866.342.1813 | Email Us

27 Jul Integration vs. Inclusion

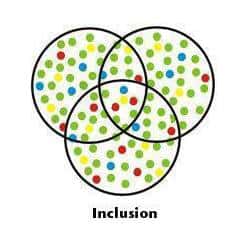

Are you familiar with the difference between integration and inclusion when it comes to the classroom environment? The trend in education today is moving away from integration and toward inclusion. While both approaches aim to bring students with disabilities into the mainstream classroom, one system expects students to adapt to the pre-existing structure, while the other ensures the existing education system will adapt to each student.

An integrated classroom is a setting where students with disabilities learn alongside peers without disabilities. Extra supports may be implemented to help them adapt to the regular curriculum, and sometimes separate special education programs are in place within the classroom or through pull-out services. In theory, integration is a positive approach that seeks to help students with disabilities be part of the larger group. In practicality, the differences in the way all people learn can make this system of education less effective overall.

Following guidelines for accessibility makes an inclusive classroom possible. Bridgeway Education can support you in your transition to an accessible curriculum. Contact us for a free accessibility evaluation of a sample of your content, or sign up for The Accessibility Imperative professional development course to learn about creating accessible learning experiences for all students.

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, inclusive education: what it means, proven strategies, and a case study.

Considering the potential of inclusive education at your school? Perhaps you are currently working in an inclusive classroom and looking for effective strategies. Lean into this deep-dive article on inclusive education to gather a solid understanding of what it means, what the research shows, and proven strategies that bring out the benefits for everyone.

What is inclusive education? What does it mean?

Inclusive education is when all students, regardless of any challenges they may have, are placed in age-appropriate general education classes that are in their own neighborhood schools to receive high-quality instruction, interventions, and supports that enable them to meet success in the core curriculum (Bui, Quirk, Almazan, & Valenti, 2010; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

The school and classroom operate on the premise that students with disabilities are as fundamentally competent as students without disabilities. Therefore, all students can be full participants in their classrooms and in the local school community. Much of the movement is related to legislation that students receive their education in the least restrictive environment (LRE). This means they are with their peers without disabilities to the maximum degree possible, with general education the placement of first choice for all students (Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

Successful inclusive education happens primarily through accepting, understanding, and attending to student differences and diversity, which can include physical, cognitive, academic, social, and emotional. This is not to say that students never need to spend time out of regular education classes, because sometimes they do for a very particular purpose — for instance, for speech or occupational therapy. But the goal is this should be the exception.

The driving principle is to make all students feel welcomed, appropriately challenged, and supported in their efforts. It’s also critically important that the adults are supported, too. This includes the regular education teacher and the special education teacher , as well as all other staff and faculty who are key stakeholders — and that also includes parents.

The research basis for inclusive education

Inclusive education and inclusive classrooms are gaining steam because there is so much research-based evidence around the benefits. Take a look.

Benefits for students

Simply put, both students with and without disabilities learn more . Many studies over the past three decades have found that students with disabilities have higher achievement and improved skills through inclusive education, and their peers without challenges benefit, too (Bui, et al., 2010; Dupuis, Barclay, Holms, Platt, Shaha, & Lewis, 2006; Newman, 2006; Alquraini & Gut, 2012).

For students with disabilities ( SWD ), this includes academic gains in literacy (reading and writing), math, and social studies — both in grades and on standardized tests — better communication skills, and improved social skills and more friendships. More time in the general classroom for SWD is also associated with fewer absences and referrals for disruptive behavior. This could be related to findings about attitude — they have a higher self-concept, they like school and their teachers more, and are more motivated around working and learning.

Their peers without disabilities also show more positive attitudes in these same areas when in inclusive classrooms. They make greater academic gains in reading and math. Research shows the presence of SWD gives non-SWD new kinds of learning opportunities. One of these is when they serve as peer-coaches. By learning how to help another student, their own performance improves. Another is that as teachers take into greater consideration their diverse SWD learners, they provide instruction in a wider range of learning modalities (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic), which benefits their regular ed students as well.

Researchers often explore concerns and potential pitfalls that might make instruction less effective in inclusion classrooms (Bui et al., 2010; Dupois et al., 2006). But findings show this is not the case. Neither instructional time nor how much time students are engaged differs between inclusive and non-inclusive classrooms. In fact, in many instances, regular ed students report little to no awareness that there even are students with disabilities in their classes. When they are aware, they demonstrate more acceptance and tolerance for SWD when they all experience an inclusive education together.

Parent’s feelings and attitudes

Parents, of course, have a big part to play. A comprehensive review of the literature (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2010) found that on average, parents are somewhat uncertain if inclusion is a good option for their SWD . On the upside, the more experience with inclusive education they had, the more positive parents of SWD were about it. Additionally, parents of regular ed students held a decidedly positive attitude toward inclusive education.

Now that we’ve seen the research highlights on outcomes, let’s take a look at strategies to put inclusive education in practice.

Inclusive classroom strategies

There is a definite need for teachers to be supported in implementing an inclusive classroom. A rigorous literature review of studies found most teachers had either neutral or negative attitudes about inclusive education (de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, 2011). It turns out that much of this is because they do not feel they are very knowledgeable, competent, or confident about how to educate SWD .

However, similar to parents, teachers with more experience — and, in the case of teachers, more training with inclusive education — were significantly more positive about it. Evidence supports that to be effective, teachers need an understanding of best practices in teaching and of adapted instruction for SWD ; but positive attitudes toward inclusion are also among the most important for creating an inclusive classroom that works (Savage & Erten, 2015).

Of course, a modest blog article like this is only going to give the highlights of what have been found to be effective inclusive strategies. For there to be true long-term success necessitates formal training. To give you an idea though, here are strategies recommended by several research studies and applied experience (Morningstar, Shogren, Lee, & Born, 2015; Alquraini, & Gut, 2012).

Use a variety of instructional formats

Start with whole-group instruction and transition to flexible groupings which could be small groups, stations/centers, and paired learning. With regard to the whole group, using technology such as interactive whiteboards is related to high student engagement. Regarding flexible groupings: for younger students, these are often teacher-led but for older students, they can be student-led with teacher monitoring. Peer-supported learning can be very effective and engaging and take the form of pair-work, cooperative grouping, peer tutoring, and student-led demonstrations.

Ensure access to academic curricular content

All students need the opportunity to have learning experiences in line with the same learning goals. This will necessitate thinking about what supports individual SWDs need, but overall strategies are making sure all students hear instructions, that they do indeed start activities, that all students participate in large group instruction, and that students transition in and out of the classroom at the same time. For this latter point, not only will it keep students on track with the lessons, their non-SWD peers do not see them leaving or entering in the middle of lessons, which can really highlight their differences.

Apply universal design for learning

These are methods that are varied and that support many learners’ needs. They include multiple ways of representing content to students and for students to represent learning back, such as modeling, images, objectives and manipulatives, graphic organizers, oral and written responses, and technology. These can also be adapted as modifications for SWDs where they have large print, use headphones, are allowed to have a peer write their dictated response, draw a picture instead, use calculators, or just have extra time. Think too about the power of project-based and inquiry learning where students individually or collectively investigate an experience.

Now let’s put it all together by looking at how a regular education teacher addresses the challenge and succeeds in using inclusive education in her classroom.

A case study of inclusive practices in schools and classes

Mrs. Brown has been teaching for several years now and is both excited and a little nervous about her school’s decision to implement inclusive education. Over the years she has had several special education students in her class but they either got pulled out for time with specialists or just joined for activities like art, music, P.E., lunch, and sometimes for selected academics.

