An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Internet Res

- v.22(4); 2020 Apr

Social Media Strategies for Health Promotion by Nonprofit Organizations: Multiple Case Study Design

Isabelle vedel.

1 Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

2 Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada

Jui Ramaprasad

3 Desautels Faculty of Management, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Liette Lapointe

Associated data.

Detailed presentation of each case.

Data collection tools.

Coding scheme.

Quotes from key informants.

Data dossier.

Nonprofit organizations have always played an important role in health promotion. Social media is widely used in health promotion efforts. However, there is a lack of evidence on how decisions regarding the use of social media are undertaken by nonprofit organizations that want to increase their impact in terms of health promotion.

The aim of this study was to understand why and how nonprofit health care organizations put forth social media strategies to achieve health promotion goals.

A multiple case study design, using in-depth interviews and a content analysis of each social media strategy, was employed to analyze the use of social media tools by six North American nonprofit organizations dedicated to cancer prevention and management.

The resulting process model demonstrates how social media strategies are enacted by nonprofit organizations to achieve health promotion goals. They put forth three types of social media strategies relative to their use of existing information and communication technologies (ICT)—replicate, transform, or innovate—each affecting the content, format, and delivery of the message differently. Organizations make sense of the social media innovation in complementarity with existing ICT.

Conclusions

For nonprofit organizations, implementing a social media strategy can help achieve health promotion goals. The process of social media strategy implementation could benefit from understanding the rationale, the opportunities, the challenges, and the potentially complementary role of existing ICT strategies.

Introduction

Nonprofit organizations have always played an important role in health promotion, such as advertising campaigns using billboards [ 1 ], radio [ 2 ], or television [ 3 ]. However, many health promotion programs run by nonprofit organizations have difficulty achieving success. This can be attributed to challenges with disseminating information to the appropriate target group, often because the target audience is not easily identifiable [ 4 ], or individuals ignoring information and not feeling engaged [ 1 ].

As a complement to more traditional information and communication technologies (ICT), social media is creating opportunities to address these challenges. Social media “encompasses a wide range of online, word-of-mouth forums” [ 5 ] and is characterized by its interactive and digital nature [ 6 ]. Nonprofit organizations are increasingly relying on social media to effectively design health promotion strategies [ 7 - 9 ] and to facilitate the reach of word of mouth [ 10 ], although some such organizations are not necessarily leveraging all the power social media can offer [ 11 ].

To date, research has mainly examined patients’ and professionals’ motives, barriers, and facilitators to the use of social media [ 12 - 15 ], as well as its impacts, both positive and negative [ 16 ]. On the one hand, social media has positive impacts for patients, such as enabling them to share experiences, seek information and opinions, engage with peers and providers, and belong to a community [ 14 , 16 - 19 ]. This, in turn, can improve patients’ sense of participation, motivation, autonomy, empowerment, perceived self-efficacy engagement in decision making, emotional support, and self-care [ 14 , 16 - 18 ]. These factors associated with social media can contribute to a positive impact on patient health: if social media enables patients to be more engaged in their health, they will change their behavior more easily [ 17 ]. However, there is also the risk of unreliable and incorrect health information provided by the community for the community [ 20 ].

What is not clear from this literature is how decisions regarding the use of social media are undertaken by nonprofit organizations that want to increase their impact in terms of health promotion. Our study, conducted in the context of cancer, aims at understanding why and how nonprofit organizations develop social media strategies, with the goal of eliciting how such organizations can successfully leverage social media. Looking at the use of social media from the organizational perspective allows us to understand the characteristics of the social media strategies that are utilized by nonprofit organizations and to identify how social media may help organizations attain their goals of health promotion. This understanding is critical in providing guidance on how such organizations can leverage social media and manipulate the factors or change the conditions of their social media use to ultimately increase their impact on health promotion.

We conducted a multiple case study to examine how six North American nonprofit cancer organizations engage in the use of social media for health promotion.

Theoretical Framework

Our study is based on the organizing vision theoretical lens [ 21 ], which leverages the concept of mindfulness. In a learning organization, there is a commitment on learning and communication. The leadership of such organizations associate learning to organizational success and to sustaining a supportive learning culture [ 22 ]. Organizational mindfulness is “a combination of ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations, continuous refinement and differentiation of expectations based on newer experiences, willingness and capability to invent new expectations that make sense of unprecedented events” [ 23 ]. Hence, although a learning organization is focused on ensuring organizational memory , the construct of mindfulness embeds, in addition, a prospective and innovative perspective. The concept of mindfulness has proven to be useful to shed light not only on the organizational adoption of ICT innovations but also to inform how organizations can chart a successful course for ICT implementations, by remaining vigilant vis-à-vis ICT evolution [ 21 , 24 - 27 ]. To the best of our knowledge, this lens has not been used to examine social media.

Mindful behaviors of organizations mean openness to new information and awareness of multiple perspectives [ 28 ]. Mindful organizations are described as those that make appropriate interpretations of their nature and needs and respond adaptively to changes in their environment [ 29 ]. Rooted in this perspective, the organizing vision is a lens that helps explain how organizations can implement ICT innovations mindfully [ 30 ]. It shows how mindful organizations can become increasingly attentive to their idiosyncrasies and environment, to make the most of their ICT investments [ 31 ]. Mindfully innovating with ICT means that the organization “attends to an IT [Information Technology] innovation with reasoning grounded in its own organizational facts and specifics” [ 30 ], whereas innovating mindlessly with ICT refers to the instance where “a firm’s actions betray an absence of such attention and grounding” [ 30 ].

Leveraging on the organizing vision lens, we adopted a theory-building approach, based on a multiple case study design [ 32 , 33 ].

The six cases in this study were selected based on a maximum variation sampling strategy [ 34 ] and focused on organizations using social media for cancer prevention and management ( Table 1 ), a major public health issue in our society [ 35 ]. A detailed description of the key characteristics of each case is provided in Multimedia Appendix 1 , including the rationale of social media use and the ICT and social media tools used.

Case characteristics and social media tools used.

Data Sources and Data Collection

We triangulated our data sources: semistructured interviews with key informants, analysis of the documentation (eg, documentation describing the organization, reports, and newsletters), and qualitative content analysis of the websites and the social media tools used (eg, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube). In each organization, we conducted semistructured interviews with the chief executive officer or the person responsible for the social media development and use (ie, the key informants) in winter 2008-2009 [ 34 ]. These respondents had a thorough knowledge of the origins, implementation, use, barriers, and enabling factors of ICT and social media usage in their respective organizations. Our interview guide ( Multimedia Appendix 2 ) was validated and refined using four pilot interviews. The interviews lasted 1 hour on average and were recorded and transcribed verbatim in their entirety. In addition, we asked our participants to provide relevant documentation. We also collected data from the social media tools across 1 calendar year (2012), to minimize biases. In the end, for each organization, we created a data dossier that provides a structured summary of the characteristics of the organization, content of the website, and social media tools ( Multimedia Appendix 2 ). The overall data collection process resulted in several hundred pages of transcripts and social media content data dossiers.

Analytic induction was deemed to provide the best analytic strategy for this study [ 34 , 36 - 38 ]. Indeed, analytic induction begins with a deductive phase [ 34 , 39 ], which allows for the use of existing theory, and is followed by an inductive phase that allows for new insights to emerge from the data. Following the data collection process, we proceeded with the first round of coding of the social media data dossier and interview transcripts. Our initial codes were deductively based on the categories derived from our organizing vision theoretical lens to understand how organizations learned to best exploit social media through comprehension, adoption, implementation, and assimilation. Next, we proceeded to a round of open coding and identified new themes (eg, actions, tools, and practices put in place). Afterward, following axial coding, codes with the same content and meaning were grouped in higher-level categories (eg, rationale for using social media tools, complementarity with existing ICT, and challenges). Finally, through selective coding, we linked the resulting categories to the main category (eg, strategies). The analysis of the documentation was used to provide additional information and to corroborate and validate the information gathered via the interviews and the social media data dossier. During the overall process of data coding, as a team, we reviewed and discussed the codification of data until we had reached a consensus; this helped eliminate any potential discrepancy. Examples of codes are provided in Multimedia Appendix 3 . N’Vivo 9 (QRS International Pty Ltd) was used to support the coding and analysis of the transcripts.

