A literature review of experimental studies in fundraising

Main article content.

Fundraising, Charitable giving, Donations, Experimental methods

This paper extends previous literature reviews focusing on fundraising and the mechanisms motivating charitable giving. We analyze 187 experimental research articles focusing on fundraising, published in journals across diverse disciplines between 2007-2019. Interest in studying fundraising spans many disciplines, each of which tends to focus on different aspects, supporting earlier claims that fundraising has no single academic “home.” Most of the literature focuses on two key areas: the philanthropic environment in which fundraising occurs, largely focused on potential donors’ experiences, preferences, and motivations; and testing fundraising tactics and techniques that result in different behavior by potential donors. More than 40% of the experiments were published in Economics journals. Correspondingly, topics such as warm glow and mechanisms such as lotteries, raffles, and auctions are well represented. Experimental studies largely omit the practical and the ethical considerations of fundraisers and of beneficiaries. For instance, studies focusing on the identified victim phenomenon often stereotype beneficiaries in order to foster guilt among donors and thereby increase giving. We identify several opportunities for research to examine new questions to support ethical and effective fundraising practice and nonprofit administration.

Article Sidebar

Article details.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Manuscripts accepted for publicaction in JBPA are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC-BY 4.0). It allows all uses of published manuscripts but requires attribution.

The CC-BY license applies also to data, code and experimental material, except when it conflicts with a prior copyright. Common courtesy requires informing authors of new uses of their data, as well as acknowledging the source.

Similar Articles

- Heng Qu, Jamie Levine Daniel, Tangible information and charitable giving: When do nonprofit overhead costs matter? , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 4 No. 2 (2021)

- Mirae Kim, Kelly LeRoux, Dyana Mason, Exploring nonprofit dilemmas through a new lens: Introduction to the symposium on experimental and behavioral approaches in nonprofit and voluntary sector research , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 4 No. 2 (2021)

- Margaret Samahita, Leonhard Lades, Compliance Spending Aversion , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 6 (2023)

- Dominik Vogel, Chengxin Xu, Everything hacked? What is the evidential value of the experimental public administration literature? , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 4 No. 2 (2021)

- Yuan Tian, Chiako Hung, Peter Frumkin, Breaking the nonprofit starvation cycle? An experimental test , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 3 No. 1 (2020)

- Aaron Deslatte, A bayesian approach for behavioral public administration: Citizen assessments of local government sustainability performance , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

- Robert K. Christensen, Bradley E. Wright, Public service motivation and ethical behavior: Evidence from three experiments , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2018)

- Laura Doornkamp, Petra Van den Bekerom, Sandra Groeneveld, The individual level effect of symbolic representation: An experimental study on teacher-student gender congruence and students’ perceived abilities in math , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 2 (2019)

- Jurgen Willems, Lewis Faulk, Does voluntary disclosure matter when organizations violate stakeholder trust? , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

- Andrew B Whitford, Holona L Ochs, Experimental tests for gender effects in a principal-agent game , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

1-10 of 25 Next

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Peter D. Lunn, Cameron A. Belton, Ciarán Lavin, Féidhlim P. McGowan, Shane Timmons, Deirdre A. Robertson, Using Behavioral Science to help fight the Coronavirus , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 3 No. 1 (2020)

- Peter John, Toby Blume, How best to nudge taxpayers? The impact of message simplification and descriptive social norms on payment rates in a central London local authority , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2018)

- Asbjørn Sonne Nørgaard, Human behavior inside and outside bureaucracy: Lessons from psychology , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2018)

- Donald Moynihan, A great schism approaching? Towards a micro and macro public administration , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2018)

- Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen, Femke de Vries, Wilte Zijlstra, Breaking bad news without breaking trust: The effects of a press release and newspaper coverage on perceived trustworthiness , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 1 No. 1 (2018)

- Sean Nicholson-Crotty, Jill Nicholson-Crotty, Sean Webeck, Are public managers more risk averse? Framing effects and status quo bias across the sectors , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

- Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen, Peter John, Albert Meijer, Ben Worthy, Do freedom of information laws increase transparency of government? A replication of a field experiment , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

- Maliheh Paryavi, Iris Bohnet, Alexandra van Geen, Descriptive norms and gender diversity: Reactance from men , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2019)

- Marija Aleksovska, Thomas Schillemans, Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen, Lessons from five decades of experimental and behavioral research on accountability: A systematic literature review , Journal of Behavioral Public Administration: Vol. 2 No. 2 (2019)

Modal Header

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

A literature review of experimental studies in fundraising

- Author & abstract

- 59 References

- 3 Citations

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

(Bowling Green State University)

(University of Wisconsin-Whitewater)

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A literature review of experimental studies in fundraising

2020, Journal of Behavioral Public Administration

This paper extends previous literature reviews focusing on fundraising and the mechanisms motivating charitable giving. We analyze 187 experimental research articles focusing on fundraising, published in journals across diverse disciplines between 2007-2019. Interest in studying fundraising spans many disciplines, each of which tends to focus on different aspects, supporting earlier claims that fundraising has no single academic “home.” Most of the literature focuses on two key areas: the philanthropic environment in which fundraising occurs, largely focused on potential donors’ experiences, preferences, and motivations; and testing fundraising tactics and techniques that result in different behavior by potential donors. More than 40% of the experiments were published in Economics journals. Correspondingly, topics such as warm glow and mechanisms such as lotteries, raffles, and auctions are well represented. Experimental studies largely omit the practical and the ethical considerati...

Related Papers

Indranil Goswami

We present a complete empirical case study of fundraising campaign decisions that demonstratesthe importance of in-context field experiments. We first design novel matching-basedfundraising appeals. We derive theory-based predictions from the standard impure altruismmodel and solicit expert opinion about the potential performance of our interventions. Boththeory-based prediction and descriptive advice suggest improved fundraising performance from aframing intervention that credited donors for the matched funds (compared to a typical matchframing). However, results from a natural field experiment with prior donors of a non-profitshowed significantly poorer performance of this framing compared to a regularly framedmatching intervention. This surprising finding was confirmed in a second natural fieldexperiment, to establish the ground truth. Theoretically, our results highlight the limitations ofboth impure altruism models and of expert opinion in predicting complex “warm glow”motivati...

Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics

Ronen Bar-el

Phoebe Koundouri

International Economic Review

Sander Onderstal , ARTHUR Schram

PsycEXTRA Dataset

Sander Onderstal

Craig Landry

Lilia Zhurakhovska

While increasingly popular in many domains crowdfunding remains largely under-researched and little is known about the best way to encourage participation and boost contributions. In an artefactual field experiment we implement a crowdfunding campaign for a club good—an institute’s summer party with free food, drinks, and music—and offer a diverse range of staggered rewards for contributions. In a 2x2 design, we vary suggested amounts (€10 or €20) and test different wordings regarding the nature of contributions. We find that higher suggestions shift the median and the mode of contributions from €5 to €10 while the response rate remains largely unchanged. We also find evidence in favor of a “donation” frame that generates higher income than a straight “contribution” frame which, according to word maps that explore the associative content of the different frames, hints at the role of warm glow. Fundamentally, our results suggest that more experiments to explore the efficacy of crowdfunding campaigns may be as promising as experiments on charitable fundraising have proven to be.

Journal of Public Economics

Ragan Petrie

Laboratory researchers in economics assiduously protect the confidentiality of subjects. Why? Presumably because they fear that the social consequences of identifying subjects and their choices would significantly alter the economic incentives of the game. But these may be the same social effects that institutions, like charitable fund-raising, are manipulating to help overcome free riding and to promote economic efficiency. We present an experiment that unmasks subjects in a systematic and controlled way. We show that, as intuition suggests, identifying subjects has significant effects. Surprisingly, we found that two supplemental conditions meant to mimic common fund-raising practices actually had the most dramatic influences on behavior.

