- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2021

Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol

- Foluso Ishola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8644-0570 1 ,

- U. Vivian Ukah 1 &

- Arijit Nandi 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 192 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A country’s abortion law is a key component in determining the enabling environment for safe abortion. While restrictive abortion laws still prevail in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many countries have reformed their abortion laws, with the majority of them moving away from an absolute ban. However, the implications of these reforms on women’s access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes, is uncertain. First, there are methodological challenges to the evaluation of abortion laws, since these changes are not exogenous. Second, extant evaluations may be limited in terms of their generalizability, given variation in reforms across the abortion legality spectrum and differences in levels of implementation and enforcement cross-nationally. This systematic review aims to address this gap. Our aim is to systematically collect, evaluate, and synthesize empirical research evidence concerning the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs.

We will conduct a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on changes in abortion laws and women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will search Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, as well as grey literature and reference lists of included studies for further relevant literature. As our goal is to draw inference on the impact of abortion law reforms, we will include quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of change in abortion laws on at least one of our outcomes of interest. We will assess the methodological quality of studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series checklist. Due to anticipated heterogeneity in policy changes, outcomes, and study designs, we will synthesize results through a narrative description.

This review will systematically appraise and synthesize the research evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will examine the effect of legislative reforms and investigate the conditions that might contribute to heterogeneous effects, including whether specific groups of women are differentially affected by abortion law reforms. We will discuss gaps and future directions for research. Findings from this review could provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services and scale up accessibility.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019126927

Peer Review reports

An estimated 25·1 million unsafe abortions occur each year, with 97% of these in developing countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Despite its frequency, unsafe abortion remains a major global public health challenge [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the World health Organization (WHO), nearly 8% of maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion, with the majority of these occurring in developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Approximately 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from unsafe abortion such as hemorrhage, infections, septic shock, uterine and intestinal perforation, and peritonitis [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These often result in long-term effects such as infertility and chronic reproductive tract infections. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at US$ 232 million each year in developing countries [ 10 , 11 ]. The negative consequences on children’s health, well-being, and development have also been documented. Unsafe abortion increases risk of poor birth outcomes, neonatal and infant mortality [ 12 , 13 ]. Additionally, women who lack access to safe and legal abortion are often forced to continue with unwanted pregnancies, and may not seek prenatal care [ 14 ], which might increase risks of child morbidity and mortality.

Access to safe abortion services is often limited due to a wide range of barriers. Collectively, these barriers contribute to the staggering number of deaths and disabilities seen annually as a result of unsafe abortion, which are disproportionately felt in developing countries [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A recent systematic review on the barriers to abortion access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implicated the following factors: restrictive abortion laws, lack of knowledge about abortion law or locations that provide abortion, high cost of services, judgmental provider attitudes, scarcity of facilities and medical equipment, poor training and shortage of staff, stigma on social and religious grounds, and lack of decision making power [ 17 ].

An important factor regulating access to abortion is abortion law [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Although abortion is a medical procedure, its legal status in many countries has been incorporated in penal codes which specify grounds in which abortion is permitted. These include prohibition in all circumstances, to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, and on request with no requirement for justification [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Although abortion laws in different countries are usually compared based on the grounds under which legal abortions are allowed, these comparisons rarely take into account components of the legal framework that may have strongly restrictive implications, such as regulation of facilities that are authorized to provide abortions, mandatory waiting periods, reporting requirements in cases of rape, limited choice in terms of the method of abortion, and requirements for third-party authorizations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. For example, the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act permits abortion on socio-economic grounds. It is considered liberal, as it permits legal abortions for more indications than most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, abortions must only be provided in registered hospitals, and three medical doctors—one of whom must be a specialist—must provide signatures to allow the procedure to take place [ 22 ]. Given the critical shortage of doctors in Zambia [ 23 ], this is in fact a major restriction that is only captured by a thorough analysis of the conditions under which abortion services are provided.

Additionally, abortion laws may exist outside the penal codes in some countries, where they are supplemented by health legislation and regulations such as public health statutes, reproductive health acts, court decisions, medical ethic codes, practice guidelines, and general health acts [ 18 , 19 , 24 ]. The diversity of regulatory documents may lead to conflicting directives about the grounds under which abortion is lawful [ 19 ]. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, standards and guidelines on the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion supported by the constitution was contradictory to the penal code, leaving room for an ambiguous interpretation of the legal environment [ 25 ].

Regulations restricting the range of abortion methods from which women can choose, including medication abortion in particular, may also affect abortion access [ 26 , 27 ]. A literature review contextualizing medication abortion in seven African countries reported that incidence of medication abortion is low despite being a safe, effective, and low-cost abortion method, likely due to legal restrictions on access to the medications [ 27 ].

Over the past two decades, many LMICs have reformed their abortion laws [ 3 , 28 ]. Most have expanded the grounds on which abortion may be performed legally, while very few have restricted access. Countries like Uruguay, South Africa, and Portugal have amended their laws to allow abortion on request in the first trimester of pregnancy [ 29 , 30 ]. Conversely, in Nicaragua, a law to ban all abortion without any exception was introduced in 2006 [ 31 ].

Progressive reforms are expected to lead to improvements in women’s access to safe abortion and health outcomes, including reductions in the death and disabilities that accompany unsafe abortion, and reductions in stigma over the longer term [ 17 , 29 , 32 ]. However, abortion law reforms may yield different outcomes even in countries that experience similar reforms, as the legislative processes that are associated with changing abortion laws take place in highly distinct political, economic, religious, and social contexts [ 28 , 33 ]. This variation may contribute to abortion law reforms having different effects with respect to the health services and outcomes that they are hypothesized to influence [ 17 , 29 ].

Extant empirical literature has examined changes in abortion-related morbidity and mortality, contraceptive usage, fertility, and other health-related outcomes following reforms to abortion laws [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. For example, a study in Mexico reported that a policy that decriminalized and subsidized early-term elective abortion led to substantial reductions in maternal morbidity and that this was particularly strong among vulnerable populations such as young and socioeconomically disadvantaged women [ 38 ].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the growing literature on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes has not been systematically reviewed. A study by Benson et al. evaluated evidence on the impact of abortion policy reforms on maternal death in three countries, Romania, South Africa, and Bangladesh, where reforms were immediately followed by strategies to implement abortion services, scale up accessibility, and establish complementary reproductive and maternal health services [ 39 ]. The three countries highlighted in this paper provided unique insights into implementation and practical application following law reforms, in spite of limited resources. However, the review focused only on a selection of countries that have enacted similar reforms and it is unclear if its conclusions are more widely generalizable.

