MINI REVIEW article

Expanded yet restricted: a mini review of the soft skills literature.

- 1 Department of Education, Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 2 Department of Psychology, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Athens, Greece

There has been a progressively heightened preoccupation with soft skills among education stakeholders such as policymakers, educational psychologists, and researchers. Soft skill curricula have been considered these days and developed not only for graduates and as on-the-job training programs but also for students across all levels of education. However, different people mean different things when referring to soft skills. This review presents evidence to suggest that the use of the term “soft skills” has expanded to encompass a variety of qualities, traits, values, and attributes, as well as rather distinct constructs such as emotional labor and lookism. It is argued here that these infinite categories of things can be skills because soft skills research is primarily focused on what are the needs and requirements in the world of work. This approach is problematic because it assigns characteristics to soft skills, which in turn affect the design of the soft skills curricula. For example, soft skills are often construed as decontextualized behaviors, which can be acquired and transferred unproblematically. The paper proposes that an in-depth and embedded approach to studying soft skills should be pursued to reach a consensus on what they are and how to develop them because otherwise they will always be expanded before restricted (as they have become ambiguous) in their meaning and definition.

Introduction

Suppose you are present in a communication encounter between two men, Joe and Martin. Joe looks upset and literally screams while recounting an incident that has happened to him:

“Can you believe this?,” , Joe starts, “CAN YOU BELIEVE HIM? THE NERVE (.) he actually ended up ordering me “shut up, already, and do as I say!” (sounds infuriated) Joe is breathing heavily.

Martin nods thoughtfully.

(0.7) “As if he was in charge of me (.) as if he owned me … Where does he come off telling me what to do? Who does he think he is?” Joe continues.

Martin nods again, pushing his glasses up the bridge of his nose.

(0.9) Joe seems lost in his thoughts.

“I still can’t believe that this happened to me (.) It still makes me furious … ”

Martin’s nodding continues.

< “Can you understand now why I acted the way I did?” Joe asks. “I was badly provoked = = What would you do if you were me?” >

Martin responds with a nod.

Throughout Joe’s outburst, Martin keeps nodding. Nodding, in this instance, is an expressed form of active listening ( Pasupathi et al., 1999 ; Browning and Waite, 2010 ). The behavior of listening as a unified whole, moreover, features most prevalently in the lists of communication skills encountered in the soft skills literature – educational, medical, management, policy, or other (see for example, Jain and Anjuman, 2013 ). However, is Martin’s behavior a communication skill as these lists inform us? Let us consider two alternative scenarios providing context for this exchange, which, hopefully, can help us decide.

In the first scenario, Martin is a clinical psychologist, and Joe is his client. Martin has been treating Joe for the past 2 years; he is, therefore, aware that Joe suffers from bipolar disorder and that, as part of this, he experiences, periodically, manic episodes, like the one he recounts in the aforementioned exchange taking place in a supermarket between him and a stranger. In this communication encounter, Martin’s nodding and listening are the expressive form of his active processing of the contents of this narrative. It can be argued that it realizes Martin’s relation to Joe (i.e., he is Joe’s therapist) and his intention to encourage him to let it out and that it is enacting Martin’s knowledge of Joe’s condition, the relevant symptoms, and the techniques to deal effectively with it. In line with this, it seems fair to suggest that Martin’s listening behavior is an effective communication strategy and that it can, therefore, be construed as a “communication skill.”

In the second scenario, Joe has just started working as an employee in his uncle’s business. He works along with other seven employees under a team leader (Jacob). The team reports to Martin, the line manager. Joe is difficult to work with and has been constantly reporting problems to Martin with either his team leader or other team members. In the above excerpt, he recounts a recent episode between him and his team leader, Jacob, when the former refuses to follow the agreed strategy during a negotiation meeting. The encounter between Joe and Martin is one of many within the past few weeks. In this instance, and contrary to what one might have expected from a line manager, Martin’s behavior toward Joe fails to articulate the sensible aim of reasoning with Joe and taking actions to ensure such fights come to an end. Martin’s behavior, therefore, seems to be guided by something different; a possible explanation could be that he fears his behavior might displease the boss, so he remains silent instead. If that is the case, could still the behavior of listening be construed as a “communication skill” within the context of this scenario?

These episodes aim to illustrate how meaningless it is to call listening – as a random sample of any of the behaviors commonly featured in the different soft skills lists – a communication skill, before having access to all contextual information that would allow making an informed judgment. However, as the review of the literature that follows highlights this is the norm conceptualization of soft skills: any behavior mobilized in a communication encounter can be taken out of context and find its place to a list of communication skills without any formal and scientific criterion for doing so. The review starts first with the norm approach in the conceptualization and use of the term “skill” – itself.

Sources and Search Strategy

The literature review for this mini-review article was undertaken at two separate points in time: in the first instance looking at the literature up to and including 2011 and later for years 2011–2020. During the first period (up to 2011), a review of the term soft skills formed part of the literature review undertaken as part of a doctorate thesis ( Touloumakos, 2011 ). During this period, (a) keyword searches using the term “soft skills” (but also “soft skills” AND “characteristics,” “soft skills” AND “nature,” “soft skills” AND “development”) were conducted through the scientific databases: Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus; (b) specific journals focusing on education, management, and the labor market were targeted and searched to meet the criteria of the doctoral research that looked at the difference between soft skills conceptualization in practice and in educational policy.

During this second period, the previous steps were reiterated to produce an up-to-date list of papers in which the term was used and defined. The author acknowledges that this article does not follow the methodology of a systematic review and that there is certainly scope for a thorough and systematic review on this topic in the future.

What Do We Mean by Skill?

The first known use of the term “skill” dates back in the 13th century (Merriam-Webster’s, 2019). Skill is considered as the “dexterity or coordination…in the execution of tasks” (typically of physical nature), as the “ability to use one’s knowledge effectively and readily in execution and performance,” and as “learned power of doing something competently.” The practical disposition of skill is acknowledged in these definitions. It is also highlighted in the work of Ryle (1949) and Polanyi (1962) , according to who skill is construed as what knowledge sets in action (know-how and know-that, respectively), and, therefore, the two (knowledge and skill) are seen as “reciprocally constitutive” ( Orlikowski, 2002 ). For the purposes of this paper, I adopt the view of skill as what knowledge sets in action (know-how).

The Expansion of Skills: The Emergence of the Soft Skills Category

Contributing factors in the expansion of the term skill.

Over the years, the term skill has expanded considerably, to the point that its meaning became vague. In recent discourse, especially, it has taken on a range of meanings, and as a result, it refers, frequently, to “what is not skill” ( Hart, 1978 ). Indicatively, the term often refers to attitudes, traits, volitions, and predispositions ( inter alia , Payne, 2004 ; Clarke and Winch, 2006 ) and is sometimes confused, and even interchangeably used, with terms such as expertise and competence ( Payne, 2000 ; Pring, 2004 ; Eraut and Hirsch, 2007 ). Its gradual expansion has meant (and is reflected in) the emergence of new skills categories and subcategories (indicatively: generic, soft, interpersonal, etc.). Key contributing factors toward such gradual expansion of the term skill are identified at three levels. The first is at the rhetorical level; the second is at the definitional level; and the third level is at the dispositional character of term itself within different scientific fields.

Focusing on the rhetorical level, in recent years, there has been a linguistic transition from terms such as “skilled work” and “skilled labor” to “skills.” Payne’s paper highlights this shift:

Whereas the Carr Report of 1958 (HMSO 1958: 10), for example, could still talk of “ skilled craftsmen ” [my emphasis] as being the “backbone of industry,” 40 years on, The Learning Age (Department for Education and Employment 1998: 65) was employing a much wider discourse of “basic skills,” “employability skills,” “technician skills,” “management skills,” and “key skills” ( Payne, 2000 , p. 353).

As is evident, the term “skill” (i.e., a noun) began to be used as an independent concept and replaced the use of the term as a characteristic referring to people and professions for example “skilled craftsmen,” “skilled labor,” and “skilled trades” (i.e., an adjective) in the policy rhetoric. The consistency of the use of “skill” in the literature reflects a tendency to turn the abstract notion of a “skilled craftsman” into something more concrete. In this transition, one can identify a reified conceptualization of skill, according to which “skill” is an entity – often a property of an individual (see Sfard, 1998 ; Clarke and Winch, 2006 ).