RELATED PAPERS

pekayon 2019

robin dunbar

Carlo Spinedi

Grandon Gill

Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe

Hennie Van Coller

International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents

Ilker Uckay

Emergency Medicine Journal

Jana Šeblová

Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Nuclei in the Cosmos (NIC2016)

Samfundslederskab i Skandinavien

Brian Andersen

Research in Number Theory

Celsa-Beatriz Carrión-Berrú

Christopher Raab

Alexandru NEMTOI

Marina De Rossi

Humanitaire Enjeux Pratiques Debats

Georges Berghezan

ASEAN Marketing Journal

rudi gunawan

Summa Phytopathologica

Leonardo Luiz

The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation

Helga Bergmeister

Archives of Current Research International

Anitha Menon

LK 3.1 Best Practice

arXiv (Cornell University)

Steven Lidia

Ross Altheimer

sabar barokah

Journal of Molecular Liquids

Mohammad Hadi Ghatee

Diagnostics

Susana Espinoza

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration Vol 3(1), pp. 1-19 DOI: 10.30636/jbpa.31.129 Research Article A literature review of experimental studies in fundraising

Abhishek Bhati*, Ruth K. Hansen†

Abstract: This paper extends previous literature reviews focusing on fundraising and the mechanisms moti- vating charitable giving. We analyze 187 experimental research articles focusing on fundraising, published in journals across diverse disciplines between 2007-2019. Interest in studying fundraising spans many disci- plines, each of which tends to focus on different aspects, supporting earlier claims that fundraising has no sin- gle academic “home.” Most of the literature focuses on two key areas: the philanthropic environment in which fundraising occurs, largely focused on potential donors’ experiences, preferences, and motivations; and testing fundraising tactics and techniques that result in different behavior by potential donors. More than 40% of the experiments were published in Economics journals. Correspondingly, topics such as warm glow and mecha- nisms such as lotteries, raffles, and auctions are well represented. Experimental studies largely omit the prac- tical and the ethical considerations of fundraisers and of beneficiaries. For instance, studies focusing on the identified victim phenomenon often stereotype beneficiaries in order to foster guilt among donors and thereby increase giving. We identify several opportunities for research to examine new questions to support ethical and effective fundraising practice and nonprofit administration.

Keywords: Fundraising, Charitable giving, Donations, Experimental methods

onprofit organizations play a central role in organizations is growing, and at the same time N public administration by delivering public government grants and contracts are becoming goods and services along with public agencies increasingly competitive (Bhati, 2018). These recent (Young, 2006). Both government funds and private trends have prompted scholars across disciplines in philanthropy support nonprofit organizations, and the social sciences and public administration to study the constraints upon which that funding is different aspects of fundraising as it directly affects contingent will affect the type and quality of the the success of nonprofit organizations (Kim, Mason, services provided by nonprofits (e.g., Lipsky & Smith, & Li, 2017). 1993; Marwell & Calabrese, 2014). At the same time, Currently, much of this literature in fundraising nonprofits are established to support government focuses on two major areas: (1) who gives, examining entities, such as associations to support libraries sociodemographic details of donors such as income, (Schatteman & Bingle, 2015), schools (Nelson & age, gender, employment, etc.; and (2) why people give, Gazley, 2014), universities (Worth, 2016), or parks investigating personal benefits, values, and incentives (Cheng, 2019). The nonprofit sector is experiencing (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Lindahl & Conley, 2002; increased competition for donations: the number of Waters, 2016; Wiepking & Bekkers, 2012). It has been nearly ten years since the most recent * Assistant Professor, Department of Political comprehensive review (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). Science, Bowling Green State University In that time, scholars have called for research † Assistant Professor, Department of Management, that identifies causal relationships to complement University of Wisconsin - Whitewater other observational and correlational research Address correspondence to Abhishek Bhati at methods (James, Jilke, & Van Ryzin, 2017, p. 3). ( [email protected] ) Copyright: © 2020. The authors license this article Experimental research is a good method by which to under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution test competing explanations and establish causality, 4.0 International License. tying rigorous research methods to real-world

Bhati & Hansen, 2020 practice (Jilke, Van de Walle, & Kim, 2016). Whether giving, only a limited number of public and nonprofit the design emphasizes control (laboratory management studies use experiments” (p. 416). experiments) or external validity (field experiments), Heeding these calls, while also recognizing the experimental research has much to offer to the substantial contribution of studies that use many theorization and practice of fundraising (Kim et al. different and complementary approaches to 2017). Mason (2013) also argues for the importance producing knowledge, we focus here on experiments of randomized, controlled field experiments to better to highlight their contributions to our understanding understand causal relationships, and finds that of fundraising. We systematically review studies using experimental research methods are underrepresented experimental methods during the period 2007 to within a leading nonprofit journal, Nonprofit and 2019 across diverse disciplines. This review extends Voluntary Sector Quarterly. A previous collection of earlier reviews such as Lindahl & Conley (2002) and experimental research on the topic of giving explored Bekkers & Wiepking (2011) (which collected data issues of judgment, decision making, and emotions through 2007) but is also more narrowly focused on (Oppenheimer & Olivola, 2011). More recently, Kim fundraising studies using experimental methods. We et al. (2017) maintain that “despite a growing body of structure the review into two major areas: (1) Donors’ experimental research on altruism and charitable Experiences, Preferences, and Motivations is divided into

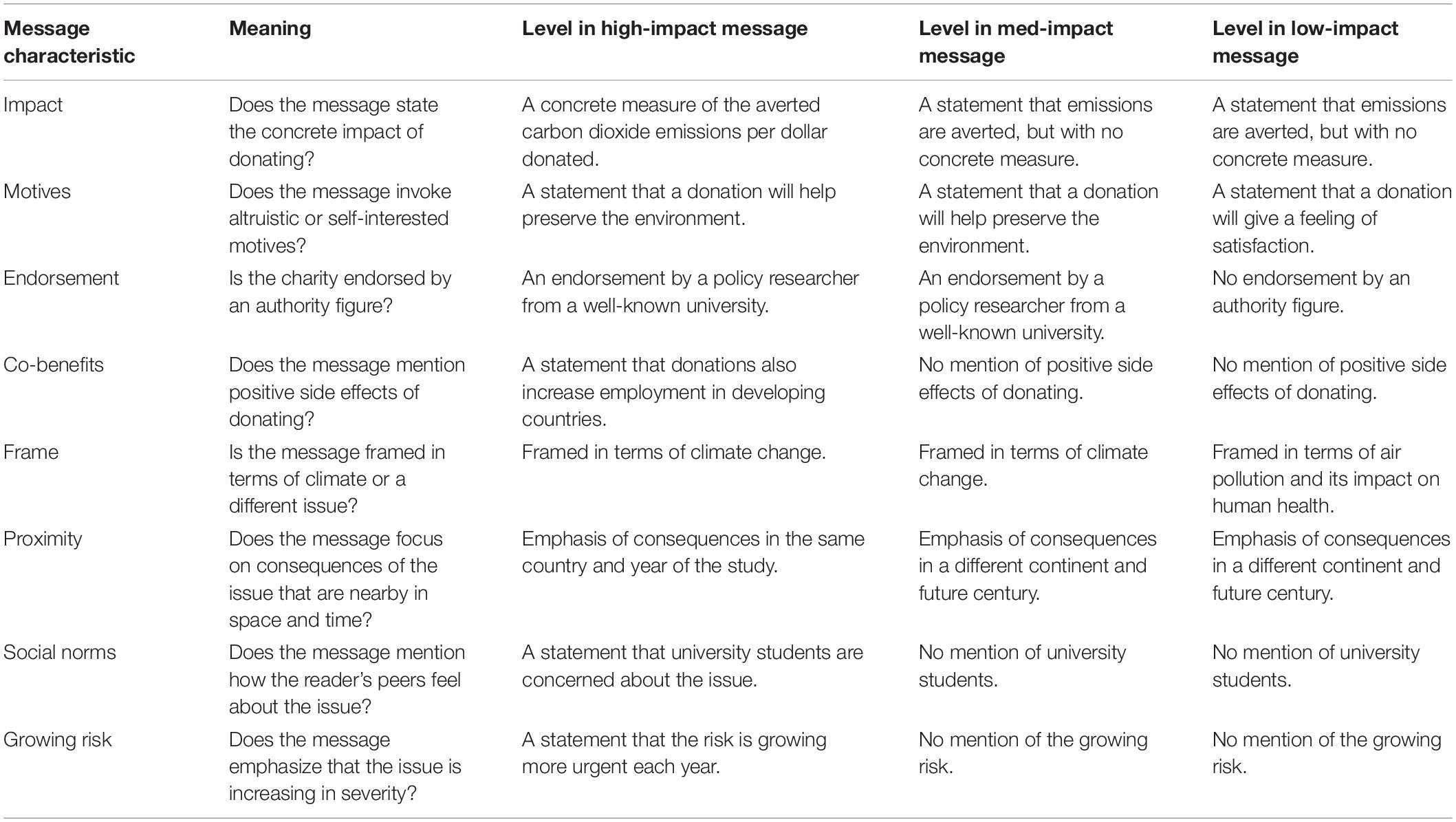

Table 1 Summary of Key Articles Using Experiments in Charitable Giving, 2008-2019