She has always found this method a bit disjointed and has wanted to be much more involved in educating these students and finding ways they can take part more fully in her classroom. She knows she needs guidance in designing and implementing her inclusive classroom, but she’s ready for the challenge and looking forward to seeing the many benefits she’s been reading and hearing about for the children, their families, their peers, herself, and the school as a whole.

During the month before school starts, Mrs. Brown meets with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez — and other teachers and staff who work with her students — to coordinate the instructional plan that is based on the IEPs (Individual Educational Plan) of the three students with disabilities who will be in her class the upcoming year.

About two weeks before school starts, she invites each of the three children and their families to come into the classroom for individual tours and get-to-know-you sessions with both herself and the special education teacher. She makes sure to provide information about back-to-school night and extends a personal invitation to them to attend so they can meet the other families and children. She feels very good about how this is coming together and how excited and happy the children and their families are feeling. One student really summed it up when he told her, “You and I are going to have a great year!”

The school district and the principal have sent out communications to all the parents about the move to inclusion education at Mrs. Brown’s school. Now she wants to make sure she really communicates effectively with the parents, especially as some of the parents of both SWD and regular ed students have expressed hesitation that having their child in an inclusive classroom would work.

She talks to the administration and other teachers and, with their okay, sends out a joint communication after about two months into the school year with some questions provided by the book Creating Inclusive Classrooms (Salend, 2001 referenced in Salend & Garrick-Duhaney, 2001) such as, “How has being in an inclusion classroom affected your child academically, socially, and behaviorally? Please describe any benefits or negative consequences you have observed in your child. What factors led to these changes?” and “How has your child’s placement in an inclusion classroom affected you? Please describe any benefits or any negative consequences for you.” and “What additional information would you like to have about inclusion and your child’s class?” She plans to look for trends and prepare a communication that she will share with parents. She also plans to send out a questionnaire with different questions every couple of months throughout the school year.

Since she found out about the move to an inclusive education approach at her school, Mrs. Brown has been working closely with the special education teacher, Mr. Lopez, and reading a great deal about the benefits and the challenges. Determined to be successful, she is especially focused on effective inclusive classroom strategies.

Her hard work is paying off. Her mid-year and end-of-year results are very positive. The SWDs are meeting their IEP goals. Her regular ed students are excelling. A spirit of collaboration and positive energy pervades her classroom and she feels this in the whole school as they practice inclusive education. The children are happy and proud of their accomplishments. The principal regularly compliments her. The parents are positive, relaxed, and supportive.

Mrs. Brown knows she has more to learn and do, but her confidence and satisfaction are high. She is especially delighted that she has been selected to be a part of her district’s team to train other regular education teachers about inclusive education and classrooms.

The future is very bright indeed for this approach. The evidence is mounting that inclusive education and classrooms are able to not only meet the requirements of LRE for students with disabilities, but to benefit regular education students as well. We see that with exposure both parents and teachers become more positive. Training and support allow regular education teachers to implement inclusive education with ease and success. All around it’s a win-win!

Lilla Dale McManis, MEd, PhD has a BS in child development, an MEd in special education, and a PhD in educational psychology. She was a K-12 public school special education teacher for many years and has worked at universities, state agencies, and in industry teaching prospective teachers, conducting research and evaluation with at-risk populations, and designing educational technology. Currently, she is President of Parent in the Know where she works with families in need and also does business consulting.

You may also like to read

- Inclusive Education for Special Needs Students

- Teaching Strategies in Early Childhood Education and Pre-K

- Mainstreaming Special Education in the Classroom

- Five Reasons to Study Early Childhood Education

- Effective Teaching Strategies for Special Education

- 6 Strategies for Teaching Special Education Classes

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Curriculum and Instruction , High School (Grades: 9-12) , Middle School (Grades: 6-8) , Pros and Cons , Teacher-Parent Relationships , The Inclusive Classroom

- Online Education Specialist Degree for Teache...

- Online Associate's Degree Programs in Educati...

- Master's in Math and Science Education

Inclusion in education

UNESCO believes that every learner matters equally. Yet millions of people worldwide continue to be excluded from education for reasons which might include gender, sexual orientation, ethnic or social origin, language, religion, nationality, economic condition or ability. Inclusive education works to identify all barriers to education and remove them and covers everything from curricula to pedagogy and teaching. UNESCO’s work in this area is firstly guided by the UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) as well as Sustainable Development Goal 4 and the Education 2030 Framework for Action which emphasize inclusion and equity as the foundation for quality education.

What you need to know about inclusion in education

Global Education Monitoring Report 2020

Resource base on inclusive education

face exclusion from education on a daily basis

live with a disability globally

do not have minimum requirements for water, sanitation and hygiene

at the end of primary education if they learn in their mother tongue

Monitoring SDG 4: inclusion in education

Resources from UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report.

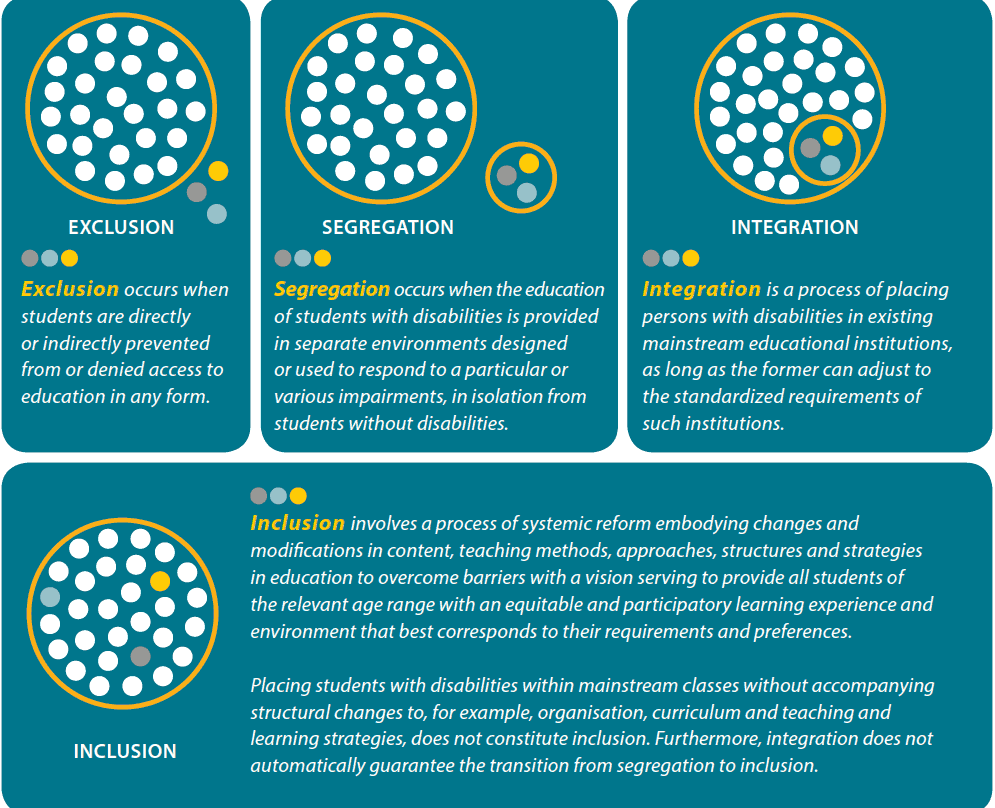

Inclusion, Exclusion, Segregation, and Integration: How are they different?

The power of social media.

During the early days of Think Inclusive, we posted a photo that demonstrated the differences between inclusion, exclusion, segregation, and integration. The post went viral.

