Why rejection hurts so much — and what to do about it

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

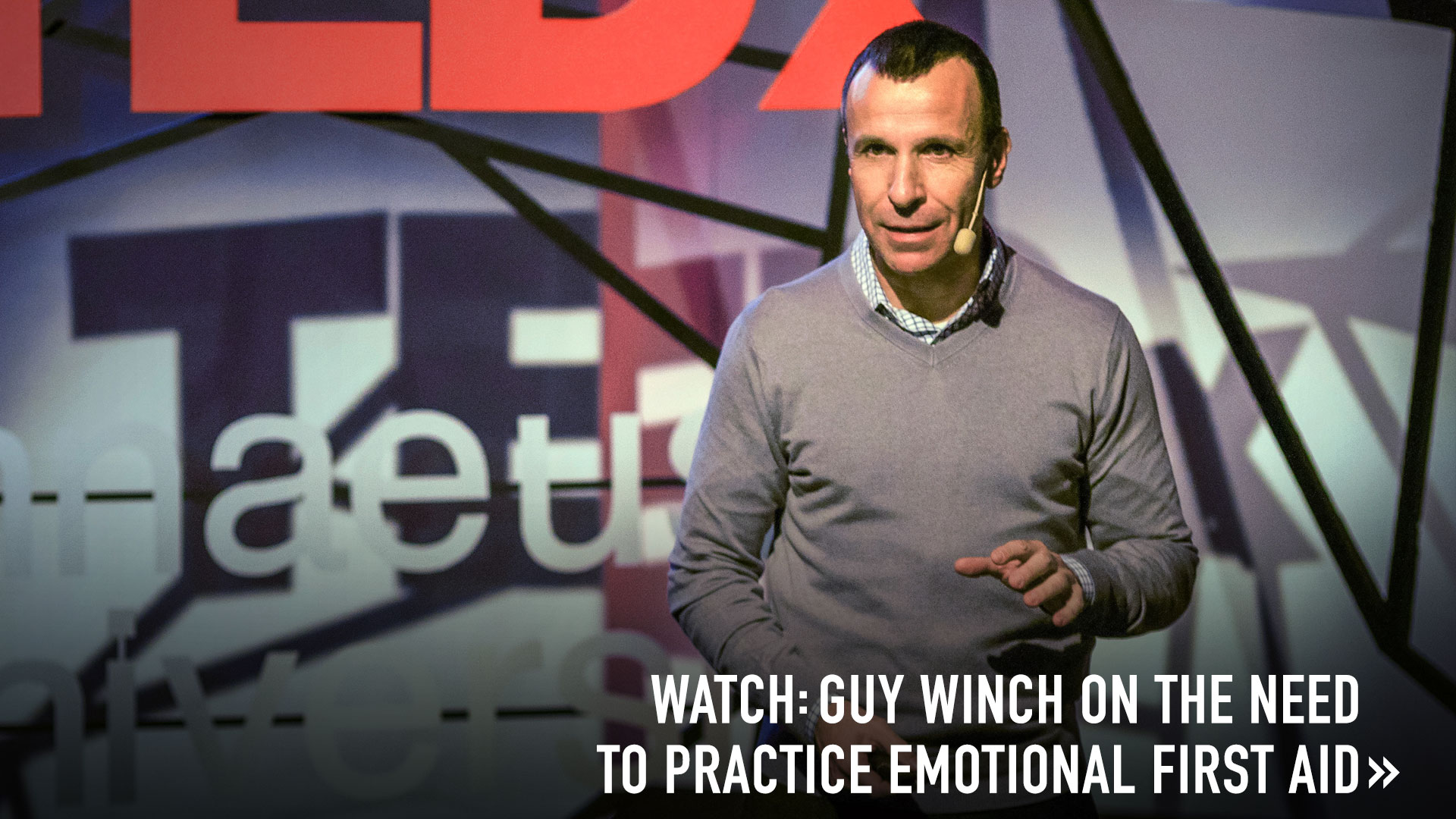

Psychologist Guy Winch shares some practical tips for soothing the sting of rejection.

Rejections are the most common emotional wound we sustain in daily life. Our risk of rejection used to be limited by the size of our immediate social circle or dating pools. Today, thanks to electronic communications, social media platforms and dating apps, each of us is connected to thousands of people, any of whom might ignore our posts, chats, texts, or dating profiles and leave us feeling rejected as a result.

In addition to these kinds of minor rejections, we are still vulnerable to serious and more devastating rejections as well. When our spouse leaves us, when we get fired from our jobs, snubbed by our friends, or ostracized by our families and communities for our lifestyle choices, the pain we feel can be absolutely paralyzing.

Whether the rejection we experience is large or small, one thing remains constant — it always hurts, and it usually hurts more than we expect it to.

The question is, why? Why are we so bothered by a good friend failing to “like” the family holiday picture we posted on Facebook? Why does it ruin our mood? Why would something so seemingly insignificant make us feel angry at our friend, moody, and bad about ourselves?

The greatest damage rejection causes is usually self-inflicted. Just when our self-esteem is hurting most, we go and damage it even further.

The answer is — our brains are wired to respond that way. When scientists placed people in functional MRI machines and asked them to recall a recent rejection , they discovered something amazing. The same areas of our brain become activated when we experience rejection as when we experience physical pain. That’s why even small rejections hurt more than we think they should, because they elicit literal (albeit, emotional) pain.

But why is our brain wired this way?

Evolutionary psychologists believe it all started when we were hunter gatherers who lived in tribes. Since we could not survive alone, being ostracized from our tribe was basically a death sentence. As a result, we developed an early warning mechanism to alert us when we were at danger of being “kicked off the island” by our tribemates — and that was rejection. People who experienced rejection as more painful were more likely to change their behavior, remain in the tribe, and pass along their genes.

Of course, emotional pain is only one of the ways rejections impact our well-being. Rejections also damage our mood and our self-esteem, they elicit swells of anger and aggression, and they destabilize our need to “belong.”

Unfortunately, the greatest damage rejection causes is usually self-inflicted. Indeed, our natural response to being dumped by a dating partner or getting picked last for a team is not just to lick our wounds but to become intensely self-critical. We call ourselves names, lament our shortcomings, and feel disgusted with ourselves. In other words, just when our self-esteem is hurting most, we go and damage it even further. Doing so is emotionally unhealthy and psychologically self-destructive yet every single one of us has done it at one time or another.

The good news is there are better and healthier ways to respond to rejection, things we can do to curb the unhealthy responses, soothe our emotional pain and rebuild our self-esteem. Here are just some of them:

Have zero tolerance for self-criticism

Tempting as it might be to list all your faults in the aftermath of a rejection, and natural as it might seem to chastise yourself for what you did “wrong” — don’t! By all means, review what happened and consider what you should do differently in the future but there is absolutely no good reason to be punitive and self-critical while doing so. Thinking “I should probably avoid talking about my ex on my next first date” is fine. Thinking “I’m such a loser!” is not.

Another common mistake we make is to assume a rejection is personal when it’s not. Most rejections, whether romantic, professional, and even social, are due to “fit” and circumstance. Going through an exhaustive search of your own deficiencies in an effort to understand why it didn’t “work out” is not only unnecessarily but misleading.

Revive your self-worth

When your self-esteem takes a hit it’s important to remind yourself of what you have to offer (as opposed to listing your shortcomings). The best way to boost feelings of self-worth after a rejection is to affirm aspects of yourself you know are valuable.

Make a list of five qualities you have that are important or meaningful — things that make you a good relationship prospect (e.g., you are supportive or emotionally available), a good friend (e.g., you are loyal or a good listener), or a good employee (e.g., you are responsible or have a strong work ethic).

