- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Best Biographies » The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

Twilight of democracy, by anne applebaum.

Anne Applebaum’s latest book, Twilight of Democracy, is part polemic, part memoir, and tracks how and why so many people she knew (eg Viktor Orban, who has been prime minister of Hungary for the past decade) abandoned liberal democracy and became far right populists. Applebaum was a foreign correspondent in eastern Europe at the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall and continued to cover the region for many years.

We interviewed Anne Applebaum on the best Memoirs of Communism.

Five Books review

Anne Applebaum has been well plugged in on the centre right of European and American politics for over 30 years. This book—part polemic, part memoir (subtitled outside the US ‘The Failure of Politics and the Parting of Friends’)—is an insider’s view of how the political right in Applebaum’s native US, but also in the other countries Applebaum knows well—particularly Poland, Hungary and the UK—has split. In the 1990s everyone on the centre right championed free markets, free trade, democracy and the rule of law. Some, like Applebaum, still cling to the liberal, internationalist visions of the 1990s. But the book largely seeks to explain why a lot of her friends in all these countries ended up rejecting the liberal order they used to champion in the 1990s turning, instead, to various forms of populism, authoritarianism, social conservatism, tribalism and protectionism. Applebaum knew Viktor Orban, the prime minister of Hungary, in his liberal days, she used to be friends with people who now work for Trump . She was once friends with Boris Johnson and other leading Brexiteers . Now they don’t see each other and huge chasms have opened up between them politically. By tracing the political development of her old friends over the past 20-odd years, Applebaum tries to find the reasons why her old allies in Poland and Hungary advocate ‘managed democracy’ and seek to undermine judicial independence and freedom of the press, while in the US they entertain conspiracy theories and, in the UK, retreat into undeliverable and nostalgic dreams of national influence. A thoughtful contribution to the debate about what’s gone wrong with politics in the ‘free world’.

Recommendations from our site

“Applebaum demonstrates that the trend against democracy is worldwide and difficult to reverse. And Applebaum outlines the reason why human beings all across the world have moved toward authoritarianism in troubled times. Authoritarians promise easy and absolute solutions. They say they will make the trains run on time then insist the clocks are lying when they’re late.” Read more...

The Best Politics Books To Read in 2021

Larry Sabato

“Although, at this point, there are many books about the attacks on democracy, Anne Applebaum’s stands apart both because she’s a particularly gifted storyteller and because she draws from her personal experience. The book starts with a New Year’s Eve party she organized at the start of this millennium at her countryside home in Poland. She chronicles how half of the people who attended went on to defend democratic institutions and the other half became leading members of the Polish populist regime and its media allies.” Read more...

The Best Politics Books of 2020

Yascha Mounk , Political Scientist

“In the United States, United Kingdom, India, Brazil—around the world leaders have got into power by offering xenophobic, nationalistic messages. Why? Anne Applebaum’s book is her personal experience of this trend, as an American journalist and author who has spent a lot of time in Poland (amongst other places). What’s fascinating is how a random event, a plane crash that killed the Polish prime minister Lech Kaczyński in 2010, seems to have been the trigger for the craziness and conspiracy theories that have followed, some of which have targeted Applebaum herself. In the UK, it was Brexit, and, again, there’s a personal connection. Applebaum knows the British prime minister Boris Johnson, because her husband was a contemporary of his at Oxford (they were both members of the Bullingdon, an all-male dining club). Applebaum chronicles how Johnson basically got into the EU-bashing because it went down well when he was a journalist in Brussels and has continued to pursue it haphazardly ever since for opportunistic reasons. There’s a lot to think about after reading this book, and it doesn’t offer any easy answers.” Read more...

The Best Nonfiction Books of 2020

Sophie Roell , Journalist

Other books by Anne Applebaum

Red famine: stalin's war on ukraine by anne applebaum, iron curtain: the crushing of eastern europe 1944-56 by anne applebaum, gulag: a history by anne applebaum, between east and west by anne applebaum, our most recommended books, speak, memory by vladimir nabokov, harare north by brian chikwava, up in the old hotel by joseph mitchell, surprised by joy: the shape of my early life by c s lewis, golem girl: a memoir by riva lehrer, the collected schizophrenias: essays by esmé weijun wang.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce, please support us by donating a small amount .

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism

A Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and journalist explains, with electrifying clarity, why some of her contemporaries have abandoned liberal democratic ideals in favor of strongman cults, nationalist movements, or one-party states.

Across the world today, from the US to Europe and beyond, liberal democracy is under siege while different forms of authoritarianism are on the rise. In Twilight of Democracy , prize-winning historian Anne Applebaum argues that we should not be surprised by this change: there is an inherent appeal to political systems with radically simple beliefs, especially when they benefit the loyal to the exclusion of everyone else. People are not just ideological, Applebaum contends in this captivating extended essay; they are also practical, pragmatic, and opportunist. The authoritarian and nationalist parties that have arisen within modern democracies offer new paths to wealth or power for their adherents. Describing politicians, journalists, intellectuals, and others who have abandoned democratic ideals in the UK, US, Spain, Poland, and Hungary, Applebaum reveals the patterns that link the new advocates of illiberalism and charts how they use conspiracy theory, political polarization, social media, and nostalgia to change their societies.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

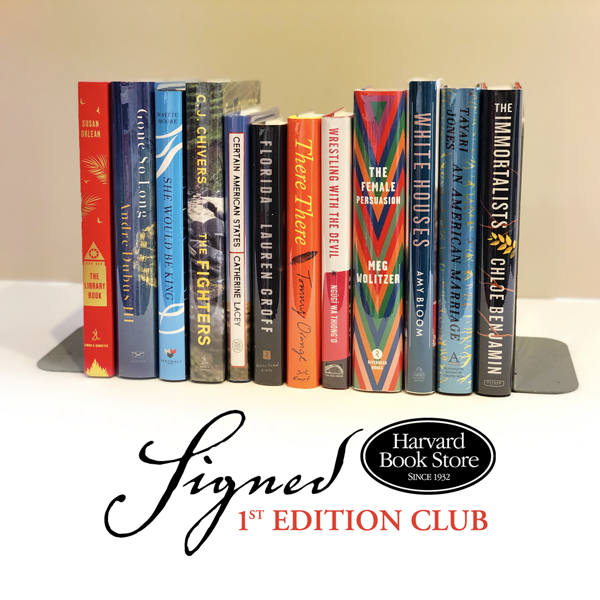

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

Twilight of Democracy

“How did our democracy go wrong? This extraordinary document . . . is Applebaum’s answer.” —Timothy Snyder, author of On Tyranny

A Pulitzer Prize–winning historian explains, with electrifying clarity, why elites in democracies around the world are turning toward nationalism and authoritarianism.

