Getting into the right mindset to read scientific papers quickly:

Before you start anything, you need to isolate your singular goal for reading papers in the first place. Otherwise, you’ll be passively reading every paper that comes up rather than hunting for specific details. Don’t be a forager, consuming anything edible that crosses your path. Be a hunter: have a specific target that keeps you selective, efficient, and guides every step you take.

Most of these tips are designed to help you focus on extracting value efficiently so you won’t give up after two papers! So, what is your goal here? Is it:

- Getting a solid foundation in your field?

- Collecting the newest research for a cutting-edge literature review?

- Finding ideas and inspiration to further your own research?

I’ll be honest here: The first dozen papers of a new subject will be a grind. But it gets easier, I promise! When you find yourself blasting through the “template” introduction and recognizing citations you’ve already read, you know you’re close to being an expert. At this point, if you’re struggling to understand a new paper in the field, it’s likely the authors’ fault, not yours.

Keep in mind that academics aren’t exactly known for concise writing. Practice skimming paragraphs for high-value verbs, numerical values and claims. Skip over wordy low-value prose like “We thus appear to have potentially demonstrated a novel and eco-friendly synthesis method for…” It’s easy to fall back to a casual fiction-reading mentality. Try to stay in a high-energy search mode and you’ll be effectively done in half the time.

Later on I’ll reference our journal article notes template , which I used to synthesize notes for my literature review. Go ahead now and open it in Google Drive where you can download and edit it for free. We just ask that you drop your email so that we can stay in touch on new helpful resources and awesome new tools for scientists.

How do you read scientific papers effectively?

Below are my tips for how to read scientific papers most effectively. I used this methodology to write a critical literature review in a brand new field in about 4 months, citing over 150 papers. My first-author paper now has nearly 1000 citations in only six years since publication, making it my advisor’s most highly-cited paper in his 30-year career! You can do this. Just keep reading:

1. Briefly read the Abstract

The abstract is your most condensed look at the paper. Read it quickly and highlight any claims or phrases that you want more details on. I like to copy the entire abstract text or screenshot into the journal article notes template for later reference. It also helps to copy the keyword text into the template or your citation manager tags so you can search for them later. Things to read for:

- Is the research applicable to what you need right now?

- Are the findings significant enough to help you with your goal?

- What is the most interesting aspect of this paper?

2. Carefully read the Conclusion

Reading the conclusion gives you an instant look at the quality of the paper. Do the authors seem to make claims bigger than appropriate for the scope of the paper? Do they use hyperbole to inflate the importance of the work? Are the results not clearly stated? These could be red flags identifying a poor quality paper.

Highlight and copy a few of the most important phrases or sentences out of the conclusion into the journal article template in the first bulleted section or into the notes section of your reference manager. Look for:

- What the authors think they accomplished in this work.

- The reasoning behind their results. Any useful insights?

- Ideas for future experiments.

3. Identify the most important figures and dig through the Results & Discussion for more detail

If you’re still interested after the first two steps, start digging into the results and discussion for more details. Before making the deep dive, write down the specific questions you need to answer in your notes section. Search the paper for those answers, writing down new questions as they come to mind.

One favorite strategy here is to look at each figure, read the caption and then dig through the text for supporting information (use Ctrl+F for “Fig. 3”, for example). The figures should tell the story as well as (and more quickly than) the text.

Copy and paste specific claims you may want to quote or paraphrase later. Isolate what the authors think they did from your own commentary and summarize it in your own words.

4. Search the Methods section to answer questions if necessary

The Methods section is usually the most tedious and tiring to read. That’s why we don’t do it first. Only go through it when necessary or you’ll never get to the 100 other papers you just downloaded.

Go back through the Methods when:

- This paper showed a different result than another similar paper, and the methods may have caused the difference.

- You’re sure you want to include the paper and you want to be critical of the way they conducted their experiments.

- You may want to replicate their experiment in your own work.

Make sure to note anything unique, odd, or unexpected in their methods. Maybe it will lead to a breakthrough in your own work or help explain a surprise result!

5. Summarize your thoughts and critiques

Re-read your notes so far to check for any missed questions. Go back and extract sentences or paragraphs of the paper that you want to challenge so you can quickly find them verbatim. Write your own thoughts and questions around those topics so you can copy them into your literature review later. Ideas for notes:

- What would you have done differently in the experiment or data analysis?

- Is there an obvious gap or follow-up experiment?

- Does this paper uniquely contribute to the field’s body of knowledge? What is its contribution?

6. Copy important figures into your notes

This is the most important step but many don’t do this. Figures are the anchors of every good journal article and the authors who spend the most time making excellent figures also will get cited the most often in review papers. This leads to even more citations from experimental articles. My secret for getting the most citations of my review paper was to spend more time than typical finding or creating the best possible figures for explaining the content. You can do this too, it just takes time!

The best reference manager Zotero doesn’t have an “add image” button in the “Notes” section but you can actually screenshot the image with the Snipping Tool then Ctrl+v paste it into the notes section! Now when you come back to the paper you’ll get an instant look at the most significant figures. If you know you want to use one of these figures in your review, add a tag to the paper like “Figure Rev. Paper 1”.

7. Pick important references (especially review papers) out of the Introduction and Discussion

Now that you have a good understanding of the paper, it’s time to start tidying things up and thinking of where to go next. Skim the introduction for helpful references or check the first 5-10 listed in the References section to find mostly review papers you can use for new leads. Go and download these into an “Unread review papers” folder in your citation manager for when you get stuck later.

Then, go to the journal/library website and check for new papers that have cited this paper. This will help you follow the trail of a specific research topic to see how it’s developing. Download the interesting ones and put them in an “unread” folder for this very specific research topic. In Zotero, you can even tag the paper as “related” to the current paper for quick access later.

8. Clean up the metadata if you plan on citing this paper later

If there’s a chance you’ll cite this paper later, make sure to clean up the metadata so your word processor citation plugin creates a clean reference section. Author initials may be backward, special characters in the title may be corrupted, the year or issue of the journal could be missing or the “type” of citation could be wrong (listed as a book instead of journal article) which would change the format.

Fully tag the paper using whatever system you’ve come up with. Keywords, chemicals, characterization methods or annotation tags like “Best” can all be useful. One other trick I used was to come up with an acronym for the paper I was about to write - “NMOBH” for example - and use that as a tag in any paper that I planned to cite later.

Being methodical in your post-read organization will save you many hours and endless frustration later on. Follow these tips on how to organize your research papers and you’ll be a pro in no time. You’re almost done, but don’t skip this part!

9. Take a break, then repeat!

This methodology makes it a little easier to get through a paper quickly once you get some practice at it. But what about 10 papers? 100?! You can’t do all of your reading in a week. I set a habit for myself over the summer to read two papers a day for 2 months. If I missed a day, I made it up the next day. This keeps you fresh for each paper and less likely to miss important points because you’re falling asleep!

Get comfortable. I preferred to kick back on a couch or outside in a chair using my laptop in tablet mode so I had a long vertical screen and a stylus to highlight or circle things. Reading 2-column scientific articles on a 13 inch 16:9 laptop screen at a desk for hours on end is a special kind of torture that I just couldn’t endure. Change scenery often, try different beverages, take breaks, and move around!

Here are some bonus tips for breaking the monotony between papers:

- Pick your top few most controversial, confusing, or interesting papers and ask a colleague or advisor for their thoughts. Bring them some coffee to discuss it with you for another perspective.

- Email the authors to ask a question or thank them for their contribution. This is a great way to make a connection. Don’t ask for too much on the first email or they may not respond - they are busy!

- Reward yourself for every paper read. Maybe a small snack or a short walk around the block. Physically cross this paper off your to-do list so you internalize the good feeling of the accomplishment!

How do you choose which papers to read next?

So you’re downloading 15 new papers for every 1 paper you read? This could get out of control quickly! How do you keep up? Here are some tips for prioritization:

Google Scholar is an excellent tool for tracking citation trees and metrics that show the “importance” of each paper. Library portals or the journal websites can also be good for this.

- If you’re starting a search on a new topic, begin with a relevant review paper if one exists. Beware of reading too many review papers in a row! You’ll end up with an intimidating pile of citations to track down and it will be difficult to know where to start after a few-day break.

- Prioritize experimental papers with high citation numbers, in journals with high impact factors and by authors with a high h-index (30+) published within the last 5 years. These papers will set the bar for every paper you read after. You can check the journal’s rank in your field by using Scimago .

- Identify the most prominent authors in this field and find their most recent papers that may not have many citations (yet). This indicates where the field is heading and what the top experts are prioritizing.

- After you’ve covered a lot of ground above, start taking more chances on less-established authors who may be taking new approaches or exploring new topics. By now you’ll be well-equipped to identify deficiencies in methods, hyperbolic claims, and arguments that are not well-supported by data.

Final takeaways for how to read a scientific paper:

- Don't be a passive word-for-word reader. Be actively hunting and searching for info.

- Read in this order: Abstract, Conclusion, Figures, Results/Discussion, Methods.

- The figures are the anchors. Save the best ones to reproduce in your article and spend extra time to create your own summary figures to supercharge your chances of citation.

- Clean up the metadata and use a good tagging system to save time later.

- Set your daily goal, reward yourself for finishing, and take breaks to avoid burnout!

Lastly, remember that this blog is sponsored by BioBox Analytics ! BioBox is a data analytics platform designed for scientists and clinicians working with next-generation-sequencing data. Design and run bioinformatic pipelines on demand, generate publication-ready plots, and discover insights using popular public databases. Get on the waitlist and be the first to access a free account at biobox.io !