Various Interpretations

It is still unclear who originally created the image. Although it garnered a lot of attention, its meaning was open to interpretation, leading to various reactions from different people. Some people perceived the images of inclusion and integration as being regressive, while others interpreted the different colors as representing various races. Additionally, some individuals modified and edited the photo to suit their own perspectives, with some being humorous and others more serious. Here are some examples of these interpretations.

Guidance from the United Nations

So, what are the correct definitions of these images? Fortunately, we came across an astonishing visual from a document called A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education created by Abt Associates . They envisioned the original image in a much clearer way and included definitions from the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – General Comment No. 4 . We have added the image here and encourage you to read both documents referenced above.

The Committee highlights the importance of recognising the differences between exclusion, segregation, integration and inclusion. Exclusion occurs when students are directly or indirectly prevented from or denied access to education in any form. Segregation occurs when the education of students with disabilities is provided in separate environments designed or used to respond to a particular or various impairments, in isolation from students without disabilities. Integration is a process of placing persons with disabilities in existing mainstream educational institutions, as long as the former can adjust to the standardized requirements of such institutions. Inclusion involves a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. Placing students with disabilities within mainstream classes without accompanying structural changes to, for example, organisation, curriculum and teaching and learning strategies, does not constitute inclusion. Furthermore, integration does not automatically guarantee the transition from segregation to inclusion. A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education

According to the UN’s definitions, most school districts in the United States are practicing integration rather than the “systematic reform” and “structural changes” that inclusion encompasses. It is no wonder that people are confused when talking about the differences between inclusion and integration.

What do you think? Do you have different interpretations of inclusion, exclusion, segregation, and integration?

Tim Villegas is the Director of Communications for the Maryland Coalition for Inclusive Education. He is also the founder of Think Inclusive, which is the blog, podcast, and social media handle of MCIE. He has 16 years of experience in public education as a teacher and district support specialist. His focus now is on how media and communications can promote inclusive education for all learners.

What can we help you find?

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Teacher education and inclusivity.

- Sarah L. Alvarado , Sarah L. Alvarado Arizona State University

- Sarah M. Salinas Sarah M. Salinas Arizona State University

- and Alfredo J. Artiles Alfredo J. Artiles Arizona State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.278

- Published online: 28 August 2019

Inclusive teacher education (ITE) defines the professional training of preservice teachers to work in learning spaces encompassing students from all circumstances, regardless of race, linguistic background, gender, socioeconomic status, and special education needs (SEN). This preparation includes the content, pedagogy, and formative experiences required for teachers to work in inclusive schools.

To fully understand ITE, it is necessary to examine what is meant by inclusive education (IE). Indeed, it is essential to explore ITE’s definition since scholars and teacher educators have struggled to agree on what is meant by IE. In addition to disagreements about IE’s definition, support for this idea and its implementation may vary due to the cultural, historical, and political differences specific to local contexts. For these reasons, it is necessary to recognize the inclusive policies, practices, and processes that often shape definitions and concepts related to ITE.

Notwithstanding the ambitious meanings of ITE across the globe, researchers, professionals, and policymakers tend to emphasize a vision of teacher preparation for working with students with disabilities (SWD) or SEN. Also, there is no consensus about which particular aspects matter in teacher education programs, primarily based on ideological differences about the core goals of IE. These differences in views and beliefs have resulted in limited understandings and applications of ITE. For instance, a student with an SEN may also come from a family living in poverty, with no access to books in the home, or speak multiple languages, including languages that are not a part of their first (formal) educational experiences. In such circumstances, there is no agreement about whether ITE programs should focus on students’ linguistic, socioeconomic, learning differences, or multiple factors.

We review the research on ITE in various national contexts. We also discuss how scholars have conceptualized the preparation of future teachers and the implications for greater clarity on how teacher preparation can improve IE in an increasingly diverse society.

- inclusive teacher education

- disabilities

- inclusivity

- teacher preparation

- preservice teachers

The purpose of this article is to synthesize the fundamental concepts and core parameters that inform the preparation of teachers for inclusive education (IE) and summarize research on nclusive teacher education (ITE). We assume that ITE programs provide pre-service teachers with the content, pedagogy, and formative experiences to work in inclusive schools and lead inclusive classrooms. We begin by setting the context through a discussion of how scholars have conceptualized IE. Next, we outline the evolution of ITE across national contexts in the past several decades and briefly illustrate controversies and tensions associated with ITE. The core of the article presents an overview of research trends and selected examples of ITE to explain such patterns. We reviewed empirical studies and conceptual pieces based on empirical work published between 2005 and 2017 in peer-reviewed journals, handbooks, or book chapters. We recognize IE’s original intentions were grounded in equity-minded work and began decades before this period (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 ; Ryndak & Fisher, 1988 ), but we narrowed our scope to literature published in the last ten years particularly, after the reauthorization of special education law in the United States. Most of the chosen publications focused on the United States and the United Kingdom since these are the countries with sizable IE literature. However, we also included examples from other nations, such as Canada, Scandinavian countries, and Australia. We conclude with reflections for future scholarship.

Setting the Context

Ie definitions.

It is necessary to contextualize a review of the research on ITE with a brief discussion about IE. Artiles and Kozleski ( 2016 ) characterized IE literature as highly visible yet contentious. While IE has emphasized the physical placement of students in educational settings (Forlin, Loreman, Sharma, & Earle, 2009 ), we highlight IE’s varying definitions and assumptions about whom, where, and what types of inclusion and inclusive practices pre-service teachers might utilize (Booth, Nes, & Strømstad, 2003 ; Forlin, 2010a ). Thus, IE does not constitute a monolithic and even cohesive movement, as scholars have identified various discourses surrounding the conceptualization and evolution of this notion. For instance, the IE literature has focused on the justification for and the implementation of inclusion (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 ; Dyson, 1999 ). In turn, each of these discourses is grounded in alternative views of social justice and focus on different dimensions of the IE movement. This state of affairs contributes to the fragmentation of scholarship on IE and complicates the aggregation of insights and IE research findings.

Scholars have primarily founded arguments over IE’s definition on the physical placement of students with disabilities (SWD) in the general education classroom or as the transformation of educational systems (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 ). Arguments over “what counts as IE” (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 , p. 7) have evolved from mainstreaming to integration , followed by full inclusion . The implementation and progress of IE have been contested and has certainly varied by time and location, often having strong “local flavours” (Artiles & Dyson, 2005 , p. 37), based on how IE proponents or speculators define IE (Graham & Slee, 2008 ). Slee ( 2001 ) and others argued that the obscurity in IE’s definition reflects the robust missing conversation, often based on disagreements over IE’s overall purpose, challenging existing and past views of IE and preventing conversations from extending this discourse into new conceptual territories.

We reviewed the research base to illustrate how researchers have defined and conceptualized ITE. As such, we identified at least two viewpoints: (a) medically oriented IE approaches and (b) systemic IE approaches. An important question to bear in mind is if and how these conceptual perspectives permeate the scholarship on ITE. We return to this point in a subsequent section of this article.

