Behavioral Ethics: Ethical Practice Is More Than Memorizing Compliance Codes

- Discussion and Review Paper

- Published: 15 June 2021

- Volume 14 , pages 1169–1178, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Frank R. Cicero ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3486-2189 1

2102 Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Disciplines establish and enforce professional codes of ethics in order to guide ethical and safe practice. Unfortunately, ethical breaches still occur. Interestingly, it is found that breaches are often perpetrated by professionals who are aware of their codes of ethics and believe that they engage in ethical practice. The constructs of behavioral ethics, which are most often discussed in business settings, attempt to explain why ethical professionals sometimes engage in unethical behavior. Although traditionally based on theories of social psychology, the principles underlying behavioral ethics are consistent with behavior analysis. When conceptualized as operant behavior, ethical and unethical decisions are seen as being evoked and maintained by environmental variables. As with all forms of operant behavior, antecedents in the environment can trigger unethical responses, and consequences in the environment can shape future unethical responses. In order to increase ethical practice among professionals, an assessment of the environmental variables that affect behavior needs to be conducted on a situation-by-situation basis. Knowledge of discipline-specific professional codes of ethics is not enough to prevent unethical practice. In the current article, constructs used in behavioral ethics are translated into underlying behavior-analytic principles that are known to shape behavior. How these principles establish and maintain both ethical and unethical behavior is discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Ethical Behavior Analysis: Evidence-Based Practice as a Framework for Ethical Decision Making

Making behavioral ethics research more useful for ethics management practice: embracing complexity using a design science approach, ethical behavior as a product of cultural design.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). Occupational therapy code of ethics . https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Ethics.aspx

American Physical Therapy Association. (2019). Code of ethics for the physical therapist . https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/Ethics/CodeofEthics.pdf

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct . https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Code of ethics . https://www.asha.org/Code-of-Ethics/

Ashforth, B. E., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25 , 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25001-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Baum, C. G., Forehand, R., & Zegiob, L. E. (1979). A review of observer reactivity in adult-child interactions. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 1 (2), 167–178.

Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts . Littleton, Co.: Author.

Bowman, J. S. (2018). Thinking about thinking: Beyond decision-making rationalism and the emergence of behavioral ethics. Public Integrity, 20 , 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2017.1410461 .

Cameron, J. S., & Miller, D. T. (2009). Ethical standards in gain versus loss frames. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making (pp. 91–106). Information Age Publishing.

Chugh, D., & Kern, M. C. (2016). A dynamic and cyclical model of bounded ethicality. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36 , 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.07.002 .

Cialdini, R., Li, Y. J., Samper, A., & Wellman, N. (2019). How bad apples promote bad barrels: Unethical leader behavior and the selective attrition effect. Journal of Business Ethics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04252-2 .

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

Cox, D. J. (2020). Descriptive and normative ethical behavior appear to be functionally distinct. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis . https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.761 .

Dana, J., & Loewenstein, G. (2003). A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290 (2), 252–255. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.2.252 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

De Cremer, D. (2009). Psychology and ethics: What it takes to feel ethical when being unethical. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making (pp. 3–13). Information Age Publishing.

De Cremer, D., Mayer, D. M., & Schminke, M. (2010). On understanding ethical behavior and decision making: A behavioral ethics approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20 (1), 1–6.

Drumwright, M., Prentice, R., & Biasucci, C. (2015). Behavioral ethics and teaching ethical decision making. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 13 (3), 431–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12071 .

Duska, R. F. (2017). Unethical behavioral finance: Why good people do bad things. Journal of Financial Service Professionals, 71 (1), 25–28.

Google Scholar

Feldman, Y., Gauthier, R., & Schuler, T. (2013). Curbing misconduct in the pharmaceutical industry: Insights from behavioral ethics and the behavioral approach to law. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics, 41 (3), 620–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12071 .

James Jr., H. S. (2000). Reinforcing ethical decision making through organizational structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 28 (1), 43–58.

Loewenstein, G., Issacharoff, S., Camerer, C., & Babcock, L. (1993). Self-serving assessments of fairness and pretrial bargaining. Journal of Legal Studies, 22 (1), 135–159.

Michael, J. (2004). Concepts and principles of behavior analysis (Rev. ed.). Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Human Relations, 18 (1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872676501800105 .

Moore, C. (2009). Psychological processes in organizational corruption. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making (pp. 35–71). Information Age Publishing.

O’Brien, K., Wittmer, D., & Ebrahimi, B. P. (2017). Behavioral ethics in practice: Integrating service learning into a graduate business ethics course. Journal of Management Education, 41 (4), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562917702495 .

Prentice, R. (2014). Teaching behavioral ethics. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 31 (2), 325–365.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2009). On the causes and conditions of moral behavior: Why is this all we know? In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making (pp. 17–33). Information Age Publishing.

Rosenberg, N. E., & Schwartz, I. S. (2019). Guidance or compliance: What makes an ethical behavior analyst? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12 (2), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-00287-5 .

Schwartz, M. S. (2017). Teaching behavioral ethics: Overcoming the key impediments to ethical behavior. Journal of Management Education, 41 (4), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562917701501 .

Sheridan, C. L., & King, R. G. (1972). Obedience to authority with an authentic victim. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 7 (1), 165–166.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior . Free Press.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behavior. Social Justice Research, 17 (2), 223–236.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32 (6), 951–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294258 .

Wazana, A. (2000). Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: Is a gift ever just a gift? Journal of the American Medical Association, 283 (3), 373–380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.3.373 .

Zhong, C., Liljenquist, K., & Cain, D. M. (2009). Moral self-regulation: Licensing and compensation. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making (pp. 75–89). Information Age Publishing.

Download references

Availability of data and materials

The current article does not include the collection of original data.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Studies, Seton Hall University, 400 South Orange Ave, South Orange, NJ, 07079, USA

Frank R. Cicero

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The idea for the current work, completion of the literature review, writing of the manuscript, and any revisions were and will be the work of the author.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Frank R. Cicero .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The author has no conflicts of interest or competing interests to disclose with regard to the current article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cicero, F.R. Behavioral Ethics: Ethical Practice Is More Than Memorizing Compliance Codes. Behav Analysis Practice 14 , 1169–1178 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00585-5

Download citation

Accepted : 31 March 2021

Published : 15 June 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-021-00585-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Behavioral ethics

- Ethical decisions

- Professionalism

- Interdisciplinary

- Behavior analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih clinical research trials and you, guiding principles for ethical research.

Pursuing Potential Research Participants Protections

“When people are invited to participate in research, there is a strong belief that it should be their choice based on their understanding of what the study is about, and what the risks and benefits of the study are,” said Dr. Christine Grady, chief of the NIH Clinical Center Department of Bioethics, to Clinical Center Radio in a podcast.

Clinical research advances the understanding of science and promotes human health. However, it is important to remember the individuals who volunteer to participate in research. There are precautions researchers can take – in the planning, implementation and follow-up of studies – to protect these participants in research. Ethical guidelines are established for clinical research to protect patient volunteers and to preserve the integrity of the science.

