- Help & Terms of Use

Academic integrity: a literature review

- School of Education

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article (Academic Journal) › peer-review

- academic integrity

- methodology

Access to Document

- 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

- Persistent link

Fingerprint

- Literature Reviews Social Sciences 100%

- Integrity Social Sciences 100%

- Research Social Sciences 50%

- Professional Personnel Social Sciences 25%

- Service Industries Social Sciences 25%

- Standards Social Sciences 25%

- Research Worker Social Sciences 25%

- Surveys Social Sciences 25%

T1 - Academic integrity: a literature review

AU - MacFarlane, Bruce

AU - Zhang, Jingjing

AU - Pun, Annie

N2 - This article provides a literature review on academic integrity, which encompasses the values, behaviour and conduct of academics in all aspects of their practice. This is a growing area of academic research as a result of the expansion of higher education on a global basis and concerns about standards of professional conduct. The article maps the main strands of research on academic integrity by reference to teaching, research and service using 115 articles derived from both western and Chinese literature. The review indicates that much of the literature is framed in terms of misconduct or academic corruption with research ethics the dominant focus. Researchers investigating academic integrity draw predominantly on multivariate analysis using surveys/questionnaires, documentary analysis and, more occasionally, interviews. While there has been rapid growth in the literature, a stronger focus is needed on identifying ?ethical? as well as ?unethical? practice despite the methodological challenges in overcoming social desirability reporting

AB - This article provides a literature review on academic integrity, which encompasses the values, behaviour and conduct of academics in all aspects of their practice. This is a growing area of academic research as a result of the expansion of higher education on a global basis and concerns about standards of professional conduct. The article maps the main strands of research on academic integrity by reference to teaching, research and service using 115 articles derived from both western and Chinese literature. The review indicates that much of the literature is framed in terms of misconduct or academic corruption with research ethics the dominant focus. Researchers investigating academic integrity draw predominantly on multivariate analysis using surveys/questionnaires, documentary analysis and, more occasionally, interviews. While there has been rapid growth in the literature, a stronger focus is needed on identifying ?ethical? as well as ?unethical? practice despite the methodological challenges in overcoming social desirability reporting

KW - academic integrity

KW - literature

KW - methodology

KW - ethics

U2 - 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

DO - 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

M3 - Article (Academic Journal)

SN - 0307-5079

JO - Studies in Higher Education

JF - Studies in Higher Education

- Skip to main content

This site belongs to UNESCO’s International Institute for Educational Planning

- Codes of conduct

- Share on Twitter (New window)

- Share on Facebook (New window)

- Send by email

Academic integrity: a review of the literature

Author(s) : Macfarlane, Bruce; Zhang, JingJing Zhang; Pun, Annie

Imprint : 2012

Collation : p. 339-358

Series : Studies in higher education, v. 39, no. 2

This article provides a literature review on academic integrity, which encompasses the values, behaviour and conduct of academics in all aspects of their practice. This is a growing area of academic research as a result of the expansion of higher education on a global basis and concerns about standards of professional conduct. The article maps the main strands of research on academic integrity by reference to teaching, research and service using 115 articles derived from both western and Chinese literature. The review indicates that much of the literature is framed in terms of misconduct or academic corruption with research ethics the dominant focus. Researchers investigating academic integrity draw predominantly on multivariate analysis using surveys/questionnaires, documentary analysis and, more occasionally, interviews. While there has been rapid growth in the literature, a stronger focus is needed on identifying ‘ethical’ as well as ‘unethical’ practice despite the methodological challenges in overcoming social desirability reporting.

- Academic fraud, Codes of conduct, Corruption, Diagnostic tools / surveys, Ethics, Globalization, Integrity, Research, University staff, Higher education

- International

- About the Repository

Academic integrity: A review of the literature

- Department of Education Policy and Leadership (EPL)

Research output : Contribution to journal › Articles › peer-review

- Academic integrity

- Methodology

Access to Document

- 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

Other files and links

- published version (EdUHK Users only)

Fingerprint

- integrity Social Sciences 100%

- literature Social Sciences 48%

- social desirability Social Sciences 33%

- research ethics Social Sciences 32%

- teaching research Social Sciences 30%

- multivariate analysis Social Sciences 29%

- corruption Social Sciences 26%

- questionnaire Social Sciences 14%

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, academic integrity in online assessment: a research review.

- Department of Psychology, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

This paper provides a review of current research on academic integrity in higher education, with a focus on its application to assessment practices in online courses. Understanding the types and causes of academic dishonesty can inform the suite of methods that might be used to most effectively promote academic integrity. Thus, the paper first addresses the question of why students engage in academically dishonest behaviours. Then, a review of current methods to reduce academically dishonest behaviours is presented. Acknowledging the increasing use of online courses within the postsecondary curriculum, it is our hope that this review will aid instructors and administrators in their decision-making process regarding online evaluations and encourage future study that will form the foundation of evidence-based practices.

Introduction

Academic integrity entails commitment to the fundamental values of honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage ( Fishman, 2014 ). From these values, ethical academic behavior is defined, creating a community dedicated to learning and the exchange of ideas. For a post-secondary institution, ensuring that students and staff are acting in an academically integrous manner reinforces an institution's reputation such that an academic transcript, degree, or certificate has a commonly understood meaning, and certain knowledge and skills can be inferred of its holder. In turn, individual students benefit from this reputation and from the inferences made based on their academic accomplishments. At a broader level, understanding the fundamental values of academic integrity that are held within a community—and behaving in accordance with them—instills a shared framework for professional work, making explicit the value of the mastery of knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Fair and effective methods for promoting academic integrity have long been considered within postsecondary education. Yet, there is a widespread belief that departures from integrity are on the rise (e.g. Hard et al., 2006 ). With the introduction of technology into the classroom and the popularity of online classes, new opportunities for “e-cheating” exist (e.g. Harmon and Lambrinos, 2008 ; King and Case, 2014 ). Demonstrating the importance of considering “e-cheating,” prior to 2020, reports suggest that 30% of students in degree-granting U.S. colleges and universities enrolled in at least one online course ( Allen and Seaman, 2017 ), and 44% of faculty respondents reported teaching at least one fully online course ( Jaschik and Lederman, 2018 ). In 2020 and as of this writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused widespread changes to higher education, resulting in many institutions adopting online learning formats. As the development of fully online courses is expected to continue to expand (e.g., Allen and Seaman, 2010 ; Johnson, 2019 ), faculty and administrators are faced with the challenge of developing methods to adequately assess student learning in an online environment while maintaining academic honesty.

There are many new ways to cheat, some that are unique to the online course environment and some that are also observed within in-person courses; these include but are not limited to: downloading papers from the internet and claiming them as one’s own work, using materials without permission during an online exam, communicating with other students through the internet to obtain answers, or having another person complete an online exam or assignment rather than the student who is submitting the work ( Jung and Yeom, 2009 ; Moten et al., 2013 ; Rogers, 2006 ; Underwood and Szabo, 2003 ). In particular, both faculty and students perceive online testing to offer more cheating opportunities than in traditional, live-proctored classroom environments ( Kennedy et al., 2000 ; Rogers, 2006 ; Stuber-McEwen et al., 2005 , Smith, 2005 ; Mecum, 2006 ), with the main concerns being student collaboration and use of forbidden resources during the exam ( Christe, 2003 ).

The goal of this paper is to review and synthesize current research on academic integrity in higher education, considering its specific application to assessment practices in online education. Understanding the varied and complex types and causes of academic dishonesty can inform the suite of methods that might be used to most effectively promote academic integrity. Thus, we will address the question of why students engage in academically dishonest behaviours ( Why do Students Engage in Academic Dishonesty? ), and we will review methods to reduce academically dishonest behaviours (Section 3). We will do this with intentional consideration of four factors: individual factors, institutional factors, medium-related factors, and assessment-specific factors. Given the increasing use of online courses within the postsecondary curriculum, it is our hope that this review will aid instructors and administrators in their decision-making process regarding online evaluations and encourage future study that will form the foundation of evidence-based practices 1 .

Why do Students Engage in Academic Dishonesty?

Academic dishonesty (or “cheating”) 2 includes behaviors such as the use of unauthorized materials, facilitation (helping others to engage in cheating), falsification (misrepresentation of self), and plagiarism (claiming another’s work as one’s own; e.g., Akbulut et al., 2008 ; Şendağ et al., 2012 ), providing an unearned advantage over other students ( Hylton et al., 2016 ). Broadly, these behaviors are not consistent with an established University’s Standards of Conduct ( Hylton et al., 2016 ), which communicates expected standards of behavior ( Kitahara and Westfall, 2007 ). “E-dishonesty” has been used to refer to behaviors that depart from academic integrity in the online environment, and e-dishonesty raises new considerations that may not have been previously considered by instructors and administrators. For example, concerns in relation to online exams typically include ‘electronic warfare’ (tampering with the laptop or test management system), impersonation, test item leakage, and the use of unauthorized resources such as searching the internet, communicating with others over a messaging system, purchasing answers from others, accessing local/external storage on their computer, or accessing a book or notes directly (e.g. Frankl et al., 2012 ; Moten et al., 2013 ; Wahid et al., 2015 ). All of these types of behaviours are also considered under the broader umbrella term of ‘academic dishonesty’ ( Akbulut et al., 2008 ; Namlu and Odabasi, 2007 ), and we highlight them here to broaden the scope of considerations with respect to academic integrity.