Medical Model Approach

The medical model perspective generally equates IE with special education, which is rooted in the medical model of disability (Artiles, 2013 ). Although some researchers would argue this perspective should not be considered a form of IE, scholars acknowledge how the two terms (IE and special education) are often used interchangeably. To demonstrate this point, we look to Florian’s explanation of how and why these two terms are commonly used interchangeably, particularly in some areas of the world:

In the developing world, where universal access to primary education is not assured, separate special education provision may represent the only educational opportunity available to children with disabilities. Thus, although “special” and “inclusive” education are different concepts, particularly in many countries of the developed world where inclusive educating is seen a part of the larger diversity agenda, rather than a response to a particular group of learners, the terms are used synonymously in other countries. (Florian, 2014 , p. 54)

A core IE principle under the medical model is that correctly identifying a student’s deficit is crucial for the subsequent administration of proper interventions to support students’ learning (Trent, 1994 ). Moreover, the medical model relates to the belief that disabilities reside in the body or mind of the individual and that the principal goal of IE is to provide treatments and interventions that ameliorate, cure, or rehabilitate people’s deficits (Artiles, 2013 ; Trent, 1994 ). Booth and colleagues asserted this perspective as predominantly focused on the dilemma of differences between students with and without special education need (SEN) (Booth, Nes, & Strømstad, 2003 ).

ITE programs based on the medical model of disability prepare specialized educators to provide the treatments, interventions, and strategies that learners with disabilities or other special needs require to enhance students’ educational experiences and outcomes. These interventions may occur inside or outside general education settings. To this end, the ITE literature tends to use the terms general and special education (Allsopp & Haley, 2015 ). Special education services include programs delivered across a continuum of educational placement options ranging from general education classrooms for the entire (or parts of the) school day to special classes where teachers educate students for varying portions of the day.

Systemic IE

The systemic view of IE proposes that systems or institutions must change to serve the needs of students, rather than emphasizing students’ disabilities. In this way, IE is not a program nor a placement “but an approach embodying particular values” (Ainscow, Booth, & Dyson, 2006 , p. 301). Systemic views of IE support a transformative agenda in which school cultures are reconstructed to increase student access, participation, and achievement, as well as “enhanc[ing] school personnel’s and students’ acceptance of all students” (Artiles, Kozleski, Dorn, & Christensen, 2006 , p. 67). Systemic IE pushes beyond what needs to happen to individual students, by focusing on what society and systems can do to address the physical and social stigmas and conditions that create the disabling status and experiences for the individual. As such, it is not the individual’s need or use of a wheelchair that creates the disability; instead, it is the lack of wheelchair accessible buildings and classrooms that impact the inclusivity of the environment. From this view, IE is a “process rather than a destination,” (Mittler, 2000 , p. 12) mainly centered on the pedagogical stances that value diversity beyond specific disabilities. For instance, over the last decade, the discourse of IE is reflective of other emergent concerns and priorities, beyond individual learning differences. A systemic approach emphasizes the need to attend to systemic barriers that prevent youth and persons of all ages from their rights, protections, and access to an education regardless of their citizenship status, gender orientation, or other social markers without marginalization; education as a human right (Artiles, 2011 ). Basically, this perspective emphasizes the transformation of entire educational systems, including technical (e.g., curricula, pedagogy, assessment) and organizational dimensions (e.g., budgets, staffing, space allocation), with explicit attention to the sociocultural, historical, and ideological underpinnings of schooling in society.

Next, we turn to a brief historical overview of IE covering sociocultural and historical processes that have shaped and been shaped by inclusive agendas. Such sociocultural and historical factors, as we will exemplify, have, and continue to produce implications for ITE. We conclude with a discussion of the significant conceptual differences represented in the medical and systemic perspectives of IE, and how those varying inclusive perspectives continue to cause tensions. Besides, differences in conceptualization and implementation of IE have interfered with communications among communities of scholars, professionals, and policymakers around the globe investing in the enactment of ITE.

Brief Historical Overview of IE

Several key developments have advanced the idea of IE to address the educational rights and needs of SWD and other forms of difference. One example is the 1990 World Conference on Education For All (EFA) (Haddad, Colletta, Fisher, Lakin, & Rinaldi, 1990 ). This conference was held in Jomtien, Thailand, for the launching of the EFA movement, and was guided by the objective to “reaffir the long-standing idea of education as a human right . . . and urged all countries to provide for the basic learning needs of all people” (Florian, 2014 , p. 48). The EFA movement has contributed in multiple ways to the establishment of international accountability efforts to measure and track the impact of education for all students. Over time, as the IE movement has gained traction at a global level, the EFA movement has become more closely associated with a human rights issue.

One outgrowth of the connection and expansion of IE and EFA is the concept of inclusion as increasingly applied to other groups of students, especially those historically marginalized from access to education. Developing this argument further, Florian ( 2014 ) explained that the definition of IE

was broadened beyond the education of students with disabilities to encompass Roma children, street children, child workers, child soldiers, and children from indigenous and nomadic groups-in other words, anyone who might be excluded from or hav[e] limited access to the general education system within a country. (p. 48)

Other national and multinational policies have also moved to recognize the validity of concerns for the fundamental human rights of all children to access education. This growing international focus and prioritization on IE as an indispensable human right coalesced in an international event hosted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) event in 1994 in Salamanca, Spain. Participation in this historical event included representatives from 92 governments and 25 international organizations. The 1994 World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality Conference also produced a lasting effect on IE policies through the creation and ratification of the UNESCO/Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education ( 1994 ).

One critique often made about the IE literature is that despite its original aspirations, the bulk of the IE scholarly base in the developed world has emphasized disabilities at the expense of attention to other forms of difference (e.g., social class, gender, language). In the United States, for instance, IE has been highly dependent on federal government policies, which stipulate how to meet the needs of SWD. The precursors of IE in the United States were primarily grounded in the passage of essential laws in the 1970s, such as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHC) in 1975 (Labaree, 1988 ; Trent, 1994 ; Turnbull & Turnbull, 2000 ), which mandated the enrollment of SWD in public schools. O’Connor and Ferri ( 2007 ) described such special education policy in the United States as “fundamentally chang[ing] the foundation of special education” (p. 64), which challenged how teacher education programs taught IE to pre-service teachers.

Within the United States, special education policies guaranteed that SWD have the right to a Free and Appropriate Education in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) possible (Brantlinger, 2006 ). In the United States, LRE requirements have existed since the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHCA) in 1975 and constitute a fundamental element of the nation’s policy for educating SWD. The EHCA was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in 1990 , followed by its reauthorization in 2004 (Brantlinger, 2006 ).

According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (20 U.S.C. § 1400 [2004]), the US Department of Education and the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) legal code do not use the terms inclusion or IE. Under section 612(a)(5) of the IDEA, to the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, must be educated with children who are not disabled.

As evident in US national legislation language, the absence of inclusivity terms suggests the definition rests on understandings that students learn together. Further, special classes, separate schooling, or other removals of children with disabilities from the regular education environment occurs only where teachers cannot satisfactorily educate a child in regular classes due to the nature or severity of the disability, even with the use of the supplementary aids and services.

Within the United States’ discourse, LRE has thus been taken by advocates, state, and district organizations to mean inclusion into mainstream education, wherein SWD are physically located and educated in the same room as their nondisabled peers. The concept of mainstreaming, according to Lipsky and Gartner ( 1997 ), emphasized the place in which special education took place, and it assumed “the existence of two separate systems—general and special education—and was applicable to those students who were considered to be ‘normal’” (p. 77). Lipsky and Gartner contextualized the ongoing debate around IE in the United States as follows: “The issue in the United States . . . where students with disabilities should be educated has been inextricably intertwined with the issues of whether and how they should be educated” (Lipsky & Gartner, 1997 , p. 73). Thus, for practitioners and scholars who subscribe to the medical model of disability, definitions of IE may rely more on students’ disabilities and less on other intersecting demographic characteristics (i.e., second language status). Hence, to educate an SWD within the physical realms of a mainstream general education classroom is to comply with US education policy mandates.