At the definitional level, the criteria of what counts as skill expanded considerably, which naturally meant the expansion of the term “skill” as well. Relevant here is the ongoing debate around which jobs should be placed on the high skills end of the spectrum (see Lloyd and Payne, 2008 ). In Marx’s work (1970), for example, distinguishing criteria for skilled job included the high wages and low levels of physical labor at the same time. More recent seminal theoretical work summarizes the criteria distinguishing “unskilled” and “skilled” jobs ( Lloyd and Payne, 2008 ). The thinking behind such distinction is quite different from that of Marx. The authors discuss as an example (p. 1–2) the emergence of categories such as “emotional labor” ( Hochschild, 1979 , 1983 ) as a form of skilled labor “ requiring a range of quite complex and sophisticated abilities (see Bolton, 2004 , 2005 ; Korczynski, 2005 ).” The additional criteria for “what count as skill” in this work suggest a progressively ambiguous use of skill, which destined to term “skill” itself to ambiguity.

Third was the versatility of the term rendering it useful within the context of a range of scientific disciplines. Research on skills is rampant in the international literature, for example in cognitive studies – since many decades now – ( Anderson et al., 1996 , 1997 ), in education ( Clarke and Winch, 2006 ; Eraut and Hirsch, 2007 ; Ritter et al., 2018 ), in policy-making ( Wolf, 2004 , 2011 ; Ewens, 2012 ; World Economic Forum [WEF], 2015 ; OECD, 2016 ; LINCS, 2020 ), in labor market studies ( Meager, 2009 ; Kok, 2014 ), in management ( Kantrowitz, 2005 ; Stevenson and Starkweather, 2010 ), or in medicine ( Maguire and Pitceathly, 2002 ; Kurtz et al., 2005 ), to name a few. This evidence corroborates the multi-currency of “skill”,” which operationalizes cognitive mechanisms , human capital (the worker) , and jobs and tasks , depending on the discipline. It is because of this that we tend to speak of people and work in terms bundles of “skills” ( Darrah, 1994 ). The problem is this seems hard to avoid considering that the “deeper one looks into any activity the more knowledge and skill one is likely to find” ( Lloyd and Payne, 2009 , p. 622 drawing from Attewell, 1990 ).

Taken together, this evidence suggests not only the “ conceptual equivocation ” ( Payne, 2000 ) of the term as it is, but also the potentially perpetual emergence of new skills categories, a “galaxy of “soft,” “generic,” “transferable,” “social,” and “interactional’ skills ” (p. 354).

Soft Skills, Categories of Soft Skills, and Links Between Them

Soft skills were among the skills categories resulting from such expansion. While the emergence and use of the category of “soft skills” signified an important division between those skills that were cognitive and technical in nature – now frequently referred to as hard/technical skills – and those that were not, a unified view of the term in the literature has not been achieved. The genesis and use of the term are traced as far back as 1972 in training documents of the US Army (see Caudron, 1999 ; Moss and Tilly, 2001 ). Since then, the term has been expanded itself to comprise categories (in the various lists of soft skills) that include (but not exhaust to):

(a) Qualities (some of which one can see in the emotional intelligence literature) including adaptability, flexibility, responsibility, courtesy, integrity, professionalism, and effectiveness, and values such as trustworthiness and work ethic (see indicatively Wats and Wats, 2009 ; Touloumakos, 2011 ; Robles, 2012 ; Ballesteros-Sánchez et al., 2017 );

(b) Volitions , predispositions , attitudes like good attitude , willingness to learn , learning to learn other skills , hardworking , working under pressure, or uncertainty (see indicatively Stasz, 2001 ; Stasz et al., 2007 ; Andrews and Higson, 2008 ; Cinque, 2017 );

(c) Problem solving , decision making, analytical thinking/thinking skills , creativity/innovation , manipulation of knowledge , critical judgment (see indicatively Cimatti, 2016 ; Succi, 2019 ; Succi and Canovi, 2019 ; Thompson, 2019 );

(d) Leadership skills and managing skills (see indicatively Crosbie, 2005 ; Lazarus, 2013 ; Ballesteros-Sánchez et al., 2017 ), as well as self -awareness , managing oneself/coping skills (see Cimatti, 2016 ; Cinque, 2017 ; Thompson, 2019 );

(e) Interpersonal savvy/skills , social skills , and team skills , effective, and productive interpersonal interactions (see indicatively Kantrowitz, 2005 ; Bancino and Zevalkink, 2007 ; Succi and Canovi, 2019 ; Thompson, 2019 );

(f) Communication skills (see indicatively Wats and Wats, 2009 ; Mitchell et al., 2010 ; Stevenson and Starkweather, 2010 ; Robles, 2012 ; Cinque, 2017 ) including elements of negotiation , conflict resolution , persuasion skills , and diversity (see, in addition, Bancino and Zevalkink, 2007 ; Majid et al., 2012 ; Cinque, 2017 ; Succi and Canovi, 2019 ) as well as articulation work – that is orchestrating simultaneous interactions with people, information, and technology (see Hampson and Junor, 2005 ; Hampson et al., 2009 ); but also going as far as.

(g) Emotional labor (originally from Hochschild, 1983 ), and even in some cases (in service jobs for example).

(h) Aesthetics , professional appearance , and “ lookism ” (see Nickson et al., 2005 ; Warhurst et al., 2009 ; Robles, 2012 ); finally,

(i) Other areas covered included cognitive ability or processes (see Cimatti, 2016 ; Ballesteros-Sánchez et al., 2017 ; Thompson, 2019 ), ability to plan and achieve goals (see Cimatti, 2016 ).

Next to the expansion of the categories comprising soft skills, the hierarchical relationships between the different categories of soft skills, as featured in the literature, added to its ambiguity. An example is the relationship between communication and interpersonal skills. In some places, the two terms are used as interchangeable; in some other cases, they are seen as two distinct categories forming alongside other categories of the construct of soft skills ( Halfhill and Nielsen, 2007 ; Anju, 2009 ; Selvalakshmi, 2012 ; Jain and Anjuman, 2013 ). Finally, elsewhere, a hierarchical relationship exists between the two, namely the former is seen a part (a subcategory) of the latter ( Rungapadiachy, 1999 ; Hayes, 2002 ; Harrigan et al., 2008 ). The simultaneous overlap, submerging, vicinity, and yet disparity of terms such as communication and interpersonal skills is just one of the many in the skills literature (cf. Kinnick and Parton, 2005 , for discussion about overlap between communication and leadership). It becomes evident, accordingly, that these terms, much like the term soft skills has often become so stretched that their limits have become, in turn, vague. Their expansion meant actually that they became polysemous and, because of that, hard to grasp in a unified and organized way and therefore restricted in meaning and use.

This mini- review unveiled two important aspects in relation to the research and the conceptualization of soft skills. The first is that the rampant categories and lists of soft skills seem to be either the outcome of empirical work focusing on breaking down work activities (paraphrasing Lloyd and Payne, 2009 ) in addressing skills requirements, or recycled lists drawing from this work. This is the approach typically encountered in papers focusing on training graduates, training programes within organizations, and employers skills demands (for example Schulz, 2008 ; Constable and Touloumakos, 2009 ; Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2010 ; Majid et al., 2012 ; Ballesteros-Sánchez et al., 2017 ; Succi and Canovi, 2019 ). This, however, can only be taken to be a veneer of an evidence-based approach to soft skills conceptualization, which is key for their understanding and development for two reasons:

(a) Because same categories mean different things and different categories mean same things to stakeholders (researchers, participants, policymakers), and

(b) Because the aim of researching skills requirements is very different to the aim of researching soft skills characteristics and their nature (soft skills conceptualization).

It is at the level of the conceptualization, characterization, and definition, therefore, that we need to pursue an evidence-based approach, so as to achieve a common language and avoid getting lost in translation in the use of the various soft skills terms.