There are many reasons why individuals may choose to depart from academic integrity. Here, we synthesize existing research with consideration of individual factors, institutional factors, medium-related factors, and assessment-specific factors. Much of the research to date considers the on-campus, in-person instructional context, and we note the applicability of much of this literature to online education. Where appropriate, we also note where research is lacking, with the aim of encouraging further study.

Individual Factors

Research based on what is referred to as the “fraud triangle” proposes that in order for cheating to occur, three conditions must be present: 1) opportunity, 2) incentive, pressure, or need, and 3) rationalization or attitude (e.g. Becker et al.2006 ; Ramos, 2003 ). These three conditions are all positive predictive factors of student cheating behavior ( Becker et al., 2006 ). Opportunity occurs when students perceive that there is the ability to cheat without being caught; this perception can occur, for example, if instructors and administrators are thought to be overlooking obvious cheating or if students see others cheat or are given answers from other students ( Ramos, 2003 ). The second condition, incentive, pressure, or need , can come from a variety of different sources such as the self, parents, peers, employers, and universities. The pressure felt by students to get good grades and the desire to be viewed as successful can create the incentive to cheat. Lastly, the rationalization of cheating behavior can occur when students view cheating as consistent with their personal ethics and believe that their behavior is within the bounds of acceptable conduct ( Becker et al., 2006 ; Ramos, 2003 ). Similar to the “cheating culture” account (detailed more fully in Institutional Factors ), rationalization can occur if students believe that other students are cheating, perceive unfair competition, or perceive an acceptance of, or indifference to, these behaviors by instructors ( Varble, 2014 ).

Though accounts based on the fraud triangle are well supported, other researchers have taken a more fine-grained approach, further considering the second condition related to incentive, pressure, or need . Akbulut et al. (2008) , for example, propose that psychological factors are the most significant factors leading students to e-dishonesty. Feeling incompetent and/or not appreciating the quality of personal works or one’s level of mastery ( Jordan, 2001 ; Warnken, 2004 ; Whitaker, 1993 ), a sense of time pressure ( DeVoss and Rosati, 2002 ; Sterngold, 2004 ), a busy social life ( Crown and Spiller, 1998 ), personal attitudes toward cheating ( Diekhoff et al., 1996 ; Jordan, 2001 ), and the desire to get higher grades ( Antion and Michael, 1983 ; Crown and Spiller, 1998 ) can cause an increase in academic dishonesty, including e-dishonesty.

In particular relation to online courses, some authors contend that the online medium may serve as a deterrent for academic dishonesty because it often supports a flexible schedule and does not lend itself to panic cheating ( Grijalva et al., 2006 ; Stuber-McEwen et al., 2009 ). Indeed, often, a reason why students enroll in online courses is the ease and convenience of an online format. However, if students become over-extended, they may use inappropriate resources and strategies to manage (e.g. Sterngold, 2004 ). In addition, the isolation that students may experience in an online course environment can also increase stress levels and lead them to be more prone to dishonest behaviors ( Gibbons et al., 2002 ).

Institutional Factors

Individual students are part of larger university culture. By some accounts, a primary contributor to academic dishonesty is the existence of a “cheating culture” ( Tolman, 2017 ). If a university has an established culture of cheating—or at least the perception of a culture of cheating—students may be tolerant of cheating, believe that cheating is necessary in order to succeed, and believe that all students are cheating ( Crittenden et al., 2009 ). Students directly shape cheating culture, and thus subsets of students in a university population may have their own cheating cultures ( Tolman, 2017 ). It is plausible, then, for online students to have their own cheating culture that differs from the rest of the student population. However, if this subset of students is identified as being at risk for academic dishonesty, there is the opportunity for the university to proactively address academic integrity in that student group ( Tolman, 2017 ).

We note, however, the peculiar situation of current the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for universities that transitioned to mostly online courses. A university’s cheating culture may change, as large numbers of students may be faced with increased pressures and as online courses are designed—and assessments developed—with atypical rapidity. It will be necessary for future research on university cheating culture, both on campus and online, to consider the potential long-term impacts of the pandemic on “appropriate” student behaviors. For example, there appear to be many new opportunities for students to share papers and coursework with peers in online forums. In some cases this sharing may be appropriate, whereas in others it may not. Determining effective methods for communication of boundaries related to academic honesty—especially when boundaries can vary depending on the nature of an assignment—will be especially important.

Institutional policies related to the academic standards of the university also impact academic honesty on campus. Some institutional policies may be too lax, with insufficient sanctions and penalization of academic dishonesty (e.g., Akbulut et al., 2008 ). Further, even when sanctions and penalization are adequate, a lack of knowledge of these policies within staff, administrators, and students—or insufficient effort made to inform students about these policies—can result in academic dishonesty (see also Jordan, 2001 ). For example, McCabe et al. (2002) found a significant correlation such that academic dishonesty decreased as students’ and staff’s perceived understanding and acceptance of academic integrity policies increased. Additionally, academic dishonesty was found to be inversely related to the perceived certainty of being reported for academic dishonesty and the perceived severity of the university’s penalties for academically dishonest behavior. Relatedly, universities with clear honor codes had lower academic dishonesty than universities without honor codes ( McCabe et al., 2002 ). Given these findings, universities should make academic conduct policies widely known and consider implementing honor codes to minimize the cheating culture(s). Specifically, for online courses, these findings suggest that the university’s academic conduct policies and honor codes should be directly stated on course sites.

Medium of Delivery

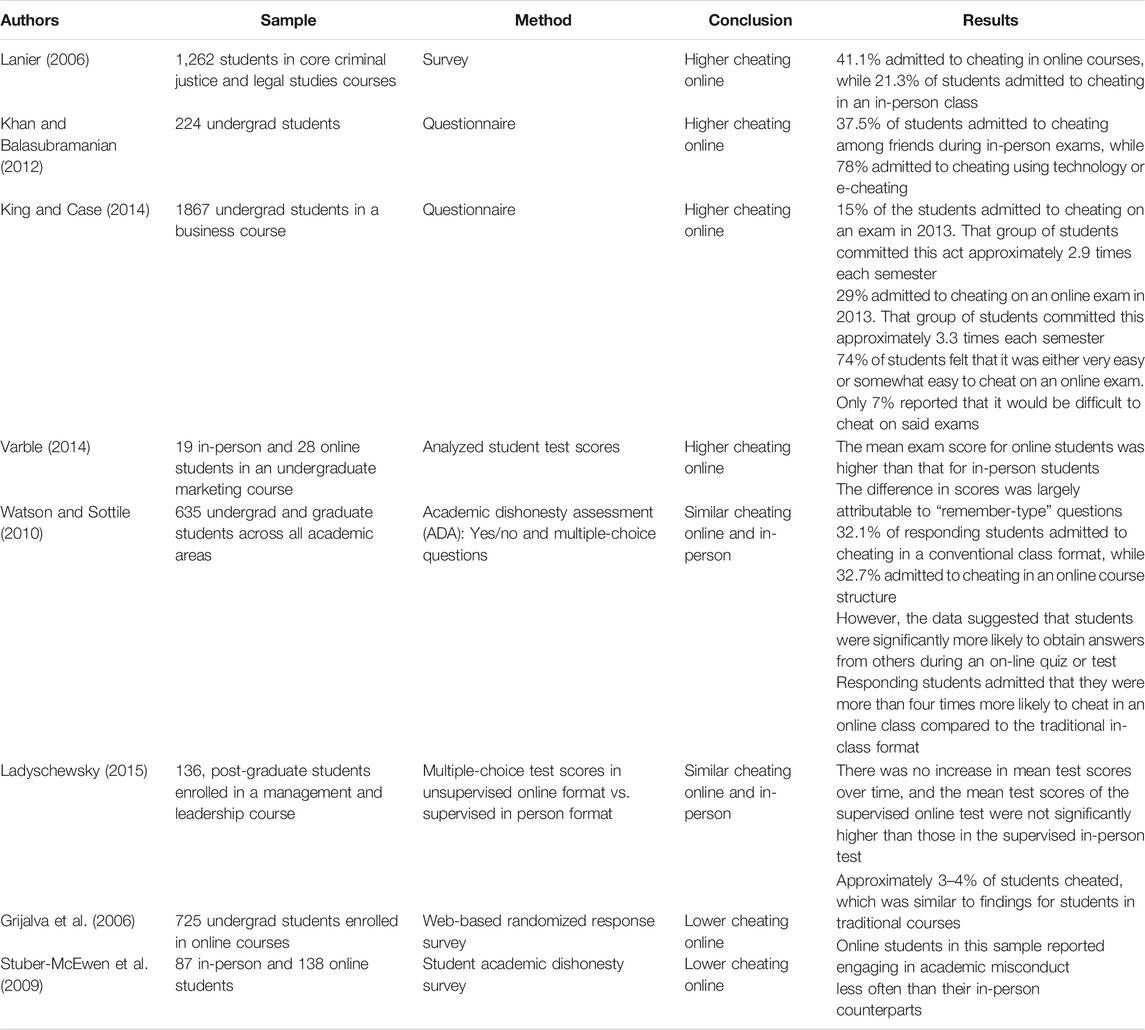

The belief that cheating occurs more often in online courses than in in-person courses—particularly for high-stakes assessments like exams—is widespread, with approximately 42–74% of students believing it to be easier to cheat in an online class ( King et al., 2009 ; Watson and Sottile, 2010 ). Thus, the question of whether students are cheating at greater rates in online classes is paramount in evaluating the reliability of online assessments as measurements of mastery in higher education. Though there have been many studies of academic dishonesty in in-person classes, few studies have attempted to compare cheating rates between in-person and online classes. In those that do, the results appear to be inconsistent with some studies demonstrating that cheating occurs more often in online classes than in in-person classes ( Lanier, 2006 ; Khan and Balasubramanian, 2012 ; King and Case, 2014 ; Watson and Sottile, 2010 ), others demonstrating equivalent rates of cheating ( Grijalva et al., 2006 ; Ladyshewsky, 2015 ), and some demonstrating that cheating occurs more often in-person ( Stuber-McEwen et al., 2009 ). Table 1 provides a summary of these studies, and we highlight some of them below.