NIH Clinical Center researchers published seven main principles to guide the conduct of ethical research:

Social and clinical value

Scientific validity, fair subject selection, favorable risk-benefit ratio, independent review, informed consent.

- Respect for potential and enrolled subjects

Every research study is designed to answer a specific question. The answer should be important enough to justify asking people to accept some risk or inconvenience for others. In other words, answers to the research question should contribute to scientific understanding of health or improve our ways of preventing, treating, or caring for people with a given disease to justify exposing participants to the risk and burden of research.

A study should be designed in a way that will get an understandable answer to the important research question. This includes considering whether the question asked is answerable, whether the research methods are valid and feasible, and whether the study is designed with accepted principles, clear methods, and reliable practices. Invalid research is unethical because it is a waste of resources and exposes people to risk for no purpose

The primary basis for recruiting participants should be the scientific goals of the study — not vulnerability, privilege, or other unrelated factors. Participants who accept the risks of research should be in a position to enjoy its benefits. Specific groups of participants (for example, women or children) should not be excluded from the research opportunities without a good scientific reason or a particular susceptibility to risk.

Uncertainty about the degree of risks and benefits associated with a clinical research study is inherent. Research risks may be trivial or serious, transient or long-term. Risks can be physical, psychological, economic, or social. Everything should be done to minimize the risks and inconvenience to research participants to maximize the potential benefits, and to determine that the potential benefits are proportionate to, or outweigh, the risks.

To minimize potential conflicts of interest and make sure a study is ethically acceptable before it starts, an independent review panel should review the proposal and ask important questions, including: Are those conducting the trial sufficiently free of bias? Is the study doing all it can to protect research participants? Has the trial been ethically designed and is the risk–benefit ratio favorable? The panel also monitors a study while it is ongoing.

Potential participants should make their own decision about whether they want to participate or continue participating in research. This is done through a process of informed consent in which individuals (1) are accurately informed of the purpose, methods, risks, benefits, and alternatives to the research, (2) understand this information and how it relates to their own clinical situation or interests, and (3) make a voluntary decision about whether to participate.

Respect for potential and enrolled participants

Individuals should be treated with respect from the time they are approached for possible participation — even if they refuse enrollment in a study — throughout their participation and after their participation ends. This includes:

- respecting their privacy and keeping their private information confidential

- respecting their right to change their mind, to decide that the research does not match their interests, and to withdraw without a penalty

- informing them of new information that might emerge in the course of research, which might change their assessment of the risks and benefits of participating

- monitoring their welfare and, if they experience adverse reactions, unexpected effects, or changes in clinical status, ensuring appropriate treatment and, when necessary, removal from the study

- informing them about what was learned from the research

More information on these seven guiding principles and on bioethics in general

This page last reviewed on March 16, 2016

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 February 2024

Bounded research ethicality: researchers rate themselves and their field as better than others at following good research practice

- Amanda M. Lindkvist ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3984-5081 1 ,

- Lina Koppel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6302-0047 1 &

- Gustav Tinghög ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8159-1249 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 3050 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3519 Accesses

206 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Bounded ethicality refers to people’s limited capacity to consistently behave in line with their ethical standards. Here, we present results from a pre-registered, large-scale (N = 11,050) survey of researchers in Sweden, suggesting that researchers too are boundedly ethical. Specifically, researchers on average rated themselves as better than other researchers in their field at following good research practice, and rated researchers in their own field as better than researchers in other fields at following good research practice. These effects were stable across all academic fields, but strongest among researchers in the medical sciences. Taken together, our findings illustrate inflated self-righteous beliefs among researchers and research disciplines when it comes to research ethics, which may contribute to academic polarization and moral blindspots regarding one’s own and one’s colleagues’ use of questionable research practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Genome-wide association studies

Interviews in the social sciences

Introduction.

We would like to think that researchers are the pinnacle of objectivity and driven by purely scientific motives. However, researchers are also humans (surprise!) and restricted by the same cognitive boundaries and self-serving motivations as people in general. Over the past decade, there have been widespread discussions about the credibility of scientific claims due to a number of high-profile cases of scientific misconduct, low replication rates across several academic fields 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , and empirical evidence that the use of questionable research practices is surprisingly common 5 , 6 , 7 . To improve scientific research, we need to better understand the social and psychological mechanisms that contribute to the continued use of bad and questionable research practices. The need to explore how external and internal factors influence scientific activities was also recently highlighted in a call for the “psychology of science” 8 . Here, we investigate researchers’ beliefs about the extent to which they, and researchers in their field, follow good research practice, relative to other researchers. Our findings suggest that researchers on average hold inflated beliefs about their own research ethicality and the research ethicality of their field. In other words, researchers are not immune to ordinary psychological processes such as self-enhancement, which influence ethical decision-making.

People do not always behave ethically, even when they intend to do so. For example, we fail to help others in need 9 and overclaim credit for group work 10 . The concept of bounded ethicality has been used to explain these and other phenomena in which there is a gap between people’s intended and their actual ethical behavior 11 , 12 . Bounded ethicality refers to “the systematic and ordinary psychological processes of enhancing and protecting our ethical self-view, which automatically, dynamically, and cyclically influence the ethicality of decision-making” 12 . Specifically, according to Chugh and Kern’s 12 model of bounded ethicality, people are motivated to view themselves as ethical, and to uphold this self-view we engage in self-enhancement and self-protection. Which of these two processes are activated at a given time depends on the perceived level of self-threat. If self-threat is low, we engage in self-enhancement, by which we view our ethical behaviors as more ethical than they actually are and our unethical behaviors as less unethical than they actually are. For example, people tend to rate themselves as higher than others on a number of traits associated with being ethical 13 , 14 , to make overly positive predictions of how ethically they are likely to behave 15 , and to believe that their own moral behavior reflects something about themselves while their immoral behavior is due to circumstances 16 . Self-enhancement increases our positive self-view, but over time may lead to a slippery slope of increasingly unethical behavior as we fail to see the ethical implications of our own decisions.

The tendency to self-enhance and self-protect is also a defining feature of Homo Ignorans (“neglecting man”), which refers to humans’ choice to avoid, neglect, and distort information that poses a threat to one’s identity 17 , 18 . Enhancing and protecting one’s self-view can have benefits on an individual level, for example, by promoting and protecting one's confidence and self-esteem 19 . However, it can have harmful effects on a collective level, where it may lead to increased polarization between groups, escalating conflicts and undermining cooperation, whether in political, cultural, or academic contexts.

In this study, we investigate whether researchers exhibit a self-enhancing bias in their perceptions of the extent to which they follow good research practice. Specifically, we asked researchers to rate (a) the extent to which they follow good research practice compared to other researchers in their field, and (b) the extent to which researchers in their field follow good research practice compared to researchers in other fields. Given that people have a general tendency to rate themselves as better than others on favorable traits and skills 20 , 21 and strive to maintain an ethical self-view 11 , 12 , we predicted that researchers would rate themselves as following good research practice to a greater extent than other researchers in their field. This hypothesis is in line with results from surveys on research misbehavior and questionable research practices showing higher frequencies for observed behavior than for self-reported behaviors 7 .