The second aspect is that, in line with the way the literature features soft skills, they encompass such a wide and diverse range of categories (for example qualities, traits, values, predispositions, etc.) that makes it impossible to think about them as a coherent whole. Arguably, the warehousing approach of soft skills categories development, abstracts behaviors from the context of their enactment and call them skills. This approach, by definition, has ramifications for our understanding of soft skills characteristics, which in turn affects the thinking that underpins their development. For example, given that skills in line with this view are seen as actions toward tasks, it brings to the center the person who acts ( Matteson et al., 2016 ) and, by extension, construes them as personal properties of a generic nature that can be first acquired and transferred uncomplicatedly across contexts ( Touloumakos, 2011 ). Given that this (much like any other) conceptualization of soft skills affects the way we think about their development and their inclusion in education curricula, it is clear that a more inclusive, bottom—up and embedded view would provide a more pragmatic and meaningful alternative in their study.

Author Contributions

This work has been undertaken in its entirety by AT.

Part of the work presented here was undertaken as a Ph.D. research.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The Ph.D. was funded by the Economics and Social Research Council and the State Scholarship Foundation. The author would like to thank Dr. Alexia Barrable for her thoughtful comments and insights on this work.

Anderson, J., Reder, L. M., and Simon, H. A. (1996). Situated learning and education. Educ. Res. 25, 5–11. doi: 10.3102/0013189X025004005

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anderson, J. R., Reder, L. M., and Simon, H. A. (1997). Situative versus cognitive perspectives: form versus substance. Educ. Res. 26, 18–21. doi: 10.3102/0013189X026001018

Andrews, J., and Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employability, ‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’ business knowledge: a European study. High. Educ. Eur. 33, 411–422. doi: 10.1080/03797720802522627

Anju, A. (2009). A holistic approach to soft skills training. IUP J. Soft Skills 3, 7–11.

Google Scholar

Attewell, P. (1990). What is skill? Work Occup. 17, 422–448. doi: 10.1177/0730888490017004003

Ballesteros-Sánchez, L., Ortiz-Marcos, I., Rivero, R. R., and Ruiz, J. J. (2017). Project management training: an integrative approach for strengthening the soft skills of engineering students. Intern. J. Eng. Educ. 33, 1912–1926.

Bancino, R., and Zevalkink, C. (2007). Soft skills: the new curriculum for hard-core technical professionals. Techniq. Connect. Educ. Careers 82, 20–22.

Bolton, S. C. (2004). “Emotion management in the workplace,” in Management, Work and Organisations , eds G. Burrell, M. Marchington, and P. Thompson (Red Global press: Macmillan International Higher Education).

Bolton, S. C. (2005). ‘Making up’ managers: the case of NHS nurses. Work, Employment and Society 19, 5–23. doi: 10.1177/0950017005051278

Browning, S., and Waite, R. (2010). The gift of listening: just listening strategies. Nurs. Forum 45, 150–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00179.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Caudron, S. (1999). The hard case for soft skills. Workforce 789, 60–67.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Arteche, A., Bremner, A. J., Greven, C., and Furnham, A. (2010). Soft skills in higher education: importance and improvement ratings as a function of individual differences and academic performance. Educ. Psychol. 30, 221–241. doi: 10.1080/01443410903560278

Cimatti, B. (2016). Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. Intern. J. Q. Res. 10, 97–130.

Cinque, M. (2017). MOOCs and soft skills: a comparison of different courses on creativity. J. Learn. Knowl. Soc. 13, 83–96.

Clarke, L., and Winch, C. (2006). A European skills framework? —but what are skills? Anglo-Saxon versus German concepts. J. Educ. Work 19, 255–269. doi: 10.1080/13639080600776870

Constable, S., and Touloumakos, A. K. (2009). Satisfying Employer Demands for Skills. London: The Work Foundation.

Crosbie, R. (2005). Learning the soft skills of leadership. Industr. Commerc. Train. 37, 45–51. doi: 10.1108/00197850510576484

Darrah, C. (1994). Skill requirements at work: rhetoric vs. reality. Work Occup. 21, 64–84. doi: 10.1177/0730888494021001003

Eraut, M., and Hirsch, W. (2007). The Significance of Workplace Learning for Individuals, Groups and Organisations (Monograph). Oxford: Oxford and Cardiff Universities.

Ewens, D. (2012). The Wolf Report on Vocational Education. London: Greater London Authority.

Halfhill, T. R., and Nielsen, T. M. (2007). Quantifying the “softer side” of management education: an example using teamwork competencies. J. Manag. Educ. 31, 64–80. doi: 10.1177/1052562906287777

Hampson, I., and Junor, A. (2005). Invisible work, invisible skills: interactive customer service as articulation work. New Technol. Work Employ. 20, 166–181. doi: 10.1177/0022185608099664

Hampson, I., Junor, A., and Barnes, A. (2009). Articulation work skills and the recognition of call centre competences in Australia. J. Industr. Relat. 51, 45–58. doi: 10.1177/0022185608099664

Harrigan, J., Rosenthal, R., Scherer, K. R., and Scherer, K. (eds) (2008). New Handbook of Methods in Nonverbal Behavior Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hart, W. A. (1978). Against skills. Oxford Rev. Educ. 4, 205–216. doi: 10.1080/0305498780040208

Hayes, J. (2002). Interpersonal Skills at Work. London: Routledge.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. Am. J. Sociol. 85, 551–575. doi: 10.1086/227049

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Jain, S., and Anjuman, A. S. S. (2013). Facilitating the acquisition of soft skills through training. IUP J. Soft Skills 7:32.

Kantrowitz, T. M. (2005). Development and Construct Validation of a Measure of soft Skills Performance. Ph. D. thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA.

Kinnick, K. N., and Parton, S. R. (2005). Workplace communication: what the apprentice teaches about communication skills. Bus. Commun. Q. 68, 429–456. doi: 10.1177/1080569905282099

Kok, S. (2014). Matching worker skills to job tasks in the Netherlands: sorting into cities for better careers. IZA J. Eur. Lab. Stud. 3:2. doi: 10.1186/2193-9012-3-2

Korczynski, M. (2005). Skills in service work: an overview. Human Resource Management Journal 15, 3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2005.tb00143.x

Kurtz, S. M., Silverman, D. J., Draper, J., van Dalen, J., and Platt, F. W. (2005). Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub.

Lazarus, A. (2013). Soften up: the importance of soft skills for job success. Phys. Exec. 39:40.

LINCS (2020). There is Nothing Soft About Sot Skills . Available online at: https://community.lincs.ed.gov/discussion/theres-nothing-soft-about-soft-skills (accessed May 26, 2019)

Lloyd, C., and Payne, J. (2008). What is a Skilled Job? Exploring Worker Perceptions of Skill in Two UK Call Centers. Oxford: Universities of Oxford and Cardiff.

Lloyd, C., and Payne, J. (2009). Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’ interrogating new skill concepts in service work–the view from two UK call centres. Work Employ. Soc. 23, 617–634. doi: 10.1177/0950017009344863

Maguire, P., and Pitceathly, C. (2002). Key communication skills and how to acquire them. Br. Med. J. 325, 697–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7366.697

Majid, S., Liming, Z., Tong, S., and Raihana, S. (2012). Importance of soft skills for education and career success. Intern. J. Cross Discipl. Subj. Educ. 2, 1037–1042.

Marx, K. (1970). Capital Vol. 1 . London: Lawrence and Wisehart.

Matteson, M. L., Anderson, L., and Boyden, C. (2016). Soft skills: a phrase in search of meaning. Port. Librar. Acad. 16, 71–88. doi: 10.1353/pla.2016.0009

Meager, N. (2009). The role of training and skills development in active labour market policies. Intern. J. Train. Dev. 13, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2419.2008.00312.x

Mitchell, G. W., Skinner, L. B., and White, B. J. (2010). Essential soft skills for success in the twenty-first century workforce as perceived by business educators. Delta Pi Epsilon J. 52, 43–53.

Moss, P., and Tilly, C. (2001). Stories Employers Tell: Race, Skill and Hiring in America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Nickson, D., Warhurst, C., and Dutton, E. (2005). The importance of attitude and appearance in the service encounter in retail and hospitality. Manag. Serv. Q. 15, 195–208. doi: 10.1108/09604520510585370

OECD (2016). Employment and Skills Strategies in Saskatchewan and the Yukon, OCED Reviews of Local Job Creation. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2002). Knowing in practice: enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organ. Sci. 13, 249–273. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.3.249.2776

Pasupathi, M., Carstensen, L. L., and Levenson, R. W. (1999). Responsive listening in long-married couples: a psycholinguistic perspective. J. Nonverb. Behav. 23, 173–193. doi: 10.1023/A:1021439627043

Payne, J. (2000). The unbearable lightness of skill: the changing meaning of skill in UK policy discourses and some implications for education and training. J. Educ. Policy 15, 353–369. doi: 10.1080/02680930050030473

Payne, J. (2004). “The changing meaning of skill,” in SKOPE Issues Papers [Warwick University: ESRC Centre on Skills, Knowledge and Organisational Performance (SKOPE)].

Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy. London: Routledge.

Pring, R. (2004). The skill revolution. Oxford Rev. Educ. 30, 105–116. doi: 10.1080/0305498042000190078

Ritter, B. A., Small, E. E., Mortimer, J. W., and Doll, J. L. (2018). Designing management curriculum for workplace readiness: developing students’ soft skills. J. Manag. Educ. 42, 80–103. doi: 10.1177/1052562917703679

Robles, M. M. (2012). Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Bus. Commun. Q. 75, 453–465. doi: 10.1177/1080569912460400

Rungapadiachy, D. M. (1999). Interpersonal Communication and Psychology for Health Care Professionals. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Ryle, G. (1949). The Concept of Mind. London: Hutchinson.

Schulz, B. (2008). The importance of soft skills: education beyond academic knowledge. NAWA J. Lang. Commun. 2, 146–154.

Selvalakshmi, M. (2012). Probing: an effective tool of communication. IUP J. Soft Skills 6:55.

Sfard, A. (1998). On metaphors for learning and the danger of choosing just one. Educ. Res. 27, 4–13. doi: 10.3102/0013189X027002004

Skill (2019). In Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary , 11th Edn, Available online at: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/skill (accessed November 23, 2019).

Stasz, C. (2001). Assessing skills for work: two perspectives. Oxford Econ. Pap. 53, 385–405. doi: 10.1093/oep/53.3.385

Stasz, C., Eide, E., Martorell, F., Goldman, C. A., and Constant, L. (2007). Post-Secondary Education in Qatar: Employer Demand, Student Choice, and Options for Policy , Vol. 644. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Stevenson, D. H., and Starkweather, J. A. (2010). PM critical competency index: IT execs prefer soft skills. Intern. J. Project Manag. 28, 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2009.11.008

Succi, C. (2019). Are you ready to find a job? Ranking of a list of soft skills to enhance graduates’ employability. Intern. J. Hum. Resourc. Dev. Manag. 19, 281–297. doi: 10.1504/IJHRDM.2019.100638

Succi, C., and Canovi, M. (2019). Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Stud. High. Educ. doi: 10.1504/ijhrdm.2019.100638

Thompson, S. (2019). The power of pragmatism: how project managers benefit from coaching practice through developing soft skills and self-confidence. Intern. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 17, 4–15.

Touloumakos, A. K. (2011). Now You See it, Now You Don’t: The Gap Between the Characteristics of Soft Skills in Policy and in Practice. Ph. D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford.

Warhurst, C., van den Broek, D., Hall, R., and Nickson, D. (2009). Lookism: the new frontier of employment: discrimination? J. Industr. Relat. 51, 131–136. doi: 10.1177/0022185608096808

Wats, M., and Wats, R. K. (2009). Developing soft skills in students. Intern. J. Learn. 15, 1–10. doi: 10.4324/9780429276491-1

Wolf, A. (2004). Education and economic performance: simplistic theories and their policy consequences. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 20, 315–333. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grh005

Wolf, A. (2011). Review of Vocational Education . London: DfE. Available online at: http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/pdfs/2011-wolf-report-vocational.pdf (accessed August 24, 2020).

World Economic Forum [WEF] (2015). New Vision for Education: Unlocking the Potential of Technology. New York, NY: WEF.

Keywords : soft skills, skill, soft skills conceptualization, soft skills development, curriculum design

Citation: Touloumakos AK (2020) Expanded Yet Restricted: A Mini Review of the Soft Skills Literature. Front. Psychol. 11:2207. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02207

Received: 31 May 2020; Accepted: 06 August 2020; Published: 04 September 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Touloumakos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna K. Touloumakos, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Power of Soft Skills: Our Favorite Reads

The the skills we call “soft” are the ones we need the most.

If you’re new to the workforce, you’ve probably read articles about the importance of building “soft skills”—empathy, resilience, compassion, adaptability, and others. The advice isn’t wrong. Research shows soft skills are foundational to great leadership and set high performers apart from their peers. They’re also increasingly sought by employers .

- EN Evelyn Nam is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy School, Columbia Journalism School, and Harvard Divinity School. She has reported on business and Asian American affairs. Currently, she is an assistant editor at Harvard Business Publishing.

Partner Center

The future of soft skills development: a systematic review of the literature of the digital training practices for soft skills

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

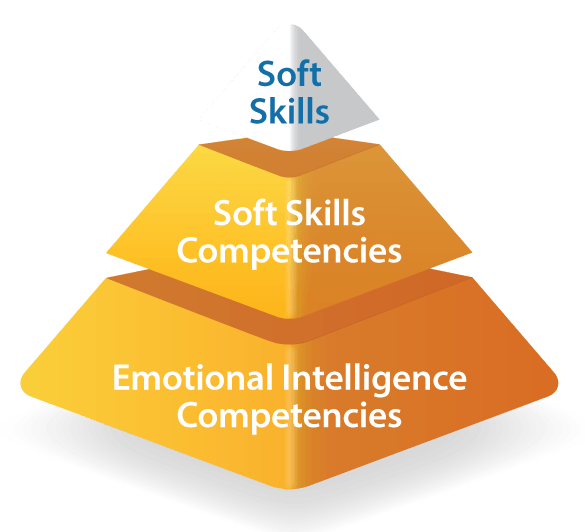

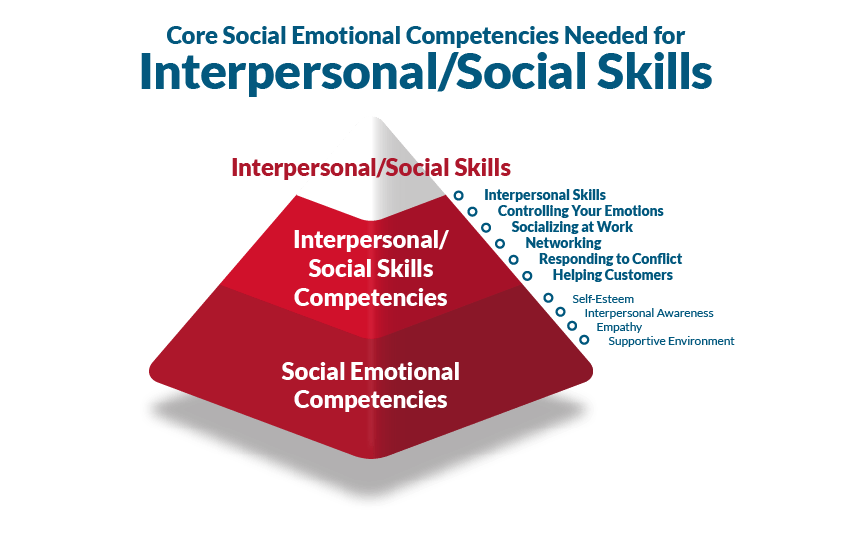

Soft skills are becoming increasingly important in the workplace. Due to their interpersonal nature and experiential face-to-face reality, they are often touted as nearly impossible to develop online; our study finds that an increasing body of literature is offering evidence and solutions to overcome impediments and promote digital technologies use in soft skills training. This review aims to perform a state of the art on the research on digital solutions for soft skills training using a systematic review of literature.

A systematic literature review following the PRISMA statement was conducted on the ISI Web of Science, where from 109 originally collected papers, 37 papers were held into consideration for the in-depth analysis.

This paper aims at bringing clarity for both research and practice to facilitate and promote more effective online training initiatives as well as innovative solutions for training in different areas.

In recent years, the global economy has been facing structural changes, rapidly evolving into the world of digital transformation. The unpredictability of the nature and pace of the changes will make it crucial that individuals in groups, organizations and societies alike develop skills for dealing with all kinds of situations, especially soft skills and in particular emotional and social competencies. In this work we look into the literature in a systematic way in order to understand the types of competences most addressed, most commonly used techniques and positive and negative results of the training...

