Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Bird Flu Is Bad for Poultry and Dairy Cows. It’s Not a Dire Threat for Most of Us — Yet.

Virtual reality: Treating pain and anxiety

What is a healthy nurse?

Broken trust

Diabetes innovations and access to care

Breaking barriers: Nursing education in a wheelchair

Nearly 100 measles cases reported in the first quarter, CDC says

Infections after surgery are more likely due to bacteria already on your skin than from microbes in the hospital − new research

Honoring our veterans

Supporting the multi-generational nursing workforce

Vital practitioners

From data to action

Many travel nurses opt for temporary assignments because of the autonomy and opportunities − not just the big boost in pay

Effective clinical learning for nursing students

Nurse safety in the era of open notes

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 3

- Data collection in qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- David Barrett 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1130-5603 Alison Twycross 2

- 1 Faculty of Health Sciences , University of Hull , Hull , UK

- 2 School of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr David Barrett, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, UK; D.I.Barrett{at}hull.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102939

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Qualitative research methods allow us to better understand the experiences of patients and carers; they allow us to explore how decisions are made and provide us with a detailed insight into how interventions may alter care. To develop such insights, qualitative research requires data which are holistic, rich and nuanced, allowing themes and findings to emerge through careful analysis. This article provides an overview of the core approaches to data collection in qualitative research, exploring their strengths, weaknesses and challenges.

Collecting data through interviews with participants is a characteristic of many qualitative studies. Interviews give the most direct and straightforward approach to gathering detailed and rich data regarding a particular phenomenon. The type of interview used to collect data can be tailored to the research question, the characteristics of participants and the preferred approach of the researcher. Interviews are most often carried out face-to-face, though the use of telephone interviews to overcome geographical barriers to participant recruitment is becoming more prevalent. 1

A common approach in qualitative research is the semistructured interview, where core elements of the phenomenon being studied are explicitly asked about by the interviewer. A well-designed semistructured interview should ensure data are captured in key areas while still allowing flexibility for participants to bring their own personality and perspective to the discussion. Finally, interviews can be much more rigidly structured to provide greater control for the researcher, essentially becoming questionnaires where responses are verbal rather than written.

Deciding where to place an interview design on this ‘structural spectrum’ will depend on the question to be answered and the skills of the researcher. A very structured approach is easy to administer and analyse but may not allow the participant to express themselves fully. At the other end of the spectrum, an open approach allows for freedom and flexibility, but requires the researcher to walk an investigative tightrope that maintains the focus of an interview without forcing participants into particular areas of discussion.

Example of an interview schedule 3

What do you think is the most effective way of assessing a child’s pain?

Have you come across any issues that make it difficult to assess a child’s pain?

What pain-relieving interventions do you find most useful and why?

When managing pain in children what is your overall aim?

Whose responsibility is pain management?

What involvement do you think parents should have in their child’s pain management?

What involvement do children have in their pain management?

Is there anything that currently stops you managing pain as well as you would like?

What would help you manage pain better?

Interviews present several challenges to researchers. Most interviews are recorded and will need transcribing before analysing. This can be extremely time-consuming, with 1 hour of interview requiring 5–6 hours to transcribe. 4 The analysis itself is also time-consuming, requiring transcriptions to be pored over word-for-word and line-by-line. Interviews also present the problem of bias the researcher needs to take care to avoid leading questions or providing non-verbal signals that might influence the responses of participants.

Focus groups

The focus group is a method of data collection in which a moderator/facilitator (usually a coresearcher) speaks with a group of 6–12 participants about issues related to the research question. As an approach, the focus group offers qualitative researchers an efficient method of gathering the views of many participants at one time. Also, the fact that many people are discussing the same issue together can result in an enhanced level of debate, with the moderator often able to step back and let the focus group enter into a free-flowing discussion. 5 This provides an opportunity to gather rich data from a specific population about a particular area of interest, such as barriers perceived by student nurses when trying to communicate with patients with cancer. 6

From a participant perspective, the focus group may provide a more relaxing environment than a one-to-one interview; they will not need to be involved with every part of the discussion and may feel more comfortable expressing views when they are shared by others in the group. Focus groups also allow participants to ‘bounce’ ideas off each other which sometimes results in different perspectives emerging from the discussion. However, focus groups are not without their difficulties. As with interviews, focus groups provide a vast amount of data to be transcribed and analysed, with discussions often lasting 1–2 hours. Moderators also need to be highly skilled to ensure that the discussion can flow while remaining focused and that all participants are encouraged to speak, while ensuring that no individuals dominate the discussion. 7

Observation

Participant and non-participant observation are powerful tools for collecting qualitative data, as they give nurse researchers an opportunity to capture a wide array of information—such as verbal and non-verbal communication, actions (eg, techniques of providing care) and environmental factors—within a care setting. Another advantage of observation is that the researcher gains a first-hand picture of what actually happens in clinical practice. 8 If the researcher is adopting a qualitative approach to observation they will normally record field notes . Field notes can take many forms, such as a chronological log of what is happening in the setting, a description of what has been observed, a record of conversations with participants or an expanded account of impressions from the fieldwork. 9 10

As with other qualitative data collection techniques, observation provides an enormous amount of data to be captured and analysed—one approach to helping with collection and analysis is to digitally record observations to allow for repeated viewing. 11 Observation also provides the researcher with some unique methodological and ethical challenges. Methodologically, the act of being observed may change the behaviour of the participant (often referred to as the ‘Hawthorne effect’), impacting on the value of findings. However, most researchers report a process of habitation taking place where, after a relatively short period of time, those being observed revert to their normal behaviour. Ethically, the researcher will need to consider when and how they should intervene if they view poor practice that could put patients at risk.

