The Role of the Qualitative Researcher

In the following, we'll explore how the researcher conducting qualitative research becomes responsible for maintaining the rigor and credibility of various aspects of the research. In a way, this is analogous to the role statistics, validated and reliable instruments, and standardized measures and methods play in quantitative research.

After reviewing this document, you will be able to:

- Compare the role of the qualitative researcher with the role of standardized instruments, measures, and methods in quantitative analysis.

- Monitoring and reducing bias,

- Developing competence in one's methods,

- Collecting the data,

- Analyzing the data, and

- Presenting the findings.

Integrity of the Research is the Issue

Recall from other qualitative courses that qualitative researchers are as concerned about the integrity of their research as quantitative researchers, but they face different challenges. Before examining how the researcher is key to research integrity in qualitative research, let's note some terminology differences between the methodologies. The below provides them at a glance. These are terms related to research integrity:

In Quantitative: designs, validity, reliability, and generalizability (or external validity) are based on the integrity of the design, and of the methods, and instruments used, and only to a lesser extent to the person of the researcher.

In Qualitative: on the other hand, credibility, dependability, and transferability rely on the person and performance of the researcher.

This is why we talk about the role of the researcher in qualitative research.

The Integrity of the Research Equals The Integrity of the Researcher

Of course, this is true of both quantitative and qualitative research. Researchers make errors, and these threaten the validity, reliability, and utility of their studies.

Qualitative researchers, however, lack many of the protections against errors that the statistical methods, standardized measures, and classical designs afford. They must rely on their own competence, openness, and honesty. That is, on their person. Thus, their role, the role of the researcher is more open to scrutiny.

Role of Researcher: Monitoring and Reducing Bias

Bias is a source of error. When a quantitative researcher administers a standardized test, bias is less a problem than when a qualitative researcher has a conversation with a participant. Why?

The researcher's ideas—about the study, her knowledge, about the topic from the literature review, hopes for the study, and simply human distractibility—crop up constantly and can distort what she hears. Confirmation bias—(the name for this) afflicts quantitative researchers, too, but more often when they are analyzing data and seeing what they are disposed to see. Qualitative researchers, whose human brains are trained to find meaning in everything, encounter confirmation bias in every interaction with both participants and data.

Therefore, monitoring and reducing one's disposition to interpret too quickly is an essential part of the researcher's role. Qualitative researchers have evolved a variety of methods for this, such as the famous phenomenological reduction and epoché, but every design within qualitative methodology requires an explicit description of how the researcher will remain conscious of his or her previous knowledge and dispositions and how he or she will control the intrusion of bias.

For example, many qualitative researchers practice mindfulness meditation as a means to become aware when their thoughts are about previous knowledge rather than open and receptive to the information from the participant.

Role of Researcher: Developing Competence in Methods

Many novice researchers think they are competent to do qualitative research. Unfortunately, they are usually wrong.

Qualitative methods, like quantitative methods, require implementing specialized skills correctly. Competence in these skills is required at all these points:

- Explaining the study without biasing the potential participants.

- Conducting interviews properly, according to the design.

- Making appropriate field observations.

- Selecting appropriate artifacts, images, journal portions, and so on.

- Handling data per design.

- Analyzing and interpreting the data per the design.

This competence is not taught in most methods courses; novice researchers are often expected to obtain training and practice on their own. What should they do?

Here are some ideas, although they are not prescriptions and you may find many other ways to develop competence.

The first step: is to self-assess your competence. Assume you do not have competence in each of the skill areas unless you have demonstrated it to someone who knows. If you perform interviews of clients, for example, but have never been taught to do interviews for research, assume you do not have the competence until a researcher who uses interviews tells you that you do.

The next step: is to talk with your mentor— about a plan to get training. For example, many learners who need to demonstrate competence in qualitative interviews do a few practice interviews and ask their mentors to critique their technique. The coaching not only amounts to a kind of training, but the mentor can then attest to the researcher's baseline competence. Another common plan is to attend training workshops in the actual design—such as grounded theory—conducted in research organizations or universities.

For each skill set your design requires you to have, including practicing the analysis methods, create a training plan that includes demonstrating competence to someone.

Is this more work? Maybe so, maybe not. If you were conducting a multiple regression analysis and did not know how to do that, you'd have to learn it, practice it, and demonstrate your competence to someone. So, it's all a matter of perspective.

Role of Researcher: Collecting and Analyzing Data

There are far too many complications in collecting and analyzing qualitative data to cover in this presentation. Have you ever:

- Wired someone with a microphone and inadvertently touched a sensitive body part?

- Sat in a schoolyard to make field observations amid the chaos and swirl of 200 hundred children at recess and known where to start?

- Been confronted with 500 pages of a single-spaced transcript and, known where to start?

- Brought a straying interviewee back to the topic in a way that not only did not offend but actually improved rapport?

- Asked questions that didn't betray what you think the answer should be?

- Sorted through 10,000 sentences or 500 pictures to identify which ones should be retained as data and which ones could be discarded?

- Recognized when you have an actual finding. In other words, can you spot a finding in qualitative analysis?

These are but a few of the challenges that the qualitative researcher faces. Are you ready? Probably not. What should you do?

- Acknowledge that you are a novice. A dissertation is an apprenticeship or internship in research. No one expects the apprentice or intern to be a master.

- Committee members.

- Other dissertators, those in your mentor's courseroom, but also others around the world. Read similar dissertations and write to their authors asking for tips and tricks. Authors love knowing that someone is reading their work.

- Professional researchers. These professionals are scholars, and they will help, at least many of them will. Two or three e-mails that yield excellent advice—and perhaps an ongoing relationship—are well worth the investment of anxiety and time.

Role of Researcher: Presenting the Findings

Most of us present findings in writing. While a few will also present their findings in posters and oral presentations, everyone in Track 3 will at least present them in writing.

Develop and demonstrate competence in writing!

Dr. James Meredith of the Capella Writing Program points out that you have to write your way out of the doctoral program.

Capella makes an extraordinary effort to provide support and instruction in scholarly writing, primarily through the Capella Writing Program and the Online Writing Center. Failing to take advantage of all these resources will result in your findings being sent back to you for revision. Why waste the time? Right now, you can and should start to make use of:

- The Scholarly Communications Guide; it's available in the Dissertation Research Seminar courseroom for you.

- Review and get familiar with the Dissertation Chapter Four Guide (qualitative or quantitative); this too is available in the Dissertation Milestone Resources area on iGuide. It offers a conventional way to structure the findings chapter of the dissertation. By learning it now, you'll have in mind a set of ideas about what sort of competence in writing and in analyzing your data you'll need at this point in the project.

- Resources for writing in the Capella Writing Program; these are broad and deep—you will be ignoring a treasure that would help you succeed if you fail to take advantage of these.