We also predicted that researchers would rate researchers within their field as following good research practice to a greater extent than researchers in other fields. This hypothesis is in line with the idea that perceptions of in-group members are closely tied to self-perceptions—extending enhancement tendencies to individuals whom one is invested in 22 , 23 , 24 . In addition, individuals tend to exaggerate the relative importance of reaching the goals of one’s in-group over those of out-groups 25 . These exaggerations of goal importance are associated with the perception that one is justified to cut corners or behave unethically to reach those goals. In-group effects based on gender and seniority have previously been found among researchers, indicating a tendency to apply positive traits to other researchers who share one’s identity to a larger extent than to researchers from out-groups 26 . Here, we focus on shared identities based on academic discipline, which become established over time by learning the discipline-specific set of ways to think about and study the world. These discipline-based social identities strengthen over time by focusing on the similarities within fields and exaggerating the divides between them, resulting in academic silos 27 . Thus, researchers may view researchers in their field as more ethical than other researchers because they are highly identified with their discipline and strive to protect their identity as an (ethical) academic.

Materials and methods

Our methods, hypotheses, and data analysis plan were preregistered on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/f453z .

Sample and study design

The data were collected in a survey sent out to 33,290 Swedish researchers. The survey was distributed by the public agency Statistics Sweden. We used a total population sampling approach, inviting all individuals who met the following three criteria: 1) are registered in the Swedish population register, 2) have a PhD degree or are currently a PhD student, and 3) are hired at a Swedish university or higher learning facility. This last criterion only included state-funded educational institutions. Invitations to the study were sent out in September 2022 by postal mail and digital mailbox with a link to the web-based survey. Three reminders were sent out. Data collection was stopped in December 2022. Participants were able to view the survey in Swedish or English. In addition to the measures collected for the purposes of this study, the survey contained several different measures relating to ethical research behavior. To ensure readability, the survey underwent an initial pilot phase with a group of researchers who provided feedback. To further refine clarity, the survey underwent a metrological review by Statistics Sweden prior to the commencement of data collection.

In total 11,050 researchers responded, resulting in a response rate of 33.2%. Demographic and occupational variables were accessed from national registries and connected to individual survey responses by Statistics Sweden. Academic field included the 6 OECD categories: Natural sciences, Engineering and Technology, Medical and Health Sciences, Agricultural and Veterinary sciences, Social Sciences, and Humanities and the Arts. As specified in our preregistration, this variable was re-coded into a 4-level factor by including researchers from Engineering and Technology and Agricultural and Veterinary sciences as part of the broader category Natural sciences. Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample between genders, age, academic fields, and employment categories. The sample was close to representative of the sampling frame (i.e., the full population of researchers in Sweden) with regards to these variables, apart from slightly lower response frequencies for younger researchers and PhD students. Supplementary Table S1 shows response rates among different demographic and occupational characteristics.

After answering a series of questions about research ethics, respondents were presented with a description of good research practice taken from the Swedish Research Council 28 . The description outlined 8 general rules for good research practice: (1) To tell the truth about one’s research; (2) To consciously review and report the basic premises of one’s studies; (3) To openly account for one’s methods and results; (4) To openly account for one’s commercial interests and other associations; 5) To not make unauthorized use of the research results of others; (6) To keep one’s research organized, for example through documentation and filing; (7) Striving to conduct one’s research without doing harm to people, animals or the environment; and (8) To be fair in one’s judgement of others’ research. After reading this description, respondents were asked two questions: (1) In your role as a researcher, to what extent do you perceive yourself as following good research practices—compared to other researchers in your field? (2) To what extent do you perceive researchers within your field as following good research practices–compared to researchers within other fields? Each item was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = Much less than other researchers to 7 = Much more than other researchers , with 4 = As much as other researchers as the midpoint. The full survey is available on the OSF page for the overarching (parent) project ( https://osf.io/hw8zf/ ).

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using R 29 . Our main analyses consist of two-sided one-sample t-tests (coded as linear regressions) for each of the main measures, with the scale midpoint (i.e., 4) as the reference point. In addition, we ran linear regressions for each of the two main measures, predicting the difference between ratings and the midpoint of the scale by age and a binary coded gender variable. Confidence intervals for regression estimates were bootstrapped using the bootstrap percentile method with 10,000 replications, to address potential issues with non-normality. To illustrate potential differences in the effect between academic fields, we calculated effect sizes and confidence intervals for each field. All analyses specified in the pre-registration were followed without deviations or unreported exclusions. All respondents without missing data for the relevant analyses were included.

Ethics statement

We consulted the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and it was concluded that research of the kind that is conducted in this project is not covered by the Swedish Ethical Review Act (2003:460) and therefore ethical approval is not required. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants gave informed consent.

Do researchers rate themselves as following good practice more than others in their field?

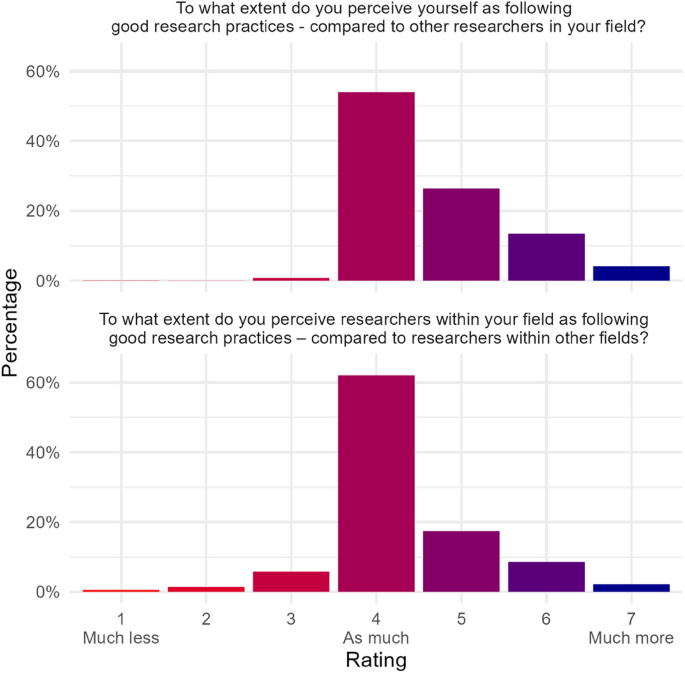

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the distribution of ratings when comparing oneself to other researchers in one’s field. Although many respondents (55%) rated themselves as following good research practice as much as their peers, practically no one (less than 1% of respondents) rated themselves as following good practice less than their peers. The remainder of the sample (about 44%) rated themselves as following good practice to a greater extent than other researchers in their field. On average, respondents rated themselves as 0.65 scale points higher than the scale midpoint, t (10,905) = 77.25, p < 0.001. This difference translates into an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.74, 95% CI = [0.70, 0.78]. The effect remained when controlling for age and gender ( B = 0.65, 95% bootstrapped CI = [0.58, 0.71], t (10,903) = 18.78, p < 0.001; see Table 2 for full regression output).

Distributions of ratings of research ethicality. Top panel: comparisons between oneself and researchers in one’s field, n = 10,906. Bottom panel: comparisons between researchers in one’s field and those in other fields, n = 10,816.