Authors Year Journal Mechanism tested Findings Falk 2007 Eco Solicitation Small gift in mailer increases like- lihood of getting a donation Small, Loewen- 2007 OBHDP Images Sympathy for identified victim stein & Slovic can be suppressed but at the same time sympathy for large scale problem does not increase Dunn, Aknin, & 2008 Science Altruism & warm glow Spending on others increases Norton happiness more than spending on oneself Liu & Aaker 2008 JCR Solicitation Nudging solicitation from amount of money to amount of time increases giving Ariely, Bracha, & 2009 AER Reputation & social In public, people want to be seen Meier pressure as acting prosocially. In private, extrinsic incentives work better. Small & Verrochi 2009 JMR Images Participants are more willing to donate to sad child image than happy Piff, Kraus, Cote, 2010 JPSP Values Lower income individuals are Cheng & Keltner more generous because they sub- scribe to more egalitarian values DellaVigna, List & 2012 QJE Reputation & social In door-to-door solicitation peo- Malmendier pressure ple feel social pressure to say yes Andreoni, Rao & 2017 JPE Reputation & social Making avoidance difficult in- Trachtman pressure creases giving and verbal ask is more effective Note: AER – American Economic Review; Eco- Econometrica; JPSP – Journal of Personality and Social Psychology ; JMR – Journal of Marketing Research; JCR – Journal of Consumer Research; OBHDP – Organizational Behavior and Human Development Processes; QJE – The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1) several themes focusing on (a) the psychological the data. Then, we performed a series of descriptive benefits of giving, such as warm glow (or “joy of analyses of the data, including analyzing papers by giving”), and debates between altruism in the year, by journal, by the primary discipline of the economic sense, altruistic values, and warm glow; (b) journal, and by citations. Finally, we identified key reputation and social pressure; and (c) efficacy and papers among each theme by using the citations values. The second area, (2) Fundraising Practices & index, as suggested by Ma & Konrath (2018). See Techniques is divided into themes focusing on (a) Table 1 for summary of key articles using images and messages; (b) suggesting gift amounts; experiments in charitable giving from 2007 to 2019. and (c) social events such as auctions, raffles, and On average, 15 articles reporting on fundraising walks/runs. Overall, we incorporate practical and the experiments were published each year during this ethical considerations for fundraising practice. period. The largest disciplinary contributor was Economics, with 81 articles published in 31 journals. Methodology & Data Psychology and Social Psychology (combined) published 34 articles in 18 journals; disciplines within We performed an analysis of experimental studies Business (combined) published 29 articles in 15 that help us understand fundraising, reviewing a total journals; and journals focused on some aspect of of 187 articles published in 83 journals across diverse Nonprofit studies (combined with Public disciplines. Articles were identified through a Administration) produced 27 articles in 7 journals. systematic search of (a) online full text of publishers Articles were categorized by the primary focus of the such as Wiley, Emerald, SpringerLink, Sage, and journal in which they were published. Since journals Elsevier; (b) academic databases such as PsychInfo, may serve topics that cross disciplinary fields, the PubMed, Web of Sciences, and EconLit; (c) Google primary description used by the journal itself was Scholar; (d) our own literature databases; and (e) used in categorization. See Appendix A for a references cited in the articles found, using key words complete list of categories and journals, and the such as donations, philanthropy, charitable giving, number of articles in each. fundraising and experimental design. Our analyses synthesize findings, placing them We reviewed papers that were published after within a structure that highlights the duality of donor Bekkers & Wiepking (2011) ceased data collection in motivation and fundraising practice. We also offer a late 2007, and continuing into 2019, performing the critical eye, examining assumptions and the interests search between November 2018 and September of various stakeholders in the fundraising process – 2019. Similar to Lindahl & Conley (2002), we focus the donors, the organizations, its client beneficiaries, on how people and organizations engage in and the fundraisers themselves. Based on this work, fundraising. We limit our analysis to those using we offer suggestions for both research opportunities experimental processes, including public goods and fundraising practice. games, dictator games, etc., which are commonly used within behavioral economics. We excluded Findings studies of donations of blood, tissue, and human biologics. We also excluded studies of donations of In this section, we categorize the fundraising studies time and expertise. Although these are valuable into two major themes: (1) Donors’ Experiences, resources, they are conceptually distinct from the Preferences, and Motivations, focusing on factors why financial focus we typically expect of fundraising donors give money to charities; and (2) Fundraising (Worth, 2016, p. 6). Practices & Techniques, analyzing different methods We used a content analysis approach. For each used by charities in soliciting donations. paper, we developed notes to analyze the key Donors’ Experiences, Preferences, and research questions, experimental methods used, key Motivations. There is an extensive literature on findings, and the number of citations using Google prosocial behavior . Here, we have bounded these Scholar. Then, we carefully developed themes using topics by focusing on those addressing the voluntary both the a priori categories developed by previous donation of money to charities. This section is prominent fundraising literature reviews (Bekkers & divided into three further sections reflecting the most Wiepking, 2011; Lindahl & Conley, 2002), which are prominent themes: (a) altruism, altruistic values, and well-known to nonprofit researchers, and using an warm glow; (b) reputation and social pressure; and (c) iterative process to identify emergent themes from efficacy and values.