From the United States and Britain to continental Europe and beyond, liberal democracy is under siege, while authoritarianism is on the rise.

In Twilight of Democracy , Anne Applebaum, an award-winning historian of Soviet atrocities who was one of the first American journalists to raise an alarm about antidemocratic trends in the West, explains the lure of nationalism and autocracy. In this captivating essay, she contends that political systems with radically simple beliefs are inherently appealing, especially when they benefit the loyal to the exclusion of everyone else.

Despotic leaders do not rule alone; they rely on political allies, bureaucrats, and media figures to pave their way and support their rule. The authoritarian and nationalist parties that have arisen within modern democracies offer new paths to wealth or power for their adherents. Applebaum describes many of the new advocates of illiberalism in countries around the world, showing how they use conspiracy theory, political polarization, social media, and even nostalgia to change their societies.

Elegantly written and urgently argued, Twilight of Democracy is a brilliant dissection of a world-shaking shift and a stirring glimpse of the road back to democratic values.

- CIC National Capital Branch

Get the latest from Open Canada straight to your inbox!

Sign up for Dispatches, our FREE monthly newsletter

Book Review: Twilight of Democracy

Anne Applebaum. Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism. Signal/McClelland & Stewart, an imprint of Penguin Random House Canada, 2020.

By several measures, global democracy is in rude form. According to Freedom House, a think tank, 39 per cent of the world’s 7.7 billion people live under free political systems; 25 per cent more are partly free. Compare this snapshot with any other period in history, including that of the ‘greatest generation’ after 1945 or the years of détente in the 1970s (still less than a half century ago): most will count themselves fortunate to be alive today.

Yet if we dig a little deeper, the picture darkens. Across 34 countries surveyed by the Pew Research Center, 52 per cent of respondents were dissatisfied with democracy; only 44 per cent satisfied. Freedom House has recorded thirteen consecutive years of setbacks, ending in what it describes as today’s “leaderless struggle for democracy.” The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index for 2019 ranks only twenty-two states as full democracies — fifteen in Europe plus three in Latin America (Chile, Costa Rica and Uruguay), Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, New Zealand, Australia and Canada. Recent concerns over the electoral system, immigration and asylum policy, inequality and the role of money in criminal justice and politics have relegated the United States to the ranks of the “flawed democracies.” And without a single full democracy in continental Asia or Africa, where three quarters of the world’s population now lives, how far have we really come in the struggle to make democratic freedoms a global reality?

Anne Applebaum is as well placed to answer this question as anyone on the planet. A Pulitzer-prize-winning historian of the Soviet Gulag, chronicler of the USSR’s campaign to crush democracy in postwar central Europe and more recently of Stalin’s famine-genocide in Ukraine, she has had a ringside seat for the last quarter century in the political arenas of Poland, the United Kingdom and the United States, where she was born. The result is a richly textured, brilliantly composed essay on why in recent decades democracy has lost altitude, while dictators and xenophobes have been welcomed back into polite company from Budapest to Los Angeles.

Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism starts out in Poland and Hungary. Applebaum tells the story of brothers Jarosław and Janek Kurski, once activists in the same anti-Communist cause, who are today bitter foes, one a long-time editor of Poland’s leading liberal daily, the other an architect of state television’s decline into shabby alt-right chauvinism and conspiracy-mongering. Boris Johnson is tracked from his days predicting Brexit “won’t happen” around a dinner table to presiding unsteadily over it. Two chapters follow on populism in Spain and the rise of Trump’s awkward squad of grifters and reprobates.

Applebaum interweaves didactic anecdote with intellectual history, book-ending her argument with portraits of two dinner parties — one in 1999, when the guests basked in the afterglow of Europe reunited; another in 2019, with liberal democracy’s ranks thinned and under siege. Her conclusion is that we should all choose our friends carefully since, as the anti-Dreyfusards showed in 1894, today’s moderates quickly become tomorrow’s extremists.

Applebaum’s core message is that responsibility for keeping democracy vibrant rests with each one of us. When we’re complacent, or asleep at the wheel, bad things happen. She wants democratic vigilance to be a shared habit. Her book is a good-natured but serious warning about the new ‘banality of evil’ in our midst. She writes with a gift of expression that should take her appeal well beyond Timothy Snyder’s drier On Tyranny or Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s more academic How Democracies Die . For Applebaum, both freedom and tyranny are still possible outcomes. Our challenge is to chart the right path, as these seven sentences illustrate:

We may be doomed, like glittering, multiethnic Habsburg Vienna or creative, decadent Weimar Berlin, to be swept away into irrelevance. It is possible that we are already living through the twilight of democracy; that our society may already be heading for anarchy or tyranny, as the ancient philosophers and America’s founders once feared … . To some, the precariousness of the current moment seems frightening, and yet this uncertainty has always been there. … The checks and balances of Western constitutional democracies never guaranteed stability. Liberal democracies always demanded things from citizens: participation, argument, effort, struggle. They always required some tolerance for cacophony and chaos, as well as some willingness to push back at the people who create cacophony and chaos.

It is hard for most people to accept that nations change; that political change is constant and inevitable; that the global economy creates winners and losers; that complex problems need sophisticated solutions and careful deliberation. Democracy is not about instant gratification. It’s about sifting and balancing. In other words, the features that make democracy successful also make it dull, even alienating. But why is it in such acute crisis today?

“Democracy is not about instant gratification. It’s about sifting and balancing. In other words, the features that make democracy successful also make it dull, even alienating. But why is it in such acute crisis today?”

Applebaum’s chosen essay genre precludes a more thorough analysis of these deeper maladies. In short, this current crisis of established democracies is quite new. From Karl Popper’s full-throated celebration of liberal democracy in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) through to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), the big democracies stayed on a fairly even keel, even as Stalin rolled over Cold War central Europe and propped up Communist China. Vietnam caused ripples, as did economic chaos in the 1970s, briefly boosting the appeal of Moscow-backed autocrats. But by the 1980s and 1990s, dictators were in retreat as Soviet prestige evaporated in Afghanistan, the Warsaw Pact fell apart and the USSR dissolved.

So why have democracies hit new turbulence today? The answer, I believe, is fourfold.

First, in three quick steps — recognition under Nixon, appeasement under George H. W. Bush and promotion to the WTO under Bill Clinton and George W. Bush — the People’s Republic of China vaulted in a few decades from Cultural Revolution under Mao to world’s largest producer of merchandise goods under presidents Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping. For the first time, a one-party dictatorship with global surveillance and reserve currency ambitions enjoys trade surpluses with every major world economy. Ruthless exploitation of this economic leverage means US and other firms are unwilling to disengage, just as Beijing’s disregard for human rights and sponsorship of autocrats become more visible and more damaging than ever.