Then choose one of them and write a quick paragraph or two (write, don’t just do it in your head) about why the quality matters to others, and how you would express it in the relevant situation. Applying emotional first aid in this way will boost your self-esteem, reduce your emotional pain and build your confidence going forward.

Boost feelings of connection

As social animals, we need to feel wanted and valued by the various social groups with which we are affiliated. Rejection destabilizes our need to belong , leaving us feeling unsettled and socially untethered.

Therefore, we need to remind ourselves that we’re appreciated and loved so we can feel more connected and grounded. If your work colleagues didn’t invite you to lunch, grab a drink with members of your softball team instead. If your kid gets rejected by a friend, make a plan for them to meet a different friend instead and as soon as possible. And when a first date doesn’t return your texts, call your grandparents and remind yourself that your voice alone brings joy to others.

Rejection is never easy but knowing how to limit the psychological damage it inflicts, and how to rebuild your self-esteem when it happens, will help you recover sooner and move on with confidence when it is time for your next date or social event.

Illustration by Dawn Kim for TED.

About the author

Guy Winch is a licensed psychologist who is a leading advocate for integrating the science of emotional health into our daily lives. His three TED Talks have been viewed over 20 million times, and his science-based self-help books have been translated into 26 languages. He also writes the Squeaky Wheel blog for PsychologyToday.com and has a private practice in New York City.

- relationships

- self-esteem

TED Talk of the Day

How to make radical climate action the new normal

6 ways to give that aren't about money

A smart way to handle anxiety -- courtesy of soccer great Lionel Messi

How do top athletes get into the zone? By getting uncomfortable

6 things people do around the world to slow down

Creating a contract -- yes, a contract! -- could help you get what you want from your relationship

Could your life story use an update? Here’s how to do it

6 tips to help you be a better human now

How to have better conversations on social media (really!)

Let’s stop calling them “soft skills” -- and call them “real skills” instead

3 strategies for effective leadership, from a former astronaut

There’s a know-it-all at every job — here’s how to deal

5 ways to build lasting self-esteem

How to beat loneliness

Why we need to take emotional pain as seriously as physical pain

Dear Guy: "I'm in quarantine, and I'm heartbroken"

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About Rejection, Overcoming Fear and Their ‘Word of the Year’

Teenage comments in response to our recent writing prompts, and an invitation to join the ongoing conversation.

By The Learning Network

This week on The Learning Network, our writing prompts asked teenagers to dig deep. One invited reflection on times they have benefited from rejection, another asked about how they have overcome their fears, and a third challenged them to come up with one word to encapsulate their aspirations for the year ahead.

Thank you to all those who joined the conversation this week from around the world, including teenagers from Savannah, Ga. ; Loveland, Colo. ; and Jiangsu Province, China.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

Have You Ever Benefited From Rejection?

An aspiring actor named Axel Webber went viral on TikTok recently — not for achieving his goal of getting into the Juilliard School, but for being rejected from it. His story led to thousands of reassuring comments from strangers and celebrities alike.

Mr. Webber’s post inspired us to ask teenagers if they had experienced rejection — and if the consequences had been different from what they expected. Over 200 told us about times when being turned down spurred them to work harder, reflect, grow and find a new path. Here is a selection.

Rejection Can Push You in a Positive Direction.

I believe that rejection is an opportunity for growth. When you are rejected it forces you to focus on what you need to work on to be better. So that if you go back, you can get the acceptance that is well deserved. Rejection motivates you to keep pushing and better yourself. Personally, I have been on my school’s dance team for 3 years, however, you have to try out to compete for our major competitions. For the first two years, I did not make the competition team. That rejection pushed me to work on my skills and work on getting myself stronger so that I can be ready. After all my hardwork, I am finally able to compete. So yes, rejection is a good thing.

— Royal, New Mexico

When I was younger, I submitted one of my Lego creations to a contest going on at the time. I unfortunately didn’t win or get any recognition whatsoever, and while that did sting at first, it ultimately gave me the opportunity to reflection on my failure. Analyze what aspects the winning entries did better than mine and through that, grow creatively going forward. At the end of the day if you wish you go forward you must prepare to occasionally be pushed backwards. So you can charge ahead stronger than your would’ve been able to before.

— Nolan, Glenbard West

Rejection can be a fuel for success. There have been multiple times in life where I have failed, but I had to pick myself back up to accomplish what was needed. For example, there was one time where I didn’t do so good on a quiz for math. I saw the grade and knew I wanted a better one. I signed up for retakes, looked over my work, and studied. I ended up getting an100 on that retake and it brought my grade up further than what it was before. Everyone needs a little bit of failure to succeed because at the end of the day that fail can be used as fuel for success.

— Emeka, Kenwood Academy

We Can All Learn From Defeat.

Rejection hurts- whether it be from a friend group or a college, the same thoughts are always triggered: “Am I good enough?” Some may think that these thoughts are purely harmful, but I would argue otherwise. These thoughts both encourage introspection by challenging a person’s preconceived notions of themselves, and ultimately help remove the idea of worth from all that is tangible. Furthermore, rejection helps people consider what is truly meaningful to them, by testing the relationship between person and want. If something is truly desired, a single rejection should not be enough to stop a dream, while it might give pause as people consider whether their fight is worth the effort for other things. This effectively selects for the things that are most important in a person’s life, and it is precisely this rejection that, through trial, empowers someone to live their best life.

— Brandt, Glenbard West High School

Of course, getting rejected hurts. As a senior, rejection is one of my biggest fears. At times, I am anxiously waiting for an email to see if I got accepted into the colleges I have applied to. Nevertheless, rejection is not the end of the world. Personally, I feel that rejection means it is not for me or it is not for me at that time. Furthermore, I have never let rejection make me feel like a failure. When I get rejected, I take it as a lesson on what I can do better next time. A lot of people are terrified of rejection; however, I feel that rejection helps me grow as a person. For example, if I get rejected from a college, I learn that that school is not for me and I won’t succeed there.

— Keiry, Don Bosco Cristo Rey High School

Rejection is something we are all familiar with. It’s a “must” in our lives. It’s something we encounter during our journey to success. I was in the doldrums when I experienced rejection. I knew what failure tastes like, but at the same time, the rejection pushed me and motivated me to go further. I just had to try again.

We should be open with our disappointments or unfortunate times. We should not be embarrassed and we should not avoid it, but we should embrace it. Once we face rejection with optimism and determination to attempt again, we know that we have nothing to lose. There would be a fervor created, there would be adrenaline pumping, and we become our brand new selves. More resilient, more diligent, more preserver.

— Bella, Suzhou SIP, Jiangsu Province, China

Hearing “No” Is Scary.

I can’t think of a time I benefited from rejection. In my opinion, rejection is a really scary thing. I generally avoid trying out things unless I am good at them. When I try something out and I’m struggling I feel humiliated. Facing the possibility of rejection is enough to make me not try it at all. Looking at this article he faced rejection from the university of his dreams very publicly. Then his fans harassed the Instagram of the university. I feel like that’s much worse than just getting rejected regularly.

— Shealynn, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

It’s Important to Talk About Failure.

I do think that it is important to discuss failures because it’s not the end of the world. I know a lot of people who have their whole lives planned out and are so set-in-stone with the path they want to take and I’m just wondering when it’ll fall apart. The saying “no plan survives contact with the enemy” rings true in so many aspects of life and the main theme of that saying is to be adaptable, to be prepared for the worst. The people who are so stubborn with their life plan are fragile because if something goes wrong, something they can’t predict, their entire world might seem like it’s falling apart. It’s important to set goals and strive for them, sure, but life is full of complications and not being ready for things to go wrong is setting yourself up for failure. By discussing failure and showing how life continues, people can be more comfortable with it and ready in case something happens they can’t expect.