Accordingly, the primary objective of this review is to summarize studies that have estimated the causal effect of a change in abortion law on women’s health services and outcomes. Additionally, we aim to examine heterogeneity in the impacts of abortion reforms, including variation across specific population sub-groups and contexts (e.g., due to variations in the intensity of enforcement and service delivery). Through this review, we aim to offer a higher-level view of the impact of abortion law reforms in LMICs, beyond what can be gained from any individual study, and to thereby highlight patterns in the evidence across studies, gaps in current research, and to identify promising programs and strategies that could be adapted and applied more broadly to increase access to safe abortion services.

The review protocol has been reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 40 ] (Additional file 1 ). It was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database CRD42019126927.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies.

This review will consider quasi-experimental studies which aim to estimate the causal effect of a change in a specific law or reform and an outcome, but in which participants (in this case jurisdictions, whether countries, states/provinces, or smaller units) are not randomly assigned to treatment conditions [ 41 ]. Eligible designs include the following:

Pretest-posttest designs where the outcome is compared before and after the reform, as well as nonequivalent groups designs, such as pretest-posttest design that includes a comparison group, also known as a controlled before and after (CBA) designs.

Interrupted time series (ITS) designs where the trend of an outcome after an abortion law reform is compared to a counterfactual (i.e., trends in the outcome in the post-intervention period had the jurisdiction not enacted the reform) based on the pre-intervention trends and/or a control group [ 42 , 43 ].

Differences-in-differences (DD) designs, which compare the before vs. after change in an outcome in jurisdictions that experienced an abortion law reform to the corresponding change in the places that did not experience such a change, under the assumption of parallel trends [ 44 , 45 ].

Synthetic controls (SC) approaches, which use a weighted combination of control units that did not experience the intervention, selected to match the treated unit in its pre-intervention outcome trend, to proxy the counterfactual scenario [ 46 , 47 ].

Regression discontinuity (RD) designs, which in the case of eligibility for abortion services being determined by the value of a continuous random variable, such as age or income, would compare the distributions of post-intervention outcomes for those just above and below the threshold [ 48 ].

There is heterogeneity in the terminology and definitions used to describe quasi-experimental designs, but we will do our best to categorize studies into the above groups based on their designs, identification strategies, and assumptions.

Our focus is on quasi-experimental research because we are interested in studies evaluating the effect of population-level interventions (i.e., abortion law reform) with a design that permits inference regarding the causal effect of abortion legislation, which is not possible from other types of observational designs such as cross-sectional studies, cohort studies or case-control studies that lack an identification strategy for addressing sources of unmeasured confounding (e.g., secular trends in outcomes). We are not excluding randomized studies such as randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, or stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials; however, we do not expect to identify any relevant randomized studies given that abortion policy is unlikely to be randomly assigned. Since our objective is to provide a summary of empirical studies reporting primary research, reviews/meta-analyses, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, book reviews, correspondence, and case reports/studies will also be excluded.

Our population of interest includes women of reproductive age (15–49 years) residing in LMICs, as the policy exposure of interest applies primarily to women who have a demand for sexual and reproductive health services including abortion.

Intervention

The intervention in this study refers to a change in abortion law or policy, either from a restrictive policy to a non-restrictive or less restrictive one, or vice versa. This can, for example, include a change from abortion prohibition in all circumstances to abortion permissible in other circumstances, such as to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or on request with no requirement for justification. It can also include the abolition of existing abortion policies or the introduction of new policies including those occurring outside the penal code, which also have legal standing, such as:

National constitutions;

Supreme court decisions, as well as higher court decisions;

Customary or religious law, such as interpretations of Muslim law;

Medical ethical codes; and

Regulatory standards and guidelines governing the provision of abortion.

We will also consider national and sub-national reforms, although we anticipate that most reforms will operate at the national level.

The comparison group represents the counterfactual scenario, specifically the level and/or trend of a particular post-intervention outcome in the treated jurisdiction that experienced an abortion law reform had it, counter to the fact, not experienced this specific intervention. Comparison groups will vary depending on the type of quasi-experimental design. These may include outcome trends after abortion reform in the same country, as in the case of an interrupted time series design without a control group, or corresponding trends in countries that did not experience a change in abortion law, as in the case of the difference-in-differences design.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

Access to abortion services: There is no consensus on how to measure access but we will use the following indicators, based on the relevant literature [ 49 ]: [ 1 ] the availability of trained staff to provide care, [ 2 ] facilities are geographically accessible such as distance to providers, [ 3 ] essential equipment, supplies and medications, [ 4 ] services provided regardless of woman’s ability to pay, [ 5 ] all aspects of abortion care are explained to women, [ 6 ] whether staff offer respectful care, [ 7 ] if staff work to ensure privacy, [ 8 ] if high-quality, supportive counseling is provided, [ 9 ] if services are offered in a timely manner, and [ 10 ] if women have the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions, and receive answers.

Use of abortion services refers to induced pregnancy termination, including medication abortion and number of women treated for abortion-related complications.

Secondary outcomes

Current use of any method of contraception refers to women of reproductive age currently using any method contraceptive method.

Future use of contraception refers to women of reproductive age who are not currently using contraception but intend to do so in the future.

Demand for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one contraceptive method.

Unmet need for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to women of childbearing age.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death of newborn babies within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

There will be no language, date, or year restrictions on studies included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in a low- and middle-income country. We will use the country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify LMICs (Additional file 2 ).

Search methods

We will perform searches for eligible peer-reviewed studies in the following electronic databases.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946 to present)

Embase Classic+Embase on OvidSP (from 1947 to present)

CINAHL (1973 to present); and

Web of Science (1900 to present)

The reference list of included studies will be hand searched for additional potentially relevant citations. Additionally, a grey literature search for reports or working papers will be done with the help of Google and Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Search strategy

A search strategy, based on the eligibility criteria and combining subject indexing terms (i.e., MeSH) and free-text search terms in the title and abstract fields, will be developed for each electronic database. The search strategy will combine terms related to the interventions of interest (i.e., abortion law/policy), etiology (i.e., impact/effect), and context (i.e., LMICs) and will be developed with the help of a subject matter librarian. We opted not to specify outcomes in the search strategy in order to maximize the sensitivity of our search. See Additional file 3 for a draft of our search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Data management.

Search results from all databases will be imported into Endnote reference manager software (Version X9, Clarivate Analytics) where duplicate records will be identified and excluded using a systematic, rigorous, and reproducible method that utilizes a sequential combination of fields including author, year, title, journal, and pages. Rayyan systematic review software will be used to manage records throughout the review [ 50 ].