Second, Europe’s failure to hold out the prospect of EU accession to Ukraine, the three countries of the Caucasus, Turkey and North Africa fuelled a political backlash. Within the EU, the benefits of a wider, deeper union plateaued with the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, ushering in a new era of inwardness. Financial and refugee crises have further polarized European politics.

Third, as the United States and Britain sent manufacturing jobs offshore to China and elsewhere, they counted on their global leadership in technology, financial and other services to continue. The triple blows of 9/11, defeat in Iraq and the subprime meltdown forced the Anglosphere to rely even more heavily on Silicon Valley’s successes and London’s status as banker to Europe, China, Russia and the Gulf. They ignored the malign potential of social media platforms and dictator-fuelled corruption. The result has been Brexit, the greatest act of self-harm in modern British history, and the most disastrous American presidency in nearly two centuries.

Fourth, through all this Putin has preyed on America’s distraction to extend his shelf life. By 2010, he had tested soft and hard power in Georgia, Hungary and Poland; after 2011, he unleashed both in Syria, Ukraine and Libya. After 2014, he mounted the most aggressive “active measures” operations in Kremlin history to make Brexit happen and put Donald Trump in the White House. Facebook, Google and Twitter still give Putin’s information warfare order of battle instant access to nearly every household in the US, UK and other democracies.

In other words, by appeasing China, mothballing incentives for improved governance and giving Russia a direct channel into British and American psyches and politics, leading democracies have been authors of their own setbacks. Will twilight become darkness? My guess is no, though Applebaum has written this book because she thinks the jury is still out. One thing is certain. Without much more serious strategy to curb or counter the forces that precipitated this crisis — Chinese illiberalism, EU inertness, Anglo-American self-harm and Russian information warfare — the prospect of a starless, moonless future for democracy will only grow.

Why don’t more people care? How does unspeakable Trump remain over 40 per cent in the polls, while British citizens are still blissfully unaware of the under-the-carpet role played by Putin’s people in orchestrating Brexit? Mark Twain is often credited with saying, “it’s easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled.” This quip is a play on Jonathan Swift’s truism: “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it.” Except that, aptly for this era of disinformation, Mark Twain wrote no such thing. He did say, in 1906, “The glory which is built upon a lie soon becomes a most unpleasant incumbrance. … How easy it is to make people believe a lie, and how hard it is to undo that work again!” For now, most democracies seem intent on remaining encumbered. Only new leadership (and fresh crises) will force a reckoning.

Before you click away, we’d like to ask you for a favour …

Journalism in Canada has suffered a devastating decline over the last two decades. Dozens of newspapers and outlets have shuttered. Remaining newsrooms are smaller. Nowhere is this erosion more acute than in the coverage of foreign policy and international news. It’s expensive, and Canadians, oceans away from most international upheavals, pay the outside world comparatively little attention.

At Open Canada, we believe this must change. If anything, the pandemic has taught us we can’t afford to ignore the changing world. What’s more, we believe, most Canadians don’t want to. Many of us, after all, come from somewhere else and have connections that reach around the world.

Our mission is to build a conversation that involves everyone — not just politicians, academics and policy makers. We need your help to do so. Your support helps us find stories and pay writers to tell them. It helps us grow that conversation. It helps us encourage more Canadians to play an active role in shaping our country’s place in the world.

Related Articles

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE TWILIGHT OF DEMOCRACY

by Patrick E. Kennon ‧ RELEASE DATE: Jan. 12, 1995

A former CIA analyst hunts unsuccessfully for the reason why, if democracy seems so triumphant in the wake of communism's collapse, democratic nations such as the US, Japan, Germany, and the UK are suffering from angst and domestic discord. As a longtime veteran of perhaps the world's greatest intelligence bureaucracy, Kennon naturally sees the expert, or bureaucrat, as the apex of the political-bureaucratic-business triad that has been indispensable to the nation-state. The expert serves as an honest broker between politicians, who are ever ready to be compromised or corrupted, and the private sector, which if left unchecked can sink into an almost Hobbesian war of all against all characterized by the shifting conflicts among businesses, tribes, castes, and religious sects. The modern world has become so complex, notes Kennon, that politicians have ceded the handling of major issues to specialists and nonelected officials with technical competence. In the US, Kennon points to the Federal Reserve's influence on monetary policy and the Supreme Court's adjudication of abortion rights. In contrast, he points to newly industrialized countries (NICs) such as Singapore, Taiwan, Peru, Indonesia, and Mexico, where dictators insulate economic policy-making from popular democratic pressures by turning it over to their bureaucrats. This insulation enables the NICs to make the transition from the instability of the Third World to membership among the developed countries. Kennon's theories, while often sound on the sources of political unrest, echo those thinkers who earlier hailed Mussolini for keeping Italy's trains running on time and the Soviet Union for achieving phenomenal industrial growth rates. He also ignores the fact that the authoritarian NICs, far from providing order, can unleash chaos through sheer megalomania (e.g., the Shah of Iran, to bolster his military forces, was instrumental in raising oil prices in the 1970s). Kennon implies that economic progress without democracy is sufficient for national success. But his is a technocratic vision of national well-being.

Pub Date: Jan. 12, 1995

ISBN: 0-385-47539-X

Page Count: 320

Publisher: Doubleday

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Nov. 1, 1994

GENERAL NONFICTION

Share your opinion of this book

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 28, 1996

This is not the Nutcracker sweet, as passed on by Tchaikovsky and Marius Petipa. No, this is the original Hoffmann tale of 1816, in which the froth of Christmas revelry occasionally parts to let the dark underside of childhood fantasies and fears peek through. The boundaries between dream and reality fade, just as Godfather Drosselmeier, the Nutcracker's creator, is seen as alternately sinister and jolly. And Italian artist Roberto Innocenti gives an errily realistic air to Marie's dreams, in richly detailed illustrations touched by a mysterious light. A beautiful version of this classic tale, which will captivate adults and children alike. (Nutcracker; $35.00; Oct. 28, 1996; 136 pp.; 0-15-100227-4)

Pub Date: Oct. 28, 1996

ISBN: 0-15-100227-4

Page Count: 136

Publisher: Harcourt

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 1996

More by E.T.A. Hoffmann

BOOK REVIEW

by E.T.A. Hoffmann ; adapted by Natalie Andrewson ; illustrated by Natalie Andrewson

by E.T.A. Hoffmann & illustrated by Julie Paschkis

TO THE ONE I LOVE THE BEST

Episodes from the life of lady mendl (elsie de wolfe).

by Ludwig Bemelmans ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 23, 1955

An extravaganza in Bemelmans' inimitable vein, but written almost dead pan, with sly, amusing, sometimes biting undertones, breaking through. For Bemelmans was "the man who came to cocktails". And his hostess was Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe), arbiter of American decorating taste over a generation. Lady Mendl was an incredible person,- self-made in proper American tradition on the one hand, for she had been haunted by the poverty of her childhood, and the years of struggle up from its ugliness,- until she became synonymous with the exotic, exquisite, worshipper at beauty's whrine. Bemelmans draws a portrait in extremes, through apt descriptions, through hilarious anecdote, through surprisingly sympathetic and understanding bits of appreciation. The scene shifts from Hollywood to the home she loved the best in Versailles. One meets in passing a vast roster of famous figures of the international and artistic set. And always one feels Bemelmans, slightly offstage, observing, recording, commenting, illustrated.