The analysis followed an iterative process, from reading the data to the data analysis multiple times. This iteration allowed a progressive theory development process with an increasing level of abstraction [ 40 ], that is, the creation of a shared understanding that forms a coherent structure, a unified whole. This was repeated until theoretical saturation (ie, the point at which additional analysis repeatedly confirmed the interpretations already made) [ 41 ]. Following this iterative analysis process, we developed our process model of social media strategies for health promotion by nonprofit organizations.

Overall Findings

Overall, the analysis allowed us to build upon the four pillars of our organizing vision theoretical lens. First, we saw how organizations need to comprehend how social media can—or cannot—apply to their needs and reality in terms of health promotion. Second, mindful ICT adoption signifies the ability “to anchor the decision in local particulars, rather than simply follow the lead and public rationales or prior adopters” [ 31 ]. Third, in implementing social media, organizations have to be sensitive to their reality and idiosyncrasies. Finally, the mindfulness challenge in assimilation is to decide how to optimally integrate social media into everyday operations to have a better impact on health promotion. We provide illustrative quotes in Multimedia Appendix 4 and examples from the data dossier in Multimedia Appendix 5 .

The cross-case analysis—of the ICT and social media tools, interviews, and documents—revealed no major variation in the results among cases based on the cancer type they were concerned with, the country the organization is based in, the nature of the social media tools the organization employed, or the organization size. Although some of the larger organizations were able to assign some nonspecialized personnel to their social media activities, these activities mainly consisted of feeding the social media platforms, not developing the social media strategy. The analysis of the data dossiers did not reveal any major differences in why and how nonprofit organizations develop social media strategies.

Comprehension

Organizations tend to have one or several of the five following rationales for the adoption of social media in health promotion:

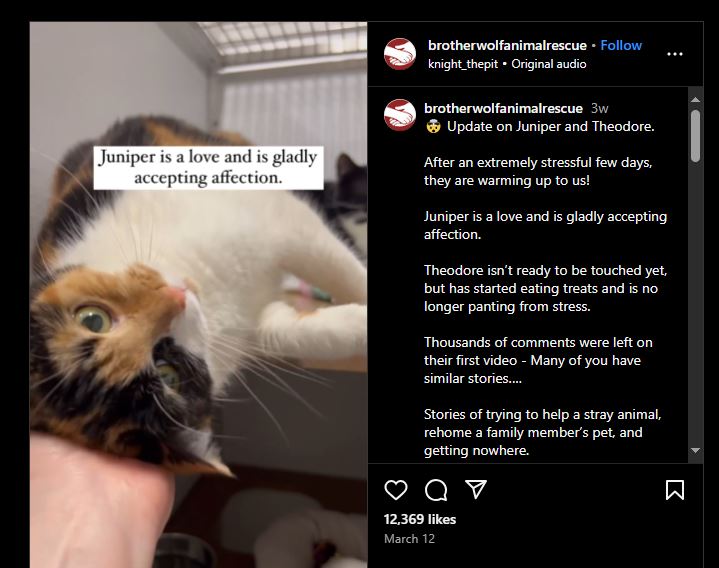

- Creating awareness: Organizations use social media tools to advertise about the disease and to promote healthy behaviors (eg, screening). Social media can be particularly useful to provide information that can be tailored to a specific audience and to reach people who are not voluntarily seeking the information (see quotes 1-3 in Multimedia Appendix 4 ).

- Educating: Social media tools can provide up-to-date information on the disease (eg, risk factors) and can enable end users (patients, families, and significant others) to make better informed decisions (eg, about treatment options—see quotes 4 and 5).

- Providing a forum to interact and support: Social media tools such as blogs, forums, or tweets allow users to get advice from the organization and to facilitate user interactions among themselves for support (see quotes 6-8).

- Advocating: Social media tools are also, at times, used to play an activist role in relation to the organizations’ missions (see quotes 9 and 10).

- Raising funds: Social media could be a way to facilitate communications and connections with donors (see quotes 11-13). Organizations may also track and report on social media metrics (eg, number of tweets and retweets), for the purposes of board and donor accountability.

In addition, six important opportunities associated with the use of the social media tools were identified:

- Ease-of-use: Social media tools are perceived to be easy to use and provide the opportunity to easily reach a large number of individuals, as evidenced by the number of fans, followers, posts, and blogs (see quote 14 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Low cost: Social media is seen as a low-cost tool compared with traditional marketing tools. For small organizations with limited budgets, such low-cost tools provide new opportunities to communicate and provide information (see quotes 15 and 16).

- Interactivity with end users: Social media provides a forum for individuals to connect with each other and to engage in more personalized discussions in a timely manner (see quotes 17 and 18). Data show active participation of users ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ) and better effectiveness. For example, end users can follow links and choose the path of information that they would like to explore deeper (see quotes 19 and 20).

- Flexibility: Social media tools do not impose a strict structure on how the tools are used, how individuals choose to interact and access information using these tools, and how they are integrated with other media (see quotes 21 and 22). This was further evidenced by the links for YouTube videos that were found on many Facebook pages ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Status: The use of social media tools was associated with a desire for status differentiation and perceptions of popularity, trendiness, reputation, efficiency, etc (see quotes 23 and 24).

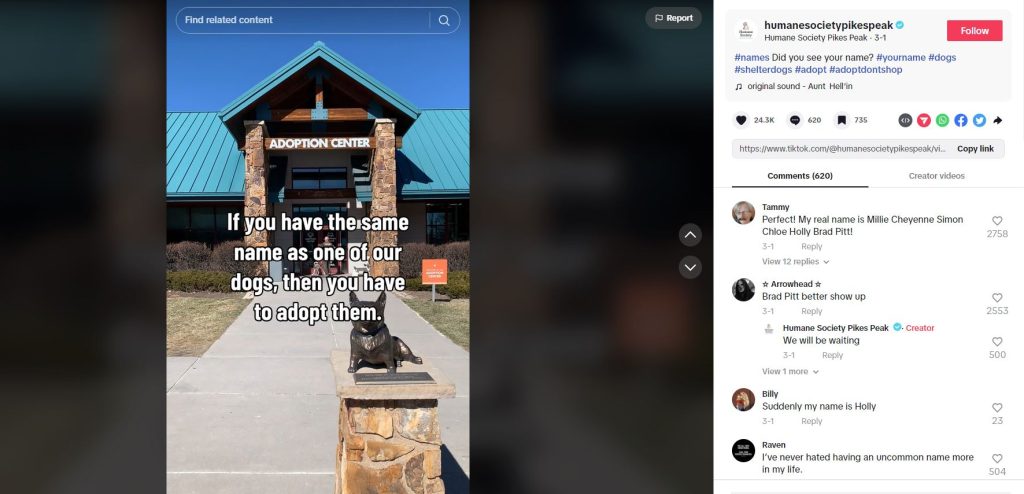

- Virability: Social media’s increased ease in spreading information compared with more traditional ICT—what we call virability—was evidenced by the ability to repost information on Facebook and Twitter ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ), sometimes through mobile devices (see quotes 25 and 26).

To maximize the impact, all six organizations used social media tools in addition to some ICT tools (eg, webpages and electronic newsletters) and even more traditional communication tools (eg, posters, magazine, and television advertisements; see quotes 27, 28, and 29 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ). They saw social media as a way to add to what they were already doing, to give more strength to their activities, and to augment and expand the capabilities of the ICT tools (see quotes 30-32). Concretely, analysis revealed three specific social media strategies :

- Replicate: Organizations essentially imitate their existing use of ICTs, but through a different channel to reach a different and broader audience (see quotes 33 and 34).