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

The author declares that the submitted to Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society (Je-LKS) is original and that is has neither been published previously nor is currently being considered for publication elsewhere. The author agrees that SIe-L (Italian Society of e-Learning) has the right to publish the material sent for inclusion in the journal Je-LKS. The author agree that articles may be published in digital format (on the Internet or on any digital support and media) and in printed format, including future re-editions, in any language and in any license including proprietary licenses, creative commons license or open access license. SIe-L may also use parts of the work to advertise and promote the publication. The author declares s/he has all the necessary rights to authorize the editor and SIe-L to publish the work. The author assures that the publication of the work in no way infringes the rights of third parties, nor violates any penal norms and absolves SIe-L from all damages and costs which may result from publication.

The author declares further s/he has received written permission without limits of time, territory, or language from the rights holders for the free use of all images and parts of works still covered by copyright, without any cost or expenses to SIe-L.

For all the information please check the Ethical Code of Je-LKS, available at http://www.je-lks.org/index.php/ethical-code

- Ahmed, F., Capretz, L. F., Bouktif, S., & Campbell, P. (2012). Soft skills requirements in software development jobs: A cross-cultural empirical study. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 14(1), 58–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/13287261211221137

- Andrews, J., & Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employability, “soft skills” versus “hard” business knowledge: A european study. Higher Education in Europe, 33(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720802522627

- Asonitou, S. (2015). Employability Skills in Higher Education and the Case of Greece. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1202

- Baron, R. M. (2006). The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema, 18(1), 13–25. http://www.psicothema.com/psicothema.asp?id=3271

- Cimatti, B. (2016). Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for Quality Research, 10(1), 97–130. https://doi.org/10.18421/IJQR10.01-05

- Cinque, M. (2017). Moocs and soft skills: A comparison of different courses on creativity. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 13(3), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1386

- Clarke, S. J., Peel, D. J., Arnab, S., Morini, L., Keegan, H., & Wood, O. (2017). EscapED: A Framework for Creating Educational Escape Rooms and Interactive Games to For Higher/Further Education. International Journal of Serious Games, 4(3), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v4i3.180

- Cook, A., Smith, D. & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10):1435-43.

- Garcia, I., Pacheco, C., Méndez, F., & Calvo-Manzano, J. A. (2020). The effects of game-based learning in the acquisition of “soft skills” on undergraduate software engineering courses: A systematic literature review. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(5), 1327–1354. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22304

- Glazunova, O., Voloshina, T., & Korolchuk, V. (2020). Hybrid cloud-oriented learning environment for IT student project teamwork. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 77(3), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v77i3.3210

- Golowko, N. (2018). The need for digital and soft skills in the romanian business service industry. Management and Marketing, 13(1), 831–847. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2018-0008

- Holohan, A., & Holohan, A. (2019). Transformative Training in Soft Skills for Peacekeepers : Gaming for Peace Transformative Training in Soft Skills for Peacekeepers : Gaming for Peace. International Peacekeeping, 0(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2019.1623677

- Ibanez-Carrasco, F., Worthington, C., Rourke, S. & Hastings, C. (2020). Universities without Walls: A Blended Delivery Approach to Training the Next Generation of HIV Researchers in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research, 17, 4265.

- Jonassen, D. (2011). Supporting Problem Solving in PBL. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 5(2), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1256

- Laker, D., & Powell, J. (2011). The Differences Between Hard and Soft Skills and Their Relative Impact on Training Transfer. Human Resource Development Quartely, 22(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20063 111

- Lyons, P., & Bandura, R. P. (2020). Skills needs, integrative pedagogy and case-based instruction. Journal of Workplace Learning, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-12-2019-0140

- Mahajan, R., Gupta, P., & Singh, T. (2019). Massive Open Online Courses : Concept and Implications. Indian Pediatrics, 56, 489–495. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13312-019-1575-6

- Marques, J. (2013). Understanding the Strength of Gentleness: Soft-Skilled Leadership on the Rise. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1471-7

- Martins, H., Rouco, C., Piedade, L., & Borba, F. (2020). Soft Skills for Hard Times: Developing a Framework of Preparedness for Overcoming Crises Events in Higher Education Students.

- Merilainen, M., Rikka, A., Kultima, A., & Stenros, J. (2020). Game Jams for Learning and Teaching : International Journal Of Game-Based Learning, 10(2), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGBL.2020040104

- Miller, A. (2018). Innovative management strategies for building and sustaining a digital initiatives department with limited resources Digital Library Perspectives, 34(2), 117-136.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Reprint- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. 89(9), 873–880. https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/89/9/873/2737590

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, MayoWilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE.(2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal;372(160). doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

- Pisoni, G. (2019). Strategies for Pan-European Implementation of Blended Learning for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (I&E) Education. MDPI, 2–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020124

- Poce, A., Agrusti, F., & Rosaria Re, M. (2017). Mooc design and heritage education. Developing soft and work-based skills in higher education students. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 13(3), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1385

- Rasipuram, S., & Jayagopi, D. B. (2020). Automatic multimodal assessment of soft skills in social interactions : a review. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 13037–13060. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-08561-6

- Rhodes, A., Danaher, M. & Kranov, A (2018). Concurrent direct assessment of foundation skills for general education. On the Horizon, 26, 2, 79-90

- Roberts, J. (2019). Online learning as a form of distance education : Linking formation learning in theology to the theories of distance education. AOSIS, 75(1), 1–9. https://hts.org.za/index.php/hts/article/view/5345

- Rudenkol, L. G., Larionova, A. A., Zaitseva, N. A., Kostryukova, O. N., Bykasova, E. V, Garifullina, R. Z., & Safin, F. M. (2018). Conceptual Model Of Training Personnel For Small Business Services In The Digital Economy. Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods, 8(5), 283–296. http://mjltm.org/files/site1/user_files_a9608a/admin-A-10-1-114-60193c9.pdf

- Schech, S., Kelton, M., Carati, C., & Kingsmill, V. (2017). Simulating the global workplace for graduate employability. Higher Education Research and Development, 36(7), 1476–1489. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1325856

- Schneider, L. N., Meirovich, A., & Dolev, N. (2020). Soft Skills On-Line Development in Times of Crisis. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(1Sup2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/12.1sup2/255

- Stracke, C. M. (2017). The Quality of MOOCs : How to Improve the Design of Open Education and Online Courses for Learners ? 4th International Conference, Learning and Collaboration Technologies 2017, Part I, LNCS 10295, 285– 293. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58509-3

- Tseng, H., Yi, X., & Yeh, H. Te. (2019). Learning-related soft skills among online business students in higher education: Grade level and managerial role differences in self-regulation, motivation, and social skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 95(November 2018), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.035

- Vasileva, E. (2018). Developing the Creative Abilities and Competencies of Future Digital Professionals. Automatic Documentation and Mathematical Linguistics, 52(5), 248–256

- Virkus, S. (2019). The use of Open Badges in library and information science education in Estonia. Education for Information, 35(2), 155-172.

DB Error: Unknown column 'Array' in 'where clause'

Soft skills, do we know what we are talking about?