Pub Date: Feb. 23, 1955

ISBN: 0670717797

Page Count: -

Publisher: Viking

Review Posted Online: Oct. 25, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1955

More by Ludwig Bemelmans

developed by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans ; illustrated by Steven Salerno

by Ludwig Bemelmans

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Claremont Review of Books

- Book Reviews

- Digital Exclusive

Twilight of Democracy

A senior fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Francis Fukuyama has lately been speaking ill of democracy to readers unused to hearing it spoken ill of.

Books Reviewed

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

A review of Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy , by Francis Fukuyama

A senior fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Francis Fukuyama has lately been speaking ill of democracy to readers unused to hearing it spoken ill of. Fukuyama’s gift is a mix of radicalism and common sense. He has always been early to spot the logic behind big social and political transformations. Even before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, he wrote a widely cited essay, “The End of History?” that cast the difficulties of the Soviet empire as portending an international triumph of liberal democracy. Although others had described the West’s exit from industrial-age culture, it was Fukuyama who gave the first convincing description, in The Great Disruption (1999) and Our Posthuman Future (2002), of the information-age culture we were migrating into.

Fukuyama has been modest about his latest project, a two-volume survey of political regimes, which opened with The Origins of Political Order (reviewed by Stanley Kurtz in the Fall 2011 CRB ) and now concludes with Political Order and Political Decay. It began as a mere update of his mentor Samuel Huntington’s Political Order in Changing Societies (1968), but it has grown into something more ambitious and original. Fukuyama’s first volume opened with China’s mandarin bureaucracy rather than the democracy of ancient Athens, shifting the methods of political science away from specifically Western intellectual genealogies and towards anthropology. Nepotism and favor-swapping are man’s basic political motivations, as Fukuyama sees it. Disciplining those impulses leads to effective government, but “repatrimonialization”—the capture of government by private interests—threatens whenever vigilance is relaxed. Fukuyama’s new volume, which describes political order since the French Revolution, extends his thinking on repatrimonialization, from the undermining of meritocratic bureaucracy in Han China through the sale of offices under France’s Henri IV to the looting of foreign aid in post-colonial Zaire. Fukuyama is convinced that the United States is on a similar path of institutional decay.

He asks the reader to review the arguments against democracy commonly made in the 19th century, “since a number of them remain salient even if few people are willing to articulate them openly today.” That goes for Fukuyama himself. His argument runs through the borderlands separating political philosophy from political science. Political philosophy asks which government is best for man. Political science asks which government is best for government. It is sometimes difficult to tell which discipline Fukuyama is practicing. His criticisms of democracy can sound mumbled and esoteric.

Political decline, Fukuyama insists, is not the same thing as civilizational collapse. As a political philosopher, he is attached to democracy, acknowledging that “[t]he right to participate politically grants recognition to the moral personhood of the citizen.” But as a political scientist, he sees “an inherent tension between democracy and what we now call ‘good governance.’” Where a political philosopher might deplore bureaucracy insofar as it is “unaccountable,” Fukuyama the political scientist reveres it to the extent it is “autonomous.” He notes the consistently high standards of Germany’s officials since Otto von Bismarck’s chancellorship, regardless of whether the government they served was peaceful or belligerent. (Even the Nazis had a progressive side, passing in 1933 a Law for the Re-establishment of a Career Civil Service.) Fukuyama is not the first to remark that wars can spur government efficiency—even if front-line soldiers are the last to benefit from it. China’s “Warring States” period in the 5th century B.C. provided the impetus for its bureaucratic achievements. The munificent welfare states of postwar Europe rest, Fukuyama believes, on the continent’s “extraordinarily high level of violence” between the French Revolution and World War II.

Relative to the smooth-running systems of northwestern Europe, American bureaucracy has been a dud, riddled with corruption from the start and resistant to reform. Patronage—favors for individual cronies and supporters—has thrived. In the late 19th century, up to seven eighths of junior postmaster jobs changed hands with every new administration. Even today, the number of positions staffed on political rather than professional grounds (including most of our most important ambassadorships) vastly exceeds that in Europe. Under President Andrew Jackson, the U.S. pioneered modern clientelism, which Fukuyama distinguishes from patronage by its mass character and its tight link to vote-soliciting. Clientelism is an ambiguous phenomenon: it is bread and circuses, it is race politics, it is doing favors for special classes of people. Fukuyama notes, for instance, that since the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wound down, “half of all new entrants to the federal workforce have been veterans.” Clientelism is both more democratic and more systemically corrupting than the occasional nepotistic appointment.

Fukuyama has an explanation for why modern mass liberal democracy has developed on clientelistic lines in the U.S. and meritocratic ones in Europe. The United States was born as a democratic country. Its institutions grew out of horse-trading. In Europe, democracy, when it came, had to adapt itself to longstanding pre-democratic institutions, and to governing elites that insisted on established codes and habits. Where strong states precede democracy (as in Germany), bureaucracies are efficient and uncorrupt. Where democracy precedes strong states (as in the United States but also Greece and Italy), government can be viewed by the public as a piñata.

This is an elegant argument, but it relies on stereotypes and Fukuyama rides his evidence hard. Italy’s state and political culture are much stronger and more efficient than the national sprezzatura (nonchalance) would make them appear. Greece has indeed been corrupt throughout its modern history. As Fukuyama notes, in the 1870s it had seven times as many civil servants per capita as Britain. But the main source of its present-day corruption is the common European currency, the euro, membership in which gave Greece access to Germany’s credit line. This was a policy designed in Paris, Berlin, and Brussels, not in Athens. Fukuyama is right that Britain’s 19th-century Whigs had an easier time reforming the state than America’s 20th-century progressives, noting that “reform of the British public sector took place before expansion of the franchise.” But what was reformed before the great Reform bills was more Britain’s colonial administration than its metropolitan core.