The three core approaches to data collection in qualitative research—interviews, focus groups and observation—provide researchers with rich and deep insights. All methods require skill on the part of the researcher, and all produce a large amount of raw data. However, with careful and systematic analysis 12 the data yielded with these methods will allow researchers to develop a detailed understanding of patient experiences and the work of nurses.

- Twycross AM ,

- Williams AM ,

- Huang MC , et al

- Onwuegbuzie AJ ,

- Dickinson WB ,

- Leech NL , et al

- Twycross A ,

- Emerson RM ,

- Meriläinen M ,

- Ala-Kokko T

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

728k Accesses

293 Citations

85 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

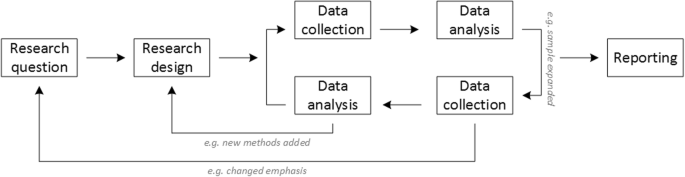

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

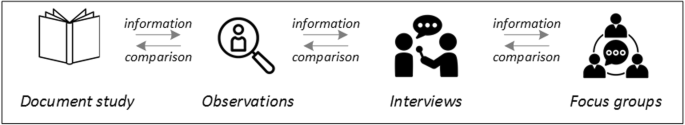

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

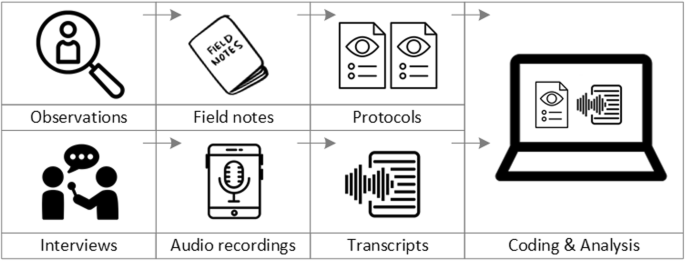

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

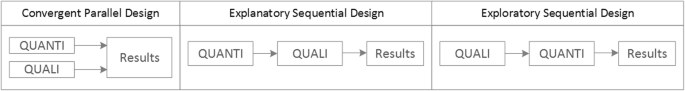

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of physical health screening for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a qualitative study

- Långstedt Camilla 1 ,

- Bressington Daniel 2 , 3 &

- Välimäki Maritta 1 , 4

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 321 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

58 Accesses

Metrics details

Despite worldwide concern about the poor physical health of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD), physical health screening rates are low. This study reports nurses’ and patients’ experiences of physical health screening among people with SSD using the Finnish Health Improvement Profile (HIP-F) and their ideas for implementation improvements.

A qualitative exploratory study design with five group interviews with nurses ( n = 15) and individual interviews with patients with SSD ( n = 8) who had experience using the HIP-F in psychiatric outpatient clinics. Inductive content analysis was conducted.

Two main categories were identified. First, the characteristics of the HIP-F were divided into the subcategories of comprehensive nature, facilitating engagement, interpretation and rating of some items and duration of screening. Second, suggestions for the implementation of physical health screening consisted of two subcategories: improvements in screening and ideas for practice. Physical health screening was felt to increase the discussion and awareness of physical health and supported health promotion. The HIP-F was found to be a structured, comprehensive screening tool that included several items that were not otherwise assessed in clinical practice. The HIP-F was also considered to facilitate engagement by promoting collaboration in an interactive way. Despite this, most of the nurses found the HIP-F to be arduous and too time consuming, while patients found the HIP-F easy to use. Nurses found some items unclear and infeasible, while patients found all items feasible. Based on the nurses’ experiences, screening should be clear and easy to interpret, and condensation and revision of the HIP-F tool were suggested. The patients did not think that any improvements to the HIP-F were needed for implementation in clinical settings.

Conclusions

Patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders are willing to participate in physical health screening. Physical health screening should be clear, easy to use and relatively quick. With this detailed knowledge of perceptions of screening, further research is needed to understand what factors affect the fidelity of implementing physical health screening in clinical mental health practice and to gain an overall understanding on how to improve such implementation.