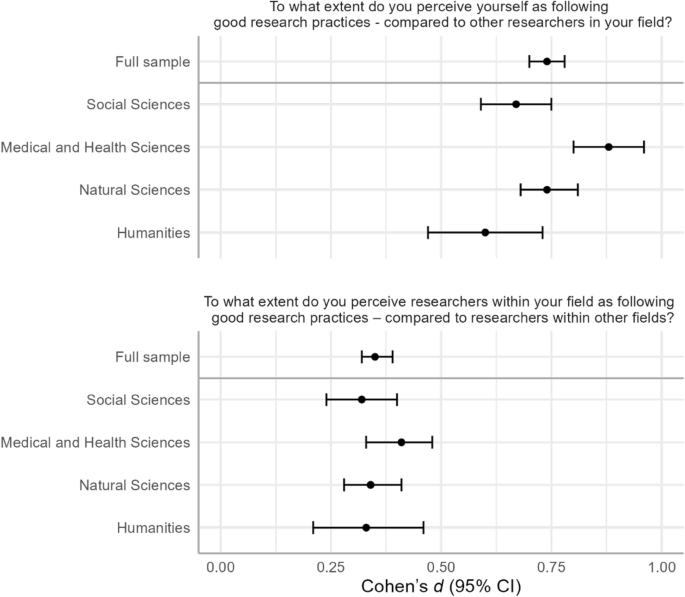

The effect was consistent across the four academic fields, varying from a Cohen’s d of 0.60 for respondents within Humanities and Arts to a d of 0.88 for respondents within Medical and Health sciences (see Fig. 2 , top panel). Exploratory analyses of effect sizes at the second level categorization of academic fields showed that all 38 subfields showed a positive effect in the range between Cohen’s d 0.50–0.94 (see Supplementary Fig. S2 ). Note, however, that for 2 of 38 subfields the 95% confidence intervals for d crossed 0. Only academic subfields with 30 or more respondents were included into these analyses.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d ) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the full sample and divided by academic field. Top panel: comparisons between oneself and researchers in one’s field. Bottom panel: comparisons between researchers in one's field and in other fields.

Do researchers rate researchers in their own field as following good practice more than researchers in other fields?

The bottom panel of Fig. 1 shows the distribution of ratings when comparing researchers in one’s field to researchers in other fields. Again, many respondents (63%) rated researchers in their field as following good practice as much as researchers in other fields, but only a small proportion (about 8% of respondents) rated researchers in their field as following good practice less than researchers in other fields. The remainder of the sample (29%) rated their field as following good practice more than other fields. The overall mean rating was 0.31 scale points higher than the scale midpoint, t (10,815) = 36.76, p < 0.001, d = 0.35, 95% CI = [0.32, 0.39]. The effect remained but was slightly smaller when controlling for age and gender in a linear regression model ( B = 0.24, 95% bootstrapped CI = [0.17, 0.31], t (10,813) = 6.87, p < 0.001; see Table 2 ). The change is explained by females on average giving slightly higher ratings than males ( B = 0.06, 95% bootstrapped CI = [0.02, 0.09], t (10,813) = 3.27, p = 0.001). Age was not a statistically significant predictor.

The effect was consistent across the four academic fields, varying between a Cohen’s d of 0.32 for respondents in the Social sciences to a d of 0.41 for respondents in the Medical and Health sciences (see Fig. 2 , bottom panel). Exploratory analyses of effect sizes at the second level categorization of academic fields showed a large degree of variation. While all of the 38 subfields (with 30 or more respondents) showed a positive Cohen’s d , the effect size ranged between 0.07 and 0.74 (see Supplementary Fig. S4 ) and for 16/38 subfields the 95% confidence intervals crossed zero.

As exploratory analyses we also preregistered correlational analysis between ratings of oneself (vs. one's field) and ratings of one's field (vs. other fields), which showed a positive correlation of r (10,793) = 0.14, p < 001.

We conducted a large-scale survey of 11,050 researchers and found that researchers on average rated themselves as better than other researchers at following good research practice, and rated researchers in their field as better than researchers in other fields at following good research practice. Given that it is statistically impossible for the majority of a group to be better than the group median, our results suggest that researchers on average have inflated beliefs about their own research ethicality and the research ethicality of their field. It is worth noting that many respondents rated themselves as following good research practice as much as their peers, thus not self-enhancing relative to others; but the effect we observed occurred on the aggregate level. Importantly, the effect was consistent across all academic fields, although researchers working within Medical and Health Sciences displayed the largest effects both for perceptions about themselves and for perceptions about researchers within their field. Our findings add to the existing literature on the prevalence and predictors of questionable research practices 5 , 6 , 7 , by suggesting that researchers are not immune to ordinary psychological processes such as self-enhancement, which influence the ethicality of decision-making.

According to Chugh and Kern’s 12 model of bounded ethicality, self-enhancement contributes to the maintenance of an ethical self-view but leads to increasingly unethical behavior over time. Thus, one could speculate that inflated beliefs about one’s research ethicality may lead researchers to underestimate the ethical implications of the decisions they make and to sometimes be blind to their own ethical failures. For example, researchers may downplay their own questionable practices but exaggerate those of other researchers, perhaps especially researchers outside their field. Such distortion of information may be comfortable on an individual level in that it protects one’s (academic) identity, but on a collective level it may contribute to increased academic polarization that hinders constructive discourse, collaboration, and the pursuit of shared knowledge between researchers and academic disciplines. Thus, the finding that inflated beliefs extend to one’s academic discipline could help explain why interdisciplinary collaboration is so difficult to maintain. In addition, self-enhancement may be especially likely to lead to less ethical behavior among researchers who win the “academic game”. That is, researchers who believe they are superior to others in terms of research ethicality may be especially likely to engage in questionable research practices (because they may not see the ethical implications of their behaviors), and these practices are positively reinforced for researchers who also succeed in their career (e.g., who get tenure, publish in prestigious journals, etc.). Furthermore, if we believe ourselves to be more ethical than others in terms of our research practices, then we are less likely to pay attention to information and guidelines aimed at counteracting questionable research practices, because such information and guidelines will appear to be directed to someone else and not to ourselves.

How can people’s inflated ethical self-views be “de-biased” and ethical behavior be increased? According to Chugh and Kern's model of bounded ethicality, people continue to engage in self-enhancement as long as the perceived threat to one’s ethical self-view is low 12 . However, if the perceived self-threat is high, people will engage in self-protective processes, leading them to either behave more ethically (a primary control mechanism) or continue to behave unethically but reframe or justify the behavior (e.g., by placing the responsibility for any negative consequences of the unethical behavior in someone else’s hands; a secondary control mechanism). Thus, one way to increase ethical behavior is to ”nudge” people out of self-enhancement and into self-protection, and, once there, to increase people’s moral awareness (to activate primary rather than secondary control mechanisms). In the context of scientific research, several measures have been proposed (and to some degree implemented) to increase researchers’ moral awareness. These include, for example, affirmative disclosure statements for conflicts of interest 30 and for methodological practices 31 . Moreover, pre-registration of hypotheses and analysis plans can be one way to constrain researchers' ethical degrees of freedom in a research climate that incentivizes researchers to cut corners to achieve academic success. Overall, structural and cultural changes leading to increased transparency of research practices ought to increase self-threat and, by extension, ethical research behavior.