Given America’s relative failure at building competent political institutions at home, it would be foolish to expect more success abroad. Fukuyama contrasts the painstaking Japanese development of Taiwan a century ago with the mess that the U.S. Congress, “eager to impose American models of government on a society they only dimly understood,” was then making of the Philippines. It is not surprising that Fukuyama was one of the most eloquent conservative critics of the U.S. invasion of Iraq from the very beginning. This led him into public arguments with several of his former Cold War allies. He won them handily.

P olitical Order and Political Decay is a bold argument disguised as a boring taxonomy of political forms. For much of the book, alas, the disguise is effective. Between Fukuyama’s opening discussion of post-Enlightenment governments and his concluding arguments about whether they are undergoing decadence and collapse is a 200-page section on “foreign institutions,” sketching the colonial and post-colonial fates of Nigeria, Tanganyika, Indonesia, and other places. Among American political scientists, Fukuyama is unusually free of political correctness. But there is something pro forma about his focus on these marginal political cultures. Though skeptical that the “legacy of colonialism” is an excuse for Third World ills, he winds up falling back on it nonetheless.

Fukuyama attributes Latin America’s difficulty in building solid institutions to a “‘birth defect’ of inequality” inherited from Spain. You would almost forget that Spain was sophisticated, energetic, and inventive enough to impose its language and culture on a quarter of the known world. In discussing Latin America, Fukuyama makes some characteristically bold arguments: the collapse of Central American and Andean Indian cultures on the eve of the Spaniards’ arrival, as well as the ease with which explorer Hernán Cortés enlisted local allies willing to make him master of Mexico, suggest that “neither [Indian] civilization was nearly as institutionalized as it appeared.” He also points to the rarity of inter-state warfare in Latin America as a cultural achievement, albeit one that may have rendered the region’s governments complacent and slack. In general, Spain’s culture is blamed for having eradicated “virtually any institutional trace of the dense pre-Columbian state structures that preceded them.”

Fukuyama also faults the colonizers of Africa, but for the opposite misdeed—an insufficient imposition of their own culture. “[S]overeignty was handed to the Nigerians on a platter by the British,” he writes. That would have been fine if there had been any British institutions left to build on, but there were not, and democracy was inadequate to the task of building them. Fukuyama notes that Nigerian corruption blossomed and Congolese mining output withered even though Africa overall was “more democratic than East Asia in the period between 1960 and 2000.”

What distinguishes once-colonized Vietnam and China and uncolonized Japan and Korea from these Third World basket cases is that the East Asian lands “all possess competent, high-capacity states,” in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, which “did not possess strong state-level institutions.” One suspects that this discussion of states is a euphemistic way of discussing societies. Either way, it is strength and competence, not any ethical or ideological orientation, that Fukuyama deems most important. He points out on many occasions, as he did in his first volume, that China—whether ancient, Maoist, or contemporary—has always lacked the “rule of law,” by which he means a law that is binding on rulers. Fukuyama leaves unclear where the strength of the state is supposed to come from, if not from law, but cultural failure and backward government are fatefully bound together: “While it may in some theoretical sense be possible for a country like Sierra Leone or Afghanistan to turn itself into an industrial powerhouse like South Korea through appropriate investment,” Fukuyama writes, “these countries’ lack of strong institutions forecloses this option for all practical purposes.”

By focusing in his first volume on ancient Chinese and Indian (and, later, Ottoman) institutions, Fukuyama provided a foil for the line of descent that led from ancient Greece and Rome to modern Europe and America, highlighting magnificently what is universal about our institutions and what contingent. This new volume’s forays into non-Western societies are less enlightening—partly because these societies are not altogether non-Western. The governing systems of most post-colonial states are knock-offs from the West, not alternatives to it. The chapters come in arbitrary order and are of exactly the wrong length—long enough to befuddle you with statistics, dates, and fun facts about dozens of different Third World regimes but not long enough to leave you feeling you’ve tapped into any profound insight about their governments. Too often in these sections, the author’s clear prose is at the service of vague subject matter. Abstractions beget abstractions, as in: “Part of the story of the Third Wave of democratizations in Europe and Latin America has to do with the reinterpretation of Catholic doctrine after Vatican II.” (Which part? “Has to do” how?) He writes sentences that manage to unsay themselves: “If anyone needs further convincing that geography, climate, and population influence but do not finally determine contemporary development outcomes, consider Argentina.”

And yet Fukuyama’s detour into the developing world allows him to make a commonsensical point that has been shrouded in taboos for a generation: politics is a matter of shared purpose. To this extent, while “diversity” can be a source of strength, it is more often a source of dissension and weakness. The tribal cast that U.S. clientelism has taken on in the age of affirmative action is a subject few academic political scientists will touch with a stick. This includes the generally bold Fukuyama, who will say only that “ethnicity serves as a credible indication that a particular political boss will deliver the goods to a targeted audience.” But Kenya, for instance, is far enough away to permit him to be much more specific: “Today, one of the main functions of ethnic identity is to act as a signaling device in the clientelistic division of state resources,” he writes. “[I]f you are a Kikuyu and can elect a Kikuyu president, you are much more likely to be favored with government jobs, public works projects, and the like.”

Fukuyama does not think ethnic homogeneity is a prerequisite for successful politics, although he notes that it “enhanced” the prospects for state-building in China, Japan, Vietnam, and Korea, and had something to do with the development of certain non-Asian countries such as Costa Rica and Argentina. What he does insist on is that strong states need a cultural and political consensus if they are not to descend into the graft and pilfering that characterize such tribalized societies as Nigeria and Kenya. His shining example is the project of nation-building that Sukarno undertook in mid-20th-century Indonesia, uniting a vast, ethnically diverse archipelago behind Bahasa Indonesia as a lingua franca and anti-Communism as a state ideology. He sees a similar pattern in the Tanzania of Julius Nyerere after the mid-1960s, united linguistically by Swahili and ideologically by Ujamaa socialism. Fukuyama is an optimist about what a unified country can do, but a realist about the sacrifice it requires. “Any idea of a nation inevitably implies the conversion or exclusion of individuals deemed to be outside its boundaries,” he writes, “and if they don’t want to do this peacefully, they have to be coerced.”

Four hundred pages into the book, Fukuyama returns to the Western tradition, to its evolution in the past generation, and to the question of whether democracy has a future in it. In his view the United States “suffers from the problem of political decay in a more acute form than other democratic political systems.” It has kept the peace in a stagnant economy only by dragooning women into the workplace and showering the working and middle classes with credit. (He uses milder language.)