Bhati & Hansen, 2020

Altruism, Altruistic Values, and Warm Glow. However, Krishna (2011) argues prosocial spending There is ongoing tension in the literature about may function differently in the case of purchasing motivations of donors to give. Economists have cause-related products, as the purchase may be defined “pure altruism” as concern for a given public perceived as an egoistic act, and therefore not good or outcome, often complemented by “warm increase happiness. Another study found evidence of glow,” a psychological benefit from the act of giving increased giving as a method of guilt reduction in and of itself (Andreoni, 1989; 1990). In our (Ohtsubo & Watanabe, 2013). analysis we found several studies in economics Reputation and Social Pressure. Prior following Andreoni’s work, attempting to parse pure experimental studies have suggested that giving altruism from warm glow. Crumpler & Grossman increases one’s positive self-image, as the donor is (2008) designed an experimental study to isolate and seen as kind and benevolent and experiences an measure the magnitude of warm glow, using six improved reputation (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). sessions of a dictator game with 150 university Bekkers & Wiepking (2011) further state, “the effect students in a laboratory setting. They found that of reputation on giving increases with the value of warm glow was significant and motivated a approval received by donors” (p. 951). In our analysis, substantial portion of giving. In a field experiment we found several studies suggesting that information with 122 children between 3-5 years old, List & about others’ high contributions positively influences Samak (2013) found evidence of pure altruism and participants’ donation, supporting the premise that not warm glow, and argued that warm glow in adults, approval would be perceived as valuable (Croson, as found by Crumpler and Grossman (2008), might Handy, & Shang, 2009; Croson & Shang, 2008; Güth, develop over time through socialization processes. Levati, Sutter, & Heijden, 2007; Huck, Rasul, & The size of the gift considered also seems to be tied Shephard, 2015; Jones & Linardi, 2014; Karlan & to different motivations, with larger donors McConnell, 2014; Kessler, 2017; Kumru & responding better to promotion of charity Vesterlund, 2010; Martin & Randal, 2008; Shang & effectiveness, but smaller donors responding Croson, 2009; Yuan, Wu, & Kou, 2018). One negatively to the same message, suggesting that large prominent field experiment by Shang & Croson wealthy donors are driven by altruism whereas small (2009) found participants, who had already decided donors are motivated by warm glow motives (Karlan to donate, gave more when informed about others’ & Wood, 2017). The closeness of a giver’s high contributions. Similar results were found by relationship to the recipient also affects the size of other studies where donors changed their donations giving, suggesting that the strength of altruistic based on the information of previous contribution behavior may be “target dependent” (Ben-Ner & (Croson et al., 2009; Croson & Shang, 2008; Güth et Kramer, 2011). al., 2007; Huck et al., 2015). Following on this idea of Social psychologists have used altruism to mean social pressure, Martin & Randal (2008) conducted a concern for others, such as the presence of prosocial field experiment in an art museum where they values. Using this approach, undergraduate students manipulated donations by displaying different reported lower intentions to give to Make-A-Wish amounts of money (empty, 50-cent, $5 and $50) in a Foundation when presented with both altruistic and transparent box. The propensity to donate was egoistic motives, compared to either altruistic highest in the 50-cent treatment, indicating a norm to motives or egoistic motives separately, suggesting make a small contribution. that participants may consider altruistic and egoistic People are likely to give more when others are motives as incompatible (Feiler, Tost, & Grant, 2012). present, as they want to be seen as doing good. Even Prosocial spending on others – acting on altruistic the presence of a solicitor creates social pressure, values – promotes happiness for the giver (Aknin, which is difficult to resist (Alpizar, Carlsson, & Dunn, & Norton, 2012; Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, Johansson-Stenman, 2008; Alpizar & Martinsson, 2008; Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2014). Dunn et al. 2013; Andreoni, Rao, & Trachtman, 2017; Ariely, (2014) tested this prosocial spending hypothesis in Bracha, & Meier, 2009; Mason, 2016; Reinstein & 120 countries and found a positive relationship. The Riener, 2012). In an important study conducted by “strength of relationship varied among countries, Ariely et al. (2009) using both laboratory and field individuals in poor and rich countries alike reported experiment methods, people wanted to be seen by more happiness if they engaged in prosocial spending” others when acting prosocially. The presence of a (p. 42), suggesting altruistic values may be universal. solicitor increased donations by 25% over those

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1) made in private among lone travelers in a national or Perceived Donation Efficacy (PDE), does not park in Costa Rica (Alpizar & Martinsson, 2013). have a direct relationship with giving (Carroll & Reinstein & Riener (2012) agree with Bekkers & Kachersky, 2019; Vollan, Henning, & Staewa, 2017). Wiepking (2011) that it is not just being observed that Vollan et al. (2017) suggest that efficacy is not matters, but also the perceived value of the positively associated with fundraising because most observer’s opinion. The strength of the “reputation- donors assume the organization has already earned a seeking effect” they observed depended upon the seal of quality, and therefore emphasizing their nature and closeness of individuals’ relationships efficacy might make donors skeptical. Perhaps with peers in the experiment. Publicly acknowledging concern for effectiveness is also often raised as a participating donors can also increase donations convenient excuse for what is essentially more self- (Mason, 2016). But sometimes the reputation aspect regarding preferences (Exley, 2016). But perhaps the works in favor of social norms for conformity , rather situation matters -- Rasul & Huck (2010) find that the than increased generosity: donors may choose to mere presence of a lead donor signals to others that donate within a popular range to avoid standing out the particular nonprofit is of high quality, increasing in either a positive or negative way (Jones & Linardi, others’ giving. 2014; Zafar, 2011). Large organizations might have more capacity Giving can increase the perceived to bring about changes in the lives of beneficiaries, trustworthiness of donors (Fehrler & Przepiorka, or efficacy towards a cause, but donors may prefer to 2013) and the desirability of both men and women as support smaller organizations (Borgloh, Dannenberg, long-term relationship prospects (Barclay, 2010). & Aretz, 2013; Bradley, Lawrence, & Ferguson, High income (and thus high status) participants can 2019). Borgloh et al. (2013) conducted a field be motivated to give more if they believe that they experiment with non-student populations and found are providing an example for low-income that participants chose small organizations with low participants (Kumru & Vesterlund, 2010). Social revenues over large organizations. They argue that pressure can influence not just the amount, but also preferring small organizations suggests that the likelihood of giving. DellaVigna, List, & participants feel their donation will make more of an Malmendier (2012) studied door-to-door fundraising impact on the small organization’s ability to grow and solicitations and argued that people give because they help the beneficiaries more than a gift to large feel social pressure to say “yes.” Other studies by organizations. Similar “underdog effect” results were Andreoni et al. (2017) and Jasper & Samek (2014) found by Bradley et al., (2019) where donors found similar results. Interestingly, DellaVigna, List, supported the charity with least other support. Malmendier, & Rao (2013) found that men and Other means of evaluating effectiveness include women were equally generous in a door-to-door preferring local giving over giving further away, as solicitation; however, women were less generous if it donors associate physical closeness with greater was easy for them to avoid the solicitor. The impact (Touré-Tillery & Fishbach, 2017), and researchers concluded that women may be more preferencing higher proportions of service over sensitive to social cues, and this may affect their higher absolute numbers (Bartels & Burnett, 2011). prosocial behavior. Men’s social behavior depends Bartels & Burnett (2011) found that experiment on the sex of the observer – they tend to contribute participants preferred a program that saved 50% (50 more when observed by the opposite sex, rather than lives out of 100) to a program that saved 25% (60 a male or no observer, while varying the sex of the lives saved out of 240), despite the fact that the observer “did not significantly vary across three second program saved 10 more lives. observer conditions. Findings support the notion Of course, effectiveness will also be evaluated that men’s generosity might have evolved as a mating differently by people who value different things. signal” (Iredale, Vugt, & Dunbar, 2008, p. 386). Donors see the work of nonprofits as a way to Efficacy and Values. Efficacy refers to the change the world, so whether a particular cause or “perception of donors that contributions make a organization is more or less attractive depends on the difference to the cause they are supporting” (Bekkers values and attitudes of a given donor. Donors want & Wiepking, 2011, p. 942) – and donors are more to improve the issues they care about, and those likely to give if they feel their gift will make a particular issues are tied to their sense of identity. For difference. Surprisingly, some studies in our current instance, people who identify with environmentalism analysis of experimental articles suggest that efficacy, give to environmental organizations (Simon,