What sections of a research paper should you read first?

The Abstract and Conclusion sections of a research paper give you a quick sense if you should continue spending time on the paper. Assess the quality of the research and whether the results are significant to your goals. If so, move to the most important Figures and find additional details in the Results and Discussion when necessary.

What is the fastest way to read a research article?

Skim the Abstract and highlight anything of interest. Skip to the Conclusions and do the same. Write questions that pop up. Examine each Figure and find the in-line reference text for further details if needed for understanding. Then search the Results and Discussion for answers to your pre-written questions.

What is the best citation manager software to use for my scientific papers?

I used Mendeley through grad school but recently Zotero seems to be more popular. Both are free and have all the features you need! EndNote is excellent but expensive, and if you lose your institutional license you’ll have a hard time transferring to one of the free offerings. Zotero is your best bet for long-term organizational success!

Also in Life after the PhD - Finishing grad school and what's on the other side

- 11 books to help get you through grad school (in 2024)

11 min read

- 8 PhD Job Interview Questions: What They Ask vs. What They Mean

- 27 ILLEGAL Interview Questions to Know Before Your PhD Job Interview

Recent Articles

- How I negotiated for an extra week (and a half!) of vacation at my first post-PhD research job

- Common pitfalls of PhD thesis writing and 17 tips to avoid them

STEM Gift Lists

Science Gifts Biology Gifts Microbiology Gifts Neuroscience Gifts Geology Gifts Ecology Gifts

Stay up to date

Drop your email to receive new product launches, subscriber-only discounts and helpful new STEM resources.

Gifts for PhD Students, Post-docs & Professors

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …

How to Read Research Papers: A Cheat Sheet for Graduate Students

- August 4, 2022

- PRODUCTIVITY

It is crucial to stay on top of the scientific literature in your field of interest. This will help you shape and guide your experimental plans and keep you informed about what your competitors are working on.

To get the most out of your literature reading time, you need to learn how to read scientific papers efficiently. The problem is that we simply don’t have enough time to read new scientific papers in our results-driven world.

It takes a great deal of time for researchers to learn how to read research papers. Unfortunately, this skill is rarely taught.

I wasted a lot of time reading unnecessary papers in the past since I didn’t have an appropriate workflow to follow. In particular, I needed a way to determine if a paper would interest me before I read it from start to finish.

So, what’s the solution?

This is where I came across the Three-pass method for reading research papers.

Here’s what I’ve learned from using the three pass methods and what tweaks I’ve made to my workflow to make it more personalized.

Build time into your schedule

Before you read anything, you should set aside a set amount of time to read research papers. It will be very hard to read research papers if you do not have a schedule because you will only try to read them for a week or two, and then you will feel frustrated. An organized schedule reduces procrastination significantly.

For example, I take 30-40 minutes each weekday morning to read a research paper I come across.

After you have determined a time “only” to read research papers, you have to have a proper workflow.

Develop a workflow

For example, I follow a customized version of the popular workflow, the “Three-pass method”.

When you are beginning, you may follow the method exactly as described, but as you get more experienced, you can make some changes down the road.

Why you shouldn’t read the entire paper at once?

Oftentimes, the papers you think are so important and that you should read every single word are actually worth only 10 minutes of your time.

Unlike reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper, reading research papers is an entirely different experience. In addition to reading the sections in a different order, you must take notes, read them several times, and probably look up other papers for details.

It may take you a long time to read one paper at first. But that’s okay because you are investing yourself in the process.

However, you’re wasting your time if you don’t have a proper workflow.

Oftentimes, reading a whole paper might not be necessary to get the specific information you need.

The Three-pass concept

The key idea is to read the paper in up to three passes rather than starting at the beginning and plowing through it. With each pass, you accomplish specific goals and build upon the previous one.

The first pass gives you a general idea of the paper. A second pass will allow you to understand the content of the paper, but not its details. A third pass helps you understand the paper more deeply.

The first pass (Maximum: 10 minutes)

The paper is scanned quickly in the first pass to get an overview. Also, you can decide if any more passes are needed. It should take about five to ten minutes to complete this pass.

Carefully read the title, abstract, and introduction

You should be able to tell from the title what the paper is about. In addition, it is a good idea to look at the authors and their affiliations, which may be valuable for various reasons, such as future reference, employment, guidance, and determining the reliability of the research.

The abstract should provide a high-level overview of the paper. You may ask, What are the main goals of the author(s) and what are the high-level results? There are usually some clues in the abstract about the paper’s purpose. You can think of the abstract as a marketing piece.

As you read the introduction, make sure you only focus on the topic sentences, and you can loosely focus on the other content.

What is a topic sentence?

Topic sentences introduce a paragraph by introducing the one topic that will be the focus of that paragraph.

The structure of a paragraph should match the organization of a paper. At the paragraph level, the topic sentence gives the paper’s main idea, just as the thesis statement does at the essay level. After that, the rest of the paragraph supports the topic.

In the beginning, I read the whole paragraph, and it took me more than 30 minutes to complete the first pass. By identifying topic sentences, I have revolutionized my reading game, as I am now only reading the summary of the paragraph, saving me a lot of time during the second and third passes.

Read the section and sub-section headings, but ignore everything else

Regarding methods and discussions, do not attempt to read even topic sentences because you are trying to decide whether this article is useful to you.

Reading the headings and subheadings is the best practice. It allows you to get a feel for the paper without taking up a lot of time.

Read the conclusions

It is standard for good writers to present the foundations of their experiment at the beginning and summarize their findings at the end of their paper.

Therefore, you are well prepared to read and understand the conclusion after reading the abstract and introduction.

Many people overlook the importance of the first pass. In adopting the three-pass method into my workflow, I realized that many papers that I thought had high relevance did not require me to spend more time reading.

Therefore, after the first pass, I can decide not to read it further, saving me a lot of time.

Glance over the references

You can mentally check off the ones you’ve already read.

As you read through the references, you will better understand what has been studied previously in the field of research.

First pass objectives

At the end of the first pass, you should be able to answer these questions:

- What is the category of this paper? Is it an analytical paper? Is it only an “introductory” paper? (if this is the case, probably, you might not want to read further, but it depends on the information you are after)or is it an argumentative research paper?

- Does the context of the paper serve the purpose for what you are looking for? If not, this paper might not be worth passing on to the second stage of this method.

- Does the basic logic of the paper seem to be valid? How do you comment on the correctness of the paper?

- What is the main output of the paper, or is there output at all?

- Is the paper well written? How do you comment on the clarity of the paper?

After the first pass, you should have a good idea whether you want to continue reading the research paper.

Maybe the paper doesn’t interest you, you don’t understand the area enough, or the authors make an incorrect assumption.

In the first pass, you should be able to identify papers that are not related to your area of research but may be useful someday.

You can store your paper with relevant tags in your reference manager, as discussed in the previous blog post in the Bulletproof Literature Management System series.

This is the third post of the four-part blog series: The Bulletproof Literature Management System . Follow the links below to read the other posts in the series:

- How to How to find Research Papers

- How to Manage Research Papers

- How to Read Research Papers (You are here)

- How to Organize Research Papers

The second pass (Maximum: 60 minutes)

You are now ready to make a second pass through the paper if you decide it is worth reading more.

You should now begin taking some high-level notes because there will be words and ideas that are unfamiliar to you.

Most reference managers come with an in-built PDF reader. In this case, taking notes and highlighting notes in the built-in pdf reader is the best practice. This method will prevent you from losing your notes and allow you to revise them easily.

Don’t be discouraged by everything that does not make sense. You can just mark it and move on. It is recommended that you only spend about an hour working on the paper in the second pass.

In the second pass:

- Start with the abstract, skim through the introduction, and give the methods section a thorough look.

- Make sure you pay close attention to the figures, diagrams, and other illustrations on the paper. By just looking at the captions of the figures and tables in a well-written paper, you can grasp 90 percent of the information.

- It is important to pay attention to the overall methodology . There is a lot of detail in the methods section. At this point, you do not need to examine every part.

- Read the results and discussion sections to better understand the key findings.

- Make sure you mark the relevant references in the paper so you can find them later.

Objectives of the second pass

You should be able to understand the paper’s content. Sometimes, it may be okay if you cannot comprehend some details. However, you should now be able to see the main idea of the paper. Otherwise, it might be better to rest and go through the second pass without entering the third.

This is a good time to summarize the paper. During your reading, make sure to make notes.

After the second pass, you can:

- Return to the paper later(If you did not understand the basic idea of the paper)

- Move onto the thirst pass.

The third pass (Maximum: four hours)

You should go to the third stage (the third pass) for a complete understanding of the paper. It may take you a few hours this time to read the paper. However, you may want to avoid reading a single paper for longer than four hours, even at the third pass.

A great deal of attention to detail is required for this pass. Every statement should be challenged, and every assumption should be identified.

By the third pass, you will be able to summarize the paper so that not only do you understand the content, but you can also comment on limitations and potential future developments.

Color coding when reading research papers

Highlighting is one way I help myself learn the material when I read research papers. It is especially helpful to highlight an article when you return to it later.

Therefore, I use different colors for different segments. To manage my references, I use Zotero. There is an inbuilt PDF reader in Zotero. I use the highlighting colors offered by this software. The most important thing is the concept or phrase I want to color code, not the color itself.

Here is my color coding system.