Selection process

Two review authors will screen titles and abstracts and apply the eligibility criteria to select studies for full-text review. Reference lists of any relevant articles identified will be screened to ensure no primary research studies are missed. Studies in a language different from English will be translated by collaborators who are fluent in the particular language. If no such expertise is identified, we will use Google Translate [ 51 ]. Full text versions of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on study eligibility criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or will involve a third reviewer as an arbitrator. The selection of studies, as well as reasons for exclusions of potentially eligible studies, will be described using a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

Data extraction will be independently undertaken by two authors. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two authors will meet with the third author to resolve any discrepancies. A piloted standardized extraction form will be used to extract the following information: authors, date of publication, country of study, aim of study, policy reform year, type of policy reform, data source (surveys, medical records), years compared (before and after the reform), comparators (over time or between groups), participant characteristics (age, socioeconomic status), primary and secondary outcomes, evaluation design, methods used for statistical analysis (regression), estimates reported (means, rates, proportion), information to assess risk of bias (sensitivity analyses), sources of funding, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers with content and methodological expertise in methods for policy evaluation will assess the methodological quality of included studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series risk of bias checklist [ 52 ]. This checklist provides a list of criteria for grading the quality of quasi-experimental studies that relate directly to the intrinsic strength of the studies in inferring causality. These include [ 1 ] relevant comparison, [ 2 ] number of times outcome assessments were available, [ 3 ] intervention effect estimated by changes over time for the same or different groups, [ 4 ] control of confounding, [ 5 ] how groups of individuals or clusters were formed (time or location differences), and [ 6 ] assessment of outcome variables. Each of the following domains will be assigned a “yes,” “no,” or “possibly” bias classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer with expertise in review methodology if required.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [ 53 ].

Data synthesis

We anticipate that risk of bias and heterogeneity in the studies included may preclude the use of meta-analyses to describe pooled effects. This may necessitate the presentation of our main findings through a narrative description. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles according to the following key headings:

Information on the differential aspects of the abortion policy reforms.

Information on the types of study design used to assess the impact of policy reforms.

Information on main effects of abortion law reforms on primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Information on heterogeneity in the results that might be due to differences in study designs, individual-level characteristics, and contextual factors.

Potential meta-analysis

If outcomes are reported consistently across studies, we will construct forest plots and synthesize effect estimates using meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed using the I 2 test where I 2 values over 50% indicate moderate to high heterogeneity [ 54 ]. If studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will use fixed effects. However, if there is evidence of heterogeneity, a random effects model will be adopted. Summary measures, including risk ratios or differences or prevalence ratios or differences will be calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analysis of subgroups

If there are sufficient numbers of included studies, we will perform sub-group analyses according to type of policy reform, geographical location and type of participant characteristics such as age groups, socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, education, or marital status to examine the evidence for heterogeneous effects of abortion laws.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted if there are major differences in quality of the included articles to explore the influence of risk of bias on effect estimates.

Meta-biases

If available, studies will be compared to protocols and registers to identify potential reporting bias within studies. If appropriate and there are a sufficient number of studies included, funnel plots will be generated to determine potential publication bias.

This systematic review will synthesize current evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health. It aims to identify which legislative reforms are effective, for which population sub-groups, and under which conditions.

Potential limitations may include the low quality of included studies as a result of suboptimal study design, invalid assumptions, lack of sensitivity analysis, imprecision of estimates, variability in results, missing data, and poor outcome measurements. Our review may also include a limited number of articles because we opted to focus on evidence from quasi-experimental study design due to the causal nature of the research question under review. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature, provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and discuss the potential effects of any limitations to our overall conclusions. Protocol amendments will be recorded and dated using the registration for this review on PROSPERO. We will also describe any amendments in our final manuscript.

Synthesizing available evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms represents an important step towards building our knowledge base regarding how abortion law reforms affect women’s health services and health outcomes; we will provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services, and scale up accessibility. This review will be of interest to service providers, policy makers and researchers seeking to improve women’s access to safe abortion around the world.

Abbreviations

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

Excerpta medica database

Low- and middle-income countries

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

International prospective register of systematic reviews

Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tuncalp O, Assifi A, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide; Global Incidence and Trends 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide . Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2018.

Book Google Scholar

Fusco CLB. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

Google Scholar

Rehnstrom Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):E323–E33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffikin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/11.2.117 .

Abiodun OM, Balogun OR, Adeleke NA, Farinloye EO. Complications of unsafe abortion in South West Nigeria: a review of 96 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):111–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13552 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vlassoff M, Walker D, Shearer J, Newlands D, Singh S. Estimates of health care system costs of unsafe abortion in Africa and Latin America. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(3):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409 .

Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding it up: costs and benefits of contraceptive services. Estimates for 2012. New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund; 2012.

Auger N, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Sauve R. Abortion and infant mortality on the first day of life. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442279 .

Krieger N, Gruskin S, Singh N, Kiang MV, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Reproductive justice & preventable deaths: state funding, family planning, abortion, and infant mortality, US 1980-2010. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:277–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.007 .

Banaem LM, Majlessi F. A comparative study of low 5-minute Apgar scores (< 8) in newborns of wanted versus unwanted pregnancies in southern Tehran, Iran (2006-2007). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(12):898–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802372390 .

Bhandari A. Barriers in access to safe abortion services: perspectives of potential clients from a hilly district of Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:87.

Seid A, Yeneneh H, Sende B, Belete S, Eshete H, Fantahun M, et al. Barriers to access safe abortion services in East Shoa and Arsi Zones of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Health Dev. 2015;29(1):13–21.

Arroyave FAB, Moreno PA. A systematic bibliographical review: barriers and facilitators for access to legal abortion in low and middle income countries. Open J Prev Med. 2018;8(5):147–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2018.85015 .

Article Google Scholar

Boland R, Katzive L. Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(3):110–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008 .

Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S, Johnson BR Jr, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0183-1 .

United Nations Population Division. Abortion policies: A global review. Major dimensions of abortion policies. 2002 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/abortion/abortion-policies-2002.asp .

Johnson BR, Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S. Global abortion policies database: a new approach to strengthening knowledge on laws, policies, and human rights standards. Bmc Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0174-2 .

Haaland MES, Haukanes H, Zulu JM, Moland KM, Michelo C, Munakampe MN, et al. Shaping the abortion policy - competing discourses on the Zambian termination of pregnancy act. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0908-8 .

Schatz JJ. Zambia’s health-worker crisis. Lancet. 2008;371(9613):638–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60287-1 .

Erdman JN, Johnson BR. Access to knowledge and the Global Abortion Policies Database. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;142(1):120–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12509 .