As with any study, some limitations are warranted. Firstly, although the survey was distributed to all researchers in Sweden via a government agency, we cannot rule out the possibility of self-selection bias. One could speculate that those who chose not to respond might be more likely to rate themselves below average in research ethicality, resulting in an overestimation of the true effect size in the present study. On the other hand, it seems less likely that such self-selection bias would influence ratings of one’s field compared to other fields. Secondly, although the better-than-average effect has been demonstrated in a variety of contexts and is a well-replicated finding 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , it is difficult to extrapolate to what extent responses on the types of scales used in this literature reflect overconfidence or self-serving bias. Benoît and Dubra 36 argue that a population of completely rational individuals—who accurately update their beliefs in the light of available information—can display beliefs that can be (mis)interpreted as overconfidence or underconfidence. In particular, studies of better-than-average effects rarely ask about the strength of people’s beliefs, which complicates the interpretation of results. Better-than-average effects also tend to be larger for positive (vs. negative) attributes and when using the direct method (by which participants rate themselves compared to an average other on one single response scale) compared to the indirect method (by which participants rate themselves and the average other on two separate scales 34 ;). Hence, it is an open question whether we would obtain effects of the same magnitude if we asked about engagement in un ethical research practices, relative to others.

The spotlight of the ongoing credibility crisis in science is often on the extreme and clear-cut cases of research misconduct. However, there is a more pressing concern that goes beyond high-profile incidents of research fraud and data fabrication. It pertains to the "everyday" questionable research practices—instances where researchers who want to uphold research ethical principles breach those same principles, often without being aware of it. The current study speaks to this issue. John et al. 6 refer to questionable research practices as “ the steroids of scientific competition” . In a world where questionable research practices inadvertently are rewarded, researchers who strictly play by the rules find themselves at a disadvantage. On an everyday basis, researchers are faced with the dilemma of whether they should do what is best for themselves and their career or what is best for scientific progress. Therefore, research ethics should not primarily be about pointing fingers at others, but about looking at oneself in the mirror. We are all boundedly ethical researchers who sometimes breach our own research ethical standards. To restore science’s credibility, we need to create incentive structures, institutions, and communities that foster ethical humility and encourage us to be our most ethical selves in an academic system that otherwise incentivizes us to be bad.

Data availability

Data for this study are openly accessible at https://osf.io/ku9nd/ .

Code availability

All analysis code needed to reproduce the study’s main analyses are publicly available on the project’s OSF repository ( https://osf.io/ku9nd/ ). In addition, the uploaded HTML-document includes output, packages, and package versions.

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating replicability of laboratory experiments in economics. Science 351 , 1433–1436 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2 , 637–644 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Errington, T. M. et al. Investigating the replicability of preclinical cancer biology. eLife 10 , e71601 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Open Science Collaboration. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 , 4716 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Gopalakrishna, G. et al. Prevalence of questionable research practices, research misconduct and their potential explanatory factors: A survey among academic researchers in The Netherlands. PLOS ONE 17 , e0263023 (2022).

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G. & Prelec, D. Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 524–532 (2012).

Xie, Y., Wang, K. & Kong, Y. Prevalence of research misconduct and questionable research practices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Eng. Ethics 27 , 41 (2021).

Aczel, B. Why we need a ‘psychology of science’. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8 , 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01786-4 (2024).

Darley, J. M. & Latane, B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 8 , 377–383 (1968).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Caruso, E. M., Epley, N. & Bazerman, M. H. The costs and benefits of undoing egocentric responsibility assessments in groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91 , 857–871 (2006).

Chugh, D., Bazerman, M. H. & Banaji, M. R. Bounded Ethicality as a Psychological Barrier to Recognizing Conflicts of Interest. in Conflicts of Interest (eds. Moore, D. A., Cain, D. M., Loewenstein, G. & Bazerman, M. H.) 74–95 (Cambridge University Press, 2005). doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511610332.006 .

Chugh, D. & Kern, M. C. A dynamic and cyclical model of bounded ethicality. Res. Organ. Behav. 36 , 85–100 (2016).

Google Scholar

Tappin, B. M. & McKay, R. T. The illusion of moral superiority. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8 , 623–631 (2017).

Tenbrunsel, A. E. Misrepresentation and expectations of misrepresentation in an ethical dilemma: The role of incentives and temptation. Acad. Manage. J. 41 , 330–339 (1998).

Epley, N. & Dunning, D. Feeling ‘holier than thou’: Are self-serving assessments produced by errors in self- or social prediction?. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79 , 861–875 (2000).

Han, K. & Kim, M. Y. Mechanism of the better-than-average effect in moral issues: Asymmetrical causal attribution across moral (vs. immoral) contexts. Acta Psychol. 226 , 103575 (2022).

Tinghög, G., Barrafrem, K. & Västfjäll, D. The good, bad and ugly of information (un)processing; Homo economicus, homo heuristicus and homo ignorans. J. Econ. Psychol. 94 , 102574 (2023).

Hertwig, R. & Engel, C. Homo ignorans: Deliberately choosing not to know. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 , 359–372 (2016).

Loewenstein, G. & Molnar, A. The renaissance of belief-based utility in economics. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2 , 166–167 (2018).

Alicke, M. D. & Govorun, O. The Better-Than-Average Effect. in The Self in Social Judgment (eds. Alicke, M. D., Dunning, D. A. & Krueger, J.) 85–106 (Psychology Press, 2005).

Svenson, O. Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers?. Acta Psychol. 47 , 143–148 (1981).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Alicke, M. D., Klotz, M. L., Breitenbecher, D. L., Yurak, T. J. & Vredenburg, D. S. Personal contact, individuation, and the better-than-average effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68 , 804–825 (1995).

Alicke, M. D. & Sedikides, C. Self-enhancement and self-protection: Historical overview and conceptual framework. in Handbook of Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection (eds. Alicke, M. D. & Sedikides, C.) 1–19 (Guilford Press, 2010).

Perloff, L. S. & Fetzer, B. K. Self–other judgments and perceived vulnerability to victimization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 50 , 502–510 (1986).

Hoyt, C. L., Price, T. L. & Emrick, A. E. Leadership and the more-important-than-average effect: Overestimation of group goals and the justification of unethical behavior. Leadership 6 , 391–407 (2010).

Veldkamp, C. L. S., Hartgerink, C. H. J., Van Assen, M. A. L. M. & Wicherts, J. M. Who believes in the storybook image of the scientist?. Account. Res. 24 , 127–151 (2017).

Poole, G. Academic Disciplines: Homes or Barricades? in The University and its Disciplines: Teaching and Learning Within and Beyond Disciplinary Boundaries (ed. Kreber, C.) 74–81 (Routledge, 2009).

Swedish Research Council. Good research practice. (2017).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2022).