IE Policies and Definitions Beyond the United States

Within Europe, the New Labour party influenced government efforts for inclusion, placing IE at the “centre of its educational agenda,” shifting responsibility for meeting student needs to teachers in the “ordinary classroom” (Armstrong, 2005 , p. 140). Just as US federal laws and education policy assumed a supervisory role over the integration of SWD and special education programs into general education classrooms in the latter half of the 20th century , so too did the central government in the United Kingdom in the 1970s and 1980s (Hodkinson, 2009 ; Trent, 1994 ). Terzi ( 2005 ) described this era of education policy as “watershed in the educational provision for disabled learners in the United Kingdom, whilst at the same time establishing a new fundamental framework for special education” (p. 443). Changes to education policy in the United Kingdom in this era were informed by the recommendations of the Warnock Committee, which published the Warnock Report in 1978 (Terzi, 2005 ; West, 2015 ).

The significance of the Warnock report comes from what it spurred in terms of IE policy reforms. In all, the Warnock report included an assembled list of over 200 recommendations for education policy reforms that affirmed the education goals for all children, including SWD. Central to the policy recommendations of the Warnock report were changes in the expectations for multiple stakeholder groups in education. Parents of SWD and handicaps formally attained an affirmation of the right of their children (SWD) to be enrolled and educated in mainstream classrooms (Buss, 1985 ). A second critical change in stakeholder expectations involved the expectations and responsibilities of mainstream classroom teachers to ensure the learning of all students in their classrooms, which now included SWD (Buss, 1985 ). With changes in the responsibility of teachers in mainstream classrooms, to teach classes integrated with students of all ability levels, the committee recognized the need to focus and strengthen teacher education programs to prepare teachers for such a change. Buss reported ( 1985 ) teacher preparation was named as one of three areas of top “priority” in the Warnock committee’s report (Buss, 1985 , p. 123).

Due to the committee’s policy recommendations, structural changes in administration and monitoring of local school boards took place. One repercussion of the implementation of the committee’s recommendations was a bureaucratic shift in supervision and management between local and centralized control and oversight of policy implementation and students’ educational outcomes. The shift from local to centralized control was predominantly located in the changes felt by local school boards. Whereas school boards previously functioned with autonomy, and mostly controlled local district issues, the Warnock reforms decreased local school board power and simultaneously consolidated control in the centralized UK ministry office (Buss, 1985 ; Slee, 2001 ; Terzi, 2005 ; West, 2015 ). In addition to the shift from localized to centralized control, central education ministries sought to maintain influence over local school boards by funding stipulations and compliance measures (West, 2015 ) much like the US case. The Warnock report also influenced the educational policy discourse related to disability and inclusion.

Within the committee’s suggestions to “integrate” (Buss, 1985 , p. 122) mainstream classrooms, the committee introduced a shift in the language used to describe special education students. The committee recommended dismissal of the term handicapped and recommended the use of the phrase “students identified with special education needs (SEN)” (Buss, 1985 , p. 123). The terminology change broadened the population of students considered part of the subgroup (Terzi, 2005 ). The term students with a disability was viewed in the United Kingdom as problematic because it suggested a permanence to disability or handicap that did not fit the educational experiences of all students. According to the Warnock committee, such a conceptualization implied that only a small subset of the population would need specialized help (West, 2015 ). Whereas the previous term handicapped could be understood to apply to a learner classified with an identifiable, documented disorder or permanent disability , the new term SEN could apply to any learner who might encounter the need for specialized learning needs at any period during their educational tenure (Slee, 2001 ; Terzi, 2005 ; West, 2015 ). Restructuring this distinction from handicapped , language used to refer to SWD or specialized learning needs became “central to the debate in special and inclusive education, where it is also referred to as the dilemma of difference” (Terzi, 2005 , p. 443). The “dilemma of difference” represents the challenges of IE to acknowledge and support student’s individualized learning needs (Terzi, 2005 , p. 443). The use of difference, in turn, is the process of highlighting dissimilarities while also “accentuating the sameness” (Terzi, 2005 , p. 443), to create and promote commonalities while supporting children’s needs.

A crucial third provision from the policy reforms in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom addressed the types of training and experiences that teacher preparation programs included. In England, IE’s current character has also been traced back to the 1960s, when issues of segregation became highly debated (Hodkinson, 2009 ). Although IE became a truly global movement, at least in terms of nations embracing its basic tenets, the enactment of this laudable idea has been fraught with controversies and tensions, which have, in turn, spilled over into efforts to create and implement ITE programs.

Consequences of IE’s Ambiguities and Tensions for ITE

All in all, scholars agree there is a “substantial distance between the conceptualization of inclusive education and its implementation” (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 , p. 5). Echoing Srivastava, de Boer, and Pijl ( 2015 ), Artiles and Kozleski illustrated, “given the multi-voiced nature of the inclusion movement, it is not surprising that its bold aspirations traveled across locales and time with disparate meanings and with alternative consequences” (p. 5). Not surprisingly, the lack of conceptual clarity and ambiguity about IE’s definition has had consequences for the implementation of ITE. For instance, tensions between those proponents and those who opposed IE have contributed to a lack of clarity within the primary goals of ITE (Brantlinger, 1997 ). For example, given the dominant discourse on disability-based inclusion, there is limited research on what IE means for students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. To wit: “Under the guise of establishing an ‘inclusive’ educational system promoted by national edicts, local interpretation and implementation have in many instances been far from the original intention” (Forlin, 2012 , p. 4). To summarize, ITE in “most regions has been tokenistic at best and non-existent at worst” (Forlin, 2012 , p. 4). As such, due to policy and changing economic demands, teacher educators face challenges to create inclusive programs and models (Sindelar, Wasburn-Moses, Thomas, & Leko, 2014 ). To address this state of affairs, Florian ( 2014 ) offered four strategies that facilitate the implementation of ITE:

[Greater] clarity about what inclusion means in different contexts and the implications for teacher education.

[Advance] high-quality programs of research designed to help answer questions about what teachers need to know and be able to do to implement a policy of inclusive education,

Move away from binary distinctions between special and inclusive education, [and]

[Pursue] new forms of professional collaboration.

(Florian, 2014 , pp. 214–219)

As such, some of the trends and discourses echo Florian’s (and other researchers’) call to advance the implementation of ITE. Next, we outline ITE conceptualizations in the next sections and summarize trends in the ITE research literature.

ITE: Trends and Discourses

In the first section, we delineate our search criteria and explain our categorization of the literature. Next, we present our findings related to two core areas: (1) general conceptualizations of ITE and (2) ITE program components and structure.

General Conceptualizations of ITE

We discuss conceptualizations of ITE by synthesizing the results of 14 empirical studies and seven literature reviews published between 2005 and 2017 . We located publications by conducting keyword searches in our institution’s library system using variations of the terms inclusive education or inclusive teacher education , narrowed by publication type (e.g., empirical or literature review) and publication date. Specifically, we targeted studies that included the preparation of teachers for teaching students with SEN. We eliminated conceptual pieces, as well as articles focused on professional development for in-service teachers. We included publications related to ITE when the study included both pre- and in-service teachers. We included literature reviews published in peer-reviewed journals or book chapters published in diverse geographical regions. Some authors explicitly noted a country or geographic area or focus, while others did not specify the limits of the review. One author (Hodkinson, 2009 ), stated the literature review was specific to England, while the other three (Hoffman et al., 2015 ; Kurniawati, De Boer, Minnaert, & Mangunsong, 2014 ; Orakci, Aktan, Toraman, & Çevik, 2016 ) did not specify if researchers restricted particular studies to specific geographic location. For literature reviews where researchers did not specify the location, we assumed studies were not limited by geographical area since authors pulled from databases that extend beyond national borders (i.e., EBSCO, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, ERIC, MEDLINE, Psycho ARTICLES, Psycho INFO; Soc Index).