Trötschel, & Dähne, 2008). Another important study negative feelings into a positive emotion; so, images in this area examined socioeconomic status, and of a sad child increase giving (Basil, Ridgway, & Basil, found lower income individuals more generous, 2008; Merchant et al., 2010). Fisher & Ma (2014) trusting, helpful, and charitable than their upper-class found using images of attractive children in counterparts (Piff, Kraus, Cote, Cheng, & Keltner, fundraising appeals also led to a negative effect on 2010). They argue that participants with less empathy and actual helping behavior . disposable income are more generous than higher Cockrill & Parsonage (2016) argue that income individuals because lower income shocking images, in isolation, decrease the viewer’s circumstances correlate with more egalitarian values intent to agree with the cause. They found emotions and feelings of compassion . There is also evidence of most associated with an increased likelihood of “karmic-investment” behavior, in which people act helping the charity financially were compassion, relief, more prosocially when they are hoping for the interest, surprise, and shame. However, Albouy satisfactory resolution of an uncertain event, such as (2017) argues that negative emotions such as fear, waiting for an acceptance letter, a job offer, or sadness, and shock increase intent to donate. In a medical test results (Converse, Risen, & Carter, 2012). dictator game, Van Rijn, Barham, & Sundaram- Converse et al. (2012) encourage fundraisers to solicit Stukel (2017) found that using videos that highlight donations when people are awaiting results from the situational difference between donors and uncertain events. Interestingly, Malhotra (2010) beneficiaries (“negative/ traditional” approach) found religious people more likely than non-religious fosters guilt in viewers, and is more effective in individuals to engage in prosocial behavior on days raising donations than using “positive” videos that when they attend services, but on other days the level highlight similarities. Cao & Jia (2017) found that sad of religiosity does not have any behavioral effect. images versus happy images garner stronger donation intentions among participants who were Fundraising Practices & Techniques less involved with the charity, but the reverse was true for highly involved participants. This suggests Studies of fundraising techniques may vary one that committed donors are more able to think though aspect of an appeal in order to observe donor a problem and need of beneficiaries, and hence behaviors such as participation or size of donation. happy images make committed donors feel their In this section, we include three categories that are donation is making a difference. prominent in both the collected experimental Studies have suggested that the framing of literature and in fundraising practice: (a) usage of fundraising written appeals also affects how donors images and messages; (b) suggested ask amount; and perceive the cause, and their subsequent decision to (c) fundraising events: auctions, raffles, and give. A negatively framed fundraising message (the walks/runs. consequences of not giving) was found to be more Usage of Images and Messages. In our effective when coupled with the use of statistical review, we found two prominent themes emerging information about the beneficiaries, while a that focused on the relationship between images in positively framed message (the outcomes of making solicitations and giving: (a) sad versus happy children, a gift) was more effective when coupled with the use and (b) a single child versus a group. Studies suggest of emotional information (Das, Kerkhof, & Kuiper, that images of children with sad faces increase 2008). In addition, participants’ giving intentions sympathy and guilt for not giving among donors, were higher for messages that addressed goal thereby increasing donation intentions (Albouy, 2017; attainment (Chang & Lee, 2009; Das et al., 2008). Allred & Amos, 2018; Cao & Jia, 2017; Cockrill & Chou & Murnighan (2013) found that using a “loss Parsonage, 2016; Fisher & Ma, 2014; Hideg & Van message” (e.g., your action can “prevent a death” – Kleef, 2017; Merchant, Ford, & Sargeant, 2010; Small which is still an outcome of positive action) is more & Verrochi, 2009). In a laboratory experiment with likely to increase intentions to volunteer and donate university students and staff, participants were more than a positive message (e.g., your action can “save a willing to donate when they saw a sad child versus a life”). Erlandsson, Nilsson, & Västfjäll (2018) argue happy child’s face (Small & Verrochi, 2009). Studies that donation behavior and attitudes towards charity by social psychologists argue that the image of a child appeals do not always go hand in hand. They argue with a sad face makes viewers feel guilty or sad, and that it’s “possible to hate a negative charity appeal giving gives them an opportunity to convert such and be angry at the organization behind it but still

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1) donate money after seeking it or alternatively, to love 2018). Using a student population (N=121), Small et a charity appeal and the organization behind it but al. (2007) found that discussing the details about the still refrain from donating” (p. 23). In summary, these full scale of a large problem reduced sympathy studies highlight the cognition discontinuity among towards “identified victims” or single victims, and donors making a decision to give based on seeing did not generate sympathy for the larger number of images of beneficiaries. At one level, donors like to victims. Adding to the findings of Small et al. (2007), see children in a positive light; but they may donate Kogut & Ritov (2007) found that identifying a single to a sad faced child if that image induces sadness and victim increases the participant’s generosity only guilt. when the victim is from a participant’s in-group (i.e. Attribution also plays a role in how messages are sharing participants’ identity name representing perceived. Across experiments, Zagefka, Noor, certain region). Smith et al. (2013) added that donors Brown, de Moura, & Hopthrow (2011) found that may donate to multiple victims when they perceive more donations are given to victims of natural them as entitative – comprising a single coherent unit, disasters than to those affected by human-caused such as a mother with four children. Cryder et al. disasters, such as genocide, because donors feel that (2013) using three field and lab experiments found natural disasters could happen to anyone, and that donors' perception of impact of their donation the victim has no blame in the situation. increases giving as they feel they money is making a Adding to this tension, Hudson, Vanheerde- difference in the lives of the beneficiaries. Hudson, Dasandi, & Gaines (2016), examined the Västfjäll et al. (2014) re-tests the findings by common practice of “traditional” fundraising appeals designing different experiments testing one or more that intentionally appeal to guilt and pity with components together, and finds that affective feeling depictions of “poor, malnourished, suffering, and toward a charitable cause is highest when the victim typically African, children” (Hudson et al., 2016, p.3) is single. They argue that as the number of victims to prompt donations to international development increases, donors feel their contribution will be less organizations. Using a survey experiment (N=701) impactful. However, in a different study by Soyer & Hudson et al. (2016) confirmed that this practice Hogarth (2011), donations increased with the does tend to generate giving, while also priming number of potential beneficiaries, but at a decreasing negative emotions such as repulsion that drive rate. It seems that there is more to learn about this potential donors away and may diminish future phenomenon, as we try to understand the engagement. “Alternative” fundraising appeals, circumstances that affect readers’ perceptions. which highlight commonalities between the Suggested Ask Amount. Several experimental recipients and donors, activate hope rather than guilt studies have focused on the relationship between and anger. “Alternative” appeals also increased the suggesting an amount to give, and the resulting likelihood of a donation and improved readers’ sense behavior (De Bruyn & Prokopec, 2013; Edwards & of personal efficacy. Hence, nonprofits using List, 2014; Fielding & Knowles, 2015; Goswami & “traditional” approaches may be trading long-term Urminsky, 2016; Reiley & Samek, 2019). In one study, effects for short-term donations, and should Edwards & List (2014) asked US college graduates to consider the long-term effects their fundraising donate to their alma mater. Those who received a raising appeals may have on donors. specific ask amount were more likely to respond, and Other scholars have focused on the to send a gift near the suggested number. Similarly, phenomenon known as “identified victim effect,” Fielding & Knowles (2015) found that a verbal where participants are more likely to respond invitation to donate is more impactful than visual emotionally and help single beneficiaries than they clues in isolation, as it acts as peer pressure on the are to help wider groups of individuals (Cryder, donor. Also, the effect of a verbal invitation is larger Loewenstein, & Scheines, 2013; Dickert, Kleber, if participants have more loose change, as it is more Västfjäll, & Slovic, 2016; Erlandsson, Björklund, & convenient to give change and reduce the peer Bäckström, 2015; Genevsky, Västfjäll, Slovic, & pressure and guilt of not making a donation. Knutson, 2013; Hsee, Zhang, Lu, & Xu, 2013; Kogut Often, response cards enclosed with a mailing & Kogut, 2013; Kogut & Ritov, 2007; Small, will have a range of suggested donation amounts, Loewenstein, & Slovic, 2007; Smith, Faro, & Burson, with the first amount referred to as the “anchor,” 2013; Soyer & Hogarth, 2011; Västfjäll, Slovic, because of its ability to anchor perceptions relative to Mayorga, & Peters, 2014; Yeomans & Al-ubaydli, it. Evidence suggests that providing a relatively low