- Transform: Organizations use social media for the same purpose as it uses ICT tools, but the message is transformed in the way it is formatted and delivered, to better engage end users (see quotes 35 and 36).

- Innovate: To truly tap in the soul of social media, organizations modify the message or action for a new purpose, seeking different results. Such a strategy entails, for example, reposting a message, taking advantage of the virability of the media, and using blogs for press conferences or virtual billboards for advertising. Altogether such a strategy may ultimately enable the development of a community (see quotes 37 and 38).

Implementation

To better take into account the reality of their usage and context, organizations have had to deal with several challenges :

- Lack of control: Managing the openness in communication that is enabled through social media ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ) and appropriately monitor the quality, quantity, and format of conversations individuals were having (see quotes 39 and 40). This difficulty concerns both the user contribution and the information that the organization and partners themselves provided (see quotes 41 and 42).

- Technology-related issues: Although user friendly, technology usage introduces challenges such as forced upon updates and characteristics that create limitations (see quotes 43 and 44).

- Diversity of audience: Reaching a wider audience creates challenges in tailoring the message to different communities (eg, an older population and less educated individuals; see quotes 45 and 46 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Availability of resources: Finding the resources to develop and manage social media was considered challenging, given the need to find individuals with the expertise in both the content (cancer) and the social media tool. Moreover, there is a need to maintain a social media presence at a high level of interactivity, which requires an extensive amount of time (see quotes 47-50).

- Difficulty in measuring impacts: It is difficult to define relevant indicators of success and objectively assess whether social media use truly helps meet goals (see quotes 51 and 52).

Assimilation

In assimilation, organizations decide how to optimally integrate the new social media tools into everyday operations.

- Mindless/mindful: At the onset, organizations did not necessarily adopt or use social media in a well thought-out manner, with clear objectives in mind. Actually, the initial use of social media in most of the organizations was primarily mindless. This was particularly noticeable in the case of two organizations where the decision to use social media was not a planned event and where social media strategies were enacted to seize emergent opportunities (see quotes 53 and 54). The level of mindfulness of social media use by the organizations we studied evolved. With time, some organizations were beginning to reflect more about social media (see quotes 55 and 56). Interestingly, in the organization that was most mindful at the onset, social media usage continued to evolve in the same manner, maintaining a mindful stance (see quote 57).

- Reactive/proactive: Above and beyond the mindful/mindless stance of the process, our results show that the social media strategies were at times enacted in a reactive manner and at other times in a proactive manner. Social media strategies were initially implemented mainly in a reactive manner (ie, in response to users’ explicit needs; see quote 58). Only one organization exhibited goal-directed behavior and demonstrated anticipation—a proactive orientation—that is, enabling change before such needs are overtly expressed (see quote 59).

Connecting the Dots

In summary, our data revealed that in addition to considering the level of mindfulness, it was important to consider the proactiveness, or lack thereof, exhibited by the organizations. We linked the strategies put forth by organizations to their overall level of mindfulness and proactive orientation ( Figure 1 ).

Mindfulness and proactive orientation of the six cases. BCA: Breast Cancer Action; BCF: Breast Cancer Foundation; PCF: Prostate Cancer Foundation; PFP: Pints for Prostate; UsT: Us Too International.

We identified three clusters:

- Cluster 1: The organization exhibits a low level of mindfulness and little proactiveness. The only strategy that was mobilized is this case was replicate. Hence, this organization mostly used social media to carry on the same activities but using social media (see quotes 60-62).

- Cluster 2: One organization exhibited a fairly low level of mindfulness but a high proactive orientation; another organization exhibited a low proactive orientation but a higher level of mindfulness. In both cases, these organizations leverage social media to transform their message, using the particularities of social media to better engage users (see quotes 63 and 64). Despite the fact that these organizations are not both proactive and mindful, they do appear to derive higher value from their social media strategies in terms of health promotion (see quotes 65 and 66) than organizations exhibiting a low level of mindfulness and little proactiveness (ie, cluster 1).

- Cluster 3: Organizations exhibit a higher level of mindfulness compared with the other clusters. In all, three organizations did not use social media simply to replicate or to transform their message but most importantly to innovate by leveraging the potential offered by social media (see quote 67 and 68). Not surprisingly, these organizations appear to derive the most value from their involvement in social media (see quotes 69 and 70).

The Process Model of Social Media Strategies for Health Promotion by Nonprofit Organizations

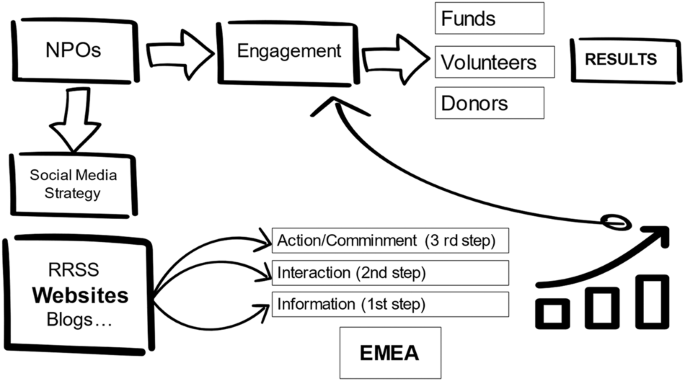

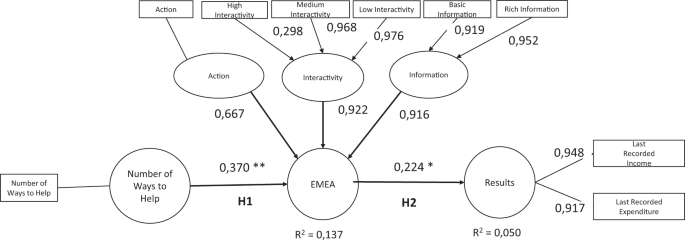

On the basis of our data analysis and the organizing vision theoretical lens, we developed a process model that reveals the elements and patterns of relationships that underlie the enactment of social media strategies by organizations for health promotion ( Figure 2 ).

Process model of social media strategies for health promotion by nonprofit organizations.

It first shows that the four pillars of social media strategy enactment— comprehension , adoption , implementation , and assimilation —are not necessarily observed sequentially. Instead, they are intertwined, can occur in any order, and are often iterative. As such, assimilation can occur anywhere in the social media enactment process.

Our model also shows that the organizations need to comprehend the rationales and opportunities linked with social media tools. They develop their social media strategies (replicate, transform, innovate) based on the complementarities they seek between existing ICT and social media, which will affect the content, the format, and the delivery of the message ( Table 2 ). Our model also shows that to leverage their social media strategies , organizations also need to balance opportunities with the inherent challenges of social media.

Social media strategies: key message characteristics in the synergistic use of information and communication technologies and social media tools.

This social media enactment process is also embedded in the orientation— proactive vs reactive —and the level of mindfulness vs mindlessness in which social media strategies are put in place, as illustrated in Table 3 .

Reactive/proactive and mindless/mindful social media strategies enactment.

When organizations are mindless and reactive (type 1), they generally go with the flow , that is, they observe and follow what is happening in the field. When organizations are more proactive, although still mindless (type 2), they do not have a clear plan for their social media strategy. Regardless, they attempt to stay in the forefront of their social media use and iteratively adjust their subsequent social media decisions on a trial-and-error basis. When organizations are mindful and reactive (type 3), they are observing others’ usage of social media and assessing its potential value. They then decide whether and how to engage in implementing their social media strategy, thus making an informed decision but without a clear and definite plan of action. The final category (type 4) is when organizations are self-aware, staying on the edge, and create a clearly defined strategy . They then act with foresight, in a strategic and rational manner, which occurs when organizations are proactive and mindful.