- Problem statement: Violet

- Questions to ask: Red (I highlight in red where I want additional questions to be asked or if I am unfamiliar with the concept)

- Conclusions: Green (in the discussion section, authors draw conclusions based on their data. I prefer to highlight these in the discussion section rather than in the conclusion section since I can easily locate the evidence there)

- Keywords: Blue

- General highlights and notes: Yellow

Minimize distractions

Even though I’m not a morning person, I forced myself to read papers in the morning just to get rid of distractions. In order to follow through with this process (at least when you are starting out), you must have minimum to no distractions because research papers contain a great deal of highly packed information.

It doesn’t mean you can’t have fun doing it, though. Make a cup of coffee and enjoy reading!

Images courtesy : Online working vector created by storyset – www.freepik.com

Aruna Kumarasiri

Founder at Proactive Grad, Materials Engineer, Researcher, and turned author. In 2019, he started his professional carrier as a materials engineer with the continuation of his research studies. His exposure to both academic and industrial worlds has provided many opportunities for him to give back to young professionals.

Did You Enjoy This?

Then consider getting the ProactiveGrad newsletter. It's a collection of useful ideas, fresh links, and high-spirited shenanigans delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

I accept the Privacy Policy

Hand-picked related articles

Why do graduate students struggle to establish a productive morning routine? And how to handle it?

- March 17, 2024

How to stick to a schedule as a graduate student?

- October 10, 2023

The best note-taking apps for graduate students: How to choose the right note-taking app

- September 20, 2022

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Post Comment

FounderScholar

- Kevin’s List (Invite Only)

How to Read Like a Doctoral Student

In his wildly popular 1986 book, All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten , author Robert Fulghum reminds readers of simple lessons they once learned but may have forgotten, lessons such as share everything, wash your hands before you eat, and of course, flush. During the past year, I’ve experienced the opposite of what Fulghum describes. Some things I’ve done my entire post-kindergarten life—that I thought I was pretty good at—I’ve had to relearn.

Things like reading and writing.

You see, I’ve just recently finished the first year of a business doctorate and the program forced me to revisit reading and writing skills I’ve always taken for granted.

In a recent twitter thread, I described my admittedly still brief experience in the program:

1/ Coming from industry to work on a business doctorate, many friends ask first, "Why the hell would you do something like that?" Then, they follow with, "So what do you do in a doctorate?" #phdchat — Kevin P. Taylor (@ktaylor) May 30, 2018

When friends, family, and people in my industry hear that I am pursuing a doctorate in my forties after a career in technology and entrepreneurship, they fall into one of two camps.

Firstly, there are the people who subconsciously savor the sight of a train wreck. These are the people who slow down and lean over to get a better view when passing a three-car pileup on the highway.

From these dear friends and relatives, I hear comments such as, “Wow, kudos to you but I’m so done with school. No way! So, what does it involve, anyway?”

When I tell the second group of friends and family about my educational plans and the “interesting” research projects I am pursuing, I’ll catch a sparkle in eye.

From these folks, I hear comments like, “I would love to do that someday. I almost applied to a Ph.D. program after undergrad but, you know, I had student loans to pay off. So, what does it involve, anyway?”

The short answer is reading, reading, and more reading.

In this blog post, I’ll share five techniques I’ve learned over the past year while learning how to read as a doctoral student, where I’m required to read, retain, and recall large amounts of complex information.

If you must absorb and make use of large quantities of information (everyone?), then you too will benefit from learning the powerful—but not easy—reading techniques that follow.

This is not the reading you learned in kindergarten.

5 Advanced Techniques to Learn How to Read More Effectively

In the past month, I’ve read 575 pages from scientific journals and academic book chapters in electronic format (either a PDF or a Kindle book). I’ve read several hundred additional pages in paper books.

This is a normal reading load in my program.

The reading doesn’t always go smoothly. Many time over the past year—usually after 10-12 hours of binge reading—my eyes would quiver and water.

At one point I could no longer focus my eyeballs on words. Imagine that feeling when trying to do your…let’s imagine…50th push-up but your arms just stop taking orders from your brain.

So, how do doctoral students read so much dense material and keep it all straight? Scientific articles are not reading cliffhangers. No Harry Potter or The Hunger Games 1 for doctoral students.

And, just as important, how do doctoral students retain and recall everything we’ve read?

During the first few months of my doctoral studies, it was clear I was coming into the program ill-equipped for the amount and type of reading that was expected. The techniques that follows are what I found work best for me. 2

Read with a Purpose in Mind

Do you read novels at work?

Probably not, if you’re like most people. You have job to do, for crying out loud. But, when you read like a doctoral student, reading is your job. You must treat it as such.

Keeping that in mind, every time I crack open a book or journal article, I do so with a clear purpose in mind.

I read to accomplish a predefined goal. When done, I don’t linger in the material, I move on. If you don’t take anything else away from this article, remember to read for a specific purpose.

Let’s look at some reasons I might need to read something. Depending on your job, you may come up with a different list.

Purpose for Reading

- When I start a new research topic, I likely don’t know much about it. I won’t be sure what research questions 3 to ask. What has already been discussed and researched? Who is writing and working in the area? When doing this type of survey-level reading, I stay at 30,000 feet. My goal is to understand terminology, categorization, schools of thought, common research methods, seminal works, and prolific authors.

- The world evolves over time and scientific knowledge is no exception. The state-of-the-art knowledge a year ago could now be refuted, retracted, or otherwise out-of-favor. Assuming I’ve developed a specific research question on a topic and understand the area broadly, I’ll want to delve into the specifics—detailed information on hypotheses, constructs, phenomena, models, methods, and theories.

- If I have a general understanding of a topic and know the current state of knowledge, I’ll want to learn what gaps exist in the current knowledge about a topic (e.g. the effect of passion on launching new ventures). If I have a specific question in mind, has it already been answered? If it has, am I convinced the answer is plausible? Or, are there reasons to doubt (e.g. are currently accepted conclusions built on shaky research or are the conclusions over-generalized)? If my research question hasn’t been answered yet, this could point to a possible research opportunity.

- Sometimes I need to acquire a new skill. For instance, I may need to test the reliability of a set of survey questions or I may need to perform a statistical analysis that I haven’t used before. In what ways have previous researchers already done the same things? (Precedent is important in science.)

Your method of reading should be driven by its purpose. To gather the right level of information with the least time investment, I read in layers.

Read in Layers

Imagine a journal article or academic book is an onion. Both consist of layers of material. And, both can make you cry.

Thinking of reading material as a series of layers to be peeled focuses my time and energy on only the layer that will best serve my purpose at that moment.

Layer One Scanning

The first layer of a piece is its outer shell. Layer one scanning reveals the most basic information. I use that information to decide if it is relevant to my purposes.

The output of layer one scanning is simply a list of relevant pieces I will later read for layer two survey-level information.

For a journal article, 4 the first layer is comprised of just the title and abstract.

Together the title and abstract should contain enough information to decide if the article warrants closer examination.

The first layer of a book includes its title, cover material, table of contents, and any relevant book reviews.

If I believe a piece could be useful to my research, I move it to a second layer reading to understand its background, conclusions, and key points.

Layer Two Reading

Layer two reading is the scientific equivalent of CliffNotes™.

The second layer of a journal article is comprised of the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, also known as the AIC . In layer two reading, I quickly read the abstract, introduction and conclusion and lightly skim the method and analysis sections and all tables and figures.

A book’s second layer consists of its preface, introduction, table of contents, chapter introductions and conclusions, and, again, any figures and tables. In addition, I skim the body of each relevant chapter looking for important nuggets. This will give me a fair approximation of a book’s contents with only a few hours investment.

Layer Three Reading

The third layer of a piece represents its nitty-gritty details.

A third layer reading is a full, detailed examination of the entire piece (article or book). At this level of reading, I engage deeply with the material, reading it front to back, closely examining every figure and table, every claim or finding, every step of its narrative.

Clearly, I reserve third layer reading to pieces that are highly relevant to my topic of interest.

While reading each progressive layer of material, I highlight and annotate. In other words, I engage the author in a conversation via the margins of the piece.

Converse with the Author

Active learning increases information retention and recall. In fact, systems such as the SQ3R Method provide a well-trodden approach to active reading.

My version of active reading includes reading in layers (action) and conversing with the author (another action) at increasing levels of detail. Conversing with the author requires both systematically highlighting text and scribbling comments in the margins.

The deeper I read, the more I converse. The conversation should heat up as I develop a more nuanced view of the piece.

Highlight and Annotate

When I read in layer two, focusing on the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, I highlight the most important points in yellow, usually less than one sentence per paragraph. Orange highlighting designates supporting points, while sky blue marks any references I need to further examine.

In addition to structured highlighting, I write brief notes in the margins, questions, cross-references, etc. I specifically annotate the following:

- Purpose of the piece,

- Gaps addresses,

- Gaps not addressed,

- Sketch out the theoretical model,

- Hypotheses,

- Sample and methods used (survey, experiment, etc.),

- Findings, and

- Obvious inconsistencies, questions, or cross references to related material.

Make Up Your Own Shorthand

I use my own homemade shorthand:

- “RI” is for a research idea,

- “Q” is for a question,

- Empty Square is a to-do item (i.e. a checkbox),

- “Gap” identifies a gap in the literature,

- “RQ” is the piece’s research question.