We categorized literature reviews and empirical studies into two groups: basic and comprehensive conceptualizations of ITE. Here, we used the term basic conceptualization to refer to texts that defined inclusion limited to pre-service teachers’ training primarily focused on students’ SEN. In contrast to basic conceptualizations of ITE, we used the term comprehensive to specify research that recognized students’ multiple learning needs, work emphasizing teachers’ sociocultural knowledge and critical reflexivity (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ).

Specifically, publications we categorized as basic did the following: (a) focused on disability only and (b) were based on the assumption that disability is permanent; there was little discussion on how students’ learning needs can change over time. These publications focused on students’ abilities and disabilities and were primarily grounded in the medical model of IE. For instance, studies categorized as basic conceptualizations of ITE emphasized proper interventions to support student learning, presumably due to the existence of a disability. Further, in such publications, researchers emphasized school personnel perceptions of students, stemming from the notion that a disability exists within the body or mind that merits specialized assistance. In these publications, we observed there was little or no discussion about how institutions might address diversity beyond the students’ disability or multiple identity markers (i.e., race, ethnicity, language, gender). Based on authors’ reports, the literature categorized as basic did not recognize that students with SEN may also live in poverty, speak multiple languages, have different gender orientations, or identify from a particular minoritized ethnic group.

Literature reviews and empirical studies based on comprehensive views of ITE focused on factors beyond students’ SEN, not limited to perceptions or attitudes centered on students’ disabilities. Comprehensive conceptualizations of ITE included “sharpening inclusion’s identity, attending to the fluid nature of ability differences and students’ multiple identities, broadening the unit of analysis to systems of activities, and documenting processes and outcomes” (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 , p. 2). We categorized these publications as comprehensive ITE if the authors did one of the following: (a) recognized that SWD have multiple social identity markers (i.e., gender, race, disability) and (b) discussed topics such as diversity, race, ethnicity, or language background in a substantive manner. Likewise, we found authors’ argumentation about ITE was especially attuned to recognizing the social and systemic power structures that contribute to educational disparities. In sum, we defined this trend as recognizing the multiplicity of students’ social identity markers beyond ability, not restricted to a view of disabilities as residing solely in the body or mind, which then requires a fix or cure to their ailments (Artiles, 2013 ; Trent; 1994 ).

Comprehensive conceptualizations of ITE also included studies in which scholars connected the work of ITE to include pre-service teachers’ learning and training to become agents of change for social justice. Pantić and Florian ( 2015 ) summarized this type of work as follows:

Preparing teachers to act as agents of change for inclusion and social justice challenges some of the well-established ways of thinking about teaching as an individualistic teacher-classroom activity. Teacher competence as agents of inclusion and social justice involves working collaboratively with other agents, and thinking systematically about the ways of transforming practices, schools, and systems. (p. 346)

In other words, this view of ITE accounts for the historical and social processes of systems (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016 ). Similar to multicultural education, Banks and Banks ( 2010 ) conceptualized inclusion as the “idea that all students—regardless of their gender, social class, and ethnic, racial or cultural characteristics—should have an equal opportunity to learn in school” (p. 1). Salend ( 2010 ) echoed earlier work ( 2008 ), expanding upon the notion of reconceptualizing inclusion, and noted,

thus, in many countries social justice and multicultural education are viewed as being inextricably linked to inclusive education, which has broadened the focus of inclusive education beyond disability to include issues of race, linguistic ability, economic status, gender, learning style, ethnicity, cultural and religious background, family structure, and sexual orientation. (p. 131)

Basic Conceptualizations

Publications classified as basic conceptualizations focused on the exploration of pre-service teachers’ attitudes and beliefs, mainly focused on disability as a single identity marker. We classified texts as basic conceptualizations if authors’ discussions of diversity as related to IE were limited in both substance and content. To illustrate, Orakci, Aktan, Toraman, and Çevik ( 2016 ) differentiated study participants by gender and examined teacher attitudes toward IE. Of 51 studies reviewed, Orakci and colleagues found gender and special education training did not affect teacher attitudes toward IE, but they found the focus of teacher training (i.e., preschool, special education) made a significant difference. Orakci and colleagues ( 2016 ) also included a minimal number of pre-service teachers (n = 7) and a much larger number of in-service teachers (n = 44). We emphasized Orakci and colleagues’ work since their work illustrates the need to focus on training, rather than seeking to attribute teacher preparation to teachers’ sociocultural characteristics (e.g., gender). In another review examining pre-service teacher beliefs and attitudes about IE, Hoffman and colleagues ( 2015 ) found pre-service teachers had limited opportunities to engage in critical discussions with their mentor teachers. The authors found that mentor teachers dominated speaking time, were more focused on technical aspects of teaching, rather than dispositions, and minimally engaged in thoughtful discussions (Hoffman, 2015 ) related to students’ intersectional differences (e.g., language and SEN).

In addition to the research included in these reviews on teacher candidates’ beliefs and attitudes, we identified other studies in this category that delved into discussions about IE and methodological considerations in this area of inquiry. Robinson’s ( 2017 ) action-research project conducted in the context of a university-school partnership intended to “promote positive discourse of diversity (celebration of the richness of human variety)” (p. 21). Including instructional assistants, experienced teachers, and student teachers, Robinson sought to determine which practices and beliefs could produce effective inclusive practices. Robinson explained, “the concept ‘inclusion’ would trigger diversity discourses (which celebrate diversity and uniqueness), but ‘SEN’ would trigger disparity discourses (where diversity is associated with pathologisation, differential treatment and different expectations)” (p. 31). Robinson’s study included four significant findings: (a) school personnel varied in their feeling of adequacy and disposition to teach [SEN] students (i.e., some feeling more positive, versus feeling amateur or panic); (b) contrasting discourses, which included school personnel operating alongside deficit discourses; (c) development of collaborative skills and a deeper understanding of the “value of teamwork” (p. 38); and (d) the value of including other school personnel, such as instructional assistants for the work of IE. We noted that, while topics of diversity were a crucial part of the study, discussions centered on attitudes and perceptions toward students’ disabilities and abilities, or they included limited discussions about what was meant by diversity.

In a study focused on preparing physical education teachers toward inclusion, Taliaferro, Hammond, and Wyant ( 2015 ) examined pre-service physical education teachers’ self-efficacy toward the integration of SWD in the general education classroom. Similarly, Taliaferro and colleagues mentioned the word diversity, but there was little discussion about what was meant by diversity. Likewise, Tangen and Bentel ( 2017 ) examined the perceptions of 46 pre-service educators enrolled in a graduate entry teacher education program in Australia. Tangen and Bentel investigated pre-service teachers’ theoretical understandings and perceptions of themselves toward IE. Tangen and Bentel found pre-service teachers failed to have a “sophisticated insight into the nuances in differentiating between the terms of diversity and inclusion” (p. 67) since pre-service teachers conceptualized inclusive practices in varying ways. For instance, some pre-service teachers found IE as not entirely possible, since often many other factors (ill-prepared teachers, large classroom sizes) contributed to student outcomes. Tangen and Bentel briefly commented, “during the semester . . . [pre-service teachers] recounted how they or students were marginalized if they were ‘different,’ such as if a student had a visible disability or had limited English proficiency” (p. 70), yet teachers failed to provide sophisticated understandings of what was meant by diversity. Again, since Tangen and Bentel maintained the focus on diversity (not explaining why this mattered), we categorized the study as basic. In sum, studies categorized as basic largely failed to acknowledge more “fluid and nuanced” (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 , p. 446) notions of diversity (beyond one identity marker) or the social power structures that contribute to disparities within ITE. Next, we turn to studies categorized as encompassing more holistic conceptualizations of ITE.