Bhati & Hansen, 2020 anchor will increase the amount of response to the knowledge of others’ bids. Lab experiments have appeal (De Bruyn & Prokopec, 2013; Goswami & tended to support the theory that an all-pay format – Urminsky, 2016), although it may also result in lower in which everyone bidding must pay their bid for an giving per donor than a response card with no item whether or not they win – will result in higher anchoring amount (Goswami & Urminsky, 2016). contributions than the common winner-pay auction De Bruyn & Prokopec (2013) find that is it possible (Faravelli & Stanca, 2012; Schram & Onderstal, 2009). to counteract the effect on gift size by increasing the However, all-pay auctions are not commonly used in amount between each suggested gift, so that there is fundraising. This may be because outside the lab, a steeper increase. However, fundraisers may want people are more likely to perceive a choice as to to keep the suggested amounts in multiples of $5 or whether or not to participate. In natural field $10, as donors seem to prefer round numbers, and it experiments within an existing fundraising event, is easier to give a suggested amount than to pick more people participated, and more was raised, in an another one. In fact, response may be suppressed if auction in which only the winner paid the highest bid “strange” numbers are suggested, because it is easier (Carpenter, Holmes, & Matthews, 2007). Both the to not give than to write in one’s own amount (Reiley prizes offered and charitable inclination are factors & Samek, 2019). affecting bidding. Evidence shows that, within an Donors seem to have internal reference points, auction, some prizes generate more interest than to which suggestions are compared: ask too little or others (Carpenter, et al., 2007). Separately, when too much, and the request will not be persuasive (De identical items were placed for auction in both a non- Bruyn & Prokopec, 2017). Fundraisers can use the charitable context and a charitable context, those in last gift received for guidance in establishing the which a charity or charities benefitted from the anchor amount (De Bruyn & Prokopec, 2013). higher price paid sold for a higher price (Leszczyc & However, introducing any default may also distract Rothkopf, 2010). from other positive information about the charity Raffles. All else being equal, using a lottery or that is included within the appeal (Goswami & raffle prompts people to contribute more than simply Urminsky, 2016). It should also be noted that donors’ asking for donations – people generally respond well giving standards – expectations about appropriate to the chance to win a prize (Lange, List, & Price, donation amounts – vary across different methods of 2007). In a lab experiment using a “self-financing” solicitation, such as door-to-door or direct mail (or 50/50) raffle, in which money is collected in a (Wiepking & Heijnen, 2011). short period of time while participants are present, Fundraising and Events: Auctions, Raffles, and half the money contributed (the “pot”) was and Walks/Runs. Special events are commonly donated to charity, sharing information about the used in fundraising, which may relate to social size of the pot after a first round of ticket sales motivations such as solicitation (being prompted to increased the tickets sold in a second round (Goerg, attend, and subsequent asks throughout an event); Lightle, & Ryvkin, 2016). Another common form of costs and benefits (as in a dinner, entertainment, or a raffle is one in which tickets, each of which chance to win something); altruism (when they care represents one chance to win, are available over a about the organization’s activities); reputation (as in longer period of time, often several weeks, with being seen as a charitable person); psychological proceeds benefiting a local charity. In a field benefits (such as contributing to one’s self-image, or experiment in which proceeds benefited local enjoying the company of others); and values (when poverty relief, Carpenter & Matthews (2017) found the cause being supported aligns well with the that two variations performed better than the individual’s priorities). While no experiments standard linear raffle (in which each ticket sells for addressed the gala-type event, we did find the same price). The highest income resulted from experiments that addressed three aspects commonly pricing with discounts for purchasing more tickets. associated with special events: auctions, raffles, and Another variant, in which people received the same walks/runs for charity: number of chances for any amount donated over a Auctions. Multiple forms of auctions exist, for floor amount, also resulted in higher income than example: oral auctions, in which an auctioneer calls simply selling tickets at a fixed price (Carpenter & out ascending bids; silent auctions, in which bids are Matthews, 2017). written down or communicated electronically; sealed, Charitable Walks/Runs. When people are or blind, auctions, in which bidders have no suffering, such as from cancer, Alzheimer’s disease

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1) or another chronic illness, or depression leading to demographics of likely donors, it would be helpful to suicide, they will donate more when there is effort or test whether other motivations differ systematically, discomfort, such as physical exertion, involved in such as whether older adults’ motivations differ from their donation compared to a similar event that is those of younger or mid-life adults. purely social. This decision is mediated by individuals’ A fourth insight pertains to the role of reputation perception of the act as meaningful, suggesting a and social pressure. Several studies suggested donors psychological benefit (Olivola & Shafir, 2013) contribute more after knowledge of others’ donations (Croson et al., 2009; Croson & Shang, Discussion & Conclusion 2008), which also supports the idea of giving standards raised in Wiepking & Heijnen (2011). This study provides a rigorous review and analysis of A fifth insight is that efficacy (or PDE) toward a experimental studies on charitable fundraising cause does not have a direct relationship with giving reported across many disciplinary journals and joins (Carroll & Kachersky, 2019; Vollan et al., 2017). others in calling for high-quality experimental Studies have suggested that donors tend to support research in the nonprofit fundraising field. We smaller or less supported organizations known as develop themes in two areas: (1) donors’ experiences, “underdog effect” as they feel their giving is making preferences, and motivations, and (2) fundraising a difference to these organizations (Borgloh et al., practices and techniques. Our review of the past 2013; Bradley et al., 2019). Also, Bartels & Burnett decade’s published research suggests that the (2011) found participants are more willing to give to majority centers around donor motivation and programs that save higher proportions of individuals behavior, focusing on why donors give and how even if it means lesser lives as they feel their nonprofits can promote more giving. In this section, contribution is making a difference to a large we share important insights from the review of the percentage of people. literature, followed by suggestions for future Sixth, we found evidence that sad face images researchers of fundraising, and practical insights for increase sympathy and guilt, and thereby increase practitioners. donations (Cao& Jia; Merchant et al., 2010; Small & First, prosocial spending on others promotes Verrochi, 2009), and that donors respond to an happiness and warm glow among donors (Aknin et “identified victim effect” (Cryder et al., 2013; Dickert al. 2012; Dunn et al. 2008; Dunn et al., 2014). et al., 2016; Genevsky et al., 2013). Hudson et al. Second, “warm glow,” or the “joy of giving,” may (2016) suggest that charities should adopt a long- result from a socialization process, as evidence term strategy to cultivate and educate donors about suggests children give because of pure altruism (List the real issues rather than simply focusing on & Samak, 2013). That said, a recent study by Body, emotional images or message framing to attract more Lau & Josephidou (2019) highlighted the common donations in the short term. One way to educate practice of encouraging transactional fundraising donors is by bringing more voices of beneficiaries in among children, such as encouraging fundraising fundraising and tell more complete stories, efforts through incentive rewards, rather than particularly about needy or marginalized people, engaging children about their ideas and values about rather than just overwhelmingly focusing on donor giving. They argue that a more critical engagement of motivation to give (Bhati & Eikenberry, 2016). Also, children in ideas of giving often results in increased the relationship between the race of beneficiaries and effort to support causes that matter to them – generosity should be further explored to understand potentially a different goal than that of the whether how beneficiaries are represented is leading organizations incentivizing the transactional to stereotyping poor and contributing to racial bias fundraising efforts. This both illustrates the (Fong & Luttmer, 2011). socialization process in action, and suggests that a Seventh, lab experiments support the argument different approach to engaging with children around of an all pay auction format (Faravelli & Stanca, 2012; fundraising can support their altruistic impulses. Schram & Onderstal, 2009; but see our caveats below Third, Karlan & Wood (2017) suggested donor under Practical and Ethical Considerations and Future motivation differs based on the size of the gift. For Research), and that raffles promote giving (Lange et al., instance, they found that large donors are driven by 2007). altruism; on the other hand, smaller donors are Eighth, we found only handful of studies driven by warm glow motives. Given the focusing on using experimental design outside of