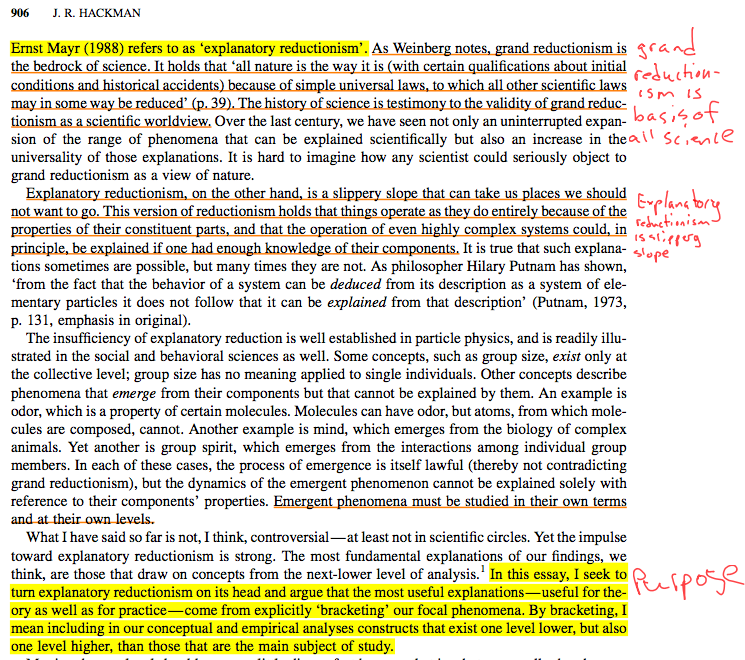

Here is an example of an article I recently read at layer three for a research methods class:

Consume instead of Preserve

If you are anything like me, you love books. You probably have stacks of books sitting near your chair as you read this. Like me, you might even have some in protective covers.

But when I read to learn, I consume my material. I destroy books and journal articles with highlighters and red pens.

Yes, deface, mutilate.

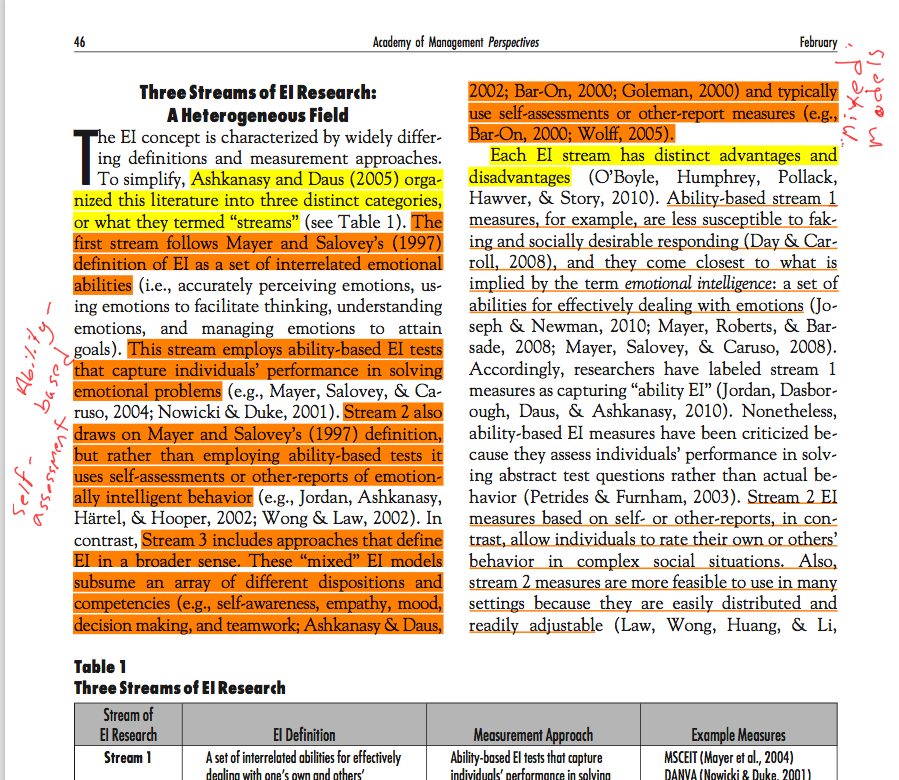

Here’s a recently defaced PDF:

I should be clear, though. I only deface books in electronic format or books still in print that I can easily replaced.

If a book is out-of-print or borrowed (e.g. from a library), I never mark in it but instead use plenty of sticky notes.

The point is that purposeful reading of a book or article is important work. Work often requires consuming resources.

The book or journal article is there to serve my purpose.

Summarize and Synthesize the Material

After spending time reading, highlighting and annotating an article or book, it is time to put the new information in context and make sure it is available for future recall.

Unlike the ancients and their method of loci 5 people today are not trained to retain and recall vast quantities of detailed information using memory alone.

Instead of trying to remember everything using my sketchy-at-best memory, I use a structured process of summarizing and synthesizing new information. How in-depth I do this depends on the reading layer in which I’m operating.

During layer one reading I’m simply trying to collect and organize relevant sources for later use. During my searches, if a piece looks interesting based on its title and abstract, I simply import the reference into Zotero 6 7 , my citation management software.

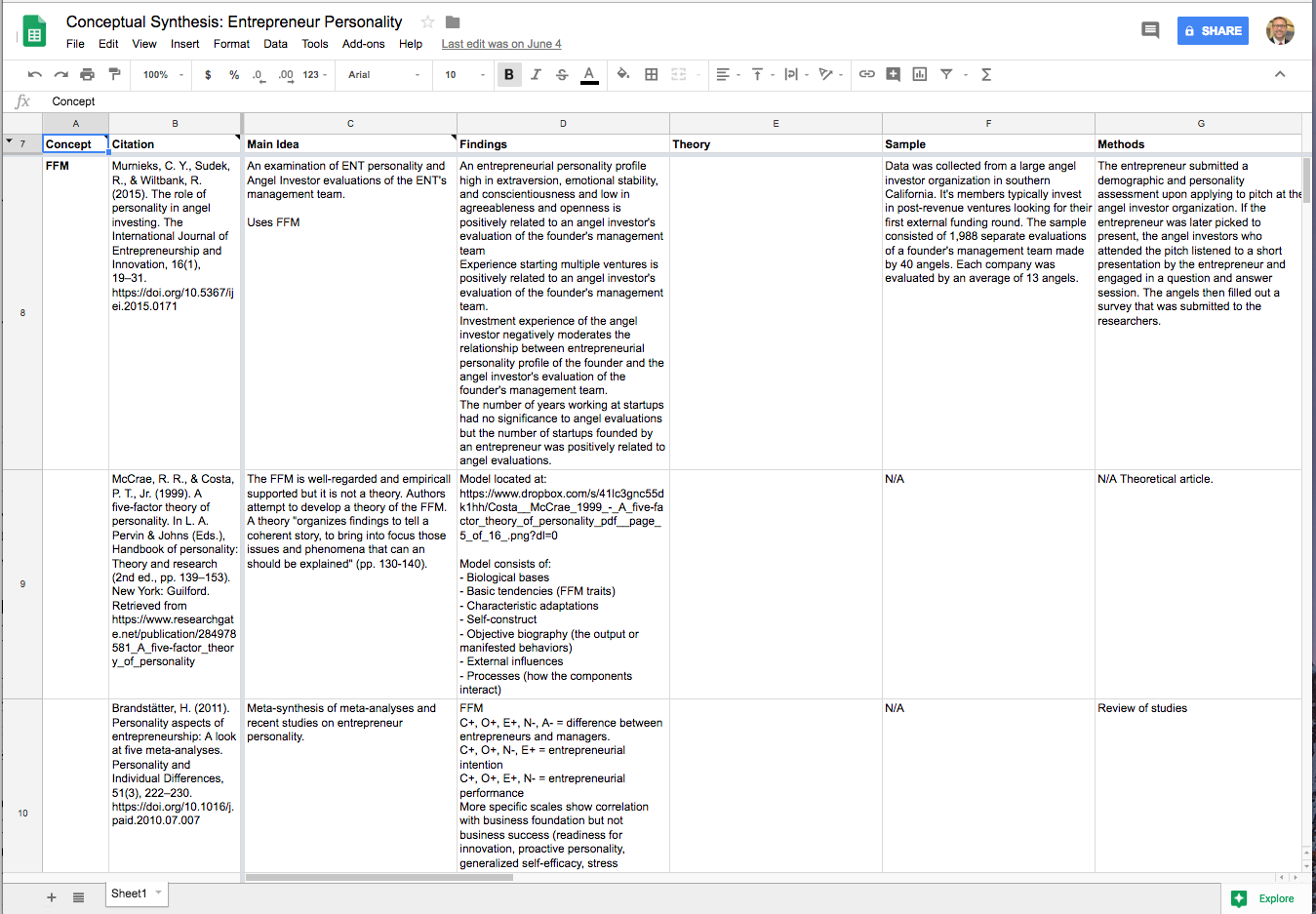

After a layer two reading, I will have highlighted and annotated the most important parts of the book or article. Immediately after reading—or better, while reading—I put notes into a structured Google Sheet called a “conceptual synthesis worksheet.”

I create one conceptual synthesis worksheet for each important keyword or concept in my research topic. These worksheets also correspond to the subfolders in my Zotero citation management software. For example, a current project has worksheets and Zotero subfolders for the following topics: Entrepreneur Personality, Angel Decision-Making, Angel Motivation, and Angel Investor Characteristics.

After layer two reading, in addition to populating a row in a conceptual synthesis worksheet, I often write (meaning sometimes write) a prose summary and synthesis of the piece in a structured “Journal Reading Summary Form.” In the JRSF, I address the following questions:

- What is the aim of the research? Specifically, what “big picture” practical question is highlighted and what more focused research question is addressed?