Dana, J., Loewenstein, G. & Weber, R. Ethical immunity: How people violate their own moral standards without feeling they are doing so. in Behavioral Business Ethics: Shaping an Emerging Field (eds. De Cremer, D. & Tenbrunsel, A. E.) 197–214 (Routledge, 2011).

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D. & Simonsohn, U. A 21 word solution. SSRN Scholarly Paper at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2160588 (2012).

Koppel, L., Andersson, D., Tinghög, G., Västfjäll, D. & Feldman, G. We are all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers: Successful replication and extension of Svenson (1981). Meta-Psychol. 7 , (2023).

Korbmacher, M., Kwan, C. & Feldman, G. Both better and worse than others depending on difficulty: Replication and extensions of Kruger’s (1999) above and below average effects. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 17 , 449–486 (2022).

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C. & Alicke, M. D. The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146 , 118–149 (2020).

Ziano, I., Mok, P. Y. & Feldman, G. Replication and extension of Alicke (1985) better-than-average effect for desirable and controllable traits. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12 , 1005–1017 (2021).

Benoît, J.-P. & Dubra, J. Apparent overconfidence. Econometrica 79 , 1591–1625 (2011).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Erika Bergentz at Statistics Sweden for help during the data collection. Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Management and Engineering, Division of Economics, Linköping University, 581 83, Linköping, Sweden

Amanda M. Lindkvist, Lina Koppel & Gustav Tinghög

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.L., L.K., and G.T. designed the study together. A.L analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript together with L.K. and G.T. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gustav Tinghög .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

All authors declare no conflicting interests that could have appeared to influence the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lindkvist, A.M., Koppel, L. & Tinghög, G. Bounded research ethicality: researchers rate themselves and their field as better than others at following good research practice. Sci Rep 14 , 3050 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53450-0

Download citation

Received : 20 November 2023

Accepted : 31 January 2024

Published : 06 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53450-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 17 February 2020

Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour

- Jean Gabriel Guerrero-Dib ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3150-9363 1 ,

- Luis Portales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1508-7826 1 &

- Yolanda Heredia-Escorza ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7300-1918 2

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 16 , Article number: 2 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

76k Accesses

59 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Corruption is a serious problem in Mexico and the available information regarding the levels of academic dishonesty in Mexico is not very encouraging. Academic integrity is essential in any teaching-learning process focussed on achieving the highest standards of excellence and learning. Promoting and experiencing academic integrity within the university context has a twofold purpose: to achieve the necessary learnings and skills to appropriately perform a specific profession and to develop an ethical perspective which leads to correct decision making. The objective of this study is to explore the relationship between academic integrity and ethical behaviour, particularly workplace behaviour. The study adopts a quantitative, hypothetical and deductive approach. A questionnaire was applied to 1203 college students to gather information regarding the frequency in which they undertake acts of dishonesty in different environments and in regards to the severity they assign to each type of infraction. The results reflect that students who report committing acts against academic integrity also report being involved in dishonest activities in other contexts, and that students who consider academic breaches less serious, report being engaged in academic misconduct more frequently in different contexts. In view of these results, it is unavoidable to reflect on the role that educational institutions and businesses can adopt in the development of programmes to promote a culture of academic integrity which: design educational experiences to foster learning, better prepare students to fully meet their academic obligations, highlight the benefits of doing so, prevent the severity and consequences of dishonest actions, discourage cheating and establish clear and efficient processes to sanction those students who are found responsible for academic breaches.

Introduction

Corruption and dishonesty are deeply rooted problems and have a long history in many countries and communities and Mexico is no exception. There is usually more attention given to corrupt activities perpetrated by government authorities and public officers. The fact that many of these instances of corruption are carried out with the collusion of private sector businesses and individuals is largely ignored. Private citizens themselves are usually involved in corrupt activities where they can gain a personal benefit through the abuse of their position of power or authority (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka 2016 ).

Rose-Ackerman and Palifka ( 2016 ) affirm that personal ethical standards are one of the three categories of causes that promote corruption. This moral “compass” develops through a long and complex educational process which starts at home and, we could say, ends with death. Education becomes one of the key elements in the global strategy for the promotion of a culture of integrity and the fight against corruption. It is difficult to think that education can contribute efficiently if the phenomenon of academic dishonesty exists within the educational sphere. To develop a moral compass, it is not enough to know what has to be done, it is essential to do good (Amilburu 2005 ).

In almost every educational system in the world, it is a widely held view that all people must receive mandatory basic education, thus, almost all children and youths are subject to experience -or not experience- academic integrity during their education, a period that is long enough to develop habits. Daily behaviours during these mainly formative years may be considered as the standard that can perpetuate itself over time (Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo 2015 ).

In addition to the work carried out by the basic educational system, the university must fully form and develop the moral vision and purpose of its students, since it is not possible to consider professional education separate from ethical formation. Being a professional must include not only mastery of technical, practical and/or theoretical competencies, but also personal integrity and ethical professional behaviour that helps to give an ethical meaning to all university endeavours (Bolívar 2005 ). In so doing, academic integrity is necessary to learn and an essential requirement of academic quality.

Academic integrity is much more than avoiding dishonest practices such as copying during exams, plagiarizing or contract cheating; it implies an engagement with learning and work which is well done, complete, and focused on a good purpose – learning. It also involves using appropriate means, genuine effort and good skills. Mainly it implies diligently taking advantage of all learning experiences. From this perspective, experiencing and promoting academic integrity in the university context has a twofold purpose: achieving the learning intended to develop the necessary competencies and skills for a specific profession and, more importantly, developing an ethical perspective for principled decision making applicable to any context (Bolívar 2005 ).

Orosz et al. ( 2018 ) identified a strong relationship between academic dishonesty and the level of corruption of a country. Other studies (Blankenship and Whitley 2000 ; Harding et al. 2004 ; Laduke 2013 ; Nonis and Swift 2001 ; Sims 1993 ) demonstrate that students who engage in dishonest activities in the academic context, particularly undergraduate students, are more likely to demonstrate inappropriate behaviours during their professional life and vice versa.

From this point of view one can say that: the individual who is used to cheating in college, has a higher probability of doing so in the professional and work fields (Harding et al. 2004 ; Payan et al. 2010 ; Sims 1993 ).

Taking these studies in other parts of the world as a reference, the objective of the current work is to determine the relationship between the most frequent academic dishonesty practices, or lack of academic integrity amongst college students, and their predisposition to demonstrate ethical behaviour at work and in their daily lives within the Mexican context.

This research paper is divided into four sections. The first one presents a brief review of literature on academic integrity, academic dishonesty and its relationship with workplace ethical behaviour. The second section presents the methodology followed during the study, considering the design and validation of the instrument, data gathering, and the generation of academic dishonesty and ethical behaviour indexes. The third section shows the results of the analysis and its discussion. The last section displays a series of conclusions for the research presented, as well as its limitations and scope.

Literature review

- Academic integrity

According to Bosch and Cavallotti ( 2016 ), the term integrity has four common elements that are included in the different ways to describe it: justice, coherence, ethical principles and appropriate motivation. Thus, a definition in accordance to this concept would be to act with justice and coherence, following ethical principles and a motivation focused on good purposes. In the educational context, academic integrity could be understood as the habit of studying and carrying out academic work with justice and coherence, seeking to learn and to be motivated by the service that this learning can provide others. However, there has been a wide variety of interpretations about this concept (Fishman 2016 ).