Comprehensive Conceptualizations of ITE

We categorized publications as comprehensive conceptualizations if authors defined students’ learning needs as not exclusive to disability. This approach recognizes students’ multiple needs, such as the intersections of language and disability. We highlight a few publications that illustrated the various ways that researchers conceptualized ITE beyond disability.

Our first example covered studies published between 1990 and 2003 , based on Brownell and colleagues’ analysis of 64 publications and their discussion of the concept of diversity beyond students’ ability differences (Brownell, Ross, Colón, & McCallum, 2005 , p. 245). Of interest was how Brownell and colleagues’ review defined diversity as related to cultural factors, beyond a student’s disability status. Brownell and the research team found that in 84% of the programs they analyzed, cultural diversity was mentioned as a topic, although the authors of those studies did not always elaborate on pedagogical training that could help pre-service teachers learn essential skills for ITE. Brownell and colleagues also found that in 28% of the articles reviewed, authors described methods intended to address cultural or linguistic needs of students. Brownell and associates also found that in 50% of the programs, authors addressed both inclusion and cultural diversity, “reflecting a broader focus on diversity that included children with disabilities as well as those with diverse cultural and linguistic needs” (p. 246). Brownell and colleagues’ review stands out because they specified what was meant by diversity, such as social or linguistic needs.

Similarly, Harry and Lipsky ( 2014 ) reviewed the empirical base to examine the relationship between research methods used and the types of inquiry projects on ITE. Harry and Lipsky identified 41 reports, of which 25 used qualitative or mixed methods, and 14 relied on quantitative methods. Interested in investigating the shift toward embracing constructivist approaches within ITE, Harry and Lipsky identified four categories, which illustrated understandings of ITE as “inclusion and collaboration; field experience; specialized competencies program philosophy; and conceptual change (where conceptual change is sometimes related to program philosophy and at other times related to multicultural diversity)” (p. 450). Harry and Lipsky identified two studies that focused on conceptual change regarding philosophical approaches in ITE programs, specifically, whether participants had positivist or constructivist orientations. Since Harry and Lipsky emphasized the need for conceptual change in the field of ITE, we identified their work aligned with comprehensive orientations. Harry and Lipsky found an overall pattern, “whereby the more constructivist the question, the greater the reliance on qualitative methods,” which were “more consistently used in studies on social process” (p. 458). Harry and Lipsky clarified these findings did not necessarily suggest the need for more qualitative methods, but, instead, future research should explore the use of direct observational methods (e.g., video, audio recording), rather than continuing to use more limited, self-reported data. We concluded this work highlights essential methodological and theoretical implications for ITE.

Pugach, Blanton, and Boveda ( 2014 ) reviewed research on teacher preparation intended to “foster inclusive educational practice” (p. 144) and focused on collaborative efforts across general and special education. Pugach and colleagues reviewed research published between 1997 to 2012 and included 30 studies examining pre-service teacher education program components and design, which focused on collaborative approaches. They discussed students’ intersectional needs (e.g., special education and second language needs), in addition to examining pre-service teacher identity development, program redesign, and evaluation. Pugach and colleagues noted overall trends:

program evaluations have not focused on student identity development as a result of program completion, or the relationships between various parts of the curriculum such as those between teaching English Language Learners and teaching students who have disabilities, or the specific ways that strands of content about disability have been integrated into the content. (p. 154)

Thus, these discussions pointed to authors’ recognition of students’ intersectional needs, something apparently limited in the research base. Further, Pugach and colleagues noted hopeful results related to observing teacher educators working in collaborative ways between general and special education teachers. They did warn, however: “In light of the willingness to engage in such joint inquiry . . . more complex designs could be developed and more complex issues problematized around this important pre-service program trend” (Pugach et al., 2014 , p. 154). Further, the authors also remarked on a “gap in the way researchers addressed social identity markers in addition to disability” (Pugach et al., 2014 , p. 154). Additionally, Pugach and colleagues’ observation noted researchers’ tendency to reference participant demographics inconsistently within studies included in their review. By highlighting collaboration and training in ITE, the authors stressed the importance of recognizing learning as a shared experience. Not only did researchers discuss the importance of students’ identity markers beyond SEN, but additionally, they expanded on how systems might address students’ needs beyond special education factors.

To summarize, it is vital that ITE programs recognize and prepare teacher candidates to understand that teaching must be designed to address students’ multiple needs, beyond their SEN. As such, broader conceptualizations of ITE can be very potent for the support of students who have SEN, due to a specific learning disability and who are identified as second language learners or have other learning needs.

ITE Program Components

ITE program structure includes different components, such as curriculum, coursework, field-based learning experiences, and dispositions (Salend, 2010 ; Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ; Pugach et al., 2014 ). Salend ( 2010 ) argued that ITE program components include “core beliefs” (p. 130), and constitute additional essential elements; these beliefs may influence pedagogical practices, learning activities, and quality of ITE. These program components are informed by how ITE program staff and administrators define the purpose of inclusion (Salend, 2010 ).

Beyond coursework and curriculum, field-based learning experiences are also significant for the formative development of inclusive pre-service teachers (Salend, 2008 , 2010 ). An essential component of ITE programs is field placement since it affords opportunities for exposure to the complex realities of student learning and classrooms. Field-based internships typically include teacher candidate assignment in the field with the goals of offering interactive teaching experiences and mentorship by veteran teachers. For instance, researchers have shown that debriefing, reflective sessions by department faculty and in-service teachers, is essential in shaping the mindsets and attitudes of pre-service teachers toward inclusion (Arthur-Kelly, Sutherland, Lyons, Macfarlane, & Foreman, 2013 ).

We categorized studies and reviews into two core areas, identified as limited and dynamic program structure. We identified limited program considerations of IE when publications met one of two criteria: (1) a focus on one aspect of program structure or (2) a basic conceptualization of ITE (e.g., focused on disability). Moreover, we found that while researchers commonly referenced the technical parts of ITE program structure, not all IE scholars used the term “competencies” (Salend, 2008 ; 2010 , p. 131) in the same way, or viewed a programmatic emphasis on competencies as uniformly beneficial. For example, Salend ( 2010 ) presented an argument that “core beliefs” (Salend, 2008 ; 2010 ) are grounding points that impact “curriculum, courses, and competencies” as well as “pedagogical practices [and] learning activities” (p. 131). In contrast, Harry and Lipsky ( 2014 ) posited that when ITE programs focused on mastery of competencies, there was less emphasis on constructivist learning and critical development of reflective dispositions amongst pre-service teachers.

On the other hand, we classified texts as dynamic ITE work (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ) when authors reported core beliefs interwoven across coursework and field-based experiences. Dynamic ITE programs explored and supported pre-service teacher learning and dispositions toward comprehensive views of inclusion that included disability, encompassing social and cultural knowledge (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ). Further, we considered dynamic ITE programs provide opportunities for teacher candidates to observe teachers and practice pedagogical skills within their field-based experiences in inclusive classrooms (Salend, 2010 ). Salend ( 2010 ) stated these types of experiences are critical, as they are intended to help link theory to practice. These practices also offer opportunities for teachers to “think critically about their values and beliefs and practices” (Salend, 2010 , p. 132). In sum, dynamic ITE programs support pre-service teacher development of skills beyond students’ SEN, to include multiple factors, emphasizing students’ sociocultural and learning needs.