- Why should anyone care?

- What major theory(ies) are used to support the work?

- What methods are used to test the study’s hypotheses or research questions?

- What are the major findings/conclusions?

- What are the most important contributions of the research?

Early in my doctoral program, a professor handed out these questions to the class. But, there are several “how to read a journal article” documents floating around the Internet with similarly structured note-taking forms.

Layer three reading helps develop a deep understanding of a piece. In my experience, this only occurs after attempting to synthesizing the material with other research I’ve read and with my own thoughts.

Layer Three

Synthesizing material during level three reading requires developing an understanding of how the piece relates to the work of others and the work that I am doing. This is where I really question the material, think critically. Question everything: assumptions, methods, sample, validity, and reliability. Where are the contradictions? Do the conclusions make sense in the real world? What are the flaws (all research is flawed) and how could those flaws be overcome in future research?

I use one of two ways to synthesize material during layer three reading (deep reading). If a piece is not immediately needed, I write a stand-alone memorandum and store it in Zotero.

If I need the synthesis for a current project, I might also create a shortened version of the memorandum and include it in the project’s annotated bibliography , if it exists. In any case, I also save the AB entry in Zotero for future use.

Go Read Like a Doctoral Student

Whether you are a doctoral student, an entrepreneur, or engage in other knowledge work, the skills to efficiently filter through large amounts of information and purposefully capture and use just what you need can be a competitive advantage.

For example, I follow over a thousand blogs in my Feedly account . I check my account once a week or so and there are always hundreds of new posts.

I use similar techniques to what we’ve explored in this article to quickly scan at layer one, survey-level read at layer two and, rarely, dive deep at layer three. Blog posts and web pages that pass my layer one scan go into an Instapaper folder until I have time to read it at layer two.

My challenge to you today is, think about what we’ve discussed in this article. How can you use these techniques to stop reading…all…the…words…in a book or article and just read to accomplish your specific purpose?

What information organization system can you set up this week using Zotero, Evernote, Feedly, Instapaper, Google Drive, etc. to organize and manage the information you consume and want to recall?

Robert Fulghum, the author of All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten shared many useful lessons from kindergarten. But, even he assumed reading was a given. But reading at an advanced level, for a purpose, takes a systematic approach. Now you have the necessary tools to do just that.

Share this post:

- Well, unless you happen to be a scholar researching Harry Potter or The Hunger Games .

- The techniques are not my invention and have been shamelessly borrowed from other smart people.

- Good research questions are ones that investigate something interesting, that are valuable either practically or theoretically, and that can possibly be answered given the researcher’s resources, time frame, and skill set.

- Journal articles follow consistent formats. Quantitative articles often contain an abstract, introduction, method, analysis, discussion, and conclusion section.

- Also know as memory palaces.

- Zotero has a powerful “Connector,” or browser plugin, that makes it easy to import sources directly from web pages and library databases.

- Each of my writing projects might use 5-8 Zotero subfolders to organize the material. You could alternatively use another citation database, or even Evernote , Google Drive , or Dropbox for organization.

Related Articles

Sign up to explore the intersection of evidence-based knowledge and hands-on startup experience..

Several times a month you’ll receive an article with practical insight and guidance on launching and growing your business. In addition, you’ll be exposed to interesting, influential or useful research, framed for those in the startup community.

Thanks a lot for this article, so helpful as a new PhD candidate. I especially liked the Layer reading method and conceptual synthesis worksheet.

Thanks, Sarah — good luck with your PhD.

This is really a helpful article,I have gotten a couple of nuggets from it,I plan to use them during my researches.Glad I stumbled on this article.

Really helpful article. I know I am replying multiple years later, but I have a question. How do you do all this and still read multiple journal articles? It takes me several hours just to finish a single article by reading through, so I can barely get to the next article I have to read. What enabled you to do all of this layered reading and writing for one paper that you read and still be able to read other papers without it taking millenia?

Scott, thanks for the questions. In short, the point of the layers is to save myself time. I only read papers at layer 2 if layer 1 indicated it is relevant to my project. If not, I’ve just saved myself a lot of time. Layer 3 papers are the ones I spend the most time with but those are the most important papers and deserve the time.

If you are taking several hours to read each paper, let me reassure you that it will get faster, especially if you use a triage system like the one I describe here. As you get to know a particular literature well, you will skim much of the front end of a paper because it’s repeating what you already know. You’ll be looking for the results and any anomalies or issues with the methods.

Good luck in your journey.

Wow I read this and got inspired, I did not feel anxious about the idea of reading until my eyes hurt or felt some discomfort. Wonderful writing! This is an article most PhD students need to see.

Thank you for this information. The conceptual synthesis worksheet will be very helpful to current and future research and assignments.

You’re welcome!

Kevin- This is awesome and incisive work. Love the practicality. Well Done!

Thanks for reading!

Glad you enjoyed the post. Thanks for the recommendation for “Digital Paper.” I’m eager to learn more techniques. I’ve read the skimming, scanning, extracting terminology the book description mentions but it looks like it is more extensive than what I’ve seen previously. I’ll check it out.

Great writeup Kevin!

I wanted to pass on a related reading, “Digital Paper” by Andrew Abbott (Sociology prof @UChicago), which is about the art of scholarly library research. He has 7 stages (“design, search, scanning/browsing, reading, analyzing, filing, and writing”), which has some similarities to how you outlined your process in this post.

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo18508006.html

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 07 July 2022

How to find, read and organize papers

- Maya Gosztyla 0

Maya Gosztyla is a PhD student in biomedical sciences at the University of California, San Diego.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

“I’ll read that later,” I told myself as I added yet another paper to my 100+ open browser tabs.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01878-7

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Research management

Londoners see what a scientist looks like up close in 50 photographs

Career News 18 APR 24

Deadly diseases and inflatable suits: how I found my niche in virology research

Spotlight 17 APR 24

How young people benefit from Swiss apprenticeships

Researchers want a ‘nutrition label’ for academic-paper facts

Nature Index 17 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

I dive for fish in the longest freshwater lake in the world

Female academics need more support — in China as elsewhere

Correspondence 16 APR 24

Postdoctoral Position

We are seeking highly motivated and skilled candidates for postdoctoral fellow positions

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston Children's Hospital (BCH)

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Head of the Thrust of Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Reporting to the Dean of Systems Hub, the Head of ROAS is an executive assuming overall responsibility for the academic, student, human resources...

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

BeiGene Ltd.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Doctoral Student Guide

- Kemp Library Video Tutorials

- Advanced Search Techniques

- Tools for Educators

- D.H.Sc. Resources

- Database Video Tutorials

- Online/Electronic Resources

- Google Scholar

- Peer Reviewed

- How to confirm and cite peer review

- What are...

- Action Research

- ESU Off Campus Log In

- Primary/Secondary Sources

- Legal Research Resources

- Evidence Based Practice/Appraisal Resources

- Apps You Didn't Know You Needed

- Internet Searching

- Online Learning Study Tips

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Reviews

- Thesis Guide

- Who is citing me?

- Dissertation/Thesis Resources

- Citations APA

- Journal Impact Factors

- Class Pages

- We Don't Have It? / Interlibrary Loan

- Questions After Hours

This page contains resources on how to be a better reader (for specific help on reading journal articles look under the Find Articles tab). It also includes various ideas on note-taking, and ideas and strategies for studying. There are written articles/editorials and videos. Resources are listed in no particular order.

Please review for what works best for you. If you have a method that you find works better for you that is not here, please let me know so I can include it!

Need help with writing? Try these resources from the University of North Carolina.

- Videos on reading

- Note-Taking

- Videos on Note-taking

- Videos on studying

- Aimed more towards for-fun reading, but has some good advice

- Again towards for-fun reading, but has tons of additional links and good advice.

- How to improve reading comprehension advice

- Reading a textbook quickly and effectively

There are a bunch of videos in the next tabs that discuss a variety of different types of reading strategies - how to read faster, how to read a textbook, how to increase reading comprehension, etc.

- Taking notes while reading from the University of North Carolina

- 5 Effective Note Taking strategies from Oxford Learning.com

- 5 Note Strategies, with written and video explanations. And Street Fighter characters to illustrate.

- Not techniques so much as practical advice

- 36 Examples and Free Templates on the Cornell Method

- Blank note taking templates

- LifeHack notetaking tips

- The complete study guide for every type of learner - explains different kinds of learners and what study methods might work best for you based on how you learn information best

- Studying 101: Study Smarter Not Harder : from the University of North Carolina

- Studying Guide from Oregon State University

- << Previous: Internet Searching

- Next: Online Learning Study Tips >>

- Last Updated: Feb 15, 2024 1:25 PM

- URL: https://esu.libguides.com/doc

- How to Read a Journal Article

- Doing a PhD

As a PhD student (and anyone involved in research) you’ll be reading a lot of journal articles; you’ll come across of hundreds of papers, some of which will be very relevant to your research and others that won’t be. So how do you approach the art of paper reading to ensure you’re efficient and also that you get the most from them? Well, there are many ways! Some academics prefer to go from start to finish, taking in each word, whilst others have a strategy of reading specific sections first. We prefer the latter – here are a few tips from us to try out:

We suggest using a three-pass strategy where you take in more detail on each pass and decide at each stage if there’s enough there for you to spend more time on.