Cleeve A, Oguttu M, Ganatra B, Atuhairwe S, Larsson EC, Makenzius M, et al. Time to act-comprehensive abortion care in east Africa. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(9):E601–E2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30136-X .

Berer M, Hoggart L. Medical abortion pills have the potential to change everything about abortion. Contraception. 2018;97(2):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.12.006 .

Moseson H, Shaw J, Chandrasekaran S, Kimani E, Maina J, Malisau P, et al. Contextualizing medication abortion in seven African nations: A literature review. Health Care Women Int. 2019;40(7-9):950–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1608207 .

Blystad A, Moland KM. Comparative cases of abortion laws and access to safe abortion services in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22:351.

Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19(1):13–27.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Johnson BR, Mishra V, Lavelanet AF, Khosla R, Ganatra B. A global database of abortion laws, policies, health standards and guidelines. B World Health Organ. 2017;95(7):542–4. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.17.197442 .

Replogle J. Nicaragua tightens up abortion laws. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60011-7 .

Keogh LA, Newton D, Bayly C, McNamee K, Hardiman A, Webster A, et al. Intended and unintended consequences of abortion law reform: perspectives of abortion experts in Victoria, Australia. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017;43(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101541 .

Levels M, Sluiter R, Need A. A review of abortion laws in Western-European countries. A cross-national comparison of legal developments between 1960 and 2010. Health Policy. 2014;118(1):95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.06.008 .

Serbanescu F, Morris L, Stupp P, Stanescu A. The impact of recent policy changes on fertility, abortion, and contraceptive use in Romania. Stud Fam Plann. 1995;26(2):76–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137933 .

Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, Harper CC, Rana A, Gurung G, et al. Effects of Abortion Legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 .

Goncalves-Pinho M, Santos JV, Costa A, Costa-Pereira A, Freitas A. The impact of a liberalisation law on legally induced abortion hospitalisations. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:142–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.05.037 .

Latt SM, Milner A, Kavanagh A. Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0705-y .

Clarke D, Muhlrad H. Abortion laws and women’s health. IZA discussion papers 11890. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics; 2018.

Benson J, Andersen K, Samandari G. Reductions in abortion-related mortality following policy reform: evidence from Romania, South Africa and Bangladesh. Reprod Health. 2011;8(39). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-39 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj-Brit Med J. 2015;349.

William R. Shadish, Thomas D. Cook, Donald T. Campbell. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, New York; 2002.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098 .

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. The use of controls in interrupted time series studies of public health interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):2082–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy135 .

Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat. 1995;13(2):151–61.

Strumpf EC, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Fixed effects and difference in differences. In: Methods in Social Epidemiology ed. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass; 2017.

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: estimating the effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program. J Am Stat Assoc. 2010;105(490):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abadie A, Diamond A, Hainmueller J. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. Am J Polit Sci. 2015;59(2):495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116 .

Moscoe E, Bor J, Barnighausen T. Regression discontinuity designs are underutilized in medicine, epidemiology, and public health: a review of current and best practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(2):132–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.021 .

Dennis A, Blanchard K, Bessenaar T. Identifying indicators for quality abortion care: a systematic literature review. J Fam Plan Reprod H. 2017;43(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jfprhc-2015-101427 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Anton A, Choi A, Fournier JP, Geier AK, et al. The accuracy of Google Translate for abstracting data from non-English-language trials for systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2019.

Reeves BC, Wells GA, Waddington H. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: a checklist for classifying studies evaluating the effects on health interventions-a taxonomy without labels. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.016 .

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD .

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Genevieve Gore, Liaison Librarian at McGill University, for her assistance with refining the research question, keywords, and Mesh terms for the preliminary search strategy.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Santé (FRQS) PhD doctoral awards and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant, “Examining the impact of social policies on health equity” (ROH-115209).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Purvis Hall 1020 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1A2, Canada

Foluso Ishola, U. Vivian Ukah & Arijit Nandi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FI and AN conceived and designed the protocol. FI drafted the manuscript. FI, UVU, and AN revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Foluso Ishola .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:.

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist. This checklist has been adapted for use with systematic review protocol submissions to BioMed Central journals from Table 3 in Moher D et al: Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015 4:1

Additional File 2:.

LMICs according to World Bank Data Catalogue. Country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify low- and middle-income countries

Additional File 3: Table 1

. Search strategy in Embase. Detailed search terms and filters applied to generate our search in Embase

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ishola, F., Ukah, U.V. & Nandi, A. Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 10 , 192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Download citation

Received : 02 January 2020

Accepted : 08 June 2021

Published : 28 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01739-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Abortion law/policies; Impact

- Unsafe abortion

- Contraception

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 21 November 2018

Knowledge and attitude of women towards the legalization of abortion in the selected town of Ethiopia: a cross sectional study

- Tilahun Fufa Debela 1 &

- Misgun Shewangizaw Mekuria 2

Reproductive Health volume 15 , Article number: 190 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

11 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Unsafe abortion contributes to maternal deaths 13% globally and 25–35% of Ethiopia. By considering the problem of unsafe abortion, Ethiopia amended a law that permits abortion under certain circumstances. However, the country liberalized the service, women are still not using it. Therefore, the possible reason might be a lack of knowledge and attitude is a barrier that hinders women to use safe abortion.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Arba Minch town from January 02 to 17, 2017. Women in the reproductive age groups (15–49) who reside in the town for more than six months were included in the study. The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula. Five kebeles were selected using the lottery method from 11 kebeles. The proportional allocation of the sample was done for each kebeles. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Binary and multiple logistic analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with knowledge & attitude toward legalization of abortion.

A total of 576 women were responded to the question. The finding of our study showed that only 23.4% of women have knowledge about the legalization of abortion. Of all the respondents 323(56%) prefer abortion on demand to be legalized while about 241 (41.9%) do not prefer to be legalized. Again about 57% of women believe that women can use it but the rest 43% believe even if allowed women do not use it. From all participants, 59% don’t want to use by themselves and also, 53.3% don’t think that women would have the right to use the service or terminate their pregnancy even if the pregnancy fulfill the criteria. Ethnicity, marital status, and family size were the factors significantly associated with knowledge. Again, educational status, marital status and having knowledge about the legalization of abortion were a statistically significant association with the attitude.

The study indicated that knowledge of women toward the legalization of abortion was low but more than half of respondents prefer abortion on demand to be legalized.

Peer Review reports

Plain English summary

Unsafe abortion contributes about 13% of the global burden of maternal mortality and up to 25–35% of maternal deaths in Ethiopia. Sixty nine percent of Ethiopian women who experienced termination of pregnancy used unsafe abortion practices.