— Max, Hinsdale Central IL

I think that it is very important to openly discuss the times we fail to achieve our goals. Nobody is perfect. People make mistakes all the time. Goals can be made, but they are more often unsuccessful or failed. However, people only ever talk about their achievements to look better and feel better about themselves. If you only ever hear about all the great things other people are doing, its going to negatively affect your mental health and self esteem if and when you fail to achieve one of your goals. Sharing your bad experiences, like Mr. Webber did, normalizes the very normal concept of failure. People can relate to it and feel better about their experiences. Additionally, people can see that you can recover from failures. Many think one is the end all and don’t care to look for the bright side and good things that can come instead. Mr. Webbers experience being shared can help people see that this is not the case. Failure and rejection one time wont make for failure and rejection all the time.

— Nina, Baker High School

By sharing our stories it allows for others to not feel so alone if they are going through a similar hardship too. It has been proven in many studies that by discussing and working through failure, it will help and benefit us in the long run. Suppose all individuals who faced failure and struggle opened up to others, there would be an overflow of support and love. All this support would help to create new goals and a new path was better than before. I think Mr.Webber chose to share his experience so that he can help others realize that failure and rejection doesn’t always mean the end of an era, just the beginning of another chapter.

— Delaney, Maury High School-Norfolk, VA

Rejection Is Not the End.

A common misconception in this day and age is the understanding that rejection is an irredeemable failure, suggesting that those who have been rejected have no hope of changing. However, this could not be further from the truth. While I agree they rejection should be treated as a sign of failure, we need to rethink the popular assumption that rejection indicates the inability to improve. For most people, rejection can be incredibly discouraging, as it may feel that one’s efforts amounted to nothing in the end. Though this is understandable, this view is shortsighted. The strongest people are those who acknowledge their faults and choose to improve upon them, or find other solutions such as Webber suggests in the article. This is something that society should take into consideration when faced with rejection in the future.

— Jose, Glenbard West

This is one time when rejection can actually help you by teaching you to be patient and keep moving. You may not get what you want right away, but if you’re willing to work hard and be patient, you will eventually find yourself where you want to be. You may experience sadness in the beginning, but you will realize that this is an opportunity. You may not realize it just yet, but you may become something even better than you hoped for.

— C., Bronx

How Do You Overcome Your Fears?

In a recent guest essay for the Opinion section, the poet Amanda Gorman revealed that she almost didn’t deliver the now-famous reading of her work “The Hill We Climb” at President Biden’s inauguration. Why? “I was terrified,” she confesses.

In the essay, she tells readers how she overcame her fears and why doing so was worth it. We asked students to reflect on Ms. Gorman’s advice and to share their own. They told us about the mantras they recite, the music they listen to, and the questions they ask themselves to work through their doubts.

What Amanda Gorman Can Teach Us About Fear

Unfortunately, fear is not something we can avoid, but something we must deal with. Ms.Gordon’s recitation of her experience with fear during her big moment conveys that no one is immune to fear, not even extraordinary poets and public speakers. This article humanizes fear as something that we all go through and I found it extremely powerful as the article reveals that fear doesn’t discriminate. It is important to remove the stigma and reformulate our feelings about fear and how fear doesn’t make one weak.

— Victoria, Westbury, NY

My fears have stopped me from doing many things I wanted to do. I have missed out on social events, school, etc. I have very bad social anxiety and I have a really big fear of people judging me. This has made it really hard for me to ask for help because i feel stupid when I do, and because of this, I’ve had many missing assignments just because I was too nervous to ask for help. After reading this article, I’ve realized that many people feel the same way and that you should not let your fears take you over because in the long run, you will look back and regret the opportunities you missed.

— Mckenzie, Loveland, Colorado

Fear keeps people from living. It traps us and convinces us that we are not up to the task, that we are too weak to struggle through. But Ms. Gorman’s advice helps remind us that the only possible way to truly get over our fears is to own them and face them head on. Although it truly is a struggle to gather up the courage to own our fear, in the end, if we follow through, the reward and accomplishing feeling is worth it. Ms. Gorman’s advice reflects this idea, so in the pursuit of getting over my public speaking fear, I will own it.

— Carlin, Glenbard West High School, Glen Ellyn

I struggle with ADHD and anxiety, both these diagnoses sometimes try to scare me out of doing even the smallest of things. The anxiety-ridden voice in my head tries to talk me out of going somewhere or doing something with the “What if?” questions: “What if you fail?” What if you get hurt?” “What if it doesn’t go the way we planned?” Something I have learned so I don’t pass on stuff that would probably regret is to quiet those voices because if I didn’t I would be like the speaker, Amanda Gorman, who almost passed on delivering her poem at Biden’s inauguration because of the “What ifs.” She figured out that if she missed out on that once in a lifetime opportunity because of being scared of the possible outcomes, she might regret it forever.

— Olivia, Block 4, Hoggard High School

Advice for Getting Through Scary Moments

Whenever my paranoid thoughts take over my mind, I say loudly to myself mentally, “Stop talking. Everything will be okay,” repeatedly. It works well when there is something I can distract myself with (like a crowd), but when there are times when I’m alone by myself, it does not work as well. I try my best to think positively and look at the good sides. “My parents will be proud of me. I will be proud of myself. This will be good for me.”

— Yang, J.R Masterman Philadelphia, PA

Presenting in front of the class or preparing for a presentation brings me anxiety; consequently, I use several techniques that help me remain relaxed so that these nervous feelings do not hinder my presentation. Like Ms. Gorman, I recite words of confidence and encouragement. This is an effective strategy because it allows me to realize that I am prepared for what is ahead. Additionally, I remind myself that the presentation will last for a small period of time. After it is over, the pressure will no longer be a burden. Another effective tool I use while talking to large groups of people is focusing on one spot in the crowd. This prevents me from directly reading off notecards, and forces me to face the audience I am speaking to. These approaches have aided to ease my anxiety and allowed me to present more comfortably in front of my classes.

— Javier, Maury High School, Norfolk VA

Learning to Deal With Fear or Anxiety

I was about 12 years old. I remember driving up to the Disney parks and seeing the biggest roller coaster of my life, and saying that I would never ride on it. Well, I was wrong. My mom had different plans for me. As we approached the ride, I was fine waiting for my family to do their thing, I even went as far as waiting by a churro stand as they were in line. But then my mom called me to at least wait in line with them, then I was ready to go, and she asked me to at least go to the front of the line, then to at least wait on the side as they went on the ride, then by some magical persuasion, I sat in the seat of my first roller coaster. I will admit, it was fun, and that I have never stapled my feet as hard to anything, but it was nice to separate myself from my fears, and experience something that I would have never predicted would happen, not die.

— Belle, Atrisco Heritage Academy

If I am dealing with anxious thoughts and doubt at a certain time, I think to myself, “What am I doing?” and “Does this really matter?” If the answer is yes, then I try not to think about it, as it would just lead to more stress accumulation or I try and relax before I make a decision. It is my personal belief that a decision made with emotions is a very rushed and illogical decision. After all that is done, I regroup and start to think of a solution and if I don’t think it’ll work, I’ll ponder a while more. Then I ask myself, “What’s the worst that could happen?” Then I go ahead with the decision. If I am overcome with fear and severe anxious thoughts, then I go with a obviously different approach. As much as this seems far-fetched, I tend to have an easier time with dealing with fear when I simply tell myself it’s just my head.