1. Pass One

Use your first view of the paper to get a quick feel of what the papers about. This is a max 10-minute task after which you decide if you need to spend any more time on this paper. We suggest:

1. Read the title, abstract and the aims/objectives, usually found at the end of the introduction

2. Read through the headings used throughout the paper (but not the content under them at this stage)

3. Read the conclusions

After this first glance over the paper, you should (1) have an idea of what type of paper this is (e.g. experimental study, the development of a new method etc.), (2) the main things that the authors did and (3) what the take-home messages were. You should also be able to tell at this stage how well the paper is written. From the information gleaned from the first pass, it’s up to you now if there’s enough interest from you to give it a second more detailed read or if this paper doesn’t interest you or it’s too difficult to understand.

2. Pass Two

If you decide to spend more time on the paper, this second pass is the time to take in the paper’s content. Go through the methodology in detail – does it make sense? Is this how you would do things? What results are presented? Graphs, figures, tables? Do they make sense? Have the appropriate statistical analysis methods been applied? You should be able to summarise and explain what this paper’s about to someone else after this pass.

3. Pass Three

This final pass is an opportunity to think about how the paper fits in the context of your research. Have the authors presented new data or knowledge that could affect or change the direction of your work? Have they identified or presented new gaps in knowledge that you could address in your research? Equally important here is to make sure you’re clear on the limitations of the study and what assumptions the authors have made. Thinking about the methodology, would you be able to recreate the results? Would you be happy making the same assumptions or would you do things differently?

As the last point – think about these same steps when you’re writing your own papers !

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

LET US HELP

Welcome to Capella

Select your program and we'll help guide you through important information as you prepare for the application process.

FIND YOUR PROGRAM

Connect with us

A team of dedicated enrollment counselors is standing by, ready to answer your questions and help you get started.

- Capella University Blog

- PhD/Doctorate

5 must-reads for doctoral students

January 11, 2016

The decision to pursue a doctoral degree can be exciting and scary at the same time.

Good preparation will ease the path to writing a great dissertation. Reading some expert guide books will expand your knowledge and pave the way for the rigorous work ahead.

Capella University faculty, doctoral students, and alumni recommend these five books for doctoral students in any discipline.

1. How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading by Mortimer J. Adler

âOne book fundamental to my doctoral education that my mentor had my entire cohort read, and which I still recommend to this day, is How To Read a Book , which discusses different reading practices and different strategies for processing and retaining information from a variety of texts.â â Michael Franklin, PhD, Senior Dissertation Advisor, Capella School of Public Service and Education.

Originally published in 1940, and with half a million copies in print, How to Read a Book is the most successful guide to reading comprehension and a Capella favorite. The book introduces the various levels of reading and how to achieve themâincluding elementary reading, systematic skimming, inspectional reading, and speed-reading.

Adler also includes instructions on different techniques that work best for reading particular genres, such as practical books, imaginative literature, plays, poetry, history, science and mathematics, philosophy, and social science works.

2. Dissertations and Theses from Start to Finish by John D. Cone, PhD and Sharon L. Foster, PhD

This book discusses the practical, logistical, and emotional stages of research and writing. The authors encourage students to dive deeper into defining topics, selecting faculty advisers, scheduling time to accommodate the project, and conducting research.

In clear language, the authors offer their advice, answer questions, and break down the overwhelming task of long-form writing into a series of steps.

3. Writing Your Dissertation in 15 Minutes a Day by Joan Balker

This book is recommended for its tips on compartmentalizing a large project into actionable items, which can be helpful when working on a project as mammoth as a dissertation. Balker connects with the failure and frustration of writing (as she failed her first attempt at her doctorate), and gives encouragement to students who encounter the fear of a blank page.

She reminds dissertation writers that there are many people who face the same writing struggles and offers strong, practical advice to every graduate student. Writing Your Dissertation in 15 Minutes a Day can be applied to any stage of the writing process.

4. From Topic to Defense: Writing a Quality Social Science Dissertation in 18 Months or Less by Ayn Embar-Seddon OâReilly, Michael K Golebiewski, and Ellen Peterson Mink

As the authors of this book state, âEarning a doctorate degree requires commitment, perseverance, and personal sacrificeâplacing some things in our lives on hold. It is, by no means, easyâand there really is nothing that can make it âeasy.ââ

This book provides support for the most common stumbling blocks students encounter on their road to finishing a dissertation. With a focus on a quick turnaround time for dissertations, this book also outlines the importance of preparation and is a good fit for any graduate student looking for support and guidance during his or her dissertation process.

From Topic to Defense can be used to prepare for the challenges of starting a doctoral program with helpful tools for time management, structure, and diagnostics.

5. What the Most Successful People Do Before Breakfast: A Short Guide to Making Over Your Morningsâand Life by Laura Vanderkam

According to author and time management expert Laura Vanderkam, mornings are key to taking control of schedules, and if used wisely, can be the foundation for habits that allow for happier, more productive lives.

This practical guide will inspire doctoral students to rethink morning routines and jump-start the day before itâs even begun. Vanderkam draws on real-life anecdotes and research to show how the early hours of the day are so important.

Pursuing a doctoral degree is a big decision and long journey, but it also can be an exciting and positive experience. Learn more about Capellaâs online doctoral programs .

What's it like to be a doctoral student?

Learn more about the experience, explore each step of the journey, and read stories from students who have successfully earned their doctorate.

Explore The Doctoral Journey >>

You may also like

Can I transfer credits into a doctoral program?

January 8, 2020

What are the steps in writing a dissertation?

December 11, 2019

The difference between a dissertation and doctoral capstone

November 25, 2019

Start learning today

Get started on your journey now by connecting with an enrollment counselor. See how Capella may be a good fit for you, and start the application process.

Please Exit Private Browsing Mode

Your internet browser is in private browsing mode. Please turn off private browsing mode if you wish to use this site.

Are you sure you want to cancel?

Adventures of a PhD candidate

Reflections on the thesis journey

The way I take notes for my PhD

In high school I was really bad at taking notes and studying. So much so that I barely got into a university degree! In my undergraduate I slowly learnt tricks for studying and remembering all the things I had to do. But when you begin a PhD, it is quite honestly a whole new ball game. The things you read you will need to be able to find, and remember in two or three years time!

Everybody has a different process, but I thought I would outline mine in this blog post. I’ll begin with a confession; the thought of PDFs in folders has always scared me. To me, the idea of knowing what a file is by the way I name it and being able to find the things I have highlighted a year later seemed (and still seems) impossible. I honestly do not know how people just use PDFs on their computer to remember all of the things they have read (hats off to those who can do that!). In the beginning of my PhD I printed every article I read, so I could file it manually ( my inspiration here ). I still think this is the best method for me, but I have had to adapt it due to overseas fieldwork (can’t exactly drag printed articles around the world with me).

Below I detail the steps I take when reading an article/book/whatever for my PhD.

Manually enter the article into EndNote

I know some (most?) PhD students import database searches into their EndNote libraries and work from there. But I have two issues from this:

- You have to check the references to ensure authors don’t have different name versions (otherwise in documents your EndNote will automatically treat them like two authors who have the same last name and first initial).

- How do you know what you have read? Or where to start reading?

I manually enter the details to avoid this. In the beginning I used the EndNote keyword feature to help find articles I had entered, but now I do not do this (as I use Nvivo and it is easier to find things and it is a bit redundant with the way I file articles). In my endnote I simply add all necessary bibliographical information and attach the PDF (my back up in case of catastrophic tech failure). I also use the endnote online to sync my library to the cloud.