TABLE 1 . Studies Comparing Academic Dishonesty in Online Classes and In-Person Classes .

Four studies to date have found cheating rates to be higher in online courses than in in-person courses. Lanier (2006) , for example, surveyed college students ( n = 1,262) in criminal studies and legal studies courses and found that 41.1% of respondents admitted to cheating in an online course while 21.3% admitted to cheating in an in-person course. The study also found some preliminary evidence for differences in cheating rates between majors, though the sample sizes for some groups were too low to be reliable: business majors were the most likely to cheat ( n = 6, 47.1%), followed by “hard sciences” ( n = 20, 42.6%), and “social sciences” ( n = 282, 30%). Though clearly tentative given the small sample sizes, these data suggest that there may be different cheating cultures that exist within universities, demonstrating the importance of considering group-level culture differences with respect to cheating ( Institutional Factors above). Further supporting an increased rate of cheating in online assessments, Khan and Balasubramanian (2012) surveyed undergraduate students attending universities in the United Arab Emirates ( N = 224) and found that students admitted to higher cheating rates using technology or e-cheating. Although this study did not differentiate between online and in-person course formats, it does suggest an increase in cheating via the use of online technology.

Using the Student Ethical Behavior instrument with undergraduate students enrolled in a business course ( n = 1867), King and Case (2014) found higher cheating rates in online exams than in in person-exams. Specifically, researchers found that 15% of students admitted to cheating on an in-person exam, at about 2.9 times a semester, while 29% admitted to cheating on an online exam, at about 3.3 times a semester. Thus, not only were students cheating at higher rates in online exams as compared to in-person exams, but those that did admit to cheating were also cheating more frequently during a semester. Consistent with this finding, Varble (2014) analyzed the test scores of students enrolled in an online or an in-person, undergraduate marketing course. Students took exams either online or in person. The study found higher mean test scores in the online test group with the exception of one test, than test scores in the in-person test group. The difference in scores was largely attributed to “remember” type questions which rely on a student’s ability to recall an answer, or alternatively, questions which could be looked up in unauthorized resources. Given these findings, Varble (2014) concluded that cheating may have taken place more often in the online tests than in-person tests.

In contrast to studies reporting increases in academic dishonesty in online assessments, other studies have found lower rates of cheating in online settings as compared to in-person. Grijalva et al. (2006) used a randomized response survey method with 725 undergraduate students taking an online course and estimated that only 3–4% of students cheated. Consistent with this finding, Stuber-McEwen et al. (2009) surveyed in-person ( n = 225) and online students ( n = 138) using the Student Academic Dishonesty Survey and found that online students reported engaging in less academic misconduct than in-person students. An important methodological feature to consider, however, is that the sample of online students consisted of more mature distance study learners than the in-person sample; this study may not be applicable to the general university population. 3

Although some studies have found cheating rates to be higher or lower in online classes, some have not found significant differences. Watson and Sottile (2010) , for example, used the Academic Dishonesty Assessment with a sample of undergraduate and graduate students from different faculties ( n = 635). The study found that 32.7% of respondents admitted to cheating in an online course while 32.1% admitted to cheating in an in-person course. However, the data also demonstrated that students were significantly more likely to cheat by obtaining answers from others during an online quiz or test than in an in-person quiz or test (23.2–18.1%) suggesting that students in an online course tended to cheat more in an online exam, while students in an in-person course tended to cheat through other assignments. Additionally, students admitted that they were four times more likely to cheat in an online class in the future compared to an in-class format (42.1–10.2%) ( Watson and Sottile, 2010 ). This study points to a potential importance of addressing cheating particularly in online exams in order to ensure academic honesty in online courses, though we note that Ladyschewsky (2015) found that in a sample of post-graduate students ( n = 136), multiple-choice test scores in an unproctored online format were not different from scores from a proctored, in-person exam.

Assessment-specific Factors

Research varies in the context in which cheating is explored. For example, some studies examine cheating within some or all types of online assessments, whereas others specifically focus on exams. The type of assessment likely matters when it comes to academic behaviors. For example, though Lanier (2006) found higher reporting of cheating in online courses, the study did not distinguish among assessments, and instead focused on cheating across all assignments in classes. Yet, in Watson and Sottile (2010) ; described above, students were significantly more likely to cheat by obtaining answers from others during an online quiz or test than in an in-person quiz or test (23.2–18.1%), suggesting that students in an online course tended to cheat more in an online exam, while students in an in-person course tended to cheat through other assignments.

If students are more likely to engage in academic dishonesty on high-stakes summative assessments (e.g., exams) rather than formative assessments throughout the term—and if online exams offer more opportunities for dishonesty—then rates of cheating would be expected to differ depending on the assessment type. Additionally, when comparing dishonesty in online and on-campus courses, the differences might be minimal in relation to assessments that allow for plagiarism (e.g., essays that may be completed “open book” over an extended time period; e.g., Watson & Sottile, 2010 ). We thus encourage future research to consider the type of assessment when comparing cheating in online vs. in-person course environments.

Methods for Reducing Academic Dishonesty in Online Assessment

Just as the reasons for why students cheat are varied, so too are methods for reducing academic dishonesty. We again organize the topic in relation to factors related to the individual student, the institution, the medium of delivery, and the assessments themselves. Throughout, we focus primarily on summative assessments that may have various formats, from multiple-choice questions to take-home open-book essays. Though the methods for preventing cheating are discussed separately from the reasons why students cheat in this paper, we emphasize that the methods must be considered in concert with consideration of the reasons and motivations that students may engage in academic dishonesty in the first place.

Individual- and Institutional-Level Methods

We discuss both individual- and university-level methods to reduce academic dishonesty together here, as current methods consider the bi-directional influence of each level. As highlighted in Institutional Factors , institutional factors that can increase academic dishonesty include lax or insufficient penalization of academic dishonesty, insufficient knowledge of policies and standards across students, instructors, and administrators, and insufficient efforts to inform students about these policies and standards ( Akbulut et al., 2008 ; Jordan, 2001 ). In order to ensure academic honesty at universities, administrators and staff must clearly define academic dishonesty and what behaviors are considered academically dishonest. Students often demonstrate confusion about what constitutes academic dishonesty, and without a clear definition, many students may cheat without considering their behaviors to be academically dishonest. Thus, the more faculty members discuss academic honesty, the less ambiguity students will have when confronting instances of academic dishonesty ( Tatum and Schwartz, 2017 ). In addition to making students aware of what constitutes academic dishonesty, it is also important to make students aware of the penalties that exist for academically dishonest behavior. Academic dishonesty is inversely related to the perceived severity of the university’s penalties for academically dishonest behavior ( McCabe et al., 2002 ). When faculty members are aware of their institutions policies against academic dishonesty and address all instances of dishonesty, fewer academically dishonest behaviors occur ( Boehm et al., 2009 ).

Faculty and staff can influence the cheating culture of their university simply by discussing the importance of academic honesty with their students. These discussions can help shape and change a student’s beliefs on cheating, hopefully reducing their ability to rationalize academically dishonest behavior. Discussions with students on the importance of academic honesty may help reduce feelings of overestimated cheating frequency among peers, and may prevent students from rationalizing cheating behavior. Honor codes, for example, are effective at reducing academic dishonesty when they clearly identify ethical and unethical behavior ( Jordan, 2001 ; McCabe and Trevino, 1993 ; McCabe and Trevino, 1996 ; McCabe et al., 2001 ; McCabe et al., 2002 ; Schwartz et al., 2013 ), and are associated with perceptions of lower cheating rates among peers ( Arnold et al., 2007 ; Tatum and Schwartz, 2017 ). Further, these codes reduce students’ ability to rationalize cheating ( Rettinger and Kramer, 2009 ), increase the likelihood that faculty members and students will report violations ( Arnold et al., 2007 ; McCabe and Trevino, 1993 ), and increase the perceived severity of sanctions ( McCabe and Trevino, 1993 ; Schwartz et al., 2013 ). In addition to implementing honor codes school-wide, honor codes can also be implemented into specific courses and have been shown to reduce cheating and improve communication between students and faculty by increasing feelings of trust and respect among the students ( Konheim-Kalkstein, 2006 ; Konheim-Kalkstein et al., 2008 ).