- And, perhaps most important, read dissertations and articles; read dozens in your specific methodology and design (for example, phenomenology or grounded theory). Get to know what other novice researchers are doing and how well they are doing it. Open your mind to learning from them, and remain critical of their errors and foibles: we all have them. Make it your goal to absorb the style and conventions of writers using your methodology and design.

- Learn APA style; again, Dr. Meredith reminds us that the correct use of APA format and style is an automatic claim to credibility! Remember that the converse is also true: APA errors, or even ignoring the format and style rules, automatically deprive your writing of credibility and trustworthiness.

We've covered the importance of evaluating your own role as the researcher, in the various elements of a qualitative study:

- Monitoring and reducing bias.

- Developing competence in one's methods.

- Collecting the data.

- Analyzing the data.

Doc. reference: phd_t3_u06s1_qualrole.html

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

- Current Students Hub

Doctoral handbook

You are here

- Dissertation Content

A doctoral dissertation makes an original contribution to knowledge, as defined in a discipline or an interdisciplinary domain and addresses a significant researchable problem. Not all problems are researchable and not all are significant. Problems that can be solved by a mere descriptive exercise are not appropriate for the PhD dissertation. Acceptable problems are those that:

- pose a puzzle to the field at a theoretical, methodological, or policy level;

- make analytical demands for solution, rather than mere cataloging or descriptive demands; and

- can yield to a reasonable research methodology.

The doctoral dissertation advisor, reading committee, and oral exam committee provide further guidance and details with regard to dissertation content and format. General formatting and submission guidelines are published by the University Registrar. The American Psychological Association (APA) publication guidelines normally apply to GSE doctoral dissertations, but is not required if the advisor and relevant committees determine that an alternative, and academically acceptable, protocol is more appropriate.

Published Papers and Multiple Authorship

The inclusion of published papers in a dissertation is the prerogative of the major department. Where published papers or ready-for-publication papers are included, the following criteria must be met:

1. There must be an introductory chapter that integrates the general theme of the research and the relationship between the chapters. The introduction may also include a review of the literature relevant to the dissertation topic that does not appear in the chapters.

2. Multiple authorship of a published paper should be addressed by clearly designating, in an introduction, the role that the dissertation author had in the research and production of the published paper. The student must have a major contribution to the research and writing of papers included in the dissertation.

3. There must be adequate referencing of where individual papers have been published.

4. Written permission must be obtained for all copyrighted materials; letters of permission must be uploaded electronically in PDF form when submitting the dissertation. Please see the following website for more information on the use of copyrighted materials: http://library.stanford.edu/using/copyright-reminder .

5. The submitted material must be in a form that is legible and reproducible as required by these specifications. The Office of the University Registrar will approve a dissertation if there are no deviations from the normal specifications that would prevent proper dissemination and utilization of the dissertation. If the published material does not correspond to these standards, it will be necessary for the student to reformat that portion of the dissertation.

6. Multiple authorship has implications with respect to copyright and public release of the material. Be sure to discuss copyright clearance and embargo options with your co-authors and your advisor well in advance of preparing your thesis for submission.

- Printer-friendly version

Handbook Contents

- Timetable for the Doctoral Degree

- Degree Requirements

- Registration or Enrollment for Milestone Completion

- The Graduate Study Program

- Student Virtual and Teleconference Participation in Hearings

- First Year (3rd Quarter) Review

- Second Year (6th Quarter) Review

- Committee Composition for First- and Second-Year Reviews

- Advancement to Candidacy

- Academic Program Revision

- Dissertation Proposal

- Dissertation Reading Committee

- University Oral Examination

- Submitting the Dissertation

- Registration and Student Statuses

- Graduate Financial Support

- GSE Courses

- Curriculum Studies and Teacher Education (CTE)

- Developmental and Psychological Sciences (DAPS)

- Learning Sciences and Technology Design (LSTD)

- Race, Inequality, and Language in Education (RILE)

- Social Sciences, Humanities, and Interdisciplinary Policy Studies in Education (SHIPS)

- Contact Information

- Stanford University Honor Code

- Stanford University Fundamental Standard

- Doctoral Programs Degree Progress Checklist

- GSE Open Access Policies

PhD students, please contact

MA POLS and MA/PP students, please contact

EDS, ICE/IEPA, Individually Designed, LDT, MA/JD, MA/MBA students, please contact

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

How to tackle the PhD dissertation

Finding time to write can be a challenge for graduate students who often juggle multiple roles and responsibilities. Mabel Ho provides some tips to make the process less daunting

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Analytical testing is the key to industry collaborations

Is it time to turn off turnitin, use ai to get your students thinking critically, taming anxiety around public speaking, emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn.

Writing helps you share your work with the wider community. Your scholarship is important and you are making a valuable contribution to the field. While it might be intimidating to face a blank screen, remember, your first draft is not your final draft! The difficult part is getting something on the page to begin with.

As the adage goes, a good dissertation is a done dissertation, and the goal is for you to find balance in your writing and establish the steps you can take to make the process smoother. Here are some practical strategies for tackling the PhD dissertation.

Write daily

This is a time to have honest conversations with yourself about your writing and work habits. Do you tackle the most challenging work in the morning? Or do you usually start with emails? Knowing your work routine will help you set parameters for the writing process, which includes various elements, from brainstorming ideas to setting outlines and editing. Once you are aware of your energy and focus levels, you’ll be ready to dedicate those times to writing.

While it might be tempting to block a substantial chunk of time to write and assume anything shorter is not useful, that is not the case. Writing daily, whether it’s a paragraph or several pages, keeps you in conversation with your writing practice. If you schedule two hours to write, remember to take a break during that time and reset. You can try:

- The Pomodoro Technique: a time management technique that breaks down your work into intervals

- Taking breaks: go outside for a walk or have a snack so you can come back to your writing rejuvenated

- Focus apps: it is easy to get distracted by devices and lose direction. Here are some app suggestions: Focus Bear (no free version); Forest (free version available); Cold Turkey website blocker (free version available) and Serene (no free version).

This is a valuable opportunity to hone your time management and task prioritisation skills. Find out what works for you and put systems in place to support your practice.

- Resources on academic writing for higher education professionals

- Stretch your work further by ‘triple writing’

- What is your academic writing temperament?

Create a community

While writing can be an isolating endeavour, there are ways to start forming a community (in-person or virtual) to help you set goals and stay accountable. There might be someone in your cohort who is also at the writing stage with whom you can set up a weekly check-in. Alternatively, explore your university’s resources and centres because there may be units and departments on campus that offer helpful opportunities, such as a writing week or retreat. Taking advantage of these opportunities helps combat isolation, foster accountability and grow networks. They can even lead to collaborations further down the line.

- Check in with your advisers and mentors. Reach out to your networks to find out about other people’s writing processes and additional resources.

- Don’t be afraid to share your work. Writing requires constant revisions and edits and finding people who you trust with feedback will help you grow as a writer. Plus, you can also read their work and help them with their editing process.

- Your community does not have to be just about writing! If you enjoy going on hikes or trying new coffee shops, make that part of your weekly habit. Sharing your work in different environments will help clarify your thoughts and ideas.

