language sooner or later tends to become symbolic, more complex and expressive of abstract ideas. The beginnings of all languages were, however, simple.

There are very specific purposes for which the language is used. The main purpose is, of course, to express oneself, to convey one’s feelings, sometimes to express a desire or pray for help. The human beings also communicate their ideas through body language either alone or in combination with vocal sounds or words.

Even today, the body language continues to be a powerful means of expression. The exchange of ideas, feelings and calls for pray or help continue in the daily course of life of a human being. Thus, an intricate pattern of human cooperation and a feeling of togetherness is evolved. It is obvious that a language needs a group of people among whom communication continues through this language.

This group of people who communicate in a certain language may be described as the ‘speech community’. In the course of time, several speech communities are formed, each occupying a chunk of a geographically contiguous space (Fig. 6.1).

Each language eventually expands over a territory, homogeneous in terms of its language structure—vocal sounds, words, sentences and conventionalized symbols. When a language is written in a script it lends to stabilize its distinguishing features and promotes communication over long distances between people.

Origins of Language:

Origins of language are shrouded in mystery. However, it is possible to reconstruct the bits of this history. It is generally agreed that in the history of social evolution language must have arisen with the discovery of the art of tool-making. Understandably, the early tool-making communities must have depended on cooperation between different members of the group on a highly organized basis.

This would have been possible through the use of a language. Thus evolution of language must have progressed hand in hand with the evolution of material cultures. As the history of material cultures shows the change in techniques of tool-making was initially slow, but later on it picked up. Language also evolved with the same pace. Expressions became more and more complex with the passage of time. In fact, at every stage of evolution, there was a direct relationship between material culture and the language in use.

Evidently progress in material cultures shows that the functions of brain were becoming more and more complex and with these changes language also became complex. The way languages evolved from vocal sounds to words and sentences revealed how they became symbolic as humans tended to express abstract rather than concrete ideas.

It is obvious that in the course of evolution many languages were invented independently at different points of time in different regions of the world. They became further ramified as the social space within which inter-communication continued was always limited (Box 6.1). As a result, new groups were formed and new speech communities came into being.

This is how the ‘families of languages’ developed. It is also understandable that the early languages were oral and writing became possible much later. In the beginning there was no need for maintaining a written record. When such a need arose writing was initially mostly pictorial.

The discovery of the script in the history of development of languages must have taken a painstakingly long time during which picture/signs became conventionalized. Our knowledge of the early scripts is still incomplete. For example, the script of the Indus valley (Harappan) civilization continues to pose difficulties. We have not been able to decipher it simply because we are not familiar with the system of language in which communication was conducted by the Harappan people.

India as a Linguistic Area:

Despite the widely perceived linguistic diversity India’s unity as a socio-linguistic area is quite impressive. Several linguists have analyzed the basic elements of India as a socio-linguistic area. Describing language as an ‘autonomous system’, Lachman M. Khubchandani recognized the major characteristics of the speech forms of modem India. Each region of the country is characterized by the plurality of cultures and languages “with a unique mosaic of verbal experience”. In Khubchandani’s view modem languages of India represent a striking example of the process of diffusion, grammatical as well as phonetic, over many contiguous areas.

However, he considers linguistic plurality only as a superficial trait. “Indian masses through sustained interaction and common legacies have developed a common way to interpret, to share experiences, to think.” What has emerged is a kind of organic plurality, although the geographical distribution of speech communities suggests a kind of linguistic heterogeneity.

Some of the basic elements of India’s linguistic unity may be seen in the fuzzy nature of language boundaries, fluidity in language identity and complementarity of inter-group and intra-group communication. Khubchandani also emphasized the need of linking languages with the ecology of cultural regions described by him as kshetras.

As a language area India is being put to mutually contradictory linguistic interpretations which confuse the issue. Perhaps a better understanding of the linguistic scene can be developed if the static account of the multiplicity of languages is replaced by recognition of the elements of cultural regionalism. Similarly, the issue of linguistic homogeneity which has been argued by several linguists is fraught with complexities. In this context, one can cite the example of the states of the Indian Union carved out on the principle of linguistic homogeneity. The reality is that these states are not necessarily homogeneous in their language composition and cultural attributes.