Methods in Relation to the Medium of Delivery

Multiple methods to combat academic dishonesty in online assessments focus on the manner in which the assessment is delivered and invigilated. One view is that an in-person proctored, summative exam at a testing center is the best practice for an otherwise online course because of the potential ease of cheating in an unproctored environment or an online-proctored environment ( Edling, 2000 ; Rovai, 2000 ; Deal, 2002 ). Another view is that with the correct modifications and security measures, online exams offer a practical solution for students living far from campus or other testing facilities while still maintaining academic integrity. However, both proposed solutions come with their own disadvantages. Requiring students to travel to specific exam sites may not be feasible for remote students, and hiring remote proctors can be expensive ( Rosen and Carr, 2013 ). Indeed, in the current context of the global COVID-19 pandemic, in-person proctoring has been unfeasible in many regions.

In Methods in Relation to the Medium of Delivery , we focus on methods that do not require in-person proctoring. The assessment type we focus on is the summative exam, though we note the variability in the style that such assessments can take. There are currently various means of detecting cheating in online exams, and we have chosen to discuss these means of detection separately from methods use to prevent cheating as the implementation tends to occur at a different level and for a different purpose (e.g., technological systems that detect cheating while it is occurring or shortly after, rather than solutions at the level of assessment format that are designed to promote academic integrity). However, we do note that if students are aware of the cheating detection systems in place, the systems may have a preventative effect.

Online Cheating Detection

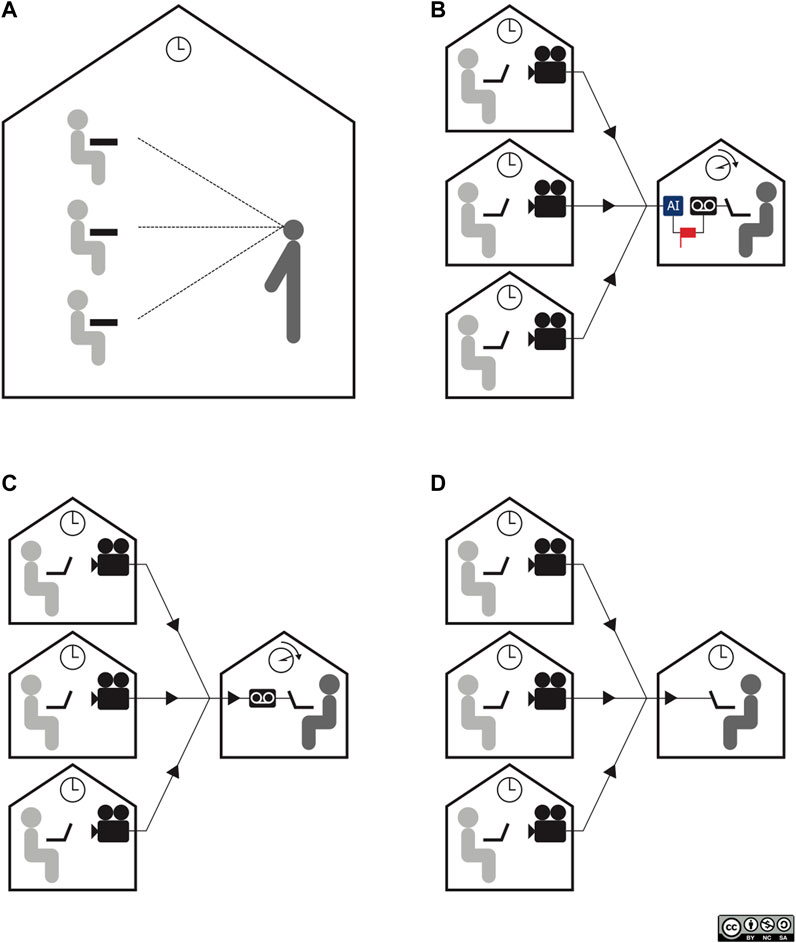

The exam cheating detection systems described below have been developed, in part, because holding exams in-person at a registered location with live proctors is often not feasible due to financial, travel, or other logistical reasons ( Cluskey et al., 2011 ). The general types of online proctoring include video summarization, web video recording, and live online proctoring; each is described below and in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1 . Four types of proctoring: (A) in-person, (B) video summarization, (C) web video recording, and (D) live online proctoring.

Though online proctoring provides some intuitive advantages for detecting cheating behaviours, and it maps closely onto familiar face-to-face proctoring processes, many have raised concerns in media outlets about both the ethics and efficacy of these systems. For example, concerns have been raised about student invasion of privacy and data protection (e.g., Dimeo, 2017 ; Lawson, 2020 ), and breeches have occurred (e.g., Lupton, 2020 ). In addition to concerns related to privacy, cases have been reported where students were discriminated against by a proctoring software as a result of their skin colour (e.g., Swauger, 2020 ). Not only are there concerns about ethics regarding online proctoring software, but there are also concerns about whether these methods are even effective, and if so, for how long. For example, there have long been readily available guides that demonstrate how to “cheat” the cheating software (e.g., Binstein, 2015 ). If an instructor deems online proctoring effective and necessary, prior to using online proctoring, instructors should explicitly consider whether students are treated justly and equitably, just as they should in any interaction with students. Instructors are also encouraged to carefully investigate privacy policies associated with online cheating detection software, and any applicable institution policies (e.g., data access and retention policies), prior to using such technology.

Video Summation

Video summarization software, also referred to as video abstraction , utilizes artificial intelligence to detect cheating events that may occur during the exam ( Truong and Venkatesh, 2007 ). Students are video recorded using their own webcam throughout the exam. If a cheating event is detected, the program will flag the video for future viewing by a proctor. Thus, the time demands of proctors are reduced, yet students are monitored. Video summarization programs can generate either keyframes (a collection of images extracted from the video source) or video skims (video segments extracted from the video source) to represent potential cheating behavior (e.g. Truong and Venkatesh, 2007 ). Both of these forms convey the potential cheating event in order for future determination by a human proctor. However, video skims have an advantage over keyframes in that they have an ability to include audio and motion elements which convey pertinent information in the process of invigilation ( Cote et al., 2016 ).

The main advantage of choosing an invigilation service like this one is that it reduces the hours that proctors must put in into invigilating the exam. However, detecting cheating behavior without live human interaction is a difficult process. Modeling suspicious behavior is complex in that cheating behavior does not typically follow a pattern or type, thus making it difficult to recognize accurately ( Cote et al., 2016 ). Therefore, some suspicious activity may not be detected, and administrators may not be able to guarantee that all cheating behavior has been deterred or detected. Further, there is no opportunity for a live proctor to intervene or gather more information if atypical behaviour is occurring, limiting the ability to mitigate a violation of academic integrity if it is occurring, or about to occur.

Web Video Recording

In relation to online exams, web video recording refers to situations in which the student is video recorded throughout the entirety of the exam for later viewing by an instructor. Like video summarization methods, detection software can be used in order to flag any suspicious activity for later viewing. Administrators and instructors may feel more confident in this service as they can view the entire exam, not only the flagged instances. However, reviewing all exams individually may not be feasible, and most exams are not reviewed in full. Unlike video summarization programs, web video recording programs do not have specific proctors review all flagged instances, and instead rely on review by the administrators and instructors themselves. Knowing that the recording is occurring may deter students, but as with detection based on artificial intelligence, it is not guaranteed that all cheating behavior will be detected. It is important to note that with this method, as with the previous method, there is no opportunity for intervention by a proctor if an event is flagged as a possible violation of academic integrity. Thus, there may be ambiguous situations that have been flagged electronically with no opportunity to further investigate, and missed opportunities for prevention.

Live Online Proctoring

The final type of online proctoring, and arguably the most rigorous, is referred to as live online proctoring or web video conference invigilation . This method uses the student’s webcam and microphone to allow a live-proctor to supervise students during an online exam. Services can range from one-on-one invigilation sessions to group invigilation sessions where one proctor is supervising many students. Many administrators may feel the most comfortable using this kind of service as it is closest to an in-person invigilated exam. However, even with a live proctor supervising the student(s), cheating behavior can go undetected. At the beginning of a session, students are typically required to show their testing environment to their proctor; however, cheating materials can be pulled out during an exam unnoticed in the surrounding environment. If the proctor does not suspect cheating behaviors, they will not request another view of the entire room. Live online proctoring is also typically the most expensive of the options.

Online Cheating Detection: Other Solutions

Though online proctoring is one method for cheating detection, others also exist. Just as with online proctoring, instructors are encouraged to understand all applicable policies prior to using detection methods. Challenge questions, biometrics, checks for text originality, and lockdown browsers, are currently available technological options that instructors and institutions might consider.

Challenge Questions

Challenge or security questions are one of the simplest methods for authenticating the test taker. This method requires personal knowledge to authenticate the student and is referred to as a ‘knowledge-based authentication’ method ( Ullah et al., 2012 ). Students are asked multiple choice questions based on their personal history, such as information about their past home addresses, name of their high school, or mother(s) maiden name ( Barnes and Paris, 2013 ). Students must answer these questions in order to access the exam, and the questions may also be asked randomly during the assessment ( Barnes and Paris, 2013 ). These questions are often based on third-party data using data mining systems ( Barnes and Paris, 2013 ; Cote et al., 2016 ) or can be entered by a student on initial log-in before any examination. When a student requests an examination, the challenge questions are generated randomly from the initial profile set-up questions or third-party information, and answers are compared in order to verify the student’s identity ( Ullah et al., 2012 ). This relatively simple method can be used for authenticating the test taker; however, it cannot be used to monitor student behavior during the exam. Additionally, students may still be able to bypass the authentication process by providing answers to others to have another person take the exam, or to collaborate with others while taking the test. Thus, if chosen, this method should be used in concert with other test security methods in order to ensure academic honesty.