Address the why

The PhD dissertation writing process is often lengthy and it is sometimes easy to forget why you started. In these moments, it can be helpful to think back to what got you excited about your research and scholarship in the first place. Remember it is not just the work but also the people who propelled you forward. One idea is to start writing your “acknowledgements” section. Here are questions to get you started:

- Do you want to dedicate your work to someone?

- What ideas sparked your interest in this journey?

- Who cheered you on?

This practice can help build momentum, as well as serve as a good reminder to carve out time to spend with your community.

You got this!

Writing is a process. Give yourself grace, as you might not feel motivated all the time. Be consistent in your approach and reward yourself along the way. There is no single strategy when it comes to writing or maintaining motivation, so experiment and find out what works for you.

Suggested readings

- Thriving as a Graduate Writer by Rachel Cayley (2023)

- Destination Dissertation by Sonja K. Foss and William Waters (2015)

- The PhD Writing Handbook by Desmond Thomas (2016).

Mabel Ho is director of professional development and student engagement at Dalhousie University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

Analytical testing is the key to industry collaborations

A framework to teach library research skills, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools, chatgpt’s impact on nursing education and assessments.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

- Privacy Policy

Home » Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Table of Contents

Dissertation

Definition:

Dissertation is a lengthy and detailed academic document that presents the results of original research on a specific topic or question. It is usually required as a final project for a doctoral degree or a master’s degree.

Dissertation Meaning in Research

In Research , a dissertation refers to a substantial research project that students undertake in order to obtain an advanced degree such as a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree.

Dissertation typically involves the exploration of a particular research question or topic in-depth, and it requires students to conduct original research, analyze data, and present their findings in a scholarly manner. It is often the culmination of years of study and represents a significant contribution to the academic field.

Types of Dissertation

Types of Dissertation are as follows:

Empirical Dissertation

An empirical dissertation is a research study that uses primary data collected through surveys, experiments, or observations. It typically follows a quantitative research approach and uses statistical methods to analyze the data.

Non-Empirical Dissertation

A non-empirical dissertation is based on secondary sources, such as books, articles, and online resources. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as content analysis or discourse analysis.

Narrative Dissertation

A narrative dissertation is a personal account of the researcher’s experience or journey. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnography.

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as meta-analysis or thematic analysis.

Case Study Dissertation

A case study dissertation is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or organization. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, observations, or document analysis.

Mixed-Methods Dissertation

A mixed-methods dissertation combines both quantitative and qualitative research approaches to gather and analyze data. It typically uses methods such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as statistical analysis.

How to Write a Dissertation

Here are some general steps to help guide you through the process of writing a dissertation:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that you are passionate about and that is relevant to your field of study. It should be specific enough to allow for in-depth research but broad enough to be interesting and engaging.

- Conduct research : Conduct thorough research on your chosen topic, utilizing a variety of sources, including books, academic journals, and online databases. Take detailed notes and organize your information in a way that makes sense to you.

- Create an outline : Develop an outline that will serve as a roadmap for your dissertation. The outline should include the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Write the introduction: The introduction should provide a brief overview of your topic, the research questions, and the significance of the study. It should also include a clear thesis statement that states your main argument.

- Write the literature review: The literature review should provide a comprehensive analysis of existing research on your topic. It should identify gaps in the research and explain how your study will fill those gaps.

- Write the methodology: The methodology section should explain the research methods you used to collect and analyze data. It should also include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses in your approach.

- Write the results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables to help illustrate your data.

- Write the discussion: The discussion section should interpret your results and explain their significance. It should also address any limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research.

- Write the conclusion: The conclusion should summarize your main findings and restate your thesis statement. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

- Edit and revise: Once you have completed a draft of your dissertation, review it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and free of errors. Make any necessary revisions and edits before submitting it to your advisor for review.

Dissertation Format

The format of a dissertation may vary depending on the institution and field of study, but generally, it follows a similar structure:

- Title Page: This includes the title of the dissertation, the author’s name, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methods, and findings.

- Table of Contents: A list of the main sections and subsections of the dissertation, along with their page numbers.

- Introduction : A statement of the problem or research question, a brief overview of the literature, and an explanation of the significance of the study.

- Literature Review : A comprehensive review of the literature relevant to the research question or problem.

- Methodology : A description of the methods used to conduct the research, including data collection and analysis procedures.

- Results : A presentation of the findings of the research, including tables, charts, and graphs.

- Discussion : A discussion of the implications of the findings, their significance in the context of the literature, and limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : A summary of the main points of the study and their implications for future research.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the dissertation.

- Appendices : Additional materials that support the research, such as data tables, charts, or transcripts.

Dissertation Outline

Dissertation Outline is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of dissertation

- Author name

- Institutional affiliation

- Date of submission

- Brief summary of the dissertation’s research problem, objectives, methods, findings, and implications

- Usually around 250-300 words

Table of Contents:

- List of chapters and sections in the dissertation, with page numbers for each

I. Introduction

- Background and context of the research

- Research problem and objectives

- Significance of the research

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing literature on the research topic

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Theoretical framework and concepts

III. Methodology

- Research design and methods used

- Data collection and analysis techniques

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation and analysis of data collected

- Findings and outcomes of the research

- Interpretation of the results

V. Discussion

- Discussion of the results in relation to the research problem and objectives

- Evaluation of the research outcomes and implications

- Suggestions for future research

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of the research findings and outcomes

- Implications for the research topic and field

- Limitations and recommendations for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the dissertation

VIII. Appendices

- Additional materials that support the research, such as tables, figures, or questionnaires.

Example of Dissertation

Here is an example Dissertation for students:

Title : Exploring the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Achievement and Well-being among College Students

This dissertation aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on the academic achievement and well-being of college students. Mindfulness meditation has gained popularity as a technique for reducing stress and enhancing mental health, but its effects on academic performance have not been extensively studied. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the study will compare the academic performance and well-being of college students who practice mindfulness meditation with those who do not. The study will also examine the moderating role of personality traits and demographic factors on the effects of mindfulness meditation.

Chapter Outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Background and rationale for the study

- Research questions and objectives

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the dissertation structure

Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Definition and conceptualization of mindfulness meditation

- Theoretical framework of mindfulness meditation

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and academic achievement

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and well-being

- The role of personality and demographic factors in the effects of mindfulness meditation

Chapter 3: Methodology

- Research design and hypothesis

- Participants and sampling method

- Intervention and procedure

- Measures and instruments

- Data analysis method

Chapter 4: Results

- Descriptive statistics and data screening

- Analysis of main effects

- Analysis of moderating effects

- Post-hoc analyses and sensitivity tests

Chapter 5: Discussion

- Summary of findings

- Implications for theory and practice

- Limitations and directions for future research

- Conclusion and contribution to the literature

Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Recap of the research questions and objectives

- Summary of the key findings

- Contribution to the literature and practice

- Implications for policy and practice

- Final thoughts and recommendations.