- Review Paper

- Published: 02 June 2021

- Volume 16 , pages 969–1000, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Sara Isabel Marin-Zapata ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6885-895X 1 ,

- Juan Pablo Román-Calderón ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4352-8513 1 ,

- Cristina Robledo-Ardila ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7205-2326 1 &

- Maria Alejandra Jaramillo-Serna ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3033-8494 1

5577 Accesses

20 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

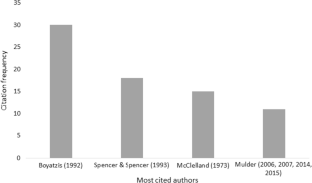

During the last decade, individual competencies and soft skills have reached a position of paramount importance among scholars in different fields. Yet, there seems to be a lack of consensus around the meaning of both concepts to the extent that they are sometimes used interchangeably. In response to this, we conducted a systematic review aimed at shedding light on the meaning of competencies and soft skills in business literature. The theoretical perspectives and methodological choices used by scholars were also accounted for as they are closely related to the definitions of these concepts. The systematic review presented in this paper addressed three specific research questions: (a) how are soft skills and competencies conceptualized in the reviewed literature?, (b) what are the main theories used in the study of soft skills and competencies?, and (c) methodologically, what are the main characteristics of those studies? The results indicate that there is still lack of consensus regarding the definitions of both terms. We also found that a large portion of the papers lacked a solid theoretical foundation, while the rest of the papers evidenced that business studies on competencies and soft skills suffer from theoretical dispersion. With regards to the methods used, we conclude that improvements must be made to help develop an understanding of competencies and soft skills. Consequently, a theoretical model explaining the relationships between these concepts was developed taking into account the sounder theoretical perspectives found in the literature review.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Soft Skills

Impact of Soft Skills Training on Knowledge and Work Performance of Employees in Service Organizations

Soft Skills: Demand and Challenges in the United States Workplace

Adner R, Helfat C (2003) Corporate effects and dynamic managerial capabilities. Strateg Manag J 24:1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.331

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad A, Kausar AR, Azhar SM (2015) HR professionals’ effectiveness and competencies: a perceptual study in the banking sector of pakistan. Int J Bus Soc 16:201–220

Google Scholar

Ahmed R, Anantatmula VS (2017) Empirical study of project managers leadership competence and project performance. EMJ Eng Manag J 29:189–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2017.1343005

Akhtar P, Khan Z, Frynas JG et al (2018) Essential micro-foundations for contemporary business operations: top management tangible competencies, relationship-based business networks and environmental sustainability. Br J Manag 29:43–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12233

Albandea I, Giret JF (2018) The effect of soft skills on French post-secondary graduates’ earnings. Int J Manpow 39:782–799. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2017-0014

Amedu S, Dulewicz V (2018) The relationship between CEO personal power, CEO competencies, and company performance. J Gen Manag 43:188–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306307018762699

Azasu S, Adewunm Y, Babatunde O (2018) South African stakeholder views of the competency requirements of facilities management graduates. Int J Strateg Prop Manag 22:471–478. https://doi.org/10.3846/ijspm.2018.6272

Baird SR (2014) An empirical investigation of successful, high performing turnaround professionals : application of the dynamic capabilities theory. Georgia State University

Balcar J (2016) Is it better to invest in hard or soft skills? Econ Labour Relat Rev 27:453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304616674613

Bamiatzi V, Jones S, Mitchelmore S, Nikolopoulos K (2015) The role of competencies in shaping the leadership style of female entrepreneurs: the case of North West of England, Yorkshire, and North Wales. J Small Bus Manag 53:627–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12173

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall Inc, Englewood Cliffs

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17:99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney J (1995) Looking inside for competitive advantage. Acad Manag Perspect 9:49–61

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182

Bartel-Radic A, Giannelloni JL (2017) A renewed perspective on the measurement of cross-cultural competence: an approach through personality traits and cross-cultural knowledge. Eur Manag J 35:632–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.02.003

Bartram D (2005) The Great Eight competencies: a criterion-centric approach to validation. J Appl Psychol 90:1185–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1185

Bass B, Riggio R (2006) Transformational leadership. Psychology Press, New York, NY

Book Google Scholar

Bautista-Mesa R, Molina Sánchez H, Ramírez Sobrino JN (2018) Audit workplace simulations as a methodology to increase undergraduates’ awareness of competences. Account Educ 27:234–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2018.1476895

Black J, Mendenhall M (1990) Cross-cultural training effectiveness: a review and a theoretical framework for future research. Acad Manag Rev 15:113–136. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1990.11591834

Bollmann G, Rouzinov S, Berchtold A, Rossier J (2019) Illustrating instrumental variable regressions using the career adaptability—job satisfaction relationship. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01481

Bonesso S, Gerli F, Pizzi C, Cortellazzo L (2018) Students’ entrepreneurial intentions: the role of prior learning experiences and emotional, social, and cognitive competencies. J Small Bus Manag 56:215–242

Borgatti SP, Cross R (2003) A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Manage Sci 49:432–445. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.4.432.14428

Boyatzis R (1982) The competent manager: a model for effective performance. Wiley, New York

Boyatzis R, Kolb D (1991) Assessing Individuality in learning: the learning skills profile. Educ Psychol 11:279–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341910110305

Boyatzis R, Kolb D (1995) From learning styles to learning skills: the executive skills profile. J Manag Psychol 10:3–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683949510085938

Calabor MS, Mora A, Moya S (2018) Adquisición de competencias a través de juegos serios en el área contable: un análisis empírico. Rev Contab 21:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsar.2016.11.001

Chaffer C, Webb J (2017) An evaluation of competency development in accounting trainees. Account Educ 26:431–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2017.1286602

Charoensap-Kelly P, Broussard L, Lindsly M, Troy M (2016) Evaluation of a soft skills training program. Bus Prof Commun Q 79:154–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490615602090

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Collet C, Damian H, du Karen P (2015) Employability skills: perspectives from a knowledge-intensive industry. Educ + Train 57:532–559. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2014-0076

Conchado A, Carot JM, Bas MC (2015) Competencies for knowledge management: development and validation of a scale. J Knowl Manag 19:836–855. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2014-0447

Costa SF, Caetano A, Santos SC (2016) Entrepreneurship as a career option: do temporary workers have the competencies, intention and willingness to become entrepreneurs? J Entrep 25:129–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971355716650363

Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull 52:281–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

De Carvalho MM, Rabechini Junior R (2015) Impact of risk management on project performance: the importance of soft skills. Int J Prod Res 53:321–340

Deaconu A, Osoian C, Zaharie M, Achim SA (2014) Competencies in higher education system: an empirical analysis of employers’ perceptions. Amfiteatru Econ 16:857–873

Delcourt C, Gremler DD, De Zanet F, van Riel ACR (2017) An analysis of the interaction effect between employee technical and emotional competencies in emotionally charged service encounters. J Serv Manag 28:85–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-12-2015-0407

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In: Buchanan DA, Bryman A (eds) The Sage handbook of organizational research methods. SAGE Publications, pp 671–689

Diin Fitri SE, Dahlan RM, Sukardi S (2018) From Penrose to Sirmon: the evolution of resource based theory. J Manag Leadersh 1:1–13

Dippenaar M, Schaap P (2017) The impact of coaching on the emotional and social intelligence competencies of leaders. South African J Econ Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v20i1.1460

Dunbar K, Laing G, Wynder M (2016) A content analysis of accounting job advertisements: skill requirements for graduates. e-J Bus Educ Scholarsh Teach 10:58–72

Edmondson AM, Mcmanus SE (2007) Fit in methodological management. Acad Manag Rev 32:1155–1179

European Union (2006) Key competences for life long learning, recommendation the European Parliament and the Council of 18th December 2006. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32006H0962 . Accessed 3 May 2021

Ferencikova S, Mühlbacher J, Nettekoven M et al (2017) Perceived differences of Austrian, Czech, and Slovakian managers regarding the need for change of future competencies: a self-affirmation perspective. J East Eur Manag Stud 22:144–168. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2017-2-144

Fernandes T, Morgado M, Rodrigues MA (2018) The role of employee emotional competence in service recovery encounters. J Serv Mark 32:835–849. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-07-2017-0237

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 68:103–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0142-x

Fleming E, Martin A, Hughes H, Zinn C (2009) Maximizing work-integrated learning experiences through identifying graduate competencies for employability: a case study of sport studies in higher education. Asia Pac J Coop Educ 20:189–201

Flöthmann C, Hoberg K, Gammelgaard B (2018a) Disentangling supply chain management competencies and their impact on performance: a knowledge-based view. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 48:630–655. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2017-0120

Flöthmann C, Hoberg K, Wieland A (2018b) Competency requirements of supply chain planners and analysts and personal preferences of hiring managers. Supply Chain Manag 23:480–499. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-03-2018-0101

Ghani EK, Rappa R, Gunardi A (2018) Employers’ perceived accounting graduates’ soft skills. Acad Account Financ Stud J 22(5):1–11

Gorenak M, Ferjan M (2015) The influence of organizational values on competencies of managers. E a M Ekon a Manag 18:67–83. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2015-1-006

Grant R (1996) Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: organizational capability as knowledge integration. Org Sci 7:375–387. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.4.375

Gruden N, Stare A (2018) The influence of behavioral competencies on project performance. Proj Manag J 49:98–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972818770841

Gruicic D, Benton S (2015) Development of managers’ emotional competencies: mind-body training implication. Eur J Train Dev 39:798–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-04-2015-0026