The use of biometrics, the measurement of physiological or behavioral features of an individual, is an authentication method that allows for continuous identity verification ( Baca and Rabuzin, 2005 ; Cote et al., 2016 ). This method of authentication compares a registered biometric sample against the newly captured biometrics in order to identify the student ( Podio and Dunn, 2001 ). When considering the use of biometric data, potential bias in identification, data security, and privacy must be carefully considered. It may be that the risks associated with the use of biometric data, given the intimate nature of these data, outweigh the benefits for an assessment.

There are two main types of biometric features: those that require direct physical contact with a scanner, such as a fingerprint, and those that do not require physical contact with a scanner such as hair color ( Rabuzin et al., 2006 ). Biometrics commonly use “soft” traits such as height, weight, age, gender, and ethnicity, physiological characteristics such as eyes, and face, and behavior characteristics such as keystroke dynamics, mouse movement, and signature ( Cerimagic and Rabiul Hasan, 2019 ). Combining two or more of the above characteristics improves the recognition accurateness of the program and is necessary to ensure security ( Cerimagic and Rabiul Hasan, 2019 ; Rabuzin et al., 2006 ).

Biometric-based identification is often preferred over other methods because a biometric feature cannot be faked, forgotten, or lost, unlike passwords and identification cards ( Prabhakar and Jain, 2002 ; Rudrapal et al., 2012 ). However, the biometric features that are considered should be universal, unique, permanent, measurable, accurate, and acceptable ( Frischholz and Dieckmann, 2000 ). Specifically, ideal biometric features should be permanent and inalterable, and the procedure of gathering features must be inconspicuous and conducted by devices requiring little to no contact. Further, the systems are ideally automated, highly accurate, and operate in real time ( Jain et al., 1999 ). However, no biometric feature to date meets all of the above criteria to be considered ideal, thus, it is important to measure multiple features in order to get the most accurate verification of identity (see Rabuzin et al., 2006 for an overview of all biometric features). Multimodal biometric systems use several biometric traits and technologies at the same time in order to verify the identity of the user ( Rabuzin et al., 2006 ). The multimodal system tends to be more accurate, as combining two or more features improves recognition accurateness ( Cerimagic and Rabiul Hasan, 2019 ).

Fingerprint recognition is one of the most broadly used biometric features as it is a unique identifier ( Aggarwal et al., 2008 ) and has a history of use in many different professional fields, most notably by the police. Additionally, fingerprints have become a commonly used identifier for personal handheld devices like phones. However, the use of fingerprint biometrics for student identification during online examinations can require additional resources such as fingerprint scanners, cellphones equipped with fingerprint technology, or other software at the student’s location, which may limit its current practicality ( Ullah et al., 2012 ). Similarly, face recognition uses image recognition and pattern matching algorithms to authenticate the student’s identity ( Zhao and Ye, 2010 ). This biometric is also good candidate for online exams; however, it may not always be reliable due to the complexity of recognition technology and variability in lighting, facial hair, and facial features ( Agulla et al., 2008 ; Ullah et al., 2012 ).

Audio or voice biometrics are used for speech recognition as well as authentication of the speaker. Human voice can be recognized via an automated system based on speech wave data ( Ullah et al., 2012 ). A voice biometric is highly unique, in fact it is as unique to an individual as a fingerprint ( Rudrapal et al., 2012 ). However, as with facial recognition, varying conditions such as speech speed, environmental noises, and the quality of recording technology may result in unreliable verification ( Ullah et al., 2012 ). Finally, the analysis of an individual’s typing patterns (e.g., error patterns, speed, duration of key presses) can be used to authenticate the user ( Bartlow and Cukic, 2009 ).

Checks for Text Originality

When using assessments that require a written answer, software that checks for the originality of text (such as “TurnItIn”) can help to identify work that was taken from sources without proper citation. With this method, submitted work is compared against other work held in the software’s bank to check for originality. Benefits of this method include being able to compare submitted work against work that is publicly available (as defined by the software company) to check for important degrees of overlap, as well as comparing submitted work against other assignments that have been previously submitted.

Although checking for text originality can be helpful in detecting both accidental and intentional plagiarism, there are concerns about the ethics of this practice, including copyright infringement of student work (e.g., Horovitz, 2008 ). Instructors are typically able to specify within the software whether submitted work will be stored for later comparisons (or not), and this information, along with the broader use policies, should be included specifically in the syllabus or other relevant communications with students. Additionally, when using originality-checking software, it is important to know that high overlap with other works is not necessarily indicative of plagiarized work, and there can be high rates of false positives. For example, submissions with high rates of appropriate references can return a high score for overlap simply because those references are standard across many works. Thus, instructors should refer to the full originality report so that they can use judgment as to whether high scores are actually reflective of plagiarism.

Lockdown Browsers

Lockdown browsers prevent the use of additional electronic materials during exams by blocking students from visiting external websites or using unauthorized applications on the same device as the one being used to take the assessment ( Cote et al., 2016 ). These programs take control of the entire computer system by prohibiting access to the task manager, copy and paste functions, and function keys on that device ( Percival et al., 2008 ). Though likely helpful, lockdown browsers cannot guarantee that external information will not be accessed. Students may still access information using another computer, a cell phone, class notes, etc., during an assessment. In addition to using external material, students may also cheat by making the lockdown browser program inoperative ( Percival et al., 2008 ). For these reasons, it is proposed that these programs should be used in concert with other exam security measures in order to prevent and detect cheating behaviors during exams.

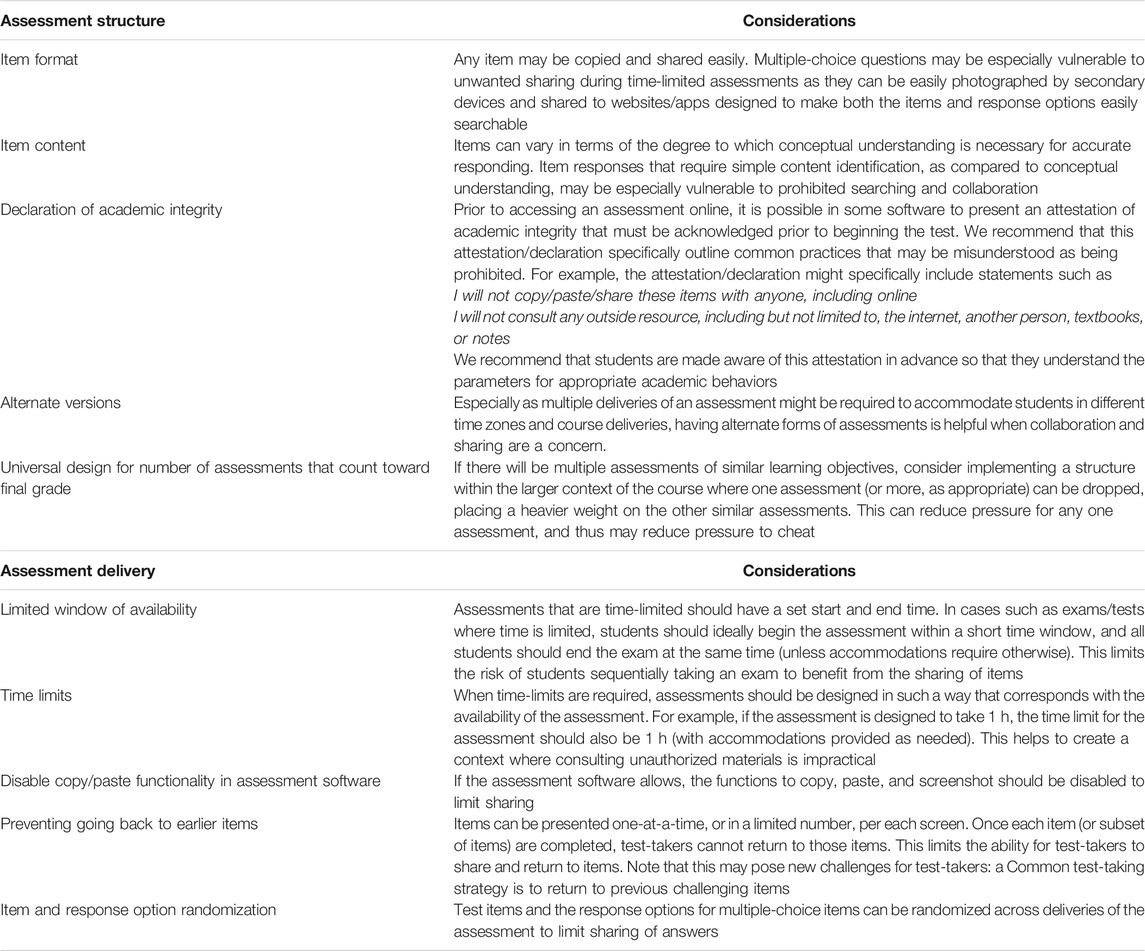

Assessment-Based Methods

Given the financial and logistical concerns that may make cheating detection through online proctoring and other technological solutions unfeasible (e.g. Cluskey et al., 2011 ), and given concerns with privacy and data security, some advocate instead for changes to exam formatting (structure, presentation) that can, in turn, prevent and deter cheating at little cost ( Vachris, 1999 ; Shuey, 2002 ; , 2003 ). Below and in Table 2 , we highlight considerations for both assessment structure and assessment presentation, with particular focus on online exams, that may promote academic integrity behaviors. It is also important to note that many of these considerations are closely related, and many of these work in tandem to facilitate an honest assessment.