The International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI), conceptualizes academic integrity as a series of basic principles which are the foundation for success in any aspect of life and represent essential elements that allow achievement of the necessary learning which enable the future student to face and overcome any personal and professional challenges (International Center for Academic Integrity 2014 ).

Academic integrity is considered a fundamental quality for every academic endeavour, essential in any teaching-learning process focused on achieving the highest standards of excellence and learning and thus, it must represent a goal to which every academic institution, seriously engaged in quality, must aspire to (Bertram-Gallant 2016 ). Enacting academic integrity means taking action with responsibility, honesty, respect, trust, fairness, and courage in any activity related to academic work and avoiding any kind of cheating or dishonest action even when the work is especially difficult (International Center for Academic Integrity 2014 ).

The current approaches to academic integrity provide ideas offering a conceptual framework, but there is still the need to specify concrete academic integrity behaviours characteristic of students such as: speaking the truth, complying with classes and assignments, carrying out activities by their own efforts, following the instructions given, providing answers on exams with only the material approved, citing and giving credit to others’ work, and collaborating fairly during teamwork assignments (Hall and Kuh 1998 ; Von Dran et al. 2001 ). To these “observable” behaviours we must add a condition: that they must be preceded by the desire to learn in order to call them genuine manifestations of academic integrity (Olt 2002 ; Sultana 2018 ).

Despite the importance of the academic integrity concept, in most cases it is common to find an explanation of the concept in more negative terms that refers to behaviours that should be avoided. The general idea expressed in most honor codes is that academic integrity is to do academic work avoiding dishonesty, fraud or misconduct.

Dishonesty and academic fraud

Stephens ( 2016 ) argues that the problem of cheating is endemic and is at the root of human nature, thus it should not be surprising that it occurs. It is a strategy, conscious or not, used by humans to solve a problem. However, recognizing that cheating has always existed should not foster a passive and pessimistic attitude since human beings have a conscience that enables them to discern ethical behaviours from those that are not.

Understanding the phenomenon of dishonesty is important since the strategies used to try to counteract it will depend on this. For example, if dishonesty is considered a genetic disorder that some people suffer, the way to deal with it would be to identify those who suffer from it, supervise them, segregate them and/or try to “treat” them. If it is a common deficiency that everyone experiences to a greater or smaller degree, other kinds of tactics should be used to counteract it (Ariely 2013 ).

In general terms, there are different types of academic dishonesty that may be grouped into four major categories:

Copying. Copying or attempting to copy from a classmate during an examination or assessment.

Plagiarism. Copying, paraphrasing or using another author’s ideas without citing or giving the corresponding credit to them.

Collusion. Collaboration with someone else’s dishonesty, and includes not reporting dishonest actions which have been witnessed. The most representative actions of this type of misconduct are: submitting assignments on behalf of classmates, allowing others to copy from you during an exam and including the names of people who did not participate in teamwork assignments or projects.

Cheating. Among the most common actions in this category we find: using notes, technology or other forbidden materials during an exam; including non-consulted references; inventing or making up data in assignments or lab reports; contract cheating; distributing or commercializing exams or assignments; submitting apocryphal documents; impersonating another student’s identity; stealing exams; altering grades; bribing individuals to improve grades.

The list is not exhaustive since it does not include every possible type of dishonesty. Every situation creates unique circumstances and different nuances so it should not be surprising that the emergence of “new” ways to threaten academic integrity arise (Bertram-Gallant 2016 ). Students’ creativity and the continual development of technology will cause different manifestations of academic fraud (Gino and Ariely 2012 ), a fact that has been documented in university contexts in the past.

The results of recent research show that 66% of students have engaged in some type of academic misconduct at least once during their university education (Lang 2013 ). There are similar results in other studies carried out around the world. In the Mexican case, 84% of students in a Mexican university have witnessed a dishonest action during their education (UDEM 2018 ), and 6 out of 10 at another university have engaged in some kind of copying (UNAM 2013 ). In Colombia, a private university reported that 63% of the students accepted the addition of the name of a classmate that did not collaborate actively on a team assignment (EAFIT 2016 ). In England, half of the students would be willing to buy an assignment (Rigby et al. 2015 ). In Ukraine, 82% of students have used non-authorized support during exams (Stephens et al. 2010 ). While in China, 71% of students at one university admit to having copied a homework assignment from his/her classmates (Ma et al. 2013 ).

Academic dishonesty and its relationship with the lack of ethical professional behaviour

Establishing a relationship between the level of corruption in a country and the level of academic dishonesty in its educational institutions is a difficult task to carry out since fraud and corruption have many different forms and causes, particularly in complex contexts such as the social dynamics of a country (International Transparency 2017 ). However, it can be established that academic dishonesty is a manifestation of a culture in which it is easy and common to break rules and where integrity is not as valued as it should be. Under this logic, it is possible to establish a certain relationship between a poor civic culture and academic dishonesty (García-Villegas et al. 2016 ).

This poor civic culture tends to be reflected in the daily activities of the citizens, particularly within organizations, where a relationship between students who cheat and unethical behaviour in the workplace has been identified (Winrow 2015 ). From this point of view, integrity and ethical behaviour, expressed in different terms such as decision making, conflict resolution or accountability, is one of the competencies most requested by employers (Kavanagh and Drennan 2008 ) and one of the critical factors needed to efficiently develop inter-organizational relationships of trust (Connelly et al. 2018 ). This is the reason behind the study, the understanding of this relationship.

A study carried out with 1051 students from six North American universities concluded that students who considered academic dishonesty as acceptable tended to engage in such activities and the same individuals tended to show unethical behaviour later during their professional lives (Nonis and Swift 2001 ). In another study with Engineering students, it was found that those who self-reported having engaged in dishonest actions, also carried it out in the professional field, which suggests that unethical behaviour shown at the college level continued into professional life (Harding et al. 2004 ). Findings of another study carried out at a nursing school demonstrated that students who showed academic dishonesty had a greater incidence of dishonest behaviour once they worked as health professionals (Laduke 2013 ).

In a study carried out with 284 psychology students who reported having engaged in some kind of academic dishonesty, specifically having copied during exams and lying in order to meet their obligations during their college education, also reported participating in actions considered illegal or unethical within the context of the research, specifically those related to substance abuse - alcohol and drugs, risky driving, lying and other sort of illegal behaviours. This data suggests that, besides the contextual factors, there are also individual causes such as attitudes, perceptions and personality traits that can influence the individual’s behaviour in different aspects of their lives (Blankenship and Whitley 2000 ).

In one of the most recent studies, where data from 40 countries was collected, a strong relationship was identified between the self-reporting “copying in exams” of the student population and the level of corruption of the country, expressed in the corruption perception index published by Transparency International (Orosz et al. 2018 ).