References :

List of all the sources cited in the dissertation

Appendices :

Additional materials such as the survey questionnaire, interview guide, and consent forms.

Note : This is just an example and the structure of a dissertation may vary depending on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the institution or the supervisor.

How Long is a Dissertation

The length of a dissertation can vary depending on the field of study, the level of degree being pursued, and the specific requirements of the institution. Generally, a dissertation for a doctoral degree can range from 80,000 to 100,000 words, while a dissertation for a master’s degree may be shorter, typically ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 words. However, it is important to note that these are general guidelines and the actual length of a dissertation can vary widely depending on the specific requirements of the program and the research topic being studied. It is always best to consult with your academic advisor or the guidelines provided by your institution for more specific information on dissertation length.

Applications of Dissertation

Here are some applications of a dissertation:

- Advancing the Field: Dissertations often include new research or a new perspective on existing research, which can help to advance the field. The results of a dissertation can be used by other researchers to build upon or challenge existing knowledge, leading to further advancements in the field.

- Career Advancement: Completing a dissertation demonstrates a high level of expertise in a particular field, which can lead to career advancement opportunities. For example, having a PhD can open doors to higher-paying jobs in academia, research institutions, or the private sector.

- Publishing Opportunities: Dissertations can be published as books or journal articles, which can help to increase the visibility and credibility of the author’s research.

- Personal Growth: The process of writing a dissertation involves a significant amount of research, analysis, and critical thinking. This can help students to develop important skills, such as time management, problem-solving, and communication, which can be valuable in both their personal and professional lives.

- Policy Implications: The findings of a dissertation can have policy implications, particularly in fields such as public health, education, and social sciences. Policymakers can use the research to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for the population.

When to Write a Dissertation

Here are some situations where writing a dissertation may be necessary:

- Pursuing a Doctoral Degree: Writing a dissertation is usually a requirement for earning a doctoral degree, so if you are interested in pursuing a doctorate, you will likely need to write a dissertation.

- Conducting Original Research : Dissertations require students to conduct original research on a specific topic. If you are interested in conducting original research on a topic, writing a dissertation may be the best way to do so.

- Advancing Your Career: Some professions, such as academia and research, may require individuals to have a doctoral degree. Writing a dissertation can help you advance your career by demonstrating your expertise in a particular area.

- Contributing to Knowledge: Dissertations are often based on original research that can contribute to the knowledge base of a field. If you are passionate about advancing knowledge in a particular area, writing a dissertation can help you achieve that goal.

- Meeting Academic Requirements : If you are a graduate student, writing a dissertation may be a requirement for completing your program. Be sure to check with your academic advisor to determine if this is the case for you.

Purpose of Dissertation

some common purposes of a dissertation include:

- To contribute to the knowledge in a particular field : A dissertation is often the culmination of years of research and study, and it should make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate mastery of a subject: A dissertation requires extensive research, analysis, and writing, and completing one demonstrates a student’s mastery of their subject area.

- To develop critical thinking and research skills : A dissertation requires students to think critically about their research question, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on evidence. These skills are valuable not only in academia but also in many professional fields.

- To demonstrate academic integrity: A dissertation must be conducted and written in accordance with rigorous academic standards, including ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting the privacy of participants, and avoiding plagiarism.

- To prepare for an academic career: Completing a dissertation is often a requirement for obtaining a PhD and pursuing a career in academia. It can demonstrate to potential employers that the student has the necessary skills and experience to conduct original research and make meaningful contributions to their field.

- To develop writing and communication skills: A dissertation requires a significant amount of writing and communication skills to convey complex ideas and research findings in a clear and concise manner. This skill set can be valuable in various professional fields.

- To demonstrate independence and initiative: A dissertation requires students to work independently and take initiative in developing their research question, designing their study, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This demonstrates to potential employers or academic institutions that the student is capable of independent research and taking initiative in their work.

- To contribute to policy or practice: Some dissertations may have a practical application, such as informing policy decisions or improving practices in a particular field. These dissertations can have a significant impact on society, and their findings may be used to improve the lives of individuals or communities.

- To pursue personal interests: Some students may choose to pursue a dissertation topic that aligns with their personal interests or passions, providing them with the opportunity to delve deeper into a topic that they find personally meaningful.

Advantage of Dissertation

Some advantages of writing a dissertation include:

- Developing research and analytical skills: The process of writing a dissertation involves conducting extensive research, analyzing data, and presenting findings in a clear and coherent manner. This process can help students develop important research and analytical skills that can be useful in their future careers.

- Demonstrating expertise in a subject: Writing a dissertation allows students to demonstrate their expertise in a particular subject area. It can help establish their credibility as a knowledgeable and competent professional in their field.

- Contributing to the academic community: A well-written dissertation can contribute new knowledge to the academic community and potentially inform future research in the field.

- Improving writing and communication skills : Writing a dissertation requires students to write and present their research in a clear and concise manner. This can help improve their writing and communication skills, which are essential for success in many professions.

- Increasing job opportunities: Completing a dissertation can increase job opportunities in certain fields, particularly in academia and research-based positions.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

This question is about what a researcher does and researcher .

What is the role of a researcher?

The role of a researcher is to use the scientific method and research process to better understand the world around us. Researchers typically work for academic institutions or businesses. Researchers gather data during the project life cycle, analyze the data, and publish the findings to aid new research, enrich scholarly literature, and improve decision-making.

Researcher Duties and Responsibilities:

Work with a team of other researchers and committees to plan research objectives and test parameters

Identify research methods, variables, data collection techniques, and analysis methods

Monitor the project to make sure it follows the requirements and standards

Interpret the data, produce reports discussing research findings and provide recommendations at the end of the project

Determine areas of research to increase knowledge in a particular field

Identify sources of funding, prepare research proposals and submit funding applications

Plan and perform experiments and surveys

Collect, record, and analyze data

Interpret data analysis results and draw inferences and conclusions

Present research results to the committee

Use research results to write reports, papers, and reviews and present findings in journals and conferences

Collaborate with research teams, industry stakeholders, and government agencies

Search for researcher jobs

Related topics, related questions for researcher, recent job searches.

- Registered nurse jobs Resume Location

- Truck driver jobs Resume Location

- Call center representative jobs Resume Location

- Customer service representative jobs Resume

- Delivery driver jobs Resume Location

- Warehouse worker jobs Resume Location

- Account executive jobs Resume Location

- Sales associate jobs Resume Location

- Licensed practical nurse jobs Resume Location

- Company driver jobs Resume

Researcher Jobs

Learn more about researcher jobs.

What qualifications do you need to be a researcher?

What percentage of Researchers are female?

Can a researcher make 100k?

What is a good starting salary for a Researcher?

What skills should I put on my resume for research?

How do I write a research resume?