His explanation of what went wrong is that of a late 20th-century conservative who, perhaps chastened by lost wars and financial crises, has begun the best kind of root-and-branch reexamination of his principles. He believes that public-sector unions have colluded with the Democratic Party to make government employment more rewarding for those who do it and less responsive to the public at large. In this sense, government is too big. But he also believes that cutting taxes on the rich in hopes of spurring economic growth has been a fool’s errand, and that the beneficiaries of deregulation, financial and otherwise, have grown to the point where they have escaped bureaucratic control altogether. In this sense, government is not big enough.

Washington, as Fukuyama sees it, is a patchwork of impotence and omnipotence—effective where it insists on its prerogatives, ineffective where it has been bought out. He sees the Federal Reserve, Centers for Disease Control, and National Security Agency as parts of the government that are streamlined and potent. By contrast, he cites the Dodd-Frank financial act of 2010 as a regulation designed to be ineffective, in collusion with those it purported to regulate. In our time, government is—as people used to say of the Germans—either at your feet or at your throat.

The unpredictable results of democratic oversight have led Americans to seek guidance in exactly the wrong place: the courts, which have both exceeded and misinterpreted their constitutional responsibilities. “The courts, instead of being constraints on government, have become alternative instruments for the expansion of government,” Fukuyama writes. He worries about the logic Americans think they see behind the anti-democratic idea, introduced with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that a crusading Supreme Court can be an instrument of governmental reform. “So familiar is this heroic narrative to Americans,” he writes, “that they are seldom aware of how peculiar their approach to social change is.” Readers who remember the Cold War are bound to agree: the almost daily insistence of courts that they are liberating people by removing discretion from them gives American society a Soviet cast.

“[T]he two components of liberal democracy—liberal rule of law and mass political participation—are separable political goals,” Fukuyama writes. In the end, whether you have a streamlined European bureaucracy of the sort he admires or a clientelistic U.S.-style welfare state depends on whether you think it more important that liberal democracies be liberal or democratic. Until late in the 20th century, the American priority was unambiguously democracy. Fukuyama notes how, during the Cold War, U.S. foreign policymakers “would support a corrupt and clientelistic conservative party [abroad] over a cleaner left-wing one.” The same priorities prevailed at home. That changed with the emergence, in the middle of the 20th century, of legal and regulatory elites.

Fukuyama’s sympathies lie more than they used to with those who back the liberal part of liberal democracy, not the democratic part. “Effective modern states,” he writes, “are built around technical expertise, competence, and autonomy.” But he has some sympathy for the Tea Party and those European anti-immigration parties that lay the stress on the democratic part of liberal democracy. “[I]n many ways they are correct,” he writes, at least in their claim to have been locked out of policy-making by a conniving elite. Populist demands for democratic control of bureaucracies can look like “repatrimonialization,” but they are just as often self-defense.

High-handed bureaucrats and rabble-rousing populists are not separable threats to a political order. They are in a dialectical relationship. In the old days, roughly speaking, the Right was thought to stand for liberty and the Left for leveling. In the mind of today’s public, perhaps the Right stands for populism and the Left for administration. Each side wrongly thinks it can do without the other. Francis Fukuyama’s view is subtler, truer, and more depressing: the failing democracy in which we live is the system that, over the years, our thriving democracy chose.

Next in the fall 2014 Issue

Down to the bare wood, bright lights, big city, too much hype chasing too little wisdom.

Advertisement

Supported by

Can a 50-Year-Old Idea Save Democracy?

The economist and philosopher Daniel Chandler thinks so. In “Free and Equal,” he makes a vigorous case for adopting the liberal political framework laid out by John Rawls in the 1970s.

- Share full article

By Jennifer Szalai

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

FREE AND EQUAL: A Manifesto for a Just Society, by Daniel Chandler

The American political theorist John Rawls may be known for abstractions like “the original position” and “the difference principle,” but any mention of his name puts me in mind of something decidedly more tangible: cake. Consider the potentially combustible situation of two children who have been given a cake to share between them. How do you ensure that the division of the cake is fair and will elicit the least complaint?

The key is to involve both children in the process and to enforce a separation of powers: Assuming they’re old enough to handle a knife, one child can cut the cake and the other can get first pick of the slice. The child tasked with cutting will therefore be extremely motivated to divide the cake as evenly as possible.

Rawls included a version of the cake-cutting scenario in “A Theory of Justice,” his landmark 1971 book that the economist and philosopher Daniel Chandler wants to resurrect for a new era. In “Free and Equal,” Chandler argues that Rawls’s approach, which combines a liberal respect for individual rights and differences with an egalitarian emphasis on fairness, could be “the basis for a progressive politics that is genuinely transformative.”

If this is an opportune moment for Chandler’s book, it’s also a difficult one. At a time when political rancor and mistrust reign supreme, Chandler seeks to present an inspiring case for liberalism that distinguishes it from tepid complacency on the one hand and neoliberal domination on the other. Yet in doing the hard work of spelling out what a Rawlsian program might look like in practice, Chandler ends up illustrating why liberalism has elicited such frustration from its many critics in the first place.

Rawls’s theory was premised on the thought experiment of the “original position,” in which individuals would design a just society from behind a “veil of ignorance.” People couldn’t know whether they would be born rich or poor, gay or straight, Black or white — and so, like the child cutting the cake who doesn’t get to choose the first slice, each would be motivated to realize a society that would be accepted as fair even by the most vulnerable. This is liberalism grounded in reciprocity rather than selfishness or altruism. According to Rawls’s “difference principle,” inequalities would be permitted only as long as they promoted the interests of the least advantaged.

Chandler is a lucid and elegant writer, and there’s an earnest sense of excitement propelling his argument — a belief that Rawls’s framework for thinking through political issues offers a humane way out of the most intractable disputes. People might not agree on much, Chandler says, but the “veil of ignorance” encourages us to find a mutually agreeable starting point. If we don’t know what community we are born into, we should want a “reasonable pluralism.” We should also want the state “to maintain the conditions that are the basis for our freedom and equality as citizens.”

As an example, Chandler raises the thorny issue of free speech. “Political, moral and religious” speech “is integral to developing our sense of what is fair and how to live,” he writes, which is why it deserves robust protection. But since some speech, such as advertising, plays “no meaningful role” in helping us figure out how to live a good life, such speech can be limited. The idea is to balance individual and group freedoms with the need for peaceful coexistence. The state should protect the rights of gay people not to be discriminated against — even though the state cannot force anyone or any group to approve of gay relationships. Chandler, who is gay, suggests that premising gay rights on getting everyone to agree on the question of morality is a waste of energy: “For some people this” — the belief that homosexuality is a sin — “is part of their faith and no reasoned argument will persuade them otherwise.”