Despite the increase in the number of studies related to academic integrity and ethical behaviour in the companies in different parts of the world since the 1990s, it has not been possible to identify any research in Mexico that explores the relationship between the ethical behaviour of an individual in his/her different life stages, as a college student and as a professional; or to put it differently, between academic integrity and ethical performance in the workplace.

Methodology

This study followed a quantitative approach under a hypothetic - deductive approach. Since there is no suitable instrument available that explores the relationship between academic integrity and ethical behaviour, one designed for this study was used. It was based on questions from previous research instruments.

The “International Center for Academic Integrity” (ICAI) perception survey, created by Donald McCabe and applied to more than 90,000 students in the United States and Canada (McCabe 2016 ) was adapted with the addition of a section of questions related to personal and workplace ethical behaviour.

The McCabe survey ( 2016 ) consists of 35 questions that can be grouped into four sections. The first one explores the characteristics of the academic integrity programme, the educational atmosphere in general and the way in which the community is informed and trained in regards to current regulations. The second one requests information about the students’ behaviour. It specifically asks about the frequency with which students are involved in dishonest activities at the moment and in previous academic levels, how severe they considered each kind of misconduct and their perception in regards to the level of peer participation in actions against integrity. The third section collects the opinions of the students regarding different statements related to academic work, faculty and students’ engagement in the development of an academic integrity culture, strategies to fight dishonesty, the degree of social approval towards academic fraud, its impact and the perception of fairness in managing the cases of misconduct. The last group included demographic questions that contained basic information about the person answering the survey. The students were asked to provide their age, gender, marital status, nationality, place of residence, accumulated grade point average (GPA), programme he/she studies and the number of years at the university.

A section was added to this survey (Additional file 1 ) addressing the professional ethical behavioural construct. In this section, items from questionnaires described in Table 1 were used; all related to self-reporting of ethical behaviour. An additional validation was carried out for this instrument section through the assessment of experts from the internal control area of different companies and industries.

Except for a couple of open questions, the rest of the items used responses built under a five-point Likert scale to categorize their judgments in regards to the statements suggested. There are two types of responses used specifically: from totally agree to totally disagree about the perceptions and opinions; and always or never in the case of self-reported behaviours.

The responses were recorded automatically in the data base of the SurveyMonkey technology tool and values were assigned to each one of the responses in order to calculate an index per response, assigning a value of 5 to “Totally agree” and 1 to “Totally disagree” in a positive or favorable statement, and vice-versa, 1 and 5 respectively, in a negative or unfavorable statement.

The sample considers 1203 undergraduate and graduate students from a private university in northern Mexico who chose to respond to their professors’ invitations to answer the survey as part of a diagnostic exercise that the university carries out periodically to learn about the students’ perceptions regarding the degree of academic integrity culture on their campus. The participants were 51% women and 49% men. From them, 31% were in their first year, 25% the second year, 26% the third year, 11% the fourth year and only 7% had been studying for five or more years. Nearly 70% of the students still lived in their parents’ homes and 42% reported having a good or outstanding average grade (higher than 80 over 100).

Once the data was collected, the internal validation of the instrument was done and indexes were generated for each one of the variables introduced into the model, through a factorial analysis of the main components. This type of analysis studies the relationship between a set of indicators or variables observed and one or more factors related to the research to obtain evidence and thus, validate the theoretical model (Hayton et al. 2004 ).

In order to define the indexes related to academic fraud and ethical behaviour there were three factorial analyses carried out, which took as selection criteria eigenvalues higher than one and varimax component rotation with the purpose to maximize the variances explained for each response and identify the items that represented the factors identified by the analysis itself in a linear way (Thompson 2004 ).

The first analysis considered questions related to the level of frequency with which specific dishonest actions were carried out. It included 27 items or questions in total, and five components accounted for 66.33% of the variance, with a KMO (Kaiser, Meyer and Olkin) of 0.955 and being significant for the Bartlett’s sphericity test, a fact that shows the internal consistency of the indicator and its statistical validity. The five components were classified according to the weight that each question had in the rotated and stored components matrix such as regression variables to generate an indicator for each of them (Table 5 in Appendix). These indicators were defined as frequency in: 1) cheating in general, 2) copying in any way, 3) falsifying information, 4) using unauthorized support, and 5) plagiarizing or paraphrasing without citing.

The second analysis took the same criteria of the latter, but it only included the 27 questions related to how severe the misconduct or academic dishonesty was considered. The result was three components that accounted for 67.66% of the variance observed, with a KMO of 0.962 and the Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant. The rotated components were classified and kept as a regression to generate three indicators, related to the perceived severity of: 1) cheating in general, 2) plagiarizing or copying and paraphrasing without citing, and 3) using unauthorized support (Table 6 in Appendix ).

The third factorial analysis included the 47 questions related to the behaviour or ethical attitude of the respondents. This analysis generated six components that accounted for 64.54% of the variance observed, a KMO of 0.963 and the Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant. When analyzing the components generated by the analysis, it was observed that four of them had only two questions with a weight greater than 0.4 in the rotated component matrix. Considering this situation, it was decided to eliminate these questions and a new factorial analysis was carried out considering only 39 questions. The result was two main components that accounted for 58.66% of the variance observed, with a KMO of 0.965 and the Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant. The two components were classified into two indicators: 1) workplace ethical behaviour and, 2) personal ethical behaviour (Table 7 in Appendix ).

Once the indicators for frequency and perceived severity of dishonesty or academic fraud, as well as those related to the behaviour or self-reported ethical attitude (workplace and personal) were generated, a linear regression analysis was carried out to determine how academic dishonesty influences a specific ethical behaviour.

The linear regression analysis took as dependent variables the ones related to ethical behaviour self-reported by the respondents, and the frequency and severity of the academic dishonesty acts reported by the respondents as the independent variables. This analysis was carried out in two stages; the first one considered only the variable of the frequency with which academic dishonesty was reported, and the second one considered the variables related to the severity with which the respondents perceived these actions.

The first analysis took as independent variables the frequency of each component of self-reported academic misconduct: cheating in general, copying in any way, falsifying information, using unauthorized support, and plagiarizing or paraphrasing without citing. The result of the model was significant for the case of workplace ethical behaviour (sig. = 0.001), accounting for only 3.4% of the variance observed (Table 2 ). In terms of analysis by variables, it was found that only the frequency of carrying out any kind of cheating, and copying in any way, had a significant impact on the workplace ethical behaviour of the respondents. The negative coefficient in both cases shows that a frequency reduction in academic misconduct, increased the self-reported workplace ethical behaviour (Table 2 ). The variables for falsifying information, using unauthorized support and plagiarizing didn’t show significance.

In terms of personal ethical behaviour, the model proved significant (sig. = 0.000) explaining 9% of the variance (Table 2 ) thus it may be stated that the severity of academic dishonesty influences personal ethical behaviour. In regards to the impact level that the variables have on personal ethical behaviour, we found that only using unauthorized support did not prove significant. The remaining variables were significant and with negative coefficients, thus we may conclude that the lower the frequency of academic dishonesty reported by the respondents, the higher the reported personal ethical behaviour. In this sense, the variable of cheating in general had a greater weight in this kind of behaviour, followed by falsifying information and lastly plagiarizing.