U.S., consistent with the findings of Ma & Konrath that fundraising has no single “academic home in (2018) regarding most of the nonprofit literature, higher education” (Mack, Kelly, & Wilson, 2016, p. including experimental studies in nonprofits, is 180), but the disciplines prevalent in our review differ produced in Anglosphere countries. from those previously identified - Public Relations, Ninth, very few of the experiments addressed Marketing, and Nonprofit Management (Mack et al. issues of fundraising management. Studies explored 2016). We examined the top ten ranked articles for the importance of task significance in fundraising citations. Of these, five addressed donor motivation performance (Grant, 2008); potential donors’ and behavior; one examined task significance – an response to the communication implicit within issue of interest broadly within organizational fundraisers’ titles in the context of a possible behavior, but here analyzed specifically using sophisticated charitable gift (James, 2016); and the fundraisers; and six studied strategic considerations cultural embeddedness of donor behavior across of fundraising practice. Of the top ten, four were international borders (Banerjee & Chakravarty, 2014; Economics journals, three were Business journals, Špalek & Berná, 2012; see Wiepking & Handy, 2015 and two were Psychology journals. On the one hand, for a more comprehensive treatment). Given the the distribution suggests that the most influential reliance of charitable organizations on both the journals in experimental fundraising research are not income generated by charitable gifts and, relatedly, among those focused primarily on Public, Nonprofit, having the right staff in place to meet fundraising or Philanthropic Studies. On the other hand, goals (Nonprofit Research Collaborative, 2015), Economics, Business, and Psychology are all well- issues of management in fundraising in the U.S. and established areas of study with large numbers of around the world seem a worthy avenue for further affiliated scholars, and we do not know whether the research. For example, when one compares the scholars citing these articles are studying fundraising activities of fundraising (Breeze, 2017) with the or some other related topic. That analysis is beyond definition of leadership as “the ability to influence a the scope of this paper. group toward the achievement of a vision or set of Practical and Ethical Considerations and Future goals” (Robbins & Judge, 2019), an entire arm of Research: Past economic research has been leadership literature can be implicated in enthusiastic about structuring charitable auctions in understanding how fundraisers work with donors all-pay formats to increase the funds contributed, and organizations. although since evidence from field experiments is at A less bright, but ethically important odds with evidence from laboratory experiments, management topic involves the interaction of social research into the boundary conditions is needed preferences and hiring practices. In a study of door- (Schram & Onderstal, 2009). However, there are to-door fundraising in North Carolina, minority other considerations, among them legal and ethical fundraisers received fewer gifts, and a lower total standards. Auctions are often regulated, and are not amount, compared to Caucasian fundraisers, legal in all jurisdictions (National Council of regardless of the race of the household approached Nonprofits, 2019). Additionally, money paid for bids (List & Price, 2009). Sadly, this is consistent with at auction or chances at a lottery are not tax other evidence of widespread racial bias. Nonprofits, deductible for charitable purposes in the US, particularly those with a mission of promoting social although donations are. In recent years, the paddle justice, should consider how to incorporate this raise has gained popularity, in which an audience is mission into their administrative practice, as well as given a short presentation about the charity’s work, raising funds for their programs. and an auctioneer invites people to raise their auction Tenth, although there is a robust experimental paddles (or their hands) to make a publicly observed fundraising literature, these studies are not often pledge to donate at a given level, with no material published in journals focusing on Public, Nonprofit, prize. Since the charity benefits similarly and the cost or Philanthropic Studies. While there is evidence that is less for the individual donating (compared to Nonprofit Studies may be consolidating as a bidding), it may be ethically preferable for fundraisers discipline (Ma & Konrath, 2018), examining the past to prefer paddle raises over all-pay auction formats. twelve years’ evidence demonstrates that fundraising Therefore, we cannot support the enthusiastic is also studied experimentally across many other recommendations for fundraising practitioners to fields, notably Economics, Psychology, and Business. embrace all-pay auctions, but we do recommend that This finding aligns with others who have asserted researchers evaluate the relative effectiveness of the-

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1) se two options. experimental research is incomplete, at best, and In this paper, we found that the majority of the biased at worst. Just as managing for short term literature on fundraising techniques focuses on results can have negative consequences for the long donor motivations and behavior: very few studies term, the emphasis on short term fundraising results focus on beneficiaries or fundraisers. Generally, most may not be a good strategy in the long term for the experiments focusing on fundraising practices and charity, its donors, or its clients. For example, if a techniques focus on donors’ responses, with the goal charity, responding to experimental evidence, of increasing the amount of money transferred to the intentionally induces feelings of shock or shame so charity. Lab experiments, in particular, tend to that people can relieve those feelings with a gift, what measure one-shot transactional giving opportunities, is the long-term effect of people’s willingness to read representing the effort of constantly trying to acquire charitable appeals? How does it affect how they new donors, and they may treat the kind of charity think of that charity? How does it affect how they recipient as generic. Research design decisions are think of the people served by that charity? Evidence sometimes oddly contradictory to studies of donor from a study on global poverty suggests that such motivation, which show that donors’ giving decisions tactics do negatively affect readers’ perception of are strongly aligned to their values, preferences, and efficacy (Hudson, et al., 2016). Considerations such identity, and that strong attachment to a charity or a as this inform fundraising professional codes of cause results in different evaluation choices than a ethics, such as that of the Association of Fundraising casual or prospective donor. While these Professionals (AFP, 1964, 2014). Similarly, if experiments may have high internal validity, real- fundraisers take to heart the “Karmic Investment” world circumstances may result in different behavior approach, soliciting donations when people are than that performed in the lab (e.g. all-pay auctions awaiting results from uncertain events (Converse et perform well in lab experiments (Schram & al., 2012), it may result in predatory behavior and Onderstal, 2009; Faravelli & Stanca, 2012) but see exploiting vulnerabilities to raise donations in the poor participation in field experiments (Carpenter et short term. This is counter to a professional “duty al, 2007). Similarly, recommended fundraising of care” for donors (Lewis, 2019), or, put another practice includes acquiring new donors – but also way, valuing the interests and well-being of donors retaining them, engaging them, and cultivating a (AFP, 1964, 2014). We encourage researchers to closer relationship, which is understood to result in a consider ethical ideals and practice when designing change in behavior over time (Worth, 2016). studies and considering their application. Working with existing donors requires different Practical Considerations for Fundraisers: strategies than acquiring first time donors, notably incorporating donor stewardship, an element of • Auctions: Research supports the received fundraising practice that incorporates elements of wisdom that prizes should be selected with the demonstrating gratitude to donors, responsibility to audience in mind, and that more people will stakeholders, reporting on project developments, participate (and more money will be raised) by and relationship nurturing strategies (Waters, 2009). continuing to have only the winner with the Similarly, the motivations of individuals who give highest bid pay, rather than requiring all bidders may change as they interact with and continue to to pay, regardless of who wins the prize. support a charity, often increasing their commitment • Raffles: In states where charitable raffles are over time (e.g. Karlan & Wood, 2017). In 2018, 97% legal, charities can increase the funds raised by of American and Canadian charities surveyed either giving a volume discount for purchasing reported using major gift and planned giving a greater number of tickets, or by selling tickets methods, which rely on these relationship-building as “pay what you want” with a floor price. If the strategies (Nonprofit Research Collaborative, 2019). raffle is a 50/50, sell tickets in at least two waves, This practice tends to be highly individual, which is and share the size of the pot before beginning harder to examine experimentally, but survey the second wave. research has confirmed that donors who give more • Walks/ Runs: These work best when benefitting often perceive a stronger relationship with the a cause where people are suffering, not causes organization than one-time donors (Waters, 2008). for human enjoyment. Treat the participants’ This raises an ethical aspect in recognizing that exertion as a tribute to others in need. the emphasis on short term fundraising results in • Stewardship: Make use of stewardship materials

to not only thank donors, but also to educate & Wiepking (2011) review of donor motivations, them further about the issues and whole tying the recent experimental literature of this supply personhood of the clients benefitting from their side of philanthropy to its counterpart on the gifts. This may include addressing a fuller scope demand side: fundraising practice. We offer a of issues, some policy considerations, etc. – but stakeholder-informed perspective of both the should in all cases take care not to diminish the practices of fundraising and the research that informs personhood of clients by reducing their voice or it. Finally, we offer suggestions to both researchers agency. Instead, build on commonalities and practitioners in the area of charitable fundraising. between the clients and donors. Acknowledgments This paper updates and consolidates our knowledge of experimental studies across multiple behavioral The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and professional disciplines that inform the practice for their helpful suggestions, Richard Steinberg, of fundraising. It reviews the disciplines and outlets Andrew Burk, and session participants at the 2019 for this research, and selectively extends the Bekkers ARNOVA conference.