- Zippia Answers

- Life, Physical, and Social Science

- What Is The Role Of A Researcher

The academic researcher role: enhancing expectations and improved performance

- Published: 01 August 2012

- Volume 65 , pages 525–538, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Svein Kyvik 1

3355 Accesses

67 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article distinguishes between six tasks related to the academic researcher role: (1) networking; (2) collaboration; (3) managing research; (4) doing research; (5) publishing research; and (6) evaluation of research. Data drawn from surveys of academic staff, conducted in Norwegian universities over three decades, provide evidence that the researcher role has become more demanding with respect to all sub-roles, and that academic staff have responded to increasing external and internal demands by enhancing their role performance.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The four-day work week: a chronological, systematic review of the academic literature

Association between social media use and students’ academic performance through family bonding and collective learning: The moderating role of mental well-being

Limited by our limitations

Aksnes, D. W., Frølich, N., & Slipersæter, S. (2010). Science policy and the driving forces behind the internationalization of science: The case of Norway. Science and Public Policy, 35 , 445–457.

Article Google Scholar

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic tribes and territories . Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Bentley, P., & Kyvik, S. (2011). Academic staff and public communication: A survey of popular science publishing across 13 countries. Public Understanding of Science, 20 , 48–63.

Blaxter, L., Hughes, C., & Tight, M. (1998). Writing on academic careers. Studies in Higher Education, 23 , 281–295.

Bok, D. (2003). Universities in the marketplace. The commercialization of higher education . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Calvert, J. (2000). Is there a role for basic research in Mode 2? Vest, 13 , 35–51.

Cooper, M. H. (2009). Commercialization of the university and problem choice by academic biological scientists. Science, Technology and Human Values, 34 , 629–653.

Dunwoody, S. (1986). The scientist as source. In S. Friedman, S. Dunwoody, & C. L. Rogers (Eds.), Scientists and journalists. Reporting science as news (pp. 3–16). New York: The Free Press.

Enders, J. (2001) (Ed.). Academic staff in Europe. Changing Contexts and Conditions . Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Etzkowitz, H. (1992). Individual investigators and their research groups. Minerva, 30 , 28–50.

Gornitzka, Å., & Langfeldt, L. (Eds.). (2008). Borderless knowledge. Understanding the “New” internationalisation of research and higher education in Norway . Dordrecht: Springer.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Kyvik, S. (2010). Are the concepts basic research, applied research and experimental development still useful? An empirical investigation among Norwegian academics. Science and Public Policy, 37 , 343–353.

Hage, J., & Powers, C. H. (1992). Post-industrial lives. Roles and relationships in the 21st century . Newbury Park: SAGE Publications.

Henkel, M. (2000). Academic identities and policy change in higher education . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Katz, J. S., & Martin, B. R. (1997). What is research collaboration? Research Policy, 26 , 1–18.

Kyvik, S. (2003). Changing trends in publishing behaviour among university faculty, 1980–2000. Scientometrics, 58 , 35–48.

Kyvik, S. (2005). Popular science publishing and contributions to public discourse among university faculty. Science Communication, 26 , 288–311.

Kyvik, S. (2007). Changes in funding university research. Consequences for problem choice and research output of academic staff. In J. Enders & B. Jongbloed (Eds.), Public-private dynamics in higher education: Expectations, developments and outcomes (pp. 387–411). Bielefeldt: Transcript Verlag.

Kyvik, S. (2012). Academic salaries in Norway: Increasing emphasis on research achievement. In P. Altbach, L. Reisberg, M. Yudkevich, G. Androushchak, & I. Pacheco (Eds.), Paying the professoriate. A global comparison of compensation and contracts (pp. 255–264). New York: Routledge.

Kyvik, S., & Olsen, T. B. (2008). Does the aging of tenured academic staff affect the research performance of universities? Scientometrics, 76 , 439–455.

Kyvik, S., & Smeby, J. S. (1994). Teaching and research. The relationship between the supervision of graduate students and faculty research performance. Higher Education, 28 , 227–239.

Langfeldt, L., & Kyvik, S. (2011). Researchers as evaluators: Tasks, tensions and politics. Higher Education, 62 , 199–212.

Melin, G. (2000). Pragmatism and self-organization. Research collaboration on the individual level. Research Policy, 29 , 31–40.

Merton, R. (1968). Social theory and social structure . New York: The Free Press.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2001). Re-thinking science: Knowledge and the public in an age of uncertainty . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2003). ‘Mode 2’ revisited: The new production of knowledge. Minerva, 41 , 179–194.

Olsen, T. B., Kyvik, S., & Hovdhaugen, E. (2005). The promotion to full professor—Through competition or by individual competence? Tertiary Education and Management, 11 , 299–316.

Schuster, J. H., & Finkelstein, M. J. (2006). The American faculty. The restructuring of academic work and careers . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sivertsen, G. (2010). A performance indicator based on complete data for the scientific publication output at research institutions. ISSI Newsletter, 6 , 22–28.

Smeby, J. C., & Trondal, J. (2005). Globalisation or europeanisation? International contact among university staff. Higher Education, 49 , 449–466.

Stokes, D. E. (1997). Pasteur’s quadrant. Basic science and technological innovation . Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Ylijoki, O. H., Lyytinen, A., & Marttila, L. (2011). Different research markets: A disciplinary perspective. Higher Education, 62 , 721–740.

Zuckerman, H., & Merton, R. K. (1972). Age, aging, and age structure in science. In M. W. Riley, M. Johnson, & A. Foner (Eds.), Aging and society—Volume three: A sociology of age stratification . New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

NIFU (Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education), Wergelandsveien 7, 0167, Oslo, Norway

Svein Kyvik

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Svein Kyvik .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kyvik, S. The academic researcher role: enhancing expectations and improved performance. High Educ 65 , 525–538 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9561-0

Download citation

Published : 01 August 2012

Issue Date : April 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9561-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Researcher role

- Academic research

- University research

- Academic work

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2024

Measurement and analysis of change in research scholars’ knowledge and attitudes toward statistics after PhD coursework

- Mariyamma Philip 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 512 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

102 Accesses

Metrics details

Knowledge of statistics is highly important for research scholars, as they are expected to submit a thesis based on original research as part of a PhD program. As statistics play a major role in the analysis and interpretation of scientific data, intensive training at the beginning of a PhD programme is essential. PhD coursework is mandatory in universities and higher education institutes in India. This study aimed to compare the scores of knowledge in statistics and attitudes towards statistics among the research scholars of an institute of medical higher education in South India at different time points of their PhD (i.e., before, soon after and 2–3 years after the coursework) to determine whether intensive training programs such as PhD coursework can change their knowledge or attitudes toward statistics.

One hundred and thirty research scholars who had completed PhD coursework in the last three years were invited by e-mail to be part of the study. Knowledge and attitudes toward statistics before and soon after the coursework were already assessed as part of the coursework module. Knowledge and attitudes towards statistics 2–3 years after the coursework were assessed using Google forms. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was also sought.