The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitude of women towards legalization of abortion and its associated factors. The data were collected voluntarily and women who were critically ill, unable to talk or listen were excluded from the study. To measure knowledge; first, we asked whether women were aware the current abortion law of Ethiopia; if they answered yes, we continued to ask the legal prerequisites in Ethiopia to interrupt pregnancy. Knowledge of women toward the legalization of abortion was measured by seven closed-ended questions. The answers for the seven questions were aggregated out of seven. Those respondents who score above the median knowledge level (median knowledge score = 4) were considered as having good knowledge and those who score less than the median score were classified as having poor knowledge toward abortion legislation.

The attitude of women toward abortion legislation was measured by asking five closed-ended questions with both positive and negative responses. Those women who agreed or answer positively, considered as positive attitude and those respondents disagreed or negatively responded were considered as a negative attitude.

Of the 576 respondents: only 23.4% of women have good knowledge and 56% prefer abortion on demand to be legalized. Forty-three percent of women do not want to use the service even if it was legalized. And, 53.3% of women don’t think that women would have the right to use the service even if the pregnancy fulfills the legal criteria. Knowledge of abortion legislation differs among ethnic group, marital status, and households with different family size. Again, level of education, marital status, and knowledge of women about legislation of abortion were the associated factors for the attitude of women.

In conclusion, knowledge of women toward the legalization of abortion was low but more than half of respondents prefer abortion on demand to be legalized.

Maternal mortality is a public health problem in the world, especially in developing countries. Each year more than half a million maternal death happen in the world. From this, 99% occur in developing countries [ 1 ]. Sub Saharan Africa and South Asian alone accounts for 84% global maternal deaths [ 2 , 3 ]. There are many factors contributing to maternal deaths, from these hemorrhages, infection during and after delivery and also unsafe abortion are among the leading cause of maternal death [ 4 ]. Unsafe abortion alone contributes about 13% of the global burden of maternal mortality [ 5 ]. According to World Health Organization, every year greater than 42 million pregnancies are terminated due to various reasons; from that, approximately 20 million are due to unsafe abortions and it is estimated about 80, 000 worldwide deaths from it [ 6 , 7 ].

In Ethiopia, the number of maternal deaths associated with complication of pregnancy and delivery is among the highest in the world [ 5 ]. In Ethiopia, the ratio of maternal mortality (MMR) is 412 per 100,000 live births [ 8 ]. Several studies indicate that unsafe abortion accounts for up to 25–35% of maternal deaths in Ethiopia [ 9 , 10 ]. Unsafe abortion complication found to be significant public health problems in Ethiopia, accounting for the higher proportion of maternal morbidity, mortality and gynaecological admissions [ 7 ]. It can be prevented and reduced by expanding and improving family planning services and choices. With a low modern contraceptive prevalence rate (4.8%) and a high total fertility rate (6.8–7%), a large number of Ethiopian women faced unwanted pregnancies [ 5 ]. Sixty nine percent of Ethiopian women who experienced termination of pregnancy used unsafe abortion practices rather than medically supervised abortion [ 2 , 5 ]. The reason behind might be the lack of knowledge and attitude of women toward the legalization of abortion.

Ethiopia amended abortion law in May 2005 under certain conditions. Abortion is now legal in cases of rape, incest or fetal impairment. In addition, a woman can legally terminate a pregnancy if her life or physical health is in danger, if she has physical or mental disabilities, or if she is a minor who is physically or mentally unprepared for childbirth [ 9 , 11 , 12 ].

Knowledge about abortion law among women is very important because it has implications for access to legal abortion services [ 13 ]. As outlined in the WHO guideline on safe abortion, the proportion of women with correct knowledge of the legal status of abortion are both indicators for measuring access to information about safe abortion [ 14 ]. Even when safe, legal abortion services are available, women who lack accurate information about the law may seek unsafe abortion because they do not know that they are eligible for the service or do not know the legal requirements for obtaining an abortion [ 15 ]. Knowledge alone is not guarantee to use any service; but the attitude determines.

Research on knowledge of abortion law and attitude of women towards the law may help to inform policy makers and education planners in Ethiopia. Unfortunately, not much research has been conducted in this area among the women in the country. The aim of this study was to investigate knowledge and attitude of women toward the abortion law. Furthermore this study also identifies the associated factors influencing knowledge and attitude of women toward the legalization abortion.

Study design and setting

A community based cross-sectional study design was conduct from January 02 to 17, 2017 in Arba Minch town. The Town is found 465 km from Addis Ababa (the capital city of Ethiopia) to the south. The town has 11 kebeles (the lower administrative unit of Ethiopia). According to population projection of the 2007 national census conducted by the central statistics agency of Ethiopia (CSA), there was an estimated population of 110,104 of whom 53,951 were men and 56,153 were women. From this, 21,360 were reproductive age women. There were 19,000 households in the town during the data collection period.

Study participants

The study population was women in reproductive-age who were living in the town for more than six months in the randomly selected kebeles of the town. The data were collected voluntarily and women who were critically ill, unable to talk or listen were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling method

The required sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula. The assumptions considered were; proportion (p) of 50%, a margin error of 5%, a design effect of 1.5 and none response rate of 10%. Accordingly, the sample size was: n = (1.96) 2 × 0.5 (1–0.5)/ (0.05) 2 ; n = 384, and by considering 10% no response rate and a design effect of 1.5 the total sample size was 633. A multistage sampling technique was used. Five kebeles out of 11 kebeles were randomly selected using the lottery method. List of reproductive age women was extracted from a community-based intervention for action (CBIA) data in the selected kebeles which were collected by health extension workers. The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated to each kebele. To have individual study subjects, systematic sampling method was employed during data collection with K value of 4 ( N = 2591 and n = 633 i.e. every 4th from the registration). The first woman was selected by lottery method.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected using field-tested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed after reviewing related literatures. The questionnaire has different sessions such as socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, 7 abortion history items, 5 attitude items and 7 items on knowledge questions. The questionnaire prepared in English was translated to Amharic (local language) and back to English in order to maintain consistency. Five data collectors those speak the local language (Amharic) collected the data with two supervisors.

Data analysis

Data were entered into EpiData v3.1, exported to SPSS version 21 and cleaned to check for completeness and missing values. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and summary statistics were used to describe the study population in relation to relevant variables. In binary logistic regression, both bivariate and multivariate analyses were carried out. All variables were entered into the bivariate analysis to identify the association between dependent and independent variables. Those explanatory variables with a p -value < 0.25 in the crude analysis had been used for multivariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, those variables with the p-value < 0.05 were considered as predictors of the legalization of abortion care.