— David, Glenbard West High School

I always had this constant fear that something was lurking in the dark rather than fearing the darkness itself. To overcome this fear, I had to force myself to approach it logically and treat it as any other scenario. For example, if I were venturing into the basement of my house, I would say to myself that nothing was lurking in the dark and that it was unnecessary to think that way. Another example would be my fear of failure, which I still haven’t fully recovered from. This kept me from a critical opportunity when I scheduled to take the SAT, and I canceled the day before. I don’t regret this, but it was still saddening that my stress hindered me from following through. Moving forward, I plan to focus my efforts on reducing stress by facing these fears head-on with this mentality.

— Evan, Farmington High School

To overcome my feelings of dread or fear, I just turn on my favorite music from the 60-80’s. This tactic usually works, and I am able to get rid of any fears or dread by jamming out to these songs. Even though I don’t state my fears out loud or recite mantras, like Ms. Gorman, I am able to overcome them through joy and music. These approaches have been very effective for me and I have been able to lighten other people’s day because of it.

— MiKayla, Colorado

What’s Your Word of the Year?

A recent Well section newsletter shared the words readers had sent in that represent the positive changes they would like to make in their lives in the next year.

It inspired the Picture Prompt, “ Your Word of the Year ,” in which we asked students, too, to choose a word to represent their hopes for 2022, and to explain why they chose it. Here are some of the answers.

“Incandescent”

The past two years were filled with darkness and hopelessness, waiting for the pandemic to end, mourning the loss of those who have passed due to the virus, or any other tragedy that has The sense of loneliness and isolation hung in the air whenever we walked outside after being trapped indoors for so long with minimal contact and communication. This year, I hope for a bright, incandescent year filled with success and happiness. I hope for liveliness and energy, having the strength to reach new limits that have never been reached in the past. I hope to discover new fascinations, and rediscover old passions after two years of being bored and uninspired.

— Maria, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

Through this year I hope to embrace both the good and bad in my life. I hope to embrace both success and failure with open arms and cherish each experience. I want to embrace myself and those around me with nothing but love and acceptance. The last few years have been plagued with uncertainty and sorrow—making it challenging to focus on embracing all aspects of our lives. To heal this cycle, I’m dedicated to embracing everything 2022 has to offer, and truly appreciating life.

— Lucy, Glenbard West High School

“Adoration”

This is the first word that came to mind when I chose my word at the beginning of 2022. Adoration, as defined by dictionary.com, is “deep love and respect.” I want to adore my life, not just tolerate it. I want to live each day with intention, not merely surviving, but passionately living. I want this year, and every year moving forward, to be filled with feelings of adoration. I want to deeply love the people I surround myself with, not just tolerate them. I want to adore my sport, my school life, my routines, and my daily adventures. The pursuit to adore my life, to fall in love with every good thing it entails- adventure, joy, laughter, faith, fullness and goodness- will help me to have gratitude when life gets tough. There is always room to adore life and with that adoration comes great gratitude for life, even in long days and hard circumstances.

— Winn, Hoggard High School in Wilmington NC

“Satisfied”

There is no point in nitpicking our lives and finding a flaw in every little thing. To be satisfied is to be happy and content. Nobody likes to be around a complainer and nobody likes to be around the person who would clearly rather be somewhere else. Being satisfied with where you are and who you are with is the most important thing in my eyes. Make the people around you feel comfortable and enjoy your time with them, wherever you are.

— Clare, Glenbard West High School

“Improvement”

This year, I want to try and focus on myself the best I can and improve who I am mentally and physically. I want to focus on improving my health habits, finding the rights friends, and taking more breaks from toxic people and social media. I want to improve and become a better me for 2022 and just keep getting better. I am going to work hard in school, dance, and my mental health to improve who I am as a person. I want to find myself again and make my life better eventually.

— Kate, Syracuse, NY

This is the year where I will improve my skills and grow them. I have a bad habit of procrastinating, and I plan on growing out of it this year. I am also in a running sport and would like to run faster and grow out of my old self. This is the year we all have to step up and get onto the task. The pandemic has taken away a lot of our productivity these past two years, and we have to get back on track. We certainly won’t be going back to normal, but that is why we have to grow into something new and better.

— Rithvik, Mission San Jose

“Persevere”

I think during these times especially, we all need this the most. We all need to remember to keep going even when things get tough. As a junior in high school, my life right now is pretty stressful. I’m preparing to apply to colleges, getting ready to take the SAT, balancing a job and school, all while being in a pandemic. Although things are really hard for everyone right now, I always tell myself to persevere. Even though sometimes I just want to give up, I remind myself of my goals, and what I want to accomplish. I know that giving up will prevent me from accomplishing my goals. Overall, this year will be extremely stressful and scary, but I think we all need to do one thing—persevere.

— Marissa, Glenbard West HS

“Pragmatic”

This word, other than being the word for this year, is my favorite word. According to the Google definition, pragmatic means “dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations”. I want to dive into 2022 realistically and sensibly, especially as my junior year in high school comes to an end and I start to plan my life out moving forward. I don’t want to overwork or dissappoint myself this coming December, but I also don’t want to regret anything I didn’t do.

— Elizabeth, Glenbard West High School Glen Ellyn, IL

I believe if you stay calm and relaxed you can achieve so much more. You could also have less stress, less anxiety, depression and so much more. By staying calm you can just think about the good and never the bad, you can be around more people and not be anxious. Staying calm can also improve relationships with others. When being calm with people you won’t be so quick to think about something the wrong way, and can take that information and process it to where you understand it better. You can also manage your energy, and not always burn yourself out, and you won’t be nervous about a lot of stuff. Calmness can improve your creativity and how you may have seen things before, you may see them totally differently than how you see things now.

— MW, Hoggard High School in Wilmington, NC

I have found that focusing on one’s own self - as in their interests, hobbies, and personality brings so much peace and ease to their life. Since quarantine, other people’s choices and opinions have been affecting me in different ways, to where I started questioning everything I do and say. After months of isolation, returning to the ‘real world’ had come with difficulties, but with this new year, I pursue a future of confidence and perseverance. I will continue doing the things I have recently found and loved, as well as embrace and discover new interests I’ve been too scared to try. 2021 was a good year for me, and a huge leap from 2020. Everyone started gradually returning to their lives, jobs, school, and more. I started enjoying life as it is and gained so much confidence in myself this year, and I am so grateful for all the blessings it has brought me. 2022, on the other hand, will hopefully be a better year of discovery and hard work. As The editor of the Well newsletter states, 2022 should be a year of “focusing on the things that are most meaningful to you.” From meeting new people, visiting family, and doing what I love, I will further shift my focus to me, myself, and I.

— Lara, Cary High School

“Compassion”

Not just compassion towards others, but compassion to myself. During the last few years- especially with Covid and quarantines- I have struggled to find self-love while isolated from the people who love me most. And although school is in session, isolation is over, and I can see friends each day, that feeling of self-love isn’t always around. This is why my 2022 word is “compassion.” I want to learn how to be compassionate to myself and help anyone else who may feel similarly…That is what my year will be about. I will strive to be understanding, fair, and compassionate to myself, as well as to those I care about most.

— Anonymous, Glenbard West High School

“Monophobia”

My word means the fear of being alone. I choose this word because during 2021, life was very lonely and none of my friends were around. I want to fix that and make 2022 less lonely than 2021.

— Makayla, Mission San Jose High

Every single one of us went through a lot these past two years during lockdown like having mental health problems, physical health problems or financial problems, but we couldn’t do anything about it because of lockdown and all of us were silenced. We were silenced because even if we wanted to find a solution, there wasn’t any. Our mental health everyday was getting worse because we couldn’t go outside and we had minimal to no communication with others, we were silenced. Our physical health was being compromised because we couldn’t go outside to exercise and see the sun and we couldn’t feel better, we were silenced. Our financial problems were increasing because many people had lost their jobs and the economy was subsiding, and yet we were silenced.