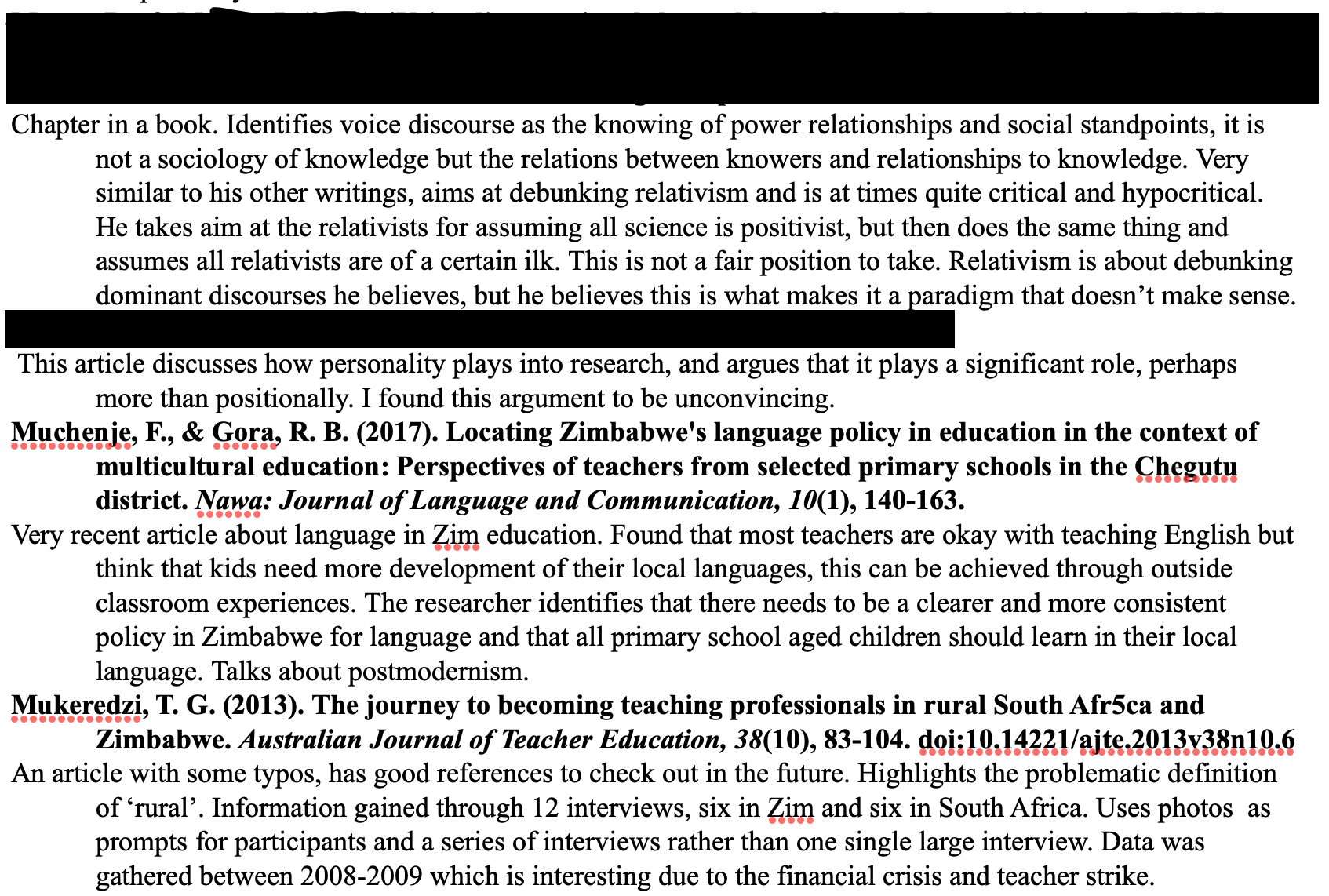

Add an annotated bibliography entry to my scrivener

This annotated bibliography is whatever I am thinking/feeling at the time. Some entries are more detailed than others. See the example below:

I have blocked the first two entries APA reference as I am quite critical in my entry of them (not quite ready to have such a strong academic voice just yet). You will notice how all four of the entries are quite different with what they identify and talk about. I don’t follow a set pattern for these, it is quite literally my thoughts. For most it is a summary of what the article said and my thoughts. This is a good way to begin to think critically about all of the things you read.

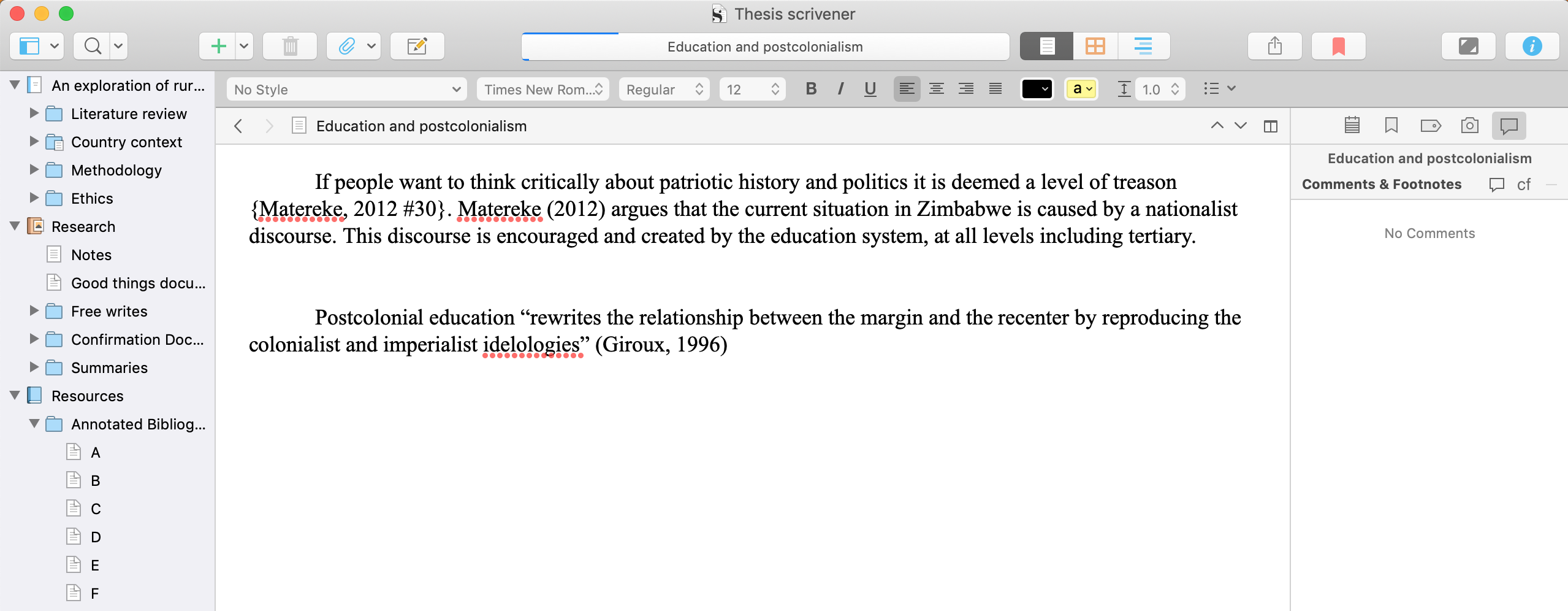

Add some writing to my scrivener file

This part has helped me to actually start writing. Since the beginning of my PhD I have always added sentences to my Scrivener file to match the article I am reading. For example:

This is my scrivener file for my whole PhD. On the left side you can see I have folders set up and each of these contains sub-folders and text within. The top ones are actual chapter drafts that I have begun working on and the ones filed under ‘research’ are things I have randomly written that I am unsure if I will need/what chapter they will be in. The text in this screen here is an example of where I have begun to write about postcolonialism and education. Notice how I have written sentences about what Matereke argues, but also included a quote I think might be relevant. When I begin to write this section later, I can use these as starting points to construct an argument that flows (and actual paragraphs). I will also know what authors I have read who are related to this area. My other files generally have more writing in them than this, but I chose a small example in case someone wants to read the text (to see what I mean)! Let me know if you want more detail on using Scrivener for a PhD!