Measurements

Knowledge of abortion legalization was measured by asking seven abortion legislation questions. Questions were developed based on reviewing the Ethiopian legislation for abortion and other similar studies [ 10 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. First, women asked whether they aware about the current abortion law of Ethiopia; if the woman answered yes, we continued to ask the legal prerequisites in Ethiopia to interrupt pregnancy to know their knowledge level. To assess knowledge of the abortion law, seven closed-ended questions were used. The answers for these seven questions were aggregated out of seven. Those respondents who score above the median knowledge level (median knowledge score = 4) were considered as having good knowledge and those who score less than the mean score were classified as having poor knowledge of abortion legislation.

The attitude of women toward abortion legislation was measured by asking five closed-ended questions with both positive and negative responses. Those women who agreed or answer positively, considered as a positive attitude and those respondents disagreed or negatively responded were considered as a negative attitude.

Data quality management

The questionnaires were pretested outside the study area. After the pretest, the questionnaire was reviewed for appropriateness of wording; clarity of both contents and whether instructions elicited is going with responses. Data collectors were trained for one day to be familiar with the data collection tool. Editing and sorting of the questionnaires were done to determine the completeness and consistency of data every day during the data collection. The completed questionnaires were cross-checked and made a correction on daily basis.

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 576 women were interviewed from five kebeles. The overall response rate was 91%. One hundred sixty seven (29%) of the respondents were in the age group of 35–39 with the mean age of 34.48 + 5.43. Forty-five percent of women were Gamo in ethnicity while 27.9% were Konso. One hundred sixty six (28.9%) of study participants were attended primary school. Two hundred sixty two (45.6%) and 246 (42.7%) were followers of protestant and Orthodox religions, respectively. Two hundred forty seven (69%) of the mothers are currently living with their husband. One hundred seventy-three (30%) of the study participants were government workers. Two hundred thirty two (40.4%) of the respondents earn monthly income of greater than 1500 Ethiopian Birr (27 Ethiopian Birr = 1 USD). Three hundred eighteen (55.2%) of the respondents had family size of 3–6 (Table 1 ).

Abortion history

Among women included in the study 476(82.6%) had ever pregnant while 159(27.6%) had the history of unwanted pregnancy. One hundred twenty five (21.6%) of respondents have had induced abortion. From the total study participants about ninety two (73.5%) use private health institution as the place of abortion. Two hundred seventy one (47.1%) of women want to continue if they had unwanted pregnancy; while 158 (27.6%) women desire to terminate. Among the respondents, 372 (64.6%) were using family planning (Table 2 ).

The attitude of women toward legalization of abortion

Among women included in the study 323(56%) prefer abortion on demand to be legalized while 241 (41.9%) do not prefer to be legalized. Out of the respondents 327 (56.8%) were think that if abortion is legally allowed people can use the service. Three hundred forty (59%) of respondents do not use the service by themselves if abortion is legally allowed and 308(53.4%) also do not think that woman have the right to terminate their pregnancy. Two hundred seventy (46.8%) do not agree if women decided for some reason to terminate their pregnancy (Table 3 ).

Knowledge of respondents toward legalization of abortion

Among the women included in the study 187 (32.5%) had ever heard about safe abortion while 389(67.5%) had none. Out of respondents who had ever heard about save abortion 107(19%) were heard from their friends. Three hundred ninety six (69%) of respondents didn’t know about the complication of abortion while only 180(31%) knew. From the respondents only 135(23.4%) of women knew whether abortion was legal in Ethiopia but, majorities (67%) of respondents did not knew. From those respondents who knew about legalization of abortion in Ethiopia, 108(80%), 80(59%), 114(84.4%) and 18(13%) mentioned that abortion is legal if it is by incest, has a problem on mother; by rape and mother didn’t want respectively. One hundred seventeen (86.7%) of respondents believe that abortion was decided by women themselves while 18(13.3%) of them by doctor /health professionals. According to 93(69%) of respondents the time of abortion was before 3 months of pregnancy (Table 4 ).

Factors associated with attitude toward legalization of abortion

All predictors of attitude toward legalization of abortion were entered into a logistic regression model and the final associated factors were identified. From those entered into the model, marital status, educational, pregnancy termination history and knowledge were statistically significant that affect the attitude of women toward legalization of abortion. The study revealed that single women and divorced were 81.9 and 93.1% times less likely had a good attitude as compared to married (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) = .181, 95% Confidence Interval(CI): 0.377–0. 087) and (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) =0.069, 95% Confidence Interval(CI): 0.062–0.460) respectively.

The attitude toward legalization of abortion among women who attend primary school was 3.666 times (AOR = 3.666, 95% CI: 1.772–7.581) and 3.431 times (AOR = 3.431, 95% CI: 1.083–10.87) more likely compare to those who attended higher education. Again, those who were illiterate and read & write were 4.804 and 11.258 times more likely good attitude than higher education (AOR = 4.804 and 11.26, 95%CI:1.453, 15.881 and 4.49, 28.227) respectively. Knowledge is a factor for attitude toward legalization of abortion. Those who answer, currently abortion on demand is illegal in Ethiopia 77.6% times (AOR = 0.224, 95% CI: .123–.409) less likely had a good attitude than those who answered I don’t know. But those who know abortion on demand is legal in Ethiopia were 1.84 times (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.137–2.976) more likely good attitude than those who don’t know (Table 5 ).

Factors associated with knowledge toward legalization of abortion

All predictors of knowledge toward legalization of abortion were entered into a logistic regression model and the final associated factors were identified. From those entered into the model, marital status, ethnicity and family size were statistically significant for knowledge. The knowledge of women who were Konso, Wolaita and those who were other in ethnicity was 93, 86 and 95.3% less likely more knowledgeable about the legalization of abortion compared to women who were Gamo in ethnicity respectively. The study revealed that single women were about 95.5% times (AOR = .045, 95% CI: .013–0. 158) less likely good knowledge as compared to married women and also the knowledge among divorced were 99.2% times (AOR = 0.008, 95% CI: 0.002–0.040) less likely compared to who married. Similarly, women who have less than 3 and more than 6 children were about 71.5 and 59.6% times (AOR = 0.285, 95% CI: 0.145–0.561) and (AOR = 0.404, 95% CI: 0.174–0.939) less likely had knowledge than those who have 3–6 children respectively (Table 6 ).