TABLE 2 . Preventing cheating and facilitating academic integrity through assessment structure and presentation.

The considerations provided in Table 2 have been discussed at length by other scholars. For example, Cluskey et al. (2011) have proposed online exam control procedures (OECPs), or non-proctor alternatives, to promote academic honesty. These OECPs include: offering exams at one set time, offering an exam for a brief period of time, randomizing the question sequence, presenting only one question at a time, designing the exam to occupy a limited period of time allowed for the exam, allowing access to the exam only one time, requiring the use of a lockdown browser, and changing at least one third of exam questions every term. These methods will likely not eliminate cheating entirely; however, the inclusion of these methods may decrease rates of cheating.

Ideally, online assessments are designed in such a way to reduce academic dishonesty through exam format by reducing the opportunity, incentive/pressure , and the rationalization/attitude for cheating. As discussed previously, the academic fraud triangle posits that all three of these factors lead to academic dishonesty ( Ramos, 2003 ; Becker et al., 2006 ; Varble, 2014 ). Thus, in relation to online exams, minimizing these factors may serve to encourage academic honesty. Though many of the procedures described below work well in tandem, of course, some of these procedures are incompatible with one another; for example, limiting the number of exam attempts may limit the opportunity to cheat, but allowing for multiple exam attempts may reduce the pressure to cheat. We suggest that it is important to consider a balance; cheating prevention methods will be limited in their success if students’ needs or attitudes have not also been addressed with the methods described in Individual- and Institutional-Level Methods .

This paper began by providing a review of current thought regarding the reasons why students may feel motivated to engage in behaviors that violate academic integrity. We approached this question by considering four “levels” from which to consider academic integrity: the student, the institution, the medium of delivery, and the assessment. We suggest that when examining academic integrity in the online environment, it will be necessary for continued research exploring cheating culture and the nature of, and motivation for, cheating on different types of assessments. Further, as shown, research to date has produced mixed findings in relation to whether academic dishonesty may be more or less prevalent in the online environment, and we have called for further research that examines assessment type, field of study, and student demographics (e.g., age and reason for enrolling in the course). In the latter half of this review, we detailed methods for both preventing and detecting cheating behavior, with a focus on online summative assessments. We emphasize again, though, that these methods must be considered in concert with broader consideration of the reasons and motivations that students may engage in academic dishonesty in the first place, and with explicit attention and care to student privacy and fair treatment.

Academic integrity remains an integral element of higher education. The principle values that constitute academic integrity not only uphold the reputation of a university and the value and meaning of the degrees it confers, but they also create a shared framework for professional work that is extended beyond the academy. Thus, as online studies continue to expand in post-secondary education, we believe that it will be important to have evolving scholarship and discussion regarding the maintenance of academic integrity in the online environment.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived of and outlined the project. OH completed the majority of the literature review and wrote the first draft. MN and VK added to the literature review and edited subsequent drafts.

This work was supported by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to VK. MN is the current Undergraduate Chair, and VK was the past Associate Head (Teaching and Learning), of the Department of Psychology at Queen’s University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Queen’s University is situated on traditional Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee Territory.

1 As a supplement to this paper, we have made two infographics available via https://osf.io/46eh7/ with a Creative Commons licence allowing reuse and distribution with attribution.

2 Given that the literature reviewed for this paper often uses the terms “academic dishonesty," “departures from academic integrity," and “cheating” interchangeably, this paper will follow this convention and not attempt to distinguish these terms.

3 In typical research conducted on academic dishonesty across online and in-person mediums, researchers define their samples as consisting of “undergraduate” and/or “graduate” students. An important consideration for future research is to specify the age ranges of the sample. It is possible that the frequency and type of cheating behavior by mature, nontraditional students and by traditional students may differ. One might hypothesize that mature students may be less motivated or have fewer opportunities to cheat than traditional students.

Aggarwal, G., Ratha, N. K., Jea, T., and Bolle, R. M. (2008). “Gradient Based Textural Characterization of Fingerprints,” in Paper Presented at the 2008 IEEE Second International Conference on Biometrics: Theory, Applications and Systems (Washington, DC, USA: IEEE ). doi:10.1109/BTAS.2008.4699383

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Agulla, E. G., Anido-Rifón, L., Alba-Castro, J. L., and García-Mateo, C. (2008). “Is My Student at the Other Side? Applying Biometric Web Authentication to E-Learning Environments,” in Paper Presented at the Eighth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (Santander, Cantabria, Spain: IEEE ). doi:10.1109/icalt.2008.184

Akbulut, Y., Şendağ, S., Birinci, G., Kılıçer, K., Şahin, M. C., and Odabaşı, H. F. (2008). Exploring the Types and Reasons of Internet-Triggered Academic Dishonesty Among Turkish Undergraduate Students: Development of Internet-Triggered Academic Dishonesty Scale (ITADS). Comput. Edu. 51 (1), 463–473. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2007.06.003

Allen, I. E., and Seaman, J. (2017). Digital Learning Compass: Distance Education Enrollment Report 2017 . Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group, e-Literate, and WCET . Available at: https://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/digtiallearningcompassenrollment2017.pdf .

Allen, I., and Seaman, J. (2010). Class Differences: Online Education in the United States, 2010 . Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group, Babson College . doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.a2084780

CrossRef Full Text

Antion, D. L., and Michael, W. B. (1983). Short-term Predictive Validity of Demographic, Affective, Personal, and Cognitive Variables in Relation to Two Criterion Measures of Cheating Behaviors. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 43, 467–482. doi:10.1177/001316448304300216

Arnold, R., Martin, B. N., and Bigby, L. (2007). Is There a Relationship between Honor Codes and Academic Dishonesty? J. Coll. Character 8 (2). doi:10.2202/1940-1639.1164

Baca, M., and Rabuzin, K. (2005). “Biometircs in Network Security,” in Paper Presented at the XXVIII International Convention MIPRO (Rijeka, Croatia: IEEE ).

Google Scholar

Barnes, C., and Paris, B. (2013). An Analysis of Academic Integrity Techniques Used in Online Courses at A Southern University. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264000798_an_analysis_of_academic_integrity_techniques_used_in_online_courses_at_a_southern_university .

Bartlow, N., and Cukic, B. (2009). “Keystroke Dynamics-Based Credential Hardening Systems,” in Handbook of Remote Biometrics: For Surveillance and Security . Editors M. Tistarelli, S. Z. Li, and R. Chellappa (London: Springer ), 328–347.

Becker, D., Connolly, J., Lentz, P., and Morrison, J. (2006). Using the Business Fraud triangle to Predict Academic Dishonesty Among Business Students. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 10 (1), 37–52.

Binstein, J. (2015). On Knuckle Scanners and Cheating – How to Bypass Proctortrack, Examity, and the Rest. Available at: https://jakebinstein.com/blog/on-knuckle-scanners-and-cheating-how-to-bypass-proctortrack/ .

Boehm, P. J., Justice, M., and Weeks, S. (2009). Promoting Academic Integrity in Higher Education. Community Coll. Enterprise 15, 45–61.

Cerimagic, S., and Hasan, M. R. (2019). Online Exam Vigilantes at Australian Universities: Student Academic Fraudulence and the Role of Universities to Counteract. ujer 7 (4), 929–936. doi:10.13189/ujer.2019.070403

Christe, B. (2003). Designing Online Courses to Discourage Dishonesty. Educause Q. 26 (4), 54–58.

Cluskey, J., Ehlen, C., and Raiborn, M. (2011). Thwarting Online Exam Cheating without proctor Supervision. J. Acad. Business Ethics 4.

Cote, M., Jean, F., Albu, A. B., and Capson, D. (2016). “Video Summarization for Remote Invigilation of Online Exams,” in Paper Presented at the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) ( IEEE ). doi:10.1109/wacv.2016.7477704

Crittenden, V. L., Hanna, R. C., and Peterson, R. A. (2009). The Cheating Culture: a Global Societal Phenomenon. Business Horizons 52, 337–346. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.02.004

Crown, D. F., and Spiller, M. S. (1998). Learning from the Literature on Collegiate Cheating: A Review of Empirical Research. J. Business Ethics 18, 229–246. doi:10.1023/A:1017903001888

Deal, W. F. (2002). Distance Learning: Teaching Technology Online. (Resources in Technology). Tech. Teach. 61 (8), 21, 2020. Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A87146664/AONE?u=queensulaw&sid=AONE&xid=0d728309 .

DeVoss, D., and Rosati, A. C. (2002). "It Wasn't Me, Was it?" Plagiarism and the Web. Comput. Compost. 19, 191–203. doi:10.1016/s8755-4615(02)00112-3

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., Williams, L. E., Francis, B., and Haines, V. J. (1996). College Cheating: Ten Years Later. Res. High Educ. 37 (4), 487–502. doi:10.1007/bf01730111Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/40196220 .