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1999) Análisis multivariante. Prentice Hall, Madrid

Harasim L (2017) Learning theory and online technologies. Taylor & Francis, Milton Park, pp 1–192. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203846933

Heesen R, Bright LK, Zucker A (2019) Vindicating methodological triangulation. Synthese 196:3067–3081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1294-7

Heinsman H, De Hoogh AHB, Koopman PL, Van Muijen JJ (2007) Competencies through the eyes of psychologists: a closer look at assessing competencies. Int J Sel Assess 15:412–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00400.x

Hendarman AF, Cantner U (2018) Soft skills, hard skills, and individual innovativeness. Eurasian Bus Rev 8:139–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-017-0076-6

Hennekam S (2016) Competencies of older workers and its influence on career success and job satisfaction. Empl Relations 38:130–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-05-2014-0054

Hitt M, Ireland R, Camp M, Sexton D (2001) Strategic entrepreneurship: entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation. Strateg Manag J 22:479–491. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.196

Hollenbeck G, McCall M, Silzer R (2006) Leadership competency models. Leadersh Q 17:398–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.04.003

Honig B, Davidsson P (2000) The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Acad Manag Proc 2000:B1–B6. https://doi.org/10.5465/APBPP.2000.5438611

Hurrell SA, Scholarios D, Thompson P (2013) More than a “humpty dumpty” term: strengthening the conceptualization of soft skills. Econ Ind Democr 34:161–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X12444934

Ibrahim R, Boerhannoeddin A, Bakare KK (2017) The effect of soft skills and training methodology on employee performance. Eur J Train Dev 41:388–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-08-2016-0066

Judge TA, Bono JE, Ilies R, Gerhardt MW (2002) Personality and leadership: a qualitative and quantitative review. J Appl Psychol 87:765–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765

Kaur D, Batra R (2018) Effectiveness of training and soft skills for enhancing the performance of banking employees. Prabandhan Indian J Manag 11:38–49

Kechagias K (2011) Teaching and assessing soft skills. Thessaloniki. 1st Second Chance School of Thessaloniki, Neapolis, Thessaloniki

Keevy M (2016) Using case studies to transfer soft skills (also known as pervasive skills) empirical evidence. Meditari Account Res 24:458–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-04-2015-0021

Khalili A (2016) Linking leaders’ emotional intelligence competencies and employees’ creative performance and innovative behaviour: evidence from different nations. Int J Innov Manag 20:1650069. https://doi.org/10.1142/s1363919616500699

Khan S (2018) Demystifying the impact of university graduate’s core competencies on work performance: a Saudi industrial perspective. Int J Eng Bus Manag. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979018810043

Khan K, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G (2003) Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med 96:118

Kisely S, Chang A, Crowe J et al (2014) Getting started in research: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Australas Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856214562077

Klein C, DeRouin RE, Salas E (2006) Uncovering workplace interpersonal skills: a review, framework, and research agenda. Int Rev Ind Organ Psychol 21:79–126

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 3rd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Knight B, Paterson F (2018) Behavioural competencies of sustainability leaders: an empirical investigation. J Org Chang Manag 31:557–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-02-2017-0035

Kogut B, Zander U (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Org Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.3.383

Kolb D (1984) Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. FT press, New Jersey

Kong H, Sun N, Yan Q (2016) New generation, psychological empowerment. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 28:2553–2569. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-05-2014-0222

Krawczyk-Sokolowska I, Pierscieniak A, Caputa W (2019) The innovation potential of the enterprise in the context of the economy and the business model. Rev Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00374-z

Laker DR, Powell JL (2011) The differences between hard and soft skills and their relative impact on training transfer. Hum Resour Dev Q 22:111–122

Lakshminarayanan S, Pai YP, Ramaprasad BS (2016) Competency need assessment: a gap analytic approach. Ind Commer Train 48:423–430. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-04-2016-0025

Lans T, Blok V, Gulikers J (2015) Show me your network and I’ll tell you who you are: social competence and social capital of early-stage entrepreneurs. Entrep Reg Dev 27:458–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1070537

Lans T, Verhees F, Verstegen J (2016) Social competence in small firms—fostering workplace learning and performance. Hum Resour Dev Q 27:321–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21254

Lara FJ, Salas-Vallina A (2017) Managerial competencies, innovation and engagement in SMEs: the mediating role of organisational learning. J Bus Res 79:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.002

Lawrance P, Lorsch J (1969) Organization and Environment. R.D. Irwin, Homewood

Lee YJ, Lee JH (2016) Knowledge workers’ ambidexterity: conceptual separation of competencies and behavioural dispositions. Asian J Technol Innov 24:22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/19761597.2016.1151365

Leoni R (2014) Graduate employability and the development of competencies. the incomplete reform of the “bologna process.” Int J Manpow 35:448–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2013-0097

Letonja M, Jeraj M, Marič M (2016) An empirical study of the relationship between entrepreneurial competences and innovativeness of successors in family SMEs. Organizacija 49:225–239. https://doi.org/10.1515/orga-2016-0020

Levant Y, Coulmont M, Sandu R (2016) Business simulation as an active learning activity for developing soft skills. Account Educ 25:368–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2016.1191272

Lewis RE, Heckman RJ (2006) Talent management: a critical review. Hum Resour Manag Rev 16:139–154

Liang Z, Howard PF, Leggat SG (2017) 360° management competency assessment: is our understanding adequate? Asia Pac J Hum Resour 55:213–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12108

Lipman V (2019) Management tip: soft skills can be hard to find. In: Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/victorlipman/2019/02/05/management-tip-soft-skills-can-be-hard-to-find/?sh=da8e3265f68e

Luna-Arocas R, Morley MJ (2015) Talent management, talent mindset competency and job performance: the mediating role of job satisfaction. Eur J Int Manag 9:28–51. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2015.066670

Maqboo R, Sudong Y, Manzoor N, Rashid Y (2017) The impact of emotional intelligence, project managers’ competencies, and transformational leadership on project success: an empirical perspective. Proj Manag J 48:58–75

Marabelli M, Newell S (2014) Knowing, power and materiality: a critical review and reconceptualization of absorptive capacity. Int J Manag Rev 16:479–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12031

Marsh HW, Morin AJS, Parker PD, Kaur G (2014) Exploratory structural equation modeling: an integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10:85–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700

Marzagão DSL, de Carvalho MM (2016) The influence of project leaders’ behavioral competencies on the performance of Six Sigma projects. Rev Bus Manag 18:609–632. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v18i62.2450

Matute J, Palau-Saumell R, Viglia G (2018) Beyond chemistry: the role of employee emotional competence in personalized services. J Serv Mark 32:346–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-05-2017-0161

Maydeu-Olivares A, Shi D, Fairchild AJ (2020) Estimating causal effects in linear regression models with observational data: the instrumental variables regression model. Psychol Methods 25:243–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000226

McClelland DC (1973) Testing for competence rather than for “intelligence.” Am Psychol 28:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034092

Mesly O (2015) Exploratory findings on the influence of physical distance on six competencies in an international project. Int J Proj Manag 33:1425–1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.06.001

Michael Clark J, Quast LN, Jang S et al (2016) GLOBE study culture clusters. Eur J Train Dev 40:534–553. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-03-2016-0016

Mikušová M, Čopíková A (2016) What business owners expect from a crisis manager? A competency model: survey results from Czech businesses. J Conting Cris Manag 24:162–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12111

Moss P, Tilly C (1996) ‘Soft’ skills and race: an investigation of black men’s employment problems. Work Occup 23:252–276

Mulder M (2006) EU-level competence development projects in agri-food-environment: the involvement of sectoral social partners. J Eur Ind Train. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590610651230

Mulder M (2007) Competencia: la esencia y la utilización del concepto en la formación profesional inicial y permanente. Rev Eur Form Prof 40:5–24

Mulder M (2014) Conceptions of professional competence. In: Billett S, Harteis C, Gruber H (eds) International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_5

Mulder M (2015) Professional competence in context – a conceptual study. In: AERA. Chicago, USA, pp 1–23

Ng HS, Kee DMH (2018) The core competence of successful owner-managed SMEs. Manag Decis 56:252–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-12-2016-0877