The finding of our study showed that knowledge of women toward legalization of abortion was 23.4% which is low. The result was lower than study done in other part of the country. The study from Harari town revealed that about 35.7% of female students have knowledge towards the legislation of abortion. Again, the finding was much lower than the study done in Debra Markos hospital which was 92% [ 1 ]. Also, lower than the study conducted in other countries. The result was lower than study result in South Africa and Armenia which was 32% in South Africa [ 19 ] and 31% of women knew that, abortion is legal under any condition in Armenia [ 13 ]. The possible difference might be the difference in socio economic condition. But, the finding of this study was higher than study done in Zambia and Nepal. In Zambia the result was 16% [ 11 ]. In Nepal, from 1100 rural married women, only 15% knew about abortion law [ 13 ]. These findings clearly showed that the majority of women did not get information on their own affairs. Lack of knowledge is the result of lack of information. The causes of lower knowledge in the study area might be due to poor information dissemination to the target community. The result of systematic review showed that women who have knowledge of the legal status of abortion were less than 50% [ 20 ]. But, a study done in Latvia showed that more than half (53%) of women knew about the legalization of abortion [ 10 , 19 , 21 ]. In contradiction, this result was much higher than study done in Mizan Aman town of Ethiopia which was only 5.7% knew about the legalization of abortion [ 22 ]. This might be due to information dissemination problem throughout the country.

From those women who have good knowledge on the legalization of abortion majorities (84%) and (80%) of them believe it is legal if pregnancy was from rape/incest and from relative respectively. More than half (59%) of women, believes abortion is legal if it has problem on mothers as well as only 13% believe it is legally allowed for the mother if she don’t want.

Concerning the attitude of women; more than half of the respondents had a good attitude toward the abortion legalization while 42% do not. The result was consistent with the study done in the Mizan Aman town in which the attitude of women toward the legalization of abortion was 54.4% [ 22 ]. But, the result was somewhat higher than study done in Armenia and Debra Markos hospital which was 30 and 23% respectively [ 1 , 13 ]. This difference might be due to the reality of the problem in the community. In Ethiopia, act of abortion has condemned almost by all religion and cultures. But, condemnation alone might not bring solution. More than half (57%) of the participants believe if service become legal, women can use the service but, 59% of women don’t think they will use by themselves even if abortion would be legal in Ethiopia. Almost half (53.3%) of respondents don’t think that women would have the right to terminate their pregnancy if the pregnancy fulfills the criteria. Again about 47% do not agree if women decided to terminate their pregnancy in any case. Therefore, the result showed that the majority (56%) of women had a positive attitude toward the legalization of abortion; but still large proportion of women have negative attitude toward the legalization of abortion. This perception of the community shows still need an intervention. In Ethiopia, since 2004 abortion has been legalized under some circumstances. But only less than 6% used public health facilities and about 73% uses private clinics in this finding; the possible reason might be the low knowledge and problem related to the attitude. Changing community knowledge and attitudes might be challenging; particularly when the topic is stigmatized. Additional intervention be needed to improve access to safe abortion service and other reproductive services for women at the community level.

Nearly 40 years after India legalized abortion, Indian women continue to be unaware that safe abortion service was given at public health facilities or was unable to access it. Although abortion has been legal in India for decades, unsafe abortions were estimated to be 90% [ 18 ]. The underlying reason might be the attitude related to the issue. In our case, East Africa, in particular, has one of the world’s highest rates of maternal mortality linked to complications from unsafe abortions. Over 50% of all women seeking abortions in Ethiopia do so outside the reach of trained medical professionals and outside of health facilities even after the legalization of safe abortion service [ 6 ]. The reason might be due to stigma and the wrong belief of the community toward abortion which enforces women to choose secrecy over safety.

In our study, ethnicity, marital status and family size were the socio demographic factors significantly associated with knowledge. For attitude, marital statuses, level of education as well as knowledge were associated factors. The same with the study done in Debra Markos hospital and Mizan Aman town where the knowledge was the associated factors [ 1 , 22 ].This result was in line with the study done in Harari and Zambia; where age, religion and marital status were a factor, but in our study age and religion were not significant [ 11 , 21 ]. But, accessibility to abortion service was a factor for legalization of abortion in Zambia but not in our case [ 11 ]. Again study done in Mizan Aman town, the preference of termination was a factor for the knowledge of abortion; but here in our study it was not an associated factor [ 22 ].

The study showed that educational status, marital status and having knowledge about the legalization of abortion has a statistically significant association with an attitude. The result was in line with the study conducted in Mizan Aman town and Yirgalem south nation nationality of Ethiopia and other parts of Africa [ 11 , 12 , 19 ].

In conclusion, our study indicated that knowledge of women about the legalization of abortion was low and more than half of women had positive attitude to the legalization of abortion. But, still immense proportion of women (42%) have negative attitude toward the legalization of abortion. Moreover, Ethnicity, marital status, and the number of children were strong predictors of knowledge while education, history of pregnancy termination and knowledge were the predictor of attitude toward legalization of abortion. Thus, it was recommended that the concerned body should give attention to awareness creation and give comprehensive health education and information should be given on a local basis.

Adera A, Kassaw MW, Yimam Y, Abera H, Dessie G. Assessment of knowledge , attitude and practice women of reproductive age group towards abortion Care at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2016;3(5 January 2015):618–24.

Google Scholar

Ipas. Facts on Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in Ethiopia. 2010;

Prata N, Holston M, Fraser A, Melkamu Y. Contraceptive use among women seeking repeat abortion in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2013;17(4):56–65.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mekuriaw S, Mesay R, et al. Knowledge , Attitude and Practice towards Safe Abortion among Femalestudents of Mizan-Tepi University, South West Ethiopia. Womens Health Care. 2015;4(6):6–10.

Vekemans M. First trimester abortion guidelines and protocols; Parenthood Federation, International planned; 2005. p. 6–44.

Mesce D, Clifton D. Abortion facts and figures 2011. PRB’s website 2011;5–64.

Otsea K, Benson J, Alemayehu T, Pearson E, Healy J. Testing the safe abortion care model in Ethiopia to monitor service availability , use, and quality. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;115(3):316–21 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.09.003 .

Article Google Scholar

Central Ststistics Agency. Ethiopia demographic and health survey. CSA 2016 p. 46–59.

Wada T. Abortion law in ethiopia : a comparative perspective. Mizan Law Rev. 2008;2(1):24–33.

Melgalve I, Lazdane G, Trapenciere I, Shannoo C, Bracken HWB. Knowledge and attitudes about abortion legislation and abortion methods among abortion clients in Latvia. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2005;10(3):143–50.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cresswell JA, Schroeder R, Dennis M, Onikepe O, Bellington V, Maurice M, et al. Women ’ s knowledge and attitudes surrounding abortion in Zambia : a cross-sectional survey across three provinces. BMJ Open. 2016;6:1–9.