Knowledge and attitude scores improved significantly subsequent to the coursework (i.e., soon after, percentage of change: 77%, 43% respectively). However, there was significant reduction in knowledge and attitude scores 2–3 years after coursework compared to the scores soon after coursework; knowledge and attitude scores have decreased by 10%, 37% respectively.

The study concluded that the coursework program was beneficial for improving research scholars’ knowledge and attitudes toward statistics. A refresher program 2–3 years after the coursework would greatly benefit the research scholars. Statistics educators must be empathetic to understanding scholars’ anxiety and attitudes toward statistics and its influence on learning outcomes.

Peer Review reports

A PhD degree is a research degree, and research scholars submit a thesis based on original research in their chosen field. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degrees are awarded in a wide range of academic disciplines, and the PhD students are usually referred as research scholars. A comprehensive understanding of statistics allows research scholars to add rigour to their research. This approach helps them evaluate the current practices and draw informed conclusions from studies that were undertaken to generate their own hypotheses and to design, analyse and interpret complex clinical decisions. Therefore, intensive training at the beginning of the PhD journey is essential, as intensive training in research methodology and statistics in the early stages of research helps scholars design and plan their studies efficiently.

The University Grants Commission of India has taken various initiatives to introduce academic reforms to higher education institutions in India and mandated in 2009 that coursework be treated as a prerequisite for PhD preparation and that a minimum of four credits be assigned to one or more courses on research methodology, which could cover areas such as quantitative methods, computer applications, and research ethics. UGC also clearly states that all candidates admitted to PhD programmes shall be required to complete the prescribed coursework during the initial two semesters [ 1 ]. National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) at Bangalore, a tertiary care hospital and medical higher education institute in South India, that trains students in higher education in clinical fields, also introduced coursework in the PhD program for research scholars from various backgrounds, such as basic, behavioral and neurosciences, as per the UGC mandate. Research scholars undertake coursework programs soon after admission, which consist of several modules that include research methodology and statistical software training, among others.

Most scholars approach a course in statistics with the prejudice that statistics is uninteresting, demanding, complex or involve much mathematics and, most importantly, it is not relevant to their career goals. They approach statistics with considerable apprehension and negative attitudes, probably because of their inability to grasp the relevance of the application of the methods in their fields of study. This could be resolved by providing sufficient and relevant examples of the application of statistical techniques from various fields of medical research and by providing hands-on experience to learn how these techniques are applied and interpreted on real data. Hence, research methodology and statistical methods and the application of statistical methods using software have been given much importance and are taught as two modules, named Research Methodology and Statistics and Statistical Software Training, at this institute of medical higher education that trains research scholars in fields as diverse as basic, behavioural and neurosciences. Approximately 50% of the coursework curriculum focused on these two modules. Research scholars were thus given an opportunity to understand the theoretical aspects of the research methodology and statistical methods. They were also given hands-on training on statistical software to analyse the data using these methods and to interpret the findings. The coursework program was designed in this specific manner, as this intensive training would enable the research scholars to design their research studies more effectively and analyse their data in a better manner.

It is important to study attitudes toward statistics because attitudes are known to impact the learning process. Also, most importantly, these scholars are expected to utilize the skills in statistics and research methods to design research projects or guide postgraduate students and research scholars in the near future. Several authors have assessed attitudes toward statistics among various students and examined how attitudes affect academic achievement, how attitudes are correlated with knowledge in statistics and how attitudes change after a training program. There are studies on attitudes toward statistics among graduate [ 2 , 3 , 4 ] and postgraduate [ 5 ] medical students, politics, sociology, ( 6 – 7 ) psychology [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], social work [ 11 ], and management students [ 12 ]. However, there is a dearth of related literature on research scholars, and there are only two studies on the attitudes of research scholars. In their study of doctoral students in education-related fields, Cook & Catanzaro (2022) investigated the factors that contribute to statistics anxiety and attitudes toward statistics and how anxiety, attitudes and plans for future research use are connected among doctoral students [ 13 ]. Another study by Sohrabi et al. (2018) on research scholars assessed the change in knowledge and attitude towards teaching and educational design of basic science PhD students at a Medical University after a two-day workshop on empowerment and familiarity with the teaching and learning principles [ 14 ]. There were no studies that assessed changes in the attitudes or knowledge of research scholars across the PhD training period or after intensive training programmes such as PhD coursework. Even though PhD coursework has been established in institutes of higher education in India for more than a decade, there are no published research on the effectiveness of coursework from Indian universities or institutes of higher education.

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of PhD coursework and whether intensive training programs such as PhD coursework can influence the knowledge and attitudes toward statistics of research scholars. Additionally, it would be interesting to know if the acquired knowledge could be retained longer, especially 2–3 years after the coursework, the crucial time of PhD data analysis. Hence, this study compares the scores of knowledge in statistics and attitude toward statistics of the research scholars at different time points of their PhD training, i.e., before, soon after and 2–3 years after the coursework.

Participants

This is an observational study of single group with repeated assessments. The institute offers a three-month coursework program consisting of seven modules, the first module is ethics; the fifth is research methodology and statistics; and the last is neurosciences. The study was conducted in January 2020. All research scholars of the institute who had completed PhD coursework in the last three years were considered for this study ( n = 130). Knowledge and attitudes toward statistics before and soon after the coursework module were assessed as part of the coursework program. They were collected on the first and last day of the program respectively. The author who was also the coordinator of the research methodology and statistics module of the coursework have obtained the necessary permission to use the data for this study. The scholars invited to be part of the study by e-mail. Knowledge and attitude towards statistics 2–3 years after the coursework were assessed online using Google forms. They were also administered a semi structured questionnaire to elicit details about the usefulness of coursework. Participation was voluntary, and consent was also sought online. The confidentiality of the data was assured. Data were not collected from research scholars of Biostatistics or from research scholars who had more than a decade of experience or who had been working in the institute as faculty, assuming that their scores could be higher and could bias the findings. This non funded study was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Instruments

Knowledge in Statistics was assessed by a questionnaire prepared by the author and was used as part of the coursework evaluation. The survey included 25 questions that assessed the knowledge of statistics on areas such as descriptive statistics, sampling methods, study design, parametric and nonparametric tests and multivariate analyses. Right answers were assigned a score of 1, and wrong answers were assigned a score of 0. Total scores ranged from 0 to 25. Statistics attitudes were assessed by the Survey of Attitudes toward Statistics (SATS) scale. The SATS is a 36-item scale that measures 6 domains of attitudes towards statistics. The possible range of scores for each item is between 1 and 7. The total score was calculated by dividing the summed score by the number of items. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes. The SAT-36 is a copyrighted scale, and researchers are allowed to use it only with prior permission. ( 15 – 16 ) The author obtained permission for use in the coursework evaluation and this study. A semi structured questionnaire was also used to elicit details about the usefulness of coursework.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, number and percentages were used to describe the socio-demographic data. General Linear Model Repeated Measures of Analysis of variance was used to compare knowledge and attitude scores across assessments. Categorical data from the semi structured questionnaire are presented as percentages. All the statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p value < 0.05 was set a priori as the threshold for statistical significance. IBM SPSS (28.0) was used to analyse the data.