Dimeo, J. (2017). Online Exam Proctoring Catches Cheaters, Raises Concerns . Washington, DC: Inside Higher . doi:10.6028/nist.sp.1216 Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2017/05/10/online-exam-proctoring-catches-cheaters-raises-concerns .

Edling, R. J. (2000). Information Technology in the Classroom: Experiences and Recommendations. Campus-Wide Info Syst. 17 (1), 10–15. doi:10.1108/10650740010317014

Fishman, T. (2014). The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity . Second Edition (International Center for Academic Integrity). Available at: https://www.academicintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Fundamental-Values-2014.pdf .

Frankl, G., Schartner, P., and Zebedin, G. (2012). “Secure Online Exams Using Students' Devices,” in Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (Marrakech, Morocco: EDUCON ). doi:10.1109/EDUCON.2012.6201111

Frischholz, R. W., and Dieckmann, U. (2000). BiolD: a Multimodal Biometric Identification System. Computer 33, 64–68. doi:10.1109/2.820041

Gibbons, A., Mize, C., and Rogers, K. (2002). “That's My Story and I'm Sticking to it: Promoting Academic Integrity in the Online Environment,” in Paper Presented at the EdMedia + Innovate Learning 2002 (Denver, Colorado, USA: Reports - Evaluative; Speeches/Meeting Papers ). doi:10.3386/w8889Available at: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/10116 .

Grijalva, T., Nowell, C., and Kerkvliet, J. (2006). Academic Honesty and Online Courses. Coll. Student J. 40 (1), 180–185.

Hard, S. F., Conway, J. M., and Moran, A. C. (2006). Faculty and College Student Beliefs about the Frequency of Student Academic Misconduct. J. Higher Edu. 77 (6), 1058–1080. doi:10.1353/jhe.2006.0048

Harmon, O. R., and Lambrinos, J. (2008). Are Online Exams an Invitation to Cheat?. J. Econ. Edu. 39 (2), 116–125. doi:10.3200/jece.39.2.116-125

Horovitz, S. J. (2008). Two Wrongs Don't Negate a Copyright: Don't Make Students Turnitin if You Won't Give it Back. Fla. L. Rev. 60 (1). 1.

Hylton, K., Levy, Y., and Dringus, L. P. (2016). Utilizing Webcam-Based Proctoring to Deter Misconduct in Online Exams. Comput. Edu. 92-93, 53–63. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.002

Jain, A., Bolle, R. M., and Pankanti, S. (1999). Biometrics: Personal Identification in Networked Society . New York, NY: Springer .

Jaschik, S., and Lederman, D. (2018). 2018 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology: A Study by inside Higher Ed and Gallup . Washington, DC . Gallup, Inc. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/system/files/media/IHE_2018_Survey_Faculty_Technology.pdf .

Johnson, N. (2019). Tracking Online Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges: National Survey of Online and Digital Learning 2019 National Report . Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. Available at: http://www.cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2019_national_en.pdf .

Jordan, A. E. (2001). College Student Cheating: The Role of Motivation, Perceived Norms, Attitudes, and Knowledge of Institutional Policy. Ethics Behav. 11 (3), 233–247. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb1103_3

Jung, I. Y., and Yeom, H. Y. (2009). Enhanced Security for Online Exams Using Group Cryptography. IEEE Trans. Educ. 52 (3), 340–349. doi:10.1109/te.2008.928909

Kennedy, K., Nowak, S., Raghuraman, R., Thomas, J., and Davis, S. F. (2000). Academic Dishonesty and Distance Learning: Student and Faculty Views. Coll. Student J. 34, 309–314.

Khan, Z., and Balasubramanian, S. (2012). Students Go Click, Flick and Cheate-Cheating, Technologies, and More. J. Acad. Business Ethics 6, 1–26.

King, D. L., and Case, C. J. (2014). E-cheating: Incidence and Trends Among College Students. Issues Inf. Syst. 15 (I), 20–27.

King, C., Guyette, R., and Piotrowski, C. (2009). Online Exams and Cheating: An Empirical Analysis of Business Students' Views. Jeo 6. doi:10.9743/JEO.2009.1.5

Kitahara, R. T., and Westfall, F. (2007). Promoting Academic Integrity in Online Distance Learning Courses. J. Online Learn. Teach. 3 (3), 12.

Konheim-Kalkstein, Y. L., Stellmack, M. A., and Shilkey, M. L. (2008). Comparison of Honor Code and Non-honor Code Classrooms at a Non-honor Code university. J. Coll. Character 9, 1–13. doi:10.2202/1940-1639.1115

Konheim-Kalkstein, Y. L. (2006). Use of a Classroom Honor Code in Higher Education. J. Credibility Assess. Witness Psychol. 7, 169–179.

Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2015). Post-graduate Student Performance in 'supervised In-Class' vs. 'unsupervised Online' Multiple Choice Tests: Implications for Cheating and Test Security. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 40 (7), 883–897. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.956683

Lanier, M. M. (2006). Academic Integrity and Distance Learning∗. J. Criminal Justice Edu. 17, 244–261. doi:10.1080/10511250600866166

Lawson, S. (2020). Are Schools Forcing Students to Install Spyware that Invades Their Privacy as a Result of the Coronavirus Lockdown? Forbes. Available at: https://www.Forbes.com/sites/seanlawson/2020/04/24/are-schools-forcing-students-to-install-spyware-that-invades-their-privacy-as-a-result-of-the-coronavirus-lockdown/?sh=7cc680e5638d .

Lupton, A. (2020). Western Students Alerted about Security Breach at Exam Monitor ProctortrackCBC News Online. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/western-students-alerted-about-security-breach-at-exam-monitor-proctortrack-1.5764354 .

McCabe, D. L., and Trevino, L. K. (1993). Academic Dishonesty. J. Higher Edu. 64 (5), 522–538. doi:10.1080/00221546.1993.11778446

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., and Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Cheating in Academic Institutions: A Decade of Research. Ethics Behav. 11 (3), 219–232. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb1103_2

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., and Butterfield, K. D. (2002). Honor Codes and Other Contextual Influences on Academic Integrity: A Replication and Extension to Modified Honor Code Settings. Res. Higher Edu. 43 (3), 357–378. doi:10.1023/A:1014893102151

McCabe, D. L., and Trevino, L. K. (1996). What We Know about Cheating in CollegeLongitudinal Trends and Recent Developments. Change Mag. Higher Learn. 28 (1), 28–33. doi:10.1080/00091383.1996.10544253

Mecum, M. (2006). “Self-reported Frequency of Academic Misconduct Among Graduate Students,” in Paper Presented at the 26th Annual Convention of the Great Plains Students’ Psychology Convention (Warrensburg, MO: IEEE ).

Moten, J., Fitterer, A., Brazier, E., Leonard, J., and Brown, A. (2013). Examining Online College Cyber Cheating Methods and Prevention Measures. Electron. J. e-Learning 11, 139–146.

Namlu, A. G., and Odabasi, H. F. (2007). Unethical Computer Using Behavior Scale: A Study of Reliability and Validity on Turkish university Students. Comput. Edu. 48 (2), 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2004.12.006

Percival, N., Percival, J., and Martin, C. (2008). “The Virtual Invigilator: A Network-Based Security System for Technology-Enhanced Assessments,” in Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science (San Francisco, CA, USA: Newswood Limited ).

Podio, F. L., and Dunn, J. S. (2001). Biometric Authentication Technology: From the Movies to Your Desktop. doi:10.6028/nist.ir.6529 Available at: https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=151524

Prabhakar, S., and Jain, A. K. (2002). Decision-level Fusion in Fingerprint Verification. Pattern Recognition 35 (4), 861–874. doi:10.1016/S0031-3203(01)00103-0

Rabuzin, K., Baca, M., and Sajko, M. (2006). “E-learning: Biometrics as a Security Factor,” in Paper Presented at the 2006 International Multi-Conference on Computing in the Global Information Technology .

Ramos, M. (2003). Auditors’ Responsibility for Fraud Detection. J. Accountancy 195 (1), 28–35.

Rettinger, D. A., and Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and Personal Causes of Student Cheating. Res. High Educ. 50, 293–313. doi:10.1007/s11162-008-9116-5

Rogers, C. (2006). Faculty Perceptions about E-Cheating during Online Testing. J. Comput. Sci. Colleges 22, 206–212.

Rosen, W. A., and Carr, M. E. (2013). “An Autonomous Articulating Desktop Robot for Proctoring Remote Online Examinations,” in Paper Presented at the 2013 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (Oklahoma City, OK, USA: IEEE ). doi:10.1109/fie.2013.6685172

Rovai, A. P. (2000). Online and Traditional Assessments: what Is the Difference?. Internet Higher Edu. 3 (3), 141–151. doi:10.1016/S1096-7516(01)00028-8

Rudrapal, D., Das, S., Debbarma, S., Kar, N., and Debbarma, N. (2012). Voice Recognition and Authentication as a Proficient Biometric Tool and its Application in Online Exam for P.H People. Ijca 39, 6–12. doi:10.5120/4870-7297

Schwartz, B. M., Tatum, H. E., and Hageman, M. C. (2013). College Students' Perceptions of and Responses to Cheating at Traditional, Modified, and Non-honor System Institutions. Ethics Behav. 23, 463–476. doi:10.1080/10508422.2013.814538

Şendağ, S., Duran, M., and Robert Fraser, M. (2012). Surveying the Extent of Involvement in Online Academic Dishonesty (E-dishonesty) Related Practices Among university Students and the Rationale Students Provide: One university’s Experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28 (3), 849–860. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.004

Serwatka, J. A. (2003). Assessment in On-Line CIS Courses. J. Comp. Inf. Syst. 44 (1), 16–20. doi:10.1080/08874417.2003.11647547

Shuey, S. (2002). Assessing Online Learning in Higher Education. J. Instruction Deliv. Syst. 16 (2), 13–18.