Bitew S, Ketema S, Worku M, Hamu M, Loha E. Knowledge and attitude of women of childbearing age towards the legalization of abortion , Ethiopia. J Sci Innov Res. 2013;2(2):2320–4818.

Chong E, Tsereteli T, Vardanyan S, Avagyan G, Winikoff B. Knowledge atttude and practice of abortion amongwomen and doctors in Armenia. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14(5):348.

World Health Organization(WHO). Safe abortion : http://www.who.int ; second edited. 2012; 6–134.

Benson J, et al. Meetingwomen’s needs for postabortion family planning: framing the questions. Issues in Abortion Care. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1992;2(2). https://www.popline.org/node/325274 .

Muzeyen R, Ayichiluhm M, Manyazewal T. Legal rights to safe abortion : knowledge and attitude of women in north-West Ethiopia toward the current Ethiopian abortion law. Public Health. Elsevier Ltd; 2017;148:129–136. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.03.020

Family health department Federal Democratic of Ethiopia. Technical and Procedural Guidelines for Safe Abortion Services in Ethiopia. web. 2006. p. 12–26.

Namrata S, Sumitra Y. The study of knowledge , attitude and practice of medical abortion in women at a tertiary Centre. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14(12):1–4.

Morroni C, Myer L, Tibazarwa K. Knowledge of the abortion legislation among south African women_ a cross-sectional study. BMC Reprod Health. 2006;3:7 http://www.reproductive-health-journal.com/content .

Assifi AR, Berger B, Tunçalp Ö, Khosla R, Ganatra B. Women ’ s awareness and knowledge of abortion Laws : a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152224.

Geleto A, Markos J. Awareness of female students attending higher educational institutions toward legalization of safe abortion and associated factors , Harari region , eastern Ethiopia : a cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2015;12:1–9.

Mara AM, Ayenew M, Haftu H, Aregay B. Assessment of knowledge and attitudes of men and women aged between 15-49 years towards legalization of induced abortion in Mizan Aman town. J Women's Health Care. 2017;6(3):2167–0420.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to acknowledge our study participants for providing the necessary information and the data collectors for collecting the data carefully.

The data collection process of this study was funded by the Arba Minch University for the support of the data collection. The funding body only followed the process to confirm whether the fund allocated was used for the proposed research.

Availability of data and materials

The data collected for this study can be obtained from the first or last author based on a reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Health, Faculty of public health, Department of Health Economics Management and Policy, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Tilahun Fufa Debela

College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Department of Public Health, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia

Misgun Shewangizaw Mekuria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors involved in the study proposal writing, design, data analysis, write-up, and drafted the first version of the manuscript, and participated in all phases of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Misgun Shewangizaw Mekuria .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

An ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Science of Arbaminch University. Permission letter was obtained from the town health department and was presented to selected households. Oral consent was taken from each participant before the start of data collection. Confidentiality was assured that their responses will not in any way be linked to them. In addition, they were told they have the right not to participate and withdraw from the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is no competing conflict of interest with the presented data as external data collectors collected it. There was no financial interest between the funder and the research area community and the authors. We, the researchers, have no any form of competing for financial and non-financial interest between ourselves.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Debela, T.F., Mekuria, M.S. Knowledge and attitude of women towards the legalization of abortion in the selected town of Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Reprod Health 15 , 190 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0634-0

Download citation

Received : 28 August 2018

Accepted : 28 October 2018

Published : 21 November 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0634-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Legalization

- Women in reproductive age

Reproductive Health

ISSN: 1742-4755

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 April 2024

Reproductive rights in the United States: acquiescence is not a strategy

- Laura J. Esserman 1 &

- Douglas Yee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3387-4009 2

Nature Medicine ( 2024 ) Cite this article

332 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scientific and medical conferences should not be held in states that ban abortion, as such bans put the lives of women at risk.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

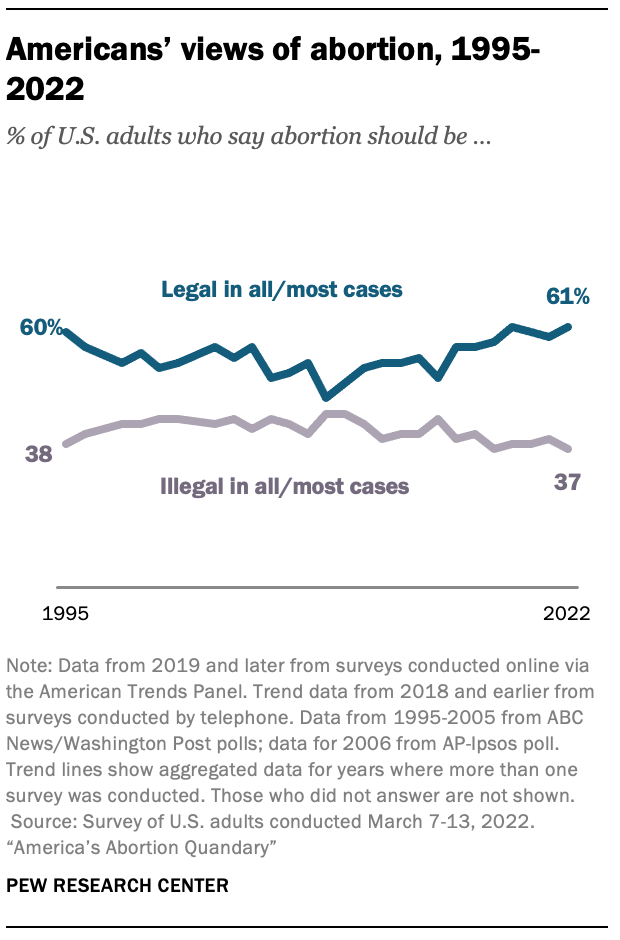

It has been over a year since the US Supreme Court decided that women have no constitutional right to abortion and returned the issue to individual states. Although the majority of US citizens support a woman’s right to decide to terminate a pregnancy, 16 of the 50 US states have now essentially eliminated access to abortion.

As physicians engaged in women’s health, we maintain that abortion is a part of healthcare and that restricting access to abortion further exacerbates healthcare disparities. Bans have a negative impact on women’s health and can lead to lethal complications associated with pregnancy and inappropriate management of failed pregnancy, and risk worse outcomes for health conditions including breast and other cancers 1 .

We, and others 2 , have urged our fellow physicians and scientists not to attend meetings in states that have abortion bans and that subject healthcare providers to criminal prosecution for helping a woman obtain an abortion. We further call on medical societies to refrain from hosting conferences in states that restrict access to reproductive health services and move these conferences to states that fully recognize and support the rights of women and their healthcare providers.