These past two years have been nothing but silence, but with 2022 we should break that with sound. Sound can be the solution to our problems that we’ve faced through these past two years. We can break that silence with sound when we go outside, communicate with others, and we have opportunities to get jobs. We, together, can break the silence that we’ve faced with sound.

— Hana, Mission San Jose High School

Learn more about Current Events Conversation here and find all of our posts in this column .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Overcome a Fear of Rejection

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Stavros Constantinou / Getty Images

How to Overcome Fear of Rejection

- Common Behaviors

Psychological Outcomes

Frequently asked questions.

The fear of rejection is a powerful feeling that often has a far-reaching impact on our lives. Most people experience some nerves when placing themselves in situations that could lead to rejection, but for some people, the fear becomes overwhelming.

This fear can have many underlying causes. An untreated fear of rejection may worsen over time, leading to greater and greater limitations in a person's life.

This article discusses how to overcome your fear of rejection, and also how rejection sensitivity can affect your life and behavior.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

If you are experiencing a fear of rejection, there are steps you can take to learn how to cope better and stop this fear from negatively impacting your life. You may find the following strategies helpful for learning how to overcome a fear of rejection.

Improve Your Self-Regulation Skills

Self-regulation refers to your ability to identify and control your emotions and behaviors. It also plays an important role in overcoming your fear of rejection. By identifying negative thoughts that contribute to feelings of fear, you can actively take steps to reframe your thinking in a way that is more optimistic and encouraging.

Face Your Fears

Avoidance coping involves managing unpleasant feelings by simply avoiding the things that trigger those emotions. The problem with this approach is that it ultimately contributes to increased feelings of fear. Instead of getting better at dealing with your fear of rejection, it makes you even more fearful and sensitive to it.

So instead of avoiding situations where you might experience rejection, focus on putting yourself out there and tackling your fear. Once you have more experience facing your fear , you'll begin to recognize that the consequences are less anxiety-provoking than you anticipated. You'll also gain greater confidence in your own abilities to succeed.

Cultivate Resilience

Being resilient means that you are able to pick yourself up after a setback and move forward with a renewed sense of strength and optimism. Strategies that can help foster a greater sense of resilience include building your confidence in your own abilities, having a strong social support system, and nurturing and caring for yourself. Having goals and taking steps to improve your skills can also give you faith in your ability to bounce back from rejection.

Taking steps to overcome your fear of rejection can help minimize its detrimental impact on your life. Learning how to manage your emotions, taking steps to face your fears, and cultivating a strong sense of resilience can all help you become better able to tolerate the fear of rejection.

Where It Can Impact Your Life

Although not every person experiences the fear of rejection in the same way, it tends to affect the ability to succeed in a wide range of personal and professional situations.

Job Interviews

Fear of rejection can lead to physical symptoms that can sometimes be interpreted as a lack of confidence. Confidence and an air of authority are critical in many positions, and those experiencing this fear often come across as weak and insecure. If you have a fear of rejection, you may also have trouble negotiating work-related contracts, leaving valuable pay and benefits on the table.

Business Dealings

In many positions, the need to impress does not end once you have the job. Entertaining clients, negotiating deals, selling products, and attracting investors are key components of many jobs. Even something as simple as answering the telephone can be terrifying for people with a fear of rejection.

Meeting New People

Humans are social creatures, and we are expected to follow basic social niceties in public. If you have a fear of rejection, you may feel unable to chat with strangers or even friends of friends. The tendency to keep to yourself could potentially prevent you from making lasting connections with others.

First dates can be daunting, but those with a fear of rejection may experience significant anxiety. Rather than focusing on getting to know the other person and deciding whether you would like a second date, you might spend all of your time worrying about whether that person likes you. Trouble speaking, obsessive worrying about your appearance, an inability to eat, and a visibly nervous demeanor are common.

Peer Relationships

The need to belong is a basic human condition, so people often behave in ways that help them fit in with the group. While dressing, speaking, and behaving as a group member is not necessarily unhealthy, peer pressure sometimes goes too far. It could lead you to do things you're not comfortable with just to remain part of the group.

The fear of rejection can affect many different areas of life, including your success in the workplace and your relationships with friends and romantic partners.

How It Affects Your Behavior

When you have a fear of rejection, you may engage in behaviors focused on either covering up or compensating for this fear.

Lack of Authenticity

Many people who are afraid of rejection develop a carefully monitored and scripted way of life. Fearing that you will be rejected if you show your true self to the world, you may live life behind a mask. This can make you seem phony and inauthentic to others and may cause a rigid unwillingness to embrace life’s challenges.

People-Pleasing

Although it is natural to want to take care of those we love, those who fear rejection often go too far. You might find it impossible to say no, even when saying yes causes major inconveniences or hardships in your own life.

If you are a people-pleaser , you may take on too much, increasing your risk for burnout . At the extreme, people-pleasing sometimes turns into enabling the bad behaviors of others.

People with a fear of rejection often go out of their way to avoid confrontations. You might refuse to ask for what you want or speak up for what you need. A common tendency is to try to simply shut down your own needs or pretend that they don’t matter.

The fear of rejection may stop you from reaching your full potential. Putting yourself out there is frightening for anyone, but if you have a fear of rejection, you may feel paralyzed. Hanging onto the status quo feels safe, even if you are not happy with your current situation.

Passive-Aggressiveness

Uncomfortable showing off their true selves but unable to entirely shut out their own needs, many people who fear rejection end up behaving in passive-aggressive ways . You might procrastinate, "forget" to keep promises, complain, and work inefficiently on the projects that you take on.

The fear of rejection might drive you to engage in behaviors like passive-aggressiveness, passivity, and people-pleasing. It can also undermine your authenticity and make it difficult to be yourself when you are around others.

The fear of rejection leads to behaviors that make us appear insecure, ineffectual and overwhelmed. You might sweat, shake, fidget, avoid eye contact, and even lose the ability to effectively communicate. While individuals react to these behaviors in very different ways, these are some of the reactions you might see.

Ironically, the fear of rejection often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. It is well-known in pop psychology that confidence enhances attractiveness. As a general rule, the lack of self-confidence that is inherent in a fear of rejection makes us more likely to be rejected.

Research shows that confidence is nearly as important as intelligence in determining our income level.

Manipulation

Some people prey on the insecurities of others. Those who suffer from a fear of rejection may be at greater risk of being manipulated for someone else’s personal gain.

Expert manipulators generally come across as charming, suave, and caring—they know what buttons to push to make others trust them. They also know how to keep someone with a fear of rejection feeling slightly on edge, as if the manipulator might leave at any time. Almost invariably, the manipulator does end up leaving once they have gotten what they want out of the other person.

Frustration

Most people are decent, honest, and forthright. Rather than manipulating someone with a fear of rejection, they will try to help. Look for signs that your friends and family are trying to encourage your assertiveness, asking you to be more open with them, or probing your true feelings.

Many times, however, people who fear rejection experience these efforts as emotionally threatening. This often leads friends and family to walk on eggshells , fearful of making your fears worse. Over time, they may become frustrated and angry, either confronting you about your behavior or beginning to distance themselves from you.

A Word From Verywell

If you find that fear of rejection is negatively affecting your life and causing distress, it may be time to seek out psychotherapy . This can help you explore and better understand some of the underlying contributions to your fear and find more effective ways to cope with this vulnerability.

Past experiences with rejection can play a role in this fear. People who experience greater levels of anxiety or who struggle with feelings of loneliness , depression, self-criticism, and poor self-esteem may also be more susceptible.