Code the article in Nvivo

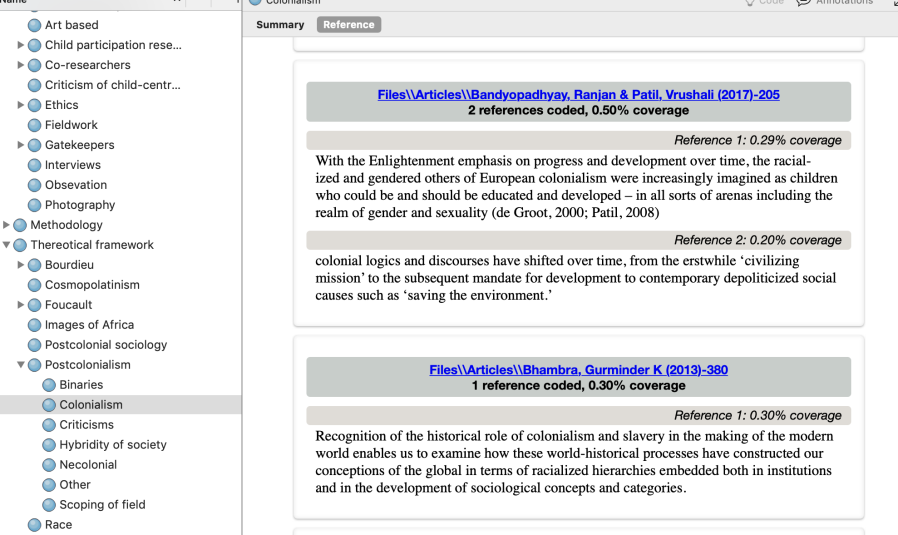

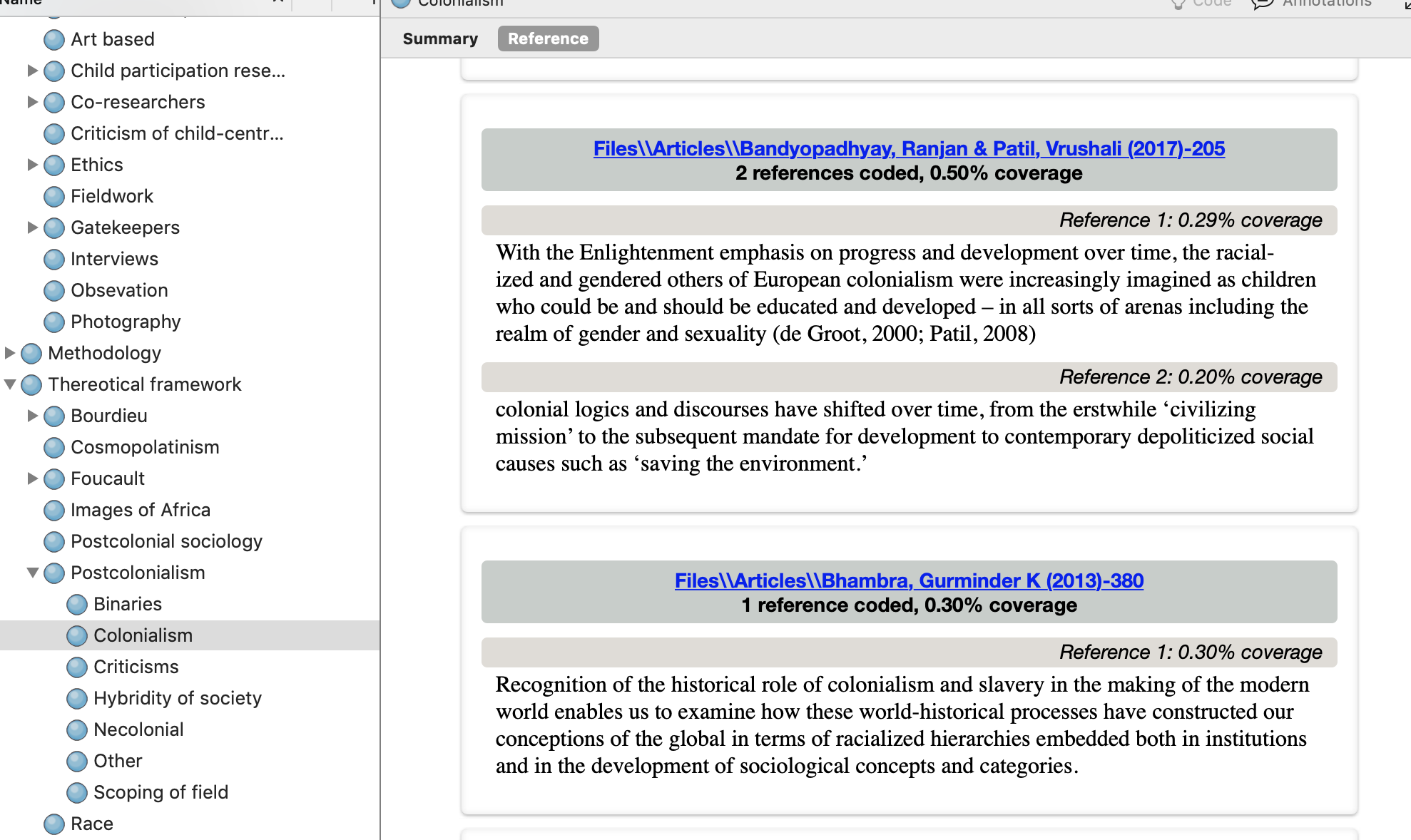

I have already discussed this in my blogpost: Nvivo for a literature review: How and why . I use Nvivo to help me sort my PDFS and find quotes that I like, or in general sentences that I think are really eloquent and helpful at understanding a concept. For example:

A quick glance at my code for ‘colonialism’ allows me to see some ways of writing about colonialism and allows me to remember the key words that are used when discussing this concept (‘civilising mission’ ‘racialised hierachies’ etc).

In conclusion…

I hope this blog has helped you understand the way I take notes, as I have managed to transform from a person who was completely analog with note taking (in undergraduate) to able to work digitally. Not only do I work digitally, I always know where my readings are, how to find something quickly and I don’t start writing with a blank page!

If you are just beginning your PhD, don’t be afraid to find the system that works for you by experimenting with a jigsaw of other people’s methods!

Share this:

10 thoughts on “ the way i take notes for my phd ”.

Thank for sharing Kate. It is a very helpful article.

I’d like to hear bout how you use Scrivener for your PhD, I have not heard bout it until I read your post 🙂

I would also like to hear more about using Scrivener for you PhD! I will be beginning a doctoral program this fall and would love to have a good organization system for articles and research ideas.

Pingback: How I plan in my PhD/Organise my desk – Adventures of a PhD candidate

Love seeing Scrivener incorporated within a note-taking system. Scrivener is probably the best tool in my PhD portfolio! Love it! For those asking, there’s heaps of how-to videos and blogs about using Scrivener for academic work.

thankyou so much. and much love from indonesia… 🙏

The notes you made under education and postcolonialism, did you just keep that in a list of notes with different themes under Research?

And what is Good things docu… just curious 🙂

Hi, yes I just kept them there. In the screenshot I believe you can’t see all my subheadings and folders. I eventually sorted my notes via how I anticipated my chapters would work out so more in headings and subheadings. Then I wrote my actual chapters!

The good things document is where I keep nice feedback I have received etc. it helps when you feel down to be able to see some positive feedback 🙂

Pingback: 3 Other Methods for Taking Notes in your PhD – Adventures of a PhD candidate

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

9 Note-Taking Tips For PhD Research

Taking notes when writing a PhD dissertation or thesis is one of the most important yet daunting tasks for any PhD student.

How you take notes can either make or break your PhD experience.

Luckily, there are some useful tips from previous PhD students that can make this task easier and simpler and make the writing of the PhD dissertation or thesis less tiresome.

This post is a collection of top 9 note-taking tips that have proved to be most useful and effective for majority of PhD students.

1. Choose a note-taking medium that works best for you

Some people work best with the good old paper and pen, while others are more comfortable with digital apps.

The medium doesn’t matter as long as it works for you.

2. Take notes as you read

Every time you read a material, take notes simultaneously. Do not wait to take notes afterwards as the human mind is bound to forget important points.

The reading should be active rather than passive. Active reading ensures that you critically analyse what you are reading and place it in the larger context of your own research and the research done by others.

Ask yourself questions such as:

How does this material support my own research? How relevant is it to what I am doing? Where does it fit in my own paper (does it support my background to the study or fits better in the research methodology)? How does the material relate to what others have written on the same topic? Do the findings support others’ findings or do they contradict them? If the findings contradict previous research, what could explain the contradiction?

For a PhD student, active reading and note-taking is a necessity because you are expected to contribute to the body of knowledge in your field of study.

3. Include full references in your notes

The notes for each material read should start with the reference in the reference style recommended by your school or department.

Referencing your notes cannot be overemphasised.

This will save you lots of time when you start inserting in-text citations and compiling reference lists or bibliographies in your dissertation. You won’t have to worry about where certain notes came from and will save you the headache of going back to look for the correct reference.

4. Include some direct quotes

Direct quotes are useful in some cases as long as they stand out and are not just mere general knowledge. They may include: statistics or data that are relevant to your own research, some interesting findings from the research or the author’s unique interpretation of an issue, etc.

Always include the page number of the material where the quote was borrowed from. Direct quotes have to be referenced together with the page number.

5. Have a system for differentiating your own thoughts from the author’s writings

This is useful for avoiding plagiarism.

It is advisable to write the notes in your own words as much as possible. But sometimes it is impossible to avoid noting down exactly what is in the material even if it will not be used as a direct quote. This is especially the case if you want to remember some points the author made in the material for future reference without having to re-read the material again.

In this case, you need to put a system in place that helps you differentiate your own notes from the writings of the authors. You can use for instance a colour coding system where your own notes are marked by a colour of your choice, the author’s writings are marked by a different colour and the direct quotes are marked by a separate colour.

If you go by a colour coding system, then having key for the different colours used in your notes will be useful to avoid confusion as you go along.

An example of key for colour codes would be:

Red = own notes Blue = author’s writings Yellow = direct quotes

6. Make sure to digitise manual notes

Both pen-and-paper methods and digital methods have their pros and cons.

One advantage of using the pen-and-paper method is that it makes it easier to have clarity of thought. You can also easily add your own comments or insights to the notes.

“Plan in Analog — spend time in analog before jumping to digital” ― Carmine Gallo, The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs

The downside to pen-and-paper method is that the notes can easily get lost or rendered useless, for instance, by spillage.

The other downside to pen-and-paper method is the inability to find something easily. It is time-consuming to peruse through hundreds of pages looking for specific things. Whereas in digital media you can easily use the control F function to find whatever you are looking for.

It is therefore important to digitise manual notes using Microsoft Word or note-taking apps

7. Organise your notes by topics and sub-topics

Instead of organising your notes by authors (like we do in annotated bibliographies ) or by dates, it is best to organise them by topics and sub-topics.

For instance, have a folder for the introduction chapter and create separate files for each sub-topic under the introduction chapter such as: the background to the study, the problem statement, research gap etc.

Do the same for each of your proposal’s or dissertation’s chapters including literature review, research methodology, results and discussion, and lastly the conclusion chapter.

This kind of notes’ organisation will come in handy when writing the proposal or the full dissertation. It will save you time spent going through the notes looking for notes that fit in each of the chapter and their sub-topics.

8. Integrate note-taking with dissertation writing

What I mean is: do not spend a whole year reading materials and taking notes only without writing drafts of the dissertation (or the proposal).

Always write something towards your dissertation on a regular basis.

As an example, you may decide that every Friday you will write 500 words of your dissertation to start with, and then increase the number of words you write as you progress along. So every Friday make use of the notes that you have made at that point and write a sub-topic of your dissertation.

If in the first year you write at least 500 words per week, you will have written at least 26,000 words of your dissertation at the end of the first year. You will then realise that after a while you are able to write 1,000 words and even more in one sitting. The more you write, the easier the writing task becomes.

Keep in mind though, that whatever you write at the beginning is just a draft that you will revise a number of times before it becomes PhD-standard material.

Another important thing to do when writing the drafts of your dissertation is to build the bibliographies or reference list simultaneously, rather than waiting to do this task at the end of your PhD program. Not only will this strategy save you time and headache but it will help you avoid many mistakes in the referencing at the end.

While building your bibliography or reference list be mindful of the required referencing style and always refer to the referencing style manual, even if you are building it with digital softwares such as Zotero. The digital softwares are not always accurate therefore the human eye is a necessity.

9. Build mind maps as you take notes

Mind maps are visual illustrations of the relationships between various concepts. While building the mind maps, include the sources in the notes for easy referencing.

You can build mind maps manually (using pen and paper) or digitally using available mind mapping tools for the different operating systems (such as SimpleMind Pro for MacOS).

Final thoughts on Note-Taking for PhD Students