Aknin, L., Dunn, E., & Norton, M. (2012). Happiness runs https://afpglobal.org/sites/default/files/attachment in a circular motion: Evidence for a positive feedback s/2019-03/CodeofEthics.pdf loop between prosocial spending and happiness. Banerjee, P., & Chakravarty, S. (2014). Psychological Journal of Happiness, 13(2), 347–355. ownership, group affiliation and other-regarding Albouy, J. (2017). Emotions and prosocial behaviours: A behaviour: Some evidence from dictator games. study of the effectiveness of shocking charity Global Economics and Management Review, 19(1–2), 3–15. campaigns. Recherche et Applications En Marketing, 32(2), Barclay, P. (2010). Altruism as a courtship display: Some 4–25. effects of third-party generosity on audience Allred, A., & Amos, C. (2018). Disgust images and perceptions. British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), 123– nonprofit children’s causes. Journal of Social Marketing, 135. 1(8), 120–140. Bartels, D., & Burnett, R. (2011). A group construal Alpizar, F., Carlsson, F., & Johansson-stenman, O. (2008). account of drop-in-the-bucket thinking in policy Anonymity, reciprocity, and conformity: Evidence preference and moral judgment. Journal of Experimental from voluntary contributions to a national park in Social Psychology, 47(1), 50–57. Costa Rica. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5-6), 1047– Basil, D., Ridgway, N., & Basil, M. (2008). Guilt and giving: 1060. A process model of empathy and efficacy. Psychology Alpizar, F., & Martinsson, P. (2013). Does it matter if you & Marketing, 25(1), 1–23. are observed by others? Evidence from donations in Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of the field. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 115(1), empirical studies of philanthropy. Nonprofit and 74–83. Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924-973. Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Ben-ner, A., & Kramer, A. (2011). Personality and altruism Applications to charity and Ricardian in the dictator game: Relationship to giving to kin, equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1447- collaborators competitors, and neutrals. Personality and 1458. Individual Differences, 51(3), 216–221. Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to Bhati, A. (2018). Market, gender, race: Representation of poor public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The people in fundraising materials used by international Economic Journal, 100(401), 464-477. nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) (Published Andreoni, J., Rao, J., & Trachtman, H. (2017). Avoiding doctoral dissertation). University of Nebraska at the ask: A field experiment on altruism, empathy, and Omaha, U.S. charitable giving. Journal of Political Economy, 125(3), Bhati, A., & Eikenberry, A. (2016). Faces of the needy: The 625–653. portrayal of destitute children in the fundraising Ariely, B., Bracha, A., & Meier, S. (2009). Doing good or campaigns of NGOs in India. International Journal of doing well? Image motivation and monetary Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Marketing, 21(1), 31–42. incentives in behaving prosocially. American Economic Body, A., Lau, E., & Josephidou, J. (2019). Engaging Review, 99(1), 544-555. children in meaningful charity: Opening‐up the Association of Fundraising Professionals. (1964; 2014). spaces within which children learn to give. Children & Code of ethical standards. Society. DOI:10.1111/chso.12366.

Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1)

Borgloh, S., Dannenberg, A., & Aretz, B. (2013). Small is evidence on persuasion . Journal of Applied beautiful — Experimental evidence of donors’ Communication Research, 36(2), 161-175. preferences for charities. Economics Letters, 120(2), De Bruyn, A., & Prokopec, S. (2013). Opening a donor ’s 242–244. wallet: The influence of appeal scales on likelihood Bradley, A., Lawrence, C., & Ferguson, E. (2019). When and magnitude of donation. Journal of Consumer the relatively poor prosper: The underdog effect on Psychology, 23(4), 496–502. charitable donations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector DellaVigna, S., List, J., & Malmendier, U. (2012). Testing Quarterly, 48(1), 108-127. for altruism and social pressure in charitable giving. Breeze, B. (2017). The new fundraisers: Who organises charitable Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 1–56. giving in contemporary society? Policy Press. DellaVigna, S., List, J., Malmendier, U., & Rao, G. (2013). Cao, X., & Jia, L. (2017). The effects of the facial The importance of being marginal: Gender expression of beneficiaries in charity appeals and differences in generosity. American Economic Review, psychological involvement on donation intentions. 103(3), 586-590. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 27(4), 457–473. Dickert, S., Kleber, J., Västfjäll, D., & Slovic, P. (2016). Carpenter, J., Holmes, J., & Matthews, P. (2007). Charity Mental imagery, impact, and affect: A mediation auctions: A field experiment. The Economic Journal, model for charitable giving. PLoS ONE, 11(2), 118(525), 92–113. e0148274. Carpenter, J., & Matthews, P. H. (2017). Using raffles to Dunn, E., Aknin, L., & Norton, M. (2008). Spending fund public goods: Lessons from a field experiment. money on others promotes happiness. Science, Journal of Public Economics, 150, 30–38. 319(5870), 1687–1688. Carroll, R., & Kachersky, L. (2019). Service fundraising Dunn, E., Aknin, L., & Norton, M. (2014). Prosocial and the role of perceived donation efficacy in spending and happiness: Using money to benefit individual charitable giving. Journal of Business Research, others pays off. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 99, 254–263. 23(1), 41-47. Chang, C.-T., & Lee, Y.-K. (2009). Framing charity Edwards, J., & List, J. (2014). Toward an understanding of advertising: Influences of message framing, image why suggestions work in charitable fundraising: valence, and temporal framing on a charitable appeal1. Theory and evidence from a natural field experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(12), 2910–2935. Journal of Public Economics, 114, 1–13. Cheng, Y. (2019). Nonprofit spending and government Erlandsson, A., Björklund, F., & Bäckström, M. (2015). provision of public services: Testing theories of Emotional reactions, perceived impact and perceived government – nonprofit relationships. Journal of Public responsibility mediate the identifiable victim effect, Administration Research and Theory, 29(2), 238–254. proportion dominance effect and in-group effect Chou, E., & Murnighan, J. (2013). Life or death decisions: respectively. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Framing the call for help. PLoS ONE, 8(3) e57351. Process, 127, 1–14. Cockrill, A., & Parsonage, I. (2016). Hocking people into Erlandsson, A., Nilsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2018). action: Does it still work? An empirical analysis of Attitudes and donation behavior when reading emotional appeals in charity advertising. Journal of positive and negative charity appeals. Journal of Advertising Research, 56(1), 401–413. Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 30(4), 444–474. Converse, B., Risen, J., & Carter, T. (2012). Investing in Exley, C. (2016). Excusing selfishness in charitable giving: Karma: When wanting promotes helping. Psychological The role of risk. The Review of Economic Studies, 83(2), Science, 23(8), 923-930. 587–628. Croson, R., Handy, F., & Shang, J. (2009). Keeping up with Falk, A. (2007). Gift exchange in the the Joneses: The relationship of perceived descriptive field. Econometrica, 75(5), 1501-1511. social norms, social information, and charitable giving. Faravelli, M., & Stanca, L. (2012). Single versus multiple- Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 19(4), 467–489. prize all-pay auctions to finance public goods: An Croson, R., & Shang, J. (2008). The impact of downward experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and social information on contribution decisions. Organization, 81(2), 677–688. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 221–233. Fehrler, S., & Przepiorka, W. (2013). Charitable giving as Crumpler, H., & Grossman, P. (2008). An experimental a signal of trustworthiness: Disentangling the test of warm glow giving. Journal of Public Economics, signaling benefits of altruistic acts. Evolution and 92(5), 1011–1021. Human Behavior, 34(2), 139-145. Cryder, C., Loewenstein, G., & Scheines, R. (2013). The Feiler, D., Tost, L., & Grant, A. (2012). Mixed reasons, donor is in the details. Organizational Behavior and missed givings: The costs of blending egoistic and Human Decision Processes, 120(1), 15–23. altruistic reasons in donation requests. Journal of Das, E., Kerkhof, P., & Kuiper, J. (2008). Improving the Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1322–1328. effectiveness of fundraising messages: The impact of Fielding, D., & Knowles, S. (2015). Can you share some charity goal attainment, message framing, and change for charity? Experimental evidence on verbal