Ng HS, Kee DMH, Ramayah T (2016) The role of transformational leadership, entrepreneurial competence and technical competence on enterprise success of owner-managed SMEs. J Gen Manag 42:23–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630701604200103

Nijhuis S, Vrijhoef R, Kessels J (2018) Tackling project management competence research. Proj Manag J 49:62–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972818770591

Novak V, Žnidaršič A, Šprajc P (2015) Students’ perception of HR competencies. Organizacija 48:33–44. https://doi.org/10.1515/orga-2015-0003

OECD (2001) Definition and selection of competencies: theoretical and conceptual foundations (DeSeCo), Summary of the final report Key Competencies for a Successful Life and a Wellfunctioning Society. https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/41529556.pdf . Accessed 3 May 2021

OECD (2012) Better skills, better jobs, better lives a strategic approach to skills policies. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2017) OECD Skills Outlook 2017: skills and global value chains. OECD Publishing, Paris

Orr C, Sherony B, Steinhaus C (2011) Employer perceptions of student informational interviewing skills and behaviors. Am J Bus Educ 4:23–32. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v4i12.6615

Osagie ER, Wesselink R, Blok V, Mulder M (2019) Contextualizing individual competencies for managing the corporate social responsibility adaptation process: the apparent influence of the business case logic. Bus Soc 58:369–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316676270

Padilla-Meléndez A, Fernández-Gámez MA, Molina-Gómez J (2014) Feeling the risks: effects of the development of emotional competences with outdoor training on the entrepreneurial intent of university students. Int Entrep Manag J 10:861–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0310-y

Pang E, Wong M, Leung CH, Coombes J (2019) Competencies for fresh graduates’ success at work: perspectives of employers. Ind High Educ 33:55–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950422218792333

Penrose ET (1959) The theory of the growth of the firm. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Pérez-López MC, González-López MJ, Rodríguez-Ariza L (2016) Competencies for entrepreneurship as a career option in a challenging employment environment. Career Dev Int 21:214–229. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-07-2015-0102

Ploum L, Blok V, Lans T, Omta O (2018) Toward a validated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship. Organ Environ 31:113–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026617697039

Ployhart R, Moliterno T (2011) Emergence of the human capital resource: a multilevel model. Acad Manag Rev 36:127–150. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2011.55662569

Podmetina D, Soderquist KE, Petraite M, Teplov R (2018) Developing a competency model for open innovation. Manag Decis 56:1306–1335. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0445

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Poitras J, Hill K, Hamel V, Pelletier FB (2015) Managerial mediation competency: a mixed-method study. Negot J 31:105–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/nejo.12085

Poon J (2014) Do real estate courses sufficiently develop graduates’ employability skills? Perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Educ Train 56:562–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2013-0074

Pujol-Jover M, Riera-Prunera C, Abio G (2015) Competences acquisition of university students: do they match job market’s needs? Intang Cap 11:612–626. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.625

Quintana CDD, Ruiz JGM, Vila LE (2014) Competencies which shape leadership. Int J Manpow 35:514–535. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-05-2013-0107

Rainsbury E, Hodges D, Burchell N, Lay M (2002) Ranking workplace competencies: student and graduate perceptions. Asia-Pacific J Coop Educ 3:8–18

Rajaram R, Singh AM (2018) Competencies for the effective management of legislated business rehabilitations. S Afr J Econ Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1978

Ren S, Zhu Y (2017) Context, self-regulation and developmental foci: a mixed-method study analyzing self-development of leadership competencies in China. Pers Rev 46:1977–1996. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2015-0273

Robles MM (2012) Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Bus Commun Q 75:453–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569912460400

Salkind NJ (2010) Encyclopedia of research design. SAGE Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks

Schoonhoven C (1981) Problems with contingency theory: testing assumptions hidden within the language of contingency ‘theor. Adm Sci Q 26:349–377. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392512

Seidel A, Saurin TA, Marodin GA, Ribeiro JLD (2017) Lean leadership competencies: a multi-method study. Manag Decis 55:2163–2180. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-01-2017-0045

Semeijn J, Boone C, van der Velden R, van Witteloostuijn A (2005) Graduates’ personality characteristics and labor market entry an empirical study among dutch economics graduates. Econ Educ Rev 24:67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.03.006

Semeijn J, Van Der Heijden BIJM, Van Der Lee A (2014) Multisource ratings of managerial competencies and their predictive value for managerial and organizational effectiveness. Hum Resour Manag 53:773–794. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21592

Shah MN, Prakash A (2018) Developing generic competencies for infrastructure managers in India. Int J Manag Proj Bus 11:366–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-03-2017-0030

Shao J (2018) The moderating effect of program context on the relationship between program managers’ leadership competences and program success. Int J Proj Manag 36:108–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.05.004

Spector PE (2019) Do not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J Bus Psychol 34:125–137

Spencer LM, Spencer SM (1993) Competence at work: models for superior performance. Wiley, New York

Spowart J (2011) Hospitality students’ competencies: are they work ready? J Hum Resour Hosp Tour 10:169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2011.536940

Steele GA, Plenty D (2015) Supervisor-subordinate communication competence and job and communication satisfaction. Int J Bus Commun 52:294–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414525450

Stewart C, Wall A, Marciniec S (2016) Mixed signals: do college graduates have the soft skills that employers want? Compet Forum 14:276–281

Succi C (2019) Are you ready to find a job? Ranking of a list of soft skills to enhance graduates’ employability. Int J Hum Resour Dev Manag 19:281–297. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2019.100638

Suddaby R (2010) Challenges for institutional theory. J Manag Inq 19:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492609347564

Tam J, Sharma P, Kim N (2014) Examining the role of attribution and intercultural competence in intercultural service encounters. J Serv Mark 28:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2012-0266

Teece D, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 18:509–533. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2009.63.1.13

Teven J (2007) Teacher caring and classroom behavior: relationships with student affect and perceptions of teacher competence and trustworthiness. Commun Q 55:433–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370701658077

Tognazzo A, Gubitta P, Gerli F (2017a) Fostering performance through leaders’ behavioral competencies: an Italian multi-level mixed-method study. Int J Org Anal 25:295–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-07-2016-1044

Tognazzo A, Gubitta P, Gerli F (2017b) Fostering performance through leaders’ behavioral competencies. Int J Org Anal 25:295–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijoa-07-2016-1044

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14:207–222

Uhl-Bien M, Riggio RE, Lowe KB, Carsten MK (2014) Followership theory: a review and research agenda. Leadersh Q 25:83–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.007

Van Bakel M, Gerritsen M, Van Oudenhoven JP (2014) Impact of a local host on the intercultural competence of expatriates. Int J Hum Resour Manag 25:2050–2067. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.870292

Van Esch E, Wei LQ, Chiang FFT (2018) High-performance human resource practices and firm performance: the mediating role of employees’ competencies and the moderating role of climate for creativity. Int J Hum Resour Manag 29:1683–1708. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1206031

Vila LE, Pérez PJ, Coll-Serrano V (2014) Innovation at the workplace: do professional competencies matter? J Bus Res 67:752–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.039

Viviers HA, Fouché JP, Reitsma GM (2016) Developing soft skills (also known as pervasive skills) usefulness of an educational game. Meditari Account Res 24:368–389. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-07-2015-0045

Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in society: development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Wang Q, Waltman L (2016) Large-scale analysis of the accuracy of the journal classification systems of Web of Science and Scopus. J Informetr 10:347–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2016.02.003

Wang D, Feng T, Freeman S et al (2014) Unpacking the “skill-cross-cultural competence” mechanisms: empirical evidence from Chinese expatriate managers. Int Bus Rev 23:530–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.09.001

Wang L, Restubog S, Shao B et al (2018) Does anger expression help or harm leader effectiveness? The role of competence-based versus integrity-based violations and abusive supervision. Acad Manag J 61:1050–1072. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0460

Ward C, Bochner S, Furnham A (2001) The Psychology of Culture Shock. Routledge, London

Warner LH (2020) Developing interpersonal skills of evaluators: a service-learning approach. Am J Eval 41:432–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214019886064

Wats M, Wats RK (2009) Developing soft skills in students. Int J Learn 15:1–10

Weber MR, Finley DA, Crawford A, Rivera D (2009) An exploratory study identifying soft skill competencies in entry-level managers. Tour Hosp Res 9:353–361. https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2009.22