Chandler deserves credit for refusing to relegate his book to the airy realm of wistful abstraction. The last two-thirds of “Free and Equal” are given over to specific policy proposals. Some of them sound familiar enough — restricting private money in politics; beefing up civic education — while others are more far-reaching and radical, including the establishment of worker cooperatives, in which “workers decide how things are done,” and the abolition of private schools.

As impressive as his prescriptions are, I found their endless parade to be enervating. Chandler’s unwavering reasonableness made me feel as if I were floating in saline; after he laid out his terms and edged out countervailing arguments, there were no points of friction, no sharp edges that could serve as a goad to thought. He persuasively refutes the conflation of liberal egalitarianism with technocracy, and helpfully points out that an emphasis on technocratic competence “leaves many voters cold.” But despite his valiant efforts, the book enacts both the promise and the limitations of the theory it seeks to promote. It didn’t leave me cold, but it did leave me restless.

And in a way, that’s part of Chandler’s point: A Rawlsian framework encourages people with a variety of deeply held commitments to live together in mutual tolerance, free to figure out questions of individual morality and the good life for themselves. For anyone who venerates consensus in politics, this sounds appealing; given the fissures of our current moment, it also comes across as wildly insufficient.

“Free and Equal” includes a detailed chapter on “Rawls and His Critics,” but mostly navigates around anything that might truly rattle the Rawlsian framework. Regarding Katrina Forrester’s “In the Shadow of Justice” (2019) , a searching and brilliant history of how his ideas presumed a postwar consensus that was already fracturing at the time that “A Theory of Justice” was published, Chandler has little to say. He mentions her work in his endnotes, only in the context of how long it took Rawls to write his book and how it was initially received.

This felt to me like liberal flexibility in action — a form of accommodation that absorbed Forrester’s book by assimilating it into Chandler’s preferred terms. Perhaps Forrester wouldn’t be surprised by this move; as she puts it, “The capaciousness of liberal philosophy squeezed out possibilities for radical critique.”

But no philosophy is capacious enough to squeeze out the endless possibilities thrown up by reality. Among the stellar blurbs on the jacket of Chandler’s book is one that is spectacularly ill timed: It is by Columbia University’s president, Nemat Shafik, who has, in the last few weeks, tried to placate Republican lawmakers by revealing (typically confidential) details of disciplinary procedures against professors and calling in the police to clear out pro-Palestinian campus protests .

Shafik didn’t write this book, and Chandler isn’t responsible for what she does. But her endorsement suggests why even “Free and Equal” — as conscientious a paean to liberalism as one could imagine — feels so unequal to the fury of this moment.

FREE AND EQUAL : A Manifesto for a Just Society | By Daniel Chandler | Knopf | 414 pp. | $32

Jennifer Szalai is the nonfiction book critic for The Times. More about Jennifer Szalai

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Politics & Social Sciences

Promotions apply when you purchase

These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Audiobook Price: $11.81 $11.81

Save: $0.18 $0.18 (-2%)

Buy for others

Buying and sending ebooks to others.

- Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism Kindle Edition

- Print length 208 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Anchor

- Publication date July 21, 2020

- File size 2048 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought

From the Publisher

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- ASIN : B07ZN49QQ8

- Publisher : Anchor (July 21, 2020)

- Publication date : July 21, 2020

- Language : English

- File size : 2048 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 208 pages

- Page numbers source ISBN : 0771005873

- #7 in Civics

- #7 in 21st Century World History

- #28 in Ideologies & Doctrines

About the author

Anne applebaum.

Anne Applebaum is a historian and journalist. She is a staff writer for the Atlantic as well as a Senior Fellow at the Agora Institute, Johns Hopkins University. She is the author of several history books, including GULAG: A HISTORY which won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction; IRON CURTAIN, on the Sovietization of Eastern Europe after the war, which won the 2013 Cundill Prize for Historical Literature; and RED FAMINE, on the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33, which provides the background to today's Russian-Ukrainian conflict. In 2020 she published the bestselling TWILIGHT OF DEMOCRACY, which analyzed the appeal of autocracy to Western intellectuals and politicians.

Her newest book, AUTOCRACY, INC, published in July 2024, examines the network of dictatorships - Russia, China, Iran, Norht Korea, Venezuela, Zimbabwe and others - who now work together to support one another, preserve their power and undermine the democratic world.

Anne has been writing about Eastern Europe and Russia since 1989, when she covered the collapse of communism in Poland for the Economist magazine. She has also covered US, UK and European politics for a wide range of American and British publications. She is a former Washington Post columnist and a former deputy editor of the Spectator magazine. She is married to Radoslaw Sikorski, a Polish politician and writer, and lives in Poland and the U.S.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

Report an issue

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Morning After the Revolution review: a bad faith attack on ‘woke’

Nellie Bowles seeks simply to stoke ‘communal outrage’, whether over protesters, the unhoused or trans people

W riting on Substack in 2021 , Nellie Bowles described some of the less attractive qualities that motivated her work as a reporter: “I love the warm embrace of the social media scrum. One easy path toward the top of the list … is communal outrage. Toss something (someone) into that maw, and it’s like fireworks. I have mastered that game. For a couple of years, that desire for attention … propelled me more than almost anything else. I began to see myself less as a mirror and more as a weapon.”

Bowles is married to Bari Weiss, a former editor on the opinion section of the New York Times whose furious resignation letter earned her encomiums from Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and Donald Trump Jr.

But Bowles wrote that her decision to convert to the faith of her Jewish wife had actually softened her approach to journalism: “I want to cultivate my empathy not my cruelty. I am trying to go back to being closer to the mirror than the knife.”

However, her new book, Morning After the Revolution: Dispatches from the Wrong Side of History, is dazzling proof she is completely incapable of changing her approach to her profession.

Bowles is a former tech reporter for outlets including the Guardian and the New York Times . For many reporters, the decision to write a book comes from wanting to dig deeper into a particular subject, or a desire for freedom from the restrictions of one’s former employer. For Bowles, longform turns out to be the chance to jettison the standards of accuracy of her previous employers in favor of the wildest possible generalizations.

Here are a few fine examples: “The best feminists of my generation were born with dicks.” This is the author’s jaunty description of trans women, who, she informs us, are “the best, boldest” and “fiercest feminists”, who unfortunately – according to her – have concluded “that to be a woman is, in general, disgusting”.

On the ninth page of Bowles’s introduction, meanwhile, readers realize how much we must have underestimated the universal impact of the movement to Defund the Police. Did you know, for example, that “if you want to be part of the movement for universal healthcare … you cannot report critically on #DefundThePolice”?