In an earlier study, Khubchandani examined the evidence on plural languages and plural cultures of India. He dwelt upon the question of language in a plural society. The processes of language modernization and language promotion were also analyzed on the basis of a review of the language policies and planning in India. In this work, Khubchandani noted that people in certain regions of India displayed a certain degree of fluidity in their declaration of mother tongue. On this basis, he recognized two zones in which the country could be divided: a fluid zone and a stable zone. The fluid zone extended over the north-central region where Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Kashmiri and Dogri are spoken.

The stable zone, on the other hand, incorporates western, southern and eastern regions. People in these regions did not reveal any fluidity in their mother tongue declaration. Reference may also be made to the seminal work of Murray B. Emeneau who analyzed the characteristics of India as a language area. Tracing the history of development of the Indo-Aryan and the Dravidian languages he evaluated the shared experiences of the different speech communities.

Emeneau defined linguistic area as “an area which includes languages belonging to more than one family but sharing traits in common which are found not to belong to other members of (at least) one of the families”.

Geographic Patterning of Languages:

The geographic patterning of languages in the South Asian sub-continent can perhaps be understood in the context of the space relations the region had with other parts of Asia. As already pointed out, the sub-continent marks a southward projection of the Asian landmass into the Indian Ocean. The overland connections with West and Central Asia, Tibet, China and other regions of Southeast Asia helped the process of infiltration of linguistic influences into the South Asian region.

This is evident from the fact that the languages spoken in the peripheral regions of South Asia, such as Baluchistan, Pak-Afghan borderlands, Kashmir, Gilgit, Hunza, Baltistan and Ladakh as well as the hilly parts of Himachal Pradesh and the regions in the Northeast have strong affinity with the languages spoken in the regions beyond the Hindu-Kush Himalayas. The remote Himalayan areas became the abode of Tibeto-Chinese languages. Similarly, the Northeastern region continued to receive influences from the neighbouring parts of Myanmar, Thailand and Indo-China. These regions are now the domain of the Tibeto-Chinese (Sino-Tibetan) or Tibeto-Burman languages.

The people in the plains of North India from Sind to Assam acquired different branches of the Indo-European family of languages. The peninsular region continued to retain the Dravidian speech-forms even though the north was completely swayed over by the Indo-European languages. Between the Indo-European and the Dravidian one finds the Austric-speaking tribes nestled in the hills of the mid-Indian region.

The linguistic heterogeneity of India can perhaps be brought to some order when one realizes that these speeches really belong to four language families: Sino-Tibetan (Tibeto-Burman), Austro-Asiatic, Dravidian and Indo-European. In the course of usage over millennia of years these language families have found for themselves niches in the Indian social space in different parts of the sub-continent.

Their geographical patterning throws some light on the routes through which these language families reached India. In fact, despite the vast heterogeneity, Indian languages experienced parallel trends in linguistic and literary development during the long phases of shared history. This has made India ‘a composite region’ in terms of linguistic attributes (Table 6.1).

Historical Process of Language Diffusion:

The history of Indian languages is not easy to reconstruct. As an overview of the processes of peopling of India shows, Negroids were the first people to arrive. However, we do not exactly know about their language affiliation. The subsequent waves of migrations were so strong that the Negroids lost their identity completely, leaving behind little traces of either their racial or linguistic past.

The story of the four families of languages may be briefly recapitulated here, although it is not easy to establish the chronological sequence in which the speakers of the Austric, Sino-Tibetan and the Dravidian languages came to India. It is almost certain that these families were already there at the time of the advent of the Indo-Aryan.

This is, however, an established fact that the Sino-Tibetan speech communities were Mongoloids racially. The original Sino-Tibetan, the parent of the early Chinese, is supposed to have developed somewhere in western China around 400 B.C. It is also believed that the diffusion of this language eventually affected the regions lying to the south and the southwest of China-Tibet, Ladakh, northeastern India, Myanmar and Thailand. Perhaps, the Vedic Aryans were familiar with this group. They described the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Mongoloids of the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining regions as Kiratas.

The speakers of the Kirata family of languages are distributed all along the Himalayan axis from Baltistan and Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh. They occupy the regions surrounding the Brahmaputra valley in the northeast from Nagaland to Tripura and Meghalaya. There are striking differences between the languages of the Kirata family distributed over such a vast geographical area. The speakers of the Tibeto-Himalayan branch of the Kirata languages occupy the Himalayan regions from Baltistan to Sikkim and beyond to Arunachal Pradesh.