Principal Findings

Understanding how social media strategies are enacted and how social media can be strategically leveraged at the organizational level is an understudied area of research in health care. Recent work has established the importance of social media for patients and professionals to enable interactions and to access information [ 14 ]. We complement this work by looking at social media adoption by nonprofit cancer organizations—institutions that are central in health promotion. The goals of this study were to understand why and how six organizations put forth and enact social media strategies to achieve health promotion goals. Our analysis revealed five main rationales for adoption of social media, as described above, and a process of organizational adoption that we visualize in Figure 2 . A key aspect of the all the rationales identified is that they have the common goal of enabling interaction with patients, families, and members of the community for reasons ranging from creating awareness and educating individuals to raising funds for the organizations.

This study adds to the existing literature around patient and professional use of social media [ 14 , 42 ] and extends it by delving deep into the process of adoption of social media by nonprofit organizations. In doing this, we not only look at social media by itself but also its use alongside other ICT tools [ 43 ]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has taken this approach, which provides an overarching view of the social media adoption process by organizations, a comprehensive understanding of opportunities and challenges associated with adoption of social media, and practical implications for managers who seek to use social media.

One of our key findings in this study is that to leverage their social media strategies, organizations need to balance opportunities with the inherent challenges of social media, such as lack of control [ 44 ], risk of misinformation, lack of privacy, limited audience, usability of social media programs, and the manipulation of identity [ 17 ]. With the recent attention to the spread of misinformation on the Web, organizations must understand and implement mechanisms to combat the risks associated with misinformation and privacy. It is critical that information is disseminated from credible sources, such as the organizations that we studied, using tools and technologies that end users, such as patients and their families, can access.

Furthermore, when studying organizational social media use, the question of how organizations should communicate with stakeholders is vital [ 45 ]. Results from our study suggest that it is imperative to consider the existing ICT when adopting a social media strategy. Our results shows that depending on the complementarity sought by the concomitant use of ICT and social media [ 46 ], organizations will seek to create the optimal synergy between the two strategies when interacting with users, which is consistent with current research findings that suggest that ICT provides most value when combined with other existing resources in the organization [ 46 ]. In developing social media strategies that take this complementarity into account, organizations must consider the capabilities of the tools along three dimensions: the content, the format, and the delivery [ 47 , 48 ]. Indeed, “...strategies do not need to be drastically overhauled to incorporate social media but merely retooled in framing messages and targeting audiences using the new media” [ 49 ].

Overall, although some organizations embrace social media to be at the forefront of innovation to provide health promotion, for others, social media adoption appears to be more of a bandwagon effect. Organizations feel pressure to use social media as they see their competitors and peers using it. In making decisions about social media, organizations face a highly ambiguous environment because of its novelty. Indeed, at the organizational level, the impacts of social media strategies, and their benefits and risks, are still uncertain. Previous research indicates that under high-ambiguity conditions, bandwagon pressures tend to increase [ 28 ]. In addition, it has been said that the idea of “mindlessness in innovating with IT [Information Technologies] can reasonably be entertained whenever and wherever its likely rewards outweigh its risks” [ 30 ]. However, with time, as the understanding of social media and its role at the organizational level becomes clearer, it is to be expected that organizations would move toward enacting more mindful and proactive social media strategies. Indeed, “mindfulness is not something that an organization possesses: Instead, it is something that emerges in a process of becoming” [ 50 ]. Our results suggest that a proactive/mindful stance contributes to improve health promotion.

These results also pave the way for future research, such as testing the model using a larger sample to understand how this process may change depending on the type of organizations (eg, public health agencies, hospitals, private health care organizations, and bigger organization with dedicated staff for the social media activities). Moreover, it would be interesting to take into account the material properties of the social media tools themselves [ 51 - 53 ]. In that perspective, a study of the affordances of each social media tool could be insightful.

Our process model of social media strategies for health promotion by nonprofit organizations provides a means for managers of nonprofit organizations to understand the rationale of social media strategies and the role that social media can play in health promotion. Our process model can also be used as a guiding framework for nonprofit organizations engaging in social media use for health promotion. These organizations often face the challenge of effectively disseminating information to and engaging with the correct target group, all at low cost. This study provides these organizations with a mechanism for assessing how they can best exploit social media, taking into consideration the opportunities and challenges they face and the complementarities with their existing ICT. Using and understanding these mechanisms can help them create a well-defined strategy that will permit synergies between the existing ICT and social media, so that the use of both sets of tools together will bring in benefits that will surpass the simple sum of each.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by a William Dawson Scholar Award (McGill University). Isabelle Vedel also received a New Investigator Salary Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors would like to thank Marine Hardouin and Andrea Zdyb for their help in editing this manuscript.

Abbreviations

Multimedia appendix 1, multimedia appendix 2, multimedia appendix 3, multimedia appendix 4, multimedia appendix 5.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

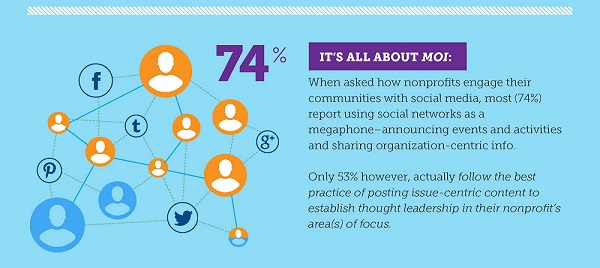

Social Media’s Purpose in Nonprofit Donor Engagement

March 21, 2017.

by Heather Weathers

Introduction

It’s no surprise that marketing methods have increasingly focused attention on digital marketing through social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Many nonprofit organizations have followed this pattern and attempted to integrate social media into traditional donor development models. Despite their efforts, many organizations have still seen steep declines in donor retention rates and are struggling to engage younger millennial audiences (Donor Retention, 2009).

Where does social media fit?

Donor identification and development has historically been based on donor pyramids, ladders and funnels which organize donors from least engaged (i.e. smallest donation amounts) to most engaged (major donations). Many organizations have integrated social media onto the bottom rungs of these traditional models (Dixon and Keyes, 2013). However, in 2010 Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide teamed up with Georgetown University’s Center for Social Impact Communication and found that most Americans’ first interaction with a nonprofit was not social-media driven. In fact, only 18 percent of respondents first became involved by engaging with a nonprofit organization via a social media outlet such as Facebook (Ogilvy, 2011).

These so-called “slacktivists” have been assumed to do nothing more than “like” an organization or update a profile picture for the cause but eschew more traditional methods of involvement such as volunteering time or donating money. So where does social media fit in donor development? Are nonprofit employees wasting their limited time and resources on a medium with no return on investment?

The Ogilvy/Georgetown study (2011) found that contrary to the slacktivist portrayal of an individual who “likes” a cause on Facebook but has no further engagement, their research found that Americans who engaged with a cause on social media were also most likely to participate in cause-related activities such as volunteering or donating money outside of social media. For these individuals, social media is simply being added to the list of activities that they already participate in for the cause, including giving money.

These individuals were most likely donors or volunteers first who then became more involved in the cause by promoting the organization via social media. Most individuals have no interest in engaging in conversations or relationships with large “faceless” corporations on Facebook (Vorvoreanu, 2009).

Social media is a useful tool to help existing donors and volunteers influence others for the cause. However, this has not typically been the current usage trend among nonprofit organizations (Dixon, 2013).

What’s wrong with current nonprofit social media strategies?

Social media engagement is typically seen as a low-involvement activity. In contrast, encouraging others to donate money is a high-involvement activity. It is easy to share a post or “like” a page. These low-involvement activities are appealing to nonprofit communicators because they are simple and straightforward. To simply ask followers to “share” and “like” posts does not require communicators and development departments to work across each other (Dixon, 2013). For most nonprofit communicators, low-involvement activities such as liking an organization on social media is generally seen as the first-step toward moving a donor to higher-influence activities such as asking others to donate to the organization.

However, Dixon and Keyes found that “there is a noticeable lack of activities that fall into the low involvement, high influence quadrant, because for an activity to be influential, it needs to be grounded in authenticity and personal commitment. A person can be involved but not influential, but can never be influential without being involved.”