Talking to people can be challenging if you have a fear of rejection. The best way to deal with it is to practice talking to others regularly. Remind yourself that everyone struggles with these fears sometimes and every conversation is a learning opportunity that improves your skills and confidence.

Some signs that you fear rejection include constantly worrying about what other people think, reading too much into what others are saying, going out of your way to please others, and avoiding situations where you might be rejected. You might also avoid sharing your thoughts and opinions because you fear that others might disagree with you.

Fear of rejection might be related to mental health conditions such as anxiety or depression. If your fear is affecting your ability to function normally and is creating distress, you should talk to your healthcare provider or a mental health professional.

Ding X, Ooi LL, Coplan RJ, Zhang W, Yao W. Longitudinal relations between rejection sensitivity and adjustment in Chinese children: moderating effect of emotion regulation . J Genet Psychol . 2021;182(6):422-434. doi:10.1080/00221325.2021.1945998

Ury W. Getting to Yes With Yourself and Other Worthy Opponents . HarperOne.

Epley N, Schroeder J. Mistakenly seeking solitude . J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(5):1980-99. doi:10.1037/a0037323

Houghton K. And Then I’ll Be Happy! Stop Sabotaging Your Happiness and Put Your Own Life First . Globe Pequot Press.

Potts C, Potts S. Assertiveness: How to Be Strong in Every Situation . Capstone.

Brandt A. 8 Keys to Eliminating Passive-Aggressiveness: Strategies for Transforming Your Relationships for Greater Authenticity and Joy . W.W. Norton & Company.

Leary MR. Emotional responses to interpersonal rejection . Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(4):435-41.

Judge TA, Hurst C, Simon LS. Does it pay to be smart, attractive, or confident (or all three)? Relationships among general mental ability, physical attractiveness, core self-evaluations, and income . J Appl Psychol . 2009;94(3):742-55. doi:10.1037/a0015497

Hopper E. Can helping others help you find meaning in life? . Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th Ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

By Lisa Fritscher Lisa Fritscher is a freelance writer and editor with a deep interest in phobias and other mental health topics.

A Psychology Professor Explains The Best Way To Deal With Rejection

Psychologist mark leary deconstructs the pain we feel when we experience rejection and how to feel better about it..

By Mark Travers, Ph.D. | April 18, 2022

A new study published in Advances In Motivation Science examines the root causes behind the pain of rejection and our relentless pursuit to be accepted by other people .

I recently spoke to psychologist Mark Leary, a former faculty member at Duke University and co-author of the new research, to understand how our value fluctuates depending on our need to belong. Here is a summary of our conversation.

What inspired you to investigate the topic of acceptance and belonging and how did you study it?

My original interest in graduate school involved self-presentation — how people's behavior and emotions are affected by their concerns with others' impressions of them. After studying self-presentation for several years, it dawned on me that, although people manage their impressions for many practical reasons, such as to get a job or repair an embarrassing event, one primary reason that people are concerned with what others think of them is that they want to be accepted and belong to groups.

Making "bad" impressions on other people lowers the likelihood that we will be accepted, develop friendships and romantic relationships , be valued as a group member, and obtain other social rewards.

This realization led me to pivot toward studying how people seek social acceptance and belonging and the impact of acceptance and rejection on people's emotions, behaviors, and views of themselves. Over the past 30 years, we have conducted dozens of research studies that dealt in one way or another with acceptance and rejection, using several research methodologies.

For example, we have conducted controlled laboratory experiments in which we led participants to feel accepted or rejected and measured their responses. We also used questionnaires to ask people about their personal experiences with rejection, and we have studied personality variables that are related to differences in how people seek acceptance and react to rejection.

What sorts of things did you find in this research?

Let me mention just two things that consumed a good deal of our attention after we accidentally stumbled on them.

Being rejected obviously evokes strong negative emotions. However, as we studied emotional reactions to rejection, we realized that researchers had more-or-less overlooked a very important response to rejection: the emotion that we commonly call "hurt feelings."

After conducting several studies of hurt feelings, we concluded that, in fact, hurt feelings is the primary emotional response to rejection, the emotion that occurs most reliably when people feel rejected.

Our research showed that people's feelings are hurt by six primary kinds of events:

- Active disassociation (for example, a romantic breakup)

- Passive disassociation (not being included)

- Being unappreciated

- Being teased

All of these are events that make people feel rejected. Put simply, hurt feelings are the "rejection emotion."

Of course, people who are rejected often have other emotions as well, such as sadness , anxiety , and anger .

Our research showed that these emotions are not reactions to rejection itself but rather to the nature or implications of the rejecting event. For example, rejections that produce a sense of loss cause sadness, rejections that include a threat to well-being or uncertainty about the future cause anxiety, and rejections that are viewed as unjustified cause anger. Only hurt feelings are caused by perceived rejection itself.

A second set of unexpected findings involved self-esteem. As we studied reactions to acceptance and rejection, we found that rejection consistently lowered people's state self-esteem — how they felt about themselves at the moment.

Changes in self-esteem were so strongly and consistently associated with rejection that we concluded that self-esteem is part of the psychological system that monitors and responses to social feedback.

We proposed a new theory, sociometer theory, that suggested that state self-esteem is a subjective gauge of interpersonal acceptance and rejection, an internal reflection of others' feelings about the person.

Not only does state self-esteem reflect people's perceptions of the degree to which they have relational value to others, but increases and decreases in state self-esteem may calibrate people's interpersonal aspirations.

Acceptance increases self-esteem, emboldening people to be more socially confident, whereas rejection lowers self-esteem, leading people to be more socially cautious.

Taking this idea one step further suggests that, contrary to the popular view, people do not need or seek self-esteem for its own sake. Rather, people are motivated to behave in ways that increase acceptance and avoid rejection, and those behaviors are precisely those that raise self-esteem.

So, self-esteem is a psychological meter or gauge. Just as people don't put gas in their cars to simply make their fuel gauge move away from empty and toward full, people don't do things simply to make their self-esteem go up.

Can you briefly describe what makes a person accepted?

People feel accepted when they perceive that they have "relational value" to another person or group of people.

Other people value their relationships with us to varying degrees. Some people value their relationship with us very much, invest a great deal in their connection to us, and would be very distressed if the relationship ended. Other people value their relationship with us only moderately; they may like interacting with us but would be only mildly bothered if they never saw us again. Other people don't value having a relationship with us at all.

We experience "acceptance" when we think our relational value to other people is sufficiently high, but feel "rejected" when our relational value is not as high as we wish. Of course, we all know that some people naturally value us more than other people do, and not everyone values having a relationship with us. We feel rejected when we perceive that our relational value in a particular situation or to a particular person is not as high as we want it to be.

Importantly, people don't need to be actually rejected in order to have the subjective experience of rejection.

For example, people may feel rejected even when they know the other person accepts or even loves them if they believe that their relational value to the person is not as high as they wish at that moment. So our romantic partners can make us feel rejected and hurt our feelings in a particular situation even though we know that they accept and love us.

Your research talks about the far-reaching impact of acceptance and belonging motivation on human behavior. Can you expand a bit on the same? What behaviors did you analyze and what did you find?

In 1995, Roy Baumeister and I wrote an article in which we suggested that the desire for acceptance and belonging may be the most fundamental interpersonal motive — the motive that affects our social behavior more than any other motive. This doesn't mean that we are motivated to be accepted all of the time or by everybody we meet. But concerns with acceptance and belonging underlie a great deal of human behavior, motivating certain behaviors and constraining others.

After publication of this article, many researchers dove into how the motivation to be accepted and to belong affects people's behavior. This motive influences human behavior in many ways, but let mention just five important domains in which our behavior is affected by concerns with acceptance and belonging.