Bowles identifies a similar problem with marriage equality: “If you want to be part of a movement that supports gay marriage … then you can’t question whatever disinformation is spread that week.”

The wilder the idea, the more likely Bowles is to include it, almost always in a way that can never be checked. To prove the vile effect of wokeness on the entire news business, she informs us that colleagues “at major news organizations” have “told me roads and birds are racist. Voting is racist. Exercise is super-racist. Worrying about plastic in the water is transphobic.” And a “cohort” took it “as gospel when a nice white lady said that being on time and objectivity were white values, and this was a progressive belief”.

Writing about a tent city in Echo Park, Los Angeles , Bowles explains why nobody living there was interested in a free hotel room: “Residents could not do drugs in the rooms. And the rooms were, of course, indoors. People high on meth and fentanyl prefer being outdoors, with no rules, with their friends.”

Predictably, the book reaches a whole new level of viciousness when it reveals Bowles’ attitude toward trans people.

Intelligent people know three essential facts about the debate over whether children under 18 should have access to hormones or surgery to make their bodies conform to the gender in which they think they belong.

First, a large majority of trans people of all ages never take hormones or get surgery. Second, nearly all of those who do choose to use medicine to alter their bodies report a dramatic improvement in personal happiness. Third, a very small number of those who have undergone surgery or taken hormones to block puberty do change their minds and opt for de-transition.

after newsletter promotion

Naturally, Bowles mentions none of those facts. According to her narrative, “the transition from Black Lives Matter to Trans Lives Matter was seamless … I don’t think this was planned or orchestrated. The movement simply pivoted.”

No mention, of course, of polls conducted by Christian nationalists and their allies which determined that the best new fundraising tool would be an all-out attack on trans people, including the denial of their very existence, as well as the introduction of hundreds of bills in state legislatures across the country to make this tiny minority as miserable as possible.

Instead, Bowles wants us to believe the debate is dominated by websites you might not have heard of, like Fatherly, which asserts: “All kids, regardless of their gender identity, start to understand their own gender typically by the age of 18 to 24 months.” One parent who appeared on PBS in 2023 is equally important in Bowles’s book, because she said her child started to let her parents know “she was transgender really before she could even speak”.

Needless to say, Bowles is horrified that as America became more aware of the existence of trans people, the number of clinics available to treat them grew to 60 by 2023. Then she makes another remarkable claim: “If a parent resists” medical changes requested by a child, “they can and do lose custody of their child.”

Is that true? I have no idea. If Bowles had written that sentence in the Times or the Guardian, her editor would most certainly have requested some sort of proof. Fortunately for her – but unfortunately for us – her publisher , a new Penguin Random House imprint, Thesis, does not appear to impose any outdated fact-checking requirements. The only visible standard here is, if it’s shocking, we’ll print it.

Morning After the Revolution is published in the US by Thesis

- Politics books

- US politics

- LGBTQ+ rights

Most viewed

Kristi Noem’s dog killing is pure Southern gothic

A literary critic’s take on the South Dakota governor’s memoir, “No Going Back.”

Toward the end of Fred Gipson’s 1956 classic, “Old Yeller,” Travis says, “It was going to kill something inside me to do it, but I knew then that I had to shoot my big yeller dog.”

Reading that scene again yesterday, damn if I wasn’t struck by the same storm of tears that overtook me in seventh grade. It’s a devastating moment, full of anguish, permanently embedded in the memory of anyone who’s read the novel or seen the movie.

If this week is any guide, a dog-killing scene will be permanently embedded in our memories of Kristi Noem, too. On Tuesday, the South Dakota governor published a political memoir called “ No Going Back .” But days before it appeared, everyone on planet Earth already knew about the passage in which Noem describes shooting her 14-month-old wire-haired pointer named Cricket .

What you can’t get from the 24/7 worldwide freakout, though, is how strange Cricket’s summary execution feels in context. That grisly story pops up in a chapter called “Will the World Awaken?” — right after Noem describes how much Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni wanted to meet her and right before she lays out a series of clichés called “The Noem Doctrine” — e.g. “Fight to win.”

In the fight with Cricket, Noem won the battle but lost the war . Yesterday in the Wall Street Journal, Republican garden gnome Karl Rove called “No Going Back” an act of “stunning self-destruction.” As Donald Trump considers whom to pick for his vice president, “bragging about shooting her puppy in a gravel pit ended her hopes of being selected.”

As a literary critic, I must object. The description of Cricket’s Last Stand is the one time in this howlingly dull book that Noem demonstrates any sense of setting, character, plot and emotional honesty. Otherwise, it’s mostly a hodgepodge of worn chestnuts and conservative maxims, like a fistful of old coins and buttons found between the stained cushions in a MAGA lounge.

And far too many people have been obsessing about Noem’s fantastical tête-à-tête with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. Come on — who among us hasn’t mistakenly believed that we once faced down the leader of the Hermit Kingdom? As I told Joseph Stalin, “We all make mistakes.”

But the central moment in Noem’s memoir is that transcendent scene of South Dakota gothic.

Picture it: Harvest season, “the Super Bowl of farming.” But it’s hunting season at their lodge, too. “Balancing both at full throttle is enough to break a family,” Noem says. She does everything possible to make sure friends from Georgia bag some pheasants, but Cricket — “out of her mind with excitement” — ruins everything. “I was livid,” Noem writes.

Then, on the way home from that disaster, Cricket attacks some beloved, irreplaceable chickens at a neighbors’ house. The mother — holding a baby, no less! — runs toward the melee, sobbing: “My chickens! No, not my chickens!” Noem pays for the birds and hauls Cricket into her truck. “She whipped around to bite me,” she says. “I hated that dog.”

Once home, Noem leads Cricket to the gravel pit and dispatches her. Then she spots a smelly old billy goat that she wants to kill, too. The first shot goes awry. She has to run across the pasture for more bullets “to finish the job.”

Construction workers taking a coffee break at her house witness all this carnage. “When they saw me heading their way,” Noem writes, “they put their cups down, got up and went back to work — in a real hurry.”

Gripping, right? Disturbing, even. Forget Travis and his beloved yellow cur. For a few glorious pages, Noem feels like a Flannery O’Connor character with tax cuts. Honestly, as someone who had to endure all 260 pages of “No Going Back,” I wish Noem had shot more dogs — or me.

Ron Charles reviews books and writes the Book Club newsletter for The Washington Post. He is the book critic for “ CBS Sunday Morning .”

No Going Back

The Truth on What’s Wrong With Politics and How We Move America Forward

By Kristi Noem

Center Street. 272 pp. $30

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

A WWII story by The Twilight Zone’s Rod Serling is published for the first time