Current social media usage trends for nonprofit organizations involve numerous low-involvement activities in an attempt to drive awareness of a cause. Most nonprofit organizations used Facebook to drive top-down communication similar to traditional media usage to drive traffic and attention to the brand. In contrast most nonprofits Facebook fans shared specific events and highlighted their own personal involvement (Das, 2010).

Most nonprofit social media campaigns focus on three types of posting: Information, Community and Action (Lovejoy and Saxton, 2012).

- Information : almost 60 percent of the top 100 organizations’ tweets were providing information about the organizations’ activities or latest news.

- Community : Only 25 percent of most organizations’ tweets fostered any type of dialogue or invited community building in the digital sphere. Types of community-building posts or tweets include recognition and thanks to specific people or companies, responding to public messages or acknowledging current events.

- Action : About 15 percent of organization’s messages focused on getting people to do something for the organization such as donate money, buy a t-shirt or attend a fundraising event.

What do people want?

Email is most donors’ most preferred communication method – even among Millenial donors where 93 percent favored email over Facebook and print communication (Case, 2010). Most individuals use social media for three reasons: to feel connected, for entertainment and for self-affirmation (Leung, 2001).

Variable 1: Connectedness

Social networking is primarily used to stay in contact with people who are already seen frequently by the user (Lenhart and Madden, 2007).

Variable 2: Entertainment

The main motive for joining Facebook is peer pressure and the main gratifications people receive when using Facebook include entertainment and staying informed in social circles (Quan-Haase and Young, 2010). Among those over age 50, the two primary factors in Facebook usage are mood management including entertainment such as games and social action such as reposting political opinions (Ancu, 2012).

Variable 3: Self-affirmation

The “hipster” effect is the idea that the more connected someone appears to be in causes actually increases a person’s social capital (Ellison, et al., 2007). This self-affirmation theory was used to determine that spending time on Facebook fulfilled an ego need and that exposure to one’s own Facebook profile increased self-worth and self-integrity (Toma and Hancock, 2013).

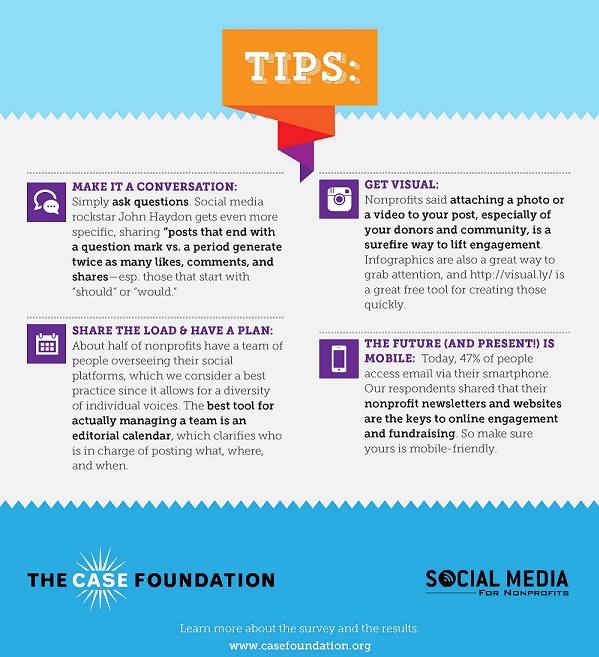

How can nonprofit organizations improve their social media strategies?

Social media is constantly changing and it can be overwhelming to consider all of the options and tools available for organizations to reach their target audiences. Organizations can incorporate these elements into their social media strategy to help produce real results:

- Start at the beginning. The first step in building a good social media strategy starts with a good donor strategy. Entry points for engagement into a nonprofit are not confined to a particular level. In fact, most people enter at various levels, such as both a volunteer and a social media supporter. Often people have multiple levels of engagement with an organization at one time (Ogilvy, 2011). An organization’s goal is to offer supporters a variety of involvements that engage their strengths and abilities to have an impact (Dixon and Keyes, 2013).

- Involvement first. Most people who donate online, “like” an organization’s Facebook page or follow an organization through any social media were first involved in some other connection to the organization such as being a volunteer, attending meetings or in leadership (board member, committee member, etc.) (Reddick and Ponomariov, 2013). Social media outlets are an additional element similar to a newsletter, a phone call or a face-to-face meeting used to engage in meaningful conversations with people already connected to the organization.

- Target the right people. It is important to prioritize where the organization’s audience spends most of their time with social media (Moravick, 2010). If they are using Twitter, then the organization should follow their accounts and tweet pictures of the individual or company in action as volunteers or sponsors of events. If the organizations’ corporate partners are using Facebook, the organization should tag them in “thank you” posts with pictures that show how their money has impacted lives. Organizations may not need to use more than two or three social media outlets to reach the largest portion of their donors and volunteers.

- “You cannot manage what you don’t measure” (PR News, 2009). Look at where traffic from specific sites is coming from and where messages are going. To do this, use “tagged links” through Google Analytics or find a favorite method of tracking all social media outlets including the organization’s newsletter. After acquiring the data, organizations should ask themselves: is this traffic useful? If they are getting good data, organizations will probably rethink some of their social media outlets and strategy (PR News, 2009).

- Reassess and re-evaluate. Once organizations have built a strategy, involved their constituents in meaningful communication and have the numbers to prove it, the audience’s interests will change again. Organizations should build re-evaluation methods and mobility into their strategy to allow the flexibility to change strategies at any time (Greenberg and Kates, 2014).

If social media has not revolutionized the way people get involved with nonprofit organizations, where should it fit in an organization’s strategy?

Most organizations have two social media audiences: their current supporters and their supporters’ network. There are several ways to engage these two audiences depending on the cause, the social media outlet, and the supporters themselves (Dixon and Keyes, 2013).

Current Supporters

There are typically five ways in which a social-media supporter first becomes involved with supporting causes: donating money (40 percent), talking to others about the cause (40 percent), learning more about the cause and its impact (37 percent), donating clothing or other items (30 percent), and signing a petition (27 percent) (Ogilvy, 2011).

Social media can be a meaningful conversation with people who are already engaged with an organization as a donor, volunteer or member. This strategy creates an environment of continuous communication that donors demand (Case, 2009).

Current Supporters Network

“Friend-raising” can be a powerful element to social media (Daniels, 2010). When an audience feels engaged and empowered to help a cause that they feel passionate about, they are more likely to involve their friends. Organizations can turn the role of fundraiser from a solely internal function of the organization to a role that’s shared by everyone in his or her community by preparing social media material that is easily redistributed, straightforward and directly shares the impact of the cause such as stories of those who need help or have been helped by the organization (Saxton and Wang, 2014).

Nearly three-quarters of Millenials said they would tell Facebook friends about great nonprofit events, and 65 percent said they would promote a nonprofit’s great story or accomplishment. In addition, 61 percent said they would use Facebook to alert friends to volunteering opportunities and needs (Case, 2012).

Eighty-six percent of nonprofit professionals report that their organizations use social media in some form. However, most nonprofits dedicate less than the equivalent of one half of one full-time employee to overseeing social media efforts. In addition, more than 60 percent allot no extra budget dollars to such efforts (Soder, 2009).

The key is for nonprofit organizations to find their audience, begin a conversation with them and empower them to bring others into the dialogue.

Scholarly (Peer-reviewed)

- Ancu, M. (2012). Older Adults on Facebook: A Survey Examination of Motives and Use of Social Networking by People 50 and Older. Florida Communication Journal , 40(2), 1-12

- Das, A. (2010). Facebook and Nonprofit Organizations: A Content Analysis. Conference Papers — International Communication Association , 1.

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 12, 1143-1168.

- Leung, L.(2001).College student motives for chatting on ICQ. New Media & Society, 3, 483-500

- Lovejoy, K., & Saxton, G. D. (2012). Information, community, and action: How nonprofit organizations use social media. Journal of Computer ‐ Mediated Communication, 17 (3), 337-353.