One hundred and thirty research scholars who had completed coursework (CW) in the last 2–3 years were considered for the study. These scholars were sent Google forms to assess their knowledge and attitudes 2–3 years after coursework. 81 scholars responded (62%), and 4 scholars did not consent to participate in the study. The data of 77 scholars were merged with the data obtained during the coursework program (before and soon after CW). Socio-demographic characteristics of the scholars are presented in Table 1 .

The age of the respondents ranged from 23 to 36 years, with an average of 28.7 years (3.01), and the majority of the respondents were females (65%). Years of experience (i.e., after masters) before joining a PhD programme ranged from 0.5 to 9 years, and half of them had less than three years of experience before joining the PhD programme (median-3). More than half of those who responded were research scholars from the behavioural sciences (55%), while approximately 30% were from the basic sciences (29%).

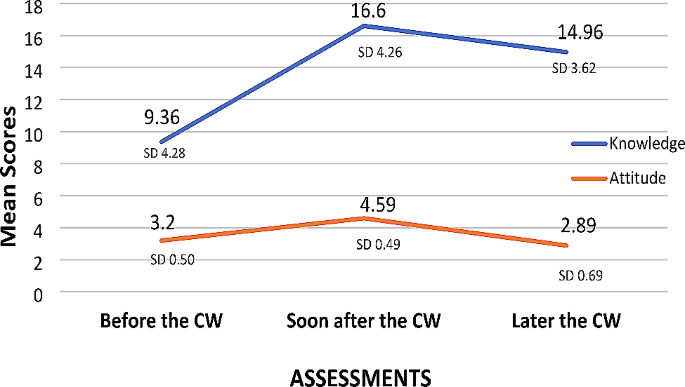

General Linear Model Repeated Measures of Analysis of variance was used to compare the knowledge and attitude scores of scholars before, soon after and 2–3 after the coursework (will now be referred as “later the CW”), and the results are presented below (Table 2 ; Fig. 1 ).

Comparison of knowledge and attitude scores across the assessments. Later the CW – 2–3 years after the coursework

The scores for knowledge and attitude differed significantly across time. Scores of knowledge and attitude increased soon after the coursework; the percentage of change was 77% and 43% respectively. However, significant reductions in knowledge and attitude scores were observed 2–3 years after the coursework compared to scores soon after the coursework. The reduction was higher for attitude scores; knowledge and attitude scores have decreased by 10% and 37% respectively. The change in scores across assessments is evident from the graph, and clearly the effect size is higher for attitude than knowledge.

The scores of knowledge or attitude before the coursework did not significantly differ with respect to gender or age or were not correlated with years of experience. Hence, they were not considered as covariates in the above analysis.

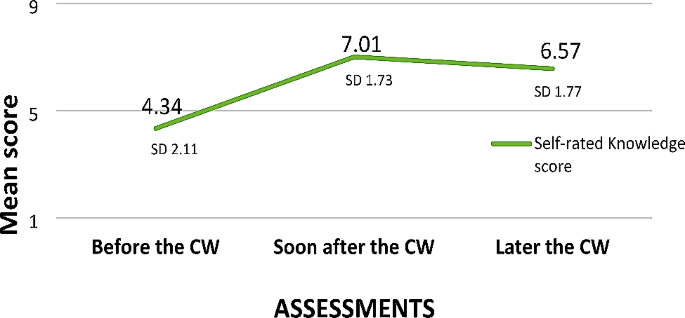

A semi structured questionnaire with open ended questions was also administered to elicit in-depth information about the usefulness of the coursework programme, in which they were also asked to self- rate their knowledge. The data were mostly categorical or narratives. Research scholars’ self-rated knowledge scores (on a scale of 0–10) also showed similar changes; knowledge improved significantly and was retained even after the training (Fig. 2 ).

Self-rated knowledge scores of research scholars over time. Later the CW – 2–3 years after the coursework

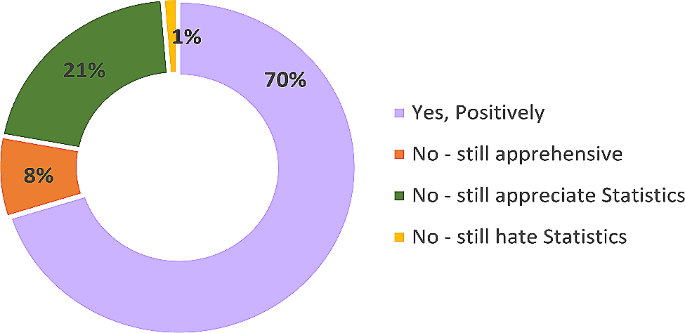

The response to the question “ How has coursework changed your attitude toward statistics?”, is presented in Fig. 3 . The responses were Yes, positively, Yes - Negatively, No change – still apprehensive, No change – still appreciate, No change – still hate statistics. The majority of the scholars (70%) reported a positive change in their attitude toward statistics. Moreover, none of the scholars reported negative changes. Approximately 9% of the scholars reported that they were still apprehensive about statistics or hate statistics after the coursework.

How has coursework changed your attitude toward statistics?

Those scholars who reported that they were apprehensive about statistics or hate statistics noted the complexity of the subject, lack of clarity, improper instructions and fear of mathematics as major reasons for their attitude. Some responses are listed below.

“The statistical concepts were not taught in an understandable manner from the UG level” , “I am weak in mathematical concepts. The equations and formulae in statistics scare me”. “Lack of knowledge about the importance of statistics and fear of mathematical equations”. “The preconceived notion that Statistics is difficult to learn” . “In most of the places, it is not taught properly and conceptual clarity is not focused on, and because of this an avoidance builds up, which might be a reason for the negative attitude”.

Majority of the scholars (92%) felt that coursework has helped them in their PhD, and they were happy to recommend it for other research scholars (97%). The responses of the scholars to the question “ How was coursework helpful in your PhD journey ?”, are listed below.

“Course work gave a fair idea on various things related to research as well as statistics” . “Creating the best design while planning methodology, which is learnt form course work, will increase efficiency in completing the thesis, thereby making it faster”. “Course work give better idea of how to proceed in many areas like literature search, referencing, choosing statistical methods, and learning about research procedures”. “Course work gave a good idea of research methodology, biostatistics and ethics. This would help in writing a better protocol and a better thesis”. “It helps us to plan our research well and to formulate, collect and plan for analysis”. “It makes people to plan their statistical analysis well in advance” .

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the existing coursework programme in an institution of higher medical education, and investigated whether the coursework programme benefits research scholars by improving their knowledge of statistics and attitudes towards statistics. The study concluded that the coursework program was beneficial for improving scholars’ knowledge about statistics and attitudes toward statistics.