- First, everything people do to enhance their physical attractiveness is aimed toward increasing acceptance, whether that's daily grooming, getting a haircut, trying to lose weight, or cosmetic surgery.

- Likewise, almost everything people do to be liked is motivated by a desire for relational value and acceptance. Most conformity to group norms and social pressure is also motivated by a desire to belong. In order to be viewed as an acceptable, valuable group member, people must conform to basic group norms.

- Although many researchers have viewed achievement motivation as quite distinct from the motive to be accepted, in fact, a great deal of achievement-related behaviors are motivated by a desire to increase one's relational value and be accepted. Think of what would happen if achievement was met with criticism, devaluation, and rejection instead of praise and acceptance.

- Perhaps the most ongoing and pervasive effect of approval and belonging motivation is on all of the things we do to be viewed as a good friend, partner, employee, group member, or member of society. Interpersonal interactions and relationships are guided by social exchange rules regarding how the individuals are expected to treat one another. A number of such rules have been identified including reciprocity, honesty, fairness, dependability, cooperation , and some minimal level of concern for other people's needs.

- People obviously prefer to have connections with those who abide by social exchange rules because people who violate these rules are viewed as poor social exchange partners who might disadvantage other people. So, concerns with acceptance and belonging underlie a great deal of polite, civil, ethical, and prosocial behavior.

Note that I'm not saying that a desire for acceptance is the only reason people behave in ways that enhance their appearance, help them be liked, conform to group pressure, lead them to achieve, or follow social exchange rules. (Sometimes they do these things to manipulate or take advantage of other people, for example.) But a concern with acceptance and belonging appears to be the primary driver of these behaviors.

In this world of judgments, how do you advise people to start feeling more accepted in their own skin?

Although being accepted is exceptionally important for people's well-being, simply feeling accepted can create its own problems unless people's feelings of acceptance and rejection are accurately calibrated to their actual relational value to other people.

Like all monitoring systems, the psychological systems that monitor and respond to social cues work best when they provide reasonably accurate information about what other people think of us.

So, simply trying to feel more accepted in one's skin isn't necessarily helpful.

The problem, of course, is that it's very difficult to determine how valued and accepted you actually are. Other people usually don't provide explicit social feedback, and the social cues we use to infer what other people are thinking about us are often quite ambiguous. This leaves a great deal of room for people to either overestimate or underestimate their relational value in other people's eyes, both of which can create behavioral miscalculations and emotional problems.

To make matters worse, our research shows that people tend to underestimate their relational value, interpreting relatively neutral social feedback as if it is rejecting.

For example, we tend to have negative, rather than neutral, reactions to learning that someone feels neutral about us. What this means is that most people probably go through life feeling more rejected than they actually are.

And, a history of actual rejection — by neglectful parents or rejecting peers, for example — seems to increase people's tendency to underestimate their relational value.

Viewed in this way, the first step in addressing one's concerns with acceptance and rejection is to examine the evidence as objectively as possible, trying not to either sugar-coat others' reactions or read too much negativity into them.

With that information in hand, we can bolster our feelings of acceptance in three ways:

- By learning to dismiss the negative reactions of people whose opinions of us really don't matter,

- Seeking connections with people to whom we would have higher relational value,

- Or, if needed, making changes in ourselves that might increase the degree to which other people value having connections with us.

How does this fear of judgments impact the psychological health of a person?

Excessive concerns about negative evaluations and possible rejection obviously undermine psychological well-being.

People who have a high fear of negative evaluation tend to score higher in social anxiety because social anxiety arises from the belief that one will not be perceived in ways that promote acceptance.

Fear of negative evaluation also makes people particularly vigilant to cues that might reflect rejection and to a tendency to give a worst-case reading to cues and feedback that might convey low relational value.

These concerns also lead to reticence and inhibition, to shyness, in an effort not to say or do things that might lower one's relational value further.

Can this have physical impacts as well?

Anything that increases anxiety and stress can certainly have undesired physical effects, so people who are excessively concerned with rejection have some sorts of problems as people with other ongoing sources of anxiety and stress, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal problems.

How can medical professionals like therapists and psychologists help in such cases?

When helping people deal with rejections, mental health professionals, as well as friends, parents, and others, can help the person work through a couple of issues.

First, is the person's perception of the situation accurate? Is his or her relational value as low as he or she thinks it is? If the answer is "no" — that is, the person is perceiving rejection where none exists — then steps can be taken to try to correct the misperception.

However, if the answer is "yes," the best response depends on the nature of the situation, the cause of the rejection, and whether the rejection was a one-time thing (a romantic breakup, for example) or an ongoing pattern of being excluded, ignored, or bullied by others.

We can help the person troubled by rejection understand the nature of the rejection and his or her role in it, then formulate a plan both to deal emotionally with the rejection and, if needed, to take practical steps to reduce the likelihood of similar events in the future.

Did something unexpected emerge from your research? Something beyond the hypothesis?

We certainly knew from the beginning that people are universally concerned with being accepted and react strongly when they experience rejection. What surprised me is how little it takes to make people feel relationally devalued and rejected.

In our experimental studies in which we led research participants to feel rejected, we obviously had to use very weak methods to induce rejection for ethical reasons. In almost all of these studies, the participants did not know one another and had no reason to think they would ever meet again.

In fact, in some studies, participants never saw one another or learned each others' identities, and they interacted over an intercom or by exchanging written answers on sheets of people. And the nature of the rejections was quite minor.

For example, participants were told that another participant preferred to work with another person rather than them on a laboratory task or received feedback that another participant had rated them as average rather than positively. Importantly, none of these minor "rejections" had any consequences on the participants' lives.

But even though these were seemingly meaningless rejections with no consequences whatsoever by people the participants didn't know and would never see again, we consistently got strong effects.

Participants who were rejected in our studies consistently experienced more negative emotions (hurt feelings, sadness, anxiety, and sometimes anger), showed a loss of state self-esteem and had very negative views of those who had rejected them.

Given that such trivial rejection experiences had such powerful effects, it's not surprising that concerns with rejection permeate our lives.

Why getting better about being rejected can help you succeed in life

Getting the thin instead of thick envelope from the college admissions office. Picked last for the kickball team. Being told, “let’s just be friends.”

Rejection hurts no matter if it’s the big kind (not getting that job that was so right for you) or less significant ( getting turned down by a Tinder match ).

Our feelings are hurt, our self-esteem takes a hit, and it unsettles our feeling of belonging, says Guy Winch, PhD , psychologist and author of " Emotional First Aid: Healing Rejection, Guilt, Failure, and Other Everyday Hurts ". “Even very mild rejection can really sting,” he tells NBC News BETTER.

But there are ways we can handle it, so that the fear of rejection doesn’t stop us from putting ourselves out there.

“Concern with rejection is perfectly normal,” explains Mark R. Leary, PhD , professor of psychology and neuroscience at the Interdisciplinary Behavioral Research Center at Duke University, where he researches human emotions and social motivations. “But being excessively worried about it — to the point that we do not do things that might benefit us — can compromise the quality of our life,” Leary says.

Rejection actually fires up a pain response in the brain

Leary defines rejection as when we perceive our relational value (how much others value their relationship with us) drops below some desired threshold. What makes the bite in rejection so particularly gnarly may be because it fires up some of the same pain signals in the brain that get involved when we stub our toe or throw out our back, Leary explains.

Research , for example, in which functional MRI scans compared brain activity in people who’d experienced rejection with brain activity in people who’d experienced physical pain, found that many of the same regions of the brain lit up (and those regions had previously been linked to physical pain).

Subsequent research found that the pain we feel from rejection is so akin to that we feel from physical pain that taking acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) after experiencing rejection actually reduced how much pain people reported feeling — and brain scans showed neural pain signaling was lessened, too.