- Ogilvy Public Relations Worldwide, Georgetown University Center for Social Impact Communication. (2011). Dynamics of Cause Engagement. Retrieved from http://csic.georgetown.edu/research/digital-persuasion/dynamics-of-cause-engagement

- Quan-Haase, A., Young, A. (2010). Uses and Gratifications of Social Media: A Comparison of Facebook and Instant Messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30: 350- 361

- Reddick, C. G., & Ponomariov, B. (2013;2012;). The effect of individuals’ organization affiliation on their internet donations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42 (6), 1197-1223.

- Saxton, G. D., & Wang, L. (2014). The social network effect: The determinants of giving through social media. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43 (5), 850-868.

- Toma, Catalina L. & Hancock, Jeffrey T. (2013). Self Affirmation Underlies Facebook Use. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, March 2013; vol. 39, 3: pp. 321-331.,

- The Case Foundation. (2015). Millenial Impact Report . Retrieved from http://fi.fudwaca.com/mi/files/2015/07/2015-MillennialImpactReport.pdf

- Vorvoreanu, M. (2009). Perceptions of Corporations on Facebook: An Analysis of Facebook Social Norms. Journal Of New Communications Research , 4(1), 67-86.

Trade Publications

- Case study: Metrics make the world go ’round: How one nonprofit measures the impact of its social media marketing. (2009). PR News, 65 (17)

- Daniels, C. (2010, 07). Nonprofits discover power of social media fundraising. PRweek, 13 , 18.

- Dixon, J., & Keyes, D. (2013, Winter). The permanent disruption of social media. Stanford Social Innovation Review,11 , 24-29.

- Donor retention an issue, even as online donations rise. (2009). Nonprofit Business Advisor , (236), 5-9.

- Greenberg, E., & Kates, A. (2014). Strategic digital marketing: Top digital experts share the formula for tangible returns on your marketing investment . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lenhart, A., &Madden, M.( 2007a, July 1). Social networking websites and teens: An overview (Report). Washington, DC : Pew Internet and American Life Project . Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/ppf/r/198/report_display.asp

- Moravick, A. (2010). Nonprofits look to up their social media game. Promo (Online)

- Soder, C. (2009). Social media become key tool for nonprofits. Crain’s Cleveland Business, 30 (45), 5.

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 6.4.2020 in Vol 22 , No 4 (2020) : April

Social Media Strategies for Health Promotion by Nonprofit Organizations: Multiple Case Study Design

Authors of this article:

Original Paper

- Isabelle Vedel 1, 2 * , MD, PhD ;

- Jui Ramaprasad 3 * , BS, PhD ;

- Liette Lapointe 3 * , BA, MSc, PhD

1 Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

2 Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada

3 Desautels Faculty of Management, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

*all authors contributed equally

Corresponding Author:

Isabelle Vedel, MD, PhD

Department of Family Medicine

McGill University

5858 Chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges, 3rd Fl

Montreal, QC, H3S 1Z1

Phone: 1 5143999107

Email: [email protected]

Background: Nonprofit organizations have always played an important role in health promotion. Social media is widely used in health promotion efforts. However, there is a lack of evidence on how decisions regarding the use of social media are undertaken by nonprofit organizations that want to increase their impact in terms of health promotion.

Objective: The aim of this study was to understand why and how nonprofit health care organizations put forth social media strategies to achieve health promotion goals.

Methods: A multiple case study design, using in-depth interviews and a content analysis of each social media strategy, was employed to analyze the use of social media tools by six North American nonprofit organizations dedicated to cancer prevention and management.

Results: The resulting process model demonstrates how social media strategies are enacted by nonprofit organizations to achieve health promotion goals. They put forth three types of social media strategies relative to their use of existing information and communication technologies (ICT)—replicate, transform, or innovate—each affecting the content, format, and delivery of the message differently. Organizations make sense of the social media innovation in complementarity with existing ICT.

Conclusions: For nonprofit organizations, implementing a social media strategy can help achieve health promotion goals. The process of social media strategy implementation could benefit from understanding the rationale, the opportunities, the challenges, and the potentially complementary role of existing ICT strategies.

Introduction

Nonprofit organizations have always played an important role in health promotion, such as advertising campaigns using billboards [ 1 ], radio [ 2 ], or television [ 3 ]. However, many health promotion programs run by nonprofit organizations have difficulty achieving success. This can be attributed to challenges with disseminating information to the appropriate target group, often because the target audience is not easily identifiable [ 4 ], or individuals ignoring information and not feeling engaged [ 1 ].

As a complement to more traditional information and communication technologies (ICT), social media is creating opportunities to address these challenges. Social media “encompasses a wide range of online, word-of-mouth forums” [ 5 ] and is characterized by its interactive and digital nature [ 6 ]. Nonprofit organizations are increasingly relying on social media to effectively design health promotion strategies [ 7 - 9 ] and to facilitate the reach of word of mouth [ 10 ], although some such organizations are not necessarily leveraging all the power social media can offer [ 11 ].

To date, research has mainly examined patients’ and professionals’ motives, barriers, and facilitators to the use of social media [ 12 - 15 ], as well as its impacts, both positive and negative [ 16 ]. On the one hand, social media has positive impacts for patients, such as enabling them to share experiences, seek information and opinions, engage with peers and providers, and belong to a community [ 14 , 16 - 19 ]. This, in turn, can improve patients’ sense of participation, motivation, autonomy, empowerment, perceived self-efficacy engagement in decision making, emotional support, and self-care [ 14 , 16 - 18 ]. These factors associated with social media can contribute to a positive impact on patient health: if social media enables patients to be more engaged in their health, they will change their behavior more easily [ 17 ]. However, there is also the risk of unreliable and incorrect health information provided by the community for the community [ 20 ].

What is not clear from this literature is how decisions regarding the use of social media are undertaken by nonprofit organizations that want to increase their impact in terms of health promotion. Our study, conducted in the context of cancer, aims at understanding why and how nonprofit organizations develop social media strategies, with the goal of eliciting how such organizations can successfully leverage social media. Looking at the use of social media from the organizational perspective allows us to understand the characteristics of the social media strategies that are utilized by nonprofit organizations and to identify how social media may help organizations attain their goals of health promotion. This understanding is critical in providing guidance on how such organizations can leverage social media and manipulate the factors or change the conditions of their social media use to ultimately increase their impact on health promotion.

We conducted a multiple case study to examine how six North American nonprofit cancer organizations engage in the use of social media for health promotion.

Theoretical Framework

Our study is based on the organizing vision theoretical lens [ 21 ], which leverages the concept of mindfulness. In a learning organization, there is a commitment on learning and communication. The leadership of such organizations associate learning to organizational success and to sustaining a supportive learning culture [ 22 ]. Organizational mindfulness is “a combination of ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations, continuous refinement and differentiation of expectations based on newer experiences, willingness and capability to invent new expectations that make sense of unprecedented events” [ 23 ]. Hence, although a learning organization is focused on ensuring organizational memory , the construct of mindfulness embeds, in addition, a prospective and innovative perspective. The concept of mindfulness has proven to be useful to shed light not only on the organizational adoption of ICT innovations but also to inform how organizations can chart a successful course for ICT implementations, by remaining vigilant vis-à-vis ICT evolution [ 21 , 24 - 27 ]. To the best of our knowledge, this lens has not been used to examine social media.

Mindful behaviors of organizations mean openness to new information and awareness of multiple perspectives [ 28 ]. Mindful organizations are described as those that make appropriate interpretations of their nature and needs and respond adaptively to changes in their environment [ 29 ]. Rooted in this perspective, the organizing vision is a lens that helps explain how organizations can implement ICT innovations mindfully [ 30 ]. It shows how mindful organizations can become increasingly attentive to their idiosyncrasies and environment, to make the most of their ICT investments [ 31 ]. Mindfully innovating with ICT means that the organization “attends to an IT [Information Technology] innovation with reasoning grounded in its own organizational facts and specifics” [ 30 ], whereas innovating mindlessly with ICT refers to the instance where “a firm’s actions betray an absence of such attention and grounding” [ 30 ].