Unlike other studies that have assessed attitudes toward statistics, the study participants in this study were research scholars. Research scholars need extensive training in statistics, as they need to apply statistical tests and use statistical reasoning in their research thesis, and in their profession to design research projects or their future student dissertations. Notably, no studies have assessed the attitudes or knowledge of research scholars in statistics either across the PhD training period or after intensive statistics training programs. However, the findings of this study are consistent with the findings of a study that compared the knowledge and attitudes toward teaching and education design of PhD students after a two-day educational course and instructional design workshop [ 14 ].

Statistics educators need not only impart knowledge but they should also motivate the learners to appreciate the role of statistics and to continue to learn the quantitative skills that is needed in their professional lives. Therefore, the role of learners’ attitudes toward statistics requires special attention. Since PhD coursework is possibly a major contributor to creating a statistically literate research community, scholars’ attitudes toward statistics need to be considered important and given special attention. Passionate and engaging statistics educators who have adequate experience in illustrating relatable examples could help scholars feel less anxious and build competence and better attitudes toward statistics. Statistics educators should be aware of scholars’ anxiety, fears and attitudes toward statistics and about its influence on learning outcomes and further interest in the subject.

Strengths and limitations

Analysis of changes in knowledge and attitudes scores across various time points of PhD training is the major strength of the study. Additionally, this study evaluates the effectiveness of intensive statistical courses for research scholars in terms of changes in knowledge and attitudes. This study has its own limitations: the data were collected through online platforms, and the nonresponse rate was about 38%. Ability in mathematics or prior learning experience in statistics, interest in the subject, statistics anxiety or performance in coursework were not assessed; hence, their influence could not be studied. The reliability and validity of the knowledge questionnaire have not been established at the time of this study. However, author who had prepared the questionnaire had ensured questions from different areas of statistics that were covered during the coursework, it has also been used as part of the coursework evaluation. Despite these limitations, this study highlights the changes in attitudes and knowledge following an intensive training program. Future research could investigate the roles of age, sex, mathematical ability, achievement or performance outcomes and statistics anxiety.

The study concluded that a rigorous and intensive training program such as PhD coursework was beneficial for improving knowledge about statistics and attitudes toward statistics. However, the significant reduction in attitude and knowledge scores after 2–3 years of coursework indicates that a refresher program might be helpful for research scholars as they approach the analysis stage of their thesis. Statistics educators must develop innovative methods to teach research scholars from nonstatistical backgrounds. They also must be empathetic to understanding scholars’ anxiety, fears and attitudes toward statistics and to understand its influence on learning outcomes and further interest in the subject.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

UGC Regulations on Minimum Standards and Procedure for the award of, M.Phil/Ph D, Degree R. 2009. Ugc.ac.in. [cited 2023 Oct 26]. https://www.ugc.ac.in/oldpdf/regulations/mphilphdclarification.pdf .

Althubaiti A. Attitudes of medical students toward statistics in medical research: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. J Stat Data Sci Educ [Internet]. 2021;29(1):115–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2020.1850220 .

Hannigan A, Hegarty AC, McGrath D. Attitudes towards statistics of graduate entry medical students: the role of prior learning experiences. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2014;14(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-70 .

Hasabo EA, Ahmed GEM, Alkhalifa RM, Mahmoud MD, Emad S, Albashir RB et al. Statistics for undergraduate medical students in Sudan: associated factors for using statistical analysis software and attitude toward statistics among undergraduate medical students in Sudan. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2022;22(1):889. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03960-0 .

Zhang Y, Shang L, Wang R, Zhao Q, Li C, Xu Y et al. Attitudes toward statistics in medical postgraduates: measuring, evaluating and monitoring. BMC Med Educ [Internet]. 2012;12(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-117 .

Bechrakis T, Gialamas V, Barkatsas A. Survey of attitudes towards statistics (SATS): an investigation of its construct validity and its factor structure invariance by gender. Int J Theoretical Educational Pract. 2011;1(1):1–15.

Google Scholar

Khavenson T, Orel E, Tryakshina M. Adaptation of survey of attitudes towards statistics (SATS 36) for Russian sample. Procedia Soc Behav Sci [Internet]. 2012; 46:2126–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.440 .

Coetzee S, Van Der Merwe P. Industrial psychology students’ attitudes towards statistics. J Industrial Psychol. 2010;36(1):843–51.

Francesca C, Primi C. Assessing statistics attitudes among College Students: Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Survey of attitudes toward statistics (SATS). Learn Individual Differences. 2009;2:309–13.

Counsell A, Cribbie RA. Students’ attitudes toward learning statistics with R. Psychol Teach Rev [Internet]. 2020;26(2):36–56. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsptr.2020.26.2.36 .

Yoon E, Lee J. Attitudes toward learning statistics among social work students: Predictors for future professional use of statistics. J Teach Soc Work [Internet]. 2022;42(1):65–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2021.2014018 .

Melad AF. Students’ attitude and academic achievement in statistics: a Correlational Study. J Posit School Psychol. 2022;6(2):4640–6.

Cook KD, Catanzaro BA. Constantly Working on My Attitude Towards Statistics! Education Doctoral Students’ Experiences with and Motivations for Learning Statistics. Innov High Educ. 2023; 48:257–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-022-09621-w .

Sohrabi Z, Koohestani HR, Nahardani SZ, Keshavarzi MH. Data on the knowledge, attitude, and performance of Ph.D. students attending an educational course (Tehran, Iran). Data Brief [Internet]. 2018; 21:1325–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.08.081 .

Chau C, Stevens J, Dauphine T. Del V. A: The development and validation of the survey of attitudes toward statistics. Educ Psychol Meas. 1995;(5):868–75.

Student attitude surveys. and online educational consulting [Internet]. Evaluationandstatistics.com. [cited 2023 Oct 26]. https://www.evaluationandstatistics.com/ .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the participants of the study and peers and experts who examined the content of the questionnaire for their time and effort.

This research did not receive any grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Biostatistics, Dr. M.V. Govindaswamy Centre, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, 560 029, India

Mariyamma Philip

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Mariyamma Philip: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing- Original draft, Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mariyamma Philip .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study used data already collected data (before and soon after coursework). The data pertaining to knowledge and attitude towards statistics 2–3 years after coursework were collected from research scholars through the online survey platform Google forms. The participants were invited to participate in the survey through e-mail. The study was explained in detail, and participation in the study was completely voluntary. Informed consent was obtained online in the form of a statement of consent. The confidentiality of the data was assured, even though identifiable personal information was not collected. This non-funded study was reviewed and approved by NIMHANS Institute Ethics Committee (No. NIMHANS/21st IEC (BS&NS Div.)

Consent for publication

Not applicable because there is no personal information or images that could lead to the identification of a study participant.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Philip, M. Measurement and analysis of change in research scholars’ knowledge and attitudes toward statistics after PhD coursework. BMC Med Educ 24 , 512 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05487-y

Download citation

Received : 27 October 2023

Accepted : 29 April 2024

Published : 08 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05487-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.