The Bhotia group consists of the Balti, Ladakhi, Lahauli, Sherpa and the Sikkim Bhotia dialects. Linguists also recognize a Himalayan group consisting of Lahuli of Chamba, Kanauri and Lepcha which is distinguishable on the basis of certain linguistic traits. In the east there is a North-Assam branch including the dialects of Arunachal Pradesh, such as Miri and Mishing. In other parts of the northeast the languages belong to the Assam-Burmese branch and are divided into Bodo, Naga, Kachin and Kuki-Chin groups. The speakers of the Kirata languages came to India in different streams at different points of time. Understandably, the groups in the northwest were unrelated to the groups in the northeast.

Similarly, the Kachin and the Kuki-Chin groups followed separate routes of migration. This is why there is a vast variety of dialects within the Kirata family and the roots of linguistic heterogeneity go far beyond the Indian borders into the neighbouring parts of Tibet, Myanmar and Indo-China. Anthropologists as well as linguists believe that the Austric-speaking groups came earlier than the Dravidian-speaking communities. The Austric speech communities were already there in the mid-Indian region before the advent of the Dravidian. The present geography of the Austric dialect groups holds some clues to the historical processes of their diffusion into India.

Generally, the Austric family of languages is recognized as consisting of a Mon-Khmer and a Munda branch. The Mon-Khmer speakers belong to two separate groups, viz., Khasi and the Nicobarese, both separated by a distance of more than 1,500 kilometres which spans over an expanse of the Bay of Bengal. There is no clarity among the scholars about the routes taken by the speakers of the Mon-Khmer dialects. The Khasi speakers themselves are surrounded by other Kirata and Arya dialects in the Meghalayan plateau.

The advent of the Dravidian in India is generally associated with a branch of the Mediterranean racial stock which was already there in India before the rise of the Indus valley civilization. In fact, archaeologists believe that they were the builders of the Harappan civilization along with the Proto-Austroloids. The Dravidian speech communities were found over most of the northern and the northwestern region of India before the advent of the Indo-Aryan. However, following the rise of the Indo-Aryan in northwestern India, a linguistic change came and the Dravidian-speak- ing area shrank in its geographical extent.

The present distributions of the Dravidian dialects in different parts of North India, such as Baluchistan, Chhotanagpur plateau and eastern Madhya Pradesh, where Baruhi, Kurukh-Oraon and the Gondi are spoken respectively, suggest the earlier stage of distribution of this family of languages. In fact, Gondi is spoken in many parts of Central India from Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra to Orissa and Andhra Pradesh.

While Dravidian speech forms were in use for many centuries in the pre- Christian era, the literary development in the Dravidian speech community could take place only in the first few centuries after Christ. It is believed that the old Tamil, old Kannada and the old Telugu had already come into being by 1000 A.D. Malayalam acquired its form a little later. With the Vedic Sanskrit, a branch of the Indo-European, the Indo- Aryan established itself in northwestern India. It had definite relations with the different Indo-European languages, such as Persian, Armenian, Greek, French, Spanish, German and English. An early form of Indo-European seems to have genetic relations with the Hittite speech of Asia Minor.

The linguists have recognized a primitive form of Indo- European in its earlier stage of development. They called it Indo-Hittite. A branch of the Indo-European which had already established itself in Mesopotamia came to be described by the linguists as Indo-Iranian. It is this Indo-Iranian branch which spread over Iran and the northwestern regions of India by the middle of the second millennium B.C. Among the different families of languages spoken in India the Indo-European seems to be the last to arrive. The advent of Indo- European in the South Asian sub-continent brought about a major change in the linguistic affinity of the people of northern India.

The form of Indo-European which was spoken in India came to be known as Indo-Iranian or Indo-Aryan. Its advent in India is seen with the rise of the Vedic Sanskrit. However, the old Sanskrit changed into Prakrit and several speech forms developed in different parts of northern and western India. The region lying between Saraswati and Ganga, encompassing the upper Ganga-Yamuna doab and adjoining parts of Haryana, to the west of the Yamuna, became the stage for the transformation of classical Sanskrit into a Prakrit form. From this early stage of development of Prakrit came the different Indo-Aryan vernaculars which are now spoken in north-western, north-central, central and eastern parts of India.