Smith, A. (2005). “A Comparison of Traditional and Non-traditional Students in the Frequency and Type of Self-Reported Academic Dishonesty,” in Paper Presented at the 25th Annual Great Plains Students’ Psychology Convention (Omaha, NE: IEEE ).

Sterngold, A. (2004). Confronting Plagiarism:How Conventional Teaching Invites Cyber-Cheating. Change Mag. Higher Learn. 36, 16–21. doi:10.1080/00091380409605575

Stuber-McEwen, D., Wiseley, P., and Hoggatt, S. (2009). Point, Click, and Cheat: Frequency and Type of Academic Dishonesty in the Virtual Classroom. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 12 (3), 1.

Stuber-McEwen, D., Wiseley, P., Masters, C., Smith, A., and Mecum, M. (2005). “Faculty Perceptions versus Students’ Self-Reported Frequency of Academic Dishonesty,” in Paper Presented at the 25th Annual Meeting of the Association for Psychological & Educational Research (Kansas, Emporia, K S: IEEE ).

Swauger, S. (2020). Software that Monitors Students during Tests Perpetuates Inequality and Violates Their Privacy . MIT Technical Review. Available at: https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/08/07/1006132/software-algorithms-proctoring-online-tests-ai-ethics/ .

Tatum, H., and Schwartz, B. M. (2017). Honor Codes: Evidence Based Strategies for Improving Academic Integrity. Theor. Into Pract. 56 (2), 129–135. doi:10.1080/00405841.2017.1308175

Tolman, S. (2017). Academic Dishonesty in Online Courses: Considerations for Graduate Preparatory Programs in Higher Education. Coll. Student J. 51, 579–584.

Truong, B. T., and Venkatesh, S. (2007). Video Abstraction. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 3 (1), 3. doi:10.1145/1198302.1198305

Ullah, A., Xiao, H., Lilley, M., and Barker, T. (2012). Using challenge Questions for Student Authentication in Online Examination. Iji 5, 631–639. doi:10.20533/iji.1742.4712.2012.0072

Underwood, J., and Szabo, A. (2003). Academic Offences and E-Learning: Individual Propensities in Cheating. Br. J. Educ. Tech. 34 (4), 467–477. doi:10.1111/1467-8535.00343

Vachris, M. A. (1999). Teaching Principles of Economics without “Chalk and Talk”: The Experience of CNU Online. J. Econ. Edu. 30 (3), 292–303. doi:10.1080/00220489909595993

Varble, D. (2014). Reducing Cheating Opportunities in Online Test. Atlantic Marketing J. 3 (3), 131–149.

Wahid, A., Sengoku, Y., and Mambo, M. (2015). “Toward Constructing A Secure Online Examination System,” in Paper Presented at the Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (Bali, Indonesia: IEEE ). doi:10.1145/2701126.2701203

Warnken, P. (2004). Academic Originalsin: Plagiarism, the Internet, and Librarians. The J. Acad. Librarianship 30 (3), 237–242. doi:10.1016/j.jal.2003.11.011

Watson, G., and Sottile, J. (2010). Cheating in the Digital Age: Do Students Cheat More in Online Courses?. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 13 (1). Available at: http://www.westga.edu/∼distance/ojdla/spring131/watson131.html .

Whitaker, E. E. (1993). A Pedagogy to Address Plagiarism. Coll. Teach. 42, 161–164. doi:10.2307/358386

Zhao, Q., and Ye, M. (2010). “The Application and Implementation of Face Recognition in Authentication System for Distance Education,” in Paper Presented at the 2010 International Conference on Networking and Digital Society (Wenzhou, China: IEEE ).

Keywords: academic integrity, academic dishonesty, cheating, online courses, remote teaching

Citation: Holden OL, Norris ME and Kuhlmeier VA (2021) Academic Integrity in Online Assessment: A Research Review. Front. Educ. 6:639814. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.639814

Received: 09 December 2020; Accepted: 30 June 2021; Published: 14 July 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Holden, Norris and Kuhlmeier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valerie A. Kuhlmeier, [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2021

Academic integrity at doctoral level: the influence of the imposter phenomenon and cultural differences on academic writing

- Jennifer Cutri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5328-5332 1 ,

- Amar Freya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2147-6959 1 ,

- Yeni Karlina ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6989-2516 1 ,

- Sweta Vijaykumar Patel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9363-9262 1 ,

- Mehdi Moharami ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6435-8501 1 ,

- Shaoru Zeng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8884-0968 1 ,

- Elham Manzari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2323-5614 1 &

- Lynette Pretorius ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8998-7686 1

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 17 , Article number: 8 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

21 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

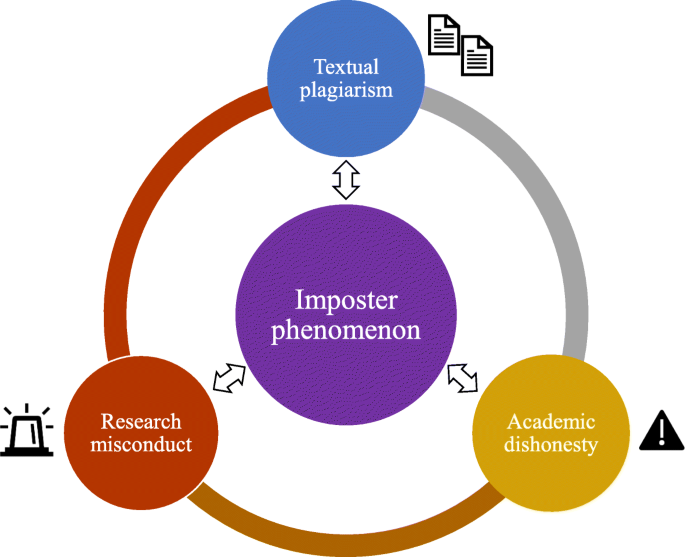

This conceptual review seeks to reframe the view of academic integrity as something to be enforced to an academic skill that needs to be developed. The authors highlight how practices within academia create an environment where feelings of inadequacy thrive, leading to behaviours of unintentional academic misconduct. Importantly, this review includes practical suggestions to help educators and higher education institutions support doctoral students’ academic integrity skills. In particular, the authors highlight the importance of explicit academic integrity instruction, support for the development of academic literacy skills, and changes in supervisory practices that encourage student and supervisor reflexivity. Therefore, this review argues that, through the use of these practical strategies, academia can become a space where a culture of academic integrity can flourish.

Introduction

In the contemporary higher education environment, issues of academic integrity and credibility are turning matters of learning into matters of surveillance and enforcement. Increasingly, higher education institutions are relying on text-matching software (such as Turnitin) and the monitoring or scrutiny of students (e.g., through practices such as online proctoring) as a proxy to measure their level of academic integrity (Dawson 2021 ). Indeed, failure to adhere to these often contextually and socially constructed rules of academic integrity is termed academic misconduct or dishonesty and can lead to severe consequences for students. As Dawson ( 2021 ) notes, this approach is adversarial, focussing on detection rather than encouraging academic integrity. This adversarial approach is also reflected in recent changes to Australian federal legislation (see the Prohibiting Academic Cheating Services Act 2020 ), with provision of an academic cheating service now attracting criminal or civil penalties. There is also increasing concern about the “ threats to academic integrity [ …] due to the wide-spread growth of commercial essay services and attempts by criminal actors to entice students into deceptive or fraudulent activity” (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) 2021 para. 2 emphasis added). Despite this often adversarial language, however, TEQSA also acknowledges that there is a need to promote academic integrity practices by, for example, working with experts to create an Academic Integrity Toolkit (TEQSA 2021 ).

Interestingly, the higher education environment now appears to lead educators to a dichotomous choice to either be “pro-integrity” or “anti-cheating” (Dawson 2021 p. 3). In this conceptual review, we seek to challenge this perception. We focus on how doctoral education programs can foster academic integrity skills development to create an environment where policies and surveillance strategies are incorporated into pedagogical practice. East ( 2009 ) highlights the importance of viewing academic integrity development as a holistic and aligned approach that supports the development of an honest community within the university. Furthermore, Clarence ( 2020 ) argues that doctoral education is underpinned by the axiological belief that graduates should be confident scholars who value integrity in research, authenticity, and ethics. Therefore, it is our argument that it is the responsibility of educators to explicitly teach these skills as part of doctoral education programs in order to encourage a culture of academic integrity among both staff and students (see, for example, Nayak et al. 2015 ; Richards et al. 2016 ). The long-term benefits of such a culture of academic integrity will include greater awareness of academic integrity for both staff and students, the involvement of students in creating and managing their own academic integrity, a reduction in academic integrity breaches, and improved institutional reputations (Richards et al. 2016 ).