Examples of Limited ITE Programmatic Components . In this section, we highlight a few examples of ITE literature we categorized as limited program components. For example, Hodkinson found there was little evidence that classroom practices have changed significantly since the 1970s, particularly regarding the preparation of special education teachers. Hodkinson called upon Winter’s ( 2006 ) work, which explained the lack of training on SEN and inclusion as limited preparation:

which indicate[s] that trainees can receive as little as 10 hours of training on SEN issues, it appears that mandatory and discrete training in SEN and inclusion is seemingly not favoured as an approach to the training of pre-service teachers within England. (p. 285)

Relatedly, Hoffman and colleagues’ ( 2015 ) studied the impact of coaching interactions between cooperating teachers (mentor teachers) and pre-service teachers in field-based experiences. In their review of 46 empirical studies, Hoffman and colleagues found ITE programs heavily relied upon mentor teachers’ feedback for the development of teacher candidates’ dispositions. However, problems arose when authors reported few mentor teachers had professional training on how to formally mentor pre-service teachers. As a result, Hoffman and colleagues found few mentoring teachers engaged in practices that included critical reflexivity, an essential aspect for teaching responsive to students’ multiple sociocultural needs.

Similarly, Kurniawati, De Boer, Minneart, and Mangunsong ( 2014 ), examined multiple program components, but only focused on disability-related needs. In their review, the authors located 13 studies used to analyze program structure and content. In their analysis, Kurniawati and colleagues found, the majority of training programs focused on “attitudes, knowledge, and skills” (p. 130) limited to SWD. Similarly, we noted these publications illustrated limited discussions of the multiple components needed to train pre-service teachers in ITE programs and the dispositions needed in preparing teachers to work in inclusive classrooms.

We categorized a small number of studies as limited ITE programming if researchers’ projects focused on attitudes or beliefs about disability (Campbell, Gilmore, & Cuskelly, 2003 ; Orakci et al., 2016 ; Taliaferro et al., 2015 ; Tangen & Bentel, 2017 ). In this small number of studies, researchers focused on one key aspect of programmatic structures (e.g., dispositions), but did not connect the work to other essential program components. Since discussions to other program components were somewhat limited, we did not expand on study reports. Mainly, because researchers did not relate findings across program structures, we found it difficult to argue their results have implications for ITE program components. We clarify, the purpose of the classification scheme is not to disparage ITE scholarship, but to illustrate the different approaches in how researchers have conceptualized factors that matter within ITE program components.

Examples of Dynamic ITE Programmatic Components . We identified the literature as dynamic when ITE scholars drew upon comprehensive definitions of IE, and researchers examined connections across program components. For example, dynamic conceptualizations challenged teacher candidates previous assumptions about inclusion through ongoing, mediated discussions about pedagogical stances or professional dispositions. In their review of ITE programs, Harry and Lipsky ( 2014 ) noted some department programming was unique in its focus on multicultural education and bilingual special education. In turn, dynamic program components offered the opportunity to end the siloed training of general and special education teachers (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ).

In literature categorized as dynamic program structure, authors reported preparation curricula designed to support teacher candidate learning related to students’ social, cultural, and SEN (Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ). For example, Brownell and colleagues ( 2005 ) reviewed 64 ITE program descriptions and evaluations between 1990 and 2003 . Brownell and colleagues found in 22 (34%) program descriptions, authors mentioned “cultural diversity as program topics” (p. 246). Brownell and colleagues highlighted the importance of “collaboration, between faculty, school personnel, and pre-service and in-service teachers” (p. 246). They emphasized the need for “early, extensive, and collaborative field experiences” (Brownell et al., 2005 , p. 245), which could help shape pre-service teachers’ learning about inclusive practices. Brownell and colleagues ( 2005 ) also concluded four essential characteristics of programs that could impact teacher’s understandings of inclusive practices and teaching, which included:

(a) the use of pedagogy that helps pre-service teachers to examine their beliefs, (b) a strong programmatic vision that fosters program cohesion, (c) a small program size with a high degree of faculty-student collaboration, and (d) carefully constructed field experiences in which university and school faculty collaborate extensively. (p. 245)

Researchers also reported studies that we categorized as evidence of dynamic program structure through field experiences in Australia (Carrington, Mercer, Iyer, & Selva, 2015 ). Using a social and critical theoretical framework, Carrington and colleagues investigated a “critical service learning” approach, with the goals of instilling values “suitable to inclusive practices and appreciation of diversity in schools” (p. 2). Carrington and colleagues suggested that field placements were critical in shaping pre-service teacher values, attitudes toward disability, inclusive education, and acceptance of SWD in their classes, with a focus on “social justice-oriented model[s]” (p. 4). Such opportunities were useful in preparing teacher candidates to see the complexities of the social, cultural, and political contexts of learners with SEN, similarly noted by Robinson ( 2017 ). Additionally, according to Harry and Lipsky’s ( 2014) review, O’Brian, Stoner, Appel, and House ( 2007 ) examined the relationships between mentor teachers and pre-service teachers. O’Brian and colleagues found “pre-service teachers relied greatly on the development of a trusting relationship with their cooperating teachers, and that relationships were dynamic, developing in gradual process in which the roles of both parties were negotiated and became clearer” (as cited in Harry & Lipsky, 2014 , p. 455). In another example of dynamic ITE programs, Hanline ( 2010 ) utilized weekly reflective journals and semester evaluations in pre-service early childhood special education teachers (as cited in Harry & Lipsky, 2014 ). According to Harry and Lipsky, in Hanline’s study, pre-service and mentor teachers kept journal entries that included observational notes and self-reflection, producing 182 journal entries and 45 supervision observations and “end-of-semester practices as codes” (p. 455). Based on analyses of this data, we noted intervention strategies within field experiences, which provided pre-service teachers opportunities to become comfortable teaching in inclusive classrooms. We interpreted these programmatic components as optimal for reflecting on students’ multiple needs, critical for IE.

Grounded in the notion of inclusivity and collaboration, Pugach and colleagues ( 2014 ) also explored the empirical base with the goals of advancing inclusion. Their goal was to explore how teacher education research might bring special and general education closer together. In their study, Pugach and colleagues extended the idea that field-based experiences matter. For example, they found “adding content, an activity, or an experience to the curriculum” (p. 148) enriched teacher candidates’ field-based experiences. At the same time, while Pugach and colleagues found both pre-service and mentor teachers shared the value of collaboration, without “intentionality,” these experiences may have resulted in “diminished opportunities for student teachers to create a sense of independence and autonomy” (p. 148).

Drawing from Barbara Keogh and colleagues’ previous work (e.g., Keogh, Major, Reid, Gandara, & Omori, 1978 ), Pugach and colleagues ( 2014 ) illustrated the need for ITE to use “marker variables” to “create some level of common understanding of and comparability in sample characteristics across studies to advance more meaningful research on the definition of learning disabilities” (p. 157). Pugach and colleagues explained the reasoning behind marker variables as,

Proposing such a set of marker variables at this point in time might serve… to begin to foster discussion about some of the gaps in how the research is conceptualized. Asking researchers to think about variables that have been relatively absent to date might foster intentionality. (p. 157)

Emphasizing the need for intentionality as a “lens for developing future research agenda” (p. 155), Pugach and colleagues’ concluded by emphasizing future research should continue to explore the relationship between intentionality and ITE.