Leveraging on the organizing vision lens, we adopted a theory-building approach, based on a multiple case study design [ 32 , 33 ].

The six cases in this study were selected based on a maximum variation sampling strategy [ 34 ] and focused on organizations using social media for cancer prevention and management ( Table 1 ), a major public health issue in our society [ 35 ]. A detailed description of the key characteristics of each case is provided in Multimedia Appendix 1 , including the rationale of social media use and the ICT and social media tools used.

Data Sources and Data Collection

We triangulated our data sources: semistructured interviews with key informants, analysis of the documentation (eg, documentation describing the organization, reports, and newsletters), and qualitative content analysis of the websites and the social media tools used (eg, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube). In each organization, we conducted semistructured interviews with the chief executive officer or the person responsible for the social media development and use (ie, the key informants) in winter 2008-2009 [ 34 ]. These respondents had a thorough knowledge of the origins, implementation, use, barriers, and enabling factors of ICT and social media usage in their respective organizations. Our interview guide ( Multimedia Appendix 2 ) was validated and refined using four pilot interviews. The interviews lasted 1 hour on average and were recorded and transcribed verbatim in their entirety. In addition, we asked our participants to provide relevant documentation. We also collected data from the social media tools across 1 calendar year (2012), to minimize biases. In the end, for each organization, we created a data dossier that provides a structured summary of the characteristics of the organization, content of the website, and social media tools ( Multimedia Appendix 2 ). The overall data collection process resulted in several hundred pages of transcripts and social media content data dossiers.

Analytic induction was deemed to provide the best analytic strategy for this study [ 34 , 36 - 38 ]. Indeed, analytic induction begins with a deductive phase [ 34 , 39 ], which allows for the use of existing theory, and is followed by an inductive phase that allows for new insights to emerge from the data. Following the data collection process, we proceeded with the first round of coding of the social media data dossier and interview transcripts. Our initial codes were deductively based on the categories derived from our organizing vision theoretical lens to understand how organizations learned to best exploit social media through comprehension, adoption, implementation, and assimilation. Next, we proceeded to a round of open coding and identified new themes (eg, actions, tools, and practices put in place). Afterward, following axial coding, codes with the same content and meaning were grouped in higher-level categories (eg, rationale for using social media tools, complementarity with existing ICT, and challenges). Finally, through selective coding, we linked the resulting categories to the main category (eg, strategies). The analysis of the documentation was used to provide additional information and to corroborate and validate the information gathered via the interviews and the social media data dossier. During the overall process of data coding, as a team, we reviewed and discussed the codification of data until we had reached a consensus; this helped eliminate any potential discrepancy. Examples of codes are provided in Multimedia Appendix 3 . N’Vivo 9 (QRS International Pty Ltd) was used to support the coding and analysis of the transcripts.

The analysis followed an iterative process, from reading the data to the data analysis multiple times. This iteration allowed a progressive theory development process with an increasing level of abstraction [ 40 ], that is, the creation of a shared understanding that forms a coherent structure, a unified whole. This was repeated until theoretical saturation (ie, the point at which additional analysis repeatedly confirmed the interpretations already made) [ 41 ]. Following this iterative analysis process, we developed our process model of social media strategies for health promotion by nonprofit organizations.

Overall Findings

Overall, the analysis allowed us to build upon the four pillars of our organizing vision theoretical lens. First, we saw how organizations need to comprehend how social media can—or cannot—apply to their needs and reality in terms of health promotion. Second, mindful ICT adoption signifies the ability “to anchor the decision in local particulars, rather than simply follow the lead and public rationales or prior adopters” [ 31 ]. Third, in implementing social media, organizations have to be sensitive to their reality and idiosyncrasies. Finally, the mindfulness challenge in assimilation is to decide how to optimally integrate social media into everyday operations to have a better impact on health promotion. We provide illustrative quotes in Multimedia Appendix 4 and examples from the data dossier in Multimedia Appendix 5 .

The cross-case analysis—of the ICT and social media tools, interviews, and documents—revealed no major variation in the results among cases based on the cancer type they were concerned with, the country the organization is based in, the nature of the social media tools the organization employed, or the organization size. Although some of the larger organizations were able to assign some nonspecialized personnel to their social media activities, these activities mainly consisted of feeding the social media platforms, not developing the social media strategy. The analysis of the data dossiers did not reveal any major differences in why and how nonprofit organizations develop social media strategies.

Comprehension

Organizations tend to have one or several of the five following rationales for the adoption of social media in health promotion:

- Creating awareness: Organizations use social media tools to advertise about the disease and to promote healthy behaviors (eg, screening). Social media can be particularly useful to provide information that can be tailored to a specific audience and to reach people who are not voluntarily seeking the information (see quotes 1-3 in Multimedia Appendix 4 ).

- Educating: Social media tools can provide up-to-date information on the disease (eg, risk factors) and can enable end users (patients, families, and significant others) to make better informed decisions (eg, about treatment options—see quotes 4 and 5).

- Providing a forum to interact and support: Social media tools such as blogs, forums, or tweets allow users to get advice from the organization and to facilitate user interactions among themselves for support (see quotes 6-8).

- Advocating: Social media tools are also, at times, used to play an activist role in relation to the organizations’ missions (see quotes 9 and 10).

- Raising funds: Social media could be a way to facilitate communications and connections with donors (see quotes 11-13). Organizations may also track and report on social media metrics (eg, number of tweets and retweets), for the purposes of board and donor accountability.

In addition, six important opportunities associated with the use of the social media tools were identified:

- Ease-of-use: Social media tools are perceived to be easy to use and provide the opportunity to easily reach a large number of individuals, as evidenced by the number of fans, followers, posts, and blogs (see quote 14 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Low cost: Social media is seen as a low-cost tool compared with traditional marketing tools. For small organizations with limited budgets, such low-cost tools provide new opportunities to communicate and provide information (see quotes 15 and 16).

- Interactivity with end users: Social media provides a forum for individuals to connect with each other and to engage in more personalized discussions in a timely manner (see quotes 17 and 18). Data show active participation of users ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ) and better effectiveness. For example, end users can follow links and choose the path of information that they would like to explore deeper (see quotes 19 and 20).

- Flexibility: Social media tools do not impose a strict structure on how the tools are used, how individuals choose to interact and access information using these tools, and how they are integrated with other media (see quotes 21 and 22). This was further evidenced by the links for YouTube videos that were found on many Facebook pages ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Status: The use of social media tools was associated with a desire for status differentiation and perceptions of popularity, trendiness, reputation, efficiency, etc (see quotes 23 and 24).

- Virability: Social media’s increased ease in spreading information compared with more traditional ICT—what we call virability—was evidenced by the ability to repost information on Facebook and Twitter ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ), sometimes through mobile devices (see quotes 25 and 26).

To maximize the impact, all six organizations used social media tools in addition to some ICT tools (eg, webpages and electronic newsletters) and even more traditional communication tools (eg, posters, magazine, and television advertisements; see quotes 27, 28, and 29 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ). They saw social media as a way to add to what they were already doing, to give more strength to their activities, and to augment and expand the capabilities of the ICT tools (see quotes 30-32). Concretely, analysis revealed three specific social media strategies :

- Replicate: Organizations essentially imitate their existing use of ICTs, but through a different channel to reach a different and broader audience (see quotes 33 and 34).

- Transform: Organizations use social media for the same purpose as it uses ICT tools, but the message is transformed in the way it is formatted and delivered, to better engage end users (see quotes 35 and 36).

- Innovate: To truly tap in the soul of social media, organizations modify the message or action for a new purpose, seeking different results. Such a strategy entails, for example, reposting a message, taking advantage of the virability of the media, and using blogs for press conferences or virtual billboards for advertising. Altogether such a strategy may ultimately enable the development of a community (see quotes 37 and 38).