Peer Review reports

The physical health state of people diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) is a global problem [ 1 ]. Typically, poor physical health results from a range of issues, including the impact of psychiatric symptoms on health behavior, adverse effects of prescribed medication, difficulties observing physical health concerns, lifestyle, diagnostic overshadowing, and patient unwillingness to report health problems [ 2 , 3 ]. These factors may lead to obesity, metabolic syndrome, coronary vascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, or cancer [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. High rates of infectious diseases such as hepatitis and HIV [ 7 ] and COVID-19 [ 8 ] have also been reported in patients with SSD. As an outcome of physical health issues, physical comorbidity is associated with psychiatric readmission [ 9 ] and high treatment costs. In Finland, the total healthcare costs caused by schizophrenia are approximately 700–900 million euros per year, mostly as a result of inpatient treatment costs [ 10 ]. Due to poor physical health, the life expectancy of persons with schizophrenia is approximately 20 years less than that of the general population [ 11 , 12 ]. Therefore, it is crucial that physical health screening is conducted regularly for patients with SSD. Improving regular screening helps to support earlier detection of risk factors that can, without detection and intervention, have deleterious effects on the physical health of patients with SSD [ 10 ].

Several international clinical guidelines have recommended how physical health screening for patients with SSD should be conducted [ 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. According to guidelines persons with SSD who have been prescribed antipsychotic medication should have annual health checks focusing on full blood count, lipids, plasma glucose, prolactin, blood pressure, urea, electrolytes, liver function tests, weight, waist circumference measurement and electrocardiogram examination (ECG) [ 16 ]. Being aware of patients’ lifestyle habits, including smoking and use of other substances [ 10 , 13 , 15 ] is important for directing appropriate behavioral interventions to promote healthy lifestyles. In addition, a variety of screening instruments have been developed to assess physical health among people with SSD. Lamontagne-Godwin et al. [ 17 ] identified in their systematic review 44 intervention studies aiming to increase access to or uptake of physical health screening. Examples of monitoring tools in the included studies were Physical Health Check (PHC) [ 18 ]; physical health monitoring sheet [ 19 ]; systematic computerized cardiovascular health screening [ 20 ]; the Metabolic Syndrome Screening Tool (MSST) [ 21 ]; quality improvement (QI) [ 22 ] to increase rates of metabolic syndrome screening and the Health Improvement Profile (HIP), which is a comprehensive nurse-led profiling tool that assesses physical health risks, identifies unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and provides associated recommended actions for health promotion [ 23 ]. Despite the abundance of available instruments, physical health screening is still poorly implemented in clinical mental health services [ 24 , 25 ].

To better understand this rationale for poor physical health screening, a quantitative study in Uganda [ 26 ] showed, that more than 75% of 28 nurses had a positive attitude towards metabolic screening and associated interventions. The same study reported that more than 50% of nurses were confident in providing physical activity and smoking cessation advice and nutritional counseling. However, 57% stated that their heavy workload prevented them from doing health screening. Voort et al. [ 27 ] reported in their qualitative study in Netherlands, that most nurses perceived physical health screening to be an important part of their professional role, but identified a discrepancy between their perceptions and actual clinical practice. Happell et al.’s qualitative study [ 28 ] reported in Australia that although nurses recognize their responsibility with respect to the physical health of patients with severe mental illness, they experienced factors such as staff shortages and lack of knowledge that prevented them from conducting screening properly. Further, Mwebe [ 29 ] reported in his UK study that nurses shared a clear commitment regarding their role in physical health screening in mental health care settings. Four themes emerged as follows: features of current practice and physical health monitoring; perceived barriers to physical health monitoring; education and training needs; and strategies to improve physical health monitoring. In the UK, Butler et al.’s qualitative study [ 30 ] revealed that patients varied in their awareness of the association between mental and physical health, but were engaged in physical health screening.

Moreover, Bressington et al. [ 31 ] revealed in their qualitative study, that nurses working in Hong Kong psychiatric care settings found the HIP (the Health Improvement Profile) to be comprehensive and perceived positive changes in their patients’ wellbeing, for example, by increasing motivation for patients to improve their health. HIP was developed to increase patient engagement in screening their physical health in collaboration with a nurse [ 32 ]. Earlier studies in the UK [ 33 ], Hong Kong [ 34 ], and Thailand [ 35 ] have reported patient acceptability and clinical utility of the HIP in identifying health risks where interventions are needed. These findings show that HIP may be feasible in engaging patients in discussions about physical health and in identifying areas of health risk [ 34 , 35 ]. Although Hardy et al. [ 33 ] found support for the usability of the HIP in clinical practice in a study in the UK, a subsequent RCT study conducted in the UK revealed that nurses found the use of the HIP unfeasible in a clinical setting due to its length [ 36 ]. In contrast, nurses in Hong Kong [ 31 ] found the HIP to be acceptable, feasible, and potentially useful in clinical practice. In Finland, our validation study of the Finnish Health Improvement Profile (HIP-F) supported this finding by detecting 399 areas of health and health behavior risk in a sample of 47 patients [ 37 ].