The pain we feel from rejection is part of what’s helped humans survive

Psychologists suspect all of this hurt is likely a relic of our evolutionary past — and something that’s helped mankind survive for millennia.

The physical pain you feel when you grab the handle of a pot of boiling water, is a signal to tell you to let go (so you don’t continue to burn your hand). Similarly, the sting of rejection sends a signal that something is wrong in terms of your social wellbeing, Leary says. In prehistoric times, social rejection could have had dire consequences.

“When our prehistoric ancestors lived in small nomadic bands on the plains of Africa, being rejected from the clan would have been a death sentence,” Leary explains. “No one would have survived out there alone with just a sharp rock.”

Therefore the people who were more likely to be sensitive to rejection and more likely to take it as a signal to change their behavior before being shunned, would have been the ones who were more likely to survive and reproduce.

So, we exist today, thousands of years later, as descendants of those prehuman “cool kids” — the ones who were more successful at being valued and accepted (because the kids who didn’t have anyone to eat lunch with wouldn’t have made it).

So even today, Leary says, “rejection gets our attention and forces us to consider our social circumstances.”

It’s the likely explanation as to why we tend to feel more stung by rejection, even, than by failure, Winch adds. Failure is very task-specific (we don’t complete a goal or achieve something) , whereas there’s an interpersonal dynamic to rejection, he says.

'Forget Willpower' Why planning for failure can help you reach your goals

When it comes to better dealing with rejection, you’re going to have to turn off autopilot mode.

The problem is that we tend to face more opportunities to be rejected than ever before in human history (thanks to technology like social media and the Internet). And even though there’s still an interpersonal dynamic, most of the online and real-life rejections most of us face today don’t threaten our survival so much as they did thousands of years ago, Leary says.

The problem is that we tend to face more opportunities to be rejected than ever before in human history (thanks to technology like the social media and the Internet).

But, we’re still wired to react as though they do. “Our brains don’t easily tell the difference between rejections that matter and those that don’t unless we consciously think about it and override our automatic reactions,” Leary says.

You override that response by recognizing when the hurt we’re feeling is rejection, and better responding to the inevitable hurt we feel. “It’s up to us — how we respond and how we handle it in our heads and in our actions,” Winch explains.

Taking these steps can help:

1. Focus on what you do bring to the table

Because most rejection won’t leave you doomed to survive alone in the wilderness, the natural rejection reaction — to withdraw and not put ourselves out there again — isn’t an adaptive response, Winch says. Instead make efforts to revive self-esteem, focus on our positive qualities, and remember why our attributes might be appreciated by someone else in a different situation. All of those things build resilience, so you’ll be better prepared to cope going ahead, he says.

2. Ask yourself if it really matters or you really care

“Responses to rejection are often automatic, even when it doesn’t matter,” Leary says. Research shows we tend to feel a similar hurt after getting rejected by people we don’t necessarily care about — or even those we don’t like — as we do after being rejected by people who matter to us. (One study found that even when the group doing the rejecting was a reviled one — in this case the Klu Klux Klan — rejection still hurt.)

We need to get better at distinguishing whose rejection matters to us (whose we should care about, like that by family or a close friend) versus the inconsequential kind, Leary says.

3. Remember, a lot of times rejection isn’t personal

Most of the rejections we face aren’t personal, Winch says. You didn’t get the job because someone else had previously known and worked with the team, not because you weren’t good enough. Your friend didn’t “like” your Instagram post because she didn’t see it — or didn’t have a free finger to click that button.

Sometimes rejection can be personal, Winch says. “But a lot of times it’s not.”

4. Choose to assume the best rather than the worst

We need to train ourselves to make allowances, rather than assume the worst. Maybe he didn’t text for a second date because he got a job offer out of state or his on-again-off-again ex got back in touch. Maybe it had nothing to do with not liking you.

We oftentimes have no idea what’s going on on the other side of the situation, Winch says. And to be more resilient, we need to sometimes choose the assumption that’s less painful and less hurtful.

5. And do get back out there

The “don’t pay attention to what other people think” lecture parents give when a kid doesn’t get invited to the popular kid's party in middle school doesn’t really help, Winch says. “Now you’re not only feeling bad, you’re now feeling like a major loser for feeling bad.”

Planning something else with friends goes much farther to reinforce you you’re not actually a loser — and you are part of your tribe. We need to reteach ourselves and those around us to get back out there after rejection (whether it’s applying for other jobs or not taking a dating hiatus). Withdrawing doesn’t help the overall goal, Winch says.

MORE FROM BETTER

- How to manage stress so that it doesn't hurt your health

- Stressed? Here's how to tap into a zen feeling (almost) instantly

- How to bounce back from 'headline stress disorder'

- Why the simple act of being in nature helps you de-stress

Want more tips like these? NBC News BETTER is obsessed with finding easier, healthier and smarter ways to live. Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Everyone Gets Rejected — Here’s How to Move On

Resilience is the key to your success.

The key to achieving your career ambitions comes down to one question: How many times are you willing to pick yourself up after falling down?

- The rate at which you achieve your goals is always going to be a combination of volume, probability, timing, luck, and resilience. In other words, you need to be resilient in the face of rejection.

- The next time you face a setback try using an exercise, titled G.R.O.W., to overcome it.

- Ground yourself in the situation; recognize what you can control; organize your resources; work with your community for support.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Rejection sucks. Always has, always will.

- Raj Tawney is a freelance writer in New York . He’s currently working on a memoir about his multiracial American identity.

Partner Center

Afraid of Being Rejected?

Fear of failure or rejection.

Posted October 19, 2009

One of the central problems for you if you are anxious is your fear of making a mistake and your fear of being rejected. I don't know about you, but I sure have a long history of rejection---only because, I think, I have constantly been trying to be productive. When I was single I was rejected by girlfriends-but accepted by some. I have had book proposals and articles rejected. I view rejection as part of the cost of playing the game. You won't be able to win unless you can tolerate losing some.

If you wonder if other people have made mistakes, here is a list of authors and books that have been rejected by publishers when first submitted. The authors include James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, Sylvia Plath, Jack Kerouac, Jorge Luis Borges, Isaac Bashevis Singer (who won the Nobel Prize), Marcel Proust, Stephen King, Oscar Wilde, and George Orwell. Famous books that have been rejected include The Diary of Anne Frank, War and Peace, The Good Earth, Gone with the Wind, Dr. Seuss, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, Watership Down, Lolita, Angela's Ashes, Harry Potter and The Hobbitt. The editor who rejected the classic book, Animal Farm, by George Orwell had this piece of wisdom : ‘It is impossible to sell animal stories in the USA'. Another brilliant observation-and a classic mistake- was the following: "Everything that can be invented has been invented", claimed the forgettable Charles Duell, Commissioner of the US Patent Office in 1899. Or consider this: "I think there is a world market for maybe five computers."(Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943). Or, one of my favorites: "We don't like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out" by Decca Recording Company when they rejected the Beatles in 1962.

Well, it's not just publishers and business people who make mistakes-we all do. Here's how you can find out. Ask every one of your friends about mistakes that they have made. If they are honest, they will reveal some great stories.

Mistakes are the pathway to success---if you persist and learn from them.

Robert L. Leahy, Ph.D. , is the author of The Jealousy Cure, Anxiety Free, The Worry Cure , and Beat the Blues . He is a clinical professor of psychology at Weill-Cornell Medical School.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Joan Didion Essay About Being Rejected by Her Top College

- February 23, 2021

David Bersell

By Joan Didion

This piece, about the author’s college rejection from her first-choice college, appeared in The Saturday Evening Post April 16, 1968.