Implementation

To better take into account the reality of their usage and context, organizations have had to deal with several challenges :

- Lack of control: Managing the openness in communication that is enabled through social media ( Multimedia Appendix 5 ) and appropriately monitor the quality, quantity, and format of conversations individuals were having (see quotes 39 and 40). This difficulty concerns both the user contribution and the information that the organization and partners themselves provided (see quotes 41 and 42).

- Technology-related issues: Although user friendly, technology usage introduces challenges such as forced upon updates and characteristics that create limitations (see quotes 43 and 44).

- Diversity of audience: Reaching a wider audience creates challenges in tailoring the message to different communities (eg, an older population and less educated individuals; see quotes 45 and 46 and Multimedia Appendix 5 ).

- Availability of resources: Finding the resources to develop and manage social media was considered challenging, given the need to find individuals with the expertise in both the content (cancer) and the social media tool. Moreover, there is a need to maintain a social media presence at a high level of interactivity, which requires an extensive amount of time (see quotes 47-50).

- Difficulty in measuring impacts: It is difficult to define relevant indicators of success and objectively assess whether social media use truly helps meet goals (see quotes 51 and 52).

Assimilation

In assimilation, organizations decide how to optimally integrate the new social media tools into everyday operations.

- Mindless/mindful: At the onset, organizations did not necessarily adopt or use social media in a well thought-out manner, with clear objectives in mind. Actually, the initial use of social media in most of the organizations was primarily mindless. This was particularly noticeable in the case of two organizations where the decision to use social media was not a planned event and where social media strategies were enacted to seize emergent opportunities (see quotes 53 and 54). The level of mindfulness of social media use by the organizations we studied evolved. With time, some organizations were beginning to reflect more about social media (see quotes 55 and 56). Interestingly, in the organization that was most mindful at the onset, social media usage continued to evolve in the same manner, maintaining a mindful stance (see quote 57).

- Reactive/proactive: Above and beyond the mindful/mindless stance of the process, our results show that the social media strategies were at times enacted in a reactive manner and at other times in a proactive manner. Social media strategies were initially implemented mainly in a reactive manner (ie, in response to users’ explicit needs; see quote 58). Only one organization exhibited goal-directed behavior and demonstrated anticipation—a proactive orientation—that is, enabling change before such needs are overtly expressed (see quote 59).

Connecting the Dots

In summary, our data revealed that in addition to considering the level of mindfulness, it was important to consider the proactiveness, or lack thereof, exhibited by the organizations. We linked the strategies put forth by organizations to their overall level of mindfulness and proactive orientation ( Figure 1 ).

We identified three clusters:

- Cluster 1: The organization exhibits a low level of mindfulness and little proactiveness. The only strategy that was mobilized is this case was replicate. Hence, this organization mostly used social media to carry on the same activities but using social media (see quotes 60-62).

- Cluster 2: One organization exhibited a fairly low level of mindfulness but a high proactive orientation; another organization exhibited a low proactive orientation but a higher level of mindfulness. In both cases, these organizations leverage social media to transform their message, using the particularities of social media to better engage users (see quotes 63 and 64). Despite the fact that these organizations are not both proactive and mindful, they do appear to derive higher value from their social media strategies in terms of health promotion (see quotes 65 and 66) than organizations exhibiting a low level of mindfulness and little proactiveness (ie, cluster 1).

- Cluster 3: Organizations exhibit a higher level of mindfulness compared with the other clusters. In all, three organizations did not use social media simply to replicate or to transform their message but most importantly to innovate by leveraging the potential offered by social media (see quote 67 and 68). Not surprisingly, these organizations appear to derive the most value from their involvement in social media (see quotes 69 and 70).

The Process Model of Social Media Strategies for Health Promotion by Nonprofit Organizations

On the basis of our data analysis and the organizing vision theoretical lens, we developed a process model that reveals the elements and patterns of relationships that underlie the enactment of social media strategies by organizations for health promotion ( Figure 2 ).

It first shows that the four pillars of social media strategy enactment— comprehension , adoption , implementation , and assimilation —are not necessarily observed sequentially. Instead, they are intertwined, can occur in any order, and are often iterative. As such, assimilation can occur anywhere in the social media enactment process.

Our model also shows that the organizations need to comprehend the rationales and opportunities linked with social media tools. They develop their social media strategies (replicate, transform, innovate) based on the complementarities they seek between existing ICT and social media, which will affect the content, the format, and the delivery of the message ( Table 2 ). Our model also shows that to leverage their social media strategies , organizations also need to balance opportunities with the inherent challenges of social media.

This social media enactment process is also embedded in the orientation— proactive vs reactive —and the level of mindfulness vs mindlessness in which social media strategies are put in place, as illustrated in Table 3 .

When organizations are mindless and reactive (type 1), they generally go with the flow , that is, they observe and follow what is happening in the field. When organizations are more proactive, although still mindless (type 2), they do not have a clear plan for their social media strategy. Regardless, they attempt to stay in the forefront of their social media use and iteratively adjust their subsequent social media decisions on a trial-and-error basis. When organizations are mindful and reactive (type 3), they are observing others’ usage of social media and assessing its potential value. They then decide whether and how to engage in implementing their social media strategy, thus making an informed decision but without a clear and definite plan of action. The final category (type 4) is when organizations are self-aware, staying on the edge, and create a clearly defined strategy . They then act with foresight, in a strategic and rational manner, which occurs when organizations are proactive and mindful.

Principal Findings

Understanding how social media strategies are enacted and how social media can be strategically leveraged at the organizational level is an understudied area of research in health care. Recent work has established the importance of social media for patients and professionals to enable interactions and to access information [ 14 ]. We complement this work by looking at social media adoption by nonprofit cancer organizations—institutions that are central in health promotion. The goals of this study were to understand why and how six organizations put forth and enact social media strategies to achieve health promotion goals. Our analysis revealed five main rationales for adoption of social media, as described above, and a process of organizational adoption that we visualize in Figure 2 . A key aspect of the all the rationales identified is that they have the common goal of enabling interaction with patients, families, and members of the community for reasons ranging from creating awareness and educating individuals to raising funds for the organizations.

This study adds to the existing literature around patient and professional use of social media [ 14 , 42 ] and extends it by delving deep into the process of adoption of social media by nonprofit organizations. In doing this, we not only look at social media by itself but also its use alongside other ICT tools [ 43 ]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has taken this approach, which provides an overarching view of the social media adoption process by organizations, a comprehensive understanding of opportunities and challenges associated with adoption of social media, and practical implications for managers who seek to use social media.

One of our key findings in this study is that to leverage their social media strategies, organizations need to balance opportunities with the inherent challenges of social media, such as lack of control [ 44 ], risk of misinformation, lack of privacy, limited audience, usability of social media programs, and the manipulation of identity [ 17 ]. With the recent attention to the spread of misinformation on the Web, organizations must understand and implement mechanisms to combat the risks associated with misinformation and privacy. It is critical that information is disseminated from credible sources, such as the organizations that we studied, using tools and technologies that end users, such as patients and their families, can access.

Furthermore, when studying organizational social media use, the question of how organizations should communicate with stakeholders is vital [ 45 ]. Results from our study suggest that it is imperative to consider the existing ICT when adopting a social media strategy. Our results shows that depending on the complementarity sought by the concomitant use of ICT and social media [ 46 ], organizations will seek to create the optimal synergy between the two strategies when interacting with users, which is consistent with current research findings that suggest that ICT provides most value when combined with other existing resources in the organization [ 46 ]. In developing social media strategies that take this complementarity into account, organizations must consider the capabilities of the tools along three dimensions: the content, the format, and the delivery [ 47 , 48 ]. Indeed, “...strategies do not need to be drastically overhauled to incorporate social media but merely retooled in framing messages and targeting audiences using the new media” [ 49 ].