The Suraseni emerged in the core region of the midland (Madhyadesa of the Purartas) as the popular language. Its core area extended over western Uttar Pradesh and the adjoining parts of Haryana. A developed form of this parent language is described by the linguists as Western Hindi (Fig. 6.2).

Around the core region of Suraseni other speech forms developed on the west, south and east. These languages formed an outer band around the core language. On the west and the northwest lay the Punjabi and the Pahari dialects. Rajasthani and Gujarati emerged on the southwest. On the east, a form of language, now known as Eastern Hindi, emerged in Kosali (Awadhi). Linguists believe that these outer dialects were all more closely related to each other than any one of them was to the language of the midland.

“In fact, at an early period of the linguistic history of India, there must have been two sets of Indo-Aryan dialects—one the language of the midland and the other the group of dialects forming the outer band.” This first stage was followed by a subsequent phase of expansion. As the population of the midland region increased expansion became a necessity. Thus, on the periphery of the languages of the outer band developed new speech forms which were by and large not related to the language of the midland.

For example, while Punjabi was closely related to the language of the upper doab it got transformed into Lahnda in southwestern Punjab. This language had little relationship with the language of the midland. With increasing distance changes became quite pronounced. The geographical distribution of the Indo-Aryan languages may be briefly summarized here as follows: The midland language occupies the Ganga-Yamuna doab and the regions to its north and south. This core region is encircled by different speech forms in eastern Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Further beyond in the west and the northwest, there is a band of outer languages—Kashmiri, Sindhi, Lahnda and Kohistani. The languages of this band may be described as constituting the northwestern group of the outer languages. On the southern periphery lies the Marathi. In the intermediate band are situated languages, such as Awadhi, Bagheli and Chhattisgarhi. On the eastern periphery lie the three dialects of Bihari, viz., Bhojpuri, Maithili and Maghadi. The Bihari is surrounded by Oriya in the southeast and Bengali in the east. The languages of the eastern branch of the Indo-Aryan extend further in the east where Assamese occupies the Brahmaputra valley (Fig. 6.3).

Linguists believe that the development of the Indo-Aryan languages completed itself through several phases. The Prakrits developed into two stages: Primary Prakrits and Secondary Prakrits. The Primary Prakrits which were the first to evolve out of the classical Sanskrit were synthetic languages with a complicated grammar.

In the course of time they ‘decayed’ into Secondary Prakrits. “Here we find the languages still synthetic, but diphthongs and harsh combinations are eschewed, till in the latest developments we find a condition of almost absolute fluidity, each language becoming an emasculated collection of vowels hanging for support on an occasional consonant. This weakness brought its own nemesis and from, say 1000 A.D., we find in existence the series of modern Indo-Aryan vernaculars, or, as they may be called Tertiary Prakrits.”

The last stage of development of the Prakrits is known as literary Apabrahmsa. It is supposed that the modern vernaculars are the direct children of these Apabrahmsas. The sequence of change was like this. The Suraseni Apabrahmsa was the parent of Western Hindi and Punjabi. Closely connected with it were Avanti, the parent of Rajasthani, and Gaurjari the parent of Gujarati. The other intermediate language —Kosali (Eastern Hindi)—sprang from Ardha-Magadhi Apabrahmsa. The chronological sequence may be roughly reconstructed here (Table 6.2).

The different stages through which the Indo-Aryan languages passed can be depicted as on Figure 6.4.

In a country where so many languages/dialects are spoken, and many of them are used for oral communication only, linguistic classification may not be an easy exercise. The scientific study of Indian languages, their grammar, phonetics and vocabulary which goes back to the nineteenth century is still ridden with problems.

For one thing, linguists are still unsure of genetic relationships between one language group and the other. Their knowledge of some of the minor languages is pathetically inadequate. This leaves the problem of classification always open to revision. A second set of problems arises from the recognition of the major languages and their specification in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

There were political compulsions under which some languages were given this special status. The Eighth Schedule mentions eighteen languages; twelve of them have their own territory where they receive maximum state patronage and seem to have great potential for development. The Eighth Schedule also includes languages, such as Sanskrit, Sindhi, Nepali and Urdu. The first three do not have a speech territory as such. The speakers of Urdu, Sindhi and Nepali are distributed across several states.